Abstract

Indirect maternal deaths outnumber direct deaths due to obstetric causes in many high-income countries, and there has been a significant increase in the proportion of maternal deaths due to indirect medical causes in low- to middle-income countries. This review presents a detailed analysis of indirect maternal deaths in the UK and a perspective on the causes and trends in indirect maternal deaths and issues related to care in low- to middle-income countries. There has been no significant decrease in the rate of indirect maternal deaths in the UK since 2003. In 2011–2013, 68% of all maternal deaths were due to indirect causes, and cardiac disease was the single largest cause. The major issues identified in care of women who died from an indirect cause was a lack of clarity about which medical professional should take responsibility for care and overall management. Under-reporting and misclassification result in underestimation of the rate of indirect maternal deaths in low- to middle-income countries. Causes of indirect death include a range of communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases and nutritional disorders. There has been evidence of a shift in incidence from direct to indirect maternal deaths in many low- to middle-income countries due to an increase in non-communicable diseases among women in the reproductive age. The gaps in care identified include poor access to health services, lack of healthcare providers, delay in diagnosis or misdiagnosis and inadequate follow-up during the postnatal period. Irrespective of the significant gains made in reducing maternal mortality in many countries worldwide, there is evidence of a steady increase in the rate of indirect deaths due to pre-existing medical conditions. This heightens the need for research to generate evidence about the risk factors, management and outcomes of specific medical comorbidities during pregnancy in order to provide appropriate evidence-based multidisciplinary care across the entire pathway: pre-pregnancy, during pregnancy and delivery, and postpartum.

Keywords: Indirect maternal death, medical co-morbidities, pregnancy

Introduction

An indirect maternal death is defined as “maternal death resulting from previous existing disease or disease that developed during pregnancy and which was not due to direct obstetric causes, but which was aggravated by physiologic effects of pregnancy.”1 In 2013, there were a reported 33,128 indirect maternal deaths globally.2 A World Health Organization (WHO) analysis of the causes of maternal death estimated that more than a quarter (28%) of the deaths between 2003 and 2009 were due to indirect causes.3 In high-income countries, indirect causes are widely recognised as contributing to a high proportion of maternal deaths;4–6 however, there has also been a significant increase in the proportion of deaths due to medical comorbidities other than human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) globally between 1990 and 2013.2 Worldwide, of the maternal deaths occurring within 42 days after the end of pregnancy, 15% are estimated to be due to pre-existing medical conditions, making these the second most important underlying cause of maternal death after haemorrhage (27%).3 In addition, a significant proportion of deaths attributable to pre-existing medical conditions occur between six weeks and one year after the end of pregnancy,7 yet these deaths are not recognised within most current estimates of disease burden.

The pregnancy care pathway for women with pre-existing medical and mental health conditions is complex, as a large number of interlinked medical and obstetric factors could aggravate the risk of complications and death in these women. Considering the increase in indirect maternal deaths globally, and the already significant number of deaths attributable to pre-existing medical problems in high-income countries, it is important to understand the incidence, risk factors and management of complications arising from medical and mental health comorbidities in order to prevent indirect maternal deaths. In this review, we discuss the lessons learned from the confidential enquiries into indirect maternal deaths in the UK and present a perspective on the causes and trends in indirect maternal deaths and issues related to care in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs).

Indirect maternal deaths in the UK

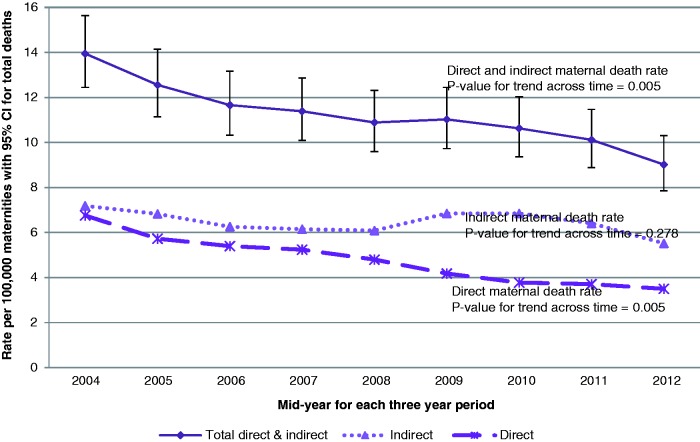

Detailed national surveillance and in-depth review of maternal deaths in the UK undertaken through the confidential enquiry into maternal deaths provide invaluable information about the causes and impact of direct obstetric and indirect medical morbidities on maternal mortality.8 Over the period between 2003–2005 and 2011–2013, maternal deaths in the UK decreased by 35% (95% confidence interval (CI) 23%–46% decrease; p = 0.005 for trend over time), but this was primarily driven by a decrease in direct deaths4 as shown in Figure 1. In contrast, there was no significant decrease in the rate of indirect maternal deaths (classified using ICD-MM) over the same time period (rate ratio (RR) 0.77, 95% CI 0.60–1.00; p = 0.278 for trend over time).4

Figure 1.

Trends in maternal mortality in the UK, 2003–2013 (three-year rolling rates). Direct and Indirect deaths classified using ICD-MM9; Data sources: CMACE, MBRRACE-UK.

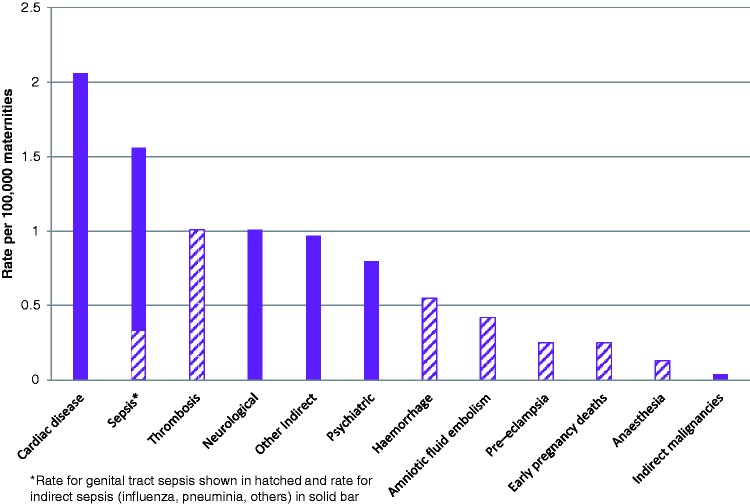

In 2011–2013, more than two-thirds (68%) of UK maternal deaths were due to indirect causes. Cardiac disease was the single largest cause of maternal death, followed by sepsis due to all causes including influenza and pneumonia (noting a relatively minor contribution from genital tract sepsis), neurological causes (including epilepsy) and other indirect deaths (Figure 2).4

Figure 2.

Maternal mortality by cause in the UK, 2011–2013. Solid bars indicate indirect causes of death, hatched bars show direct causes of death; Source: MBRRACE-UK.

After detailed assessment of care received by women with medical conditions who died within 42 days of end of pregnancy,10 a common theme identified was postpartum deterioration which often coincided with lack of clarity about which medical professional (general practitioner, obstetrician, physician) should take responsibility for care, alongside misdiagnosis, as illustrated in the following vignette:10

A multiparous woman with a previous uncomplicated pregnancy died postnatally from systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The diagnosis of lupus nephritis was missed despite clear pointers during her antenatal care. Heavy proteinuria was repeatedly and wrongly attributed to urinary tract infection, despite coincident severe anaemia not responding to oral iron and profound hypoalbuminaemia. Once the diagnosis of SLE was made postpartum, treatment was appropriate, but despite this she deteriorated rapidly and died. (MBRRACE-UK, 201410)

As highlighted recently,11 data on maternal deaths are often collected only up to 42 days after the end of pregnancy, as it is assumed that any sequelae of pregnancy management will occur within this time. However, the adverse effects of medical and mental health comorbidities persist beyond 42 days of the end of pregnancy, and many more pregnant women with pre-existing conditions (such as cardiovascular diseases and mental health problems) die in the period from 42 days up to one year after the end of pregnancy. Between 2009 and 2013, a total of 553 women died in the UK between 42 days and one year after end of pregnancy, almost twice as many as died during and up to 42 days after pregnancy, and pre-existing morbidities accounted for more than 75% of these deaths.4

An obese, hypertensive woman who had pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes had multiple attendances to the Emergency Department with chest or epigastric pain during the months following her delivery. Her ECGs were abnormal on every occasion and two chest X-rays reported cardiomegaly. She was diagnosed variably with gastritis, musculoskeletal pain and gallstones. An abnormal echocardiogram prompted a cardiology referral but no investigations for coronary ischaemia were undertaken. She died suddenly at home from her hypertensive heart disease one week after her most recent cardiology review. (MBRRACE-UK, 20154)

The UK’s maternity population has been undergoing changes, with women giving birth at an older age,12 along with a rise in maternal obesity13; factors known to be associated with increased rates of associated medical problems such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and malignancy. Studies have shown that pre-existing medical problems are associated with increased odds of maternal death in the UK.14,15 At a population level, pre-existing medical problems accounted for 66% of the increased risk of death among pregnant women. Importantly, an investigation of the factors associated with maternal death from direct pregnancy complications in the UK showed that pre-existing medical problems were also important factors associated with deaths due to direct obstetric causes, with almost 50% of the population attributable risk being associated with the presence of medical co-morbidities.14 Specific medical conditions including asthma, autoimmune diseases, inflammatory/atopic disorders, mental health problems, essential hypertension, haematological disorders, musculoskeletal disorders and infections have been found to be associated with a higher risk of dying from eclampsia, pulmonary embolism, severe sepsis, amniotic fluid embolism or peripartum haemorrhage.14

Indirect maternal deaths in LMICs

In LMICs where measurement of maternal death is often less well established, under-reporting of maternal death and misclassification of indirect deaths are important issues. Deaths due to medical comorbidities aggravated by the physiological effects of pregnancy are under-reported due to poor diagnosis of medical conditions,16 and inability to relate them to maternal deaths without an autopsy17 and/or in-depth review resulting in potential misclassification. A comprehensive examination of the causes of 9043 maternal deaths in Mexico between 2006 and 2013 using a new system, Búsqueda intencionada y reclasificación de muertes maternas (BIRMM), reclassified 1214 (13%) of the deaths which were originally categorised as not related to pregnancy as maternal deaths and 21% of these were indirect deaths. The new system reclassified a further 10% of direct deaths as indirect, leading to an overall 6.8% increase in maternal deaths categorised as indirect.18

Despite these problems in measurement, a comparison of the WHO analysis of the causes of maternal deaths between two time periods, 1990–2002 and 2003–2009 showed that the proportion of deaths due to indirect causes has increased substantially in LMICs, the most notable increase being in Latin America and the Caribbean (Table 1). A recent systematic review suggested that 28% of maternal deaths in LMICs in 2003–2009 were due to indirect causes compared with 27% due to haemorrhage and 14% due to hypertensive disorders.3

Table 1.

Changes in the proportion of maternal deaths due to indirect causes between 1990 and 2009.

| Proportion of maternal deaths due to indirect causes (including HIV) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Region | 1990–20021,9 | 2003–20093 |

| High-income countries | 14.4% | 24.7% |

| Africa | 26.6% | Northern Africa 18% Sub-Saharan Africa 28.6% |

| Asia | 12.8% | Eastern Asia 24.9% Southern Asia 29.3% South-east Asia 16.8% Western Asia 23.4% |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 4% | 18.5% |

In contrast to high-income countries where the causes of indirect deaths are mainly non-communicable diseases, in LMICs, the causes include a range of communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases and nutritional disorders. Inclusion and exclusion of conditions that are aggravated by pregnancy have an effect on the estimated rate of indirect maternal deaths; maternal suicides, for example, are still excluded in some estimates. At present, the most common medical conditions known to be associated with indirect maternal mortality in LMICs are HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, iron deficiency anaemia, diabetes mellitus, respiratory diseases and cardiovascular conditions.16,17

AIDS-related maternal death contributes to a substantial proportion of indirect deaths in Sub-Saharan Africa. Worldwide in 2015, 4700 maternal deaths were estimated to be AIDS-related and of these 4000 were in Sub-Saharan Africa.7 Estimates of change in maternal death between 1990 and 2015 showed that in countries where the impact of the HIV epidemic was highest (Malawi, Zimbabwe and South Africa), little or no progress had been made in reducing maternal death.7 HIV infection increases the risk of pregnancy complications directly and indirectly through tuberculosis, anaemia and other secondary infections. Confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in South Africa found that non-pregnancy-related infections such as tuberculosis, pneumonia and other opportunistic infections, in conjunction with HIV, were the most frequent causes of maternal death, contributing 41% of all maternal deaths between 2008 and 2010 and 35% of the deaths in 2011–2013.20 The enquiry also showed that 43% of the women who died had moderate to severe anaemia (haemoglobin concentration <10 g/dl).20 The indirect maternal deaths were attributed to a multitude of health system factors including timely access to appropriate care, availability of drugs, availability and competence of health providers and multidisciplinary care.21

Outcomes in pregnant women with anaemia who develop haemorrhage and sepsis are known to be worse than in women who do not have anaemia. Moderate to severe iron deficiency anaemia during pregnancy has been shown to be associated with increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage22,23 and cardiac failure during pregnancy and delivery.24 An estimated 43% of pregnant women suffer from anaemia in LMICs,25 but it is much higher in certain countries, such as India, where studies report a prevalence as high as 70%–80%.26 Anaemia is identified as the second most frequent cause of maternal death in India, with postpartum haemorrhage reported to be the leading cause,27 and a study in a tertiary hospital in India estimated a prevalence of 9.4% for cardiac failure among pregnant women with severe anaemia.24

In addition to measuring the incidence of direct deaths due to specific obstetric causes and HIV-related indirect deaths, it is important to examine the incidence of other specific important causes of indirect maternal deaths. Surveillance of conditions related to maternal death in the Indian state of Assam undertaken through the Indian Obstetric Surveillance System – Assam (IndOSS-Assam) in two tertiary medical colleges estimated an incidence of 4 per 1000 deliveries for anaemic heart failure, compared with 20 per 1000 for eclampsia and 14 per 1000 for postpartum haemorrhage, but the case fatality rate for anaemic heart failure was 40% compared with fatality rates of 12% and 9% for eclampsia and postpartum haemorrhage, respectively.22

The proportion of maternal deaths due to pre-existing medical conditions in 2003–2009 was estimated to be 15% (95% uncertainty interval 9%–23%) in LMICs compared to 20% (95% uncertainty interval 16%–29%) in high-income countries.3 The prevalence of obesity, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and malignancy in the general population has been increasing in many LMICs,28–30 thereby predisposing women in the reproductive age group to a higher risk of medical comorbidities which in turn could lead to an increase in indirect maternal deaths. Effects of this epidemiological transition are already evident in Mexico where the rate of indirect maternal death has remained unchanged during a period of eight years (13.3 per 100,000 live births in 2013 compared with 12.2 per 100,000 live births in 2006) in contrast to a significant decline in direct maternal deaths.18 While China has made rapid progress in reducing maternal deaths, a study reported a doubling of indirect maternal deaths in the large metropolitan Wuhan city within a decade from 15 per 100,000 live births in 2001 to 37 per 100,000 live births in 2012; cardiac disease was the leading cause.31 Similarly, maternal mortality has decreased in Sri Lanka, but the proportion of deaths due to indirect causes has increased steadily from 1930 to 2000.32

The ‘obstetric transition’ model developed by Souza and colleagues33–35 predicts that with socioeconomic development, improvements in healthcare and increase in age of the maternity population, the causes of maternal death in LMICs will gradually shift from direct obstetric to indirect causes with an increase in indirect deaths due to non-communicable diseases. This shift in pattern will have implications on pregnancy care, requiring a shift from obstetric-focused to coordinated multidisciplinary care. Confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the Indian state of Kerala identified cardiac and hepatic diseases as the leading causes of indirect deaths.36 It was noted that lack of close supervision and multidisciplinary care, delay in diagnosis, inadequate management of the medical condition during pregnancy and a lack of adequate follow-up during the postnatal period (as illustrated in the vignette below) were important factors associated with maternal deaths due to indirect causes.37

A 23 year old woman, a known case of ASD Eisenmenger Syndrome, conceived after four months of marriage, and underwent medical termination of pregnancy. She became pregnant one year later and decided to continue her pregnancy … She was on Sildenafil and Warfarin which were stopped at 14 weeks. She was symptomatic from first trimester and complained of exertional dyspnoea and palpitation[s]. Details about her further antenatal follow up were not available except a note that she had no cardiac symptoms. She delivered vaginally by outlet forceps after induction with prostaglandin, had no problems in the immediate postpartum period and was discharged after starting on Warfarin. She was readmitted with dyspnoea and cough twenty days after discharge and was noted to be in severe cardiac failure. She gave a history of low grade fever for two days. After admission she was started on antibiotics while diuretics and Warfarin continued. She had a sudden cardiorespiratory arrest at night from which she could not be revived. (Kerala confidential inquiries into maternal death 2006–0937)

The above case also highlights the complex interlinked medical and obstetric complications that may arise in women with pre-existing medical problems which can only be managed through multidisciplinary care across the entire pathway, pre-pregnancy, during pregnancy and delivery, and postpartum.

Discussion

Irrespective of the significant gains made in reducing maternal mortality in many countries worldwide, there is evidence of either no change or a steady increase in the rate of indirect maternal deaths due to pre-existing medical and mental health conditions. Due to under-reporting and misclassification of indirect maternal deaths, it is likely that the actual number of indirect maternal deaths in LMICs is considerably higher than the present estimates. Despite this, from systematic reviews of the causes of maternal deaths undertaken by the WHO, it is evident that the proportion of maternal deaths due to indirect causes has been increasing and is now an important cause of all maternal deaths in LMICs and high-income countries.

The causes of indirect maternal deaths vary across countries. Cardiac conditions and other non-communicable diseases are the major causes of indirect deaths in the UK and other high-income countries, HIV infection the primary cause in Sub-Saharan Africa, and iron deficiency anaemia an important cause in Southern Asia.

Reporting and identification of indirect maternal deaths in LMICs is important to first understand the risk factors, management and outcomes of medical and mental health comorbidities during pregnancy, and then, develop interventions through a coordinated and multidisciplinary approach. The common gaps in care of women who died from an indirect cause in the UK and LMICs, whether from medical or mental health conditions are: delays in diagnosis or misdiagnosis and/or inappropriate or inadequate management during and after pregnancy. Both deficiencies in management are inextricably linked to a need for coordinated, multidisciplinary care.

Due to an understandable focus on direct obstetric causes, interventions to reduce maternal deaths in LMICs are concentrated on improving obstetric care for pregnant women through promotion of delivery by skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care. Yet, these strategies have been shown to have no significant effect on reducing the substantial burden of indirect maternal deaths.17 Lessons from the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths from the UK,4,10 Kerala in India,37 South Africa21 and studies from other countries7,18,31,32 suggest the need for policy actions to ensure that health services for pregnant women with medical and mental health conditions are designed to provide appropriate evidence-based multidisciplinary care across the entire pathway; pre-pregnancy, during pregnancy and delivery, and postpartum. In recognition of the potential risks of pregnancy associated with pre-existing conditions, women should be informed about the risks and receive pre-pregnancy counselling from those with expertise in their medical condition and pregnancy.4,10

It should be acknowledged that many women die from medical and mental health conditions between six weeks and one year after the end of pregnancy, and these women are not counted as maternal deaths in many countries. Improvements in healthcare during pregnancy, delivery and the immediate postpartum period are likely to increase the proportion of deaths resulting from late sequelae of obstetric and medical complications, thereby increasing the impact of these late direct and indirect deaths.7 The UK confidential enquiries into maternal deaths showed that more than three-quarters of the late deaths were due to indirect medical causes.4 Therefore, there is a need for tailored follow-up of women with medical and mental health comorbidities postnatally, together with education for healthcare professionals, women, their partners and family members about the possible risks and complications that many still develop late in the postnatal period.

Worldwide, the majority of the research and resources in maternal health is focused on reducing mortality and morbidity due to direct obstetric causes. However, the rising trends in rates of indirect deaths show that an ‘obstetric transition’ is imminent in LMICs where there is a compelling need to conduct surveillance to measure the trends in the incidence of indirect maternal mortality and morbidity due to specific medical causes. Epidemiological studies alongside confidential enquiries and surveillance are needed to generate evidence about the risk factors, management and outcomes of specific medical comorbidities during pregnancy in order to inform pregnancy care guidance in women with pre-existing medical problems. Without adequate and timely evidence, allocation of resources and personnel, and training in medical problems in pregnancy, other actions to contain and reduce indirect maternal deaths will not be forthcoming or effective.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: MK leads the MBRRACE-UK confidential enquiry into maternal deaths. CNP is a central physician assessor for MBRRACE-UK.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Guarantor

MK

Contributorship

MN developed the concept, conducted the literature search and wrote the first draft of the paper. CNP contributed to developing the concept and edited the paper. MK developed the concept and contributed to drafting the paper.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: ICD-MM, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384: 980–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health 2014; 2: e323–e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight M, Tuffnell D, Kenyon S, et al. On behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care – surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2011–2013 and lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2009–2013, Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin M-P, Kildea S. Maternal mortality and psychiatric morbidity in the perinatal period: challenges and opportunities for prevention in the Australian setting. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuitemaker N, van Roosmalen J, Dekker G, et al. Confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in The Netherlands 1983–1992. Eur J Obstetr Gynecol Reprod Biol 1998; 79: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO, Unicef, UNFPA, et al. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurinczuk JJ, Draper ES, Field DJ, et al. Experiences with maternal and perinatal death reviews in the UK—the MBRRACE-UK programme. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol 2014; 121: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: ICD-MM, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care – lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2009–12. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2014.

- 11.Sliwa K, Anthony J. Late maternal deaths: a neglected responsibility. Lancet 2016; 387: 2072–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office for National Statistics. Live births in England and Wales by characteristics of mother, London: Office for National Statistics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heslehurst N, Ells L, Simpson H, et al. Trends in maternal obesity incidence rates, demographic predictors, and health inequalities in 36 821 women over a 15-year period. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol 2007; 114: 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair M, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P, et al. Factors associated with maternal death from direct pregnancy complications: a UK national case–control study. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol 2015; 122: 653–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair M, Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ. Risk factors and newborn outcomes associated with maternal deaths in the UK from 2009 to 2013: a national case–control study. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol 2016; 123: 1654–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Group LMSSs. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006; 368: 1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cross S, Bell JS, Graham WJ. What you count is what you target: the implications of maternal death classification for tracking progress towards reducing maternal mortality in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88: 147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogan MC, Saavedra-Avendano B, Darney BG, et al. Reclassifying causes of obstetric death in Mexico: a repeated cross-sectional study. Bull World Health Organ 2016; 94: 362–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006; 367: 1066–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths. Saving mothers 2011–2013: sixth report on the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa, short report. Department of Health; available at: http://www.kznhealth.gov.za/mcwh/Maternal/Saving-Mothers-2011-2013-short-report.pdf.

- 21.Moodley J, Pattinson RC, Fawcus S, et al. The confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in South Africa: a case study. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol 2014; 121: 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nair M, Choudhury MK, Choudhury SS, et al. The association between maternal anaemia and pregnancy outcomes: a cohort study in Assam, India. BMJ Global Health 2016; 1: e000026–e000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kavle JA, Stoltzfus RJ, Witter F, et al. Association between anaemia during pregnancy and blood loss at and after delivery among women with vaginal births in Pemba Island, Zanzibar, Tanzania. J Health Popul Nutr 2008; 26: 232–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohilla M, Raveendran A, Dhaliwal L, et al. Severe anaemia in pregnancy: a tertiary hospital experience from northern India. J Obstetr Gynaecol 2010; 30: 694–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman MM, Abe SK, Rahman MS, et al. Maternal anemia and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2016; 103: 495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toteja GS, Singh P, Dhillon BS, et al. Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women and adolescent girls in 16 districts of India. Food Nutr Bull 2006; 27: 311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sri BS and Khanna R. Dead women talking: a civil society report on maternal deaths in India. Commonhealth and Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, 2014; available at: http://www.commonhealth.in/Dead%20Women%20Talking%20full%20report%20final.pdf.

- 28.Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: s9–s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. Global prevalence of diabetes estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ôunpuu S, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation 2001; 104: 2746–2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang S, Zhang B, Zhao J, et al. Progress on the maternal mortality ratio reduction in Wuhan, China in 2001?2012. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e89510–e89510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernando D, Jayatilleka A, Karunaratna V. Pregnancy—reducing maternal deaths and disability in Sri Lanka: national strategies. Br Med Bull 2003; 67: 85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaves SC, Cecatti JG, Carroli G, et al. Obstetric transition in the World Health Organization multicountry survey on maternal and newborn health: exploring pathways for maternal mortality reduction. Rev Panam Salud Pública 2015; 37: 203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Souza JP. Maternal mortality and development: the obstetric transition in Brazil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2013; 35: 533–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souza J, Tunçalp Ö, Vogel J, et al. Obstetric transition: the pathway towards ending preventable maternal deaths. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol 2014; 121: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paily V, Ambujam K, Rajasekharan Nair V, et al. Confidential review of maternal deaths in Kerala: a country case study. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol 2014; 121: 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paily V, Ambujam K, Thomas B. Why mothers die: Kerala 2006–2009 observations, recommendations, Thrissur: Kerala Federation of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 2012. [Google Scholar]