Abstract

Purpose of Review:

To hear from living kidney donors and recipients about what they perceive are the barriers to living donor kidney transplantation, and how patients can develop and lead innovative solutions to increase the rate and enhance the experiences of living donor kidney transplantation in Ontario.

Sources of Information:

A one-day patient-led workshop on March 10th, 2016 in Toronto, Ontario.

Methods:

Participants who were previously engaged in priority-setting exercises were invited to the meeting by patient lead, Sue McKenzie. This included primarily past kidney donors, kidney transplant recipients, as well as researchers, and representatives from renal and transplant health care organizations across Ontario.

Key Findings:

Four main barriers were identified: lack of education for patients and families, lack of public awareness about living donor kidney transplantation, financial costs incurred by donors, and health care system-level inefficiencies. Several novel solutions were proposed, including the development of a peer network to support and educate patients and families with kidney failure to pursue living donor kidney transplantation; consistent reimbursement policies to cover donors’ out-of-pocket expenses; and partnering with the paramedical and insurance industry to improve the efficiency of the donor and recipient evaluation process.

Limitations:

While there was a diversity of experience in the room from both donors and recipients, it does not provide a complete picture of the living kidney donation process for all Ontario donors and recipients. The discussion was provincially focused, and as such, some of the solutions suggested may already be in practice or unfeasible in other provinces.

Implications:

The creation of a patient-led provincial council was suggested as an important next step to advance the development and implementation of solutions to overcome patient-identified barriers to living donor kidney transplantation.

Keywords: living kidney donation, Ontario, patient-oriented research, workshop

Abrégé

Objectifs de la revue:

Obtenir l’avis des donneurs de rein et des receveurs d’une greffe ontariens sur ce qu’ils considèrent comme des obstacles aux transplantations rénales provenant d’un donneur vivant, et sur la manière dont les patients pourraient élaborer et mener à bien des solutions innovantes pour accroître le nombre de greffes et améliorer l’expérience d’un donneur vivant à la suite d’une transplantation rénale.

Sources:

Les données ont été recueillies lors d’un atelier d’une journée dirigé par les patients, qui s’est tenu le 10 mars 2016 à Toronto (Ontario).

Méthodologie:

Les participants, qui s’étaient préalablement livrés à des exercices visant à définir des priorités, ont été invités à prendre part à l’atelier présidé par Sue McKenzie, une patiente. Le groupe de participants était constitué en premier lieu de donneurs de reins et de receveurs d’une greffe, mais également de chercheurs et de représentants de divers organismes en soins de santé rénale et en transplantation de partout en Ontario.

Principales conclusions:

Quatre principaux obstacles ont été identifiés : le manque d’information destinée aux patients et à leurs familles, le manque de sensibilisation auprès du public relativement aux donneurs vivants, les frais financiers encourus par les donneurs et, de façon globale, les inefficacités en matière de soins dans le système de santé. Plusieurs solutions ont été proposées lors de l’atelier, notamment l’élaboration d’un réseau de pairs visant à supporter les patients souffrant d’insuffisance rénale ainsi que leur famille et à les informer au sujet de la transplantation avec un donneur vivant. On a également proposé l’adoption de politiques de remboursement pour couvrir les frais encourus par les donneurs et l’établissement de partenariats entre le paramédical et les compagnies d’assurances afin d’améliorer l’efficacité du processus d’évaluation donneur-receveur.

Limites:

Malgré la diversité des expériences vécues par les donneurs et les receveurs présents dans la salle, l’ensemble des réponses ne fournit pas un portrait complet du processus de don de rein vivant qui soit représentatif de tous les donneurs et receveurs de l’Ontario. La discussion portait sur des obstacles et des solutions spécifiques à la situation en Ontario. Par conséquent, il est possible que certaines des solutions apportées soient déjà en pratique ou au contraire, s’avèrent impossibles dans d’autres provinces.

Conclusions:

La création d’un conseil provincial, mené par un patient ou une patiente, a été proposée comme étant la prochaine étape cruciale pour faire progresser la conception et la mise en œuvre de solutions concrètes permettant de surmonter les obstacles à la transplantation rénale avec donneur vivant qu’ont identifiés les patients.

What was known before

Living kidney transplantation is the optimal treatment for many patients with end-stage kidney disease yet Canada’s rate of living kidney donation is 35% lower than other Western countries.

What this adds

This patient-centered meeting provided insights from both donors and recipients into the barriers faced during the transplantation process and produced several novel, patient-centered solutions.

Introduction

The health of millions of people worldwide who experience kidney failure could be improved if more kidneys were available for transplant. Transplantation offers patients renewed freedom and productivity, and an extended and improved quality of life, all at a fraction of the cost of dialysis.1-3 The Canadian health care system saves approximately $20 million in averted dialysis costs over a 5-year period for every 100 kidney transplants.3,4 Unfortunately, many patients who would benefit from a kidney transplant do not receive one. The number of people in need of a transplant continues to rise, and there are too few kidneys available from deceased donors to meet the demand.5,6 The alternative, a transplanted kidney gifted from a living donor, offers many advantages that include a longer duration of patient and graft survival, shorter wait times to receive a kidney, and substantial health care savings from averted years on dialysis. Across the globe, countries are urged to meet the demand for transplantable kidneys by increasing their rates of living kidney donation. In Canada however, the donation rate has stagnated at approximately 14.5 per million population since 2006,6,7 which is 35% lower than several other Western nations.8,9

Methods

The Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD) is a pan-Canadian patient-oriented research network that aims to improve the lives of those living with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Can-SOLVE CKD held a conference in 2015 where kidney patients, practitioners, and researchers collectively ranked the need to improve living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) as the top research priority in Canadian nephrology. This call to action spurred a subsequent patient-led workshop, facilitated by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation Research Program (ICES-KDT) which was held on March 10, 2016 in Toronto, Canada, coinciding with World Kidney Day. Workshop goals were to (1) identify barriers to living kidney donation and transplantation based on the personal experiences of patients, and (2) discuss potential solutions to these barriers. Participants included primarily past kidney donors, kidney transplant recipients, as well as family members (see Figures 1-3 for patient participant demographics). The meetings’ patient organizer, Sue McKenzie, invited those who were previously engaged in priority-setting exercises as well as other donors and recipients she was connected with from her work at the Kidney Foundation of Canada. Researchers and representatives from renal and transplant health care organizations across Ontario were also invited to attend. The synthesis provided in this report was based on detailed notes taken during the meeting by JH and MM, data extracted from table surveys and discussions followed by a thematic analysis by LG to present the top barriers to living kidney transplantation, and the general consensus on patient-centered solutions. The manuscript was shared with all those who attended, and corresponding feedback was incorporated.

Figure 1.

Patient participation.

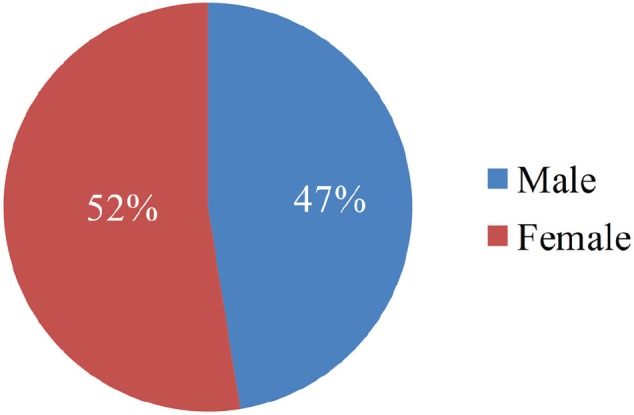

Figure 2.

Patient gender distribution.

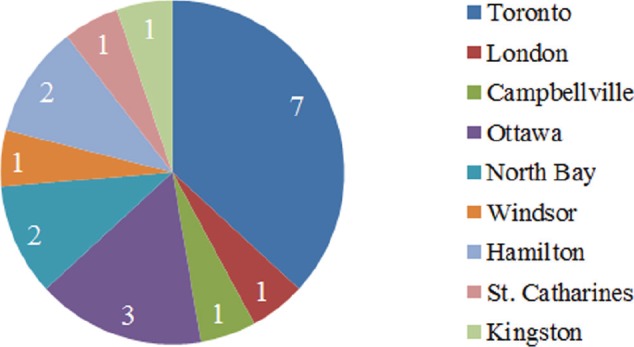

Figure 3.

Patient geographical representation.

Results

Recipient and donor identified barriers to LDKT.

In our discussion on the barriers to LDKT, 4 key themes emerged: (1) lack of education for patients and families, (2) lack of public awareness on LDKT, (3) financial cost to donors, and (4) health care system–level barriers.

Lack of Education for Patients and Families

Patient education

Participants consistently identified a need for targeted education on LDKT in earlier stages of kidney disease, as well as guidance and support for those who are in need of finding a donor. Many patients with end-stage kidney disease do not learn early enough that living kidney donation is an optimal choice for renal replacement therapy. In addition, some participants cited difficultly in approaching family and friends about the need for a donated kidney and did not know where to turn for help.

Inconsistent patient education within a siloed system

Currently, there are multiple organizations that provide transplant-related education. There are opportunities to improve the coordination of high-quality education and information to patients and their families. Many patients indicated it was difficult for them to obtain direct access to clear, timely, and consistent information about LDKT. There are 26 CKD programs in the province and 7 hospitals with autonomous adult transplant programs. Provincial health care organizations include the Ontario Renal Network, the Trillium Gift of Life Network (TGLN), and the Ontario Chapter of the Kidney Foundation of Canada; national-level organizations include Canadian Blood Services (CBS) and the Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation of Canada to name only a few. With an uncoordinated approach to patient and family education, the consequence is often inconsistent information, which many patients indicated led to feelings of confusion, hopelessness, and sometimes outright disengagement from the process of exploring transplantation. In addition, with varying sources of information, some patients may misinterpret what they read and unknowingly begin to share incorrect information. This enhances the problem of a siloed and complex system and can lead to the creation of “urban myths” around living kidney donation—deterring potential donors and disadvantaging those who would benefit from a transplant.

Lack of public awareness about LDKT

Although there have been many public awareness efforts in Ontario and Canada about the opportunities for deceased organ donation, there has been almost no activity around raising public awareness of living kidney donation and transplantation. With the growing prevalence of CKD,10 there is a clear need to increase public awareness about this disease and its treatment options. LDKT provides the best possible outcomes for the majority of CKD patients,11-14 and a concerted effort is needed to increase the profile of living donation in the general population. Many patients experience barriers accessing information about kidney disease and transplantation, and these barriers are often replicated outside of the health care system. Some of the barriers facing potential donors include the plethora of resources outlining differing policies and procedures to living donation, uncertainty within various religious and cultural groups regarding the ability to donate, myths15 about donation, and most importantly, profound gaps in knowledge and understanding about the need for and benefits of living kidney donation and transplantation. These barriers can cause confusion, delay, and even dismissal of the donation process altogether.

Financial Barriers to LDKT

The cost to donors

Participants all agreed that the process of kidney donation should be financially neutral for the donor, yet this is not the case for most donors. Nearly all kidney donors (96%) incur out-of-pocket costs as a result of donor evaluation and surgery. These costs can include expenses related to travel, accommodation, lost wages, medications, and child care.16-19 As well, donors who participate in the National Living Kidney Donor Paired Exchange Registry managed by CBS must often travel long distances at short notice.20 For those with little savings or income, the financial risks of donation may act as an insurmountable barrier. The recent development of reimbursement programs such as the TGLN’s Program for Reimbursing Expenses of Living Organ Donors is a positive development; however, the current system still has limitations and cannot yet support the total financial costs incurred by most donor candidates.

Health Care System–Level Barriers to LDKT

Lengthy donor evaluation process

I feel like my life is on hold; if I’d known it would take this long, I never would have signed up for this. (A Canadian who waited a year to donate a kidney)

Although living kidney donor candidate evaluation is a multifaceted process with over 50+ tests required from multiple health care providers,21,22 most participants indicated that the current practice is long and inefficient. With a long evaluation process, there is a greater period over which the intended recipient may become ill, and may no longer be eligible to receive a kidney transplant. Non-directed altruistic donors and donors who participate in kidney paired donation (where the wait is even longer) may opt out of the evaluation process due to frustration.

Navigating a fragmented donor evaluation system

In addition to the current lengthy donor evaluation process, many other factors contribute to the low numbers of living kidney transplants. Our participants identified some gaps in the current system as CKD clinics often have different policies and procedures than their partnering transplant units. There is an opportunity to ensure a collaborative and continuous kidney care continuum with improved patient transitions between renal and transplant programs (see Table 1 for a summary of patient identified barriers to LDKT).

Table 1.

A Summary of Comments Made During Break-Out Group Discussions on Barriers to LDKT.

| Educational barriers | General lack of knowledge about living kidney donation can lead to a “fear” of the unknown. Not all donors and recipients are given the same information—there are regional and provincial inconsistencies. How do you navigate the system? Where do you go if you want to donate? Misconceptions—those receiving a living kidney donation are “jumping the queue ahead of those who are waiting for a deceased organ.” Too many sources of information, sometimes contradictory and very overwhelming—this leads to the creation of “urban myths” and people cannot decipher this from credible information. Lack of information for donors and a gap in long-term follow-up for donors. “Everyone knows about cancer,” but this is not the case with kidney disease. The public understands the need to donate blood, but do not generally know about the importance of living organ (kidney) donation. |

| Financial barriers | Potential loss of income for donors who need to take time off work to go through multiple tests as well as recovery time after surgery. Associated costs with donor testing and surgery can include parking, mileage, child care, accommodation, travel, new diets, vitamins, and so forth. Post-discharge medications can be expensive if the donor does not have benefits. Existing reimbursement programs are inadequate to cover the true costs of donation. |

| System-level barriers | Donor candidate evaluation is too long. Poor/delayed communication between primary care physicians, nephrologists, dialysis staff, and transplant centres, which often leads to poor care. Not enough time to talk to patients about transplantation. Uncoordinated approach provincially and nationally. Lack of consistency—each hospital has a different set of protocols, therefore sharing information across regions is difficult and leads to misinformation. The system is overly bureaucratic, and it is easy to fall through the cracks. Additional barriers for FNIM populations as many, particularly in rural areas, do not have access to primary care. FNIM communities receive federal health care funding, but transplantation care is organized provincially. |

Note. LDKT = living donor kidney transplantation; FNIM = First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

Patient-Identified Solutions to Increase the Rate of LDKT

Improved Education and Public Awareness

Patient education through targeted educational materials

An “educational toolkit” for patients with kidney failure and their families was suggested by participants as an important and simple solution to providing timely and relevant information about living kidney donation. Donor recipients at the meeting identified the “Big Ask” (asking a friend or family member to consider living kidney donation) as an area where formalized resources would be greatly advantageous. Having educational materials that will target both potential LDKT donors and recipients will ensure the right information is being received at the optimal time.

Public education through private sector partnership

The Bell “Let’s Talk” campaign to promote awareness and remove stigma around mental health (letstalk.bell.ca) proved to be a common example among participants as a prime illustration of how partnership with the private sector can bring nationwide awareness and promote dialogue around a particular cause. Many suggested that finding a champion to promote living kidney donation would significantly benefit CKD patients in need of a donated kidney. The group was excited to learn about the efforts of Cindy Cherry and Susan McKenzie, two workshop participants. In their roles with the Kidney Foundation of Canada, they have recently completed a pilot project with the Ontario Hockey League’s London Knights titled “Play it Forward.” This successful pilot program promoted registration for deceased organ donation during eight of the London Knights home play-off games between March 12 and April 14, 2015. The program was made possible through a unique partnership between the Kidney Foundation of Canada, London Health Sciences Multi-organ Transplant Centre, the London Knights, and the Cherry Family. The program increased media and community attention around deceased organ donation and was endorsed by the team who have already agreed to participate again in 2017. The “Play It Forward” campaign is now being promoted across the Canadian Hockey League, and several other teams across Canada will participate in 2017. The enthusiasm around engaging a national champion and the efforts of the “Play It Forward” organizers have set the stage to begin the important work of educating the general public about the critical importance of deceased organ donation. Also discussed was the opportunity to expand the campaign to include a component of living kidney donation.

Patient education and support through peer mentorship

Patient peer mentors have often faced the same challenges and decisions as other patients with kidney failure, and sharing their experiences with one another is viewed as highly valuable.23 The Kidney Foundation of Canada’s Kidney Connect program is an online peer-support program offering patients, families, and friends an opportunity to connect via blogs, groups, and online chats (www.kidneyconnect.ca). Acknowledging the important role this program plays in offering a peer-support opportunity for individuals, there was general consensus among participants that a coordinated in-person peer connection is needed. Having a patient peer mentor available in the waiting rooms of kidney clinics would provide early support to new patients who might not know about LDKT. Well-trained peer mentors can provide invaluable emotional support and practical guidance based on their lived experience.

Increased public awareness through youth education

When youth are engaged and empowered, the benefits to society are plentiful.24 Educating young people was seen as one avenue to greater public awareness as they could become advocates and knowledge ambassadors about LDKT. Inviting youth to be involved in future workshops and research and introducing living donor education through elementary and secondary school curricula was agreed to be a strong way forward. Our young people are innovators and will be the donors and recipients of tomorrow.

Removing Financial Barriers for Donors

Although it was agreed the entire donor evaluation process should be financially neutral, there could be many small changes easily implemented that would make the entire process more manageable and less daunting in the meantime. A clear illustration was provided during our meeting of the disparity experienced by living donor candidates across the province with respect to financial compensation. At one center, candidates were given monthly parking passes to allow easy access to the hospital for testing, and these candidates were also able to avoid out-of-pocket expenses and receipt tracking that many others said they were forced to contend with. There is an opportunity to develop best practices that can be easily implemented across the province (ie, parking passes vs receipt tracking) though continued work is being done to remove the cost for donors altogether.

Removing Health Care System–Level Barriers to LDKT

Donor evaluation

We know the evaluation process to determine suitability for kidney donation and transplantation is often much too long and has real implications, including deteriorating conditions of those waiting for transplantation. Participants agreed on the importance of a high-quality donor evaluation, but believed there are many inefficiencies with the current process that need to be addressed. Two novel ideas were presented by participants and both were tied to developing strategic partnerships with the insurance industry. When individuals are being assessed for life insurance, often a medical exam is required. These screening appointments are conducted at the client’s home, and though comprehensive, often take less than one hour to complete. Leveraging the expertise, methods, and technologies used by the examining paramedical companies would be an ideal way to quickly and accurately evaluate an interested living donor candidate. In addition, participants saw an opportunity to have insurance companies share the option of being further evaluated for living kidney donation with clients should the results of their insurance medical exams identify them as good candidates.

Centralized source of information

Many comments were made throughout the day about the multiple silos of information that exist related to accessing information on LDKT. The creation of a centralized and neutral source of information, similar to an “ombudsperson,” was suggested to address this barrier. Having a place (virtual) or body (person) where current and future living kidney donors and their families can go to get all their questions answered, as well as receive support in navigating the system was suggested by various participants and generated widespread support.

Technology and the sharing economy

Peer-to-peer sharing networks have rapidly created a new global sharing economy worth $26 billion dollars.25 These are networks of individuals from wide geographic areas who are looking to share what they have (be it cars, homes, or personal expertise) with others. Participants believed that leveraging the methods and success of peer-to-peer sharing networks (ie, airbnb) could help increase the number of living donor kidney transplants—by matching those interested in “sharing” a kidney to a patient in need of a transplant. Matchingdonors.com is a US-centric website that currently matches interested donors with patients, but our group would like to see a Canadian specific site developed (see Table 2 for a summary of patient identified solutions to increase the rate of LDKT).

Table 2.

A Summary of Patient-Identified Solutions to Increase the Rate of LDKT Devised During Break-Out Discussions.

| Education for patients and families and public awareness | Modules in elementary and high school as a way to engage youth. Creation of a “Kidney Ombudsperson” to act as a central point of contact for all LDKT-related questions, information, and issues. Create 1-800 or a 53 number that would send callers to a centralized database of information. Corporate champion to sponsor something similar to the “Bell Let’s Talk” mental health awareness campaign. Ministry of Transportation and Service Canada locations could include a question about living organ donation when they ask about deceased donation. Peer Mentoring program where past donors and recipients can provide support and guidance to those seeking more information. An educational toolkit of information on what to expect, FAQs, and resources to navigate “the Big Ask”. |

| Financial | Provide tax receipts for potential donors and accepted donors. Anyone who is making multiple hospital visits should be provided with a monthly parking pass or equivalent. Streamline reimbursement processes. Ultimately remove all financial cost to donors. |

| Systematic barriers | Use paramedical expertise through insurance companies to efficiently do many components of the donor candidate evaluation. A “Kidney Ombudsperson” would be a central point for assistance in the navigating system. Centralized center for all donors and recipients (not through the hospital). Ask those who are not a match for their loved one if they would still consider donating in a kidney paired donation program. The definition and acceptability of public solicitation in centers needs to be standardized. A national registry for deceased and living donors (https://openparliament.ca/bills/42-1/C-223/). |

Note. LDKT = living donor kidney transplantation.

Discussion

Limitations

We acknowledge that while there was a diversity of experience represented at this workshop, we did not capture a complete picture of the living kidney donor transplantation experience in Ontario. Although our discussion was provincially focused, we recognize that other provincial models of care can also provide important solutions to some of the barriers identified in the workshop. It is important to recognize that increased awareness about LDKT may place additional burden on the system if it is not adequately prepared to support an increase in demand. All solutions must be addressed within the context of the entire health care system and various socio-cultural and economic realities of the entire CKD population.

Conclusion

A clear illustration was painted by the participants at this meeting around the need to address barriers to LDKT. Four main areas were identified as obstacles: lack of education for patients and families, lack of public awareness about LDKT, financial costs incurred by donors, and health care system–level inefficiencies. Several novel solutions were suggested, including peer mentorship, education through private sector partnership, youth education, consistent reimbursement policies to cover donors’ out-of-pocket expenses, partnering with the paramedical/insurance industry to hasten the donor and recipient evaluation process, capturing the popular rise in the sharing economy to better connect potential donors with recipients, and the creation of a centralized source for information and support for LDKT in Ontario. The creation of a patient-led provincial council was suggested as an important next step to advance the development and implementation of solutions to overcome identified barriers to LDKT.

Implications

Patient-led provincial council

The creation of an independent group comprising living kidney donors and recipients was widely supported among participants as a meaningful and impactful way to move forward. This council will consist of participants from this meeting as well as others to ensure a patient-led approach to developing and implementing solutions to overcoming barriers to LDKT in Ontario. How this council will partner with existing provincial agencies, CKD, and transplant clinics and will be administratively supported is yet to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Attendees: Patients (patients with kidney failure, kidney donors, or kidney transplant recipients): Allison Knudsen, Cathy Woods, Cindy Cherry, Craig Dunbar, Dale Bouskill, David Brown, Eileen Freedman, Garry Keller, Jason Kroft, Lawrence Geller, Sybil Geller, Lisa Caswell, Mary Beaucage, Michael McCormick, Michelle MacKinnon, Nola Johnson, Stephanie Bouskill, Tracy Arthurs, Susan McKenzie.

Organizations: Amit Garg, Leah Getchell, Jade Hayward, Megan McCallum, Jessica Sontrop, Kyla Naylor, Steven Habbous, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation Research Program; Christina D’Antonio, Jocelyn Pang, the Ontario Renal Network; Christina Parsons, Canadian Blood Services; Laura Todd, Trillium Gift of Live Network; Istvan Mucsi, Division of Nephrology, Multi-organ Transplant Program, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario.

Foremost, this workshop was made possible through the initiative and efforts of Susan McKenzie, a living kidney donor recipient who is passionate about increasing awareness and rates of living kidney donation and transplantation in Canada. CanSolve-CKD has been a leader in patient-oriented research and provided support for the foundational activities that led to this important and insightful meeting.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Ethics approval was not needed as this was not a clinical research study.

Consent for Publication: All authors have reviewed the manuscript and consent to its publication in its current form.

Availability of Data and Materials: Availability of Data and Materials are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AXG is the principal investigator of the Canadian Living Kidney Donor Safety Study, which is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Astellas Pharma Canada, Inc. Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD) is in part funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research and the Kidney Foundation of Canada. SQM is also employed by the Kidney Foundation of Canada, Western Canada.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This workshop was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and participants and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC should be inferred.

References

- 1. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2093-2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klarenbach S, Barnieh L, Gill J. Is living kidney donation the answer to the economic problem of end-stage renal disease? Semin Nephrol. 2009;29:533-538. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Kidney Foundation of Canada. Facing the facts. http://www.kidney.ca/file/Facing-the-Facts-2015-infographic-portrait.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- 4. Klarenbach SW, Tonelli M, Chui B, Manns BJ. Economic evaluation of dialysis therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:644-652. http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nrneph.2014.145. Accessed February 28, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moore DR, Serur D, Rudow DL, Rodrigue JR, Hays R, Cooper M. Living donor kidney transplantation: improving efficiencies in live kidney donor evaluation recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1678-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim SJ, Fenton SS, Kappel J, et al. Organ donation and transplantation in Canada: insights from the Canadian Organ Replacement Register. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2014;1:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian organ replacement register annual report: treatment of end-stage organ failure in Canada, 2004 to 2013. 2014. https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?locale=en&pf=PFC2864&lang=en

- 8. Horvat LD, Shariff SZ, Garg AX. Global trends in the rates of living kidney donation. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1088-1098. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White, et al. The Global diffusion of organ transplantation: trends, drivers and policy implications. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2014. p.4 www.who.int/bulletin/online_first/blt.14.137653.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. Arora P, Vasa P, Brenner D, et al. Prevalence estimates of chronic kidney disease in Canada: results of a nationally representative survey. CMAJ. 2013;185:E417-E423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725-1730. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10580071. Accessed February 28, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rabbat CG, Thorpe KE, Russell JD, Churchill DN. Comparison of mortality risk for dialysis patients and cadaveric first renal transplant recipients in Ontario, Canada. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:917-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ozcan H, Yucel A, Avşar UZ, et al. Kidney transplantation is superior to hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in terms of cognitive function, anxiety, and depression symptoms in chronic kidney disease. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:1348-1351. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0041134515003577. Accessed February 28, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whiting JF, Kiberd B, Kalo Z, Keown P, Roels L, Kjerulf M. Cost-effectiveness of organ donation: evaluating investment into donor action and other donor initiatives. Am J Trans-plant. 2004;4:569-573. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15023149. Accessed February 28, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ilana B, Levine S, Charlton M. Myths about living kidney donation. http://www.lkdn.org/kidneykampaign/Myths_About_Living_Kidney_Donation.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- 16. Klarenbach S, Gill JS, Knoll G, et al. Economic consequences incurred by living kidney donors: a Canadian multi-center prospective study. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:916-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sickand M, Cuerden MS, Klarenbach SW, et al. Reimbursing live organ donors for incurred non-medical expenses: a global perspective on policies and programs. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2825-2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vlaicu S, Klarenbach S, Yang RC, Dempster T, Garg AX. Current Canadian initiatives to reimburse live organ donors for their non-medical expenses. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:481-483. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19039887. Accessed February 28, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clarke KS, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, Yang RC, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network. The direct and indirect economic costs incurred by living kidney donors-a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1952-1960. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16554329. Accessed February 28, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canadian Blood Services. I’m not a match for my kidney, can I still donate? https://www.blood.ca/sites/default/files/english_ldpe_brochure_donor.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- 21. Reese PP, Boudville N, Garg AX. Living kidney donation: outcomes, ethics, and uncertainty. Lancet. 2015;385:2003-2013. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62484-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes. http://kdigo.org/home/guidelines/livingdonor/. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- 23. Thoits PA. Social support as coping assistance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:416-423. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3745593. Accessed February 28, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ho E, Clarke A, Dougherty I. Youth-led social change: topics, engagement types, organizational types, strategies, and impacts. Futures. 2015;67:52-62. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2015.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Byers J, Proserpio D, Zervas G. The rise of the sharing economy: estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. SSRN Electron J. 2013;13:1-36. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2366898. Accessed February 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]