Abstract

Background:

Human factors play an important role in health-care outcomes of heart failure (HF) patients. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trial studies on HF hospitalization may yield positive proofs of the beneficial effect of specific care management strategies.

Purpose:

To investigate how the 8 guiding principles of choice, rest, environment, activity, trust, interpersonal relationships, outlook, and nutrition reduce HF readmissions.

Basic Procedures:

Appropriate keywords were identified related to the (1) independent variable of hospitalization and treatment, (2) the moderating variable of care management principles, (3) the dependent variable of readmission, and (4) the disease of HF to conduct searches in 9 databases. Databases searched included CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ERIC, MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycInfo, Science Direct, and Web of Science. Only prospective studies associated with HF hospitalization and readmissions, published in English, Chinese, Spanish, and German journals between January 1, 1990, and August 31, 2015, were included in the systematic review. In the meta-analysis, data were collected from studies that measured HF readmission for individual patients.

Main Findings:

The results indicate that an intervention involving any human factor principles may nearly double an individual’s probability of not being readmitted. Participants in interventions that incorporated single or combined principles were 1.4 to 6.8 times less likely to be readmitted.

Principal Conclusions:

Interventions with human factor principles reduce readmissions among HF patients. Overall, this review may help reconfigure the design, implementation, and evaluation of clinical practice for reducing HF readmissions in the future.

Keywords: heart failure readmission, care management strategies, moderating effects of human factors in heart health care, risk reduction approach

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a chronic and progressive condition in which the heart muscle is unable to pump enough blood to meet the body’s need for blood and oxygen.1 Placement into class I, II, III, or IV of the New York Heart Association functional classification depends on the severity of patient symptoms and physical activity limitations.1 Heart failure is a leading cause of hospitalization and health-care costs in the United States. Nearly 5.1 million Americans have been diagnosed with HF, and approximately half die within 5 years of diagnosis.2,3 The total costs of HF to the nation, in terms of direct medical costs and lost productivity, are estimated to be US$32 billion annually.2,3 Congestive HF is the most common reason for readmission among Medicare fee-for-service patients,4 and up to 25% of HF patients are readmitted within 30 days.5 An analysis of Medicare claims data from 2007 to 2009 showed that 35% of readmissions within 30 days were for HF.5 Section 3025 of the Affordable Care Act amended the Social Security Act to establish the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which requires the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to decrease reimbursements to hospitals with excessive risk-standardized readmissions.6 This program encourages hospitals to develop interventions to reduce the readmission rates for HF patients. Increasingly, care management practices incorporate human factors that can influence the relationship between therapeutic interventions and patient outcomes. These interventions commonly involve human factors, including components such as education and assessment, rest and relaxation, exercise, interpersonal relationships, outlook, and dietary recommendations.

Research Questions

In a search for the causal mechanisms for enhancing patient care outcomes, this investigation explored how scientific literature has documented the moderating influence of varying care management principles involving human factors on hospital outcomes of HF patients. A systematic review of intervention strategies was conducted, and a broad range of intervention types aimed at reducing HF readmissions was included. The selected intervention components include education and assessment, rest and relaxation, exercise, interpersonal relationships, outlook, and dietary recommendations. The systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to answer the following research questions:

Is there evidence that particular intervention components may modify the care management effects on HF readmission?

Does a single intervention component work more effectively than a combination of intervention components in care management for HF patients?

How can the knowledge gained from the systematic review and meta-analysis be applied in population health management for HF?

Material and Methods

Data Sources and Searches

Appropriate keywords were identified related to (1) the independent variable of hospitalization and treatment, (2) the moderating variable of intervention components, (3) the dependent variable of readmission, and (4) HF. Combinations with 1 keyword from each of the 4 categories (see Table 1) were used to conduct searches in 9 databases: CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ERIC, MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycInfo, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science. Although systematic reviews were not included in the meta-analysis, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was searched in case any similar studies existed.

Table 1.

List of Keywords for Database Searches.

| Variable | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Heart failure | Heart failure |

| Intervention | Medicine, medication, hospital, inpatient, outpatient, health education, behavior modification, motivational interviewing |

| Outcome | Rehospitalization, readmission, health-related quality of life |

| Education/assessment | Internal-external control, choice behavior, responsibility, goal-setting |

| Rest/relaxation | Relaxation, rest, sleep |

| Environment | Built environment, pollution |

| Exercise | Leisure activities, exercise, recreation, sports |

| Religion/spirituality | Trust, belief, higher power, religion, spirituality |

| Interpersonal relationships | Family relations, interpersonal relations, sibling relations, professional-family relations, professional-patient relations, social participation, social capital |

| Outlook | Mindfulness, control, self-efficacy, emotion*, optimism, stress* |

| Dietary | Food habits, meals, food preferences, food security |

Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Quality Assessment

Table 2 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria in regard to population, interventions, outcomes, timing of outcomes, time period, settings, publication language, design, and publication format. Only studies associated with HF hospitalization and readmissions, published in English, Chinese, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish between January 1, 1990, and August 31, 2015, were compiled. Retrospective studies were excluded. Studies that evaluated interventions focused on only pharmaceuticals, surgical procedures, technology, or other therapeutic strategies and that did not incorporate any of the selected human factors were excluded. Each selected study was reviewed by a team of 5 graduate students with training in rating the quality. The detailed characteristics of cited studies are listed in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Studies of Intervention Patients Hospitalized for HF.

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults with heart failure | Children and adolescents |

| Interventions | Interventions that include 1 or more of the components listed | Interventions that do not incorporate 1 or more of the components listed |

| Outcomes | Readmission to hospital | Only a quality of life or functional status outcome with no mention of readmission to hospital |

| Timing of outcome | Outcomes occurring within 24 months of hospitalization | Outcomes occurring more than 24 months after hospitalization |

| Time period | Studies published from January 1, 1990, to August 31, 2015 | Studies published before January 1, 1990, or after August 31, 2015 |

| Settings | Interventions occurring during hospitalization before discharge; interventions occurring in an outpatient setting after discharge from hospital; interventions bridging the transition from inpatient to outpatient care | All other settings, such as discharge from hospital to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center |

| Publication language | English, Chinese, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish | Any other languages |

| Design | Original research, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-RCTs, prospective cohort studies with comparison group | Case reports, case–control studies, retrospective cohort studies |

| Publication format | Peer-reviewed articles in an academic journal | Books, book reviews, continuing education units (CEUs), conference abstracts, dissertations, nonsystematic reviews, systematic reviews, editorials, letters to the editor |

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Studies that focused on HF and other chronic illnesses and reported the number of readmissions for only HF patients were included if they met the inclusion criteria. All studies that reported the number of persons readmitted in each group were included in the meta-analysis. Although a study that only reported the total number of readmissions per group was included in the systematic review, it was not included in the meta-analysis. Additionally, studies in the systematic review could not be included in the meta-analysis if they evaluated multiple intervention groups and a control group rather than only 1 intervention group and 1 control group, or if the study reported numbers for only composite outcomes, such as readmission and death.

In the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Version 2) software,7 a mixed-effects model was used to synthesize effect sizes from independent studies, which were also categorized into subgroups based on the moderator variable of intervention components. A random-effects model was used to combine studies within each subgroup, and a fixed-effect model was used to combine subgroups and yield the overall effect. The study-to-study variance was not assumed to be the same for all subgroups. This is the method used by Review Manager (RevMan).7 The odds ratio represented the odds of successfully avoiding HF readmissions, given exposure to an intervention involving 1 or more intervention components. A funnel plot of log odds ratio was created to test for publication bias.

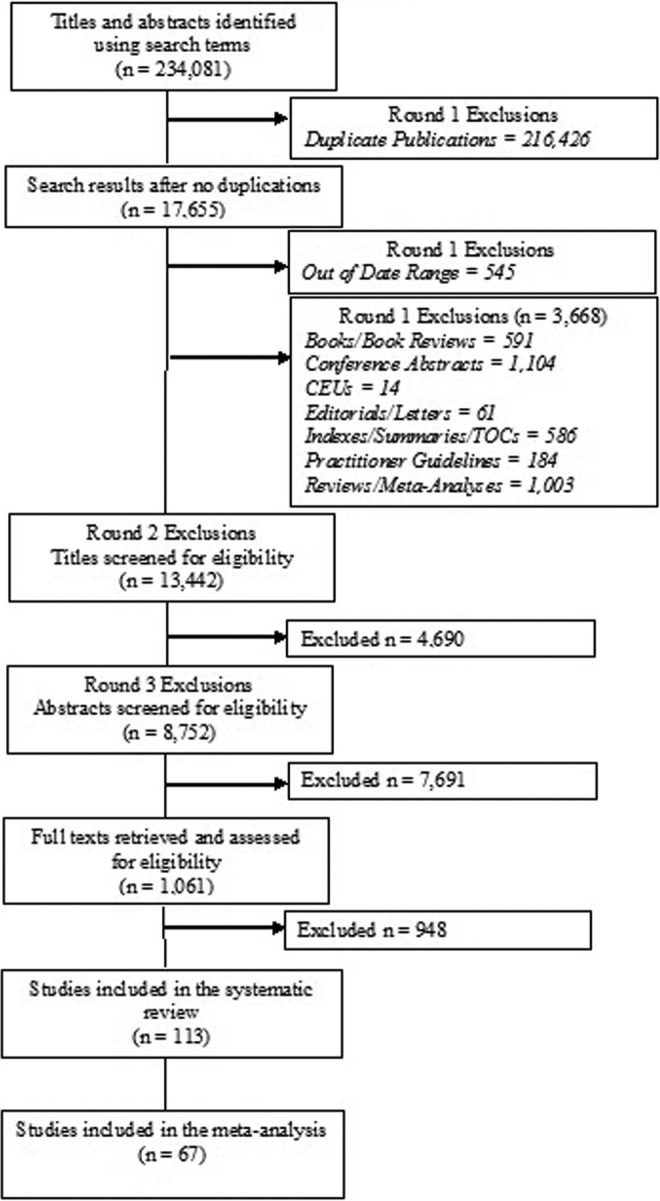

Results of Systematic Review

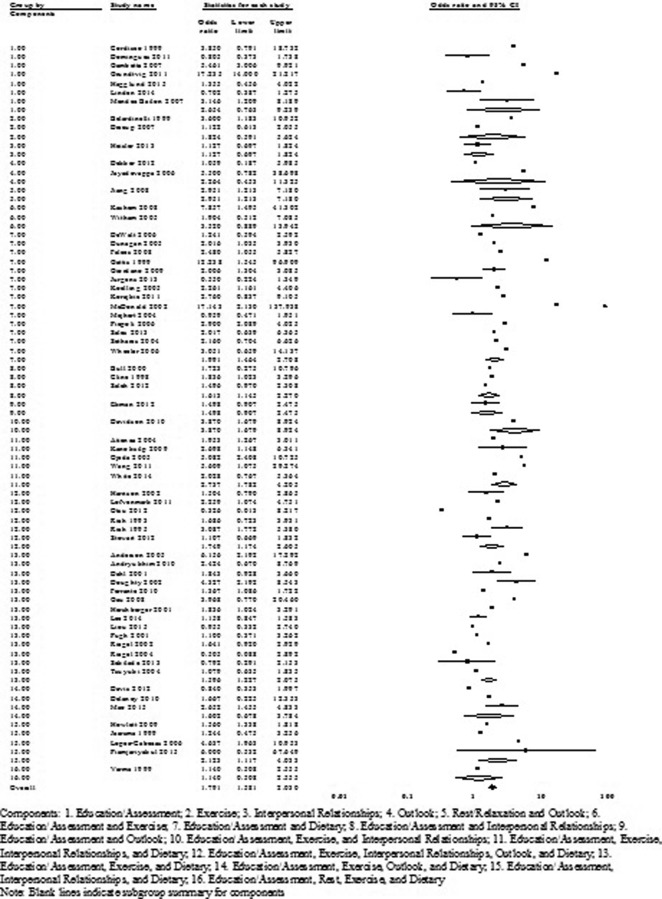

A flow diagram of the systematic review of literature is shown in Figure 1. The characteristics of the 113 included studies are shown in Appendix A. The interventions were grouped by components. Limited biases were introduced since only studies with proven quality were included. The empirical evidence provided by the systematic review is summarized in this section.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review of literature.

Education and Assessment

Eleven studies incorporated education and assessment.8–18 In 9 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

Patient education during hospitalization and postdischarge telemonitoring for reinforcement of education and assessment of patients13 or postdischarge home visits and monthly calls for reinforcement, assessment, and medication compliance8

Phone calls after discharge for patient education, assessment of symptoms and compliance, and review of medication adherence14

Postdischarge patient education at outpatient clinics and assessment of symptoms and compliance during clinic visits12 or during follow-up calls every 2 to 4 weeks16

Postdischarge assessments of medication adherence, symptoms/health, and compliance through a single home visit 1 week after discharge,18 through daily telemonitoring and outpatient clinic visits every 1 to 2 weeks,11 and through a daily telemonitoring system.9

Exercise

Four studies incorporated exercise.19–22 In all 4 studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

Interpersonal Relationships

Two studies incorporated interpersonal relationships.23,24 In these studies, readmissions were not significantly lowered.

Outlook

Two studies incorporated outlook.25,26 In these studies, readmissions were not significantly lowered.

Dietary Recommendations

Three studies incorporated dietary recommendations.27–29 In 2 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

A comparison of 2 groups, one with a low-sodium diet and the other with a medium-sodium diet. Both groups had 1000 mL/d fluid restriction and a high diuretic dose. The group with the medium-sodium diet showed a significant reduction in readmissions28

Eight different combinations of levels of fluid intake restriction, sodium intake, and diuretic dosages. A normal sodium diet with high diuretic doses and fluid intake restriction was most effective in reducing readmissions.29

Education and Assessment Combined With Exercise

Two studies incorporated these 2 components.30,31 In 1 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. This intervention included:

Patient education during hospitalization and postdischarge assessment of symptoms and compliance with emphasis on activity and treatment through Internet-based monitoring 3 times per week.30

Education and Assessment Combined With Interpersonal Relationships

Four studies incorporated these 2 components.32–35 In 2 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

Postdischarge education and counseling for patients and families to influence medication adherence through clinic visits and phone calls focused on incorporating significant others and building positive medication-taking behaviors.35

Education and Assessment Combined With Outlook

One study incorporated these 2 components.36 In this study, readmissions were not significantly lowered.

Education and Assessment Combined With Dietary Recommendations

Thirty studies incorporated these 2 components.37–65 In 16 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

Patient education during hospitalization and weekly or biweekly phone calls postdischarge to reinforce education and assess symptoms, compliance,62,63 and medication adherence45,58

Diet and self-care education during hospitalization and reinforcement of education and assessment of symptoms and compliance after discharge through weekly calls for 2 weeks,42 weekly calls for 12 weeks and 2 clinic visits,53 or calls and clinic visits tailored to individual patient needs55

Diet, disease, and drug therapy education at discharge and after discharge on monthly phone calls, clinic assessments, and using a pill counter43

Postdischarge phone calls weekly or biweekly for patient education39,40

Telemonitoring to assess diet, weight, symptoms,57 and medication adherence, along with home visits38

Patient education about symptoms and diet at discharge and after discharge over the phone, monthly home visits, and a daily diary for assessment of symptoms and compliance52

Postdischarge patient education on HF and diet at outpatient clinics, assessment of symptoms and compliance during clinic visits, and monitoring diet and/or medication adherence on calls47,64 or through the use of a diary and printed guide.50

Rest and Relaxation Combined With Outlook

One study incorporated these 2 components.66 In this study, readmissions were significantly lowered. This intervention included:

Relaxation therapy consisting of relaxation training and music therapy for 1 hour daily and basic psychological care lasting 4 weeks.66

Exercise Combined With Outlook

One study incorporated these 2 components.67 In this study, readmissions were not significantly lowered.

Education and Assessment Combined With Exercise and Interpersonal Relationships

One study incorporated these 3 components.68 In this study, readmissions were significantly lowered. This intervention included:

A cardiac rehabilitation program for 12 weeks with individualized exercise plans and group-based educational session for patients and families.68

Education and Assessment Combined With Exercise and Dietary Recommendations

Twenty-two studies incorporated these 3 components.69–90 In 12 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

Comprehensive patient education during hospitalization and a follow-up call 1 to 2 weeks after discharge76 and at 90 days for high-risk patients72

Patient education during hospitalization and postdischarge assessment of symptoms and compliance with emphasis on diet, activity, and treatment through biweekly phone calls74

Comprehensive patient education during hospitalization and postdischarge reinforcement and assessment of symptoms and compliance emphasizing diet, activity, and treatment through home visits at least once weekly for 6 weeks70

Postdischarge clinic visits and phone calls at 6-month intervals to provide patient education and assess symptoms and compliance86

Patient education postdischarge during 2 to 5 clinic visits and assessment of symptoms, compliance, and medication use through follow-up phone calls77 or through the use of a diary and/or pill counter,73 as well as motivational interviewing,81 or during monthly home visits with follow-up phone calls every 10 to 15 days89

One home visit during the first 2 weeks after discharge to provide patient education on self-management, diet, and physical activity and assess medication adherence and/or symptoms69 and follow-up phone calls at 3 and 6 months for assessment85

Education on self-care management, diet, and exercise delivered by a multidisciplinary team weekly for 6 weeks with a 1-hour exercise component.78

Education and Assessment Combined With Interpersonal Relationships and Dietary Recommendations

Six studies incorporated these 3 components.91–96 In 4 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

Postdischarge education on diet and sodium restriction for patients and caregivers through weekly outpatient clinic visits92 or coaching phone calls96

Education on HF, diet, and drug therapy for patients and caregivers at discharge and postdischarge on monthly phone calls, clinic assessments, and medication checklist94

Development of care plan and patient and caregiver education by a multidisciplinary team during hospitalization and weekly home visits to reinforce education and assess symptoms and compliance for 9 weeks postdischarge.95

Education and Assessment Combined With Outlook and Dietary Recommendations

Two studies incorporated these 3 components.97,98 In these studies, readmissions were not significantly lowered.

Education and Assessment Combined With Rest and Relaxation, Exercise, and Dietary Recommendations

One study incorporated the 4 components.99 In this study, readmissions were significantly lowered. This intervention included:

Pharmaceutical care, education about self-care, drugs, and medication, and 1 month of self-monitoring diary cards to record medication use, physical activity, diet, and symptoms.99

Education and Assessment Combined With Exercise, Interpersonal Relationships, and Dietary Recommendations

Eight studies incorporated these 4 components.100–107 In 6 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

Educational programs in clinics for patients and families102,103

Predischarge education on self-monitoring, diet, exercise, and medication and interview of patients and caregivers by nurse and postdischarge outpatient clinic visits every 3 months to review performance and introduce strategies to improve treatment adherence and response100

Comprehensive patient education with families/caregivers during hospitalization and postdischarge reinforcement and assessment of symptoms and compliance emphasizing diet, activity, and treatment through clinic visits every 3 months106 or clinic visits and phone calls every 2 to 8 weeks101

Home visit once during the first month after discharge for education on self-management, diet, physical activity, and vaccinations for the patient and caregiver, and pill organizers provided for medication adherence.104

Education and Assessment Combined With Exercise, Outlook, and Dietary Recommendations

Three studies incorporated these 4 components.108–110 In 1 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. This intervention included:

A multidisciplinary disease management program to provide in-person education to patients when enrolled in the intervention and through follow-up, which included outpatient clinic visits and monthly telephone calls and then visits every few months beginning at 6 months if patients had stabilized.110

Education and Assessment Combined With Exercise, Interpersonal Relationships, Outlook, and Dietary Recommendations

Nine studies incorporated these 5 components.111–119 In 2 of these studies, readmissions were significantly lowered. These interventions included:

A telehealth system that combined self-monitoring and motivational support tools in addition to a comprehensive, multidisciplinary HF care program112

Patient education about HF, medication, diet, and activity during hospitalization, at discharge, or after discharge during home visits and phone calls, which also included assessment of diet, weight, and medication checklist117

Education and Assessment Combined With Rest and Relaxation, Exercise, Interpersonal Relationships, Outlook, and Dietary Recommendations

One study incorporated these 6 components.120 In this study, readmissions were not significantly lowered.

Results of Meta-Analysis

A meta-analysis allowed for the combination of data from 67 studies to determine the impact of single or combined intervention components aiming to reduce HF readmissions. Studies included in the systematic review could not be included in the meta-analysis if only the total number of readmissions per group was reported, if multiple intervention groups were assessed, or if only composite outcomes were reported. Figure 2 shows the forest plot of the effect sizes and confidence intervals for each study in the fixed-effect and random-effects models. In the mixed-effects model, the overall odds of being readmitted were 1.79 times lower among participants of interventions that involved any of these intervention components. The funnel plot of log odds ratio was symmetrical, which indicates that publication bias was unlikely.121

Figure 2.

Forest plot of odds ratios for heart failure (HF) readmission in included studies.

Discussion and Conclusions

This analysis yields robust results that are based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies that evaluate interventions involving particular components aimed at reducing HF readmissions. Intervention strategies incorporating certain human factors or combinations of such factors have the potential to enhance therapeutic outcomes for HF patients following hospitalization. The implications of the key findings are as follows:

The independent and combined effects of education and assessment are the most beneficial strategies to yield a positive benefit to avoid or reduce readmissions of HF patients. A care management or disease management team could consider a person-centered approach to enhance individual choice or self-efficacy for the patients.

Exercise combined with education and assessment or rest and relaxation shows greater benefits than exercise alone. A clinical team could examine how activities were prescribed, implemented, and evaluated. Lack of adherence to or uncertainty about prescribed activities for the therapeutic outcomes may have prevented activities from demonstrating their beneficial effects on readmissions.

Nutrition combined with other intervention components reveals a clear positive effect. Dietary interventions should be combined with other strategies in order to maximize their benefit in the reduction of risk for HF readmissions.

Interventions with the aforementioned components increase the likelihood of not being readmitted to the hospital for HF. The meta-analysis results indicate that an intervention involving 1 or more of these components doubles an individual’s probability of not being readmitted.

This study is not without limitations. Potential limitations include the risk of bias at the study level and the possibility of incomplete retrieval of studies that meet the criteria. Furthermore, consideration should be given to other human factors and information technology that may facilitate patient–provider communications and coordinated care for chronic conditions as effective care modalities are developed and implemented for HF care management. This study focused on therapeutic interventions that incorporated certain human factors; therefore, comparison of these interventions to those not incorporating human factors was beyond the scope of this analysis. Overall, this research may help reconfigure the design, implementation, and evaluation of clinical practice for reducing HF readmissions in the future.

Author Biographies

Thomas T. H. Wan, PhD, is a professor and associate dean for Research in the College of Health and Public Affairs at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, Florida. He received his PhD in Sociology/Demography (1970) from University of Georgia and MHS in Social Epidemiology (1971) at the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health. He served on the faculties of Cornell University, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Virginia Commonwealth University. He has published 13 books and 200+ articles and book chapters in the fields of health services research and evaluation, health and aging, long-term care, etc.

Amanda Terry, PhD, is a Research Scientist at the Florida Hospital Translational Research Institute in Orlando, Florida. She received her PhD in Public Affairs (2016) from the University of Central Florida.

Enesha Cobb, MD, is a Research Scientist at the Florida Hospital Translational Research Institute in Orlando, Florida. She earned her MD (2007) from Johns Hopkins, MA in Theological Studies (2006), and MS in Health and Health Research (2013) from the University of Michigan.

Bobbie McKee, PhD, is a Research Associate in the College of Health and Public Affairs at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, Florida. She received her PhD in Public Affairs (2016).

Rebecca Tregerman is a MS-HSA Candidate in the College of Health and Public Affairs at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, Florida. She is a graduate research assistant for the project.

Sara D. S. Barbaro is a MS-HSA Candidate in the College of Health and Public Affairs at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, Florida. She is a graduate research assistant for the project.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Authors | Year | Country | Sample (Intervention) | Sample (Control) | Setting | Timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brotons et al.8 | 2009 | Spain | 144 | 139 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Cordisco et al.9 | 1999 | US | 30 | 51 | After discharge | 1 year |

| Domingues et al.10 | 2011 | Brazil | 48 | 63 | During hospitalization | 3 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Gambetta et al.11 | 2007 | US | 158 | 124 | After discharge | 7 months |

| Grundtvig et al.12 | 2011 | Norway | 1169 | N/A | After discharge | 12 months |

| Hagglund et al.13 | 2015 | Sweden | 32 | 40 | After discharge | 3 months |

| Hudson et al.14 | 2005 | US | 91 | N/A | After discharge | 6 months |

| Linden et al.15 | 2014 | US | 128 | 129 | During hospitalization | 30, 90 days |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Bailón et al.16 | 2007 | Spain | 51 | 131 | During discharge | 90 days |

| Miller & Cox17 | 2005 | US | 68 | N/A | After discharge | 90 days, 1 year |

| Stewart et al.18 | 1998 | Australia | 49 | 48 | After discharge | 6 months |

| Belardinelli et al.19 | 1999 | US | 50 | 49 | After discharge | 14 months |

| Dracup et al.20 | 2007 | US | 86 | 87 | After discharge | 3, 6, 12 months |

| Evangelista et al.21 | 2006 | US | 48 | 51 | After discharge | 6 months |

| Zeitler et al.22 | 2015 | US | 1159 | 1172 | After discharge | Every 3 months for 2 years |

| Heisler et al.23 | 2013 | US | 135 | 131 | During hospitalization | 12 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Li et al.24 | 2012 | US | 202 | 205 | During hospitalization | 60 days |

| Dekker et al.25 | 2012 | US | 21 | 20 | During hospitalization | 3 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Jayadevappa et al.26 | 2006 | US | 13 | 10 | After discharge | 6 months |

| Albert et al.27 | 2013 | US | 20 | 26 | After discharge | 60 days |

| Parrinello et al.28 | 2009 | Italy | A=87 | N/A | After discharge | 12 months |

| B=86 | ||||||

| Paterna et al.29 | 2009 | Italy | A=52, B=51, C=51, D=51, E=52, F=50, G=52, H=51 | N/A | After discharge | 6 months |

| Kashem et al.30 | 2008 | US | 24 | 24 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Witham et al.31 | 2005 | UK | 41 | 41 | After discharge | 6 months |

| Bull et al.32 | 2000 | US | 40 | 71 | During hospitalization | 2 weeks, 2 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Cline et al.33 | 1998 | Sweden | 80 | 110 | During hospitalization | 12 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Saleh et al.34 | 2012 | US | 173 | 160 | During discharge | 12 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Wu et al.35 | 2012 | US | A=27 | 28 | After discharge | 9 months |

| B=27 | ||||||

| Ekman et al.36 | 2012 | Sweden | 125 | 123 | During hospitalization | 6 months |

| Aldamiz-Echevarria Iraúrgui et al.37 | 2007 | Spain | 137 | 142 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Benatar et al.38 | 2003 | US | 108 | 108 | After discharge | 3 months |

| Brandon et al.39 | 2009 | US | 10 | 10 | After discharge | 12 weeks |

| Chen et al.40 | 2010 | Taiwan | 275 | 275 | After discharge | 6 months |

| DeWalt et al.41 | 2006 | US | 59 | 64 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Dunagan et al.42 | 2005 | US | 76 | 75 | After discharge | 6, 12 months |

| Falces et al.43 | 2008 | Spain | 53 | 50 | During discharge | 6, 12 months |

| Gattis et al.44 | 1999 | US | 90 | 91 | After discharge | 2, 12, 24 weeks |

| Giordano et al.45 | 2009 | Italy | 230 | 230 | During hospitalization | 12 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Goldberg et al.46 | 2003 | US | 138 | 142 | During discharge | 6 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Ho et al.47 | 2007 | Taiwan | 247 | N/A | After discharge | 139 ± 96 days |

| Jaarsma et al.48 | 2008 | Netherlands | A=340 | 339 | After discharge | 18 months |

| B=344 | ||||||

| Jurgens et al.49 | 2013 | US | 48 | 51 | During discharge | 90 days |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Korajkic et al.50 | 2011 | Australia | 35 | 35 | After discharge | 3 months |

| Koelling et al.51 | 2005 | US | 107 | 116 | During discharge | 180 days |

| Lee et al.52 | 2013 | US | 23 | 21 | After discharge | 3 months |

| McDonald et al.53 | 2002 | Ireland | 51 | 47 | During hospitalization | 3 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Mejhert et al.54 | 2004 | Sweden | 103 | 105 | After discharge | 18 months |

| Piepoli et al.55 | 2006 | Italy | 509 | N/A | After discharge | 12 months |

| Roig et al.56 | 2006 | Spain | 61 | N/A | After discharge | 11±10 months |

| Roth et al.57 | 2004 | Israel | 118 | N/A | After discharge | 12 months |

| Sales et al.58 | 2013 | US | 70 | 67 | During hospitalization | 30 days |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Sethares & Elliott59 | 2004 | US | 33 | 37 | During hospitalization | 3 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Shao & Yeh60 | 2010 | Taiwan, China | 93 | N/A | After discharge | 1 month |

| Sisk et al.61 | 2006 | US | 203 | 203 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Slater et al.62 | 2008 | US | 612 | N/A | During hospitalization | 6 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Wang et al.63 | 2014 | China | 32 | 34 | During hospitalization | 6 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| West et al.64 | 1997 | US | 51 | N/A | After discharge | 94-182 days |

| Wheeler & Waterhouse65 | 2006 | US | 20 | 20 | After discharge | 14 weeks |

| Jiang66 | 2008 | China | 101 | 89 | During hospitalization | 6 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Tully et al.67 | 2014 | Australia | A=15 | N/A | After discharge | 6 months |

| B=14 | ||||||

| Davidson et al.68 | 2010 | Australia | 52 | 53 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Aguado et al.69 | 2010 | Spain | 42 | 64 | After discharge | 24 months |

| Anderson et al.70 | 2005 | US | 44 | 77 | During hospitalization | 6 months |

| During discharge | ||||||

| After discharge | ||||||

| Andryukhin et al.71 | 2010 | Russia | 44 | 41 | After discharge | 6, 18 months |

| Dahl & Penque72 | 2001 | US | 381 | 203 | During hospitalization | 90 days |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Doughty et al.73 | 2002 | New Zealand | 100 | 97 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Ferrante et al.74 | 2010 | Argentina | 760 | 758 | After discharge | 1, 3 years |

| Gámez-López et al.75 | 2012 | Spain | A=25 | 35 | After discharge | 10.8 ± 3.2 months |

| B=28 | ||||||

| C=28 | ||||||

| Gau et al.76 | 2008 | Taiwan, China | 30 | 30 | During hospitalization | 1 month |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Hershberger et al.77 | 2001 | US | 108 | N/A | After discharge | 6 months |

| Houchen et al.78 | 2012 | UK | 17 | N/A | After discharge | 12 months |

| Lee et al.79 | 2014 | US | 473 | 475 | During hospitalization | 30 days |

| Liou et al.80 | 2015 | Taiwan | 56 | 75 | During hospitalization | 30, 90 days |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Pugh et al.81 | 2001 | US | 27 | 31 | During hospitalization | 12 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Riegel et al.82 | 2002 | US | 126 | 226 | After discharge | 3, 6 months |

| Riegel & Carlson83 | 2004 | US | 45 | 43 | After discharge | 30 days, 3 months |

| Smith et al.84 | 2015 | US | 92 | 106 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Stewart et al.85 | 1999 | Australia | 100 | 100 | After discharge | 6 months |

| Sun et al.86 | 2013 | China | 433 | 288 | After discharge | 4 years |

| Szkiladz et al.87 | 2013 | US | 86 | 94 | During discharge | 30 days |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Tsuyuki et al.88 | 2004 | Canada | 140 | 136 | During hospitalization | 6 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Vavouranakis et al.89 | 2003 | Greece | 28 | N/A | After discharge | 12 months |

| Wright et al.90 | 2003 | New Zealand | 100 | 97 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Dracup et al.91 | 2014 | US | A=200 | 209 | After discharge | 2 years |

| B=193 | ||||||

| Howlett et al.92 | 2009 | Canada | 990 | 7741 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Jaarsma et al.93 | 1999 | Netherlands | 84 | 95 | During hospitalization | 9 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| López Cabezas et al.94 | 2006 | Spain | 70 | 64 | During discharge | 12 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Naylor et al.95 | 2004 | US | 118 | 121 | During hospitalization | 52 weeks |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Piamjariyakul et al.96 | 2015 | US | 20 | N/A | After discharge | 6 months |

| Jerant et al.97 | 2001 | US | A=12 | 12 | After discharge | 6 months |

| B=13 | ||||||

| Shao et al.98 | 2013 | Taiwan | 47 | 46 | After discharge | 12 weeks |

| Varma et al.99 | 1999 | UK | 42 | 41 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Atienza et al.100 | 2004 | Spain | 164 | 174 | During hospitalization | 12 months |

| Fonarow et al.101 | 1997 | US | 214 | N/A | During hospitalization | 6 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Holst et al.102 | 2001 | Australia | 42 | N/A | During hospitalization | 6 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Kanoksilp et al.103 | 2009 | Thailand | 50 | 50 | After discharge | 12 months |

| Morcillo et al.104 | 2005 | Spain | 34 | 36 | After discharge | 6 months |

| Ojeda et al.105 | 2005 | Spain | 76 | 77 | After discharge | 16 ± 8 months |

| Wang et al.106 | 2011 | Taiwan, China | 14 | 13 | During hospitalization | 3 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| White & Hill107 | 2014 | US | 59 | N/A | During hospitalization | 2 months |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Davis et al.108 | 2012 | US | 63 | 62 | During hospitalization | 30 days |

| After discharge | ||||||

| Delaney & Apostolidis109 | 2010 | US | 12 | 12 | After discharge | 90 days |

| Mao et al.110 | 2015 | Taiwan | 174 | 175 | After discharge | Median 2 years |

| Byszewski et al.111 | 2010 | Canada | 45 | 46 | After discharge | 6 weeks |

| Domingo et al.112 | 2011 | Spain | A=48 | N/A | After discharge | 12 months |

| B=44 | ||||||

| Harrison et al.113 | 2002 | Canada | 92 | 100 | After discharge | 12 weeks |

| Löfvenmark et al.114 | 2011 | Sweden | 65 | 63 | After discharge | 18 months |

| Otsu & Moriyama115 | 2012 | Japan | 47 | 47 | After discharge | 7-12, 24 months |

| Rich et al.116 | 1993 | US | 63 | 35 | During hospitalization | 90 days |

| During discharge | ||||||

| After discharge | ||||||

| Rich et al.117 | 1995 | US | 142 | 140 | During hospitalization | 90 days |

| During discharge | ||||||

| After discharge | ||||||

| Stewart et al.118 | 2012 | Australia | 143 | 137 | After discharge | 18 months |

| Stewart et al.119 | 2014 | Australia | 137 | 143 | After discharge | 12-18 months |

| Sullivan et al.120 | 2009 | US | 108 | 100 | After discharge | 12 months |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. American Heart Association. Classes of heart failure. 2015. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartFailure/AboutHeartFailure/Classes-of-Heart-Failure_UCM_306328_Article.jsp#.Vs3iVpw4HIU. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- 2. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. ; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(1):e6–e245. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart failure fact sheet. 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fs_heart_failure.htm. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- 4. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355–363. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.216476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- 7. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA). Comprehensive meta-analysis 2009. http://www.meta-analysis.com/index.php. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- 8. Brotons C, Falces C, Alegre J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a home-based intervention in patients with heart failure: the IC-DOM study [in English, Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62(4):400–408. doi:10.1016/S1885-5857(09)71667-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cordisco ME, Beniaminovitz A, Hammond K, Mancini D. Use of telemonitoring to decrease the rate of hospitalization in patients with severe congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(7):860–862. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00452-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Domingues FB, Clausell N, Aliti GB, Dominguez DR, Rabelo ER. Education and telephone monitoring by nurses of patients with heart failure: randomized clinical trial [in English, Portuguese, Spanish]. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;96(3):233–239. doi:10.1590/S0066-782X2011005000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gambetta M, Dunn P, Nelson D, Herron B, Arena R. Impact of the implementation of telemanagement on a disease management program in an elderly heart failure cohort. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22(4):196–200. doi:10.1111/j.0889-7204.2007.06483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grundtvig M, Gullestad L, Hole T, Flønæs B, Westheim A. Characteristics, implementation of evidence-based management and outcome in patients with chronic heart failure results from the Norwegian Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(1):44–49. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hägglund E, Lyngå P, Frie F, et al. Patient-centred home-based management of heart failure. Findings from a randomised clinical trial evaluating a tablet computer for self-care, quality of life and effects on knowledge. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2015;49(4):193–199. doi:10.3109/14017431.2015.1035319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hudson LR, Hamar GB, Orr P. Remote physiological monitoring: clinical, financial, and behavioral outcomes in a heart failure population. Dis Manag. 2005;8(6):372–381. doi:10.1089/dis.2005.8.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Linden A, Butterworth SW. A comprehensive hospital-based intervention to reduce readmissions for chronically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(10):783–792. http://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2014/2014-vol20-n10/a-comprehensive-hospital-based-intervention-to-reduce-readmissions-for-chronically-ill-patients-a-randomized-controlled-trial/. Accessed March 15, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bailón MM, Rivas NM, Gutiérrez CP, Alonso CJ, de Oteyza CP, Mena LA. Manejo de la insuficiencia cardíaca en pacientes ancianos a través de la implantación de un hospital de día multidisciplinar [in Spanish]. Rev Clin Esp. 2007;207(11):555–558. doi:10.1157/13111573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miller LC, Cox KR. Case management for patients with heart failure: a quality improvement intervention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31(5):20–28. doi:10.3928/0098-9134-20050501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stewart S, Pearson S, Horowitz JD. Effects of a home-based intervention among patients with congestive heart failure discharged from acute hospital care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(10):1067–1072. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.10.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Belardinelli R, Georgiou D, Cianci G, Purcaro A. Randomized, controlled trial of long-term moderate exercise training in chronic heart failure: effects on functional capacity, quality of life, and clinical outcome. Circulation. 1999;99(9):1173–1182. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.99.9.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dracup K, Evangelista LS, Hamilton MA, et al. Effects of a home-based exercise program on clinical outcomes in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154(5):877–883. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Evangelista LS, Doering LV, Lennie T, et al. Usefulness of a home-based exercise program for overweight and obese patients with advanced heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(6):886–890. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zeitler EP, Piccini JP, Hellkamp AS, et al. ; HF-ACTION Investigators. Exercise training and pacing status in patients with heart failure: results from HF-ACTION. J Card Fail. 2015;21(1):60–67. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heisler M, Halasyamani L, Cowen ME, et al. Randomized controlled effectiveness trial of reciprocal peer support in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(2):246–253. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li H, Powers BA, Melnyk BM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of CARE: an intervention to improve outcomes of hospitalized elders and family caregivers. Res Nurs Health. 2012;35(5):533–549. doi:10.1002/nur.21491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dekker RL, Moser DK, Peden AR, Lennie TA. Cognitive therapy improves three-month outcomes in hospitalized patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012;18(1):10–20. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jayadevappa R, Johnson JC, Bloom BS, et al. Effectiveness of transcendental meditation on functional capacity and quality of life of African Americans with congestive heart failure: a randomized control study. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):72–77. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17274213. Accessed March 15, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Albert NM, Nutter B, Forney J, Slifcak E, Tang WHW. A randomized controlled pilot study of outcomes of strict allowance of fluid therapy in hyponatremic heart failure (SALT-HF). J Card Fail. 2013;19(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parrinello G, Di Pasquale P, Licata G, et al. Long-term effects of dietary sodium intake on cytokines and neurohormonal activation in patients with recently compensated congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009;15(10):864–873. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paterna S, Parrinello G, Cannizzaro S, et al. Medium term effects of different dosage of diuretic, sodium, and fluid administration on neurohormonal and clinical outcome in patients with recently compensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(1):93–102. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kashem A, Droogan MT, Santamore WP, Wald JW, Bove AA. Managing heart failure care using an internet-based telemedicine system. J Card Fail. 2008;14(2):121–126. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Witham MD, Gray JM, Argo IS, Johnston DW, Struthers AD, McMurdo ME. Effect of a seated exercise program to improve physical function and health status in frail patients ≥70 years of age with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(9):1120–1124. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bull MJ, Hansen HE, Gross CR. A professional-patient partnership model of discharge planning with elders hospitalized with heart failure. Appl Nurs Res. 2000;13(1):19–28. doi:10.1016/S0897-1897(00)80015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cline CM, Israelsson BY, Willenheimer RB, Broms K, Erhardt LR. Cost effective management programme for heart failure reduces hospitalisation. Heart. 1998;80(5):442–446. doi:10.1136/hrt.80.5.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saleh SS, Freire C, Morris-Dickinson G, Shannon T. An effectiveness and cost–benefit analysis of a hospital-based discharge transition program for elderly Medicare recipients. J Am Geriatr Soc.2012;60(6):1051–1056. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu JR, Corley DJ, Lennie TA, Moser DK. Effect of a medication-taking behavior feedback theory-based intervention on outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012;18(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ekman I, Wolf A, Olsson LE, et al. Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: the PCC-HF study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(9):1112–1119. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aldamiz-Echevarría Iraúrgui B, Muniz J, Rodriguez-Fernandez JA, et al. Randomized controlled clinical trial of a home care unit intervention to reduce readmission and death rates in patients discharged from hospital following admission for heart failure [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60(9):914–922. http://www.revespcardiol.org/en/randomized-controlled-clinical-trial-of/articulo/13114108/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Benatar D, Bondmass M, Ghitelman J, Avitall B. Outcomes of chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):347–352. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brandon AF, Schuessler JB, Ellison KJ, Lazenby RB. The effects of an advanced practice nurse led telephone intervention on outcomes of patients with heart failure. Appl Nurs Res. 2009;22(4):e1–e7. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen YH, Ho YL, Huang HC, et al. Assessment of the clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of the management of systolic heart failure in Chinese patients using a home-based intervention. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(1):242–252. doi:10.1177/147323001003800129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. DeWalt DA, Malone RM, Bryant ME, et al. A heart failure self-management program for patients of all literacy levels: a randomized, controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:30 doi:10.1186/1472-6963-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dunagan WC, Littenberg B, Ewald GA, et al. Randomized trial of a nurse-administered, telephone-based disease management program for patients with heart failure [in Spanish]. J Card Fail. 2005;11(5):358–365. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Falces C, López-Cabezas C, Andrea R, Arnau A, Ylla M, Sadurní J. Intervención educativa para mejorar el cumplimiento del tratamiento y prevenir reingresos en pacientes de edad avanzada con insuficiencia cardíaca. Med Clin. 2008;131(12):452–456. doi:10.1157/13126954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gattis WA, Hasselblad V, Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM. Reduction in heart failure events by the addition of a clinical pharmacist to the heart failure management team: results of the Pharmacist in Heart Failure Assessment Recommendation and Monitoring (PHARM) study. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(16):1939–1945. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.16.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Giordano A, Scalvini S, Zanelli E, et al. Multicenter randomised trial on home-based telemanagement to prevent hospital readmission of patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2009;131(2):192–199. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Goldberg LR, Piette JD, Walsh MN, et al. ; WHARF Investigators. Randomized trial of a daily electronic home monitoring system in patients with advanced heart failure: the Weight Monitoring in Heart Failure (WHARF) trial. Am Heart J. 2003;146(4):705–712. doi:10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ho YL, Hsu TP, Chen CP, et al. Improved cost-effectiveness for management of chronic heart failure by combined home-based intervention with clinical nursing specialists. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106(4):313–319. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jaarsma T, van der Wal MH, Lesman-Leegte I. Effect of moderate or intensive disease management program on outcome in patients with heart failure: Coordinating Study Evaluating Outcomes of Advising and Counseling in Heart Failure (COACH). Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(3):316–324. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2007.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jurgens CY, Lee CS, Reitano JM, Riegel B. Heart failure symptom monitoring and response training. Heart Lung. 2013;42(4):273–280. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Korajkic A, Poole SG, MacFarlane LM, Bergin PJ, Dooley MJ. Impact of a pharmacist intervention on ambulatory patients with heart failure: a randomised controlled study. J Pharm Pract Res. 2011;41(2):126–131. doi:10.1002/j.2055-2335.2011.tb00679.x. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koelling TM, Johnson ML, Cody RJ, Aaronson KD. Discharge education improves clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111(2):179–185. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000151811.53450.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lee KS, Lennie TA, Warden S, Jacobs-Lawson JM, Moser DK. A comprehensive symptom diary intervention to improve outcomes in patients with HF: a pilot study. J Card Fail. 2013;19(9):647–654. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McDonald K, Ledwidge M, Cahill J, et al. Heart failure management: multidisciplinary care has intrinsic benefit above the optimization of medical care. J Card Fail. 2002;8(3):142–148. doi:10.1054/jcaf.2002.124340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mejhert M, Kahan T, Persson H, Edner M. Limited long term effects of a management programme for heart failure. Heart. 2004;90(9):1010–1015. doi:10.1136/hrt.2003.014407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Piepoli MF, Villani GQ, Aschieri D, et al. Multidisciplinary and multisetting team management programme in heart failure patients affects hospitalisation and costing. Int J Cardiol. 2006;111(3):377–385. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Roig E, Pérez-Villa F, Cuppoletti A, et al. Programa de atención especializada en la insuficiencia cardíaca terminal. Experiencia piloto de una unidad de insuficiencia cardiac [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006;59(2):109–116. doi:10.1157/13084637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roth A, Kajiloti I, Elkayam I, Sander J, Kehati M, Golovner M. Telecardiology for patients with chronic heart failure: the ‘SHL’ experience in Israel. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97(1):49–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sales VL, Ashraf MS, Lella LK, et al. Utilization of trained volunteers decreases 30-day readmissions for heart failure. J Card Fail. 2013;19(12):842–850. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sethares KA, Elliott K. The effect of a tailored message intervention on heart failure readmission rates, quality of life, and benefit and barrier beliefs in persons with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2004;33(4):249–260. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shao JH, Yeh HF. The effectiveness of self-management programs for elderly people with heart failure. Tzu Chi Nurs J. 2010;9(1):71–79. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2015.06.004. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sisk JE, Hebert PL, Horowitz CR, McLaughlin MA, Wang JJ, Chassin MR. Effects of nurse management on the quality of heart failure care in minority communities: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):273–283. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Slater MR, Phillips DM, Woodard EK. Cost-effective care a phone call away: a nurse-managed telephonic program for patients with chronic heart failure. Nurs Econ. 2008;26(1):41–44. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/572312. Accessed March 15, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang XH, Qiu JB, Ju Y, et al. Reduction of heart failure rehospitalization using a weight management education intervention. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29(6):528–534. doi:10.1097/JCN.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. West JA, Miller NH, Parker KM, et al. A comprehensive management system for heart failure improves clinical outcomes and reduces medical resource utilization. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79(1):58–63. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00676-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wheeler EC, Waterhouse JK. Telephone interventions by nursing students: improving outcomes for heart failure patients in the community. J Community Health Nurs. 2006;23(3):137–146. doi:10.1207/s15327655jchn2303_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jiang LY. Psychological intervention to anxiety and depression in geriatric patients with chronic heart failure. Chin Ment Health J. 2008;22(11):829–832. http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-ZXWS200811012.htm. Accessed March 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tully PJ, Selkow T, Benge J, Rafanelli C. A dynamic view of comorbid depression and generalized anxiety disorder symptom change in chronic heart failure: the discrete effects of cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise, and psychotropic medication. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(7):585–592. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.935493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Davidson PM, Cockburn J, Newton PJ, et al. Can a heart failure-specific cardiac rehabilitation program decrease hospitalizations and improve outcomes in high-risk patients? EurJ Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17(4):393–402. doi:10.1097/HJR.0b013e328334ea56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Aguado O, Morcillo C, Delàs J, et al. Long-term implications of a single home-based educational intervention in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2010;39(6):S14–S22. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Anderson C, Deepak BV, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Zarich S. Benefits of comprehensive inpatient education and discharge planning combined with outpatient support in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2005;11(6):315–321. doi:0.1111/j.1527-5299.2005.04458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Andryukhin A, Frolova E, Vaes B, Degryse J. The impact of a nurse-led care programme on events and physical and psychosocial parameters in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial in primary care in Russia. Eur J Gen Pract. 2010;16(4):205–214. doi:10.3109/13814788.2010.527938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dahl J, Penque S. The effects of an advanced practice nurse-directed heart failure program. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2001;20(5):20–28. doi:10.1097/00003465-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Doughty RN, Wright SP, Pearl A, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of integrated heart failure management: the Auckland Heart Failure Management Study. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(2):139–146. doi:10.1053/euhj.2001.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ferrante D, Varini S, Macchia A, et al. ; GESICA Investigators. Long-term results after a telephone intervention in chronic heart failure: DIAL (Randomized Trial of Phone Intervention in Chronic Heart Failure) follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(5):372–378. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gámez-López AL, Bonilla-Palomas JL, Anguita-Sánchez M, Castillo-Domínguez JC, Crespín-Crespín M, Suárez de Lezo J. Influencia pronóstica de diferentes programas de intervención extrahospitalaria en pacientes ingresados por insuficiencia cardiaca con disfunción sistólica. Cardiocore. 2012;47(1):e1–e5. doi:10.1016/j.carcor.2011.01.008. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gau J, Ting C, Yeh M, Chang T. The effectiveness of comprehensive care programs at improving self-care and quality of life and reducing rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Evid Based Nurs. 2008;4(3):233–242. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2015.06.004. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hershberger RE, Ni H, Nauman DJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of an outpatient heart failure management program. J Card Fail. 2001;7(1):64–74. doi:10.1054/jcaf.2001.21677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Houchen L, Watt A, Boyce S, Singh S. A pilot study to explore the effectiveness of “early” rehabilitation after a hospital admission for chronic heart failure. Physiother Theory Pract. 2012;28(5):355–358. doi:0.3109/09593985.2011.621015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lee JH, Kim SJ, Lam J, Kim S, Nakagawa S, Yoo JW. The effects of shared situational awareness on functional and hospital outcomes of hospitalized older adults with heart failure. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:259–265. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S62269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Liou HL, Chen HI, Hsu SC, Lee SC, Chang CJ, Wu MJ. The effects of a self-care program on patients with heart failure. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015;78(11):648–656. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pugh LC, Havens DS, Xie S, Robinson JM, Blaha C. Case management for elderly persons with heart failure: the quality of life and cost outcomes. Med Surg Nurs. 2001;10(2):71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Riegel B, Carlson B, Glaser D, Kopp Z, Romero TE. Standardized telephonic case management in a Hispanic heart failure population: an effective intervention. Dis Manag Health Out. 2002;10(4):241–249. doi:10.2165/00115677-200210040-00006. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Riegel B, Carlson B. Is individual peer support a promising intervention for persons with heart failure? J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19(3):174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Smith CE, Piamjariyakul U, Dalton KM, Russell C, Wick J, Ellerbeck EF. Nurse-led multidisciplinary heart failure group clinic appointments: methods, materials, and outcomes used in the clinical trial. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;4(1):S25–S34. doi:10.1097/JCN.0000000000000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Stewart S, Marley JE, Horowitz JD. Effects of a multidisciplinary, home-based intervention on planned readmissions and survival among patients with chronic congestive heart failure: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 1999;354(9184):1077–1083. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sun LN, Wang NF, Zhong YG, et al. Curative effects on standardized management of community patients with coronary heart disease complicated with chronic heart failure [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;93(30):2341–2344. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2013.30.002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Szkiladz A, Carey K, Ackerbauer K, Heelon M, Friderici J, Kopcza K. Impact of pharmacy student and resident-led discharge counseling on heart failure patients. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(6):574–579. doi:10.1177/0897190013491768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tsuyuki RT, Fradette M, Johnson JA, et al. A multicenter disease management program for hospitalized patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10(6):473–480. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Vavouranakis I, Lambrogiannakis E, Markakis G, et al. Effect of home-based intervention on hospital readmission and quality of life in middle-aged patients with severe congestive heart failure: a 12-month follow up study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2(2):105–111. doi:10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Wright SP, Walsh H, Ingley KM, et al. Uptake of self-management strategies in a heart failure management programme. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5(3):371–380. doi:10.1016/S1388-9842(03)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Dracup K, Moser DK, Pelter MM, et al. Randomized, controlled trial to improve self-care in patients with heart failure living in rural areas. Circulation. 2014;130(3):256–264. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Howlett JG, Mann OE, Baillie R, et al. Heart failure clinics are associated with clinical benefit in both tertiary and community care settings: data from the improving Cardiovascular Outcomes in Nova Scotia (ICONS) Registry. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(9):e306–e311. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70141-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Jaarsma T, Halfens R, Huijer Abu-Saad H, et al. Effects of education and support on self-care and resource utilization in patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(9):673–682. doi:10.1053/euhj.1998.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. López-Cabezas C, Salvador CF, Quadrada DC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a postdischarge pharmaceutical care program vs. regular follow-up in patients with heart failure [in English, Spanish]. Farm Hosp. 2006;30(6):328–342. doi:10.1016/S1130-6343(06)74004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675–684. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Piamjariyakul U, Werkowitch M, Wick J, Russell C, Vacek JL, Smith CE. Caregiver coaching program effect: reducing heart failure patient rehospitalizations and improving caregiver outcomes among African Americans. Heart Lung. 2015;44(6):466–473. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Jerant AF, Azari R, Nesbitt TS. Reducing the cost of frequent hospital admissions for congestive heart failure: a randomized trial of a home telecare intervention. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1234–1245. doi:10.1097/00005650-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Shao JH, Chang AM, Edwards H, Shyu YI, Chen SH. A randomized controlled trial of self-management programme improves health-related outcomes of older people with heart failure. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(11):2458–2469. doi:10.1111/jan.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Varma S, McElnay JC, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, Varma M. Pharmaceutical care of patients with congestive heart failure: interventions and outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19(7):860–869. doi:10.1592/phco.19.10.860.31565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Atienza F, Anguita M, Martinez Alzamora N, et al. ; PRICE Study Group. Multicenter randomized trial of a comprehensive hospital discharge and outpatient heart failure management program. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6(5):643–652. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Fonarow GC, Stevenson LW, Walden JA, et al. Impact of a comprehensive heart failure management program on hospital readmission and functional status of patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(3):725–732. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Holst DP, Kaye D, Richardson M, et al. Improved outcomes from a comprehensive management system for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3(5):619–625. doi: 10.1016/S1388-9842(01)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kanoksilp A, Hengrussamee K, Wuthiwaropas P. A comparison of one-year outcome in adult patients with heart failure in two medical setting: heart failure clinic and daily physician practice. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(4):466–470. doi:10.1.1.594.1187&type=cc. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Morcillo C, Valderas JM, Aguado O, Delás J, Sort D. Evaluation of a home-based intervention in heart failure patients. Results of a randomized study [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(6):618–625. doi:10.1016/S1885-5857(06)60247-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Ojeda S, Anguita M, Delgado M, et al. Short- and long-term results of a programme for the prevention of readmissions and mortality in patients with heart failure: are effects maintained after stopping the programme? Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(5):921–926. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Wang SP, Lin LC, Lee CM, Wu SC. Effectiveness of a self-care program in improving symptom distress and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients: a preliminary study. J Nurs Res. 2011;19(4):257–266. doi:10.1097/JNR.0b013e318237f08d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. White SM, Hill A. A heart failure initiative to reduce the length of stay and readmission rates. Prof Case Manag. 2014;19(6):276–284. doi:10.1097/NCM.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Davis KK, Mintzer M, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, Hayat MJ, Rotman S, Allen J. Targeted intervention improves knowledge but not self-care or readmissions in heart failure patients with mild cognitive impairment. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(9):1041–1049. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfs096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Delaney C, Apostolidis B. Pilot testing of a multicomponent home care intervention for older adults with heart failure: an academic clinical partnership. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(5):E27–E40. doi:10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181da2f79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Mao CT, Liu MH, Hsu KH, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary disease management for hospitalized heart failure under a national health insurance programme. J Cardiovasc Med. 2015;16(9):616–624. doi:10.2459/JCM.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Byszewski A, Azad N, Molnar FJ, Amos S. Clinical pathways: adherence issues in complex older female patients with heart failure (HF). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(2):165–170. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Domingo M, Lupón J, González B, et al. Noninvasive remote telemonitoring for ambulatory patients with heart failure: effect on number of hospitalizations, days in hospital, and quality of life. CARME (CAtalan Remote Management Evaluation) study [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2011;64(4):277–285. doi:10.1016/j.recesp.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Harrison MB, Browne GB, Roberts J, Tugwell P, Gafni A, Graham ID. Quality of life of individuals with heart failure: a randomized trial of the effectiveness of two models of hospital-to-home transition. Med Care. 2002;40(4):271–282. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12021683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Löfvenmark C, Karlsson MR, Billing E, Mattiasson AC. A group-based multi-professional education programme for family members of patients with chronic heart failure: effects on knowledge and patients’ health care utilization. Patient Edu Couns. 2011;85(2):e162–e168. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Otsu H, Moriyama M. Follow-up study for a disease management program for chronic heart failure 24 months after program commencement. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2012;9(2):136–148. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7924.2011.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Rich MW, Vinson JM, Sperry JC, et al. Prevention of readmission in elderly patients with congestive heart failure: results of a prospective, randomized pilot study. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(11):585–590. doi:10.1007/BF02599709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18):1190–1195. doi:10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Marwick TH, et al. Impact of home versus clinic-based management of chronic heart failure: the WHICH? (Which Heart Failure Intervention Is Most Cost-Effective & Consumer Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care) multicenter, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(14):1239–1248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Horowitz J D, et al. Prolonged impact of home versus clinic-based management of chronic heart failure: extended follow-up of a pragmatic, multicentre randomized trial cohort. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(3):600–610. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Sullivan MJ, Wood L, Terry J, et al. The Support, Education, and Research in Chronic Heart Failure Study (SEARCH): a mindfulness-based psychoeducational intervention improves depression and clinical symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009;157(1):84–90. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed March 15, 2017. Updated March, 2011. [Google Scholar]