Abstract

Objective: The present study examined how expectations regarding aging (ERA) influence physical activity participation and physical function. Method: We surveyed 148 older adults about their ERA (ERA-38), health-promoting lifestyles (HPLP-II), and self-rated health (RAND-36). We tested the mediating effect of physical activity on the relationships between ERA and physical function. Results: Positive expectations were associated with more engagement in physical activity (B = 0.016, p < .05) and better physical function (B = 0.521, p < .01). Physical activity mediated the relationship between ERA and physical function (B = 5.890, p < .01, indirect effect 0.092, CI = [0.015, 0.239]). Discussion: ERA play an important role in adoption of physically active lifestyles in older adults and may influence health outcomes, such as physical function. Future research should evaluate whether attempts to increase physical activity are more successful when modifications to ERA are also targeted.

Keywords: older adults, expectations, aging, active life/physical activity, physical function, health

Health and Expectations Regarding Aging

Older adults are encouraged to use health-promoting resources and to participate in a healthy lifestyle (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013), but there is wide variability in the adoption of active lifestyles. Individual psychological characteristics are an understudied aspect of the successful adoption of healthy behaviors such as physical activity. In particular, we are interested in beliefs and expectations that individuals hold that may influence their adoption and maintenance of physical activity, which in turn may influence physical health. The present study aims to investigate the relationship between individuals’ expectations regarding aging and engagement in health behaviors (i.e., physical activity) and how both relate to physical health outcomes. Specifically, we are interested in examining if engagement in physical activity helps explain the relationship between expectations and physical function.

Expectations regarding aging (ERA) are defined as the beliefs that the persons have related to how well they will maintain their physical and cognitive health as they age (Sarkisian, Hays, Berry, & Mangione, 2002). These ERA indicate how successfully someone expects to age. Unfortunately, most older adults do not expect to age successfully (Sarkisian, Hays, & Mangione, 2002). Thus, researchers have begun to examine the relationship between ERA and health to better understand how beliefs about aging impact health.

There is a growing body of literature that supports the link between individuals’ ERA and physical health outcomes and mortality (Levy, Slade, Kunkel, & Kasl, 2002; Prohaska, Keller, Leventhal, & Leventhal, 1987; Rakowski & Hickey, 1992; Sarkisian, Hays, & Mangione, 2002; Sarkisian et al., 2001; Sarkisian, Prohaska, Wong, Hirsch, & Mangione, 2005). Levy et al. (2002) demonstrated that positive ERA are associated with better physical function while aging, as well as increased longevity. Positive ERA were also related to better self-reported physical and mental health, and this relationship between ERA and health was partially mediated by engagement in health-promoting behaviors such as physical activity, stress management, and interpersonal relations (Kim, 2009). Self-perception of aging can also influence individuals’ engagement in other health-promoting behaviors such as having regular physical examinations, eating a healthy balanced diet, limiting use of alcohol and/or tobacco, and participating in exercise, as well as their use of health care resources (Levy & Myers, 2004). More specifically, positive self-perceptions were associated with an increased likelihood of having a physical examination in the last 2 years as well as increased participation in strenuous physical activity (Meisner & Baker, 2013; Meisner, Weir, & Baker, 2013).

Previous research has shown that individuals that maintain negative age-related expectations underestimate their ability to engage in physical activity, thus accepting a more sedentary lifestyle (O’Brien Cousins, 2000, 2003). Similarly, older adults who believe that aging results in inevitable physical deterioration disengaged in physical activity (O’Brien Cousins, 2000, 2003). Sarkisian et al. (2005) examined the relationship between aging expectations and physical activity and found a significant positive association between aerobic activity and positive ERA: those with more negative expectations were less likely to report engaging in physical activity. Thus, negative ERA may act as a barrier to physical activity in this population (Sarkisian et al., 2005).

Resnick, Palmer, Jenkins, and Spellbring (2000) examined older adults’ efficacy expectations as it related to their ability to participate in physical activity despite facing challenges and barriers. Efficacy expectations are similar to ERA in that they not only take into account an individual’s expectation that something will happen, but they also account for the individual’s ability to achieve the expected outcome (i.e., efficacy). They found that efficacy expectations were related to older adults’ adherence to an exercise program consisting of 20 min of continuous aerobic exercise 3 times a week for 3 months. However, they also noted that efficacy expectations were related to exercise behavior indirectly, with outcome expectancy (i.e., belief that exercise will have positive effects on health as well as knowledge of the benefits it provides) helping to explain this relationship (Resnick et al., 2000). Their study demonstrates the importance of older adults’ perception of their ability to engage in physical activity (i.e., self-efficacy), as well as their knowledge of the health-related benefits exercise can provide.

Physical Activity and Health Outcomes in Older Adults

Modifiable health behaviors play an important role in the maintenance and improvement of health. One health behavior that has been widely researched is physical activity. There is an abundance of evidence that shows physical activity is important to health in older adults. Warburton, Nicol, and Bredin (2006) summarized the vast literature demonstrating the health benefits of regular physical activity including the primary and secondary prevention of several chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, hypertension, obesity, depression, and osteoporosis. They also reported a dose response relationship such that greater amounts of physical activity lead to greater improvements in health. Wen et al. (2011) demonstrated that older adults with and without disabilities benefited from minimal increases in physical activity, leading to reduced all-cause mortality. They noted that, although healthy individuals tend to exercise more, individuals with chronic health risk factors and conditions can still experience improvement in health (Wen et al., 2011).

Dogra and Stathokostas (2012) found that engagement in physical activity combined with a reduction in time spent in sedentary behaviors was related to the success with which older adults age across physical, psychological, and social domains. They created variables to measure physical health (i.e., functional impairment), psychological health (i.e., cognitive function, emotional vitality, and depression), and sociological health (i.e., engagement with life, social support, and spirituality). Those who spent more time walking per week were more likely to be classified as healthy in all three domains and were considered to be aging successfully across the three domains. Individuals who were the least sedentary, as measured by hours spent sitting per day, were also more likely to be classified as aging successfully (Dogra & Stathokostas, 2012).

ERA have been shown to influence the adoption of physical activity, and physical activity is strongly associated with better physical health outcomes, yet few studies have explicitly tested whether this chain of events explains the association between ERA and physical function (Kim, 2009; Levy et al., 2002; Prohaska et al., 1987; Rakowski & Hickey, 1992; Sarkisian, Hays, & Mangione, 2002; Sarkisian et al., 2001; Sarkisian et al., 2005). To better understand the possible mechanisms of this relationship, we examined physical activity as a mediator (Dogra & Stathokostas, 2012; Kim, 2009; Meisner & Baker, 2013; Meisner et al., 2013; Sarkisian et al., 2005; Warburton et al., 2006; Wen et al., 2011). In sum, we hypothesized that positive ERA would be associated with more self-reported physical activity, which would positively influence subjective physical function. We also hypothesized that self-reported physical activity would mediate this relationship. This relationship has yet to be studied using these variables in a population of community-dwelling older adults in the United States.

Method

Participants

Study participants were recruited from a pool of prior research participants from a research institute in the Midwestern United States, who gave consent to be contacted for future studies. Individuals were contacted by mail if they were age 60 or older. All participants had a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0, which is reflective of “normal” cognitive status (Morris, 1993). All eligible older adults were mailed study materials, and completed participant materials were received over a 2-month time period in 2015.

We mailed surveys to 233 potential participants and received responses from 148 participants (n = 98 women, n = 50 men) who ranged in age from 61 to 96 years old (M = 74.57, SD = 7.06). The majority of participants described their racial or ethnic identification as Caucasian (95.9%), followed by Black/African American (2.7%), and Asian (1.4%). The mean for years of education was 16.16 (SD = 2.52, range = 10-24). The majority of participants described their employment status as “retired” (54.7%), followed by “volunteer regularly” (26.4%), and “currently employed” (18.90%).

Measures

Background information form

A background information form was used to collect participants’ demographic information, including age, sex, education, ethnicity, and employment status.

Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

The GDS was designed to screen for depression and is a commonly used measure of depression in older adults. The 30-item scale assesses somatic complaints, cognitive complaints, motivation, self-image, agitation, and mood (Yesavage et al., 1983). Higher scores indicate more reported symptoms of depression. An alpha coefficient of .94 and a split-half reliability coefficient of .94 suggest that the survey has a high degree of internal consistency (Yesavage et al., 1983). As depression may influence participation in physical activity and perception of physical function, we included this as a covariate in the analysis. Participants completed the GDS, and total scores were used in the analysis as a covariate to account for level of depression.

Expectations Regarding Aging (ERA-38) Survey

The ERA-38 survey includes 38 questions related to physical and cognitive health as well as independence in activities of daily living. The ERA-38 was designed to measure the extent to which individuals expect to experience age-associated decline (Sarkisian, Hays, Berry, & Mangione, 2002). Internal consistency alpha coefficients for the subscales measured by the ERA-38 range from .73 to .94, with exception of the Pain subscale (α = .58; Sarkisian, Hays, Berry, & Mangione, 2002). The survey addresses domains including sleep and fatigue, pain, sexual function, urinary incontinence, and physical appearance. Higher scores indicate a higher expectation to achieve successful aging, and lower scores indicate expected physical and mental decline. Participants completed the ERA-38 as a measure of ERA, and total scores were used in the analysis.

Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP-II)

The HPLP-II consists of 52 questions related to current engagement in health-promoting lifestyle factors (Walker, Sechrist, & Pender, 1995). These lifestyle factors are quantified using six subscales (i.e., Health Responsibility, Physical Activity, Nutrition, Spiritual Growth, Interpersonal Relations, and Stress Management). The construct validity of these subscales was analyzed using factor analysis, which confirmed the six-dimensional structure of the HPLP-II (Walker & Hill-Polerecky, 1996). The HPLP-II has an alpha coefficient of .94, and the subscales have alpha coefficients ranging from .79 to .87, suggesting that the measure and its subscales are internally consistent (Walker & Hill-Polerecky, 1996). A total score can also be calculated by scoring responses to all of the items on the survey (i.e., items from every subscale).

Participants completed the full HPLP-II as a part of a larger study, although the present study uses the subscales relevant to the present hypotheses. For the purpose of this study, the Physical Activity subscale was used as an indicator of the participant’s level of physical activity. Questions on the Physical Activity subscale inquire about the use of a planned exercise program; frequency of vigorous, moderate, and leisure-time activity; and the use of stretching and activities of daily living for the purpose of exercise. Two questions inquire about the use of heart rate monitoring during physical activity.

RAND 36-Item Health Survey (RAND-36)

The RAND-36 is one of the most widely used measures of health-related quality of life (Hays & Morales, 2001). It can be used to examine how health affects general functioning and perceived physical, mental, and social well-being. The survey consists of eight subscales: Physical Functioning, Role Limitations due to Physical Health, Role Limitations due to Emotional Problems, Social Functioning, Emotional Well-Being, Energy/Fatigue, Pain, and General Health (Hays, Sherbourne, & Mazel, 1993). The RAND-36 survey’s alpha values range from .71 to .93, suggesting that the measure and its subscales are internally consistent, and confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the dimensions of the survey (Vander Zee, Sanderman, Heyink, & de Haes, 1996). A total score can be calculated by scoring responses to all of the items on the survey (i.e., items from every subscale). Participants completed the full RAND-36 as a part of a larger study. For the purposes of this study, the Physical Functioning subscale was used as an indicator of the participant’s ability to engage in physically demanding activities such as running, playing sports, doing indoor chores, lifting heavy objects, carrying groceries, climbing stairs, walking, and bathing.

Procedure

Potential participants were mailed consent forms and the study materials. Individuals who decided to participate sent their signed consent forms and completed study materials back to the researchers. A university institutional review board approved the study.

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted in SPSS (Version 22) (IBM Corp. Released, 2013). Mediation analyses were conducted using Hayes’ (2012) mediation macro PROCESS. For this study, bootstrapped confidence intervals were used to test the significance of the indirect effects, because bootstrapping makes fewer assumptions about the shape and normality of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect and because it is more powerful than the Sobel test (Hayes, 2012). Unstandardized regression coefficients preserve each scale’s units of measurement, and they were used to accurately reflect the change in one scale based on a one-unit change in another scale. Unstandardized coefficients also reduce bias due to sampling error because they do not require the use of the sample’s means and standard deviations (Hayes, 2009).

ERA-38 total scores were used, because we were interested in examining ERA generally across domains including sleep and fatigue, pain, sexual function, urinary incontinence, and physical appearance. The RAND-36 Physical Functioning subscale was used to measure participants’ ability to engage in physically demanding tasks and the HPLP-II Physical Activity subscale score was used as a measure of physical activity. We examined whether physical activity (HPLP-II Physical Activity subscale) mediated the relationship between ERA (ERA-38 total) and physical function (RAND-36 Physical Functioning subscale), while adjusting for age, sex, education, ethnicity, employment status, and level of depression. Multiple regression analyses were performed to test the mediating effect of physical activity on the relationships between ERA and physical function. To test the indirect effects of the hypothesized mediation model, we used bootstrapping (N = 5,000 samples).

Missing Data

Participants who did not respond to more than 10% of the total items on the ERA-38, HPLP-II, or the RAND-36 were excluded from the sample (n = 10). Responses were imputed using the hot-deck imputation method for participants missing less than 10% on the ERA-38 and the HPLP-II, using a participant that was matched based on sex, age, and level of depression (Andridge & Little, 2010).

Results

Mediation Analyses

Descriptive statistics for the GDS (total), ERA-38 (total), HPLP-II (Physical Activity subscale), and RAND-36 (Physical Functioning subscale) scores can be found in Table 1. All mediation analyses were conducted on the total sample (N = 148). The unstandardized regression coefficients and associated results are summarized in Table 2. The total, direct, and indirect effect coefficients are summarized in Table 3.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Scores on the GDS, ERA-38, HPLP-II, and RAND-36 (N = 148).

| Survey | Total or subscale score | Number of items | M | SD | Range | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDS | Total | 30 | 3.53 | 3.62 | 0.0-17.0 | 0.812 |

| ERA-38 | Total | 38 | 50.27 | 9.85 | 24.48-82.35 | 0.941 |

| HPLP-II | Physical Activity | 8 | 2.58 | 0.74 | 1.0-4.0 | 0.843 |

| RAND-36 | Physical Functioning | 10 | 77.64 | 21.23 | 15.0-100.0 | 0.880 |

Note. GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; ERA-38 = Expectation Regarding Aging–38; HPLP-II = Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II; RAND-36 = RAND 36-Item Health Survey.

Table 2.

Results of the Mediation Analysis Examining the Effect of Physical Activity on the Relationship Between Expectations and Physical Function.

| Path A: Physical activity | Path B: Physical functioning | Path C: Physical functioning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expectations (ERA-38) | 0.016* | 0.521** | 0.613** |

| Physical Activity (HPLP-II) | — | 5.890** | — |

| Depression (GDS) | −0.041** | −0.551 | −0.790 |

| Employment (unemployed = 0, employed = 1) | 0.113 | −1.422 | −0.755 |

| Sex (male = 0, female = 1) | −0.178 | −6.957* | −8.007* |

| Education (years) | 0.023 | −1.040 | −1.026 |

| Age (years) | 0.007 | −1.154*** | −1.112*** |

| Minority status (Caucasian = 0, Minority = 1) | 0.024 | −11.231 | −11.092 |

| F | 3.862*** | 9.181*** | 7.681*** |

| R 2 | 0.143 | 0.313 | 0.278 |

Note. Unstandardized regression coefficients (B) reported. ERA-38 = Expectation Regarding Aging–38; HPLP-II = Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale.

p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001.

Table 3.

Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects of the Mediation Analysis Examining the Effect of Physical Activity on the Relationship Between Expectations and Physical Function.

| Effect | Lower limit confidence interval | Upper limit confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.613** | 0.238 | 0.987 |

| Direct effect | 0.521** | 0.146 | 0.895 |

| Indirect effect (C′) | 0.092a | 0.015 | 0.239 |

Note. Indirect effect confidence interval is a bootstrapped estimate (5,000 samples). Indirect effects are considered significant if the associated confidence interval does not contain 0.

Significant indirect effect.

p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001.

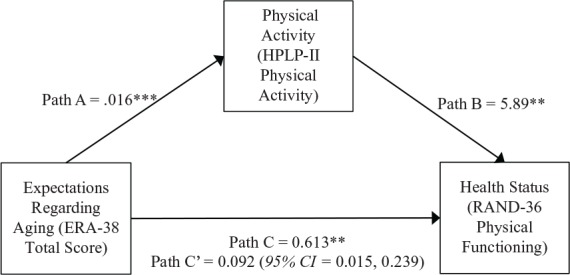

Our results (see Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 1) indicate that ERA was a significant predictor of engagement in physical activity, explaining a significant proportion of variance in physical activity scores, with more positive expectations being associated with more engagement in physical activity. ERA was also a significant predictor of physical function explaining a significant proportion of variance in RAND-36 Physical Functioning scores with more positive expectations being associated with higher levels of self-rated physical function. ERA and engagement in physical activity together predicted physical function, with HPLP-II physical activity scores explaining a significant proportion of variance in RAND-36 Physical Functioning scores; more positive expectations and more self-reported engagement in physical activity were associated with higher levels of self-rated physical function. ERA-36 total scores accounted for less of the variance in RAND-36 Physical Functioning scores after including HPLP-II physical activity scores. These results indicate that self-reported engagement in physical activity partially mediated the relationship between ERA and self-reported physical function, with the predictors accounting for 31.3% of the variance in physical function. These results indicated that the indirect effect coefficient was significant, because the confidence interval does not include 0.0. There is no reported p value associated with the indirect effect coefficient, because it does not meet the definition of a formal null hypothesis test (Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

Figure 1.

Mediation model: Relationship between expectations regarding aging, physical activity, and physical function.

Note. Unstandardized regression coefficients (B) reported for Paths A, B, and C. Indirect effect coefficient reported for C′. HPLP-II = Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II; ERA-38 = Expectation Regarding Aging–38; RAND-36 = RAND 36-Item Health Survey.

*p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001.

Discussion

The present study suggests that older adults who expected fewer age-related health problems (i.e., had more positive ERA) engaged in higher levels of physical activity and, in turn, viewed themselves as having higher levels of physical function; thus, older adults with more positive ERA are more likely to experience better physical function. This finding is congruent with the existing literature that supports the relationship between ERA and physical health (Kim, 2009; Levy et al., 2002; Prohaska et al., 1987; Rakowski & Hickey, 1992; Sarkisian, Hays, & Mangione, 2002; Sarkisian et al., 2001; Sarkisian et al., 2005). The results of our significant mediation model suggest that engagement in physical activity partially explains the relationship between ERA and physical function. This finding supports previous research that suggests that physical activity may be an important predictor of health in older adults (Dogra & Stathokostas, 2012; Warburton et al., 2006; Wen et al., 2011). It also supports the literature that suggests that more positive ERA are associated with increased engagement in physical activity (Kim, 2009; Meisner & Baker, 2013; Meisner et al., 2013; Sarkisian et al., 2005). These findings together support previous findings on the relationship between ERA, physical activity, and health (Levy et al., 2002; Meisner & Baker, 2013; Meisner et al., 2013; Sarkisian, Hays, & Mangione, 2002; Sarkisian et al., 2005), and they highlight the importance of addressing both ERA and engagement in physical activity when attempting to improve physical function. Although these findings support previous research, this relationship has not been previously studied in this way in a population of community-dwelling older adults in the United States.

One previous study highlighted the modifiable nature of ERA. Bardach, Gayer, Clinkinbeard, Zanjani, and Watkins (2010) used a positive aging intervention to improve individuals’ ERA. After participants were exposed to the idea of positive aging through the presentation of descriptive stories and photos of people who were aging positively, their ERA improved, as indicated by higher scores on the Expectations Regarding Aging–38 (ERA-38) survey. The stories were brief descriptions of older adults, ages 66 to 100, who were aging successfully. The researchers hypothesized that participants would examine their ERA and vision of themselves as an aging individual, and compare it with the successful agers described in the stories. By simply presenting a healthy view of aging, individuals scored higher on the ERA-38 indicate that they endorsed more positive ERA after the intervention (Bardach et al., 2010). Holahan, Holahan, Velasquez, and North (2008) found that individuals with more positive ERA at age 60 were happier later in life at ages 70, 75, and 80. This finding is important because it demonstrates that ERA may be modifiable. The present study shows the relationship between negative ERA, lower engagement in physical activity, and poorer physical function; thus, it may be beneficial to examine whether improving ERA positively affects engagement in health behaviors and health outcomes.

Our findings have important implications for interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in older adult populations. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in older adults, but few have examined how also targeting ERA may aid in improving outcomes or adherence. These interventions may be more effective if an expectation-improving component is included. One study demonstrated the effectiveness of teaching older adults to attribute sedentary behavior to modifiable attributes (Sarkisian, Prohaska, Davis, & Weiner, 2007). They hypothesized that older adults who attribute sedentary behaviors to old age would have more negative ERA (i.e., expect more age-related decline) and be more highly sedentary (Sarkisian et al., 2005). After the 4-week intervention, they observed an increase in mean steps per week. Their intervention also increased ERA, and participants noted improvement in mood, pain, energy, and sleep (Sarkisian et al., 2007).

A qualitative study examining older adults with somatic health problems (Helvik, Iversen, Steiring, and Hallberg, 2011) found that participants were most concerned with maintaining control and balance in their lives. Participants adjusted their expectations to their physical abilities, so that they could maintain a sense of control over their lives. Participants reported that they tried to be reasonable with their expectations, while trying to remain rational, in an attempt to avoid feeling depressed about their changing health. By learning more about the relationship between expectations and health, we may be able to more effectively increase health behaviors in older adult populations.

Understanding older adults’ expectations may also be a way to identify those at increased risk for depression or lack of engagement in health-promoting behaviors. Sellers, Bolender, and Crocker (2010) examined beliefs about aging qualitatively in a sample of older adults finding that some older adults believed that decline in physical health was unavoidable and a part of the aging process, further believing that that they could not maintain their health regardless of their attitude. By better understanding how ERA influence health behaviors and outcomes, we can be better prepared to intervene in older adult populations, to help promote healthier lifestyles.

Examining older adults’ expectations as they relate to health behaviors may also provide valuable information on how to design appropriate health-improving interventions for older adults. In our study, we found that more positive ERA across different domains including sleep and fatigue, pain, sexual function, urinary incontinence, and physical appearance were associated with more reported engagement in physical activity. However, we did not isolate specific expectations that were most strongly associated with an individual’s level of physical activity. By isolating such specific beliefs and expectations, health-improving interventions could be tailored to the individual with the goal of reducing barriers that are created by negative ERA. Hardy and Grogan (2009) conducted a qualitative study examining personal and social influences on participation in physical activity. They found that older adults desire to engage in physical activity because they expect that it will preserve and improve their health, but they also reported beliefs about their inability to engage in physical activity due to old age and frailty. Participants reported that they felt as though older adults’ needs are overlooked, in favor or targeting younger generations, and they mentioned being unable to find suitable facilities with appropriate exercise classes (Hardy & Grogan, 2009). Thus, examining older adults’ expectations as they relate to health behaviors, while also identifying practical barriers, may provide useful information about how to make health-promoting services more approachable to older adults. For example, an intervention aimed at increasing physical activity could address both the practical barriers older adults face (e.g., facility accessibility and access to suitable exercise classes) while also discussing how negative beliefs about aging (e.g., believing one is too frail or too old to exercise) contribute to reduced engagement in physical activity.

Negative expectations may also be a good indicator of individuals who are at greater risk for health decline due to lack of engagement in health-promoting behaviors. If an individual’s expectations are negative, researchers and clinicians may help motivate individuals to engage in physical activity using factors previously demonstrated to successfully motivate older adults. Janssen and Stube (2014) identified both intrinsic and extrinsic factors that contributed to older adults’ participation in physical activity. Older adults were motivated to exercise to maintain a sense of control over their health. Effective health educators who recommended manageable physical activity routines also helped motivated them, further identifying the need for clinicians who are educated about the needs of older adults (Janssen & Stube, 2014).

Limitations

A limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design. Because the data were collected at a single time-point and there was no random assignment or experimental manipulation, causal inferences about the relationships between ERA, health-promoting behaviors, and subjective health status cannot be made. We cannot rule out reverse causality; thus, we do not know if older adults with poorer health engage in fewer health-promoting behaviors or if older adults who engage in fewer health behaviors have poorer health as a result.

The sample was also largely made up of Caucasian females, limiting the generalizability of the study results. The data also may reflect nonresponse bias, due to the data collection procedure and use of convenience sampling, because participants who responded may have different characteristics than those who did not respond. Individuals that did not respond may have had poorer health, which may have generated a healthier sample than is representative of the overall population of older adults.

Future Directions

Our results suggest that interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in older adult populations may be more effective if an expectation-improving component is included. Future research should focus on interventions that help individuals develop more positive ERA, while also helping them increase their physical activity. Psychoeducational interventions that help inform older adults about the health-related benefits of physical activity are also needed, because older adults who understand the benefits of regular exercise may be more likely to adhere to interventions aimed at increasing physical activity or decreasing sedentary time (Resnick et al., 2000).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is supported by University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center P30AG035982.

References

- Andridge R. R., Little R. J. (2010). A review of hot deck imputation for survey non-response. International Statistical Review, 78, 40-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardach S. H., Gayer C. C., Clinkinbeard T., Zanjani F., Watkins J. F. (2010). The malleability of possible selves and expectations regarding aging. Educational Gerontology, 36, 407-424. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). The state of aging and health in America 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Dogra S., Stathokostas L. (2012). Sedentary behavior and physical activity are independent predictors of successful aging in middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Aging Research, 2012, Article 190654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S., Grogan S. (2009). Preventing disability through exercise investigating older adults’ influences and motivations to engage in physical activity. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 1036-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408-420. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- Hays R. D., Morales L. S. (2001). The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Annuals of Medicine, 33, 350-357. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays R. D., Sherbourne C. D., Mazel R. M. (1993). The RAND 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Economics, 2, 217-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helvik A. S., Iversen V. C., Steiring R., Hallberg L. R. (2011). Calibrating and adjusting expectations in life: A grounded theory on how elderly persons with somatic health problems maintain control and balance in life and optimize well-being. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 6(1). doi: 10.3402/qhw.v6i1.6030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. K., Holahan C. J., Velasquez K. E., North R. J. (2008). Longitudinal change in happiness during aging: The predictive role of positive expectancies. The International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 66, 229-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released. (2013). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 22.0). Armonk, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen S. L., Stube J. E. (2014). Older adults’ perceptions of physical activity: A qualitative study. Occupational Therapy International, 21, 53-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. H. (2009). Older people’s expectations regarding ageing, health-promoting behaviour and health status. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 84-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B. R., Myers L. M. (2004). Preventive health behaviors influenced by self-perceptions of aging. Preventive Medicine, 39, 625-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B. R., Slade M. D., Kunkel S. R., Kasl S. V. (2002). Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 261-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisner B. A., Baker J. (2013). An exploratory analysis of aging expectations and health care behavior among aging adults. Psychology and Aging, 28, 99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisner B. A., Weir P. L., Baker J. (2013). The relationship between aging expectations and various modes of physical activity among aging adults. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14, 569-576. [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. C. (1993). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology, 43, 2412-2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien Cousins S. (2000). “My heart couldn’t take it”: Older women’s beliefs about exercise benefits and risks. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 55, P283-P294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien Cousins S. (2003). Grounding theory in self-referent thinking: Conceptualizing motivation for older adult physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4, 81-100. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Hayes A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prohaska T. R., Keller M. L., Leventhal E. A., Leventhal H. (1987). Impact of symptoms and aging attribution on emotions and coping. Health Psychology, 6, 495-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W., Hickey T. (1992). Mortality and the attribution of health problems to aging among older adults. American Journal of Public Health, 82, 1139-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B., Palmer M. H., Jenkins L. S., Spellbring A. M. (2000). Path analysis of efficacy expectations and exercise behaviour in older adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31, 1309-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian C. A., Hays R. D., Berry S., Mangione C. M. (2002). Development, reliability, and validity of the Expectations Regarding Aging (ERA-38) Survey. The Gerontologist, 42, 534-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian C. A., Hays R. D., Mangione C. M. (2002). Do older adults expect to age successfully? The association between expectations regarding aging and beliefs regarding healthcare seeking among older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50, 1837-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian C. A., Liu H., Ensrud K. E., Stone K. L., Mangione C. M. Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. (2001). Correlates of attributing new disability to old age. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 49, 134-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian C. A., Prohaska T. R., Davis C., Weiner B. (2007). Pilot test of an attribution retraining intervention to raise walking levels in sedentary older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55, 1842-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian C. A., Prohaska T. R., Wong M. D., Hirsch S., Mangione C. M. (2005). The relationship between expectations for aging and physical activity among older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 911-915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers D. M., Bolender B. C., Crocker A. B. (2010). Beliefs about aging: Implications for future educational programming. Educational Gerontology, 36, 1022-1042. [Google Scholar]

- Vander Zee K. I., Sanderman R., Heyink J. W., de Haes H. (1996). Psychometric qualities of the RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0: A multidimensional measure of general health status. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 3, 104-122. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0302_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S. N., Sechrist K. R., Pender N. J. (1995). The health promoting lifestyle profile II. College of Nursing, Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Medical Center. [Google Scholar]

- Walker S. N., Hill-Polerecky D. M. (1996). Psychometric evaluation of the health-promoting lifestyle profile II. In Proceedings of the 1996 Scientific Session of the American Nurse Association’s Council of Nurse Researchers (110 pp.). Washington, DC: American Nurses Association. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D. E., Nicol C. W., Bredin S. S. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174, 801-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen C. P., Wai J. P. M., Tsai M. K., Yang Y. C., Cheng T. Y. D., Lee M. C., . . . Wu X. (2011). Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 378, 1244-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage J. A., Brink T. L., Rose T. L., Lum O., Huang V., Adey M., Leirer V. O. (1983). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 37-49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]