Abstract

Objectives:

This article focuses on the results of evaluations of two business plans developed in response to a policy initiative which aimed to achieve greater integration between primary and secondary health providers in New Zealand. We employ the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to inform our analysis. The Better, Sooner, More Convenient policy programme involved the development of business plans and, within each business plan, a range of areas of focus and associated work-streams.

Methods:

The evaluations employed a mixed method multi-level case study design, involving qualitative face-to-face interviews with front-line staff, clinicians and management in two districts, one in the North Island and the other in the South Island, and an analysis of routine data tracked ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations and emergency department presentations. Two postal surveys were conducted, one focussing on the patient care experiences of integration and care co-ordination and the second focussing on the perspectives of health professionals in primary and secondary settings in both districts.

Results:

Both evaluations revealed non-significant changes in ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations and emergency department presentation rates and slow uneven progress with areas of focus and their associated work-streams. Our evaluations revealed a range of implementation issues, the barriers and facilitators to greater integration of healthcare services and the implications for those who were responsible for putting policy into practice.

Conclusion:

The business plans were shown to be overly ambitious and compromised by the size and scope of the business plans; dysfunctional governance arrangements and associated accountability issues; organisational inability to implement change quickly with appropriate and timely funding support; an absence of organisational structural change allowing parity with the policy objectives; barriers that were encountered because of inadequate attention to organisational culture; competing additional areas of focus within the same timeframe; and consequent overloading of front-line staff which led to workload stress, fatigue and disillusionment. Where success was achieved, this largely hinged on the enthusiasm of a small pool of front-line workers and their initial buy-into the idea of integrated care.

Keywords: Evaluation, integration, healthcare reform

Introduction

As with other advanced capitalist societies, New Zealand (NZ) faces a range of policy challenges over health system performance and sustainability. Primary healthcare reform has been prescribed as a potential panacea for those who have historically invested disproportionately in hospital-based services and technology.1 The need for reform has also been precipitated by constrained health budgets, ageing populations and the increasing and costly burden of chronic care on health systems.1–4

From 2008 on, the NZ government through the Ministry of Health focused on achieving Better, Sooner, More Convenient (BSMC) health services, this policy emphasised integration of care and the need for greater efficiency and cost reduction (http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/better-sooner-more-convenient-health-care-community). The Minister of Health called for proposals nationally, of which nine proposals were selected and invited to submit a detailed plan (business plans). Thus, in primary health care, the BSMC policy was operationalised through nine business plans which were developed and implemented through new ‘alliances’. The alliances included representatives from the primary care health organisation and the secondary care providers (district health boards (DHBs) and hospitals). Each business plan involved the introduction of a range of areas of focus and associated work-streams aiming to facilitate horizontal integration across primary health care and vertical integration between primary health care and secondary care. The overall objective was keeping people well, achieving greater efficiency and reducing demand on expensive hospital services.

This article draws on our process and outcomes evaluation of the implementation of two of these business plans, one in the North Island and involving one primary health organisation (PHO) and DHB and the other in the South Island, also involving one PHO and DHB. In both cases, the business plans were addressing health care in a specific geographic district. We employ the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)5 to inform our analysis of the content of the business plan (and specific work-streams) and the implementation process. The evaluation also addressed quantitatively the impact of the business cases through an analysis of routinely collected data and patient and staff surveys. The latter is addressed in a forthcoming publication. This article also makes a number of recommendations about implementation of business plans that aim to bring about transformative change to a health system in an advanced capitalist society context.

Research literature

The international literature suggests that primary healthcare-oriented health systems are more effective, equitable and efficient.6 However, realising this orientation involves a range of complex changes to structure, processes and organisational and community cultures. Starfield7 identified four pillars of primary health care: (1) first contact care; (2) continuity of care over time; (3) comprehensiveness, or concern for the entire patient rather than one organ system; and (4) co-ordination with other parts of the health system. In addition, an integrated system places primary health care at its centre and should include computerisation of information; care that is measured regularly to ensure high quality; practice systems that focus attention on chronic and preventive care; concern for the entire population of patients; and a patient-centred culture that places patient need before anything else.8

The literature reveals a range of challenges common to the operationalisation of integrated care.9 These challenges include workforce shortages; increased workloads; inefficient work environments; increases in unrewarding administrative tasks; concerns over the quality of physician–patient interactions and achieving timely access to care for all.10 To date, operationalisation has tended to involve creating or reconfiguring primary health care in the community where in the United States for example, ‘patient-centred medical homes’6 are a key entity providing primary care. In NZ, ‘the integrated family health centre’ (IFHC) has been embraced and by placing primary care at the centre the intention has been to dissolve the division between primary care and secondary care and ultimately reduce the costs associated with the provision of secondary care in hospital settings.

Furthermore, the research literature stresses that for transformative change of this kind to be realised, there are five critical ‘human’ factors: (1) Impetus to transform; (2) Leadership commitment to quality; (3) Improvement initiatives that actively engage staff in meaningful problem solving; (4) Alignment to achieve consistency of organisation-wide goals with resource allocation and actions at all levels of the organisation and (5) Integration to bridge traditional intra-organisational boundaries between individual components (‘silos’).11 It has been suggested that ‘transformative change’ takes time, most likely over a decade, and is possibly better conceptualised as ‘a continuing journey with no fixed endpoint’11(p. 319). However, the timeframe for policy development and operationalising change in democratic countries tends to be short and shaped by electoral cycles and annual budgets. These different contextual factors present real challenges to those involved in managing change within healthcare systems.8

NZ healthcare context

The health system in NZ is predominantly publicly funded. Many services are free of charge for patients although most patients pay a user charge to access primary healthcare services.

A central Ministry of Health is responsible for policy development and oversight. In all, 20 DHBs plan, fund and deliver hospital services, and fund primary healthcare services, in their respective geographical areas. The governance of the DHBs is by boards of elected and appointed members who are accountable to the Minister of Health.

Since 2002, primary health care has been co-ordinated and managed through private not-for-profit PHOs, which receive capitation funding for their enrolled populations.12 PHOs, in turn, have contracts with a range of primary healthcare service providers.

Policy context and theory behind the business plans: BSMC

All of the business plans put forward by the various ‘alliances’ responded to the BSMC objectives of establishing IFHCs with multi-disciplinary healthcare teams, realising the need to be cost-effective while ensuring quality and safe care for patients.

In both business plans evaluated, an alliance contracting approach was adopted. Alliance contracting is taken from industry and was developed to stimulate collaborative relations, shared decision-making and to improve performance. Key to this approach is the notion that efficiencies can be gained by encouraging a reflective culture and one that operates on the basis of mutual trust and resource sharing.13

There were three areas of focus common to most business plans and health alliances: (1) long term conditions (chronic care management); (2) information management systems (shared care records) and (3) older people. Central to these areas of focus was the objective of realising integrated and co-ordinated care across the different systems of care; improved patient experience; efficiencies and cost reductions gained through reduced emergency department (ED) admissions and ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations (ASHs) and greater co-ordination of service delivery.

Long-term conditions

An ageing population, longer life expectancy, increasing numbers of people with chronic conditions and the burden for health services are all issues that the BSMC Primary Health Care Initiative sought to address. Providing integrated care is particularly testing when providing health services for those with multiple, complex chronic conditions in an environment where there is a need to address efficiency and costs and greater co-ordination of efforts.1,14

Self-management approaches are increasingly used to address the needs of those with long-term health conditions15 and are seen as a means of bridging the gap between patient need and health system capacity. A number of BSMC business plans addressed long-term conditions with many employing Wagner’s16 Chronic Care Model and the Continuum of Care Approach. There is some evidence that this model and approach, where services are integrated, can improve health outcomes.13

Quality and efficiency through health information technology

Information technologies are widely considered a means to address patient safety, quality of care, and efficiency of healthcare service delivery and healthcare integration.14 Personal shared electronic health records have been embraced as one means to realise the new care model. Here, technology facilitates information exchange and provides a mechanism for engagement with self-management while supporting continuity of care.15,17

To date, policy development and implementation in this field in NZ have been problematic, with issues surrounding overlapping databases, data collection inconsistencies, a lack of co-ordination across the sector and incompatible systems that are not always conducive to realising the efficiencies that these technologies potentially offer.18,19

Older people

Frail elderly people, who suffer from functional decline and comorbidity, require effective integrated intervention. Internationally, this has involved providing team delivery of care and patient and family engagement.20 Research demonstrates that integrated health delivery for older people is often suboptimal.21 In NZ, the evidence suggests a need to integrate primary, community and hospital/specialist and residential care services, and provide multi-disciplinary assessment and case management.

The two business plans

The business plans were implemented between 2010 and 2013 and the evaluation research was conducted between February 2013 and February 2014. The focus on two business plans was to generate comparative insight into implementation and outcomes in two geographical districts, one in the North Island and the other in the South Island. The two districts share commonalities with respect to age, ethnicity and socio-economic variances; however, the South Island district is more sparsely populated, contains greater rural remoteness and has a greater level of socio-economic deprivation. In addition, the South Island district has experienced significant staff recruitment and retention issues. Nonetheless, both business plans were attempting to facilitate greater integration and co-ordinated care within primary health care and between primary and secondary health care. Ultimately, the aims were to improve both the patient journey, health outcomes and provide safe, quality and cost-effective care for diverse populations.

The aim of our research was to evaluate whether the business case and objectives led to the realisation of integrated and co-ordinated care across the different systems of care; improved patient experience; greater co-ordination of service delivery; and whether efficiencies and cost reductions had been gained through reduced ED admissions and ASHs.

Methods

We employed a mixed method, multi-level case study design,22 with qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. The two case studies focussed on two alliances, one in the North Island and one in the South. The selection of these cases was informed by the commonality of demographic profiles of the geographic areas and the areas of focus, and the differences between these cases, specifically rural remoteness and socio-economic deprivation for the Southern case. We were interested to know whether rural remoteness and greater socio-economic deprivation would impact on implementation. The qualitative method allowed us to explore inductively the implementation process and to generate an in-depth understanding of how this process was experienced by a range of health professionals. We conducted face-to-face semi-structured interviews with clinicians, allied health professionals, managers and front-line staff working in the community, and non-government organisations (NGOs) at both case sites. The interviews took 60–120 min. Participant selection was determined by their involvement in the development of the business plan, role in the formation of the alliance and involvement in the three areas of focus chosen for the evaluation, that is, long-term conditions; health information technology and older people. The planned focus on the three areas of focus was challenged, however, by the complexities and evolution of proposed areas of focus and the inconsistent and variable roll out of some work-streams over the implementation timeframe. In recognition of this, the research partners in both the North and South Islands provided a wider range of contacts who could provide insight into the dynamics driving this evolution.

The semi-structured interview schedule had four main areas: the role of the participant, understanding of BSMC and the business plan and work-streams, and what had happened in practice. Participants were invited to reflect on what had worked well and what had not worked so well. We employed a dialogic interviewing method which allows the participant to direct the narrative and enables exploration of issues and concerns that are important to the participant and relevant to their experience and role. All of the interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Saturation determined the sample size and in both locations saturation was reached with 24 interviewees, giving a total of 48 interviews and more than 80 h of recordings. The transcripts were read and re-read, themes identified and then subject to an interpretative analysis with reference to the key components of the CFIR framework.5

To establish the impact of the business plan and specifically to understand whether the aim of reducing ASH and ED presentations had been realised, we used R software to conduct an analysis of routinely collected data which tracked ASH and ED over the implementation period (2008–2013). Two postal surveys were conducted, one focussing on the patient care experiences of integration and care co-ordination and the second focussing on the perspectives of health professionals, in primary and secondary care settings in both case sites. The patient care survey employed the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC)23 and the health professionals survey used in the Modified Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (MPACIC)24 and adapted questions from the Diabetes Care and Co-ordination Survey25 that had been conducted in the United States, but had not been validated in NZ. The survey distribution was facilitated using enrolled patient lists and staffing lists. The health professionals survey (n = 102) and the patient experience survey (n = 431) were analysed using R software.

Ethics approval was granted by Victoria University of Wellington and the University of Otago human ethics committees. Participants were provided with an information sheet and were able to decline participation.

Theorising complex interventions

There are a range of theoretical models employed to explain how complex interventions in healthcare settings are introduced, embedded and sustained.5 Of particular utility for this study is the CFIR.5 We have used the CFIR to inform our analysis.

The CFIR comprises five major domains: the intervention, inner and outer settings, the individuals involved, and the process by which the implementation will be accomplished. Interaction between these domains ultimately shapes implementation outcomes.5 Key is the stress placed on the importance of understanding ‘context’, where ‘context’ is the setting within which the implementation takes place; the theories underpinning the initiative and its implementation; and wider environmental factors that shape and constrain implementation. Context is dynamic, subject to continual change and involves a range of interactive variables. With complex, multi-faceted initiatives, the fit between the initiative and the context is crucial. Within the CFIR framework, initiatives can be conceptualised as having ‘inner or core components’ which are essential and the key constructs related to the inner setting are as follows: culture (normative values and established practices); the implementation climate (capacity, receptivity, perceptions of the need for change); compatibility (fit with individuals, organisational culture, work flows and systems, or what might be termed ‘human factors’;7 leadership engagement (commitment, involvement and accountability); the structural features of the organisation; the nature of social networks; resourcing; and access to knowledge and information (including computerised information systems). In addition, there are elements that are conceptualised as being more peripheral and subject to modification as implementation takes place. These elements comprise the ‘outer setting’ and include the following: understandings of patient needs and resources; the extent of networking with organisations external to the organisation; and the nature of social capital (where social capital is the quality and extent of these relationships, the extent of shared vision and information sharing and ability to realise change); external mandates and incentives, and the role played by peer pressure. Finally, there are four key activities central to process: planning; engaging (opinion leaders, champions, and change agents); executing; and reflecting and evaluating.5

Findings

The business plans

Central to the BSMC initiative is the notion of ‘integrated care’. With respect to the CFIR framework, this outer setting context (external mandate) erroneously assumed compatibility with respect to the extent of shared vision, information sharing and ability to implement change. In addition, the limited financial support connected to this mandate compromised the ability to implement change.

Context

The CFIR framework stresses that the fit between the initiative and context is vital if transformative initiatives are to be realised and to become the new norm. The lack of fit with the inner core components, specifically pre-existing norms and the historic and continuing cultural and structural realities between primary and secondary care providers and organisations, ensured that realising the set targets was compromised. Insufficient consideration was given to embedding mechanisms that would facilitate changing a culture that was siloed. There was also insufficient social capital between siloed domains. At the heart of this was the historical dominance of DHBs in relation to planning and funding and resource allocation. While this is an outer setting element which is amenable to change, insufficient change took place over the implementation period. For example, in some cases, areas of focus and work-streams were not operationalised because of inadequate resourcing or resource sharing and the absence of a system that would facilitate this.

In both districts, management and front-line staff agreed that the business plans were overly ambitious and that the development of future areas of focus and work-streams should be more focussed and sensitive to local realities. The workplace demands placed on front-line staff were such that they impacted on staff morale and retention. There were significant issues connected to the inner core elements of capacity, receptivity and the perceived need for change, and insufficient match between individuals, existing organisational culture and work flows and systems. Where there were successes, there was an over-reliance on the dedication of key individuals and where these individuals left the organisation the work-streams lost momentum and were compromised. Indeed, it is well documented that many quality improvement initiatives count on the healthcare workforce to implement the changes, without exploring whether the workforce is already working to capacity. Furthermore, it is known that an increase in workload without additional resourcing can lead to a ‘lack of buy-in’, resistance to change, cynicism, burnout and turnover among front-line staff.19

The areas of focus and associated work-streams did provide a platform for staff to consider the value of integration and changes to the service delivery model. Participants agreed that the critical component of integration was improved communication and the development of relationships within and between the respective organisations and that this does not happen quickly. Thus, the timeframe for implementation was too constrained and shifts in communication networks and the development of and recognition of social capital occurs over a longer timeframe, arguably at least a decade.

The business plans envisaged health IT in the form of the shared care record and while this failed to eventuate within the prescribed timeframe there were examples of successful IT implementations such as video consultations. There was a clear consensus in both districts that IT was central to facilitating greater integration. Nonetheless, IT interoperability was not realised and was a significant factor in workload duplication, health workforce frustration and compromised efficiency.

Participants also thought that the various areas of focus and work-streams were at times inadequately resourced and overseen and during the implementation period there was insufficient evaluation of progress for some work-streams. This, in conjunction with problems with governance, meant, in both districts, that some areas of focus and work-streams were only instituted partially or not at all. The ‘Alliance Model’ of governance was predicated on notions of co-operation, trust and equitable use of resources with a view to eroding existing institutional silos and ultimately providing better health outcomes for both individuals and their communities. Despite laudable intentions, and the dedication of many staff, the ‘Alliance Model’ in both cases largely failed to achieve these goals, because in part, members of the Alliance Teams did not trust one another and failed to reach agreement over the distribution of resources, while decisions made at the Alliance level were continually re-litigated and decisions disregarded by senior management at the secondary care level. This, in turn, led to cynicism among front-line staff and disengagement of clinicians from the alliancing process. Ultimately, the Alliance Teams were dysfunctional, failed to make decisions and implement change and succumbed to internal politics and institutional inertia.

Thus, inner core issues of the implementation climate and outer core issues connected to leadership and the ability to execute, reflect and evaluate change were weak. In terms of leadership engagement, there was evidence of commitment but at times conflict within the governance groups ensured decisions were not made, oversight was compromised and accountability was not always evident.

Individuals, the implementation climate and workplace culture

The business plans did not explore potential barriers arising from pre-existing workplace cultures and how the imposition of a broad range of new work-streams was likely to be embraced. In both cases, some areas of focus were derailed because of dominant personalities and an environment where many felt it was not possible to challenge the power held by these individuals. In addition, the internal politics subsumed the intentions behind the business plans, and they became less about organisational integration and more about key individuals pursuing their own goals.

Contrary to the intentions of the business plans, it was clear that a ‘big bang’ roll-out of areas of focus and work-streams was unworkable and many of the front-line staff felt that the areas of focus and large number of work-streams detracted from what they considered to be their core business – caring for patients. Furthermore, some staff expressed concern about patient safety because of increased workloads and felt they could be vulnerable to medico-legal issues. As one participant observed,

Better, Sooner, Faster, More Convenient [sic] … it just seemed like more work for less people … it just seemed they were trying to squish more into roles.

Working in an environment that was described as one of ‘endless change’ led to high stress for some staff, widespread disillusionment and cynicism, staff retention issues and resulted in an inability to maintain momentum for some areas of focus and work-streams. The business case implementation occurred alongside a range of other policy shifts driven by the Ministry of Health and many claimed that this contributed to significant change fatigue and perceptions of ‘change for change sake’.

While some of the proposed work-streams were effectively established for both business plans, ultimately participants reflected that the objectives remained aspirational. It was noted that many successes had less to do with the business plans and more to do with work that pre-dated the business plans or work that was developed independently or in parallel. In some instances, because of both the sheer number of work-streams and degree of overlap, some evolved and to a large extent no longer resembled those proposed in the business plans.

Long-term conditions

It was evident at both sites that chronic care management work-streams were in place prior to the implementation of the business plans. In the North Island district, the Comprehensive Health Assessment (CHA) was a tool which proved to be challenging in terms of development and roll-out. Initially, the CHA instrument was considered too long, inflexible and burdensome to be implemented by front-line staff. Subsequently, the CHA was shortened and an electronic version developed. The software implementation of the CHA was flawed and the technical elements associated with this caused some dissatisfaction with some general practices choosing not to participate and considerable frustration for staff:

It takes too long, when I first started to use the CHA, and the doubling up, you know like if you’re in practice you know this is the hardest part, is the systems don’t connect, absolute waste of time, … because [I have to] take the paper version and enter it there …

The subsequent redevelopment of the software made it more flexible and resolved data management and retention issues.

Older people

The South Island business plan addressed the needs of older people and sought to support access and support services that would be timely, flexible and targeted for individual need. This work-stream pre-dated the BSMC and was largely successful and consolidated by the BSMC initiative. At the time of evaluation, the team of health professionals comprised a dedicated team who had all received up-skilling education opportunities under the BSMC. There was an evident shift from care for the elderly in residential homes towards care in the community. In the North Island case, the services were seen as largely separate prior to the BSMC business plan, but following the BSMC there was a perception that this had changed and that more integrated care was being provided. There was an evident trend towards providing services for the elderly in their own homes. Again, this was largely realised through the efforts of a dedicated multi-disciplinary team. In addition, a more holistic approach was being taken towards health and end-of-life care and this was general practice funded and led by a general practitioner.

Health information technology

Information and communication technologies were proposed as a platform for enhancing integration and as a means of addressing patient safety, quality of care, greater efficiency and better use of resources. However, for both business plans, there were significant challenges and the Shared Care Record area of focus outlined in the business plans were not achieved during the proposed timeframe and currently still face significant challenges. The non-realisation of this objective had implications for many front-line staff. In both case sites, systems were not interoperable and this resulted in inefficiencies, primarily duplication of work, where field staff recorded health data with pen and paper and then were subsequently required to input this data electronically once back in the office at the end of the working day.

Integrated family health centres

Both business plans proposed the establishment of IFHCs. This was not realised in the South Island case. The non-realisation was perceived to hinge on existing buildings being inadequate and space problems were a significant challenge, which at times compromised patient privacy. Funding for the new building was secured after the business plan period. It was noted by some that the new building itself would not constitute the realisation of an IFHC.

In the North Island case, there were two IFHCs. One was housed in a single building which contained the proposed staff mix. However, during the business plan period professional silos remained and the presence of various health professionals did not result in ‘integration’ or cohesive collaboration. As one participant observed co-location does not constitute integration. The other IFHC comprised more than one building and attempts to integrate care pre-dated the business plan. The concept of integration was defined differently in this locale and greater physical distance between primary and secondary care services prompted the establishment of a ‘virtual’ IFHC based on high-speed data transfer between sites and shared electronic records. Again, the implementation of this initiative pre-dated the business plan and was self-funded. There was also apparent willingness of health professionals to collaborate.

Quantitative results

Survey of health professionals and survey of patients with chronic conditions

One of the primary aims of these surveys was to compare perceptions of care from the perspectives of both healthcare professionals and patients. The patient respondents were evenly split between genders, with a median age of 71 years (range: 31–97). Significantly, 32% of the health professionals surveyed were not certain what the BSMC business plan involved or represented.

The most striking thing about the survey data was the major disjunction between patient perceptions and provider perceptions on care co-ordination and integration. Clinicians tended to rate their adherence to the tenets of care co-ordination highly, while patients tended to rate their experience of co-ordinated care less highly. An analysis of the ‘none of the time’ columns in both surveys showed a very significant difference in perception, for example, for the question: ‘How often have you been given a choice about treatment options?’, 25% of patients endorsed ‘none of the time’. For the equivalent staff question, ‘When caring for a patient with a chronic illness, how often do you give them a choice to think about regarding their care or treatment options?’, 0% of staff reported ‘none of the time’. This pattern was repeated across numerous questions. Patients’ rating of quality of care, however, was high with 86% of respondents rating their care as ‘good’ (17%), ‘very good’ (29%) or ‘excellent’ (40%). These responses raise questions about why there are such differences in perceptions of care provision and also challenges assumptions about what constitutes quality of care implicit in the measures used. These results parallel those found by Carryer et al.24 in New Zealand.

Analysis of longitudinal routine data

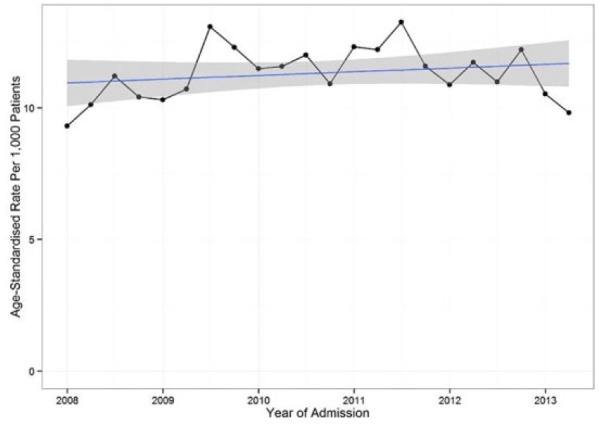

The analysis of routine data revealed that some of the ‘aspirational goals’ outlined in the business case for North Island district, such as a 30% reduction in ASH, were not realised. The North Island business case also aimed to reduce ASH admissions for over 65-year-olds by 20%, but there was no evident trend in the routine data examined and analysed.

Figure 1 illustrates that for all practices in the North Island district, during this period there was no evidence of a decrease in ASH hospitalisations. This includes practices that had not implemented the CCM. The South Island district outcomes were largely comparable.

Figure 1.

Ambulatory sensitive hospital admissions, North Island.

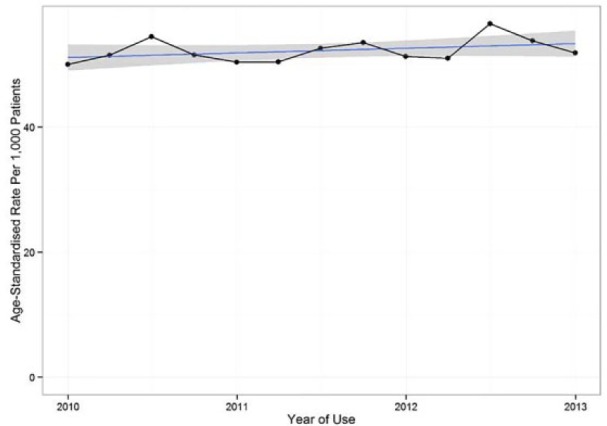

In common with the ASH data, the data for the ED presentations for all PHO practices demonstrate either a flat or slightly upward trend post-implementation of the business case in the North Island district (Figure 2). The South Island district outcomes were largely comparable.

Figure 2.

Emergency department presentations.

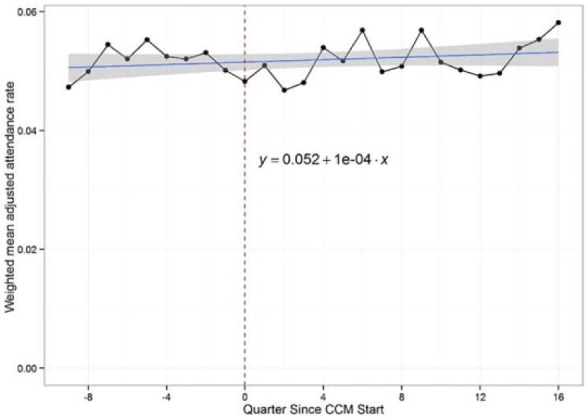

Figure 3 depicts the data for ED presentation rate for patients enrolled in practices that have implemented the CCM programme (adjusted to control for the timing of the CCM implementation). There is no evidence of any change in rate of presentation following the introduction of the CCM.

Figure 3.

Adjusted emergency department trend for North Island District.

The fact, however, that neither ASH admissions nor ED presentation rates declined does not imply the CCM model itself was a ‘failure’. A number of the areas of focus in the business case were intended to contribute to the goals of declining ASH and ED rates. While it is desirable to have lower rates of secondary care use, ASH and ED presentation rates are blunt metrics by which to judge the success, or otherwise, of individual projects. Patients involved in the CCM programme may well be more engaged in their care, have improved health-related quality of life and report an improved patient experience of care as a result of the programme. These ‘softer’, although important, outcomes are not captured in the ASH and ED statistics.

Conclusion

The results of our evaluation suggest that the development of highly detailed and prescriptive business plans, that are expected to be rolled out in a relatively short timeframe, may not be the most effective or efficient use of resources to promote integrated care provision. Ultimately, the business plans became less of a blueprint for the specifics of what to do and more aspirational documents to do something about integrated health service delivery. Greater attention to the contextual realities at the outset would have improved business plan development and enabled a clearer understanding of the key barriers to implementation and the need to embed new mechanisms to facilitate both structural and cultural changes.

The BSMC business plans sought to realise efficiencies and cost reductions through reduced ED admissions and ASHs and greater co-ordination of service delivery. This was an ambitious initiative which was ultimately compromised by the following: the size and scope of the business plans; dysfunctional governance arrangements and organisational ability to effect change quickly with appropriate and timely funding support; an absence of organisational structural change allowing parity with the policy objectives; barriers encountered because of inadequate attention to organisational culture; competing additional health initiatives within the same timeframe; and consequent overloading of front-line staff which led to workload stress, fatigue and disillusionment. Where successful, success largely hinged on the enthusiasm of a small pool of frontline workers (champions) and their initial buy-into the idea of integrated care and a patient-centred approach.

Perceptions of care co-ordination and integration were significantly different between patients and health professionals. In addition, ‘care’ and the meanings associated with ‘care’ were challenged by the business plans and their implementation, where many front-line workers felt that in practice their ability to provide ‘care’ had been compromised.

While most of the aspirations were not reached in the implementation period, the business plans did provide the opportunity to consider integrated care, did provoke discussion about what quality primary health care should involve and a willingness to move towards placing primary health care at the centre. Future policy in this area needs to be more cognisant of the structural and cultural realities of healthcare workplaces. It needs to be more considered in terms of breadth and scope and must set timeframes which move beyond electoral cycles and annual budgets. It must allow healthcare workers who are already working in resource-constrained environments the chance to set and realise aspirational goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants at both case study sites who gave freely or their time and expertise. Thank you also to Associate Professor Sarah Derrett for her input into survey development for this project and acquisition of funding. They would also like to thank Professor Jackie Cumming for her assistance with acquisition of funding.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethics approval was granted by the University of Otago Ethics Committee.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Ministry of Health for funding this research.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

References

- 1. Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care – a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1064–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gauld R. Revolving doors: New Zealand’s health reforms – the continuing saga. Wellington, New Zealand: Institute of Policy Studies and Health Services Research Centre, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Health Committee people with long term conditions: a discussion paper. Wellington, New Zealand: National Health Committee, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Health. Aged care literature review: coordination and integration of services, 2001, http://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/pages/aged-care-literature-review.pdf

- 5. Damschroder L, Aron J, Rosalin D, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidation framework for advancing implementation science (Open access). Implement Sci 2009; 4: 50, http://www.implementationscience.com/content/4/1/50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Starfield B. Politics, primary healthcare and health: was Virchow right? J Epidemiol Community Health 2011; 65(8): 653–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005; 83(3): 457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bodenheimer T, Hoangmai HP. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff 2010; 29(5): 799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carrier M, Gourevitch M, Shah N. Medical homes: translating theory into practice. Med Care 2009; 47: 714–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ginsburgh PB, Maxfield M, O’Malley AS, et al. Making medical homes work: moving from concept to practice (Policy perspective no. 1). Washington, DC: Centre for Studying Health System Change, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lucas C, Van Deusen HS, Cohen AB, et al. Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Manage Rev 2007; 32: 309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cumming J, McDonald J, Barr C, et al. New Zealand: Asia Pacific observatory on health systems and policies and the European observatory on health systems and policies. Health Syst Transit 2014; 4(2), http://www.wpro.who.int/asia_pacific_observatory/hits/series/Nez_Health_Systems_Review.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. Exworthy M. Policy to tackle the social determinants of health: using conceptual models to understand the policy process. Health Policy Plan 2008; 23: 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis P, Love P. Alliance contracting: adding value through relationship development. Eng Construct Architect Manag 2011; 18(5): 444–461. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nolte E, McKee M. (eds). Caring for people with chronic conditions: a health system perspective. Berkshire: Open University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract 1998; 1: 2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rozenblum R, Jang Y, Zimlichman E, et al. A qualitative study of Canada’s experience with the implementation of electronic health information technology. CMAJ 2011; 183(5): E281–E288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin G, Lovelock K, Cumming J, et al. Caring and sharing: implementation issues with an electronic shared healthcare record. In: Proceedings of the primary care research conference, Canberra, AUT, Australia, 23–25 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. MacRae J, Martin G, Lovelock K. An evaluation of the shared care record. Technical report, Compass Health, Wellington, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, et al. A survey of primary care physicians in eleven countries, 2009: perspectives on care, costs, and experiences. Health Aff 2009; 28(6): w1171–w1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O’Neil SS, Lake T, Merril IA, et al. Racial disparities in hospitalizations for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. Am J Prev Med 2010; 38(4): 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yin RK. Designing case studies: identifying your case(s) and establishing the logic of your case study, 2011, http://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/24736_Chapter2.pdf

- 23. Glasgow RE, Wagner E, Schaefer J, et al. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness care (PACIC). Med Care 2005; 43: 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carryer J, Budge C, Hansen C, et al. Providing and receiving self-management support for chronic illness: patients’ and health practitioners’ assessments. J Prim Health Care 2010; 2: 124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Derrett S, Gunter K. Care co-ordination in rural communities: preliminary findings on strategies used at 3 safety net medical home initiative sites (webinar). Center for Health Care Innovation, Qualis Health and MacColl, 2012, http://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/Webinar-Care-Coordination-Rural-Communities.pdf [Google Scholar]