Abstract

Background

A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in women with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma to evaluate the efficacy and safety of motolimod—a Toll-like receptor 8 (TLR8) agonist that stimulates robust innate immune responses—combined with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD), a chemotherapeutic that induces immunogenic cell death.

Patients and methods

Women with ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinoma were randomized 1 : 1 to receive PLD in combination with blinded motolimod or placebo. Randomization was stratified by platinum-free interval (≤6 versus >6–12 months) and Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) performance status (0 versus 1). Treatment cycles were repeated every 28 days until disease progression.

Results

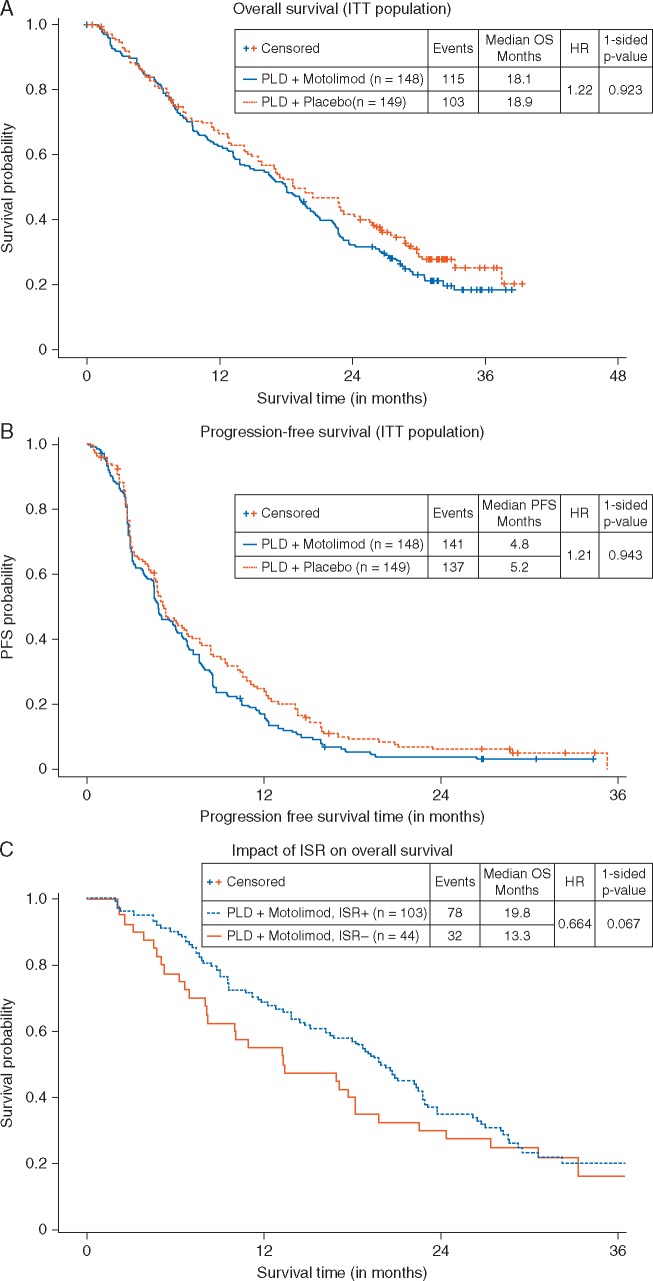

The addition of motolimod to PLD did not significantly improve overall survival (OS; log rank one-sided P = 0.923, HR = 1.22) or progression-free survival (PFS; log rank one-sided P = 0.943, HR = 1.21). The combination was well tolerated, with no synergistic or unexpected serious toxicity. Most patients experienced adverse events of fatigue, anemia, nausea, decreased white blood cells, and constipation. In pre-specified subgroup analyses, motolimod-treated patients who experienced injection site reactions (ISR) had a lower risk of death compared with those who did not experience ISR. Additionally, pre-treatment in vitro responses of immune biomarkers to TLR8 stimulation predicted OS outcomes in patients receiving motolimod on study. Immune score (tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; TIL), TLR8 single-nucleotide polymorphisms, mutational status in BRCA and other DNA repair genes, and autoantibody biomarkers did not correlate with OS or PFS.

Conclusions

The addition of motolimod to PLD did not improve clinical outcomes compared with placebo. However, subset analyses identified statistically significant differences in the OS of motolimod-treated patients on the basis of ISR and in vitro immune responses. Collectively, these data may provide important clues for identifying patients for treatment with immunomodulatory agents in novel combinations and/or delivery approaches.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT 01666444.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor 8, oncology, ovarian cancer, biomarkers, immunotherapy, motolimod

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States and has the highest mortality rate of all gynecologic cancers [1, 2]. The standard treatment of ovarian carcinoma involves debulking surgery and combination chemotherapy with paclitaxel and either carboplatin or cisplatin [3]. However, despite aggressive frontline treatment, ∼70% of patients will relapse in the first 3 years. Among the accepted options for patients with relapsed disease are pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) and other drugs [4–8] with response rates from 10% to 25%. With a dose schedule and toxicity profile somewhat more favorable, PLD has become a common first option for patients who relapse after platinum-based treatment [9, 10].

Numerous studies show that cell-mediated immune mechanisms play a key role in controlling the natural history of ovarian carcinoma [11, 12]. PLD is an immunomodulatory agent that augments anti-tumor immune responses, in part via killing tumor cells in a manner that enhances uptake of tumor antigens by myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs), promoting antigen processing, cross-priming, and presentation to T cells [13–15]. Despite these immune-activating processes, tumor-infiltrating mDCs may not become activated due to immunosuppressive factors within the local tumor microenvironment (TME) [16]. Agents with the potential to enhance the immunomodulatory effects of PLD are therefore attractive candidates for evaluation in ovarian carcinoma.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) comprise a family of 13 pattern recognition receptors expressed broadly on hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells [17]. TLR8 is localized in endosomal compartments of monocytes and mDC and its activation stimulates the release of inflammatory mediators, including T cell helper 1 (Th1)-polarizing cytokines [18, 19]. Motolimod (previously identified as VTX-2337) is a synthetic, small molecule, selective agonist of TLR8 comprising a 2-aminobenzazepine core [20, 21]. Motolimod stimulates natural killer (NK) cell activity [21], augments antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [18, 22] and induces production of IFN-γ.

Because TLR8 engagement drives the maturation of mDCs and could facilitate the development of innate and adaptive antitumor immune response, it was hypothesized that motolimod would be an optimal partner for PLD. Based on this hypothesis, as well as preclinical and initial clinical data supporting the combination [20], the current phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was initiated to compare the efficacy and safety of motolimod plus PLD versus placebo plus PLD in women with advanced ovarian carcinoma.

Methods

This phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was conducted at 105 study centers in the United States. Patients were randomized in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive PLD 40 mg/m2 i.v. on day 1 of a 28-day cycle plus motolimod 3.0 mg/m2 or placebo given SC on days 3, 10, and 17. Starting with cycle 5, dosing consisted of 40 mg/m2 PLD on day 1 plus 3.0 mg/m2 motolimod or placebo on day 3 of a 28-day cycle. Randomization was stratified by platinum-free interval (PFI) (≤6 months versus >6–12 months) and GOG performance status (0 versus 1). Treatment cycles were repeated every 28 days until progressive disease (PD).

Eligible patients were ≥18 years and had measurable, confirmed epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinoma that was persistent or recurrent despite primary therapy. Recurrence must have occurred <12 months after completing platinum-based first- or second-line therapy. Up to 2 prior cytotoxic regimens were permitted; prior treatment with motolimod, PLD, or any other anthracycline was not allowed.

Disease response was evaluated using magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scans carried out at baseline, week 12, and every 8 weeks thereafter until PD or the patient was put on non-protocol therapy. Tumor responses were assessed by the investigator using the Immune Related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (irRECIST) [23].

Safety assessments included the surveillance and recording of adverse events (AEs) that were graded and classified using the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 4.0 [24].

Details on statistical methods and translational endpoints are provided in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 297 patients were randomized between October 2012 and April 2014. The treatment arms were well-balanced regarding demographics and disease characteristics (see Table 1). Of the 297 randomized patients, 294 received blinded study treatment; 147 received motolimod and 147 received placebo. The median number of treatment doses (12 for motolimod, 13 for placebo) and cycles (5 for both motolimod and placebo) was comparable between the arms. The median number of PLD doses was 5 (range: 1–35) in each arm.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| PLD + placebo | PLD + motolimod | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 149 (%) | N = 149 (%) | N = 297 (%) | |

| Median (range) age, years | 61.6 (29.7–91.1) | 63.5 (39.6–84.8) | 62.7 (29.7–91.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 141 (94.6) | 137 (92.6) | 278 (93.6) |

| Black or African American | 4 (2.7) | 6 (4.1) | 10 (3.4) |

| Asian | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | 6 (2.0) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Not stated | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (2.7) | 3 (2.0) | 7 (2.4) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 143 (96.0) | 145 (98.0) | 288 (97.0) |

| Not stated | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Histologic cell type, n (%) | |||

| Serous adenocarcinoma | 122 (81.9) | 124 (83.8) | 246 (82.8) |

| Adenocarcinoma, unspecified | 10 (6.7) | 11 (7.4) | 21 (7.1) |

| Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 9 (6.0) | 5 (3.4) | 14 (4.7) |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (1.7) |

| Mixed epithelial carcinoma | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (1.7) |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.0) | 4 (1.3) |

| Transitional cell carcinoma | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| GOG performance status, n (%)a | |||

| 0 | 104 (69.8) | 105 (70.9) | 209 (70.4) |

| 1 | 45 (30.2) | 43 (29.1) | 88 (29.6) |

| Primary tumor site, n (%) | |||

| Ovarian | 119 (79.9) | 116 (78.4) | 235 (79.1) |

| Fallopian tube | 12 (8.1) | 13 (8.8) | 25 (8.4) |

| Primary peritoneal | 18 (12.1) | 19 (12.8) | 37 (12.5) |

| Median (range) time from diagnosis to study entry, weeks | 73.1 (16.3, 948.4) | 74.3 (29.3, 787.4) | 73.6 (16.3, 948.4) |

| Prior chemotherapy regimens, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 81 (54.4) | 69 (46.6) | 150 (50.5) |

| 2 | 64 (43.0) | 74 (50.0) | 138 (46.5) |

| 3 | 4 (2.7) | 5 (3.4) | 9 (3.0) |

| Platinum-free interval, n (%)a | |||

| ≤ 6 months | 77 (51.7) | 75 (50.7) | 152 (51.2) |

| > 6 to ≤ 12 months | 72 (48.3) | 73 (49.3) | 145 (48.8) |

As randomized.

OS, irPFS, and ORR

The addition of motolimod to PLD did not improve either OS or progression-free survival as assessed by irRECIST (irPFS). In the intent-to-treat analysis, the median OS for patients in the motolimod plus PLD arm was 18.1 months versus 18.9 months for patients in the placebo plus PLD arm [hazard ratio (HR) 1.22, P = 0.923; Figure 1A]. The median irPFS for patients who received motolimod plus PLD was 4.8 months versus 5.2 months for patients in the placebo plus PLD arm placebo (HR 1.21, P = 0.943; Figure 1B). (All P-values are one-sided log rank.) Motolimod did not improve OS or irPFS in patients with PFI ≤6 months or >6–12 months, nor the objective response rate (see supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots of OS (A) and PFS (B) in the ITT population. No significant increase in either OS or PFS was observed between patients treated with motolimod plus PLD (blue line) and patients treated with placebo plus PLD (red line). Landmark analysis of OS in patients receiving motolimod, comparing those who experienced injection site reaction (ISR+; blue line) to those who did not (ISR−; red line) (C). Among motolimod-treated patients, those who were ISR+ had longer OS compared with those who were ISR−.

OS and ISR

The most common motolimod-associated AE was ISR, which occurred in 108 patients (73.5%). Planned analyses (for statistical methods, see supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online) of the association between OS and ISR suggested that patients in the motolimod arm who experienced ISR (n = 103) had longer OS (19.8 months) compared with motolimod-treated patients who did not experience ISR (n = 44; 13.3 months) (Figure 1C). Using a time-dependent proportional hazards model, the estimated hazard of death for ISR+ patients was 66.4% the hazard of those who were ISR− (P = 0.067).

Safety

Motolimod plus PLD was generally safe and well-tolerated, without evidence of toxicity interactions. Notable treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) that were reported in a higher proportion of patients in the motolimod arm versus placebo (≥10% difference) were fatigue, vomiting, ISR, chills, fever, limb edema, influenza-like symptoms, and cytokine release syndrome (see Table 2). With these exceptions, the incidence of TEAEs did not appear to be different between the treatment arms.

Table 2.

Adverse events

| Patients with adverse events, n (%) | PLD + placebo N = 147 (%) | PLD + motolimod N = 147 (%) | Total N = 294 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any treatment-emergent adverse event | 146 (99.3) | 147 (100.0) | 293 (99.6) |

| Grade ≥3 | 91 (61.9) | 94 (63.9) | 185 (62.9) |

| Grade ≥4 | 14 (9.5) | 10 (6.8) | 24 (8.2) |

| Grade 5 | 6 (4.1) | 7 (4.8) | 13 (4.4) |

| Any serious adverse event | 60 (40.8) | 60 (40.8) | 120 (40.8) |

| Any adverse event leading to treatment discontinuation | 5 (3.4) | 12 (8.2) | 17 (5.8) |

| Treatment-emergent adverse events with ≥5% difference in incidence between arms | |||

| Fatigue | 109 (74.1) | 129 (87.8) | 238 (81.0) |

| Injection site reaction | 13 (8.8) | 108 (73.5) | 121 (41.2) |

| Chills | 25 (17.0) | 93 (63.3) | 118 (40.1) |

| Vomiting | 49 (33.3) | 74 (50.3) | 123 (41.8) |

| Fever | 19 (12.9) | 70 (47.6) | 89 (30.3) |

| Influenza-like symptoms | 8 (5.4) | 45 (30.6) | 53 (18.0) |

| Edema limbs | 19 (12.9) | 37 (25.2) | 56 (19.0) |

| Anxiety | 24 (16.3) | 32 (21.8) | 56 (19.0) |

| Insomnia | 16 (10.9) | 27 (18.4) | 43 (14.6) |

| Weight loss | 19 (12.9) | 25 (17.0) | 44 (15.0) |

| Cytokine release syndrome | 2 (1.4) | 24 (16.3) | 26 (8.8) |

| Dizziness | 14 (9.5) | 24 (16.3) | 38 (12.9) |

| Muscular weakness | 14 (9.5) | 22 (15.0) | 36 (12.2) |

| Dyspepsia | 13 (8.8) | 22 (15.0) | 35 (11.9) |

| Hyperglycemia | 28 (19.0) | 19 (12.9) | 47 (16.0) |

| Skin infection | 6 (4.1) | 16 (10.9) | 22 (7.5) |

| Hypokalemia | 29 (19.7) | 12 (8.2) | 41 (13.9) |

| Ascites | 17 (11.6) | 9 (6.1) | 26 (8.8) |

Serious AEs (SAEs) were reported for 120 patients (40.8%): 60 patients (40.8%) in each treatment arm (see Table 2). Of the SAEs that resulted in death (n = 13; 4.4%), 1 event—sepsis in a patient in the placebo arm—was considered related to study treatment. Most deaths (66%) were reported after completion of treatment and were related to progression of underlying disease (70.4%).

Correlative studies

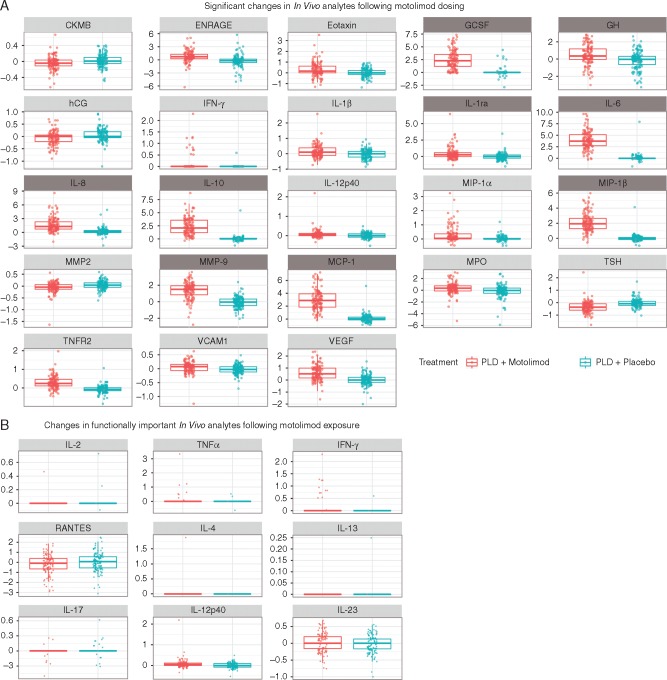

Analysis of previous nonclinical and clinical data identified a panel of cytokines and chemokines induced by motolimod in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro and/or that were upregulated in plasma following subcutaneous dosing (see supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online). In vivo analytes were quantified in plasma samples collected from patients before and 8 h following motolimod dosing. Post-dose levels of responsive mediators in patients treated with motolimod plus PLD showed statistically significant increases consistent with previous findings in human volunteers and cancer patients who received motolimod monotherapy [18, 19] and ovarian cancer patients treated with motolimod plus PLD [20] (Figure 2A and B; supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). In vivo responses were not significantly associated with longer OS or irPFS (data not shown).

Figure 2.

(A) Statistically significant (two-sided P < 0.05) upregulation of plasma analytes following subcutaneous administration of 3.0 mg/m2 of motolimod. Analytes that were prospectively identified as being responsive to TLR8 stimulation by motolimod are identified with a dark gray heading. Data shown represent log-fold changes (pre-dose to 8 h post-dose) in each analyte. P-values for each analyte are provided in supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online. (B) In vivo upregulation of immunologically important analytes. P-values for each analyte are provided in supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online.

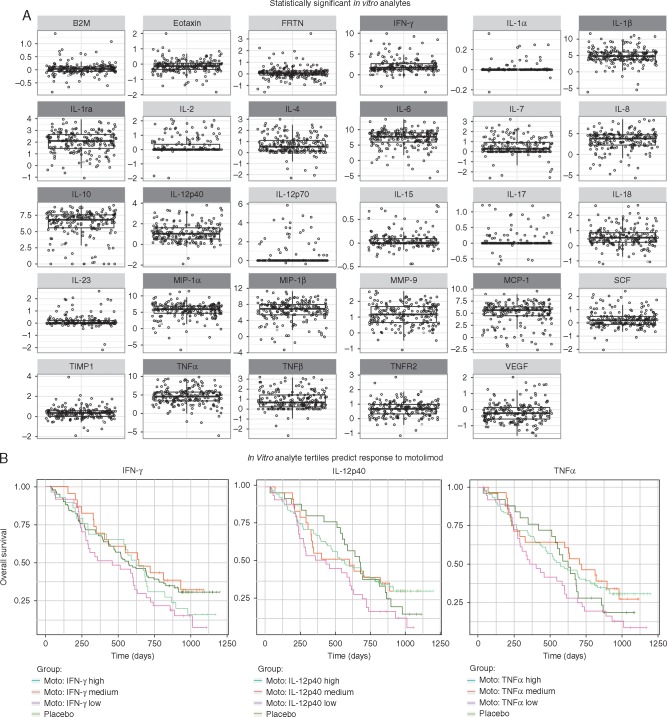

Before initiating study treatment, all patients were assessed for their ability to respond to TLR8 stimulation in vitro. The repertoire and magnitude of mediators that were significantly induced was consistent with prior studies (Figure 3A). For all subjects, in vitro responses in select analytes were discretized into tertiles (low, medium, or high), and used to compare clinical outcomes. Subjects with higher baseline IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-12p40 responses who subsequently received treatment with motolimod plus PLD had significantly longer survival compared with motolimod-treated subjects with low mediator response (Figure 3B). This finding was not duplicated in the PLD plus placebo group. Additionally, exploratory analyses identified in vitro analytes that were correlated with injection-site reactions (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 3.

(A) Statistically significant (two-sided P < 0.05) upregulation of analytes in vitro from baseline (pre-treatment) assessment of immune responsiveness to TLR8 stimulation. Data shown represent log-fold changes in each analyte in response to in vitro stimulation with 300 nM motolimod compared with null (no stimulant). Corresponding P-values are provided in supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online. Analytes that were prospectively identified as being responsive to in vitro activation of TLR8 by motolimod are identified with a dark gray heading. (B) Analysis of OS by baseline in vitro response in IFN-γ (A), IL-12p40 (B), and TNF-α. (C) In vitro responses for each analyte was discretized as low, medium, or high and their association with survival was tested using a one-sided log-rank test. Within the motolimod plus PLD treatment group only, patients with higher IFN-γ (P = 0.049), TNF-α (P = 0.041), or IL-12p40 (P = 0.024) response had significantly improved survival compared to those motolimod-treated subjects who had a lower level of mediator response.

No significant associations were identified between OS or irPFS and immune score (TILs), TLR8 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), germline BRCA–Fanconi anemia mutational status, or autoantibody biomarkers (see supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

In this study of 297 patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, the addition of motolimod to PLD did not produce an improvement in either of the co-primary endpoints of OS or irPFS. In addition, no statistically significant improvement in OS or PFS was observed in any subgroup analyzed, including the subgroups defined by PFI. The combination of motolimod plus PLD was well tolerated and was associated with a safety profile consistent with that seen in previous motolimod studies.

Despite the supportive preclinical data and the confirmation of expected motolimod immunopharmacology, there was a lack of synergy between motolimod and PLD in this study. There is robust evidence that host anti-tumor cell-mediated immune mechanisms play a role in the natural history of ovarian carcinoma [11, 25]. However, the disease has thus far been relatively resistant to treatment with immunotherapy agents, including immune checkpoint blockade [26, 27]. The low response rates to blockade of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) compared with other tumor types may be attributable at least in part to the lower rate of mutations in ovarian cancer relative to cancers such as melanoma or lung cancer [28] and to a more immunosuppressive TME. This incomplete understanding of the immunobiology of ovarian cancer renders clinical trials in unselected patients particularly challenging, and provides a strong impetus for better understanding of the mechanisms of immune suppression in ovarian cancer.

This study may provide important insights regarding immunomodulatory approaches to ovarian cancer. Based on preclinical data [20], our underlying hypothesis was that TLR8 stimulation would activate intratumoral antigen-presenting cells, allowing them to mobilize adaptive immunity against tumors, and also activate intratumoral macrophages to synergistically kill tumor cells in combination with PLD. Motolimod indeed activated innate immunity in this study, as evidenced by the marked increase of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in plasma after dosing including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα, as well as proangiogenic factors such as IL-8, VEGF, and MMP9. These multifaceted biologic effects highlight the complexity of systemic TLR8 activation. The lack of correlation between the pharmacodynamic response to motolimod and clinical outcomes further underscores this issue. The fact that these biomarkers were assessed in vivo at a single, operationally feasible time-point may have inherently limited their utility to predict or correlate with clinical outcomes.

Nevertheless, in contrast to the in vivo pharmacodynamic results, a statistically significant difference was observed in the OS of motolimod-treated patients with high baseline IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-12p40 in vitro responses to motolimod compared with motolimod-treated patients with low baseline analyte responses. These data underscore the heterogeneity of immune responses, and validate the use of pre-treatment in vitro methods for assessing immune fitness and/or the immune response profile before initiation of immunotherapy. We did not observe any correlation of survival or benefit from the combination with BRCA-Fanconi pathway mutation status, which may be explained by the fact that this trial selected for BRCA mutation carrier patients with decreased platinum sensitivity. Furthermore, pre-existing TILs did not predict OS or benefit from the combination in this study. It is possible that the immunomodulatory effects of PLD [13–15] may have converted TIL-negative to TIL-positive tumors post therapy, thereby masking the predictive effects of pre-treatment TILs.

Interestingly, patients who developed inflammatory responses at the site of motolimod injection also had longer survival compared with motolimod-treated patients who did not. It is possible that in these ISR+ patients, motolimod led to beneficial immunomodulation within the TME, resulting in improved survival in response to therapy compared with their ISR- counterparts. ISR may therefore represent a proxy for immune activation within the TME. It is also likely that multiple steps of immune activation, culminating in an integrated and sustained immune response within the TME, are required to achieve clinical benefit following systemic administration of motolimod. As such, intratumoral delivery of TLR8 agonists may be an effective approach to more directly modulate the TME.

Collectively, the data obtained in the current study may provide important clues regarding patient selection for treatment with TLR8 agonists, as well as new insights for modified delivery approaches in this patient population which could be considered for future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

SNP analysis was carried out by the Immunologic Monitoring Laboratory (IML), part of the Tumor Vaccine Group (TVG) at the University of Washington. Eilidh Williamson provided medical writing assistance, under the sponsorship of VentiRx Pharmaceuticals. Robin Dullea, an employee of VentiRx Pharmaceuticals, provided assistance with the manuscript format and figures. The Biopathology Center provided biospecimen distribution. The authors are solely responsible for the content of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by VentiRx Pharmaceuticals, Seattle, WA. No grant number is applicable.

Disclosure

BJM has received income from Adavaxis, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cerulean, Clovis, GlaxoSmithKline, Gradalis, ImmunoGen, Insys, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, Mateon (formerly Oxigene), Merck, Myriad, NuCana, Pfizer, PPD, Roche/Genentech, TESARO, Verastem, and Vermillion, and research support from Amgen, Array Biopharma, Genentech, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, Morphotek Novartis, and TESARO. KSA has received income from ProvistaDx and is a founder of FlexBioTech. RG has received income from VentiRx Pharmaceuticals. KLM, JKB, and RMH are employees of, and have equity ownership in, VentiRx Pharmaceuticals, and each have patents related to motolimod. RM has received income from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Clovis, Endocyte, MedImmune, and Oxigene. RMH has received income from Celgene and Nanostring Technologies. GC has received research funding from Boeringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, and VentiRx Pharmaceuticals and has a patent related to motolimod. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about ovarian cancer? [article on internet] 2016. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (22 September 2016, date last accessed).

- 2. NIH National Cancer Institute. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Ovarian Cancer [database on internet] 2016. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html (9 November 2016, date last accessed).

- 3. Coleman RL, Monk BJ, Sood AK, Herzog TJ.. Latest research and treatment of advanced-stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013; 10: 211–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morgan RJ Jr, Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD. et al. Ovarian cancer, Version 1.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14: 1134–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buda A, Floriani I, Rossi R. et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing single agent paclitaxel vs epidoxorubicin plus paclitaxel in patients with advanced ovarian cancer in early progression after platinum-based chemotherapy: an Italian Collaborative Study from the Mario Negri Institute, Milan, G.O.N.O. (Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest) group and I.O.R. (Istituto Oncologico Romagnolo) group. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 2112–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vergote I, Finkler NJ, Hall JB. et al. Randomized phase III study of canfosfamide in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin alone in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2010; 20: 772–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mutch DG, Orlando M, Goss T. et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 2811–2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. ten Bokkel Huinink W, Gore M, Carmichael J. et al. Topotecan versus paclitaxel for the treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 2183–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monk BJ, Herzog TJ, Kaye SB. et al. Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 3107–3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D. et al. Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3312–3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D. et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sato E, Olson SH, Ahn J. et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 18538–18543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zitvogel L, Kepp O, Senovilla L. et al. Immunogenic tumor cell death for optimal anticancer therapy: the calreticulin exposure pathway. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 3100–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Casares N, Pequignot MO, Tesniere A. et al. Caspase-dependent immunogenicity of doxorubicin-induced tumor cell death. J Exp Med 2005; 202: 1691–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F. et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med 2007; 13: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V.. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12: 253–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kawai T, Akira S.. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lu H, Dietsch GN, Matthews MA. et al. VTX-2337 is a novel TLR8 agonist that activates NK cells and augments ADCC. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dietsch GN, Randall TD, Gottardo R. et al. Late-stage cancer patients remain highly responsive to immune activation by the selective TLR8 agonist motolimod (VTX-2337). Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 5445–5452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Monk BJ, Facciabene A, Brady WE. et al. Integrative development of a TLR8 agonist for ovarian cancer chemo-immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2016; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dietsch GN, Lu H, Yang Y. et al. Coordinated activation of Toll-Like Receptor8 (TLR8) and NLRP3 by the TLR8 agonist, VTX-2337, ignites tumoricidal natural killer cell activity. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0148764.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stephenson RM, Lim CM, Matthews M. et al. TLR8 stimulation enhances cetuximab-mediated natural killer cell lysis of head and neck cancer cells and dendritic cell cross-priming of EGFR-specific CD8+ T cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2013; 62: 1347–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bohnsack OHA, Ludajic K.. Adaptation of the immune related response criteria: irRECIST. Ann Oncol 2014; 25 (suppl 4): iv361–iv372. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. NIH publication # 09–7473. 2009.

- 25. Hwang WT, Adams SF, Tahirovic E. et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating T cells in ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 124: 192–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mittica G, Genta S, Aglietta M, Valabrega G.. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: a new opportunity in the treatment of ovarian cancer? IJMS 2016; 17(7). doi: 10.3390/ijms17071169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Homicsko K, Coukos G.. Targeting programmed cell death 1 in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3987–3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P. et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature 2013; 499: 214–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.