Abstract

Background

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are highly prevalent among persons living with HIV (PLH) within the criminal justice system (CJS). Extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) has not been previously evaluated among CJS-involved PLH with AUDs.

Methods

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted among 100 HIV+ prisoners with AUDs. Participants were randomized 2:1 to receive 6 monthly injections of XR-NTX or placebo starting one week prior to release. Using multiple imputation strategies for data missing completely at random, data were analyzed for the 6-month post-incarceration period. Main outcomes included: time to first heavy drinking day; number of standardized drinks/drinking day; percent of heavy drinking days; pre- to post-incarceration change in average drinks/day; total number of drinking days; and a composite alcohol improvement score comprised of all 5 parameters.

Results

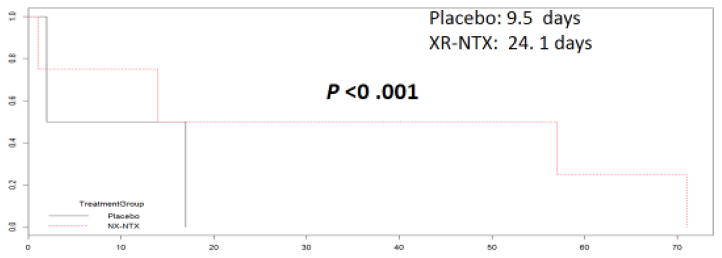

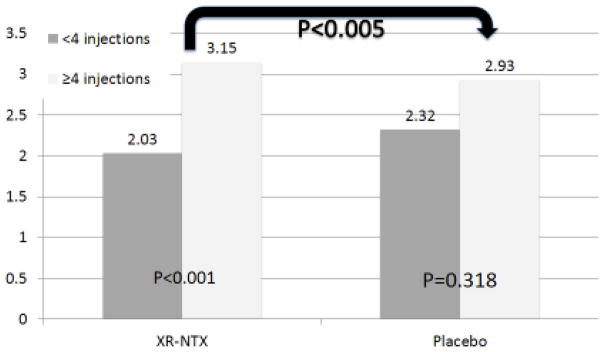

There was no statistically significant difference between treatment arms for time-to-heavy-drinking day. However participants aged 20–29 years who received XR-NTX had a longer time to first heavy drinking day compared to the placebo group (24.1 vs. 9.5 days; p <0.001). There were no statistically significant differences for other individual drinking outcomes. A sub-analysis found participants who received ≥4 XR-NTX were more likely (p<0.005) to have improved composite alcohol scores than the placebo group. Post-hoc power analysis revealed that despite the study being powered for HIV outcomes, sufficient power (.94) was available to distinguish the observed differences.

Conclusions

Among CJS-involved PLH with AUDs transitioning to the community, XR-NTX lengthens the time to heavy drinking day for younger persons; reduces alcohol consumption when using a composite alcohol consumption score; and is not associated with any serious adverse events.

Keywords: Alcohol Use Disorder, Hazardous Drinking, HIV, Extended-Release Naltrexone, prisoners, randomized controlled trial

1.0 Introduction

Globally, the U.S. has the highest incarceration rate with over 700 people incarcerated per 100,000 population (Walmsley, 2014). People living with HIV (PLH) and substance use disorders, especially alcohol use disorders (AUDs), are concentrated in criminal justice settings (CJS). HIV seroprevalence in prisoners is 1.5%, 3-fold greater than among the general U.S. population (Maruschak, 2012), while 40%–60% of prisoners have AUDs, or 8-fold greater than the general population (Mumola, 1999).

In community settings, alcohol use negatively impacts HIV treatment outcomes for PLH (Vagenas et al., 2015; Azar et al., 2010) at all alcohol consumption levels, especially heavy drinking which is associated with HIV medication treatment interruptions (Conen et al., 2013), and increases mortality from direct liver injury or disruptions along the HIV continuum of care including suboptimal antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, ultimately leading to loss of HIV viral suppression (Justice et al., 2016; Palepu et al., 2004; Palepu et al., 2003; Springer et al., 2011a). While studies demonstrate that effectively treating other substance use disorders avoids such outcomes, the impact of treating AUDs on HIV treatment outcomes is unknown.

Naltrexone (NTX), an FDA-approved and evidence-based pharmacotherapy used to treat AUDs, acts as a competitive antagonist at the mu opioid receptor (Anton et al., 2006; Garbutt et al., 2005; Littleton and Zieglgansberger, 2003; O’Malley et al., 2007) and is commercially available in both oral and injectable extended-release (XR-NTX) formulations (Anton et al., 2006; Garbutt et al., 2005). While both preparations effectively lengthen the time to first heavy drinking day among individuals with AUDs in community settings, once-monthly XR-NTX has been proposed to have an adherence advantage over the daily oral formulation (Anton et al., 2006; Kranzler et al., 2008; O’Malley et al., 2007). The extent to which XR-NTX reduces alcohol consumption in PLH, however, is unknown and it is crucial to understand how such pharmacotherapies may improve HIV treatment outcomes.

To date, no randomized controlled trials of XR-NTX have specifically included PLH or prisoners with AUDs. For PLH, particularly those being released from incarceration, XR-NTX has the potential to lengthen the time to first heavy drinking day after release to the community and, therefore, potentially lead to increased stability, linkage to and retention in care, greater ART adherence and long-term HIV viral suppression (Springer et al., 2011a), the ultimate goal of the HIV treatment cascade (Vagenas et al., 2015). It is important to establish whether XR-NTX will have an impact on alcohol relapse in this population and further examine if this has an influence on HIV treatment outcomes given that the U.S. CJS does not routinely provide pharmacotherapies to prevent relapse to AUDs after release to the community (Chandler et al., 2009; Springer et al., 2011b; Taxman et al., 2007).

This current study employs a randomized placebo-controlled design of XR-NTX among incarcerated PLH with AUDs as they transition to the community to evaluate the effect on alcohol consumption post-release with the overall goal of assessing impact on HIV viral suppression. Here, we present results of the alcohol-related analyses.

2.0 Methods

The study protocol and methods have previously been described extensively (Springer et al., 2014), along with preliminary safety (Vagenas et al., 2014) and early post-release retention data (Springer et al., 2015). Briefly, Project INSPIRE is a prospective, double-blinded randomized, placebo-controlled trial of XR-NTX among incarcerated PLH with AUDs who were transitioning to the community from September 2010 and February 2015. The study hypothesis for the parent study is whether XR-NTX effectively reduces alcohol consumption sufficiently to further influence HIV treatment outcomes proximally on the HIV continuum of care including ART adherence and distally as HIV viral suppression (Springer et al, 2014). Therefore, the primary outcome for this study is whether HIV viral suppression rates are higher in PLH treated with XR-NTX compared to placebo at 6 months post-release. In this analysis, we aimed to determine if XR-NTX improved alcohol consumption parameters (our secondary outcomes) among PLH as compared to placebo upon release to the community.

2.1 Recruitment

Recruitment of participants was conducted within the Connecticut Department of Correction (CTDOC) and from a community-based organization that initiates transitional case management 90 days prior to release. Due to uncertainty in release date, PLH either within 90 days of release from CJS or 30 days post-release were screened for hazardous drinking. Screening tools included NIAAA’s single AUD screening question (≥4 drinks daily for women or ≥5 drinks daily for men) (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005) or having met criteria for having an AUD using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor et al., 2001). Individuals who screened positive were further referred for study inclusion and exclusion assessments. Inclusion criteria included: 1) documented HIV-infection; 2) transitioning to greater New Haven or Hartford metropolitan areas in Connecticut; 3) met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) (Amorim et al., 1998; Lecrubier et al., 1997; Sheehan et al., 1997) or hazardous drinking using AUDIT (score ≥4 for women and ≥8 for men) (Barbor, 2001; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005; Saunders et al., 1993); 4) able to provide informed consent; 5) speak English or Spanish; and 6) being ≥18 years. Exclusion criteria included: 1) concurrent prescription of opioid pain medications or expressing a medical indication for them; 2) having grade 3 or higher aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations (>5x upper limit of normal); 3) evidence of Child’s Pugh Class C cirrhosis; 4) enrolled in another pharmacological or ART adherence research study; or 5) breastfeeding, pregnant or unwilling to use contraception for women. Prisoners who were deemed eligible and who expressed interest in the study underwent verbal and written consent. The consent process was repeated after release from prison to prevent real or perceived coercion.

2.2 Ethical Oversight

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Yale University and the CTDOC Research Advisory Committee and registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01077310). This trial involved prisoners with alcohol and substance use disorders, thus additional protections were afforded by the Office of Human Research Protections at the Department of Health and Human Services and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

2.3 Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned receiving, identically packaged, 380 mg of XR-NTX (Vivitrol®) or placebo (provided by Alkermes, Inc), administered intramuscularly every 28 days for six months in a 2:1 ratio of XR-NTX: placebo. XR-NTX patients were oversampled to measure potential adverse side effects. A covariate-adapted randomization was performed using stratified randomization blocks and included the following covariates: city of return (Greater Hartford vs. Greater New Haven) and being prescribed ART.

2.4 Study Measures

Alcohol consumption variables used in this analysis were primarily derived from the Timeline Followback (TLFB) (Sobell and Sobell, 1992, 2000) and assessed self-reported daily totals of standard units of drink 90 days prior to incarceration, the last 30 days of incarceration, and monthly throughout the study period. Alcohol craving was assessed using a monthly-administered 10-point Likert craving scale (0 = “No craving at all” to 10 = “I think about it all the time”).

Other study measures from baseline and monthly interviews included: demographic information (age, gender, race, housing status), health care status, length of incarceration, recidivism information, symptoms of depression using the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Derogatis, 1975), length of lifetime alcohol and drug use, hepatitis C co-infection status, and assessments of mental illness and substance use disorders via the M.I.N.I. version 6 (Sheehan et al., 1997; Sheehan et al., 1998) and the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan et al., 1992; Rikoon et al., 2006). Adverse medication effects were assessed using the Systematic Assessment of Treatment Emergent Effects (SAFTEE) interview (Johnson et al., 2005).

2.5 Variable Definitions

Using the AUDIT, alcohol use disorder severity was stratified using validated cut-offs, including: 1) abstinent or low-risk drinking, defined as a score of 0–3 for women and 0–7 for men; 2) hazardous drinking, as a score of 4–15 for women and 8–15 for men; 3) harmful drinking as a score of 16–19; and 4) possible dependent drinking as a score of ≥20 for men and women (Hall et al., 1993; Saunders et al., 1993). A standard drink was defined as 10 gm of pure alcohol, equivalent to 12 oz. of beer (5% alcohol), 5 oz. of wine (12% alcohol) or 1.5 oz. of distilled spirits (40% alcohol) (Hall et al., 1993; Saunders et al., 1993). Using the TLFB, a drinking day was defined as any day where alcohol was consumed. Heavy drinking days were defined as 5 or more drinks per day for men, or 4 or more drinks per day for women, a definition proven to identify negative consequences associated with drinking to intoxication and used in the COMBINE trial (Anton et al., 2006; Corbin et al., 2014).

In addition to DSM-IV diagnoses of depression and other psychiatric disorders generated by the M.I.N.I., a positive diagnosis for depression using the BSI was defined as a general T-score of ≥63 or any two primary dimension scores of ≥63 (Derogatis, 1975). Active drug use was defined as a positive urine toxicology screen for either opioids or cocaine on the first interview post-release. XR-NTX treatment duration was stratified based on receiving at least 12 weeks of treatment (4 injections or more), based on a systematic review (Bouza et al., 2004) and confirmatory meta-analysis (Roozen et al., 2006) showing that this treatment was associated with better alcohol treatment outcomes.

2.6 Outcome Variables

Though the primary outcome for the parent study involved the proportion achieving HIV-1 RNA viral suppression, the primary outcome for this analysis was related to alcohol consumption, which was assessed both before incarceration and after release using the following outcomes: 1) time to first heavy drinking day post-incarceration, 2) total number of drinks per drinking day; 3) the percent of heavy drinking days; 4) comparison of pre- and post-incarceration change in average drinks per drinking day; and 5) the total number of drinking days.

Recent data suggest that even lower levels of alcohol consumption result in negative adverse clinical consequences in PLH compared to those without HIV (Justice et al., 2016; McGinnis et al., 2016). Therefore, in addition to assessing the above individual alcohol outcomes, in order to assess for a measure of global alcohol consumption, the above variables were equally weighted with a score of “1” for favorable outcomes and combined into a unit-weighted composite score, the ‘composite alcohol score’ in the following manner: 1) the time to first heavy drinking day was considered favorable if the time to first heavy drinking day was greater than the median of the whole group; 2) the total number of drinks per drinking day was considered favorable if the number of drinks per drinking day was below the median of the group; 3) the percent of heavy drinking days was considered favorable if a participant had a percent of heavy drinking days below the median of the group; 4) the pre- to post-incarceration change in average drinks per day was considered favorable if the change was a greater reduction than the median change for the group; and 5) the total number of drinking days was rated favorably if the number of drinking days for the participant was less than the median of the group. This composite alcohol score generated a single summary measure that is more easily amenable to interpretation, and is more sensitive to data variance and subtle changes by reducing floor and ceiling effects. The groups were dichotomized based on the number of injections received at <4 or ≥4 injections.

The TLFB assessment period was censored at 180 days after release; therefore only relapses that occurred within the intervention period were considered in this analysis. Secondary outcomes included incidence of adverse events. Change in mean craving from pre-incarceration to 6-month post incarceration was also assessed.

2.7 Participants

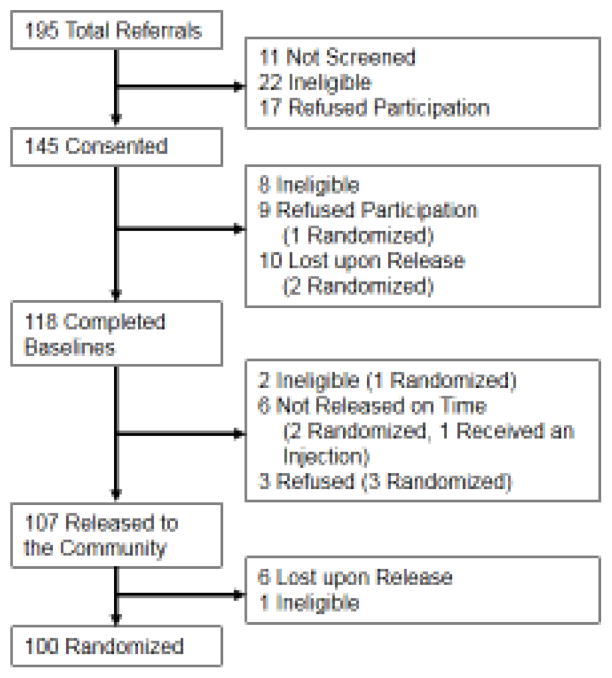

Figure 1 describes the disposition of subjects: 195 PLH were referred to the study, 145 consented to participate, 118 completed baseline assessments and 107 were released to the community. Of these, six participants were lost to follow-up before randomization and 1 was deemed ineligible because of medical need for opioids and were therefore excluded from randomization, leaving 100 in the final analytical sample. The most common reason for not completing enrollment was being released from prison or jail unexpectedly or not completing the initial screening process. Other reasons included: not completing the baseline instruments; not being released during the study period; not meeting criteria for an AUD; not wanting treatment; and having a medical need for prescription opioid medications.

Figure 1.

Enrollment Flow Chart

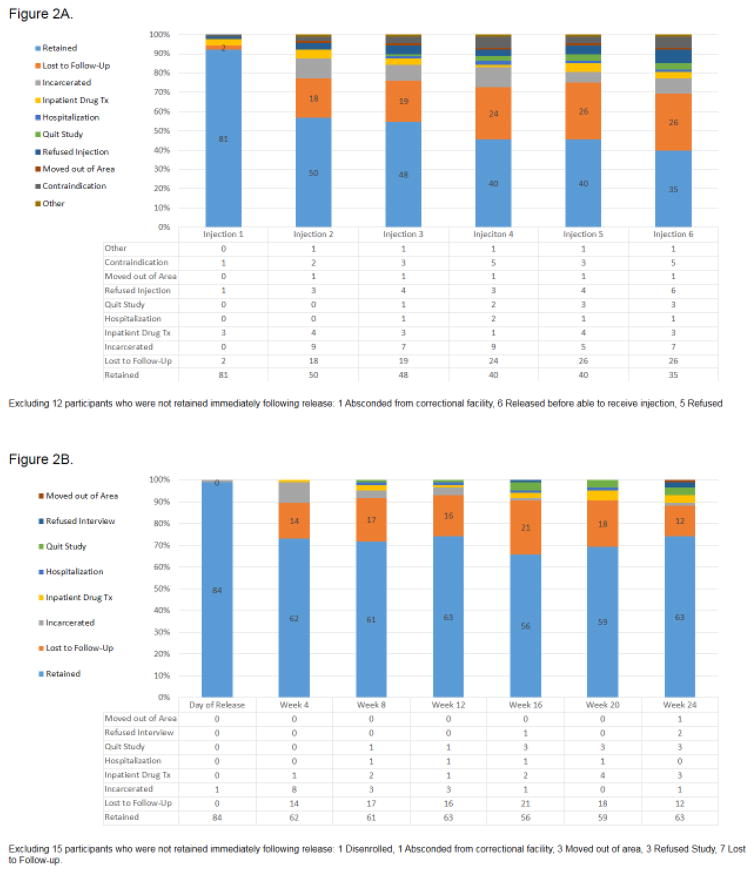

2.8 Participant Attrition

Among the 100 participants included in this analysis, all received baseline interviews, underwent randomization and were released from correctional facilities (prisons and jails); only 7 participants were enrolled post-release. Of these, 15 received no further study visits after release and 12 received no injections at any point of the study. The primary reason for attrition was being released unexpectedly from a correctional facility. Using chi-squared analysis, no statistically significant difference in retention for study visits between study arms was identified; 70.1% of the XR-NTX group returned for 4 or more study visits after release versus 63.6% of the placebo group. Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference between study injection attrition rates and study arms for those who received 4 or more injections (40.3% vs. 45.5%). The XR-NTX group was significantly more likely to adhere to scheduled injections: of 402 scheduled XR-NTX injections over the study period, 202 (50.2%) were administered compared to 88 of 198 (44.4%) scheduled placebo injections (p=0.038). There was an initial drop in retention between the day of release and week 4, after which retention stabilized until the end of the intervention period (week 24). See Figures 2A and 2B for detailed retention data for study injections and visits. Additionally, no statistical difference was found in the rates of recidivism between the two study arms (see Table 1), ensuring a balance in forced abstinence rates among the groups.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. Retention for Study Injections

Figure 2B. Retention for Study Visits

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (N=100)

| Variable | XR-NTX N=67 (%) | Placebo N=33 (%) | Total N=100 (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in Years, Mean (SD) | 44.91 (8.12) | 45.21 (8.92) | 45.01 (8.35) | 0.866 |

|

| ||||

| Age Distribution, years | ||||

| 20–29 | 4 (6.0) | 2 (6.1) | 6 (6.0) | 0.916 |

| 30–39 | 10 (14.9) | 3 (9.1) | 13 (13.0) | |

| 40–49 | 33 (49.3) | 17 (51.5) | 50 (50.0) | |

| 50 and over | 20 (30.0) | 11 (33.3) | 31 (31.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 50 (74.6) | 27 (81.8) | 77 (77.0) | 0.422 |

| Female | 16 (23.9) | 5 (15.2) | 21 (21.0) | |

| Transgender | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.0) | 2 (2.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 46 (68.7) | 19 (57.6) | 65 (65.0) | 0.528 |

| Hispanic | 11 (16.4) | 8 (24.2) | 19 (19.0) | |

| White | 10 (14.9) | 6 (18.2) | 16 (16.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Completed GED or High School (N=99) | 35 (53.0) | 15 (45.5) | 50 (50.5) | 0.568 |

|

| ||||

| Referred from | ||||

| Prison | 17 (25.4) | 6 (18.2) | 23 (23.0) | 0.085 |

| Jail | 43 (64.2) | 27 (81.2) | 70 (70.0) | |

| Community | 7 (10.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Duration of incarceration (months), mean (SD) | 14.0 (30.32) | 11.6 (18.05) | 13.2 (26.82) | 0.683 |

|

| ||||

| Study Site | ||||

| New Haven | 40 (59.7) | 19 (57.6) | 59 (59.0) | 0.839 |

| Hartford | 27 (40.3) | 14 (42.4) | 41 (41.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Housing status (N=99) | ||||

| Stable | 22 (33.3) | 14 (42.4) | 36 (36.4) | 0.440 |

| Unstable | 17 (25.8) | 10 (30.3) | 27 (27.3) | |

| Homeless | 27 (40.9) | 9 (27.3) | 36 (36.4) | |

|

| ||||

| Positive HCV antibody | 29 (47.5) | 16 (50.0) | 45 (48.4) | 0.822 |

|

| ||||

| Currently prescribed ART | 57 (85.1) | 30 (87) | 87 (87) | 0.470 |

|

| ||||

| HIV-RNA viral load (copies/mL) | ||||

| < 400 | 45 (68.2) | 22 (66.7) | 67 (66.7) | 0.799 |

| < 50 | 21 (31.0) | 14 (42.4) | 35 (35.0) | 0.292 |

|

| ||||

| HIV-RNA viral load (copies/mL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4427 (±14386) | 8119 (±37959) | 5683 (±24884) | 0.492 |

| Log10 Mean (SD) | 2.43 1.03) | 2.22 1.04) | 2.36 1.03) | 0.368 |

|

| ||||

| CD4 count ≥200 cells/mL (cells/mL) | 60 (89.6) | 30 (90.9) | 90 (90.0) | 0.832 |

|

| ||||

| Mini International Neuropsychiatric | ||||

| Interview (M.I.N.I.) (N=97) | ||||

| Bipolar Disorder | 12 (18.8) | 4 (12.1) | 16 (16.5) | 0.457 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 10 (15.6) | 4 (12.1) | 14 (14.4) | 0.481 |

| PTSD | 5 (7.8) | 3 (9.1) | 8 (8.2) | 0.536 |

| Panic Disorder | 6 (9.2) | 1 (3.1) | 7 (7.2) | 0.260 |

| Psychotic Disorder | 9 (14.1) | 2 (6.1) | 11 (11.3) | 0.325 |

|

| ||||

| Brief Symptom Index, Depression (N=91) | 46 (78.0) | 22 (68.8) | 68 (74.7) | 0.334 |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol Use Severity (AUDIT criteria) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Abstinent or Low-Risk Drinking | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0.174 |

| Hazardous Drinking | 5 (7.5) | 2 (6.0) | 7 (7.0) | |

| Harmful Drinking | 0 (0.0) | 4 (12.1) | 4 (4.0) | |

| Dependence | 60 (89.6) | 27 (81.8) | 87 (87.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Heavy Drinking (≥5 drinks per day for men, ≥4 drinks for women) | 66 (98.5) | 33 (100.0) | 99 (99.0) | 0.670 |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol craving (scale: 0–10) | 4.08 | 3.44 | 3.83 | 0.443 |

| Mean (SD) | (3.94) | (3.62) | (3.84) | |

|

| ||||

| Opioid Dependence* | 15 (22.4) | 7 (21.2) | 22 (22.0) | 0.894 |

|

| ||||

| Substance use (in years)** | ||||

| Cannabis Mean (SD) | 6.63 (9.55) | 4.14 (7.40) | 5.81 (8.94) | 0.424 |

| Cocaine Mean (SD) | 8.68 (9.94) | 8.34 (10.50) | 8.67 (10.07) | 0.747 |

| Heroin Mean (SD) (N=99) | 3.06 (7.51) | 2.68 (6.76) | 2.94 (7.24) | 0.890 |

|

| ||||

| Substance Use Disorder via M.I.N.I. | ||||

| Cannabis Use Disorder (N=77) | 9 (18.8) | 3 (10.3) | 12 (15.6) | 0.259 |

| Cocaine Use Disorder (N=89) | 38 (63.3) | 15 (51.7) | 53 (59.6) | 0.324 |

| Opioid Use Disorder (N=87) | 11 (19.6) | 3 (9.7) | 14 (16.1) | 0.361 |

|

| ||||

| Injections received | ||||

| 0–3 | 40 (59.7) | 19 (57.6) | 59 (59.0) | 0.839 |

| 4–6 | 27 (40.3) | 14 (42.4) | 41 (41.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Cumulative Injections received | ||||

| 6 | 10 (14.9) | 6 (18.2) | 16 (16.0) | 0.061 |

| 5 | 19 (28.4) | 8 (24.2) | 27 (27.0) | |

| 4 | 27 (40.3) | 14 (42.4) | 41 (41.0) | |

| 3 | 38 (56.7) | 15 (45.5) | 53 (53.0) | |

| 2 | 49 (73.1) | 17 (51.2) | 66 (66.0) | |

| 1 | 61 (91.0) | 24 (72.7) | 85 (85.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Re-incarcerations | ||||

| none | 43 (64) | 23 (70) | 66 (66) | 0.857 |

| 1 | 14 (21) | 6 (18) | 20 (20) | |

| 2 or more | 10 (15) | 4 (12) | 14 (14) | |

Abbreviations: ART= antiretroviral therapy; AUDIT= Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; SD=standard deviation

Using Rapid Opioid Dependence Screen;

Using Addiction Severity Index

3.0 Analytical Approach

Elevated levels of missingness were observed for the longitudinal data; over 40% of participants were missing at least one key independent variable that was central to the analysis. Approximately 25% of the alcohol outcome variables calculated from the TLFB for the 180-day period post-incarceration were missing. Although originally intended to be analyzed using an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach, we evaluated the structure of the missing observations to obtain the most appropriate analyses. We first determined if the data was “Missing Completely at Random” (MCAR), and thus not related to indicators of treatment failure. Determining the structure of the missing data is recommended by Rezvan et al (Hallgren and Witkiewitz, 2013; Rezvan et al., 2015a; Rezvan et al., 2015b) before applying Multiple Imputation (MI). Additionally, new research has shown that MI produces less biased estimates than other methods of handling missing alcohol related-data in a clinical trial (Hallgren and Witkiewitz, 2013). We then followed their reporting requirements for inclusion of MI in medical research. Thus, within the analytic approach and results, we report the level of missingness, the imputation diagnostics, the number of imputations used in the models, and the method of combining the multiple imputed datasets. To further compensate for elevated data missingness, we performed Bayesian simulations - a virtual increase in sample size. We report the results of all three methods of analysis, naïve, imputed and Bayesian to allow the reader to compare the results.

3.1 Missingness Analysis

To determine the structure of the missingness, we assessed whether it was significantly related to the dependent variables or to the independent variables and therefore non-ignorable. The structure of the missing data was assessed using Little’s MCAR (Little, 1988) using code within the BaylorEdPsych package in R (Beaujean, 2012). This test examined the relationship of missingness to all of the variables related to alcohol outcomes used in the analysis. The structure of the missing data based on Little’s MCAR test which was non-significant with a p value >0.56 indicated that the missing data is not statistically related to any of the main outcome metrics used in the analysis (time to first heavy drinking day, total number of drinks per drinking day, percent of heavy drinking days, pre- to post-incarceration change in average drinks per day and total number of drinking days) nor treatment group, thus appropriate for MI. The non-significant finding directly contradicts the standard intent-to-treat assumption that missingness equals failure and indicates that further analysis based on treatment intensity (the number of injections received) be explored. The MCAR missingness structure also allowed us to apply MI which is considered robust under such a structure (Honaker et al., 2011; Rubin, 2008).

3.2 Statistical Models using Multiple Imputation (MI)

Once the MCAR structure of the missingness was determined, we applied MI using the Amelia II package in R software (Honaker et al., 2011). We set the program at the recommended five imputations per dataset that was then combined to a single imputed dataset using Rubin’s rule (Rubin, 2008) that accounts for both the ‘within’ and ‘between’ standard error of the imputed estimates before they are averaged. The Amelia II program assumes that the structure of the missingness is either MCAR or Missing at Random (MAR) and contains a number of algorithms to monitor performance of the MI process.

Of the available metrics, we implemented the “overimputation” and “disperse” functions. Graphical representations that indicated the differences between observed (known) and imputed values were used to assess the performance. We achieved normal Expectation—Maximization (EM) convergence. To assure EM convergence, we used the visual diagnostic “disperse” function from multiple over-dispersed starting values for output from Amelia. For multivariate analysis, we combined five imputed datasets using the Zelig package in R (Choirat et al., 2015; Imai et al., 2008). As noted in the package documentation, Zelig automatically extracts the imputed datasets from the Amelia object, and runs the model in each of them. Estimated model parameters are then summarized, the results from each imputed dataset are available, but more importantly, the combined answer across the imputed datasets calculated by ‘Rubin’s Rules’ (Rubin, 2008) are automatically presented. We also applied the “step” function in R for backward stepwise model selection to determine the most parsimonious model to use. Generalized linear regression models using the imputed data explored relationships for the alcohol improvement score during the study period used the interaction term for two categorical variables in R (treatment arm and the number of injections received).

3.3 Bayesian Modeling

To further explore the relationships suggested by analyses of the imputed dataset for time to first heavy drinking day and average drinks per drinking day (which approached significance with multivariate analysis of imputed data), we created Bayesian Simulations using the arm package in R (version 1.6) (Woodward, 2011) to virtually increase the sample size. The Bayesian analysis is based on Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling, allowing us to implement an algorithm of 10,000 simulations in the models presented here. In all of the simulations, the first 4000 initial MCMC samples were discarded (“burn-in”) under an assumption of convergence past this point (Woodward, 2011). We used informative prior normative data based on the observed data. We assumed a Poisson distribution for the independent effects and covariate regression coefficients as per prior distributions. We excluded other prior distributions using the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) as implemented in the arm package(Gelman et al., 2015). We re-ran the simulations and models using a Poisson distribution, which appeared closer to the observed distribution for the dependent variable, time to first heavy drinking day.

As suggested by Spiegelhalter et al. (Spiegelhalter et al., 2002), we chose the Bayesian model with the lowest DIC value, which indicates that the model best predicts a replicate dataset that has the same structure as that currently observed. Finally, to evaluate the effect of arm assignment and other independent variables on the number of days to first heavy drinking day, we used Bayesian estimated regression parameters and the estimates of the standard error and confidence limits to derive a multivariate Generalized Linear Model, with a significance level of p<0.05. Models presented in Table 4 are those with the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) value indicating the most parsimonious multivariate model.

Table 4.

Time to First Heavy Drinking Day by Age and Treatment Arm*

| Age Groups Category, years | XR-NTX Arm | Placebo Arm | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20–29 | 24.1 Days | 9.5 Days | <0.001* |

| 30–39 | 78.9 Days | 73.9 Days | 0.41 |

| 40–49 | 98.8 Days | 85.0 Days | 0.08 |

| 50+ | 60.3 Days | 64.1 Days | 0.64 |

| Total Average (100) | 80.4 Days | 73.5 Days | 0.28 |

Data Analyzed Through Multiple Imputation

3.4 Supplementary Analyses

Changes in mean craving between groups from baseline to months 4, 5 and 6 post-incarceration were assessed using an ANOVA, with a significance level of p=0.05. Using hepatic gradation guidelines, outlined by the National Institutes of Health Division on AIDS, (National Institutes of Health, 2004) elevations meeting criteria for grade 3 or 4 hepatic severity (5 times the upper limit of normal) for laboratory based hepatic enzymes (AST ≥175 units per liter [U/L], ALT ≥195 U/L, and GGT ≥ 475 U/L) were assessed over time and between treatment arms using an ANOVA, with a significance level of p=0.05.

4.0 Results

4.1 Baseline Characteristics

A total of 100 participants were randomized (2:1) to receive either XR-NTX or placebo (n=67 XR-NTX, n=33 placebo). There were no statistically significant baseline differences between the treatment arms (Table 1). They were mostly male (77%), black (65%), in their mid-40s, and half (51%) completed high school equivalency. Most participants transitioned from jail (70%) and spent on average 13 months incarcerated. ART coverage was high (87%), 67% were HIV virologically suppressed (<400 copies/mL) and 35% were maximally suppressed (<50 copies/mL). In addition, a majority (60%) of participants met criteria for a cocaine use disorder using the M.I.N.I. while 15.6% had an opioid use disorder.

4.2 Pre-incarceration Alcohol Use Characteristics

Participants had an average duration of 11 years (SD ±12.94 years) of drinking to intoxication using the ASI (McLellan et al., 1992; Rikoon et al., 2006), with 87% of the participants meeting AUDIT criteria for dependent drinking level (score ≥20). Pre-incarceration alcohol consumption was measured for the 90 days before incarceration. The median of the average drinks per drinking day for the whole sample was 21.6 drinks per day. The mean number of drinking days, was 78.0 days and the mean percent heavy drinking days was 85.6% of days. Mean alcohol craving score was 3.8 pre-incarceration. There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups for these four variables over the 90-day pre-incarceration period (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in Alcohol Use Outcome Comparing Pre- and Post-Incarceration Variables

| Alcohol Outcome Means | Pre-Incarceration (90 Days) | Post-Incarceration (180 Days) | Average Decrease Pre- to Post-Incarceration | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XR-NTX | Placebo | Combined | XR-NTX | Placebo | Combined | XR-NTX | Placebo | Combined | ||||||||||

| Injections Received | 0–3 | 4–6 | 0–3 | 4–6 | 0–3 | 4–6 | 0–3 | 4–6 | 0–3 | 4–6 | 0–3 | 4–6 | 0–3 | 4–6 | 0–3 | 4–6 | 0–3 | 4–6 |

| Median Time to First Heavy Drink | - | - | - | - | - | - | 63.3 | 108.3 | 71.1 | 85.6 | 65.8 | 100.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Average Drinks per Drinking Day | 28.8 | 23.3 | 34.4 | 24.9 | 30.5 | 23.9 | 13.5 | 8.6 | 12.2 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 9.6 | −18.8 | −17.4 | −29.6 | −14.9 | −23.3 | −16.6 |

| Median Percent Heavy Drinking Days | 62.2 | 71.2 | 73.2 | 66.5 | 65.8 | 69.6 | 24.6 | 7.6 | 21.9 | 11.6 | 23.7 | 9.0 | −38.3 | −63.6 | −51.3 | −54.9 | −42.5 | −60.6 |

| Median Number of Drinking Days | 59.4 | 66.8 | 67.4 | 65.6 | 62.0 | 66.4 | 45.1 | 28.2 | 44.5 | 27.21 | 44.9 | 27.9 | −14.5 | −38.6 | −22.9 | −38.4 | −17.3 | −38.5 |

| Median Alcohol Craving | 4.0 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.9 | −1.9 | −1.8 | −3.5 | −2.4 | −2.3 | −2.0 |

4.3 Post-incarceration Alcohol Outcomes

4.3.1 Time to first heavy drinking day

Using Bayesian simulation modeling, there was no significant difference between the treatment arms on bivariate analysis for time to first heavy drinking day. Overall, the average time to first heavy drinking day was 80.0 days, without any difference by treatment arm (80.4 vs. 73.5 days; p=0.77). Length of incarceration, housing status, and race/ethnicity did not significantly influence the outcomes. Furthermore, when examining the time to first heavy drinking day by treatment arm and treatment intensity, we saw the longest time to first heavy drinking day for those who received 4 or more injections of XR-NTX (108.3 days; Table 2).

Inspection of the data through simple sorting by age in relationship to time to heavy drinking, however, suggested further analysis. When adjusting for age (p<0.001), alcohol use severity using the AUDIT score categories (p<0.001) and not actively using cocaine or heroin post-incarceration (p<0.001), there was a statistically significant association with a longer time to first heavy drinking day in participants who received XR-NTX compared to placebo (Table 3); for every increase unit in the model, there was an increase in number of days to first heavy drinking day. In a more granular analysis, participants aged 20 to 29 years receiving XR-NTX were significantly more likely to have a longer time to first heavy drinking day than those receiving placebo (24.1 vs. 9.5 days; p <0.001). There was, however, no significant difference in this outcome in all other age groups (see Table 4). Depicted in Figure 3 is a Kaplan-Meier survival curve for time to first heavy drink for the younger age group and treatment arm. In similar analyses, alcohol use severity by AUDIT score and non-active drug use post-incarceration were not statistically significantly affected by study treatment arm.

Table 3.

Multivariate Models for Time to First Heavy Drinking Day

| Original Model

|

Model with Imputed Data

|

Model with Bayesian Simulations

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | z value | p value | Estimate | Standard Error | z value | p value | Estimate | Standard Error | z value | p value |

| Study Arm | 0.049 | 0.0326 | 0.0326 | 0.132 | 0.071 | 0.0621 | 1.1447 | 0.252 | 0.164 | 0.0235 | 6.985 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Use Severity, AUDIT criteria | −0.004 | −0.0046 | −2.662 | <0.001 | −0.006 | 0.0087 | −0.7038 | 0.482 | −0.008 | 0.0013 | −6.438 | <0.001 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||||

| 20–29 | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||||||||

| 30–39 | 1.100 | 0.1405 | 7.829 | <0.001 | 0.810 | 0.2035 | 3.9798 | <0.001 | 0.832 | 0.0759 | 10.959 | <0.001 |

| 40–49 | 1.564 | 0.1303 | 11.999 | <0.001 | 0.976 | 0.1685 | 5.7949 | <0.001 | 0.947 | 0.0718 | 13.198 | <0.001 |

| 50+ | 1.290 | 0.1333 | 9.672 | <0.001 | 0.729 | 0.1662 | 4.3863 | <0.001 | 0.795 | 0.0731 | 10.866 | <0.001 |

| Active Drug Use | −0.501 | 0.0296 | −16.953 | <0.001 | −0.483 | 0.0458 | −10.5510 | <0.001 | −0.458 | 0.0266 | −17.213 | <0.001 |

Figure 3.

Time to To First Heavy Drinking Day Longer in 20–29 years Age Group Receiving XR-NTX

4.3.2 Pre and Post-Incarceration Alcohol Consumption Outcome Variable Results

Data analyses based upon the intention to treat analysis approach using naïve and imputed datasets for the individual pre- and post-incarceration alcohol outcome variables (average drinks per drinking day, percent heavy drinking days, number of drinking days and alcohol craving) were not statistically significantly different between treatment arms (Table 2). We hypothesized that the variation in the number of injections received by treatment arm had an effect on the alcohol outcomes. We therefore evaluated the change in alcohol outcomes based upon treatment intensity, those who received more than 50% of study injections. As shown in Table 1, over 50% of subjects received 4 or more injections. Additionally, these analyses avoid repeated statistical tests and decreased probability of Type II error. Table 2 depicts the alcohol outcome variables by treatment arm and treatment intensity (0–3 study injections received versus 4–6 injections).

4.3.3 Average drinks per drinking day

The pre-incarceration to 6 months post-release change in average drinks per drinking day revealed no statistically significant difference between treatment groups and those who received more than 50% of study injections. Those who received 4 or more study injections in the placebo group reduced their average drinks per drinking day by 14.9 drinks, while those in the XR-NTX group reduced their average drinks per drinking day by 17.4 drinks. No statistical difference was found between average drinks per drinking day for the intervention period (180 days post incarceration), however those who received <4 study injections had higher average drinks per drinking day than those who received ≥4 injections (Table 2).

4.3.4 Percent of heavy drinking days

No statistically significant difference was observed in the change of mean percent of heavy drinking days pre- and post-incarceration between the intervention arms and treatment intensity, nor was there a significant difference between treatment arms and treatment intensity during the intervention period (Table 2).

4.3.5 Total number of drinking days

The change in median total number of drinking days from pre- to post-incarceration was found to have no statistically significant difference between groups and treatment intensity. Similarly, there was no difference found in treatment arms and treatment intensity for mean drinking days during the intervention period (Table 2).

4.3.6 Craving for Alcohol

There was no statistically significant difference in mean change in alcohol craving between the treatment groups and the number of injections as measured by a logistic regression analysis. Approximately 80 percent of the sample either reported no craving at the time of baseline through the last three months of the observation period, or reported decreased craving from baseline (Table 2).

4.3.7 Composite alcohol improvement score

A global alcohol improvement score was calculated as a composite score using the above 5 variables. A generalized linear regression model of imputed data demonstrated that participants who received 4 or more injections of XR-NTX were significantly more likely to have a higher alcohol consumption improvement score (p<0.005) than those who received 4 or more injections of placebo (Figure 4). Age, gender, and race did not affect the relationship between study arm and alcohol improvement scores.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Composite Alcohol Consumption Index, Stratified by Number of XR-NTX Injections

4.4 Adverse Events

There were no statistical differences of adverse events between the two study intervention groups as depicted in Table 5 for change in AST, ALT, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels (5× upper limit of normal). Injection-site infections, immediate sensitivity reactions, nausea, diarrhea, headache, fatigue or increased anxiety were within the known parameters of previous reported frequencies (Alkermes Pharmaceuticals, 2006).

Table 5.

Adverse Events

| XR-NTX | Placebo | Total Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | |||

| Transaminase level 5x Upper Limit of Normal | |||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | |||

| Baseline; N=98 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Month 6; N=65 | 4% (2) | 0% (0) | 3% (2) |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) | |||

| Baseline; N=98 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Month 6; N=66 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) | |||

| Day of Release; N=69 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Month 6; N=50 | 5% (2) | 0% (0) | 4% (2) |

|

| |||

| Any reported adverse events | 67 | 33 | 100 |

|

| |||

| Skin and Soft Tissue Infection | 0% (0) | 3% (1) | 1% (1) |

| Signs of Edema | 1% (1) | 3% (1) | 2% (2) |

| Immediate Injection Reaction | 16% (11) | 9% (3) | 14% (14) |

|

| |||

| Any reported adverse events | 51 | 20 | 71 |

|

| |||

| Injection Site Reaction | 1% (1) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) |

| Nausea | 19% (13) | 9% (3) | 16% (16) |

| Vomiting | 6% (4) | 3% (1) | 5% (5) |

| Diarrhea | 9% (6) | 3% (1) | 3% (3) |

| Decreased Appetite | 3% (2) | 3% (1) | 3% (3) |

| Increased Appetite | 0% (0) | 3% (1) | 1% (1) |

| Headache | 13% (9) | 9% (3) | 12% (12) |

| Dizziness | 7% (5) | 0% (0) | 5% (5) |

| Fatigue | 10% (7) | 3% (1) | 8% (8) |

There were no statistically significant differences between groups for all above adverse events.

No subjects discontinued due to significant adverse events.

5.0 Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that specifically assesses the effectiveness of XR-NTX on alcohol relapse outcomes among PLH with AUDs after release from an incarcerated setting. The sub-analysis examination of XR-NTX on alcohol treatment outcomes, however, provides new and important insights into the pathway by which alcohol treatment with XR-NTX impacts alcohol consumption patterns. Though the majority of prisoners with HIV and AUDs relapse to alcohol use within one year after release from incarceration, few if any CJS settings offer alcohol pharmacotherapies prior to discharge or at the time of release (Springer et al., 2011a; Springer et al., 2011b). Therefore, evaluating the effect of XR-NTX on alcohol consumption among PLH after being released from incarceration is a major public health priority. Previously, we provided preliminary evidence on the high acceptance of XR-NTX (Springer, 2012; Springer et al., 2014), correlates of retention on XR-NTX one month after release (Krishnan et al., 2015; Springer et al., 2015), as well as the hepatic safety among this population (Vagenas et al., 2014), suggesting it may be effectively implemented within the CJS. Key findings from this study are the lack of difference in alcohol consumption using Bayesian modeling, yet a number of new findings did emerge. This study is the first to evaluate the effects of XR-NTX on alcohol consumption outcomes among PLH, a secondary outcome in the parent study, using a validated and primary endpoint previously deployed in the COMBINE study; time to first heavy drinking day (Anton et al., 2006).

Key findings from this study that have implications for further treatment strategies with justice-involved PLH with AUDs include: 1) the improved effectiveness of XR-NTX on alcohol outcomes with younger (age 20–29 years) participants, 2) the reductions in alcohol consumption with participants who were retained on XR-NTX longer, and 3) no evidence of any new adverse consequences in PLH treated with XR-NTX.

Overall the two treatment groups did not have statistically significant differences for the different individual pre-and post-incarceration alcohol outcome consumption variables in the naïve, imputed or Bayesian modeling data evaluations; but given the level of missingness, our results are more applicable using as-treatment analysis more than an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis because assumptions about relapse were not assumed about missing data. The non-significant finding of Little’s MCAR test directly contradicted the standard ITT assumption that missingness equals failure, and indicated that further analysis based on treatment intensity (the number of injections each participant received) be explored.

Though the primary outcome for this secondary analysis of alcohol outcomes of the parent trial showed no differences between the XR-NTX and placebo groups, a number of factors may have contributed to this finding, including suboptimal retention on XR-NTX, small sample size, the proportion of participants with missing data and inability to measure differences in behavioral addiction treatment provided within prison or the influences of incarceration itself. Nonetheless, a number of sub-analyses provide new insights. For example, the overall aim of this analysis of alcohol outcomes was to assess time to first heavy drinking day as well as other outcomes related to alcohol consumption variables previously identified in Project MATCH and the COMBINE studies as described in a previously published protocol paper (Anton et al., 2006; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997; Springer et al., 2014). Using Bayesian simulation modeling, the finding that younger PLH with AUDs (age 20–29 years) receiving XR-NTX had a longer delay to first heavy drinking day compared to the placebo group is intriguing. Studies comparing NTX-based treatments were found to be effective with older patients with AUD (Barrick and Connors, 2002; Oslin et al., 2002). Three studies of oral NTX that all had small samples sizes conducted among adolescents (ages 15–19 years) and one with young adults (ages 18–21) have found favorable acceptance of oral NTX and reduction in drinks per drinking day and number of heavy drinking days when assessed in those with histories of heavy drinking (Deas et al., 2005; Leeman et al., 2008; Miranda et al., 2014; O’Malley et al., 2015). No studies to date have, however, evaluated specifically injectable formulation of NTX, XR-NTX, among young adults with AUDs. In the case of HIV disease, younger adults fare poorly along the HIV continuum of care and for those with AUDs, targeted treatment with XR-NTX might be warranted because younger persons have traditionally had problematic adherence, which may be overcome due to the long-acting formulation of XR-NTX. Younger PLH being released from CJS settings with severe AUDs could benefit from early prevention and treatment interventions to reduce the negative effects of long-term alcohol use including neurocognitive decline (Anand et al., 2010). The 3 month time-period immediately after release has been identified as a crucial period where released prisoners with HIV tend to relapse to alcohol and substance use disorders that negatively influences their health outcomes in the community (Springer et al., 2011a; Springer et al., 2004; Springer et al., 2011b), therefore assessing the proportion of participants who achieved at least 1 injection while incarcerated and 3 injections after release was considered clinically meaningful in the analysis. In addition sub analyses from the COMBINE study and from a published systematic review and confirmatory meta-analysis demonstrate that show that the most optimal alcohol treatment outcomes occur for those who are on naltrexone for at least 12 weeks (Bouza et al., 2004; Roozen et al., 2006). When using a composite alcohol improvement score, there was a statistically significant improvement in the composite alcohol score among those who received 4 or more XR-NTX injections as compared to the placebo group. A composite score generates a single summary measure that is more easily amenable to interpretation, and thus is more sensitive to data variance and subtle changes by reducing floor and ceiling effects. This suggests a global alcohol outcome response with XR-NTX that may not have been adequately captured by examining each outcome individually.

Importantly, this study included persons with high health and socioeconomic disparities who are typically not included in other clinical trials of pharmacotherapies for prevention of relapse to alcohol use. In contrast to previous studies of XR-NTX for treatment of AUD (Garbutt et al., 2005; O’Malley et al., 2007), this study included only PLH being released from an incarcerated setting of prison or jail, who were predominantly from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, and who had a high proportion of social, medical and psychiatric co-morbidities. It is critical that marginalized populations are included in clinical trials as they are most commonly deprived of treatments for AUDs and likely to derive the most benefit from alcohol relapse prevention interventions (Chitsaz et al., 2013; Di Paola et al., 2014; Krishnan et al., 2013; Meyer et al., 2014; Rich et al., 2011; Springer et al., 2011a; Springer et al., 2011b).

Through NIAAA’s recommended single screening question, we identified an at-risk drinking population that typically has not been evaluated in a routine manner in the CJS. The majority of the study population (approximately 90%) was further determined to have AUDIT ‘dependent drinking level’ pre-incarceration. Despite evidence that NTX-based treatments are effective in curbing alcohol use within community settings (Anton et al., 2006; Garbutt et al., 2005), participants reported never having been offered these alcohol pharmacotherapies prior to this study. This discrepancy in the availability and utilization of pharmacotherapy for AUDs in this particularly vulnerable group highlights a significant need to implement recommended screening and diagnostic measures and FDA-approved NIAAA-recommended alcohol pharmacotherapies. In addition, as previously reported, this group of PLH with previously unidentified high alcohol severity was highly receptive to pharmacologic treatment with XR-NTX, even in the setting of a double-blinded placebo controlled trial (Springer et al., 2015; Springer et al., 2014), suggesting that if offered, a high acceptance among PLH being released from the CJS would ensue.

The attrition rate for study visits and injections were different due to differences in the ability of participants to receive injections in certain circumstances. Injections were prohibited by the CTDOC in the correctional facilities if participants were re-incarcerated, and were not allowed during stays in other inpatient facilities (listed in Figure 2A) but study visits could be conducted (Figure 2B). Despite higher attrition for study injections, there was fairly low attrition for study visits (63% completed interviews at 6 months after release), suggesting that retention on treatment would likely be high since injections are unlikely to be prohibited in ‘real-world’ settings. Furthermore, the retention rates in this study are similar at 4 and 6 months to forms of treatment including XR-NTX for those with alcohol and opioid use disorders in community samples as well as CJS populations (Krupitsky et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2016; Vo et al., 2016). Last, there was a statistically significant greater retention in injections but not study visits among those receiving XR-NTX as compared to placebo, thus identifying a treatment effect.

Notably, there was no difference in liver function tests or other adverse events between groups despite high levels of hepatitis C infection and being on simultaneous ART.

5.1 Limitations

The parent study was powered to detect a 15–20% difference between the two treatment arms based on the proportion with an undetectable HIV viral load (<400 copies/mL) at 6 months mediated by reduction in alcohol use (Springer et al., 2014). It is possible that since the calculated power analysis for the primary parent study was aimed towards detecting a difference in HIV viral load suppression, there was not enough power to detect a difference in the other alcohol outcome variables besides time to first heavy drinking day. A separate post-hoc power analysis indicated that although originally powered for the HIV outcomes, there was sufficient power (.94) given the sample size and observed differences in the composite alcohol improvement score. In addition, there was an elevated level of missing data unfortunately common among studies that include participants with high degrees of social instability (criminal justice, unstable housing, comorbid cocaine and opioid use disorders, psychiatric illness). Through a detailed statistical assessment of missingness, the missing data was found to be missing completely at random and unrelated to treatment arm and thus qualified this analysis for application of Multiple Imputation and a more nuanced as-treated analysis. Importantly, similar analyses of studies among PLH with missing data using the reported statistical methods of imputation analyses within this manuscript have been previously published (Azzoni et al., 2015; Shenoi et al., 2012). In addition, performing multiple imputation of missing data in the setting of alcohol clinical trials has been found to result in more accurate estimates than other statistical methods (Hallgren and Witkiewitz, 2013).

Despite these limitations, the study results have important implications for clinical use of XR-NTX and future research studies of PLH with AUDs and those being released form the CJS including: 1) a population with severe AUDs and high psychosocial disparities being released from prison with a mean length of incarceration of 12 months accepts initial treatment even in a double blinded placebo controlled trial; 2) XR-NTX is tolerated and safe among this population; 3) XR-NTX can lengthen the time to first heavy drinking day among younger PLH being released from a CJS setting, thus providing a stabilization post-release period, a well-known time where persons released from jail or prison often relapse and among a young group who could benefit from earlier interventions to reduce immediate and long-term harms of alcohol use; and 4) the longer time to heavy drinking stabilization period may allow persons to maintain or achieve HIV viral suppression. What is evident is that the high rates of recidivism, comorbid homelessness, psychiatric illnesses, and comorbid substance use disorders including cocaine use disorders independently and together negatively impact retention on any form of treatment. Therefore, a concerted effort of integrated care involving alcohol and substance use prevention pharmacotherapy interventions is urgently needed to adequately assist PLH being released from CJS settings to the community in order to decrease the likelihood of relapse to alcohol use and improve HIV treatment outcomes.

6.0 Conclusion

XR-NTX is acceptable, safe and effective in lengthening the time to heavy drinking among those who are younger in age living with HIV and being released from a CJS setting, and higher treatment intensity is associated with greater overall global alcohol consumption improvement score. Integration of NTX-based pharmacotherapies to prevent relapse to alcohol use in this vulnerable population should be explored further.

Highlights.

XR-NTX lengthens time to heavy drinking among younger persons living with HIV (PLH) upon release from prison

XR-NTX reduces composite alcohol consumption after release from the criminal justice system (CJS) among PLH

XR-NTX is not related to any serious adverse events among PLH with Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs)

Acknowledgments

Funding: The research was funded by the National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA018944: Springer and Altice) and by the National Institutes on Drug Abuse for an Independent Scientist Award (K02 DA032322 for Springer) and for a career development award ( K24 DA017072 for Altice). The funders were not involved in the research design, analysis or interpretation of the data or the decision to publish the manuscript. The Extended-release naltrexone and placebo were provided in-kind as a result of an Investigator- initiated application by Alkermes Inc.

Footnotes

Author Disclosures

Contributors: Sandra Springer, MD Study co-Principal Investigator, designed study, conducted study, proposed manuscript idea, wrote majority of paper; Angela DiPaola, project coordinator, organized data, contributed to analyses and writing of manuscript; Marwan Azar, assisted in writing of paper; Archana Krishnan, assisted in analyses and writing of manuscript; Russell Barbour, chief biostatistician and conducted analyses in paper and assisted in writing; Frederick Altice, co-principal Investigator, assisted in design of study, and writing manuscript. All authors approved of the final manuscript before submission.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alkermes Pharmaceuticals. [accessed on January 4, 2010];VIVITROL™ Package Insert. 2006 http://129.128.185.122/drugbank2/drugs/DB00704/fda_labels/153.

- Amorim P, Lecrubier Y, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Sheehan D. DSM-IH-R Psychotic Disorders: procedural validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Concordance and causes for discordance with the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13:26–34. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)86748-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P, Springer SA, Copenhaver MM, Altice FL. Neurocognitive impairment and HIV risk factors: A reciprocal relationship. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1213–1226. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9684-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A, Group CSR. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzoni L, Barbour R, Papasavvas E, Glencross DK, Stevens WS, Cotton MF, Violari A, Montaner LJ. Early ART results in greater immune reconstitution benefits in hiv-infected infants: Working with data missingness in a longitudinal dataset. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders Identification test (AUDIT) World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barbor EA. The AUDIT, Guidelines for use in primary care. World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick C, Connors GJ. Relapse prevention and maintaining abstinence in older adults with alcohol-use disorders. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:583–594. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaujean AA. BaylorEdPsych, editor . R package version 0.5. 2012. R Package for Baylor University Educational Psychology Quantitative Courses. [Google Scholar]

- Bouza C, Angeles M, Munoz A, Amate JM. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: A systematic review. Addiction. 2004;99:811–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: Improving public health and safety. JAMA. 2009;301:183–190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitsaz E, Meyer JP, Krishnan A, Springer SA, Marcus R, Zaller N, Jordan AO, Lincoln T, Flanigan TP, Porterfield J, Altice FL. Contribution of substance use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes and antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected persons entering jail. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(Suppl 2):S118–127. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choirat C, Honaker J, Imai K, King G, Lau O. Zelig: Everyone’s Statistical Software. Version 5.0–9. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Conen A, Wang Q, Glass TR, Fux CA, Thurnheer MC, Orasch C, Calmy A, Bernasconi E, Vernazza P, Weber R, Bucher HC, Battegay M, Fehr J. Association of alcohol consumption and HIV surrogate markers in participants of the swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64:472–478. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a61ea9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Zalewski S, Leeman RF, Toll BA, Fucito LM, O’Malley SS. In with the old and out with the new? A comparison of the old and new binge drinking standards. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:2657–2663. doi: 10.1111/acer.12514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas D, May MP, Randall C, Johnson N, Anton R. Naltrexone treatment of adolescent alcoholics: An open-label pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:723–728. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Research, C.P, editor . Brief Symptom Inventory. 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paola A, Altice FL, Powell ML, Trestman RL, Springer SA. A comparison of psychiatric diagnoses among HIV-infected prisoners receiving combination antiretroviral therapy and transitioning to the community. Health Just. 2014:2. doi: 10.1186/s40352-014-0011-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, Loewy JW, Ehrich EW. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1617–1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Yu-Sang S, Masanao Y, Hill J, Grazia-Pittau M, Kerman J, Zheng T, Dorie V. R package version 1.8–6. 2015. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Saunders JB, Babor TF, Aasland OG, Amundsen A, Hodgson R, Grant M. The structure and correlates of alcohol dependence: WHO collaborative project on the early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--III. Addiction. 1993;88:1627–1636. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren KA, Witkiewitz K. Missing data in alcohol clinical trials: A comparison of methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:2152–2160. doi: 10.1111/acer.12205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M, Amelia I. A program for missing data. J Stat Software. 2011;45:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, King G, Lao O. Toward a common framework for statistical analysis and development. J Comp Graph Stat. 2008;17:892–913. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Roache JD. The COMBINE SAFTEE: A structured instrument for collecting adverse events adapted for clinical studies in the alcoholism field. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2005:157–167. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.157. discussion 140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, Braithwaite RS, Bryant KJ, Cook RL, Edelman EJ, Fiellin LE, Freiberg MS, Gordon AJ, Kraemer KL, Marshall BD, Williams EC, Fiellin DA. Risk of mortality and physiologic injury evident with lower alcohol exposure among HIV infected compared with uninfected men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Stephenson JJ, Montejano L, Wang S, Gastfriend DR. Persistence with oral naltrexone for alcohol treatment: implications for health-care utilization. Addiction. 2008;103:1801–1808. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Di Paola A, Winn T, Altice FL, Springer SA. Extended-release naltrexone could reduce relapse to alcohol use for criminal justice populations living with HIV who are transitioning to the community. 8th Academic and Health Policy Conference on Correctional Health; Boston, MA. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Wickersham JA, Chitsaz E, Springer SA, Jordan AO, Zaller N, Altice FL. Post-release substance abuse outcomes among HIV-infected jail detainees: Results from a multisite study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(Suppl 2):S171–180. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0362-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Dunbar GC. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiat. 1997;12:224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Friedmann PD, Kinlock TW, Nunes EV, Boney TY, Hoskinson RA, Jr, Wilson D, McDonald R, Rotrosen J, Gourevitch MN, Gordon M, Fishman M, Chen DT, Bonnie RJ, Cornish JW, Murphy SM, O’Brien CP. Extended-release naltrexone to prevent opioid relapse in criminal justice offenders. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1232–1242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Palmer RS, Corbin WR, Romano DM, Meandzija B, O’Malley SS. A pilot study of naltrexone and BASICS for heavy drinking young adults. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton J, Zieglgansberger W. Pharmacological mechanisms of naltrexone and acamprosate in the prevention of relapse in alcohol dependence. Am J Addict. 2003;12(Suppl 1):S3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2003.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM. HIV in Prisons, 2001–2010. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, D.C: 2012. [Accessed on September 22, 2012]. at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/hivp2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, Tate JP, Cook RL, Braithwaite RS, Bryant KJ, Edelman EJ, Gordon AJ, Kraemer KL, Maisto SA, Justice AC Veterans Aging Cohort S. Number of drinks to “feel a buzz” by hiv status and viral load in men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:504–511. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1053-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Cepeda J, Wu J, Trestman RL, Altice FL, Springer SA. Optimization of human immunodeficiency virus treatment during incarceration: Viral suppression at the prison gate. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:721–729. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Ray L, Blanchard A, Reynolds EK, Monti PM, Chun T, Justus A, Swift RM, Tidey J, Gwaltney CJ, Ramirez J. Effects of naltrexone on adolescent alcohol cue reactivity and sensitivity: An initial randomized trial. Addict Biol. 2014;19:941–954. doi: 10.1111/adb.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumola C. US Department of Justice, editor. Substance Abuse and Treatment, State and Federal Prisoners, 1997. 1999. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [accessed on December 12 2012];Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. 2005 Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publicationsPractitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/cliniciansguide.htm.

- National Institutes of Health. Division of AIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events. NIH; Bethesda, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Corbin WR, Leeman RF, DeMartini KS, Fucito LM, Ikomi J, Romano DM, Wu R, Toll BA, Sher KJ, Gueorguieva R, Kranzler HR. Reduction of alcohol drinking in young adults by naltrexone: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:e207–213. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Garbutt JC, Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Kranzler HR. Efficacy of extended-release naltrexone in alcohol-dependent patients who are abstinent before treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:507–512. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31814ce50d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Pettinati H, Volpicelli JR. Alcoholism treatment adherence: older age predicts better adherence and drinking outcomes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:740–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Horton NJ, Tibbetts N, Meli S, Samet JH. Uptake and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected people with alcohol and other substance use problems: The impact of substance abuse treatment. Addiction. 2004;99:361–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Li K, Yip B, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Alcohol use and incarceration adversely affect HIV-1 RNA suppression among injection drug users starting antiretroviral therapy. J Urban Health. 2003;80:667–675. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvan PH, Lee KJ, Simpson JA. The rise of multiple imputation: A review of the reporting and implementation of the method in medical research. BMC Med Res Meth. 2015a:15. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0022-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvan PH, White IR, Lee KJ, Carlin JB, Simpson JA. Evaluation of a weighting approach for performing sensitivity analysis after multiple imputation. BMC Med Res Meth. 2015b;15:83. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JD, Wohl DA, Beckwith CG, Spaulding AC, Lepp NE, Baillargeon J, Gardner A, Avery A, Altice FL, Springer S. HIV-related research in correctional populations: Now is the time. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:288–296. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikoon SH, Cacciola JS, Carise D, Alterman AI, McLellan AT. Predicting DSM-IV dependence diagnoses from Addiction Severity Index composite scores. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozen HG, de Waart R, van der Windt DA, van den Brink W, de Jong CA, Kerkhof AJ. A systematic review of the effectiveness of naltrexone in the maintenance treatment of opioid and alcohol dependence. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. J. Wiley and Sons; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Bonors L, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan M, Dunbar G. Reliability and Validity of the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): According to the SCID-P. Eur Psychiatr. 1997;12:232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar G. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoi SV, Brooks RP, Barbour R, Altice FL, Zelterman D, Moll AP, Master I, van der Merwe TL, Friedland GH. Survival from XDR-TB is associated with modifiable clinical characteristics in rural South Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M. Timeline followback: a technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) pp. 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, Van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J Stat Soc. 2002;64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA. Extended-Release Naltrexone for HIV+ Released Prisoners. No. 156. Alcohol Clin Exp Res Suppl. 2012;36:342A. [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Altice FL, Brown SE, Di Paola A. Correlates of retention on extended-release naltrexone among persons living with HIV infection transitioning to the community from the criminal justice system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;157:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Altice FL, Herme M, Di Paola A. Design and methods of a double blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of extended-release naltrexone for alcohol dependent and hazardous drinking prisoners with HIV who are transitioning to the community. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;37:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Azar MM, Altice FL. HIV, alcohol dependence, and the criminal justice system: a review and call for evidence-based treatment for released prisoners. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011a;37:12–21. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.540280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: Reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1754–1760. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Spaulding AC, Meyer JP, Altice FL. Public health implications for adequate transitional care for HIV-infected prisoners: Five essential components. Clin Infect Dis. 2011b;53:469–479. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS, Perdoni ML, Harrison LD. Drug treatment services for adult offenders: the state of the state. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32:239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagenas P, Azar MM, Copenhaver MM, Springer SA, Molina PE, Altice FL. The impact of alcohol use and related disorders on the HIV continuum of care: A systematic review: Alcohol and the HIV continuum of care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12:421–436. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0285-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagenas P, Di Paola A, Herme M, Lincoln T, Skiest DJ, Altice FL, Springer SA. An evaluation of hepatic enzyme elevations among HIV-infected released prisoners enrolled in two randomized placebo-controlled trials of extended release naltrexone. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;47:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo HT, Robbins E, Westwood M, Lezama D, Fishman M. Relapse prevention medications in community treatment for young adults with opioid addiction. Subst Abus. 2016;37:392–397. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1143435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley R. World Prison Population List. 10. University of Essex; London, England: 2014. [Accessed on September 14, 2015]. at: http://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/prisonstudies.org/files/resources/downloads/wppl_2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward P. An Excel GUI for WinBUGS. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2011. Bayesian Analysis made simple. [Google Scholar]