Abstract

Over the previous 4 years, the African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative for nurses and midwives has supported 12 countries to establish national continuing and professional development frameworks and programs, linking continuing education to nursing and midwifery re-licensure through technical assistance and improvement grants. However, lack of electronic media and rural practice sites, differences in priority content, and varying legal frameworks make providing accessible, certifiable, and up-to-date online continuing education content for the more than 300,000 nurses and midwives in the 17 member countries of the East, Central, and Southern Africa College of Nursing a major challenge. We report here on how the East, Central, and Southern Africa College of Nursing, with technical assistance from an Afya Bora Fellow, developed an online continuing professional development library hosted on their Website using data collected in a survey of nursing and midwifery leaders in the region.

Keywords: Africa, continuing professional development, midwifery, nursing, workforce

Nurses and midwives play a vital role in the delivery of health services, not just in Africa but across the globe (Thompson, 2002), and in resource-poor settings nurses provide nearly 90% of the services for patients accessing the health care system (ICAP, 2013). The need to strengthen nursing and midwifery capacity globally is well recognized through World Health Assembly (2011) resolutions addressing issues including nursing shortages, job retention, and recruitment problems. Increasingly, countries are establishing continuing professional development (CPD) requirements to ensure that nurses and midwives maintain on-going competencies and remain up to date on current best practices to meet population health needs (Johnson, 2013).

Several east, central, and southern Africa (ECSA) countries have identified lifelong learning in the form of continuing nursing education as a national priority in order for the nursing workforce to stay current and respond quickly to rapid changes in health care (African Regulatory Collaborative, 2013). The current definition of CPD varies country by country and, in some countries it is used synonymously with continuing nursing education, continuing medical education, short courses, in-service training, lifelong learning, as well as other terms (African Regulatory Collaborative, 2013). In-service training programs can be important tools in health workforce retention, such as with midwives in Tanzania (Tanaka, Horiuchi, Shimpuku, & Leshabari, 2015), can be used to strengthen service delivery as demonstrated with health workers in Rwanda (Cancedda, Farmer, Kyamanywa, & Riviello, 2014), and is an effective way to improve knowledge and confidence as seen with skilled birth attendants in Malawi and India (Evans et al., 2014). Given the numerous benefits, there is a growing international trend to require and regulate CPD completion for nursing and midwifery re-licensure (African Regulatory Collaborative, 2013).

Since 2011, with the support of the African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative (ARC), many countries have created national frameworks for nursing and midwifery CPD requirements linked to licensure renewal, including national level CPD programs in countries such as Botswana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe (Gross, Kelley, & McCarthy, 2015). However, despite increasing CPD requirements, nurses commonly face barriers to accessing CPD (Richards, & Potgieter, 2010; Tanaka et al., 2015). Due to workforce shortages, high volume patient loads, limited resources, and strained training facilities, as well as great distances to access in-person CPD trainings, nurses and midwives frequently lack opportunities to attend facilitated CPD trainings (African Regulatory Collaborative, 2013). One study from South Africa noted structural barriers, including the lack of adequate funding for continuing education and limited coordination for ongoing staff development (Richards, & Potgieter, 2010).

ARC supports south-to-south collaboration in the ECSA region and convenes nursing and midwifery leaders to address regulatory issues such as continuing education, scopes of practice, licensing, and accreditation of pre-service training (Gross, McCarthy, & Kelley, 2011; McCarthy, Zuber, Kelley, Verani, & Riley, 2014). To address issues of CPD access, ARC and the Afya Bora Consortium in Global Health Leadership supported the ECSA College of Nursing to develop a Website that was beta-tested with ARC and ECSA College of Nursing leaders in February 2014 and launched in September 2014. The ECSA College of Nursing is a professional body working in 15 ECSA countries to strengthen the nursing and midwifery professions and overall health in the region. Three thousand individual nurses and midwives, 15 nursing councils, and 12 nursing associations are current members of the ECSA College of Nursing with an estimated 323,951 nurses and midwives practicing in the ECSA region (World Health Organization, 2006). This project has the potential to make CPD content readily accessible to thousands of nurses and midwives in the region, support advancing CPD requirements, and allow for greater exchange of existing, accessible, online CPD content across the region.

Purpose and Aims

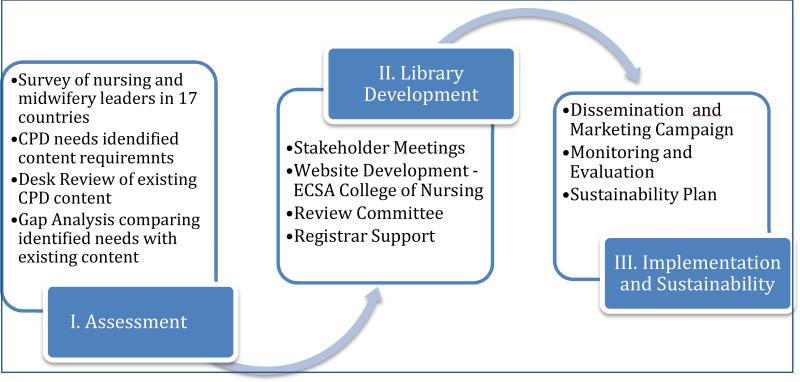

The purpose of our project was to develop and launch a CPD Library hosted on the ECSA College of Nursing Website by September 2014, monitor and evaluate the impact of the library, and develop a sustainability plan to support the library's on-going maintenance. We describe here the process of developing the CPD library, including initial content identification, as well as challenges in implementation and sustainability. Our project consisted of three phases [Figure 1]; this manuscript focuses primarily on the first two phases, including assessment and CPD library development. We present the results of the CPD library survey and gap analysis, highlight quality improvement efforts, and discuss lessons learned.

Figure 1.

Phases of development for the ECSA College of Nursing CPD Library.

Note. ESCA = east, central, and southern Africa; CPD = continuing professional development programs.

Methods

Study Design

Our study design used a mixed methods approach to identify content and develop and launch the ECSA College of Nursing CPD library. A survey was developed, piloted, and distributed to nursing and midwifery leaders. A desk review of available CPD resources was conducted, as well as a gap analysis to identify discrepancies between requested and available online CPD content. We used principles of participatory action research, collaborating with various nursing and midwifery leaders in every aspect of the process. The approaches were approved at the time of the Website launch in Harare, Zimbabwe, during a meeting with ECSA College of Nursing leaders from across Africa.

Participants

Survey participants included nursing and midwifery leaders from the 17 countries in the ECSA region, specifically targeting “quad members” who were active leaders in ARC. Quad members consisted of four to five national nursing and midwifery leaders with roles such as: (a) registrar or nursing council member, (b) representative from an academic nursing training institution or a country's ministry of education, (c) president of a national nursing association or union, or (d) the chief nursing officer for the ministry of health in each country. Countries included Botswana, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, Seychelles, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Procedures

Formative CPD library survey

An assessment was conducted to identify nursing and midwifery content needs for the CPD library, and to establish partnerships and buy-in with leaders in the ECSA region, particularly nurse registrars. A 15-question survey (Annex 1) was developed and piloted by the ECSA College of Nursing Secretariat, ARC faculty, an Afya Bora fellow, and select nursing leaders in the region, and was distributed via email to quad nursing and midwifery leaders from 17 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Survey responses were anonymous, and the answers were shared with ARC and ECSA College of Nursing leadership.

The survey used open-ended and closed-ended questions to assess: (a) the components, successes, and challenges of CPD efforts already in the region; (b) priority topics for CPD within each country; (c) resources available to be shared with the ECSA College of Nursing CPD library; and (d) feasible modes of delivery for ECSA College of Nursing CPD library content, such as Web-based links, downloadable information or memory stick utilization.

Desk review

A review was conducted of readily available online nursing and midwifery material to identify potential content for the CPD Library. The review started with known implementing partners and identified 46 potential modules between November 2013 and February 2014. Initial identification of Websites and organizations to analyze for the desk review was based on: (a) recommendations from nursing and midwifery leaders, (b) links from identified Websites, and (c) networking with implementation partners at international meetings.

Gap analysis

The aim of the gap analysis was to analyze information gathered from nurses in the region from survey and meeting discussions regarding content that should be included in the CPD library, and to compare this with what was currently available based on findings from the desk review. Results were presented at the ARC Learning Session in Nairobi, Kenya, in February 2014.

Participatory approach

A participatory approach was used to recruit and establish nursing and midwifery partnerships and buy-in with leaders in the ECSA region. Nursing and ECSA leaders received project updates and provided feedback at every stage of the development of the ECSA College of Nursing Website and CPD library. We used the qualitative method of participatory observations during meetings with nursing leaders to assess satisfaction with the progress of the CPD library; evaluations from two ARC regional meetings provided qualitative and quantitative assessments of stakeholder satisfaction with the CPD library development. Evaluations were distributed to meeting participants at the close of each day, and information related to the ECSA College of Nursing Website and CPD library presentation was extracted. Data from the surveys were entered into an Excel spreadsheet, analyzed, and shared in the form of an executive summary with ARC Faculty 2-4 weeks after each learning session.

Regular steering committee meetings were held with ARC faculty and ECSA College of Nursing leadership, both in-person and via Skype, which guided development of the CPD library and ECSA College of Nursing Website. ARC supported the salary for a Web developer and a Web administer from East Africa to be supervised by the ECSA College of Nursing Secretariat to help build sustainability and capacity. Registrars from 14 countries in the ECSA region provided strong support for the library, guaranteeing accreditation for CPD content evaluated and approved by the review committee.

Ethical Considerations

This project received institutional review board exempt status from Emory University, as the surveys were voluntary, anonymous, and an aspect of program development. Results of the survey were analyzed using descriptive statistics and presented at the ARC Learning Session held in Nairobi, Kenya, in February 2014. Phase III, involving the monitoring and evaluation framework, was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board, as the surveys were voluntary and anonymous and also an aspect of continuous quality improvement.

Results

The study population for our survey included nursing leaders, specifically the four quad members from 17 ARC countries. Sixty-eight nursing and midwifery leaders were contacted via email to complete the formative survey.

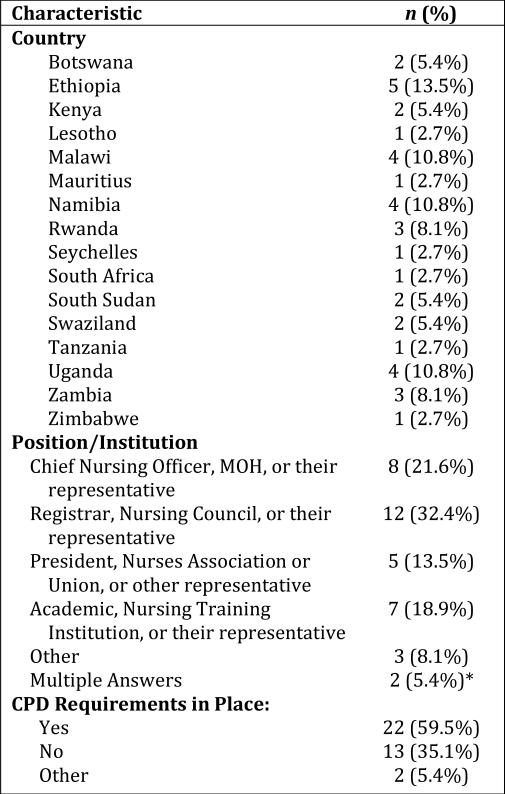

CPD Library Survey

Of the 68 nursing and midwifery leaders who received the 15-question CPD library survey, 37 responded, a response rate of 54%, with at least one response from every country except for Mozambique. More than 50% of respondents represented ministries of health or nursing councils. Institutional affiliation for the remaining respondents consisted of representatives from nursing associations or unions (13.5%), nurse training institutions (18.9%), and others (8.1%; see Figure 2). Other responses included: CPD Coordinator, Director of Programs and Professional Affairs on behalf of the General Assembly, and a private midwife. In two countries, Zimbabwe and Seychelles, the quad teams filled out one response together as a team instead of individually.

Figure 2.

CPD Library Survey: Participant demographics (n = 37).

Note. MOH = Ministry of Health; CPD = continuing professional development; * Two country quads completed this survey as a group

Countries varied in CPD requirements, including whether or not CPD was mandatory for re-licensure, when a national level CPD program had been established in their country, and tracking of CPD hours. Many countries (41%) reported having legal requirements for CPD in place for more than a year, including Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Seychelles, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe. Countries that did not have CPD requirements in place (23.5%) at the time of the survey included Ethiopia, Mauritius, South Sudan, and Zambia. Six countries had new CPD programs, or programs that were “due to start, but have not started yet,” including: Botswana, Lesotho, Rwanda, Swaziland, Tanzania, and Uganda. The length of time countries had had CPD requirements in place varied from newly started to more than 5 years. All countries that had CPD requirements used CPD logbooks and a database at the council to track CPD points, hours, or credits for licensure renewal. Only Swaziland reported using Web-based tracking online.

Nursing leaders encountered a variety of challenges in implementing CPD programs in their countries. Participants identified a lack of understanding of CPD requirements (71%) and limited resources and financial constraints (65%) as key challenges. Other challenges included limited access to CPD modules (53%), accreditation of CPD providers and linking CPD to licensure renewal (47%), creating awareness of the requirements (41%), and fostering buy-in from nurses (41%). Compared to other challenges, auditing nurses’ CPD was noted as less challenging to implement (24%). Two respondents chose all of the challenges offered. One respondent from Kenya noted: “There is critical shortage of nurses especially in the rural areas so being released to attend conferences is difficult. Secondly, where the nurses are supposed to pay, some find it difficult to afford in the midst of competing tasks.”

To address these challenges, nursing leaders identified an array of CPD implementation strategies. CPD implementation approaches included convening national nursing leaders for regular meetings (29.7%); establishing a national CPD committee (24.3%); forming specialized technical working groups (24.3%); utilizing assessment tools, CPD frameworks, or CPD resources developed by other countries (27%); engaging key nursing and midwifery stakeholders in the development and implementation of the CPD program (35.1%); involving other key implementing partners, ministries, and organizations (35.1%); incorporating CPD related activities into other ongoing nursing and midwifery activities of the ministry of health, nursing council, national nurses’ associations, and academic training institutions (35.1%); and developing a communication and marketing strategy for CPD (27%). Nearly a quarter of respondents (24.3%) indicated that they had not yet started implementing a national CPD program. Respondents from Swaziland and Kenya indicated using all the above implementation strategies (5.4%). Some additional comments included: “Several workshops have been organized for nurses and midwives sensitizing them on the importance and need for CPD requirements and portfolio building for licensure renewal. CPD providers have been sensitized to issue evidence of CPD points” (Seychelles). “ARC work was very useful to us because we didn't have to re-invent the wheel. Partners and the nurses association were also very useful” (Kenya). “The need to share CPD framework among ECSA College of Nursing member states” (Uganda). “A lot of problems still experienced on the ground with CPD” (Namibia).

ECSA countries reported having very few CPD resources readily available to share with other countries. Namibia and Malawi were the only countries that indicated they had resources (e.g., PowerPoint presentations, online courses, and training materials) that could be shared with the ECSA College of Nursing CPD library. One respondent from Namibia stated that they had a nursing ethics manual, as well as topics covering infection control and injection safety, hypertension, HIV and opportunistic infections, and the nursing process.

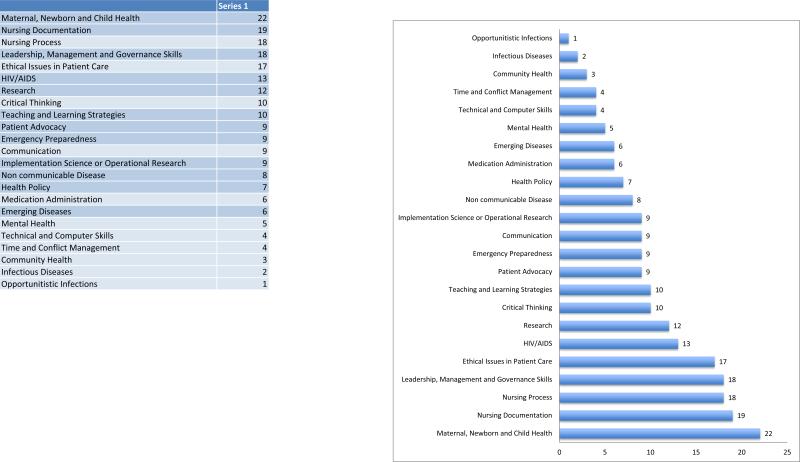

Nursing and midwifery leaders identified a number of topics of potential interest to nurses and midwives in their countries (Figure 3). Topics of interest included maternal, newborn, and child health (59.5%); nursing documentation (51.4%); leadership management and governance skills (48.6%); the nursing process (48.6%); ethical issues in patient care (45.9%); research (35.3%); HIV infection (35.1%); critical thinking (27%); teaching and learning strategies (27%); implementation science or operational research (24.3%); patient advocacy (24.3%); communication (24.3%); and emergency preparedness (24.3%). Less than a quarter of respondents reported an interest in non-communicable diseases, health policy, emerging diseases, mental health, medical administration, technical and computer skills, time and conflict management, community health, infectious diseases, or opportunistic infections.

Figure 3.

Topic Areas Identified

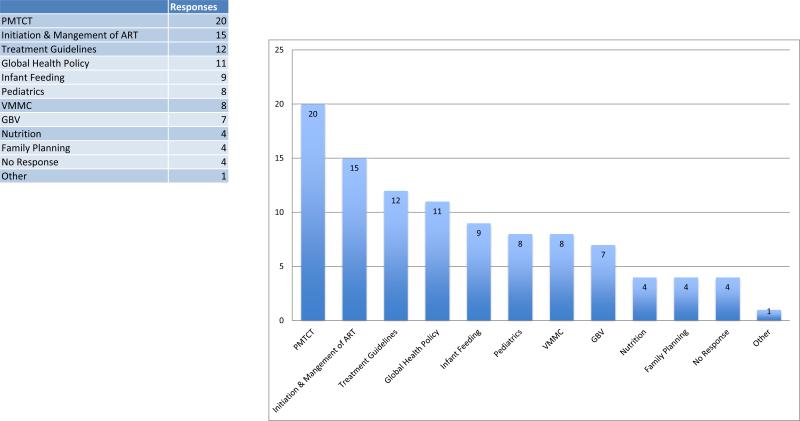

Nursing and midwifery leaders identified specific CPD topics that would benefit the nursing workforce in their countries to ensure relevant clinical competencies. Clinical topics included intensive care; coronary care; accident and emergency; management of intravenous infusions; calculations and maintenance of fluid balance charts; operations research; management of an unconscious patient; safe and effective clinical care; life saving skills; patient safety; counseling skills; maternal, newborn, and child health; health systems; general nursing procedures; management of post operative patients; care of critical patients; primary health care and prescribing by nurses; palliative care; customer care and communication; evidence-based practice; sexual and gender based violence; family planning including short and long term methods; health information management systems; attitude transformation; clinical audits; nurse and patient rights and obligations; clinical skill checks; coping with work in the presence of nursing staff shortages; action research for effective nursing care on the unit; self-care for nurses; cellphone use at work; nursing models used to improve care; and health promotion and prevention of disease. HIV topics noted as most relevant for ECSA countries included the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (54.1%), initiation and management of antiretroviral therapy (40.5%), treatment guidelines (32.4%), global health policy (29.7%), infant feeding (24.3%), pediatric care (21.6%), voluntary male medical circumcision (21.6%), gender-based violence (18.9%), nutrition (10.8%), family planning (10.8%) and emergency obstetric and neonatal care as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

HIV Module Topics Identified

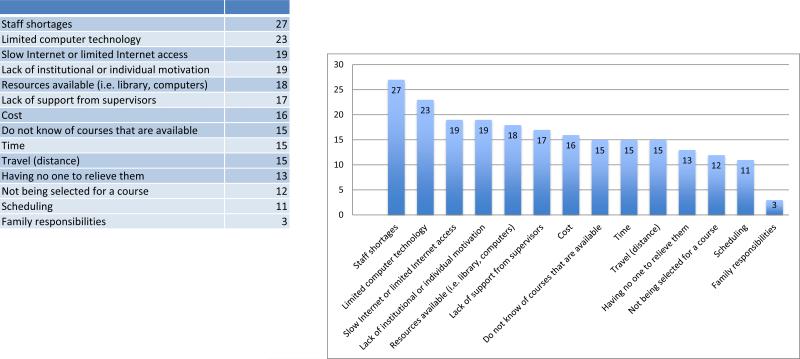

A number of potential barriers that could limit nurse and midwife access to CPD content were identified (Figure 5). These included staff shortages (73%), limited computer technology (62.2%), lack of institutional or individual motivation (51.4%), slow or limited Internet access (51.4%), available resources (e.g., library, computers; 48.6%), lack of support from supervisors (45.9%), cost (43.2%), time (40.5%), travel distance (40.5%), lack of awareness regarding available courses (40.5%), having no one to relieve them (35.1%), not being selected for a course (32.4%), scheduling (29.7%), and family responsibilities (8.1%). Two respondents selected all 14 provided options. Other potential barriers (13.5%) included, CPD as “not yet started,” as well as: “Lack of recognition and poor deployment even after a course.” “Lack of MOH (Ministry of Health) initiative.” “Training coming with specification of who should attend.” “No legalized counsel to think about CPD.”

Figure 5.

Barriers to CPD

Note. CPD = continuing professional development programs.

Question 14 asked about the preferred teaching and learning methods for each country. One participant filled in other with “simulation.” This question provided 15 methods for countries to choose from, and the responses were as follows: 21 (56.8%) formal lectures, 22 (59.5%) group discussion, 15 (40.5%) case studies, 11 (29.7%) self-directed reading, 12 (32.4%) modules (self-learning packages), 27 (73%) workshops or seminars, 8 (21.6%) role plays, 4 (10.8%) video instruction, 23 (62.2%) clinical on-site learning, 1 (2.7%) clinical off-site learning, 4 (10.8%) individual mentoring, 15 (40.5%) demonstration, 3 (8.1%) journal or reflective diary, 2 (5.4%) mobile learning (m-Learning), and 14 (37.8%) electronic learning. The most popular teaching and learning methods were Workshops and Seminars (27 responses), clinical on-site learning (23), group discussion (22), and formal lectures (21). Finally, question 15 probed the preferred method of delivery for training modules that the CPD Library could offer. For this question, there were six options and 35 nurses responded (94.6%) as follows: 24 respondents (64.9%) preferred Web-based, 30 (81.1%) PDF material available online, 23 (62.2%) content on a flash drive, 21 (56.8%) printed material, 21 (56.8%) video recordings, and 30 (81.1%) PowerPoint slides.

Desk Review Results

A total of 46 modules were collected for the desk review. Of the 46 modules presented at the ARC Learning Session, eight implementing partners had content reviewed. Sixteen partners were initially identified to be in the desk review, but many were excluded from the February 2014 presentation because they (a) did not offer CPD content but focused on other capacity building areas such as policy or research publications, (b) had a cost associated with their trainings, or (c) did not have modules available online or did not allow sharing of content to other Websites. The eight organizations identified in the desk review offered online education material in 12 of the 23 topic areas nurses identified in the survey. Most of the 46 CPD modules were found in the area of maternal, newborn, and child health at 14 (30.4%) modules; followed by 9 (19.7%) HIV; 5 (10.9%) infectious disease; 4 (8.7%) leadership, management, and governance skills; 3 (6.5%) in technical and computer skills; 2 (4.3%) research; 2 (4.3%) medication administration; 1 (2.2%) teaching and learning theories; 1 (2.2%) communication; 1 (2.2%) implementation science or operational research; 1 (2.2%) health policy; and 3(6.5%) other topics included blood bank practices, sexual health, and workplace violence. However, a number of nursing topics were not found in this desk review, including nursing documentation, ethical issues in patient care, emergency preparedness, mental health, emerging diseases, opportunistic infections, non-communicable diseases, time and conflict management, patient advocacy and critical thinking. Delivery method for CPD content by each of the eight selected implementing partners included 5 (63%) with downloadable PDFs or other information for download, 2 (25%) with online narrated modules that included pre- and post-test quizzes for content, 1 (12.5%) with online video lectures, 1 (12.5%) with a discussion forum, and 1 (12.5%) with case studies.

Participatory Approach Results

The desk review, CPD library survey, and gap analysis were presented at the ARC Learning Session, as well as at a CPD Satellite Meeting that took place just before the ARC Learning Session in Nairobi, Kenya in 2014. The Satellite Meeting included four executive ECSA College of Nursing members, as well as the ECSA College of Nursing Secretariat, the Emory Web Developer, the IT Specialist from ECSA College of Nursing, the Afya Bora Fellow, and three ARC Faculty members. At the meeting, discussions took place to include a review of the Website, creation of a CPD Module Review Committee that would approve CPD content on behalf of the ECSA College of Nursing, and discussions about sustainability.

After the meeting, registrars were solicited for support from the ECSA countries and the review committee was formed. To date, 14 registrars have signed letters supporting the ECSA College of Nursing CPD Library for use in their countries and 24 nurses and midwives in the region have applied to be on the CPD Library Review Committee. Minimum qualifications for the review committee included (a) proven professional experience in an area of specialty, (b) excellent English language written and communication skills (French and Portuguese to be added soon), (c) a minimum of an undergraduate degree in nursing or related fields, and (d) a masters or advanced degree in a related subject area would be an added advantage.

After the ARC Learning Session in February 2014, 16 modules found in the gap analysis were selected of the 46 by the Afya Bora Fellow and presented to the ARC and ECSA College of Nursing Leadership; then 10 of these 16 were selected for the initial launch, with a range of topics, but narrowed to five providers. Based on the gap analysis, survey, and feedback from participants in the region, the initial launching of the CPD library targeted content from seven of the target areas, with an emphasis on lower-technical needs, such as delivery mechanisms like PDF or PowerPoint presentations available for download, over streaming content.

A Web developer was contracted to develop the ECSA College of Nursing Website, as well as the CPD Library page, and it was beta-tested at the April 2014 ARC Learning Session in Lusaka, Zambia, for feedback. CPD Library reviewers evaluated the CPD modules for content that was relevant to the region and in line with international health policy recommendations before they were hosted on the ECSA College of Nursing Website. Another meeting was held just before the Website was launched on Monday, September 1, 2014, at the opening ceremony of the ECSA College of Nursing 5th Quadrennial Meeting and 11th Scientific Conference in Harare, Zimbabwe. During this meeting, nursing leaders from across the region provided feedback on how to best improve the ECSA College of Nursing Website and CPD Library, as well as their enthusiasm for the project.

The ECSA College of Nursing Website was launched at the meeting in Zimbabwe, but there were delays getting the CPD library portion fully online. The ECSA College of Nursing Website was developed on WordPress, by the initial Web developer, who did not meet the deadline of launching a functioning CPD library on the ECSA College of Nursing Website. The project was then taken over by a Web administrator hired at the ECSA College of Nursing offices in Arusha who worked to shift the CPD Library over to a Moodle platform, where there continued to be delays related to infrastructure challenges such as power and Internet outages, capacity of the Web administrator, and competing priorities within the organization. The CPD library was re-launched with 11 modules at the ARC meeting in Johannesburg, South Africa, 9 months later in July of 2015.

Discussion

Our survey and desk review revealed interest areas, access challenges, and gaps in CPD nursing and midwifery education delivery and content. There were 23 topic options and more than half of the interest was found in 7 topics, with maternal, newborn, and child health being the most popular topic (Figure 2); PMTCT was the most popular HIV-related module topic for nurses and midwives. Surprisingly, after maternal, newborn, and child health (which is arguably a large topic), 19 respondents identified modules on nursing documentation as a priority. Nursing documentation and nursing process were not found in the initial desk review but are areas of priority for nurses and midwives in the ECSA region. Because staff shortages were the biggest barrier to CPD completion in the region, online CPD content was explored. Preferred online CPD Library content delivery methods were PowerPoint and PDF material options. The implementing partners and educators should further explore online, accessible trainings in areas that could have training gaps, such as in nursing documentation.

Limitations and Challenges

For the researchers, it was hard to generalize information to different countries or regions; more participants are needed to be able to determine specific needs for each country. Also, some countries had their quad members complete the survey together, resulting in only one survey response in those countries. Mozambique is predominantly Portuguese speaking and they use translators at our meetings; because the survey was delivered in English, this could have been a barrier to their participation. Providing content that is geared toward Francophone or Lusophone countries and speakers is the next, more inclusive step. Additionally, even though the survey was sent to four quad members per country, Ethiopia had 5 responses, including three chief nursing officers and two academic or nursing training initiation representatives, indicating that some participants may have completed the survey twice, or that non-quad members participated.

Determining available CPD content with flexible partner organizations during the initial desk review was challenging because (a) organization Websites are not always intuitive and modules were often found in various places and difficult to locate, (b) content delivery methods varied and could have included anything from PDFs to voice-over PowerPoint presentations and videos, (c) some Websites had registration requirements to access content; (d) some organizations associated a cost with using their modules, and (e) some organizations did not have modules online and content was only available upon request.

Finally, time and resources were a challenge. With the global health care shortage, implementing a CPD project with participation from nursing leaders was sometimes challenging because of the time commitment required. More surprisingly, however, even hiring and using full-time Web development staff proved to take more time than expected due to challenges with infrastructure (power and Internet outages, computer crashes), and also because of competing priorities with the Web developer's time. Hosting the Website with ECSA College of Nursing, a vital partner as a professional organization with 15 member countries, was not financially sustainable and a lack of reliable power and Internet access added to this challenge. These challenges caused delays in the implementation of Phase III of the project, and the ability to promote the CPD library on the Website and monitor its usefulness for the region.

Conclusion

The CPD library will make expert-reviewed, high-quality CPD content accessible to more than 300,000 African nurses and midwives. Access to an online CPD library that contains modules for nurses and midwives in the ECSA region will help support national certification efforts and improve the knowledge and clinical expertise of users as well. There is demonstrated interest and support for the development of a CPD library in these 17 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, including political support from 14 nursing registrars who accept ECSA College of Nursing certifications of module completion for nursing and midwifery re-licensure purposes. Creation of a review committee to evaluate modules for the library was quickly achieved, also due to buy-in by nursing and midwifery educators, as well as other African health professionals.

However, sustainability strategies for the Website after funding for the Web-developer and Afya Bora Fellow runs out, will be necessary. Resource allocation in the form of contracting an implementing partner with extensive experience developing and maintaining Websites will be needed to support ECSA College of Nursing and the CPD Library project. Resources are needed to maintain the CPD library, to coordinate review committee activities, and to collect information on the functionality of the Website for quality improvement purposes. It is, therefore, recommended that the following steps be undertaken:

A plan for sustainability be developed that includes reaching out to developing partners, academic institutions, and other sources of funding, to cover the cost of maintaining and updating the CPD Library and ECSA College of Nursing Website, and a dedicated staff member be allocated, or an additional implementing partner be contracted, to provide IT support for the project.

A social marketing and awareness campaign be developed and piloted to target national Association and Union Presidents and other professional organizations in the ECSA region at ARC and ECSA College of Nursing meetings.

Implementation of a monitoring and evaluation strategy to capture information on usage patterns, barriers, and correlates of use for the ECSA College of Nursing Website and CPD Library that will also assess the ECSA College of Nursing CPD Library as an institutional capacity-building intervention for improved knowledge and skill acquisition for nurses and midwives.

Development and improvement of the CPD Library on the ECSA College of Nursing Website is the first step in this process. Sustainability through a maintenance plan for the library, country buy-in, and financial security will help ensure the capacity to continue the project beyond the initial support. Innovative strategies to promote, monitor, and evaluate the CPD library will be needed to ensure that it is a lasting resource that will contribute to improved safety and quality of nursing and midwifery practice in the ECSA College of Nursing region.

Key Considerations.

Continuing and professional development (CPD), while important to maintain skills in nursing and midwifery, are not readily available for many providers in the ECSA region.

In-person CPD training can pull providers out of clinical care in already resource-poor settings, so having access to online training modules that are accepted for re-licensure was an identified need for the ECSA region.

Topics related to nursing documentation; the nursing process; leadership, management, and governance skills; ethical considerations in nursing care, maternal-child health, and HIV care content was identified as high priority.

Trainings on PMTCT and initiation and management of ART were highlighted as having the highest interest in additional CPD training for HIV in the ECSA region.

Acknowledgements

The Afya Bora Fellowship is funded by a 5-year award (July 2012 to June 2017). Afya Bora is sponsored by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), President's Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and the Office of AIDS Research (OAR), a unit of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. This project is supported by PEPFAR, Office of AIDS Research, and U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, HRSA Grant Number: U91HA06801. Special thanks to African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative (ARC) Faculty, particularly Jessica M. Gross who was a Health Systems Consultant with ARC, as well as Maureen Kelley from Emory University. Additional thanks to ARC Faculty Patricia Riley, Jill Iliffe, and Carey McCarthy, as well as Alphonce Kalula from East, Central and Southern Africa College of Nursing (ECSACON), for fostering this collaboration and identifying high quality, culturally and politically relevant content to support the progress of this project. Thanks also for the professional developmental support for Kristen Hosey, an Afya Bora Consortium Fellow, provided by Joachim Voss from the University of Washington. We acknowledge the technological support and guidance given by Steven Wanyee, I-TECH, Kenya. And finally, we thank the nurses and midwives in the region who we hope will benefit from this project, and who have made this work possible.

Dr. Kristen Hosey receives research support from the Afya Bora Consortium in Global Health Leadership and consults for the East Central and Southern Africa College of Nursing (ECSACON) on behalf of the African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative for Nurses and Midwives (ARC) and the Task Force for Global Health.

Annex 1

ECSACON CPD Library Survey

ECSACON is working to create a continuing professional development (CPD) library to serve as a resource to countries in the ECSA region. The goal is to provide content-specific modules in areas of nursing and midwifery most relevant to countries’ identified needs. We hope that the creation of a robust CPD library will alleviate the need for each country to spend time and resources creating the same modules.

Purpose

This survey targets nursing leaders from the 17 countries in the ECSA region, which includes chief nursing officers, council registrars, association presidents, and academic representatives. This survey will assess areas related to CPD, including the:

Presence of CPD programs in the region, their key components, successes, and challenges

Content needs and topic areas of high priority for CPD trainings within each country

Resources already available in some countries for inclusion in the ECSACON CPD library

Identification and feasibility of various modes of delivery for CPD content.

Please take a moment to fill out the following survey. This survey should take about 5 minutes to complete. THANK YOU!

* Required

- Name of Country: * Mark only one oval.

- Botswana

- Ethiopia

- Kenya

- Lesotho

- Malawi

- Mauritius

- Mozambique

- Namibia

- Rwanda

- Seychelles

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- Swaziland

- Tanzania

- Uganda

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

- Institutional Affiliation: * Check all that apply.

- Chief Nursing Officer, Ministry of Health (or their representative)

- Registrar, Nursing Council (or their representative)

- President, Nurses Association or Union (or their representative)

- Academic, Nurse Training Institution (or their representative)

- Other:

- Is there a legal requirement for CPD for nurses and midwives in your country? Please describe: Check all that apply.

- Yes

- No

- Other:

Additional Comments:

-

4.If your country has CPD that is linked to licensure renewal, how long has this been in place? Mark only one oval.

- My country does not have a CPD program

- Less than 1 year

- 1-2 years

- 3-4 years

- 5-6 years

- 7+ years

- Other:

-

5.How does your country track CPD points, hours, or credits? Check all that apply.

- My country does not have CPD

- CPD logbook

- Database at council

- Web-based tracking online

- Other:

-

6.If you have started CPD in your country, what are the key components involved in CPD? Check all that apply.

- National CPD Framework with Guidelines

- Scope of CPD Activities and Programmes

- Publication and Dissemination of CPD Guidelines and Requirements

- Accreditation of CPD Activities

- Accreditation of Providers

- Linking CPD to Licensure Renewal

- CPD Learning Action Plans

- CPD Logbook

- Performance Appraisals of Providers and/or Facilitators

- Database to Track CPD Acquired by Nurses and Midwives

- Auditing

- Penalties for Noncompliance

- Other:

Additional Comments:

-

7.If you have started implementing a CPD in your country, what are some of the major challenges you have encountered? Check all that apply.

- Linking CPD to Licensure Renewals

- Accreditation of CPD Providers

- Creating Awareness the CPD Requirements and Guidelines

- Misunderstanding of CPD Requirements

- Engagement of Stakeholders

- Getting Buy-in or Compliance from Nurses and Midwives

- Access to Training Modules or Facilities

- Limited Resources and Financial Constraints

- Auditing

- Penalties for Noncompliance

- Other:

Additional Comments

-

8.If you have started implementing CPD in your country, what have proven to be the most effective strategies? Check all that apply.

- Regular meetings of the Quad

- Establishment of a national CPD committee

- Utilization of specialized technical working groups

- Utilized assessment tools, CPD frameworks or CPD resources developed by other countries

- Engagement of key nursing/midwifery stakeholders in the development and implementation of the CPD program

- Involvement of other key implementing partners, ministries, and organizations

- Incorporating CPD related activities into other ongoing nursing/midwifery activities of the Quad's organizations

- Development of a communication and marketing strategy for CPD

- Other:

Additional Comments:

-

9.Does your country have CPD resources (e.g. PowerPoint presentations, online courses, training materials) that could be shared with ECSACON to include in the CPD library? This could include materials that are web-based as well as others. Check all that apply.

- Yes

- No

If yes, list the CPD topic areas (e.g. pediatrics, HIV, etc.) that may be available and method of delivery (e.g. web-based, facilitator and participant manuals, slides, etc.):

-

10.

What topics for CPD modules would benefit nurses and midwives in your country the most in terms of ensuring clinical competency? (List at least five topics in priority order)

-

11.From the following CPD topics, what would be of priority for nurses and midwives in your country to learn? (Please, first go through the list below and then tick the top 6 which interest you most). Check all that apply.

- Emergency Preparedness

- Communication

- Nursing Documentation

- Medication Administration

- Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

- Mental Health

- Emerging Diseases

- Infectious Diseases

- HIV/AIDS

- Opportunistic Infections

- Non communicable Disease

- Nursing Process

- Leadership, Management and Governance Skills

- Time and Conflict Management

- Research

- Ethical Issues in Patient Care

- Patient Advocacy

- Critical Thinking

- Teaching and Learning Strategies

- Technical and Computer Skills

- Health Policy

- Community Health

- Implementation Science or Operational Research

- Other:

-

12.If ECSACON were to provide some modules on HIV/AIDS in the CPD library, what content would be relevant for your country? Check all that apply.

- Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT)

- Pediatrics

- Initiation and Management of ART

- Infant Feeding

- Nutrition

- Family Planning

- Treatment Guidelines

- Global Health Policy

- Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision (VMMC)

- Gender-based Violence (GBV)

- Other:

-

13.What barriers exist that could limit nurses and midwives from accessing CPD in your country? Check all that apply.

- Staff shortages

- Not being selected for a course

- Do not know of courses that are available

- Family responsibilities

- Having no one to relieve them

- Lack of support from supervisors

- Cost

- Time

- Travel (distance)

- Scheduling

- Slow Internet or limited Internet access

- Limited computer technology

- Resources available (i.e. library, computers)

- Lack of institutional or individual motivation

- Other:

-

14.What is the preferred teaching and learning methods for nurses and midwives within your country? Choose the top five preferences. If there are others, please add them in the comments. Check all that apply.

- Formal lectures

- Group discussions

- Case studies

- Self-directed reading

- Modules (self-learning packages)

- Workshops or seminars

- Role plays

- Video instruction

- Clinical on-site learning

- Clinical off-site learning

- Individual mentoring

- Demonstration

- Journal or reflective diary

- Mobile learning (m-Learning)

- Electronic learning (e-Learning)

- Other:

-

15.What types of delivery methods could the ECSACON CPD library use to be of benefit to your country? Check all that apply.

- Web-based

- PDF material available online

- Content on flash-drive

- Printed material

- Videoed recordings

- PowerPoint slides

- Other:

-

16.

Any additional comments:

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement:

Otherwise, the authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Kristen N. Hosey, School of Nursing and Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

Alphonce Kalula, Central, and Southern African College of Nursing (ECSACON), Arusha, Tanzania..

Joachim Voss, Department of Global Health and School of Nursing, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

References

- African Regulatory Collaborative Continuing and professional development for nurses and midwives: A toolkit for developing a national CPD framework. 2013 Jul; Retrieved from http://africanregulatorycollaborative.com/Documents/ARCCPDToolkitApril2014.pdf.

- Cancedda C, Farmer PE, Kyamanywa P, Riviello R. Enhancing formal educational and in-service training programs in rural Rwanda: A partnership among the public sector, a nongovernmental organization, and academia. Academic Medicine. 2014;89(8):1117–1124. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000376. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CL, Johnson P, Bazant E, Bhatnagar N, Zgambo J, Khamis AR. Competency-based training “Helping Mothers Survive: Bleeding after Birth” for providers from central and remote facilities in three countries. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2014;126(3):286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.02.021. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JM, Kelley M, McCarthy C. A model for advancing professional nursing regulation: The African health profession regulatory collaborative. Journal of Nursing Regulation. 2015;6(3):29–33. doi:10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30790-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JM, McCarthy CF, Kelley MA. Strengthening nursing and midwifery standards and practices in Africa. African Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2011;5(4):185–188. doi:10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30790-0. [Google Scholar]

- ICAP. Nurses and midwives: The frontline against HIV/AIDS. 2013 Retrieved from http://icap.columbia.edu/how-we-help/nursing-and-midwifery.

- Johnson P. Transforming and scaling up health professional education and training: Policy brief on regulation of health professions education. 2013 Retrieved from http://whoeducationguidelines.org/sites/default/files/uploads/whoeduguidelines_PolicyBrief_Regulation.pdf.

- McCarthy CF, Zuber A, Kelley MA, Verani AR, Riley PL. The African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative (ARC) at two years. African Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2014;8(2):4–9. doi: 10.12968/ajmw.2014.8.sup2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L, Potgieter E. Perceptions of registered nurses in four state health institutions on continuing formal education. Curationis. 2010;33(2):41–50. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v33i2.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Horiuchi S, Shimpuku Y, Leshabari S. Career development expectations and challenges of midwives in urban Tanzania: A preliminary study. BMC Nursing. 2015;8(14):27. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0081-y. doi:10.1186/s12912-015-0081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JE. The WHO Global Advisory Group on Nursing and Midwifery. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34(2):111–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Assembly Sixty-Fourth World Health Assembly: Strengthening nursing and midwifery. 2011 May; Retrieved from https://extranet.who.int/iris/restricted/handle/10665/3561.

- World Health Organization The world health report: Working together for health. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf?ua=1.