Abstract

Background:

The ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients due to stent thrombosis (ST) remain a therapeutic challenge for a clinician. Till date, very few researches have been conducted regarding the safety and effectiveness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with second-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) for STEMI caused by very late ST (VLST). This retrospective study evaluated the safety, efficacy, and outcomes of primary PCI with second-generation DES for STEMI due to VLST compared with primary PCI for STEMI due to de novo lesion.

Methods:

Between January 2007 and December 2013, STEMI patients with primary PCI in Fuwai Hospital had only second-generation DES implanted for de novo lesion (558 patients) and VLST (50 patients) were included in this retrospective study. The primary end points included cardiac death and reinfarction. The secondary end points included cardiac death, reinfarction, and target lesion revascularization. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) and compared by Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages, and comparison of these variables was performed with Chi-square or Fisher's exact test. A two-tailed value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed by SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA) for Windows.

Results:

In-hospital primary end point and the secondary end point were no significant differences between two groups (P = 1.000 and P = 1.000, respectively). No significant differences between two groups were observed according to the long-term primary end point and the secondary end point. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed no significant difference between the two groups in the primary end point and the secondary end point at 2 years (P = 0.340 and P = 0.243, respectively). According to Cox analysis, female, intra-aortic balloon pump support, and postprocedural thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow 3 were found to be independent predictors for long-term follow-up.

Conclusion:

Primary PCI with second-generation DES is a reasonable choice for STEMI patients caused by VLST.

Keywords: Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Second-generation Drug-eluting Stents, ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction, Stent Thrombosis

Introduction

Stent thrombosis (ST) is a rare but dreaded complication following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which may be associated with severe clinical outcomes, such as sudden death and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).[1] Drug-eluting stents (DES) have markedly decreased the restenosis rate, but ST is still the primary cause of STEMI after PCI.[2] With the improvement of stents design, more biocompatible polymers, thinner polymers layer, and better metallic platforms, second-generation DES are associated with lower rates of very late ST (VLST) than the first-generation DES.[3,4] According to the latest guidelines, primary PCI is the recommended treatment choice for STEMI due to de novo lesion.[5] However, there are few researches about the safety and effectiveness of primary PCI with second-generation DES for STEMI caused by VLST.[6] We needed to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and outcomes of primary PCI with second-generation DES for STEMI due to VLST compared with primary PCI for STEMI due to de novo lesion.

Methods

Patient populations

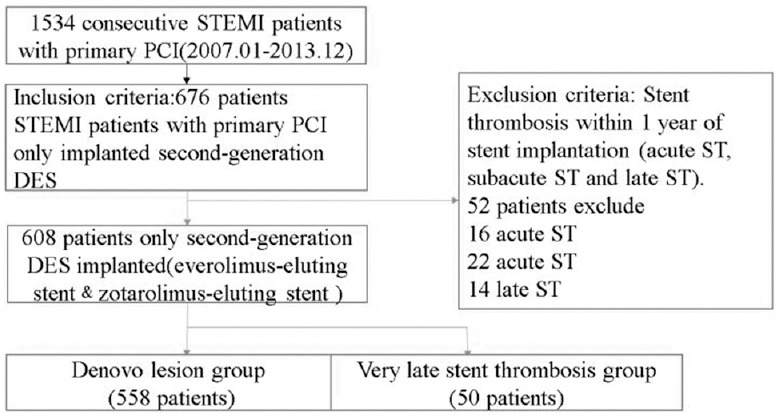

Between January 2007 and December 2013, 1534 consecutive patients with STEMI were admitted to primary PCI in Fuwai Hospital. The 608 remaining patients who had only second-generation DES (everolimus-eluting stent and zotarolimus-eluting stent) implanted in the course of the primary PCI for de novo lesion and VLST were included in this retrospective study [Figure 1]. The study inclusion criteria were the patients fulfilling STEMI diagnosis: (1) continuous typical chest pain lasted longer than 30 min, (2) electrocardiogram ST-segment elevation ≥2 mm in not <2 contiguous electrocardiography leads, and (3) symptom onset within 12 h or up to 18 h if there was evidences of continuing ischemia or hemodynamic instability. Exclusion criteria for the research included the development of ST within 1 year of stent implantation (acute ST, subacute ST, and late ST [LST]). VLST was defined according to the Academic Research Consortium.[7] The definition of primary PCI for VLST was considered a PCI due to STEMI, angiographic confirmed thrombus that originated in the stent or in the segment 5 mm proximal or distal to the stent. Accordingly, patients with primary PCI were divided in an ST group (fifty patients) and a de novo group (558 patients). Optimal primary PCI result was defined as final thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow 3 and residual stenosis <20% in the infarct-related artery at the end of the procedure.[8] The Institution Review Board of Fuwai Hospital approved the study protocol. The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for STEMI patients.

Analysis of patient data

The patient demographic characteristics, history of heart disease, and risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and current smoking) were obtained from medical records. A 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) was performed on each patient immediately on hospital admission, and myocardial infarction (MI) type was also defined from ECG.

Procedure

Primary PCI was carried out according to standard care. An initial bolus of 100 U/kg unfractionated heparin was administered at the beginning of procedure, and during the procedure, additional boluses were given to achieve an activated clotting time in area of 250–300 s. If the patients did not take aspirin before STEMI attack, they would be prescribed 300 mg chewable aspirin as soon as possible, and followed by 100 mg every day. A total dose of 600 mg clopidogrel was loaded before the procedure if the patient did not take clopidogrel previously, and followed by 75 mg every day. The use of embolic protection devices, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and thrombus aspiration was decided by the operator's discretion. Mechanical assistance devices (intra-aortic balloon pump [IABP]) were applied when hemodynamic support was needed.

After discharge from the hospital, dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) was recommended for 12 months for all patients who were implanted second-generation DES.

Angiographic analysis and clinical follow-up

Two experienced interventional cardiologists for both the primary PCI procedure and ST angiograms observed the coronary angiograms independently. In case of disagreement, the two reviewers would discuss and establish a consensus; otherwise, a third interventional cardiologist was consulted.

Clinical follow-up information (in-hospital and 2 years) was obtained from hospital records or by interview with patients, by their relatives directly, or by telephone. Follow-up information including the development of major adverse cardiac events was collected, predefined as cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial reinfarction (not clearly attributable to a no target vessel), target lesion revascularization (TLR).[7]

Study end points and definitions

The primary end points were in-hospital and long-term (2 years) cardiac death and nonfatal myocardial reinfarction. The secondary end points were device-oriented composite end points, including cardiac death, reinfarction, and TLR. Cardiac death was defined as any death due to proximate cardiac cause, unwitnessed death and death of unknown cause, and all procedure-related deaths. Reinfarction was defined as biomarker criteria, stable or decreasing values on two samples and 20% increase 3–6 h after the second sample. TLR is defined as any repeat percutaneous intervention of the target lesion or bypass surgery of the target vessel performed for restenosis or other complication of the target lesion. The target lesion was defined as the treated segment from 5 mm proximal to the stent and to 5 mm distal to the stent.[7]

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) and compared by Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and comparison was performed with Chi-square or Fisher's exact test. Cox regression analyses were conducted to identify independent predictors of the primary end point and the secondary end point. The variables tested in the multivariable models included age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, previous cerebrovascular accident, current smoker, MI history, anterior MI, single-vessel disease, ostial lesion, bifurcation lesion, total occlusion, type B2 or C lesion, preprocedural TIMI flow grade, postprocedural TIMI flow grade, number of stents per patient, diameter of stent, total stent length, IABP support, and thrombus aspiration and were selected by forward stepwise method. Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. In addition, the cumulative survival curves for two end points were constructed using Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences were assessed with the log-rank test. A two-tailed value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed by SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for Windows.

Results

Characteristics of patients

In 1534 consecutive patients with STEMI treated by primary PCI, fifty patients with VLST were implanted with second-generation DES and 558 patients with de novo lesion were implanted with second-generation DES; baseline clinical characteristics with and without ST are listed in Table 1. Patients with ST groups had similar baseline to patients with de novo STEMI but a higher rate of PCI and MI history.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of study patients

| Characteristics | ST group (n = 50) | De novo group (n = 558) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (IQR) | 58 (15.5) | 57 (17.0) | 0.561 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 44 (88.0) | 454 (81.4) | 0.243 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 30 (60.0) | 314 (56.3) | 0.611 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 39 (78.0) | 422 (75.6) | 0.708 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 16 (32.0) | 160 (28.7) | 0.620 |

| Previous cerebrovascular accident, n (%) | 3 (6.0) | 57 (10.2) | 0.461 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 26 (52.0) | 294 (52.7) | 0.926 |

| Family history, n (%) | 16 (32.0) | 136 (24.4) | 0.233 |

| MI history, n (%) | 36 (72.0) | 31 (5.5) | 0.000 |

| PCI history, n (%) | 50 (100.0) | 62 (11.1) | 0.000 |

| Bypass history, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 8 (1.4) | 0.541 |

| Anterior MI, n (%) | 29 (58.0) | 301 (53.9) | 0.581 |

| Baseline SYNTAX score, (mean ± SD) | 12.4 ± 9.4 | 12.1 ± 8.4 | 0.646 |

MI: Myocardial infarction; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: Standard deviation; IQR: Interquartile range.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics

Table 2 shows angiographic and procedural characteristics. Culprit lesions were similar in the two groups. Lesion characteristics were also similar. The number of stents per patients and diameter of stents were no significant differences but de novo lesion was treated with longer stents. The incidences of IABP support and thrombus aspiration were both no significant differences between two groups.

Table 2.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | ST group (n = 50) | De novo group (n = 558) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culprit lesion, n (%) | |||

| LMCA | 0 | 5 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| LAD | 29 (58.0) | 301 (53.9) | 0.581 |

| LCX | 7 (14.0) | 76 (13.6) | 0.940 |

| RCA | 14 (28.0) | 205 (36.7) | 0.218 |

| SVG | 0 | 3 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| Single-vessel disease, n (%) | 9 (18.0) | 155 (27.8) | 0.136 |

| Lesion in coronary ostium, n (%) | 9 (18.0) | 61 (10.9) | 0.134 |

| Bifurcation lesion, n (%) | 24 (48.0) | 212 (38.0) | 0.165 |

| Total occlusion, n (%) | 37 (74.0) | 399 (71.5) | 0.708 |

| Type B2 or C lesion, n (%) | 44 (88.0) | 511 (91.6) | 0.391 |

| Preprocedural TIMI flow ≤1, n (%) | 39 (78.0) | 430 (77.1) | 0.711 |

| Postprocedural TTMI flow = 3, n (%) | 48 (96.0) | 530 (95.0) | 0.130 |

| Number of stents per patient, n (IQR) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.784 |

| Diameter of stent, mm (IQR) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.447 |

| Total stent length, mm (IQR) | 22.5 (8.0) | 24 (14.0) | 0.001 |

| IABP support placed during procedure, n (%) | 8 (16.0) | 62 (11.1) | 0.300 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 23 (46.0) | 229 (41.0) | 0.496 |

| Medical treatment in-hospital, n (%) | |||

| Aspirin | 50 (100.0) | 554 (99.0) | 0.548 |

| Thienopyridines | 50 (100.0) | 552 (99.0) | 0.461 |

| Beta-blockers | 45 (90.0) | 517 (93.0) | 0.497 |

| Statins | 50 (100.0) | 536 (96.0) | 0.153 |

LMCA: Left main coronary artery; LAD: Left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX: Left circumflex coronary artery; RCA: Right coronary artery; SVG: Saphenous vein graft; IQR: Interquartile range.

In-hospital and long-term outcomes

The in-hospital and long-term outcomes (mean 24 months) after primary PCI are summarized in Table 3. Interestingly and different from previous studies, the primary end point in-hospital were no significant differences between two groups. Moreover, the secondary end point in-hospital was similar in both groups, even in-hospital TLR incidence had a trend toward higher in ST groups.

Table 3.

In-hospital and long-term (mean 24 months) cardiac events of all study patients

| In-hospital cardiac events | ST group (n = 50) | De novo group (n = 558) | Chi-square value | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 15 (2.7) | 0.085 | 1.000 |

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 2 (4.0) | 11 (2.0) | 0.903 | 0.290 |

| The primary end point in-hospital, n (%) | 2 (4.0) | 21 (3.8) | 0.007 | 1.000 |

| In-hospital TLR, n (%) | 2 (4.0) | 3 (0.5) | 6.745 | 0.056 |

| The secondary end point in-hospital, n (%) | 2 (4.0) | 22 (4.0) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Long-term cardiac events (including in-hospital events) | ST group (n = 50) | De novo group (n = 547)* | Chi-square value | P |

| Mortality, n (%) | 2 (4.0) | 28 (5.0) | 0.120 | 1.000 |

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 6 (12.0) | 31 (5.6) | 3.160 | 0.114 |

| The primary end point, n (%) | 7 (14.0) | 53 (9.5) | 0.942 | 0.332 |

| TLR, n (%) | 7 (14.0) | 24 (4.3) | 8.598 | 0.010 |

| The secondary end point, n (%) | 9 (18.0) | 67 (12.0) | 1.364 | 0.243 |

*n = 547 for de novo group (there was no follow-up for 11 patients). TLR: Target lesion revascularization.

Complete clinical follow-up information for 2 years was available in fifty patients (100%) for ST group and 547 patients (98.0%) for de novo group. No significant differences between two groups were observed according to long-term primary end point. The secondary end point at 2 years follow-up also did not differ between the two groups (18.0% vs. 12.0%, P = 0.243). Only TLR was higher in patients with ST (14.0% vs. 9.3%, P = 0.010).

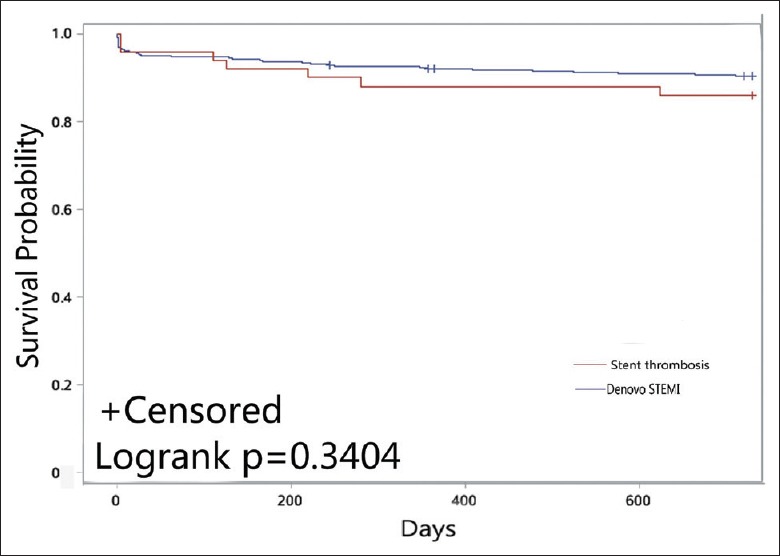

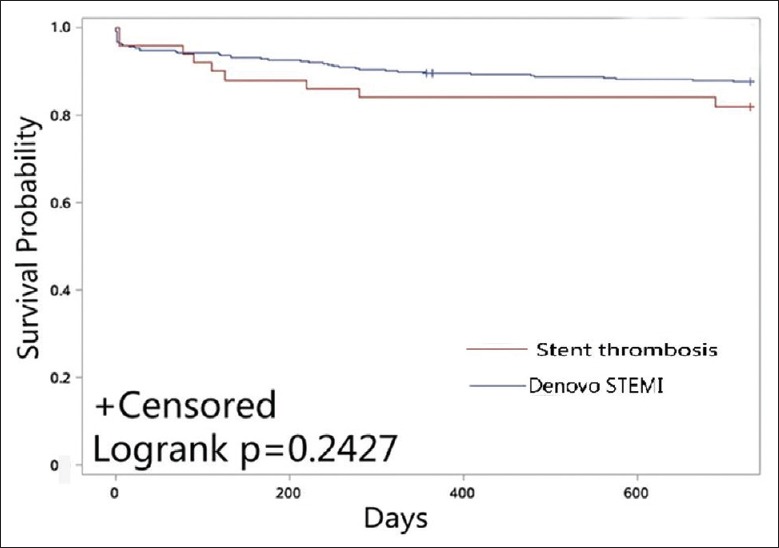

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed no significant difference between the two groups in the primary end point and the secondary end point at 2 years (P = 0.340 and P = 0.243, respectively), which is shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot for the primary end point.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plot for the secondary end point.

Independent predictors of the primary end point and the secondary end point at Cox analyses

According to Cox analysis, the independent predictors of the primary end point and the secondary end point are displayed in Table 4. Female, IABP support, and postprocedural TIMI flow 3 were found to be independent predictors of the primary end point for long-term follow-up. Moreover, female, IABP support, and postprocedural TIMI flow 3 also were considered independent variables of long-term outcome of the secondary end point.

Table 4.

Independent predictors of the primary end point and the secondary end point at Cox analyses

| Event | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| The primary end point | ||

| IABP support | 2.205 (1.197–4.063) | 0.011 |

| Female | 2.379 (1.395–4.058) | 0.001 |

| Postprocedural TIMI flow 3 | 0.328 (0.159–0.680) | 0.003 |

| The secondary end point | ||

| IABP support | 1.788 (1.003–3.189) | 0.049 |

| Female | 2.087 (1.281–3.399) | 0.003 |

| Postprocedural TIMI flow 3 | 0.318 (0.164–0.615) | 0.001 |

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; TIMI: Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; IABP: Intra-aortic balloon pump.

Discussion

This research was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of primary PCI with second-generation DES for STEMI caused by VLST in real world. From the analysis of the reported data, few but important findings were discovered. First, VLST is a relatively rare reason of STEMI. Second, primary PCI with second-generation DES is a reasonable choice for STEMI patients due to VLST. The primary end points and the secondary end point were no significant differences between two groups with the in-hospital and long-term follow-up. Third, female, IABP support, and postprocedural TIMI flow 3 were considered independent predictors of long-term outcomes.

ST was considered to be the last remaining obstacle in coronary interventional treatment,[9,10] in which 80% of patients presented as STEMI.[11] Over the past few years, STEMI patients treated with DES have become a key issue for fear of the risk of high incidence ST. Moreover, a series of large-scale evidence-based studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of DES in primary PCI.[12,13] But the STEMI patients due to ST, which have worse mortality and higher ST risk, remain a therapeutic challenge for the clinician. There are no recommended choices to guide treatment according to the latest guidelines.[5,14] Inconsistency opinions reflected weak evidence based on the field. The large randomized controlled trial was impractical to conduct because of the low spontaneous incidence. There might be very few number of VLST cases, even thousands of patients would be randomized.

Considering the severe thrombus burden of patients, most registries of ST experiments reported that thrombus aspiration might be able to improve the short- and long-term prognosis. Primary PCI displayed to be effective in infarct-related artery recanalization of STEMI patients due to ST, even if these patients’ reperfusion success rate was significantly lower, a higher rate of distal embolization was reported.[11] In the setting of a series of cardiovascular events, primary PCI for ST patients mirror the result of primary PCI for de novo patients. Hence, it should be considered the treatment of choice in this subgroup of STEMI patients.[15] In a previous report, balloon angioplasty was frequently used with repeat stenting (bare-metal stents [BMS] and DES) in more than 50% patients.[16] What is more interesting, no matter intracoronary fibrinolysis or balloon angioplasty or routine stent implantation is used, previous studies have shown poor results after any management strategies.[17,18,19] A large registry of Japanese research showed that implantation of a new sirolimus-eluting stent has been associated with adverse long-term outcomes at the time of ST.[19] Identified management strategies at the time of ST are very confusing in clinic practice, especially in the STEMI period, when quick decision-marking and great self-confidence are needed.

Different from previous researches,[15,20] STEMI patients due to LVST were not associated with a poor outcome compared with de novo STEMI in our study. Our research proved that primary PCI with second-generation DES was an advisability management strategy for STEMI patients due to VLST. Several issues could be considered in more detail to explain the finding. First, we selected a specific subgroup of patients. It is very important to recognize that the pathophysiology of LST/VLST is different from acute/subacute ST. Acute/subacute ST was thought to be associated with technical issues and suboptimal procedure, such as underexpansion, significant residual stenosis, edge dissections, or residual thrombus. Another underlying explanation was complex lesion, such as bifurcation lesion, severe calcification, and small vessels. The lack of long-lasting time dual antiplatelet was also a common reason.[21,22] A recent study from France explored ST characteristics and mechanisms through optical coherence tomography (OCT); the results showed acute struts malapposition and severe underexpansion were the most frequently observed abnormalities in patients of acute/subacute ST. LST/LVST mechanism is more complex, in patients of LST/LVST, late-acquired malapposition due to vessel remodeling and ruptured neoatherosclerosis were most highly prevalent observed. The mechanism of late-acquired malapposition may be due to the thrombus between struts and vessel wall that dissolves over time. Neoatherosclerosis formation is related to endothelial dysfunction and chronic inflammation around stent struts, potentially enhanced by the presence of coating polymers.[23] The metallic platforms were exposed to the bloodstream, leading to thrombosis because of incomplete reendothelialization.[24] Hence, incomplete stent endothelialization also plays an important role in process. The significant difference between these subgroups is that the cumulative mortality risk was significantly lower in VLST patients compared with acute/subacute ST and LST.[19]

Second, our researches chose the second-generation DES. Second-generation DES have thinner struts stent platform and a more biocompatible/biodegradable co-polymers to induce less inflammation. Several large clinical studies have demonstrated that second-generation DES are associated with lower rates of ST compared with first-generation DES and BMS.[3,25] Pathological studies showed that second-generation DES offer a more rapid redothelialization and more complete endothelial coverage than first-generation DES. A Japanese study evaluated endothelial function after DES implantation, proved better endothelial function and greater endothelial coverage of ZES compared with paclitaxel eluting stent by acetylcholine infusion and OCT.[26] Furthermore, a recent large meta-analysis including 9673 primary PCI patients for STEMI, second-generation DES appeared with significantly lower incidence of VLST, target vessel revascularization and MI compared with BMS at 3 years, and second-generation DES are safer, more effective and may be an available choice for primary PCI.[27]

Third, the data were from a single high-volume PCI center. As we know, a high-volume angioplasty centers are associated with a lower mortality rate compared with low-volume centers for acute MI patients, and perform primary angioplasty faster.[28]

In our study, postprocedural TIMI flow 3 was thought to be an independent predictor for long-term follow-up according to Cox analysis. The importance of the optimal primary PCI result was confirmed in our data. In one previous study, ST patients associated with the poor outcome were attributed mainly to the worse angiographic optimal PCI result, only 80% ST patients had TIMI flow 3.[11] The worse postprocedural TIMI flow 3 was attributed to the limited application of thrombus aspiration, which was a very useful intervention to deal with the high thrombus burden in STEMI patients. In our study, thrombus aspiration was decided by the operator's discretion. The applications of thrombus aspiration were no different between two groups, and the proportions of postprocedural TIMI flow 3 were the same too. This might also affect the final result. In our study, sex was thought to be an independent risk factor in STEMI patients. Several potential explanations are for the sex differences: (1) women with more cardiovascular risk and older, (2) women with smaller coronary vascular diameter, and (3) more likely to conservative therapy, and different quality of care.[29]

Our study has several additional important limitations. First, this study carried the well-known limitation of the retrospective. Second, only patients with successful PCI implantation were eligible in our study, which impacts on the generalizability of our data. Third, the door-to-balloon time, which was very important for outcome, was not available in our research, because many data were not received.

In conclusion, primary PCI with second-generation DES is a reasonable choice for STEMI patients caused by VLST. No significant difference was found between the two groups in the primary end point and the secondary end point at 2-year follow-up. Female, IABP support, and TIMI flow 3 after PCI were found to be independent predictors for long-term follow-up.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81470486).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their friend Pierre Gerber for a professional grammatical check.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Min Chen

References

- 1.Eisenberg MJ, Richard PR, Libersan D, Filion KB. Safety of short-term discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy in patients with drug-eluting stents. Circulation. 2009;119:1634–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristensen SL, Galløe AM, Thuesen L, Kelbæk H, Thayssen P, Havndrup O, et al. Stent thrombosis is the primary cause of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction following coronary stent implantation: A five year follow-up of the SORT OUT II study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolh P, Windecker S, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The task force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandzari DE, Mauri L, Popma JJ, Turco MA, Gurbel PA, Fitzgerald PJ, et al. Late-term clinical outcomes with zotarolimus- and sirolimus-eluting stents 5-year follow-up of the Endeavor III (A randomized controlled trial of the medtronic endeavor drug [ABT-578] eluting coronary stent system versus the cypher sirolimus-eluting coronary stent system in de novo native coronary artery lesions) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.12.014. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Writing Committee Members, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang KN, Grandi SM, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Late and very late stent thrombosis in patients with second-generation drug-eluting stents. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:1488–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.04.001. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: A case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parodi G, Valenti R, Carrabba N, Memisha G, Moschi G, Migliorini A, et al. Long-term prognostic implications of nonoptimal primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:50–5. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20729. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capranzano P, Dangas G. Late stent thrombosis: The last remaining obstacle in coronary interventional therapy. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2012;14:408–17. doi: 10.1007/s11886-012-0283-9. doi: 10.1007/s11886-012-0283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan L, Nie SP. Efficacy of intra-aortic balloon pump before versus after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with cardiogenic shock from ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Chin Med J. 2016;129:1400–5. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.183428. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.183428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chechi T, Vecchio S, Vittori G, Giuliani G, Lilli A, Spaziani G, et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction due to early and late stent thrombosis a new group of high-risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.070. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, Brodie BR, Dudek D, et al. Heparin plus a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor versus bivalirudin monotherapy and paclitaxel-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in acute myocardial infarction (HORIZONS-AMI): final 3-year results from a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:2193–204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60764-2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60764-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabaté M, Brugaletta S, Cequier A, Iñiguez A, Serra A, Hernádez-Antolín R, et al. The EXAMINATION trial (Everolimus-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction): 2-year results from a multicenter randomized controlled trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.09.006. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alfonso F, Sandoval J. New insights on stent thrombosis: In praise of large nationwide registries for rare cardiovascular events. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:141–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.12.006. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parodi G, Memisha G, Bellandi B, Valenti R, Migliorini A, Carrabba N, et al. Effectiveness of primary percutaneous coronary interventions for stent thrombosis. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:913–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.12.006. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong EJ, Feldman DN, Wang TY, Kaltenbach LA, Yeo KK, Wong SC, et al. Clinical presentation, management, and outcomes of angiographically documented early, late, and very late stent thrombosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.10.013. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasdai D, Garratt KN, Holmes DR, Jr, Berger PB, Schwartz RS, Bell MR. Coronary angioplasty and intracoronary thrombolysis are of limited efficacy in resolving early intracoronary stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:361–7. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00136-2. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casserly IP, Hasdai D, Berger PB, Holmes DR, Jr, Schwartz RS, Bell MR. Usefulness of abciximab for treatment of early coronary artery stent thrombosis. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:981–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00519-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura T, Morimoto T, Kozuma K, Honda Y, Kume T, Aizawa T, et al. Comparisons of baseline demographics, clinical presentation, and long-term outcome among patients with early, late, and very late stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting stents: Observations from the registry of stent thrombosis for review and reevaluation (RESTART) Circulation. 2010;122:52–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.903955. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.903955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ergelen M, Gorgulu S, Uyarel H, Norgaz T, Aksu H, Ayhan E, et al. The outcome of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for stent thrombosis causing ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2010;159:672–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.032. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centemero MP, Stadler JR. Stent thrombosis: An overview. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10:599–615. doi: 10.1586/erc.12.38. doi: 10.1586/erc.12.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang H, Li Y, Chen Y, Fu GS. Shorter- versus Longer-duration Dual Antiplatelet therapy in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing drug-eluting stents implantation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chin Med J. 2016;129:2861–7. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.194663. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.194663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Souteyrand G, Amabile N, Mangin L, Chabin X, Meneveau N, Cayla G, et al. Mechanisms of stent thrombosis analysed by optical coherence tomography: Insights from the national PESTO French registry. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1208–16. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv711. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue K. Pathological perspective of drug-eluting stent thrombosis. Thrombosis 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/219389. 219389. doi: 10.1155/2012/219389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmerini T, Benedetto U, Biondi-Zoccai G, Della Riva D, Bacchi-Reggiani L, Smits PC, et al. Long-term safety of drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: Evidence from a comprehensive network meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.017. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murase S, Suzuki Y, Yamaguchi T, Matsuda O, Murata A, Ito T. The relationship between re-endothelialization and endothelial function after DES implantation: Comparison between paclitaxcel eluting stent and zotarolims eluting stent. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83:412–7. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25140. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philip F, Stewart S, Southard JA. Very late stent thrombosis with second generation drug eluting stents compared to bare metal stents: Network meta-analysis of randomized primary percutaneous coronary intervention trials. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88:38–48. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26458. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canto JG, Every NR, Magid DJ, Rogers WJ, Malmgren JA, Frederick PD, et al. The volume of primary angioplasty procedures and survival after acute myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1573–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005253422106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005253422106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conrotto F, D’Ascenzo F, Humphries KH, Webb JG, Scacciatella P, Grasso C, et al. A meta-analysis of sex-related differences in outcomes after primary percutaneous intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Interv Cardiol. 2015;28:132–40. doi: 10.1111/joic.12195. doi: 10.1111/joic.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]