Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the ability of urinary N-telopeptide (U-NTX) to gauge rate of bone loss across and after the menopause transition (MT). U-NTX measurement was measured in early postmenopause in 604 participants from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). We examined the association between U-NTX and annualized rates of decline in lumbar spine and femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) across the MT (1 year before the final menstrual period [FMP] to time of U-NTX measurement), after the MT (from time of U-NTX measurement to 2 to 4 years later), and over the combined period (from 1 year before FMP to 2 to 4 years after U-NTX measurement). Adjusted for covariates in multivariable linear regression, every standard deviation (SD) increase in U-NTX was associated with 0.6% and 0.4% per year faster declines in lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD across the MT; and 0.3% (lumbar spine) and 0.2% (femoral neck) per year faster declines over the combined period (across and after the MT) (all p < 0.01). Each SD increase in U-NTX was also associated with 44% and 50% greater risk of fast bone loss in the lumbar spine (defined as BMD decline in the fastest 16% of the distribution) across the MT (p < 0.001, c-statistic = 0.80) and over the combined period (across and after the MT) (p = 0.001, c-statistic = 0.80), respectively. U-NTX measured in early postmenopause is most strongly associated with rates of bone loss across the MT, and may aid early identification of women who have experienced fast bone loss during this critical period.

Keywords: BIOCHEMICAL MARKERS OF BONE TURNOVER, DXA, MENOPAUSE, OSTEOPOROSIS, GENERAL POPULATION STUDIES

Introduction

The menopause transition (MT) and early postmenopause are periods of rapid bone loss in women. Bone mineral density (BMD) begins to decline around 1 year prior to the final menstrual period (FMP), and continues to decrease in early postmenopause, with a slight reduction in rate of loss around 2 years after the FMP.(1) This period of rapid decline in BMD around the FMP has been called the transmenopause.(1) The pattern of bone loss around and after the FMP parallels changes in urinary N-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (U-NTX), a biochemical marker of type I collagen breakdown. U-NTX starts to increase 1 to 2 years before the FMP, peaks approximately 1 year after the FMP, and plateaus thereafter.(2) This raises the possibility that U-NTX measurement during the rapid phase of bone loss may be useful in assessing the rate of ongoing bone loss, and help clinicians identify women who are losing bone at a fast rate.

Identifying those who are rapidly losing bone across the MT and early postmenopause is important because this decline in bone mass is accompanied by changes in trabecular microarchitecture (decreased trabecular number, increased trabecular spacing, and conversion of trabecular plates to rods) that may reflect irreparable microarchitectural damage and increase fracture risk.(3,4) Indeed, the incidence of radial and vertebral fractures increases substantially in the first decade after the FMP.(5,6) This has prompted some investigators to suggest that the MT is a time-limited window of opportunity to intervene to prevent rapid bone loss and permanent microarchitectural damage.(7) But to test the efficacy of this approach, we first need to be able to identify the women at risk for fast bone loss across the MT and in early postmenopause.

Prior studies examining the ability of bone resorption markers to gauge the rate of bone loss have focused on late postmenopausal women or were limited by small sample size.(8–11) To our knowledge, there are no large studies examining the association between bone turnover markers and rates of bone loss during the transmenopause and early postmenopause, when bone loss is most rapid.

The primary aim of this study was therefore to assess the clinical utility of U-NTX measured in early postmenopause, and at least 12 months after the FMP, to gauge the rate of ongoing bone loss across and after the MT. We chose to examine U-NTX measured 1 year or more after the FMP for two reasons: (1) a woman does not know she is in postmenopause until a year has passed after the FMP; (2) prior to 1 year after the FMP, U-NTX will not have reached its MT-related peak and will not have plateaued.(2) We examined the association between early postmenopausal U-NTX and rate of bone loss over three periods around the FMP: (1) across the MT, defined here as the period from the start of the transmenopause (1 year before the FMP) to the time of U-NTX measurement; (2) after the MT, defined as the period from the time of U-NTX measurement in early postmenopause to a study visit 2 to 4 years later; and (3) combined across and after the MT, defined as from the start of the transmenopause (1 year before the FMP) to 2 to 4 years after U-NTX measurement.

A secondary aim of this study was to assess whether U-NTX measured earlier in the MT, in early or late perimenopause (before NTX has peaked and plateaued), can predict rates of bone loss across and after the MT, as well as early postmenopausal U-NTX.

Subjects and Methods

Study Sample

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) is a multicenter, community-based, longitudinal cohort study of the MT. At baseline, participants were aged 42 to 52 years, menstruating 3 months prior to screening, had an intact uterus with one or two ovaries, were not pregnant, were not lactating, and were not taking exogenous sex steroid hormones. The entire SWAN cohort included 3302 participants, enrolled at seven sites in the United States: Boston, MA; Chicago, IL; Detroit, MI; Pittsburgh, PA; Los Angeles, CA; Newark, NJ; and Oakland, CA. The SWAN Bone Cohort included 2413 participants from five SWAN sites; the Chicago and Newark sites did not conduct bone assessments. Among SWAN Bone Cohort participants, the bone resorption marker, U-NTX, was measured at baseline and annually thereafter until the eighth annual follow-up visit. BMD was measured at baseline and annually thereafter. Participants gave written informed consent, and sites obtained institutional review board approval.

Of the 2413 bone cohort participants, the exact date of the FMP was not known in 1182 women for reasons such as hysterectomy without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) and/or use of sex hormones prior to natural menopause. An additional 537 women did not have a U-NTX measurement in early postmenopause. Of the remaining women, 90 had taken bone-modifying medications prior to their early postmenopausal measurement of U-NTX. After excluding these three groups, we were left with a base sample of size 604 for this study.

FMP

FMP date for those who underwent natural menopause was defined as the last menstrual bleeding date reported during the visit immediately preceding the first visit at which participants were classified as postmenopausal (12 months of amenorrhea).

Predictors

U-NTX was measured from a non-first voided urine collected before 10:00 a.m. If a woman could not provide a urine sample before 10:00 a.m., the time of collection was recorded. Because BTMs show diurnal variation, we adjusted for time of urine collection in analyses (see Statistical Analysis). Specimens were stored at −20°C to −80°C at local sites (precise temperature not recorded) for up to 1 month until shipment to the Central Lab (Medical Research Laboratories, Highland Heights, KY, USA). At the Central Lab, all samples were stored at −80°C. U-NTX was measured using the Osteomark competitive inhibition enzyme immunoassay (nM bone collagen equivalents [BCE]; Osteomark, Ostex International Inc., Seattle, WA, USA; interassay coefficient of variation [CV] <12%; intraassay CV <8%). Urinary creatinine was measured using the Cobas Mira autoanalyzer (mM; Horiba ABX, Montpellier, France; interassay CV 4.1%; intraassay CV 0.6%). U-NTX was normalized by urinary creatinine and expressed in nM BCE/mM Cr.

We used U-NTX measured at the first SWAN visit at least 1 year after the FMP as the primary predictor, U-NTXE-POST. Secondary predictors were U-NTX measured at SWAN baseline when the women were either in premenopause or early perimenopause (U-NTXPRE/E-PERI), and U-NTX measured in late perimenopause (U-NTXL-PERI), identified as the first U-NTX measurement after at least 3 months of amenorrhea.

Outcomes

Lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD were assessed by DXA (Hologic QDR 2000 at Pittsburgh and Oakland sites; Hologic QDR 4500A at Boston, Los Angeles, and Michigan sites). The short-term in vivo measurement variability was 1.4% for the lumbar spine and 2.2% for the femoral neck.(1) Cross-site calibration was accomplished by circulating an anthropomorphic spine phantom. Standard quality control phantom scans were done prior to each BMD measurement session; these were used to adjust for machine drift when necessary. The Pittsburgh and Oakland sites upgraded from the 2000 to 4500A models at follow-up visit 8. These sites scanned 40 women on both their old and new machines to develop cross-calibration regression equations.

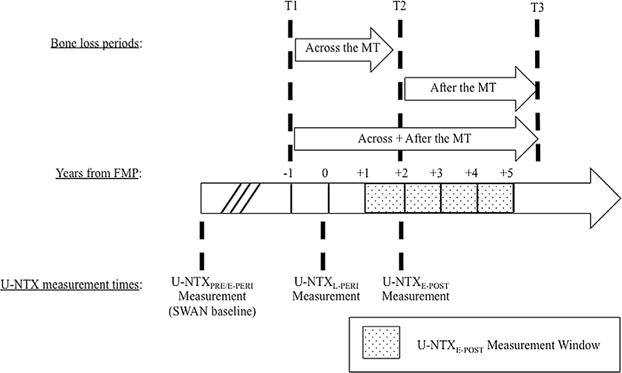

Ongoing rates of bone loss across and after the MT were calculated from BMD measurements made at the following three SWAN visits: the SWAN baseline visit (when all women were in premenopause or early perimenopause), the visit when U-NTXE-POST was measured, and a visit 2 to 4 years later. These BMD measurements were used to calculate annualized BMD decline rates (% decline per year) over the following three MT-related periods: (1) across the MT, defined here as the period from the start of the transmenopause (1 year before the FMP) (T1) to the time of U- NTXE-POST measurement (T2); (2) after the MT, defined here as the period from the time of U-NTXE-POST measurement to a study visit 2 to 4 years later (T3); and (3) combined across and after the MT, defined as from the start of the transmenopause (1 year before the FMP) to 2 to 4 years after U-NTX measurement (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The three periods over which rate of bone loss was assessed around the FMP. T1 refers to 1 year before the FMP when rapid bone loss has previously been shown to begin. T2 refers to the date in early postmenopause at which U-NTXE-POST was measured. T3 is the date at which a follow-up BMD measurement was obtained 2 to 4 years after T2. There were three time points at which U-NTX was assessed. (1) U-NTXPRE/E-PERI refers to U-NTX measured at SWAN baseline when women are premenopausal or early perimenopausal (<3 months of amenorrhea). We assumed that U-NTXPRE/E-PERI does not change significantly from SWAN baseline to T1. (2) U-NTXL-PERI refers to U-NTX measured when women are late perimenopausal (≥3 months of amenorrhea, not defined by relation to FMP). (3) U-NTXE-POST refers to U-NTX measured ≥1 and <5 years after the FMP. FMP = final menstrual period; U-NTX = urinary N-telopeptide.

Annualized BMD decline rate across the MT was calculated as the percentage of BMD lost from the SWAN baseline visit to the visit at which U-NTXE-POST was measured, divided by “T2 minus T1,” the time elapsed (in years) from the start of the transmenopause to the time of the U-NTX measurement in early postmenopause (Fig. 1). The implicit assumption is that there was minimal bone loss between the SWAN baseline and the start of transmenopause (T1). Annualized BMD decline rate after the MT was calculated as the percentage of BMD lost from T2 (the time of U- NTXE-POST measurement) to T3 (the follow-up visit between 2 and 4 years later), divided by “T3 minus T2,” the length of the period in years (Fig. 1). The annualized BMD decline rate over the combined larger period (Across+After the MT) was calculated as the percentage of BMD lost from the SWAN baseline visit to the T3 visit (between 2 and 4 years after the U-NTXE-POST measurement), divided by “T3 minus T1 ” in years. Unlike the first two estimates, which are based on BMD changes over periods that either precede or follow the U-NTXE-POST measurement, the third rate estimate assesses ongoing bone loss over a period that brackets the U-NTXE-POST measurement (Fig. 1).

In each of the three periods, we defined women with fast loss as those whose BMD decline rate was in the top 16% of the site- and period-specific distribution. These rates of bone loss are greater than one standard deviation (SD) above the mean BMD decline rate, and one in six women meet this criterion; note that one in six women will have a hip fracture in her lifetime.(12)

Covariates

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height measurements [BMI = weight in kg/(height in m)2]. FMP date for those who underwent natural menopause was defined as the last menstrual bleeding date reported during the visit immediately preceding the first visit at which participants were classified as postmenopausal (12 months of amenorrhea). Physical activity level was summarized by a score combining intensity with frequency of active living, home, and recreational physical activity from a modified Baecke interview.(13)

Statistical analysis

We used multivariable linear regression to assess the association between U-NTXE-POST and each of the three BMD decline rate estimates in separate models. We adjusted for the following time-constant covariates: ethnicity (white, African American, Chinese American, Japanese American), study site, time of urine collection, BMD at the start of the period over which decline rate was calculated, and an indicator variable that flagged the women whose BMD measurements used to calculate BMD decline came from different machines. We also adjusted for the following time-varying covariates obtained concurrently with U-NTX measurement: age (continuous); BMI (continuous), tobacco use (yes/no/unknown), alcohol use (<1 per week, <7 per week, ≥7 per week), and physical activity score.

To examine the ability of U-NTXE-POST to identify women with fast bone loss (fastest 16%), we used multivariable modified Poisson regression to model the risk of fast loss as a function of U-NTXE-POST and the covariates listed in the previous paragraph.(14) For comparison, we ran parallel models using U-NTX measured at SWAN baseline (U-NTXPRE/E-PERI) and U-NTX measured in late perimenopause (U-NTXL-PERI).

Results

Analytic sample descriptives

BMD decline rates over the three periods could not be calculated in all 604 women in the study sample, for a variety of reasons. BMD decline rate across the MT was available for 518 women; 86 participants had to be excluded because they were less than 1 year from the FMP at SWAN baseline, and a BMD measurement prior to the start of the transmenopause was not available. BMD decline rate after the MT was available in 483 women; 80 participants were excluded because they had no BMD measurement 2 to 4 years after the U-NTXE-POST measurement, and an additional 41 who used bone-modifying medications between the two BMD measurements at T2 and T3 were also excluded. The analytic sample for the combined Across+After MT decline analyses included 456 subjects (after excluding 86 who were within 1 year of the FMP at SWAN baseline, 45 missing BMD at T3, and 17 who used bone-modifying medications between T2 and T3). The three analytic samples were similar with respect to major characteristics (Table 1). At the time of U-NTXE-POST measurement, mean age was 52.6 to 52.9 years, mean time after the FMP was 1.6 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Analytic Samples

| Across the MT sample (n = 518)a |

After the MT sampleb (n = 483) |

Across+After MT sampleb (n = 456) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

| White | 243 (44.8) | 202 (41.8) | 200 (43.9) |

| African American | 126 (23.2) | 115 (23.8) | 100 (21.9) |

| Chinese American | 80 (14.8) | 78 (16.2) | 72 (15.8) |

| Japanese American | 93 (17.2) | 88 (18.2) | 84 (18.4) |

| At baseline (premenopause or early perimenopause) | |||

| Age (years) | 47.2 (2.4) | N/A | 47.3 (2.5) |

| Time before/after final menstrual period (years) | −4.0 (1.6) | N/A | −4.0 (1.6) |

| N-telopeptide, urine (nM BCE/mM Cr) | 33.8 (15.5) | N/A | 32.9 (14.3) |

| At time of urinary N-telopeptide measurement in late perimenopausea | |||

| Age (years) | 51.4 (2.4) | N/A | 51.4 (2.5) |

| Time before/after final menstrual period (years) | 0.04 (0.88) | N/A | 0.01 (0.88) |

| N-telopeptide, urine (nM BCE/mM Cr) | 44.3 (18.3) | N/A | 43.8 (18.7) |

| At time of urinary N-telopeptide measurement in early postmenopauseb | |||

| Age (years) | 52.8 (2.4) | 52.6 (2.5) | 52.9 (2.4) |

| Time before/after final menstrual period (years) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.5 (6.7) | 27.3 (6.5) | 27.4 (6.6) |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| < 1 beverage/week | 393 (75.9) | 365 (75.6) | 346 (75.9) |

| ≥1 and <7 beverages/week | 93 (18.0) | 86 (17.8) | 82 (18.0) |

| ≥7 beverages/week | 32 (6.2) | 32 (6.6) | 28 (6.1) |

| Tobacco smoking status | |||

| No | 386 (74.2) | 364 (75.4) | 340 (75.9) |

| Yes | 60 (11.6) | 62 (12.8) | 52 (11.4) |

| Unknown | 72 (13.9) | 57 (11.8) | 64 (14.0) |

| Physical activity score | 8.3 (2.1) | 8.4 (2.2) | 8.3 (2.0) |

| N-telopeptide, urine (nM BCE/mM Cr) | 47.2 (19.9) | 48.0 (19.9) | 46.8 (19.3) |

| Bone mineral density at start of respective periods | |||

| Lumbar spine (g/cm2) | 1.056 (0.131) | 0.991 (0.146) | 1.056 (0.131) |

| Femoral neck (g/cm2) | 0.822 (0.129) | 0.783 (0.124) | 0.822 (0.129) |

| Annualized rate of change in bone mineral density over respective periods | |||

| Lumbar spine (%/year) | −2.4 (2.1) | −1.4 (1.5) | −1.9 (1.0) |

| Femoral neck (%/year) | −1.7 (2.1) | −1.2 (1.6) | −1.4 (1.1) |

Values are count (percentage) for categorical variables; mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables. See Fig. 1 for definitions of the periods over which bone loss was assessed.

MT= menopause transition.

Urinary N-telopeptide was measured at the first study visit in late perimenopause.

See Fig. 1 for definition of early postmenopause. Urinary N-telopeptide was measured at the first study visit in early postmenopause.

U-NTX and rates of bone loss

The median time across the MT (defined in Fig. 1) was 2.5 years, and the interquartile range (IQR) was 2.2 to 2.8. Mean rate of BMD decline across the MT was 2.4% per year in the lumbar spine and 1.7% per year in the femoral neck. After adjusting for age, ethnicity, study site, BMI, tobacco use, alcohol use, and starting BMD, greater U-NTXE-POST was associated with faster declines in BMD at both the lumbar spine and femoral neck across the MT. Each SD increment in U-NTXE-POST was associated with 0.6% per year and 0.4% per year faster decreases in lumbar spine (p < 0.001) and femoral neck (p < 0.001) BMD, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations Between U-NTX and Rate of Bone Loss Across and After the MT

| Across the MT

|

After the MT

|

Combined Across+After the MT

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | p | Mean (95% CI) | p | Mean (95% CI) | p | |

| U-NTXE-POST | n = 518 | n = 483 | n = 456 | |||

| Lumbar spine BMD | −0.6 (−0.8 to −0.4) | <0.001 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.01) | 0.07 | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) | <0.001 |

| Femoral neck BMD | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2) | <0.001 | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.06) | 0.2 | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | <0.01 |

| U-NTXL-PERI | n=290 | n = 290 | ||||

| Lumbar spine BMD | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2) | <0.001 | N/Aa | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.07) | 0.002 | |

| Femoral neck BMD | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.1) | 0.01 | N/Aa | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.02) | 0.02 | |

| U-NTXPRE/E-PERI | n = 508 | n = 449 | ||||

| Lumbar spine BMD | −0.2 (−0.3 to 0.01) | 0.07 | N/Aa | −0.1 (−0.2 to −0.001) | 0.046 | |

| Femoral neck BMD | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 0.3 | N/Aa | −0.04 (−0.1 to 0.07) | 0.4 | |

Adjusted increment in annualized percent change in BMD per standard deviation increment in U-NTX, adjusted for age, ethnicity, body mass, tobacco use, alcohol use, physical activity score, sample collection time, BMD at the start of the period, and an indicator variable that flagged a change in DXA scanner during the period. See Fig. 1 for definitions of the three periods over which bone loss was assessed.

U-NTX =rinary N-telopeptide; MT=menopause transition; U-NTXE-POST=U-NTX in early postmenopause; BMD = bone mineral density; U-NTXL-PERI =U-NTX in late perimenopause; U-NTXPRE/E-PERI = U-NTX at study baseline (premenopause or early perimenopause).

Association not tested because U-NTX measurement was significantly earlier than the start of the period over which bone loss was assessed.

The median length of the period after the MT (defined in Fig. 1) was 3.0 years, and the interquartile range (IQR) was 2.9 to 3.1. Mean rate of BMD decline after the MT was 1.4% per year in the lumbar spine and 1.2% per year in the femoral neck. After adjusting for relevant covariates, U-NTXE-POST was not associated with the rate of BMD decline after the MT in either lumbar spine (p = 0.07) or femoral neck (p = 0.2) in multivariable linear regression (Table 2).

Mean rate of BMD decline over the combined period (Across+After the MT, defined in Fig. 1) was 1.9% per year in the lumbar spine and 1.4% per year in the femoral neck. After adjusting for relevant covariates, greater U-NTXE-POST was associated with faster declines in BMD at both the lumbar spine and femoral neck over the combined period. Each SD increment in U-NTXE-POST was associated with 0.3% per year and 0.2% per year faster decreases in lumbar spine (p< 0.001) and femoral neck (p< 0.01) BMD, respectively (Table 2).

To assess whether U-NTX measured earlier in the MT (before U-NTX has peaked and plateaued) can predict rates of bone loss across and after the MT, we also examined U-NTX measured at study baseline (U-NTXPRE/E-PERI)and U-NTX measured in late perimenopause (U-NTXL-PERI). The Spearman’s rank correlations between the three U-NTX measurements were: 0.43 (p< 0.0001) between U-NTXPRE/E-PERI and U-NTXL-PERI,0.48(p < 0.0001) between U-NTXL-PERI and U-NTXE-POST,and0.36(p< 0.0001) between U-NTXPRE/E-PERI and U-NTXE-POST.

After adjusting for age, ethnicity, study site, BMI, tobacco use, alcohol use, and starting BMD, greater U-NTXPRE/E-peri wasmarginally associated with faster bone loss at the lumbar spine across the MT (p = 0.07) and significantly associated with faster bone loss at the lumbar spine over the combined Across+After MT period (p= 0.04). However, U-NTXPRE/E-PERI was not associated with bone loss at the femoral neck in either period (Table 2). Adjusted for the same covariates, greater U-NTXL-PERI was significantly associated with faster bone loss across the MT at both the lumbar spine (p< 0.001) and femoral neck (p= 0.01), and with faster bone loss over the combined Across+After MT period at both the lumbar spine (p= 0.002) and femoral neck (p= 0.02) (Table 2).

U-NTX and risk of fast bone loss

The 84th percentile of BMD decline rate across the MT was 4.4% per year in the lumbar spine and 3.6% per year in the femoral neck. Fast bone loss across the MT (fastest 16%) was defined as BMD decline rates above these thresholds. After adjusting for the covariates listed above, greater U-NTXE-POST was associated with greater risk of fast BMD decline across the MT at both anatomic sites. Each SD increase in U-NTXE-POST was associated with 44% and 38% greater risk of fast bone loss across the MT in the lumbar spine (p< 0.001) and femoral neck (p< 0.001), respectively (Table 3). The ability of U-NTXE-POST (in combination with relevant covariates) to identify fast bone loss in the lumbar spine and femoral neck (as measured by the area under the receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curve [AUC]) was 0.80 and 0.76, respectively. The 84th percentile of the U-NTXE-POST distribution was 65 nM BCE/mM Cr. The sensitivity and specificity of U-NTXE-POST levels above 65 nM BCE/mM Cr for fast bone loss across the MT was 28.0% (95% CI, 18.7% to 39.1%) and 86.2% (95% CI, 82.6% to 89.3%), respectively, in the lumbar spine; and 29.3% (95% CI, 19.7% to 40.4%) and 86.5% (95% CI, 82.9% to 89.5%), respectively, in the femoral neck.

Table 3.

Associations Between U-NTX and Fast Bone Loss Across and After the MT

| Across the MT

|

After the MT

|

Combined Across+After the MT

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | p | Mean (95% CI) | p | Mean (95% CI) | p | |

| U-NTXE-POST | n=518 | n = 483 | n = 456 | |||

| Lumbar spine BMD | 1.44 (1.21 to 1.71) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.90 to 1.37) | 0.3 | 1.50 (1.18 to 1.89) | 0.001 |

| Femoral neck BMD | 1.38 (1.16 to 1.67) | <0.001 | 1.08 (0.87 to 1.35) | 0.5 | 1.38 (1.07 to 1.78) | 0.01 |

| U-NTXL-POST | n=290 | n = 290 | ||||

| Lumbar spine BMD | 1.59 (1.19 to 2.13) | 0.002 | N/Aa | 1.64 (1.12 to 2.38) | 0.009 | |

| Femoral neck BMD | 1.33 (1.00 to 1.78) | 0.04 | N/Aa | 1.37 (0.95 to 1.98) | 0.08 | |

| U-NTXPRE/E-PERI | n = 508 | n = 449 | ||||

| Lumbar spine BMD | 1.21 (0.98 to 1.49) | 0.08 | N/Aa | 1.57 (1.16 to 2.14) | 0.004 | |

| Femoral neck BMD | 1.14 (0.92 to 1.43) | 0.2 | N/Aa | 1.17 (0.87 to 1.60) | 0.3 | |

Adjusted risk ratio for fast bone loss (fastest 16% decline in BMD) per standard deviation increment in U-NTX, adjusted for age, ethnicity, body mass, alcohol use, physical activity score, sample collection time, BMD at the start of the period, tobacco use, and an indicator variable that flagged a change in DXA scanner during the period. See Fig. 1 for definitions of the three periods over which bone loss was assessed.

U-NTX = urinary N-telopeptide; MT = menopause transition; U-NTXE-POST = U-NTX in early postmenopause; BMD = bone mineral density; U-NTXL-PERI =U-NTX in late perimenopause; U-NTXPRE/E-PERI =U-NTX at study baseline (premenopause or early perimenopause);

Association not tested because U-NTX measurement was significantly earlier than the start of the period over which bone loss was assessed.

The 84th percentile of BMD decline rate after the MT was 2.8% per year in the lumbar spine and 2.7% per year in the femoral neck. Fast bone loss after the MT was defined as BMD decline rates above these thresholds. After adjusting for the same covariates, U-NTXE-POST was not significantly associated with the risk of fast bone loss after the MT in either the lumbar spine or femoral neck (Table 3).

The 84th percentile of BMD decline rate over the combined (Across+After the MT) period was 3.2% per year and 2.9% per year in the lumbar spine and femoral neck, respectively. Fast bone loss over the combined period was defined as BMD decline rates above these thresholds. After adjusting for covariates listed above, each SD increase in U-NTXE-POST was associated with 50% and 38% greater risk of fast bone loss in the lumbar spine (p = 0.001) and femoral neck (p = 0.01), respectively (Table 3). The ability of U-NTXE-POST (in combination with relevant covariates listed) to identify the fastest 16% decliners in lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD (as measured by the AUC) was 0.80 and 0.75, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of U-NTXE-POST levels above 65 nM BCE/mM Cr for fast bone loss over the combined (Across+After the MT) period was 28.9% (95% CI, 16.4% to 44.3%) and 85.6% (95% CI, 81.9% to 88.9%), respectively, in the lumbar spine; and 23.9% (95% CI, 12.6% to 38.8%) and 85.1% (95% CI, 81.3% to 88.4%), respectively, in the femoral neck.

In comparison to U-NTXE-POST, U-NTXPRE/E-PERI and U-NTXL-PERI were not as strongly associated with risk of fast bone loss across the MT and over the combined (Across+After the MT) period at either the lumbar spine or femoral neck (Table 3).

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to assess the ability of a bone resorption marker measured in early postmenopause to gauge the rate of bone loss across and after the MT, a period of rapid loss of bone mass in women. We found that higher levels of early postmenopausal U-NTX were most strongly associated with greater bone loss across the MT, and more strongly associated with rate of bone loss in the lumbar spine than in the femoral neck. In addition, when considered with relevant clinical covariates, early postmenopausal U-NTX was robust at identifying women with fast bone loss (fastest 16%). Prior studies have also found that higher levels of bone resorption markers are associated with faster rates of bone loss(8–10,15–18); however, the majority of these studies were in women who were 65 years and older and late postmenopausal.(8,9,16,18) The studies that included younger, early postmenopausal women were limited by small sample size, and lack of ethnic diversity.(10,17) One prior SWAN study did find that U-NTX measured at study baseline (when the women were premenopausal or early perimenopausal) is associated with the amount of bone lost and fracture over 8 years, but did not explicitly examine the rate of bone loss during the critical period around the FMP.(19)

Our key finding was that higher levels U-NTX measured early after a woman is determined to be postmenopausal is associated with faster BMD decline across the MT. When considered with covariates, early postmenopausal U-NTX identified those with fast bone loss with acceptable AUC values.(20,21) When considered without covariates, early postmenopausal U-NTX levels above 65 nM BCE/mM Cr were moderately specific for fast bone loss, but poorly sensitive. To enhance sensitivity, U-NTX may need to be combined with relevant clinical covariates (as suggested by robust AUC values when U-NTX is combined with covariates). Alternatively, U-NTX may need to be combined with markers of bone formation, because modestly high values of U-NTX could also lead to rapid bone loss if bone formation is not proportionally increased.

A second key finding was that U-NTX measured earlier in the MT (in pre-/early perimenopause or late perimenopause) is also associated with bone loss across the MT, but not as strongly as U-NTX measured in early postmenopause. This is probably because U-NTX values rise across the MT and do not peak until early postmenopause.(2) Waiting until 1 year after the FMP (ie, 2 years after onset of transmenopausal bone loss) to obtain the best estimate of bone loss across the MT and identify women for BMD screening is not a major drawback because the least significant change (smallest change that can be considered statistically significantly beyond measurement error) in serial DXA-based BMD measurements may be as high as 5.3% and 6.9% at the lumbar spine and femoral neck, respectively(22); this amount of bone loss is unlikely to occur within 2 years in most women.(1)

The association between early postmenopausal U-NTX and rate of BMD loss was also stronger at the lumbar spine than at the femoral neck. Our ability to accurately estimate the association between U-NTX and rate of femoral neck bone loss was likely attenuated because changes in femoral neck BMD after the MT were of the same order as the short-term in vivo variability in DXA-based BMD measurement.(1,16,22–24) The weaker associations seen between U-NTX and bone loss after the MT may also be the result of slower postmenopausal bone loss and the precision error (short-term in vivo measurement variability) in DXA-based BMD measurement.(1,22)

Our study has several limitations to be noted. First, we aimed to characterize the association between U-NTX measured during early postmenopause, but some participants did not have U-NTX measurements available until nearly 4 years after the FMP. Second, C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen in serum (S-CTX) is now recommended as the bone resorption marker of choice; however, SWAN, which started 20 years ago, measured U-NTX.(25) Additionally, urinary measures of bone turnover markers are more variable than serum measures,(26) which would reduce their accuracy in predicting bone loss rates. However, from a clinical standpoint, U-NTX has been recognized by some as more practical, with the suggestion that the measurement be repeated to reduce measurement error.(26) Third, we were unable to test the association between U-NTX in early postmenopause and incident fracture because the number of fractures subsequent to the date of U-NTX measurement is small in this middle-aged cohort. Fourth, with increased recognition that accumulated cortical bone loss after the MT exceeds that of trabecular bone over time, and that cortical bone contributes to fracture resistance,(27–29) it is important to be able to predict the rate of BMD decline at skeletal sites composed primarily of cortical bone, such as the distal radius; this data was not available in SWAN. However, in the early postmenopause, trabecular bone loss is thought to predominate, even at sites composed mostly of cortical bone.(30,31) Finally, specimen storage temperature at local sites during the 1-month period prior to shipment to Central Lab was not recorded in SWAN; we were therefore unable to adjust for this variable in our analyses.

In conclusion, this study confirms that higher levels of U-NTX measured in early postmenopause, following its MT-related rise, is most strongly associated with fast BMD decline across the MT. With the development of newer markers of bone turnover and novel technologies for assessing trabecular and cortical microarchitecture, future studies will determine the best bone turnover marker or best combination of turnover markers and the optimal thresholds needed to identify women at risk for rapid loss in bone mass and/or rapid deterioration in microarchitecture, and eventually develop and test the efficacy of early interventions for preventing bone loss and microarchitectural damage.

Acknowledgments

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’sHealth(ORWH) (Grants NR004061; AG012505, AG012535, AG012531, AG012539, AG012546, AG012553, AG012554, AG012495). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH. Additional support for this project provided by NIA through P30-AG028748; UCLA Claude Pepper Older Adults Independence Center (PI: David Reuben) funded by the National Institute of Aging (5P30AG028748); NIH/NCATS UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR000124; NIH Grant Number 5RO1AG033067 (PI: ASK and Carolyn Crandall). AS was supported by the UCLA Specialty Training and Advanced Research Program.

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor — Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 —present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994–2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA — Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999—present; Robert Neer, PI 1994–1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL — Howard Kravitz, PI 2009— present; Lynda Powell, P11994–2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser — Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles — Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY — Carol Derby, PI 2011-present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010–2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004–2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry — New Jersey Medical School, Newark — Gerson Weiss, PI 1994–2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA — Karen Matthews, PI. NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD — Winifred Rossi, 2012-present; Sherry Sherman, 1994–2012; Marcia Ory, 1994–2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD — Program Officers. Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor — Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services). Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA — Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012—present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001–2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA — Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995–2001. Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair; Chris Gallagher, Former Chair. We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Footnotes

Disclosures

JCL has received prior research funding from Amgen and current research funding from Sanofi Inc, unrelated to this study. AS, SI, GAG, JAC, and ASK state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ roles: AS: study concept and design; statistical analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, revision of manuscript. SI: study concept and design. GAG: study concept and design, drafting of manuscript; critical revision of manuscript; obtained funding; study supervision. JAC: drafting of manuscript; critical revision of manuscript. JCL: drafting of manuscript; critical revision of manuscript. ASK: study concept and design; statistical analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, critical revision of manuscript; study supervision.

References

- 1.Greendale GA, Sowers M, Han W, et al. Bone mineral density loss in relation to the final menstrual period in a multiethnic cohort: Results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(1):111–8. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sowers MR, Zheng H, Greendale GA, et al. Changes in bone resorption across the menopause transition: effects of reproductive hormones, body size, and ethnicity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(7):2854–63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Recker R, Lappe J, Davies K, Heaney R. Bone remodeling increases substantially in the years after menopause and remains increased in older osteoporosis patients. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(10):1628–33. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhter M, Lappe J, Davies K, Recker R. Transmenopausal changes in the trabecular bone structure. Bone. 2007;41(1):111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Neill T. The relationship between bone density and incident vertebral fracture in men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(12):2214–21. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Staa T, Dennison E, Leufkens H, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29(6):517–22. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaidi M, Turner C, Canalis E, et al. Bone loss or lost bone: rationale and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of early postmenopausal bone loss. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2009;7(4):118–26. doi: 10.1007/s11914-009-0021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dresner-Pollak R, Parker R, Poku M, Thompson J, Seibel M, Greenspan S. Biochemical markers of bone turnover reflect femoral bone loss in elderly women. Calcif Tissue Int. 1996;59(5):328–33. doi: 10.1007/s002239900135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Chapuy M, Delmas P. Increased bone turnover in late postmenopausal women is a major determinant of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(3):337–49. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers A, Hannon R, Eastell R. Biochemical markers as predictors of rates of bone loss after menopause. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(7):1398–404. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.7.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebeling P, Atley L, Guthrie J, et al. Bone turnover markers and bone density across the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(9):3366–71. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.9.8784098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings S, Black D, Rubin S. Lifetime risks of hip, Colles’,or vertebral fracture and coronary heart disease among white postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(11):2445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baecke J, Burema J, Frijters J. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:936–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenland S. Interpretation and choice of effect measures in epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125(5):761–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Štěpán J, Pospichal J, Presl J, Pacovskỳ V. Bone loss and biochemical indices of bone remodeling in surgically induced postmenopausal women. Bone. 1987;8(5):279–84. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(87)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Duboeuf F, Delmas P. Markers of bone turnover predict postmenopausal forearm bone loss over 4 years: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(9):1614–21. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.9.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Löfman O, Magnusson P, Toss G, Larsson L. Common biochemical markers of bone turnover predict future bone loss: a 5-year follow-up study. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;356(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer D, Sklarin P, Stone K, et al. Biochemical markers of bone turnover and prediction of hip bone loss in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(8):1404–10. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.8.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Greendale GA, et al. Bone resorption and fracture across the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2012;19(11):1200. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31825ae17e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Dieren S, Beulens W, Kengne A, et al. Prediction models for the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Heart. 2012;98(5):360–9. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buijsse B, Simmons R, Griffin S, Schulze M. Risk assessment tools for identifying individuals at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;95(2):299–307. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schousboe J, Shepherd J, Bilezikian J, Baim S. Executive Summary of the 2013 ISCD Position Development Conference on Bone Densitometry. J Clin Densitom. 2013;16(4):455–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szulc P, Delmas P. Biochemical markers of bone turnover: potential use in the investigation and management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(12):1683–704. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0660-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khosla S, Riggs B. Pathophysiology of age-related bone loss and osteoporosis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):1015–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasikaran S, Eastell R, Bruyère O, et al. Markers of bone turnover for the prediction of fracture risk and monitoring of osteoporosis treatment: a need for international reference standards. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(2):391–420. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naylor K, Eastell R. Bone turnover markers: use in osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(7):379–89. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szulc P, Seeman E, Duboeuf F, Sornay-Rendu E, Delmas P. Bone fragility: failure of periosteal apposition to compensate for increased endocortical resorption in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(12):1856–63. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanbhogue V, Brixen K, Hansen S. Age- and sex-related changes in bone microarchitecture and estimated strength. a three-year prospective study using HR-pQCT. J Bone Miner Res. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2817. Forthcoming. Epub 2016 Feb 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeman E. Age-and menopause-related bone loss compromise cortical and trabecular microstructure. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013 Oct;68(10):1218–25. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zebaze R, Ghasem-Zadeh A, Bohte A, et al. Intracortical remodelling and porosity in the distal radius and post-mortem femurs of women: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1729–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carnevale V, Dicembrino F, Frusciante V, Chiodini I, Minisola S, Scillitani A. Different patterns of global and regional skeletal uptake of 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate with age: relevance to the pathogenesis of bone loss. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1478–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]