Abstract

While urothelial signals, including sonic hedgehog (Shh), drive bladder mesenchyme differentiation, it is unclear which pathways within the mesenchyme are critical for its development. Studies have shown that fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (Fgfr2) is necessary for kidney and ureter mesenchymal development. Our objective was to determine the role of Fgfr2 in bladder mesenchyme. We used Tbx18cre mice to delete Fgfr2 in bladder mesenchyme (Fgfr2BM−/−). We performed three-dimensional reconstructions, quantitative real-time PCR, in situ hybridization, immunolabeling, ELISAs, immunoblotting, void stain on paper, ex vivo bladder sheet assays, and in vivo decerebrated cystometry. Compared with controls, embryonic (E) day 16.5 (E16.5) Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have thin muscle layers with reduced α-smooth muscle actin levels and thickened lamina propria with increased collagen expression that intrudes into muscle. From postnatal (P) day 1 (P1) to P30, Fgfr2BM−/− bladders demonstrate progressive muscle loss and increased collagen expression. Postnatal Fgfr2BM−/− bladder sheets exhibit decreased contractility and increased passive stretch tension compared with controls. In vivo cystometry revealed high baseline and threshold pressures and shortened intercontractile intervals in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders compared with controls. Mechanistically, while Shh expression appears normal, mRNA and protein readouts of hedgehog activity are increased in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders compared with controls. Moreover, E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders exhibit higher levels of Cdo and Boc, hedgehog coreceptors that enhance sensitivity to Shh, than controls. Fgfr2 is critical for bladder mesenchyme patterning by virtue of its role in modulation of hedgehog signaling.

Keywords: bladder development, bladder dysfunction, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2

murine bladder development begins at embryonic (E) day 10.5 (E10.5), when the cloaca is subdivided into the urogenital sinus ventrally and the anal canal dorsally (5). At E13.5, bladder urothelium induces the surrounding mesenchyme to begin differentiating into the inner lamina propria and outer smooth muscle layers (5). Secretion of sonic hedgehog (Shh) by bladder urothelium is a major inducer for mesenchymal patterning (5, 7, 8, 14, 15, 22). The E16.5 bladder begins receiving urine from the newly developed metanephric nephrons.

While fibroblast growth factor (Fgf) receptor (Fgfr) activity is critical for kidney development (11–13, 23–27, 33, 36), little is known about its role in bladder morphogenesis. Fgfrs are members of a family of four receptor tyrosine kinases with up to 22 Fgf ligands (18). While Fgf10 affects bladder urothelial cell patterning, no published data exist on Fgfr actions in developing bladder mesenchyme (10). While Fgfr2 is expressed in bladder urothelium and mesenchyme (13), its roles are unclear, as global Fgfr2 deletion results in early embryonic lethality (2).

Utilizing a Tbx18cre line to delete Fgfr2 in E10.5 peri-Wolffian duct stroma, we observed ureteric bud induction defects, abnormal ureteral insertion into the bladder, and high rates of postnatal vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) (33). More recently, we observed that the Tbx18cre line drove cre expression throughout E13.5 bladder mesenchyme. Closer inspection of embryonic and early postnatal mutants revealed previously unrecognized expansion of bladder lamina propria volume and reduction of detrusor muscle volume compared with littermate controls. In postnatal mice, muscle loss and fibrosis worsened, with correlative contractility defects, poor compliance, and voiding dysfunction. Mutant embryos had augmented hedgehog signaling, likely by derepression of expression of the hedgehog coreceptors cell adhesion molecule, downregulated by oncogenes (Cdo) and brother of Cdo (Boc).

METHODS

General.

A minimum of three control and mutant tissues/animals/samples (n) were used for each assay. The abnormal mutant phenotypes (where observed) were fully penetrant.

Mouse strains.

To visualize Tbx18cre expression in the developing bladder, we bred Tbx18creTg+ mice (gift from Feng Chen) (34) with Rosa-CAG-LSL-tdTomato-WPRE (CAG) reporter mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to generate mice that expressed red fluorescent protein in all cre-positive derivatives (Tbx18cre;CAG mice). Tbx18cre;Fgfr2Fl/Fl (Fgfr2BM−/−) mice were generated by breeding Tbx18creTg/+ mice with Fgfr2Lox/Lox mice (gift from David Ornitz) (35). All experiments were carried out with the approval of the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the guidelines of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Genotyping.

Genotyping was performed as described elsewhere (33). Briefly, after overnight digestion of embryonic tissues or tail clippings, DNA was precipitated and resuspended. PCR was then performed to detect the various alleles (see Table 1 for list of primer pairs).

Table 1.

Primers utilized for PCR genotyping

| Sequence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer | Size, bp | Forward | Reverse |

| Tbx18cre | 301 | 5′-CCATCCAACAGCACCTGGGCCAGCTCAACA-3′ | 5′-CCACCATCGGTGCGGGAGATGTCCTTCACT-3′ |

| Fgfr2 | |||

| WT | 307 | 5′-TTGACCGGATCTACACACACC-3′ | 5′-GTCAATTCTAAGCCACTGTCTGCC-3′ |

| Floxed | 373 | 5′-TTGACCGGATCTACACACACC-3′ | 5′-CTCCACTGATTACATCTAAAGAGC-3′ |

| tdTomato | |||

| Positive | 196 | 5′-CTGTTCCTGTACGGCATGG-3′ | 5′-GGCATTAAAGCAGCGTATCC-3′ |

| Negative | 297 | 5′-AAGGGAGCTGCAGTGGAGTA-3′ | 5′-CCGAAAATCTGTGGGAAGTC-3′ |

Three-dimensional reconstructions.

Three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions of E13.5, E16.5, and postnatal (P) day 1 (P1) bladder tissues were performed as described elsewhere (13). Briefly, paraffin-embedded control and Fgfr2BM−/− tissues were serially sectioned (embryonic tissues at 6 µm and postnatal tissues at 10 µm) through the entire bladder and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Individual images were projected to a monitor, and bladder layers were traced. Layers were stacked, and a 3D reconstruction was rendered (Stereo Investigator, MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT). Volumetric analyses (Neurolucida Explorer, MBF Bioscience) were performed on all reconstructed models (n = 4 per genotype).

In situ hybridization.

In situ hybridization was performed on 6-µm paraffin cross sections through the bladder of control and Fgfr2BM−/− embryos. Briefly, digoxigenin UTP-labeled antisense RNA probes were generated using a DIG RNA labeling kit (catalog no. 11175025910, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) against genes listed in Table 2. Hybridized probes were detected in sections via anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase Fab fragments (catalog no. 11093274910, Roche) and developed in BM purple (catalog no. 11442074001, Roche). Color reactions were stopped with double-distilled H2O, and sections were mounted with aqueous mounting medium and visualized.

Table 2.

List of in situ hybridization probe templates

| Gene | Accession No. |

|---|---|

| Bmp4 | NM_007554 |

| Gli1 | NM_010296 |

| Hhip | NM_020259 |

| Ptch1 | NM_008957 |

| Shh | NM_009170.3 |

Quantitative PCR.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed as described elsewhere (32). Briefly, Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladders (n = 6 per genotype) were collected, and RNA was extracted using a Mini-prep kit (catalog no. 74704, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). qPCR primers for α-smooth muscle actin (aSMA), collagen types Ia and IIIa (Col1a and Col3a), Shh, patched 1 (Ptch1), glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (Gli1), hedgehog-interacting protein (Hhip), bone morphogenetic protein 4 (Bmp4), myocardin (Myocd), growth arrest-specific protein 1 (Gas1), Boc, Cdo, and Gapdh (endogenous control) were designed using Primer3 software (29). SsoAdvanced universal SYBR Green Supermix (catalog no. 1725272, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was utilized on a real-time PCR system (ABI 7900 HT, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to detect mRNA expression levels.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

For histology, paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 6 µm and stained with H&E or Masson’s trichrome (to stain for collagen). For immunohistochemistry, paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed, antigen was retrieved, and sections were blocked and incubated overnight with antibodies against αSMA (1:250 dilution; catalog no. A5528, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), Col1a (1:250 dilution; catalog no. 1310-01, SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL), or Col3a (1:250 dilution; catalog no. 1330-01, SouthernBiotech) at 4°C. Sections were then washed and incubated with secondary antibodies [rabbit anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500 dilution; catalog no. A-21205, Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY) or sheep anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500 dilution; catalog no. A-11055, Molecular Probes)] and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:10,000 dilution; catalog no. D9542, Sigma Aldrich). Sections were then washed, mounted, and visualized.

Apoptosis, proliferation, and cell counting.

Proliferating cells were identified by immunohistochemistry using primary antibodies against phosphorylated histone H3 (1:200 dilution; catalog no. 9701, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and secondary sheep anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500 dilution) antibodies and DAPI (1:10,000 dilution) as described above. For each assay, immunohistochemistry was performed on cross sections through the dome, midpoint, and neck regions of each E16.5 bladder. After sections were stained, the mean value for all sections in a single bladder was used to generate a representative value for each bladder per genotype (n = 4 per genotype). To identify apoptotic cells, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue sections using an ApopTag Fluorescein Direct In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (catalog no. S7160, EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (in cross sections similar to those used to determine proliferation). DAPI-positive nuclei within the lamina propria were also counted in cross sections through the dome, midpoint, and neck regions of each E16.5 bladder. Apoptosis, proliferation (n = 4 samples per genotype per assay), and number of lamina propria cells (cells/area) were quantified (n = 3 samples per genotype per assay) using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Western blotting.

Protein samples (30 μg each) from whole embryonic and postnatal bladders were resolved in 8% SDS-Tris gels (catalog no. 161-0732, Bio-Rad). Proteins were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes (catalog no. 162-0115, Bio-Rad), blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies [αSMA (1:2,000 dilution; Sigma Aldrich); Gli1 (1:1,000 dilution; catalog no. 2534, Cell Signaling Technology), and α/β-tubulin (1:1,000 dilution; catalog no. 2148, Cell Signaling Technology)]. Membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 and probed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies [1:2,000 dilution: anti-mouse-HRP (catalog no. 7074) and anti-rabbit-HRP (catalog no. 7076, Cell Signaling Technology)]. Bound antibodies were visualized using the Amersham ECL Prime Western blot detection kit (catalog no. RPN2232GE, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Total collagen detection.

E16.5 and P1 control and Fgfr2BM−/− bladders (n = 8 samples per genotype) were homogenized in 1 mg/ml pepsin in 0.05 M acetic acid and then incubated in the solution for 48 h at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected, and collagen concentration was detected with the Sirius red collagen detection kit (catalog no. 9062, Chondrex, Redmond, WA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Void stain on paper.

P30 control and Fgfr2BM−/− mice (n = 8–10 per genotype) were placed individually in metabolic cages lined with Whatman paper and allowed ad libitum access to food and water for 4 h. Then the mice were returned to their home cages, and Whatman papers were collected and urine stains were photographed using a UV light box. All images were subsequently analyzed using ImageJ software.

Bladder sheet assays.

Bladder sheet assays were performed as described elsewhere (16). Briefly, bladders were dissected from male control and Fgfr2BM−/− mice (n = 3 per genotype) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in Ca2+-free Tyrode solution. Then the bladders were cut along the dorsal aspect to form a sheet. The sheets were pinned to the fixed platform (with the mucosal surface facing up) in the recording chamber, with the dome tied to a stainless steel bar connected to a tension transducer. Contractile activity was measured through a tension transducer attached to an oil hydraulic micromanipulator (Narishige, East Meadow, NY) and computer-controlled through a stepper motor to allow precise increments of stretch. The recording chambers were placed on a Peltier block (University of Pittsburgh machine and electronics shops) to maintain the temperature at 37 ± 0.5°C and superfused with Tyrode solution at a rate of 1 ml/min. Bladder sheets were stretched to 1 g of resting tension, and all preparations were allowed to equilibrate for ≥30 min.

For agonist treatment, α,β-methylene ATP and carbachol were added to equilibrated bladder sheets at physiological concentrations, with the force contraction of the bladder recorded following administration. Bladders were then washed and returned to equilibrium before agonist administration. For electrical field stimulation, equilibrated bladder sheets were stimulated at 30-s intervals with increasing electrical frequency ranging from 8 to 20 Hz. Contractile responses of bladders following each stimulation were recorded as outlined elsewhere (16).

In vivo cystometry.

P30 control and Fgfr2BM−/− male mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and intubated via a small incision using PE-60 tubing. The skull was exposed, and the forepart to the lambdoid suture was removed. The brain stem was sectioned at the supracollicular level, tissues rostral to the section were withdrawn, and anesthesia was discontinued. After supracollicular decerebration, the bladder was exposed via a midline abdominal incision. A flanged PE-50 catheter was passed through a small opening at the apex of the bladder dome and secured with suture. The catheter was connected by a three-way stopcock to an infusion pump (PUMP 33, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) and a pressure transducer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) joined to a transbridge (model TBM4M, World Precision Instruments). For intravesical pressure recordings, saline (25°C) was continuously infused at a constant rate of 0.01 ml/min. Mice were observed for voiding, and voiding contractions were noted.

Statistics.

Student’s t-tests were conducted where appropriate using GraphPad Prism 5 (1992–2007, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Fgfr2 is deleted in E13.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder mesenchyme.

In comparison with adjacent H&E-stained sections, E13.5 Tbx18cre;CAG bladders expressed red fluorescent protein in bladder mesenchyme, but not urothelium (Fig. 1, A and B). Moreover, while in situ hybridization revealed Fgfr2 mRNA expression in both the urothelium and mesenchyme in E13.5 controls, selective loss of Fgfr2 was observed in bladder mesenchyme in E13.5 Fgfr2BM−/− mice (Fig. 1, C and D). In E16.5 control and Fgfr2BM−/− bladders, immunoblotting illustrated reduced phosphorylation of Erk1/2, downstream effectors of Fgfr signaling in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders (likely reflecting the selective loss of Fgfr2 signaling in the mesenchyme) (Fig. 1E). Thus, Fgfr2 expression and signaling appear to be deleted in bladder mesenchyme of Fgfr2BM−/− mice.

Fig. 1.

Tbx18cre drives fibroblast growth factor (Fgf) receptor 2 (Fgfr2) deletion in developing bladder mesenchyme. A: hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E)-stained cross section of a Tbx18cre;CAG bladder at embryonic (E) day 13.5 (E13.5). B: fluorescence image from a section adjacent to A illustrates red fluorescent protein (cre) expression in bladder mesenchyme, but not urothelium. C and D: in situ hybridization for Fgfr2 shows expression in bladder mesenchyme (arrowhead) and urothelial tissue layers (arrow) in control bladder, but not mesenchyme, of Fgfr2BM−/− bladder. Dotted lines indicate outer boundary of developing bladder. *, Bladder lumen; BM, bladder mesenchyme; U, urothelium; UA, umbilical artery. Scale bars = 150 μm. E: Western blot demonstrates reduced Erk1/2 phosphorylation (pErk1/2) with comparable total Erk1/2 (tErk1/2) in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− vs. age-matched control bladder (cropped blots are shown as indicated by lines; these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). a/b-Tubulin, α/β-tubulin loading control.

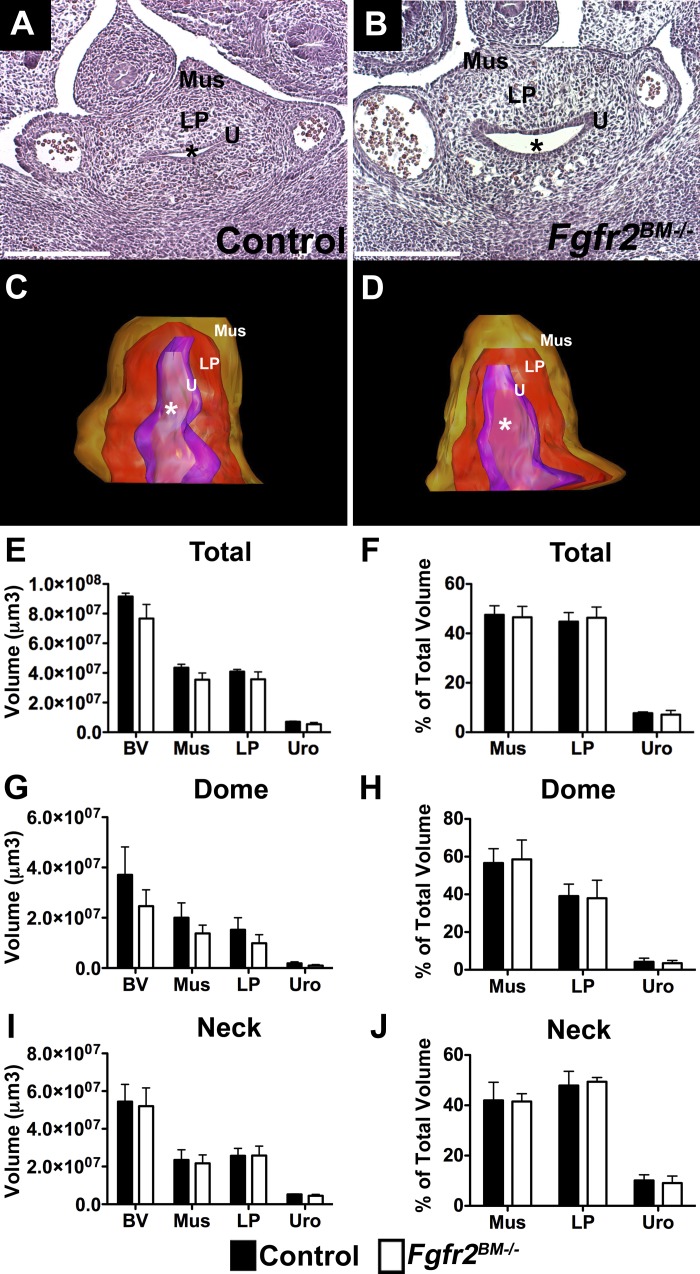

Tissue volumes and composition are altered in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders.

While the Tbx18cre line is known to drive cre expression in tissues outside the bladder, including ureter mesenchyme, heart, limb, and vibrissae (34), we noted no overt defects in these tissues in Tbx18cre;Fgfr2Fl/Fl embryonic or postnatal mice. Histological analysis and 3D reconstructions of total bladders also revealed no apparent differences between E13.5 control and Fgfr2BM−/− bladders (Fig. 2, A–F). Given that bladder muscle development starts at the top of the bladder dome and extends gradually to the neck region, we also performed 3D analysis of the “dome” half and the “neck” half of the developing bladders separately. As was true for total bladder, we observed no differences between E13.5 control and Fgfr2BM−/− bladder dome and neck tissue composition or volume (Fig. 2, G–J). By E16.5, however, H&E staining showed regions of thin detrusor muscle and thickened lamina propria in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders compared with age-matched controls (Fig. 3, A and B). Furthermore, while 3D reconstructions revealed no differences in total bladder and urothelial mean volumes in E16.5 mutants, the mean volume of lamina propria was increased compared with controls (Fig. 3, C–F). Also, a statistical increase in lamina propria tissue volume in bladder dome regions and a significant decrease in smooth muscle volume in neck regions were observed in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− muscle compared with age-matched controls (Fig. 3, G and I). Finally, as a percentage of total, dome, and neck bladder volume, E16.5 mutant muscle was decreased, lamina propria increased, and urothelium unchanged compared with controls (Fig. 3, H and J).

Fig. 2.

E13.5 control and Fgfr2BM−/− bladders appear comparable. A and B: H&E-stained sections from E13.5 control and Fgfr2BM−/− bladders demonstrate similar histology. Scale bars = 150 μm. C and D: 3-dimensional (3D) reconstructions reveal similar-appearing urothelial volume (purple), lamina propria volume (red), and muscle volume (brown) in E13.5 Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladders. *, Lumen; U, urothelium; LP, lamina propria; Mus, muscle. E: quantification of 3D bladder reconstructions confirms comparable total bladder volume (BV) and muscle (Mus), lamina propria (LP), and urothelial (Uro) mean volumes in E13.5 controls and mutants. F: when normalized to total bladder volumes, mean muscle, lamina propria, and urothelial volume percentages are comparable in E13.5 Fgfr2BM−/− and age-matched control bladders. G and H: graphs of 3D bladder “dome” reconstructions confirm comparable bladder, muscle, lamina propria, and urothelial mean volumes and normalized dome muscle, lamina propria, and urothelial volume percentages in E13.5 controls and mutants. I and J: graphs of 3D bladder neck reconstructions confirm comparable bladder, muscle, lamina propria, and urothelial mean volumes and normalized neck muscle, lamina propria, and urothelial volume percentages in E13.5 controls and mutants. Values are means ± SD.

Fig. 3.

E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have reduced muscle and increased lamina propria. A and B: representative H&E-stained E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder section appears to have thinner muscle regions (arrowheads) and an expanded lamina propria compared with age-matched control. Scale bars = 300 μm. C and D: 3D reconstructions appear to show an expanded volume of lamina propria (red) and reduced volume of muscle (brown) in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder compared with control. *, Lumen; U, urothelium; LP, lamina propria; Mus, muscle. E: graph of 3D bladder reconstructions illustrates comparable total bladder (BV), muscle (Mus), and urothelial (Uro) mean volumes in E16.5 mutants and controls but a significant increase in lamina propria (LP) mean volume in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. F: when normalized to total bladder volume, mean muscle volume percentage is reduced, lamina propria percentage is increased, and urothelial percentage is equivalent in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. G: graph of 3D bladder dome reconstructions illustrates comparable bladder, muscle, and urothelial mean volumes in E16.5 mutants and controls but a significant increase in lamina propria mean volume in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. H: when normalized to bladder dome volume, mean muscle volume percentage is reduced, lamina propria percentage is increased, and urothelial percentage is equivalent in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. I: graph of 3D bladder neck reconstructions illustrates comparable bladder, lamina propria, and urothelial mean volumes in E16.5 mutants and controls but a significant decrease in muscle mean volume in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. J: when normalized to bladder neck volume, mean muscle volume percentage is reduced, lamina propria percentage is increased, and urothelial percentage is equivalent in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Values are means ± SD.

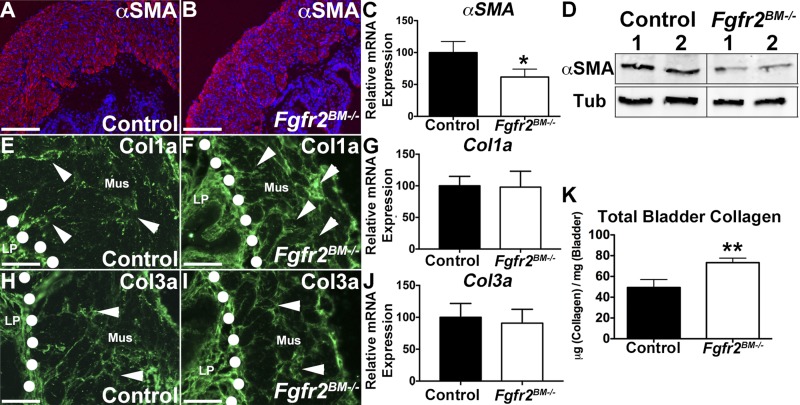

We then interrogated whether bladder composition was altered in E16.5 mutants. Immunolabeling revealed robust αSMA staining in outer mesenchymal layers of controls but less intense regional staining in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders (Fig. 4, A and B). While αSMA mRNA levels appeared equivalent between mutants and age-matched controls by qPCR (Fig. 4C), Western blots confirmed reduced αSMA protein levels in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders compared with controls (Fig. 4D). Col1a and Col3a immunolabeling revealed more intense signal in E16.5 mutant than control lamina propria (Fig. 4, E, F, H, and I). Furthermore, collagen fibril infiltration into the muscle layer was observed in Fgfr2BM−/−, but not control, bladders. Real-time PCR and collagen ELISAs confirmed increases in Fgfr2BM−/− bladder collagen mRNA and protein (Fig. 4, G, J, and K). Real-time PCR analysis for Myocd, a gene critical for initiation of smooth muscle development (8), showed no changes in E16.5 mutant compared with control expression (mean mutant expression 96.6% of control, n = 6, P > 0.05); thus an interruption in mutant bladder muscle differentiation is unlikely. Muscle and lamina propria are mispatterned in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders compared with controls.

Fig. 4.

E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have decreased smooth muscle and increased collagen levels. A and B: representative α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) immunofluorescence (red, arrows) reveals regions of thinner muscle in Fgfr2BM−/− (arrowheads) than control bladder. Blue, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear staining. C: quantitative PCR (qPCR) shows equivalent αSMA mRNA expression in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladders. D: Western blot demonstrates reduced αSMA protein expression in whole E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladder (cropped blots are shown as indicated by lines; these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). Tub, α/β-tubulin loading control. E and F: representative collagen type Ia (Col1a) immunofluorescence (green) reveals more intense staining in lamina propria (below dotted lines) and regions of collagen infiltration in smooth muscle layer (arrowheads) of E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− than control bladder. G: qPCR illustrates significantly increased Col1a mRNA expression in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control whole bladders. H and I: collagen type IIIa (Col3a) immunofluorescence illustrates brighter staining (below dotted lines) and collagen infiltration into smooth muscle layer (arrowheads) of E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladder. J: qPCR illustrates significantly increased Col3a mRNA expression in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. K: graph showing increased collagen protein by ELISAs in whole E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder lysates compared with age-matched controls. Scale bars = 300 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Values are means ± SD.

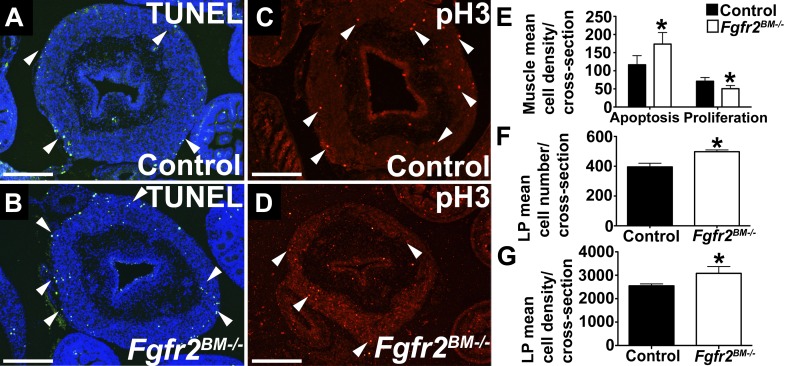

E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have increased muscle apoptosis, decreased muscle cell proliferation, and increased number of lamina propria cells.

We then determined whether the changes in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder tissue volume were due to alterations in apoptosis or proliferation. While mutant lamina propria and urothelium had similar low levels of apoptosis compared with controls (Fig. 5, A and B, and data not shown), the number of apoptotic cells was significantly increased in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder muscle compared with age-matched controls (Fig. 5, A, B, and E). Conversely, while bladder lamina propria and urothelial proliferation rates were similar in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladder tissue (Fig. 5, C and D, and data not shown), cell proliferation was significantly decreased in mutant muscle compared with age-matched controls (Fig. 5, C–E). While we did not observe changes in rates of lamina propria apoptosis or proliferation between genotypes, both mean number of lamina propria cells per cross section and mean cell density within the lamina propria were significantly increased in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders compared with age-matched controls (Fig. 5, F and G). Thus, in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders, apoptosis and proliferation are perturbed within the developing muscle layer, and not within urothelial or lamina propria tissues. However, total number of cells and cell density are increased in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder lamina propria compared with controls.

Fig. 5.

E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have increased muscle apoptosis, decreased muscle cell proliferation, and increased number of lamina propria cells. A and B: representative bladder cross sections reveal more TUNEL-positive cells (green, arrowheads) in mutant than control detrusor muscle layer, with little staining in mutant and control lamina propria and urothelium. Blue, DAPI nuclear staining. C and D: representative bladder cross sections illustrate decreased phosphorylated histone H3 (pH3)-positive proliferating cells (red, arrowheads) in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− muscle layers compared with control, with minimal staining in mutant and control lamina propria and urothelium. Scale bars = 300 µm. E: increased apoptosis and decreased cell proliferation in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders. F and G: increased mean number of cells and mean cell density per cross section within lamina propria (LP, cells/mm2) in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders. *P < 0.05. Values are means ± SD.

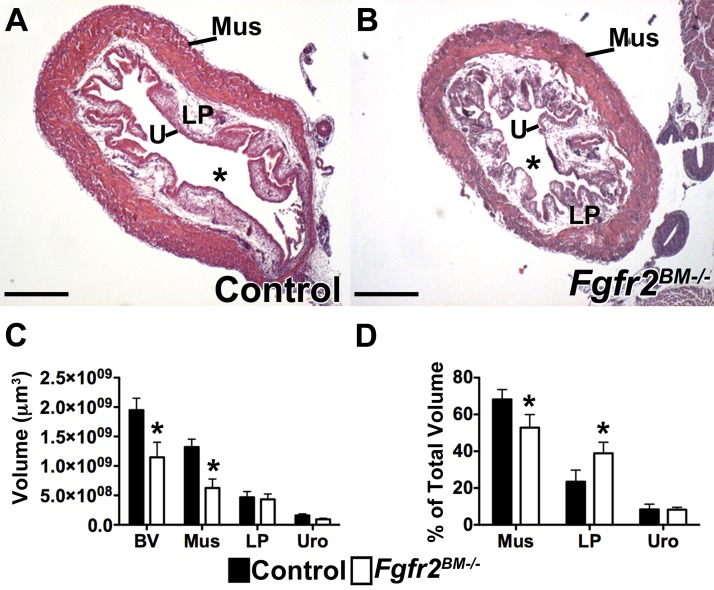

Postnatal Fgfr2BM−/− mice have perturbations in bladder lamina propria and muscle.

P1 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders appear smaller, with regional muscle thinning (Fig. 6, A and B). 3D reconstructions confirm that mean Fgfr2BM−/− total bladder and bladder muscle volumes are reduced compared with controls (Fig. 6, C and D). Also, as a percentage of total bladder volume, P1 mutant muscle was decreased, mutant lamina propria increased, and urothelium unchanged compared with controls (Fig. 6, C and D). Immunostaining, qPCR, and Western blots revealed reduced αSMA expression in P1 mutant bladder muscle compared with controls (Fig. 7, A–D). ELISA of total bladder collagen at this stage did reveal increases in mutant protein compared with controls (Fig. 7K). While qPCR did not reveal significant differences in Col1a mRNA, immunofluorescence revealed more apparent Col1a infiltration in mutant than control muscle (Fig. 7, E–G). Col3a qPCR and staining were not notably different between mutants and controls (Fig. 7, H–J). Thus, bladder collagen protein is increased in P1 mutant bladders, although the collagen subtype(s) are not entirely clear.

Fig. 6.

Postnatal (P) day 1 (P1) Fgfr2BM−/− bladders are smaller, with muscle and lamina propria mispatterning. A and B: representative H&E-stained sections reveal a decrease in bladder size and regions of thin muscle in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladder. *, Lumen; U, urothelium; LP, lamina propria; Mus, muscle. Scale bars = 500 μm. C: graph of 3D bladder reconstructions demonstrates significant reductions in total bladder volume (BV) and muscle volume (Mus) in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders. D: when normalized to total bladder volumes, mean muscle (Mus) percentage is reduced, lamina propria (LP) percentage is increased, and urothelial (Uro) percentage is equivalent in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders. *P < 0.05. Values are means ± SD.

Fig. 7.

P1 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have decreased smooth muscle and increased collagen. A and B: representative αSMA immunostaining (red) appears less compact in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− than control bladder. Blue, DAPI nuclear staining. C: qPCR illustrates reduced aSMA mRNA expression in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladder. D: Western blot demonstrates reduced αSMA protein in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders (cropped blots are shown as indicated by lines; these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). Tub, α/β-tubulin loading control. E and F: Col1a immunolabeling (green) reveals regions of apparently increased collagen deposition (arrowheads) in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladder muscle layer. G: qPCR illustrates equivalent Col1a mRNA expression in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladders. H and I: Col3a immunostaining (green, arrowheads) appears similar in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladder smooth muscle layers. J: qPCR illustrates equivalent Col3a mRNA expression in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladders. K: increased collagen protein in whole P1 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladder lysates. In E, F, H, and I, dotted lines represent boundary of lamina propria and smooth muscle layer. Scale bars = 300 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Values are means ± SD.

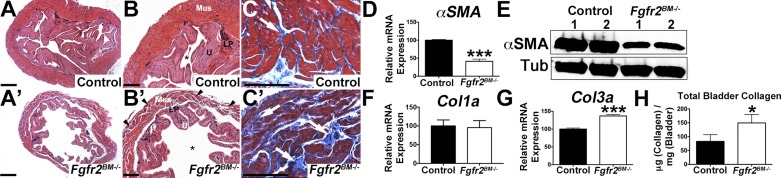

P30 control and Fgfr2BM−/− bladders were similar in overall size; however, bladder walls were markedly thinner in the mutants, resulting in larger lumens in Fgfr2BM−/− than control bladders (Fig. 8, A and B). Trichrome staining also illustrated extensive collagen infiltration in the mutant detrusor layer relative to controls (Fig. 8C). qPCR and Western blot analysis revealed much less αSMA mRNA and protein in P30 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders than controls, consistent with loss of mutant muscle (Fig. 8, D and E). qPCR revealed equivalent Col1a mRNA in mutants and controls (Fig. 8F) but increased Col3a mRNA in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders (Fig. 8G). Finally, ELISAs demonstrated more collagen protein in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders than controls, consistent with the fibrosis revealed by trichrome and Picrosirius red staining (Fig. 8H).

Fig. 8.

P30 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have reduced muscle and increased collagen. A, A′, B, and B′: representative H&E staining illustrates thinner and less compact muscle layer in P30 Fgfr2BM−/− (arrowheads) than age-matched control bladder. *, Lumen; U, urothelium; LP, lamina propria; Mus, muscle. C and C′: trichrome staining shows increased collagen deposition (blue stain) in detrusor layer of P1 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladder. Scale bars = 700 μm (A and A′), 500 μm (B and B′), and 300 μm (C and C′). D: qPCR illustrates significantly reduced aSMA mRNA expression in P30 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. E: Western blot demonstrates reduced αSMA protein in P30 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders (cropped blots are shown as indicated by lines; these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). Tub, α/β-tubulin loading control. F and G: qPCR illustrates equivalent Col1a in P30 Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladders and increased Col3a mRNA expression in P30 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders. H: graph of ELISAs showing increased collagen in whole P30 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladder lysates. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Values are means ± SD.

Postnatal Fgfr2BM−/− mice develop significant bladder dysfunction.

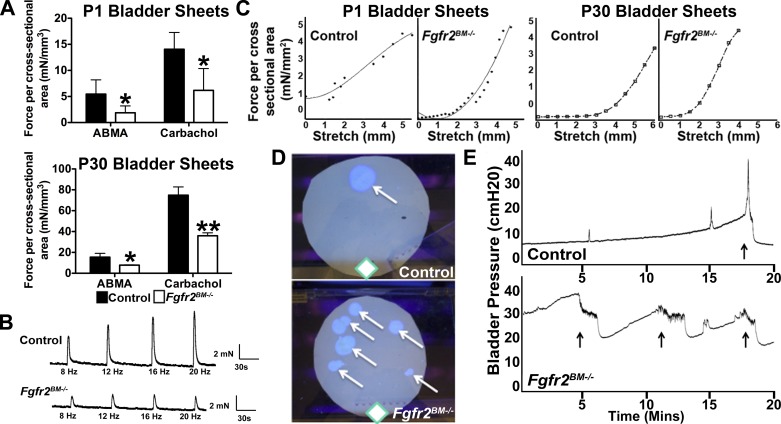

To evaluate functional defects in P1 and P30 Fgfr2BM−/− mice, we first performed assays in isolated bladder sheets. Stimulation with α,β-methylene ATP (a purinergic agonist) or carbachol (a muscarinic agonist) elicited a marked reduction in Fgfr2BM−/− bladder sheet contractile response compared with controls at both ages (Fig. 9A). Electrical field stimulation revealed no differences in P1 mutants compared with controls (data not shown), whereas contractile responses were attenuated in P30 mutants (Fig. 9B). With passive stretch, tension was increased (leftward shift of the curves) in P1 and P30 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder sheets compared with controls, indicating decreased compliance (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 9.

Fgfr2BM−/− mice have bladder and voiding dysfunction. A: ex vivo bladder sheets from P1 and P30 Fgfr2BM−/− mice exhibit attenuated contractile force generation when stimulated via α,β-methylene ATP (ABMA, purinergic) or carbachol (muscarinic) agonists compared with age-matched controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Values are means ± SD. B: representative electrical field stimulation profiles of P30 bladder sheets demonstrate attenuated responses to all frequencies in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders. C: passive tension profiles in response to stretch show a leftward shift in P1 and P30 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladder sheets. D: representative void-stain-on-paper assays from P30 control and Fgfr2BM−/− mice illustrate differences in frequency and location of voids (arrows) relative to sources of food and water (◇) within the cage. E: representative 20-min in vivo cystometry traces indicate higher baseline and threshold pressures and shortened intercontraction intervals in P30 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control mouse. Arrows, voiding responses.

We then performed in vivo functional analyses in P30 mice. First, void-stain-on-paper assays revealed that control mice exhibited fewer (4.14 ± 1.86) void stains distant from the food and water supply, while Fgfr2BM−/− mice averaged many more (7.83 ± 3.06) void spots (P < 0.05) throughout their enclosure (Fig. 9D). Second, cystometry in decerebrated, live mice illustrated higher baseline and threshold pressures and shortened intercontraction intervals in Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders (Fig. 9E). Thus the bladder mispatterning led to reduced agonist-induced muscle contraction, increased tension/poor compliance, high pressures, and abnormal voiding patterns in Fgfr2BM−/− mice compared with controls.

Fgfr2BM−/− mice have no evidence of bladder outlet obstruction.

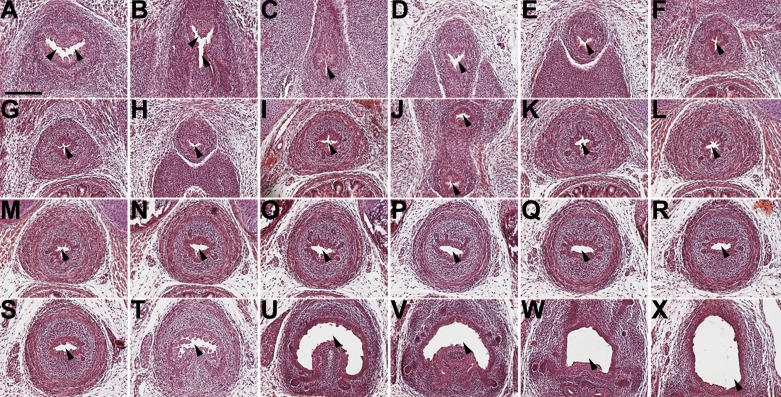

To determine if Fgfr2BM−/− mice had urethral obstruction, we serially sectioned from the bladder to the end of the urethra of E14.5 and P1 Fgfr2BM−/− male mice. The urethra was patent throughout its length at both ages (Fig. 10, and not shown). Also, no red fluorescent protein (cre) was expressed in urethral epithelium or surrounding tissue of Tbx18creTg/+; CAG mice (not shown); thus, Fgfr2 expression would not be perturbed in Fgfr2BM−/− urethras.

Fig. 10.

P1 Fgfr2BM−/− mice have no urethral obstruction. H&E-stained serial sections from most distal (A) to proximal (X) portion of urethra in P1 Fgfr2BM−/− male show lumen (arrowheads) at all levels with no evidence of obstruction. Scale bar = 150 µm.

Shh signaling is inappropriately unregulated in embryonic Fgfr2BM−/− bladders.

At E13.5, in situ hybridization and qPCR revealed no changes in Shh or hedgehog target gene expression in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders (not shown). At E16.5, Shh expression still appears similar in mutant and control urothelium by in situ hybridization; however, expression of multiple hedgehog readouts, including Ptch1, Hhip, and Bmp4 in the lamina propria and Gli1 in the lamina propria and muscle layer, appears increased in Fgfr2BM−/− mesenchyme (Fig. 11, A–E). Moreover, qPCR confirms no change in Shh but increases in all readouts in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders compared with controls (Fig. 11F). Additionally, Western blots also show increased Gli1 protein expression in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders compared with controls (Fig. 11G), confirming augmented Shh activity in mutant bladders (even though Shh levels are unchanged).

Fig. 11.

E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have augmented sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling. A and A′: in situ hybridization reveals comparable urothelial Shh mRNA expression (arrowheads) in E16.5 control and Fgfr2BM−/− bladders. B, B′, C, C′, D, and D′: in situ hybridization reveals more intense Ptch1, Hhip, and Bmp4 mRNA expression (arrowheads) in suburothelial lamina propria in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− (B′–D′) than age-matched control (B–D) bladders. E and E′: Gli1 mRNA expression is more robust in suburothelial (arrowheads) and muscle (arrows) layers in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− than control bladder. Scale bars = 300 μm. F: qPCR confirms no change in Shh mRNA but increased expression of hedgehog readouts, Ptch1, Hhip, Bmp4, and Gli1, in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with control bladders. G: Western blot illustrates increased Gli1 protein in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladder (cropped blots are shown as indicated by lines; these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). Tub, α/β-tubulin loading control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Values are means ± SD.

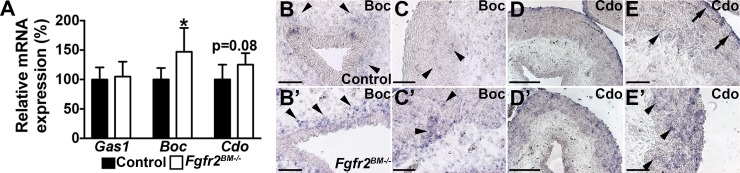

Shh signaling can be enhanced by ectopic expression of the cell surface coreceptors Boc and Cdo, with no changes in Shh levels (1). While qPCR revealed equivalent Gas1 expression in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− and control bladders, Fgfr2BM−/− bladders exhibited increased Boc and a trend for increased Cdo levels compared with controls (Fig. 12A). In situ hybridization revealed increased Boc expression in mutant periurothelial lamina propria and in muscle adjacent to the lamina propria compared with controls (Fig. 12, B and C). Cdo expression in E16.5 control bladders was restricted to the muscle adjacent to the lamina propria and the outer serosa, while Cdo expression in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders was stronger and diffuse throughout the smooth muscle layer (Fig. 12, D and E). Thus it is likely that the increases in mutant Shh activity are mediated by increases in Boc and Cdo expression in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder mesenchyme.

Fig. 12.

E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladders have increased Boc and Cdo expression. A: qPCR illustrates comparable Gas1 mRNA expression but elevated Boc and trends for elevated Cdo mRNA expression in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladders. B, B′, C, and C′: in situ hybridization reveals more intense Boc expression in suburothelial (arrowheads) and muscle layers adjacent to lamina propria (arrows) in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− (B′ and C′) than control (B and C) bladders. D, D′, E, and E′: in situ hybridization reveals that Cdo mRNA expression is confined to muscle adjacent to lamina propria (arrowheads) and outer serosal layer (arrows) of E16.5 control bladder (D and E), whereas in the E16.5 mutant (D’ and E’), it is strongly expressed throughout the entire muscle layer (concave arrowheads) up to the serosal layer. *P < 0.05. Values are means ± SD. Scale bars = 150 μm (B, B′, C, C′, E, and E′) and 300 μm (D and D′).

DISCUSSION

In a previous publication in which the Tbx18cre line was utilized to delete Fgfr2, we focused on how loss of the receptor in E10.5 peri-Wolffian duct stroma led to ureteric bud induction defects, abnormal ureteral insertion into the bladder, and high rates of postnatal VUR (33). For that study, we aged the mice to P1 and did not systematically examine the bladders for structural defects (other than to note that mutants did develop a relatively “normal”-appearing lamina propria and muscle layer based on H&E staining). Subsequent to that study, we noted obvious bladder histological defects that could not be explained by ureteric induction defects and reflux in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders in mutant mice to P30. Thus, based on known expression of Tbx18 in bladder mesenchyme as early as E13.5 (http://www.gudmap.org), we first confirmed that the Tbx18cre line was expressed in and was able to delete Fgfr2 in bladder mesenchyme (Fig. 1). We then began a systematic assessment of structural and functional bladder defects in the Tbx18cre;Fgfr2Fl/Fl mice. We ultimately noted that there were indeed changes in mutant E16.5 and early postnatal bladder mesenchyme tissue volumes and composition that had dramatic structural and functional consequences in older postnatal mice.

To our knowledge, Fgfr2 is only the third known signaling pathway, outside Shh and Tgfß superfamily signaling, that is critical for bladder mesenchyme patterning (5, 7, 8, 14, 15, 17, 22). Groundbreaking studies from Yamada’s laboratory documented temporal expression patterns of Shh in early urothelium of the cloaca that continued in the early bladder and urethra, signaling to adjacent mesenchyme in these structures (15). Studies in the laboratories of Yamada and Baskin also showed how mesenchyme patterning, including muscle formation, is clearly dependent on Shh expression and signaling emanating from the urothelium (5, 7, 14, 15, 22). Interestingly, previous studies have also indicated that both Shh and Tgfß signaling families (in particular, Bmp4) are tightly associated (20, 22). While Shh signaling has been shown to modulate smooth muscle differentiation directly, Shh can also regulate the expression of Bmp4, a factor itself capable of inducing smooth muscle patterning (6, 14, 15, 28). In our current study we demonstrate that Shh signaling activity and Bmp4 expression are concurrently increased in Fgfr2BM−/− bladder mesenchyme, suggesting two possible mechanisms for altered bladder patterning in our mice.

The alterations in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− bladder patterning could be due to a combination of decreased cell survival, reduced proliferation, and altered cell fate determination. Indeed, TUNEL and phosphorylated histone H3 staining clearly show excessive apoptosis and decreased proliferation in E16.5 Fgfr2BM−/− compared with age-matched control bladder muscle layers, accounting, at least in part, for the reduction in muscle. However, the magnitude of these changes may not fully account for the degree of smooth muscle reduction in mutant bladders. Furthermore, Fgfr2BM−/− lamina propria proliferation and apoptosis rates are equivalent to controls, yet total number of cells per cross section and cell density within the lamina propria are significantly increased, indicating that there must be another explanation, such as altered cell determination, for the expanded mutant lamina propria. Indeed, others have shown that hedgehog concentration determines cell determination in embryonic bladder mesenchyme (4). Cao et al. showed that culturing fetal urothelium next to intact E13.5 bladders converts the adjacent putative muscle layer to a nonmuscle (i.e., “lamina propria”) fate (4). Furthermore, coculture of isolated embryonic bladder mesenchyme with fetal esophagus, which has very high Shh levels, induces a larger zone of muscle inhibition and a thinner outer muscle layer than coculture with other Shh-expressing epithelia (4). Thus it follows that the enhanced Shh activity in Fgfr2BM−/− bladder mesenchyme likely contributes to an alteration of mesenchymal patterning, such that some of the putative muscle cells instead became lamina propria cells. Together, a change in cell fate determination and perturbed muscle apoptosis and proliferation likely lead to the observed increase in Fgfr2BM−/− lamina propria and decrease in muscle layer volumes compared with controls.

The means by which Fgfr2 represses Shh activity (and Bmp4 expression) in embryonic bladder appears novel, namely, by dampening Boc and Cdo levels. Recent studies have shown that ectopic Boc and/or Cdo expression alone augments the Shh activity (1). Furthermore, Cdo is required for esophageal smooth muscle morphogenesis and orientation (21). Moreover, while a Shh signaling feedback loop may regulate Boc and Cdo levels, there are no published data on other genes or signaling pathways that limit Cdo or Boc expression (1). Thus, directly or indirectly, Fgfr2 appears to repress Cdo and Boc levels in the bladder. This adds a new dimension to the existing work done by other laboratories, including those of Baskin, Yamada, and McHugh (5, 7, 8, 14, 15, 22), about how short- and long-range Shh signaling patterns bladder mesenchyme, including lamina propria and muscle, respectively. This novel means of modulating hedgehog signaling may be relevant in other developing systems in which Fgf and Shh signaling interact.

The reduced bladder muscle volume and expanded lamina propria in Fgfr2BM−/− bladders result in significant structural and functional changes postnatally. The muscle loss likely leads to the decreased contractility, while the increased collagen content likely leads to the poor compliance and high pressures seen in functional assays. Another study showed that an increase in total collagen and a reduction in the smooth muscle-to-connective tissue ratio were strongly associated with bladder dysfunction and a reduction in bladder wall elasticity in humans (19). It is unclear why qPCR showed equivalent bladder Col1a and Col3a at P1 (despite mutant total collagen levels having been increased); however, by P30, mutant Col3a mRNA and total collagen protein were increased compared with controls, while Col1a was unchanged. An increase in the Col3-to-collagen ratio and an absolute increase in Col3 reportedly occur with age in pediatric patients with neurogenic bladders (9).

Clinical studies have shown that 30–40% of patients (namely, children) with bladder dysfunction also exhibit VUR (30, 31). In these patients, the risk of developing chronic kidney disease and reflux nephropathy is greatly increased relative to patients with either VUR or bladder dysfunction alone (3). Despite the apparent association between VUR and bladder dysfunction, a genetic link between the two conditions has not been established. The Fgfr2BM−/− mouse model has both high rates of VUR (33) and significant bladder dysfunction, thus providing the first genetic link between the two conditions. It is possible that mutations in the FGF signaling pathway could drive lower urinary tract dysfunction and VUR in some patients with both conditions. Moreover, most children with dysfunctional voiding that present to pediatric urologists or nephrologists are typically thought to have psychosocial defects and not an underlying genetic predisposition. It is possible that permutations in FGF signaling may cause or exacerbate this clinical condition.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01 DK-104374 (C. M. Bates) and P01 DK-093424 (A. Kanai) and Grant P30 DK-079307 to the Pittsburgh Center for Kidney Research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.I., I.Z., C.M.S., and D.S.B. performed experiments; Y.I., I.Z., C.M.S., W.C.d.G., A.J.K., and C.M.B. analyzed data; Y.I., I.Z., and C.M.B. prepared figures; W.C.d.G., A.J.K., and C.M.B. edited and revised manuscript; A.J.K. and C.M.B. interpreted results of experiments; C.M.B. conceived and designed research; C.M.B. drafted manuscript; C.M.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Robert Krauss for Boc and Cdo in situ probe templates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen BL, Song JY, Izzi L, Althaus IW, Kang JS, Charron F, Krauss RS, McMahon AP. Overlapping roles and collective requirement for the coreceptors GAS1, CDO, and BOC in SHH pathway function. Dev Cell 20: 775–787, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arman E, Haffner-Krausz R, Chen Y, Heath JK, Lonai P. Targeted disruption of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor 2 suggests a role for FGF signaling in pregastrulation mammalian development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 5082–5087, 1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avlan D, Gündoğdu G, Tașkınlar H, Delibaș A, Naycı A. Relationships among vesicoureteric reflux, urinary tract infection and renal injury in children with non-neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. J Pediatr Urol 7: 612–615, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao M, Liu B, Cunha G, Baskin L. Urothelium patterns bladder smooth muscle location. Pediatr Res 64: 352–357, 2008. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318180e4c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao M, Tasian G, Wang MH, Liu B, Cunha G, Baskin L. Urothelium-derived Sonic hedgehog promotes mesenchymal proliferation and induces bladder smooth muscle differentiation. Differentiation 79: 244–250, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caubit X, Lye CM, Martin E, Coré N, Long DA, Vola C, Jenkins D, Garratt AN, Skaer H, Woolf AS, Fasano L. Teashirt 3 is necessary for ureteral smooth muscle differentiation downstream of SHH and BMP4. Development 135: 3301–3310, 2008. doi: 10.1242/dev.022442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng W, Yeung CK, Ng YK, Zhang JR, Hui CC, Kim PC. Sonic Hedgehog mediator Gli2 regulates bladder mesenchymal patterning. J Urol 180: 1543–1550, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeSouza KR, Saha M, Carpenter AR, Scott M, McHugh KM. Analysis of the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway in normal and abnormal bladder development. PLoS One 8: e53675, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deveaud CM, Macarak EJ, Kucich U, Ewalt DH, Abrams WR, Howard PS. Molecular analysis of collagens in bladder fibrosis. J Urol 160: 1518–1527, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eastman R Jr, Leaf EM, Zhang D, True LD, Sweet RM, Seidel K, Siebert JR, Grady R, Mitchell ME, Bassuk JA. Fibroblast growth factor-10 signals development of von Brunn’s nests in the exstrophic bladder. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1094–F1110, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00056.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grieshammer U, Cebrián C, Ilagan R, Meyers E, Herzlinger D, Martin GR. FGF8 is required for cell survival at distinct stages of nephrogenesis and for regulation of gene expression in nascent nephrons. Development 132: 3847–3857, 2005. doi: 10.1242/dev.01944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hains D, Sims-Lucas S, Kish K, Saha M, McHugh K, Bates CM. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 in kidney mesenchyme. Pediatr Res 64: 592–598, 2008. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318187cc12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hains DS, Sims-Lucas S, Carpenter A, Saha M, Murawski I, Kish K, Gupta I, McHugh K, Bates CM. High incidence of vesicoureteral reflux in mice with Fgfr2 deletion in kidney mesenchyma. J Urol 183: 2077–2084, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haraguchi R, Matsumaru D, Nakagata N, Miyagawa S, Suzuki K, Kitazawa S, Yamada G. The hedgehog signal induced modulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling: an essential signaling relay for urinary tract morphogenesis. PLoS One 7: e42245, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haraguchi R, Motoyama J, Sasaki H, Satoh Y, Miyagawa S, Nakagata N, Moon A, Yamada G. Molecular analysis of coordinated bladder and urogenital organ formation by Hedgehog signaling. Development 134: 525–533, 2007. doi: 10.1242/dev.02736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikeda Y, Kanai A. Urotheliogenic modulation of intrinsic activity in spinal cord-transected rat bladders: role of mucosal muscarinic receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F454–F461, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90315.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Islam SS, Mokhtari RB, Kumar S, Maalouf J, Arab S, Yeger H, Farhat WA. Spatio-temporal distribution of Smads and role of Smads/TGF-β/BMP-4 in the regulation of mouse bladder organogenesis. PLoS One 8: e61340, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Evolution of the Fgf and Fgfr gene families. Trends Genet 20: 563–569, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landau EH, Jayanthi VR, Churchill BM, Shapiro E, Gilmour RF, Khoury AE, Macarak EJ, McLorie GA, Steckler RE, Kogan BA. Loss of elasticity in dysfunctional bladders: urodynamic and histochemical correlation. J Urol 152: 702–705, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B, Feng D, Lin G, Cao M, Kan YW, Cunha GR, Baskin LS. Signalling molecules involved in mouse bladder smooth muscle cellular differentiation. Int J Dev Biol 54: 175–180, 2010. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082610bl. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romer AI, Singh J, Rattan S, Krauss RS. Smooth muscle fascicular reorientation is required for esophageal morphogenesis and dependent on Cdo. J Cell Biol 201: 309–323, 2013. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiroyanagi Y, Liu B, Cao M, Agras K, Li J, Hsieh MH, Willingham EJ, Baskin LS. Urothelial sonic hedgehog signaling plays an important role in bladder smooth muscle formation. Differentiation 75: 968–977, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sims-Lucas S, Argyropoulos C, Kish K, McHugh K, Bertram JF, Quigley R, Bates CM. Three-dimensional imaging reveals ureteric and mesenchymal defects in Fgfr2-mutant kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2525–2533, 2009. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009050532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sims-Lucas S, Cullen-McEwen L, Eswarakumar VP, Hains D, Kish K, Becknell B, Zhang J, Bertram JF, Wang F, Bates CM. Deletion of Frs2α from the ureteric epithelium causes renal hypoplasia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1208–F1219, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00262.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sims-Lucas S, Cusack B, Baust J, Eswarakumar VP, Masatoshi H, Takeuchi A, Bates CM. Fgfr1 and the IIIc isoform of Fgfr2 play critical roles in the metanephric mesenchyme mediating early inductive events in kidney development. Dev Dyn 240: 240–249, 2011. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sims-Lucas S, Cusack B, Eswarakumar VP, Zhang J, Wang F, Bates CM. Independent roles of Fgfr2 and Frs2α in ureteric epithelium. Development 138: 1275–1280, 2011. doi: 10.1242/dev.062158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sims-Lucas S, Di Giovanni V, Schaefer C, Cusack B, Eswarakumar VP, Bates CM. Ureteric morphogenesis requires Fgfr1 and Fgfr2/Frs2α signaling in the metanephric mesenchyme. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 607–617, 2012. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011020165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tripathi P, Wang Y, Casey AM, Chen F. Absence of canonical Smad signaling in ureteral and bladder mesenchyme causes ureteropelvic junction obstruction. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 618–628, 2012. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 40: e115, 2012. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ural Z, Ulman I, Avanoglu A. Bladder dynamics and vesicoureteral reflux: factors associated with idiopathic lower urinary tract dysfunction in children. J Urol 179: 1564–1567, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Batavia JP, Ahn JJ, Fast AM, Combs AJ, Glassberg KI. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and vesicoureteral reflux in children with lower urinary tract dysfunction. J Urol 190 Suppl: 1495–1499, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker KA, Sims-Lucas S, Caruana G, Cullen-McEwen L, Li J, Sarraj MA, Bertram JF, Stenvers KL. Betaglycan is required for the establishment of nephron endowment in the mouse. PLoS One 6: e18723, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker KA, Sims-Lucas S, Di Giovanni VE, Schaefer C, Sunseri WM, Novitskaya T, de Caestecker MP, Chen F, Bates CM. Deletion of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 from the peri-wolffian duct stroma leads to ureteric induction abnormalities and vesicoureteral reflux. PLoS One 8: e56062, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 34.Wang Y, Tripathi P, Guo Q, Coussens M, Ma L, Chen F. Cre/lox recombination in the lower urinary tract. Genesis 47: 409–413, 2009. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu K, Xu J, Liu Z, Sosic D, Shao J, Olson EN, Towler DA, Ornitz DM. Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development 130: 3063–3074, 2003. doi: 10.1242/dev.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao H, Kegg H, Grady S, Truong HT, Robinson ML, Baum M, Bates CM. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in the ureteric bud. Dev Biol 276: 403–415, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]