Abstract

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation that contributes to disease pathophysiology. Exercise has anti-inflammatory effects, but the impact of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) is not known. The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of a single session of HIIT on cellular, molecular, and circulating markers of inflammation in individuals with T2D. Participants with T2D (n = 10) and healthy age-matched controls (HC; n = 9) completed an acute bout of HIIT (7 × 1 min at ~85% maximal aerobic power output, separated by 1 min of recovery) on a cycle ergometer with blood samples obtained before (Pre), immediately after (Post), and at 1 h of recovery (1-h Post). Inflammatory markers on leukocytes were measured by flow cytometry, and TNF-α was assessed in both LPS-stimulated whole blood cultures and plasma. A single session of HIIT had an overall anti-inflammatory effect, as evidenced by 1) significantly lower levels of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 surface protein expression on both classical and CD16+ monocytes assessed at Post and 1-h Post compared with Pre (P < 0.05 for all); 2) significantly lower LPS-stimulated TNF-α release in whole blood cultures at 1-h Post (P < 0.05 vs. Pre); and 3) significantly lower levels of plasma TNF-α at 1-h Post (P < 0.05 vs. Pre). There were no differences between T2D and HC, except for a larger decrease in plasma TNF-α in HC vs. T2D (group × time interaction, P < 0.05). One session of low-volume HIIT has immunomodulatory effects and provides potential anti-inflammatory benefits to people with, and without, T2D.

Keywords: inflammation, tumor necrosis factor-α, innate immunity, leukocyte, CD14+ monocyte

chronic low-grade inflammation, characterized by increases in basal leukocyte numbers, circulating proinflammatory cytokines, and/or acute-phase reactants, is implicated in the pathogenesis of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) (45). While the underlying cause of inflammation has not yet been fully elucidated, studies have shown elevation in surface protein expression of Toll-like receptors [TLRs; (10)] and augmented release of proinflammatory cytokines by immune cells isolated from patients with T2D compared to age-matched normoglycemic controls (11), correlating altered immune cell phenotype and function with the inflammatory pathology in T2D. TLRs are conserved pattern-recognition receptors that recognize a variety of exogenous and endogenous pathogens to coordinate innate immune responses (26). Increased TLR2 and TLR4 expression and the resulting proinflammatory environment are associated with a cluster of cardiometabolic risk factors, including insulin resistance, T2D, and atherosclerosis (10).

In addition to elevated TLRs, there is also evidence that monocyte subsets may be skewed toward a more proinflammatory profile in T2D (14). Monocytes can be categorized as classic, intermediate, and nonclassical with the use of immunofluorescence analysis to determine cell surface expression of CD14 and CD16 (60). CD14++/CD16− “classical” monocytes are regarded as anti-inflammatory, whereas CD16+, i.e., intermediate and nonclassical, monocytes are considered as proinflammatory (4). CD16+ monocytes produce higher levels of TNF-α, compared with classical monocytes when stimulated with the same concentration of bacterial LPS and other microbial ligands (4). CD16+ monocytes also show a blunted production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin IL-10 (5). Additionally, CD16+ monocytes are reported to have elevated surface expression of TLR2 and TLR4 compared with classical monocytes (20), further supporting the notion that CD16+ monocytes have a “proinflammatory” phenotype.

Exercise improves metabolic health and is a frontline therapy for the treatment and prevention of T2D (1a). One potent systemic benefit of exercise is thought to be its anti-inflammatory effects (37). Some of the anti-inflammatory effects of chronic exercise are likely attributable to a reduction in adipose tissue (3), but there is also growing evidence that acute exercise, in the absence of weight loss, can directly impact immune cell phenotype and alter systemic inflammatory mediators (for review, see Ref. 37). In addition to benefits on glucose control and cardiorespiratory fitness (48), intervention studies report that exercise training can reduce the level of circulating proinflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and TNF-α (25, 29). An increase in circulating IL-6 following acute exercise is well established (43) and is followed by the appearance of anti-inflammatory factors IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-10, and soluble TNF receptor (42). For this reason, exercise-induced elevations in circulating IL-6 are generally considered to be anti-inflammatory in nature (43). The ability of exercise to reduce monocyte TLRs is another hypothesized mechanism through which acute exercise may create a systemic anti-inflammatory milieu (16). Most studies have shown reduced monocyte TLR2 and TLR4 expression after acute endurance exercise (19), but there are reports of increased monocyte TLRs immediately and 1 h following prolonged strenuous exercise (60-km cycling ergometer time trial) (5). The influence of exercise on TLR expression on other distinct immune cells, including granulocytes/neutrophils, has not been adequately studied, but our initial studies show that short-term exercise training can reduce TLR expression on neutrophils in addition to monocytes in individuals with obesity (47), suggesting a systemic impact of exercise for lowering leukocyte TLRs. Research also shows that exercise training can lead to a reduction in the ratio of CD16+ proinflammatory monocytes to classical monocytes (58), suggesting that exercise might promote skewing toward a more anti-inflammatory monocyte profile, but this has not been tested in T2D.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) has gained recent attention as a time-efficient exercise strategy for improving cardiometabolic health, providing a unique physiological stimulus compared with traditional exercise (18). Several studies have shown potent glucose lowering and cardiovascular health benefits from HIIT (27, 35, 36), and a recent meta-analysis concluded that HIIT was superior to traditional continuous exercise for improving insulin sensitivity and glucose control (24). These findings highlight the potential utility of HIIT as a therapeutic exercise strategy in T2D, but the impact of HIIT on inflammation in T2D has not, to our knowledge, been studied. There are speculations that vigorous exercise may be proinflammatory in people with cardiometabolic disease (28), even though empirical evidence showing that HIIT promotes inflammation is lacking. Further understanding of the inflammatory impact of HIIT in T2D is needed before this exercise strategy can be promoted for providing anti-inflammatory benefits.

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the impact of a single bout of HIIT on indicators of cellular and systemic inflammation in people with T2D. We examined 1) leukocyte numbers and expression of TLR2 and TLR4 on classical monocytes, CD16+ monocytes, and CD16+ granulocytes (i.e., neutrophils); 2) ex vivo endotoxin-stimulated cytokine secretion in whole blood cultures as an index of innate immune cell activation; and 3) circulating TNF-α, to test the hypothesis that acute HIIT would promote anti-inflammatory effects in T2D. An age-matched normoglycemic healthy control group (HC) was included to help ascertain whether the presence of T2D influenced the immunomodulatory effects of acute HIIT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Ten T2D patients and nine age-matched normoglycemic controls were recruited for this two-group time-series study. T2D participants were diagnosed by a physician, according to Canadian Diabetes Association criteria, based on hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5, fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l, and/or 2-h oral glucose tolerance test glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l. All T2D participants were enrolled in the Kelowna Diabetes Program (23) and had an A1c value <8.0% [mean (SD) = 6.5 (0.7)]. T2D patients were screened for any cardiovascular abnormalities and cleared for vigorous exercise by a cardiologist via a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) stress test before baseline fitness testing. Descriptive characteristics are presented in Table 1. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study, which was approved by the UBC Clinical Research Ethics Board (H14-01636). Participants underwent baseline fitness testing using a ramp protocol (15 W/min) on an electronically braked cycle ergometer (Lode Excalibur, Groningen, The Netherlands) to determine peak power output (defined as the highest Watts achieved) and peak oxygen uptake (V̇o2peak). Expired gas was collected via a mouthpiece (7600 Series V2 Mask, Hans Rudolph, Shawnee, KS), and oxygen uptake (V̇o2) and carbon dioxide output (V̇co2) were determined by a metabolic cart (Parvomedics TrueOne 2400, Salt Lake City, UT), which was calibrated with a 3.0-liter syringe and gases of known concentration before each test. Participants were instructed to pedal at a constant rate above 50 rpm for the duration of the test, which was stopped when participants could not maintain this cadence and/or volitional exhaustion. V̇o2peak was defined as the highest 30-s average V̇o2. Heart rate was monitored continuously (Polar Heart Rate Sensor H1, Polar, Kempele, Finland), and maximal heart rate (HR) was defined as the highest value attained during the test. Criteria for verifying maximal exertion were as follows: a peak HR of at least 90% of age-predicted maximal HR (based on 220 bpm – age) and a peak respiratory exchange ratio (RER) of at least 1.15 (38). All participants met these criteria.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Type 2 Diabetes | Healthy Controls | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg | 99.6 ± 17.0 | 71.2 ± 13.6 | <0.001 |

| Height, cm | 169.4 ± 11.8 | 168.8 ± 7.4 | 0.89 |

| BMI | 34.8 ± 5.9 | 24.8 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

| Age, yr | 57.9 ± 5.4 | 55.8 ± 9.0 | 0.53 |

| V̇o2peak, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 18.9 ± 4.0 | 31.4 ± 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Wattpeak, W | 147.6 ± 34.0 | 189.4 ± 43.1 | 0.03 |

| Metformin only (n) | 7 | 0 | NA |

| Sulfonylurea + GLP1 agonist | 1 | 0 | NA |

| SGLT2 inhibitor + GLP1 agonist | 1 | 0 | NA |

| DPP4 inhibitor | 1 | 0 | NA |

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Type 2 diabetes: n = 5 males, n = 5 females. Healthy controls: n = 4 males, n = 5 females. BMI, body mass index; GLP1, glucagon-like peptide; SGLT2, sodium-dependent glucose transporter-2; NA, not applicable.

Participants with T2D participated in a 12-wk exercise trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02251301) and completed four cycling HIIT familiarization sessions involving 4–6 × 1-min intervals before the acute exercise trial, which was done across 2 wk to introduce them to HIIT, ensure that there were no abnormal blood pressure or HR responses to HIIT, and build up to the exercise protocols for testing days. Age-matched normoglycemic controls self-reported completing 150–300 min of light-to-moderate physical activity per week (e.g., walking, golfing) but were not participating in any structured exercise training before the acute exercise trial. Sample size was calculated to detect an expected 30–50% reduction in TLR2 (19) and/or TLR4 (19, 41) described previously on CD14+ monocytes, using means and standard deviations for median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD14+ TLR2 and TLR4 obtained from previous work in our laboratory (n = 25 T2D patients). Using the sample size calculator G Power (version 3.1), we determined that 10 participants were needed at 80% power with α set at 0.05, assuming a moderate correlation (r = 0.5) among repeated measures.

Acute Exercise Trial

All participants refrained from exercise for 48 h before the acute exercise trial. T2D participants maintained their normal medication schedule throughout the study, including the day of the acute exercise trial. Subjects warmed up on the cycle ergometer at 30 W for 4 min before completing a HIIT session that was based on previously published protocols (35, 47) and consisted of 7 × 1-min intervals at 85% peak power output with 1-min rest periods at 15% peak power output between HIIT bouts. A 3-min cool down was completed after the final interval. HR data were collected continuously by 12-lead ECG, and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE; CR-10) (6) were assessed during the final 10 s of each interval. Exercise began at either 11:00 AM or 4:00 PM, 4 h postprandial, and water was provided ad libitum throughout.

Blood Samples

Before the acute exercise trial, an in-dwelling 21-gauge venous catheter (BD Nexiva, Sandy, UT) was inserted into an antecubital vein and kept patent with sterile saline. Venous blood samples were taken before (Pre), immediately after (Post), and 1 h after (1-h Post) the exercise session. These time points were chosen to be consistent with previous studies showing exercise-induced reductions in TLRs (5, 19, 41, 52). Blood was collected into Vacutainers containing EDTA and kept at room temperature (for whole blood culture experiments) or on ice (for all other parameters) before further analysis. A portion of the blood collected was centrifuged at 1,550 g for 15 min at 4°C with plasma frozen at −80°C for later analysis of TNF-α via MagPIX assay (high-sensitivity T-cell HSTCMAG-28SK; Millipore, Billerica, MA), as we have previously described (47). The remainder of the blood was used for whole blood cultures and flow cytometry.

Whole Blood Cultures

Whole blood cultures were prepared by diluting blood 10 times in serum-free RPMI media (Sigma) supplemented with penicillin (50 U/ml) and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) containing 5 mM glucose and seeding cells in 12 × 75 mm polystyrene culture tubes at 540 μl per well, as we have described previously (47). At each time point, one culture tube was left unstimulated, and one was stimulated with 10 ng/ml bacterial LPS (from Escherichia coli 055:B5; L6529; Sigma). Supernatants were collected after 4 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for analyses of TNF-α production via MagPIX assay (Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel HCYTOMAG-60K), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow Cytometry

FcR blocking reagent (cat. no. 130-059-901; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) was added to 90 μl of whole blood and allowed to incubate for 10 min at 4°C in the dark. This was followed by the addition of conjugated antibodies specific for human CD14 (Vioblue, cat. no. 130-094-364; Miltenyi Biotec), CD16 (FITC, cat. no. 130-091-244, Miltenyi Biotec), TLR2 (PE, cat. no. 130-099-016; Miltenyi Biotec), and TLR4 (APC, cat. no. 130-096-236; Miltenyi Biotec). Samples were then incubated for 10 min at 4°C in the dark. Finally, 1 ml of red blood cell lysis buffer (cat. no. 120-001-339; Miltenyi Biotec) was added to the samples, and a final incubation step of 15 min at room temperature in the dark was administered. Immediately before flow cytometer analysis, 2 μl of propidium idodide (PI) (cat. no. 130-093-233; Miltenyi Biotec) were added to each sample for dead cell exclusion. Samples were analyzed on a MACSQuant Analyzer 10 flow cytometer. Ten thousand monocytes, identified by scatter profile, were counted in each sample. Bank instrument settings were used to account for any drift in laser strength over time. Compensation was performed before analysis to control for any spillover among fluorochromes. Flow cytometry data were analyzed with MACSQuantify version 2.6 (Miltenyi Biotec).

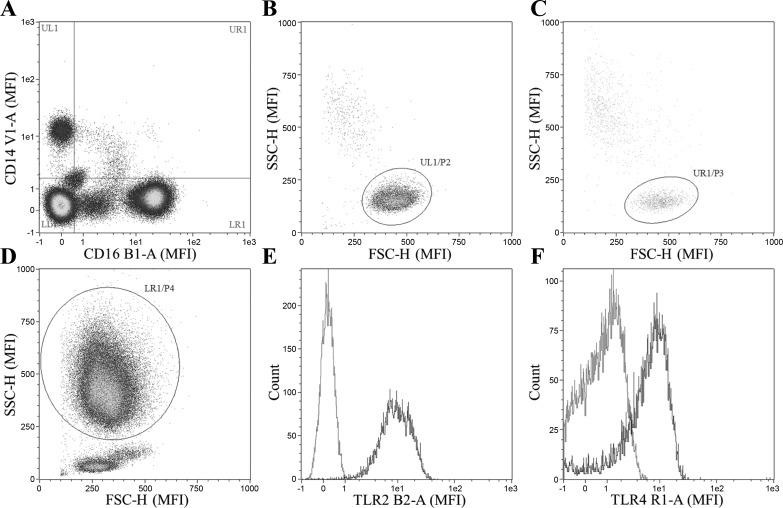

CD14+/CD16− (i.e., classical monocytes), CD14+/CD16+ monocytes (i.e., CD16+ monocytes), and CD16+ neutrophils were identified via a hierarchical gating strategy. Specifically, cells that stained positive for PI were first excluded from analysis, and then cells were characterized as CD14+/CD16−, CD14+/CD16+, or CD14−/CD16+ populations (Fig. 1A). The CD14+/CD16− and CD14+/CD16+ populations were then confirmed to be monocytes (Fig. 1, B and C), and the CD14−/CD16+ population was confirmed to be neutrophils (Fig. 1D) via characteristic scatter profile. TLR2 and TLR4 median fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1, E and F, respectively) were then determined on each of the cell types (classical monocytes, CD16+ monocytes, and neutrophils) with fluorescence minus one controls used to determine gating on positive and negative populations. Monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes were identified by their characteristic scatter profiles, and total leukocyte number was calculated by the addition of the three subpopulations. If cell populations had less than 300 total events, TLR expression was not analyzed due to insufficient events.

Fig. 1.

Gating strategy for analysis of surface Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 on monocytes and neutrophils. Cells that stained positive for propidium idodide were first excluded from analysis. Cells are first gated on expression of CD14+/CD16− (classical monocytes), CD14−/CD16+ (CD16+ neutrophils), or both CD14+/CD16+ (CD16+ monocytes) (A). Cell type is then confirmed via characteristic forward and side-scatter profile for classical monocytes, CD16+ monocytes, and neutrophils (B, C, and D, respectively). Cell surface TLR2 and TLR4 expression were then measured on each cell type (i.e., classical monocytes, CD16+ monocytes, and CD16+ neutrophils), Fluorescence minus one controls are displayed in gray (E and F). MFI, median fluorescence intensity; SSC-H, side scatter height; FSC-H, forward scatter height.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R (46). Statistical outliers were objectively removed from analysis using interquartile range with a multiplier of 2.2 based on the method by Hoaglin and Iglewics (22). Briefly, the 25th and 75th percentiles were determined and added to the interquartile range multiplied by 2.2 to calculate the lower and upper limits. On the basis of these limits, values that fell outside were deemed to be outliers and removed from the analyses. Normality was assessed using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Non-normal data were log or square-root transformed to reduce skewness. A mixed two-factor ANOVA was used with time as a within-subject factor and T2D status as a between-subject factor to analyze differences in variables in response to exercise. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Significant main effects of time were probed with Fisher LSD post hoc tests with groups collapsed, whereas interactions were probed with Fisher LSD post hoc tests across time within groups.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

T2D participants (n = 5 males, n = 5 females) had a higher body mass, lower V̇o2peak, and lower Wattpeak compared with age-matched HC (n = 4 males, n = 5 females) (Table 1). All participants completed the HIIT session with no issues. There were no differences in mean percent maximal HR (T2D: 81.4 ± 8.9%; HC: 83.8 ± 6.4%, P = 0.52) or mean RPE (T2D: 5 ± 2; HC: 5 ± 2, P = 0.46) measured during exercise between T2D and controls. Baseline carbohydrate, protein, fat, or energy intake assessed by 24-h dietary recall did not differ between T2D and HC (data not shown).

Leukocyte Numbers

The impact of a single session of HIIT on blood leukocyte numbers is presented in Table 2. There was a main effect of time for total leukocyte concentration (P < 0.001; n = 9 HC, n = 10 T2D). The total number of leukocytes in the blood increased immediately after exercise (P < 0.001, Post vs. Pre) and then declined at 1 h following exercise (P < 0.001, 1-h Post vs. Post). There was also a main effect of group (P = 0.03) with T2D participants having a higher total leukocyte count than HC. There was a main effect of time (P < 0.001; n = 9 HC, n = 10 T2D) for classical monocyte numbers. Classical monocyte numbers were elevated immediately following exercise (Post) compared with before exercise (Pre) (P < 0.001) and decreased 1-h postexercise (1-h Post) compared with preexercise (P = 0.04, 1-h Post vs. Pre) and postexercise (P < 0.001, 1-h Post vs. Post). There was also a main effect of time for CD16+ monocytes (P = 0.004; n = 8 HC, n = 10 T2D). CD16+ monocyte numbers were elevated immediately postexercise compared with both preexercise (P = 0.01, Post vs. Pre) and 1-h postexercise (P = 0.005, 1-h Post vs. Post). A main effect of time was detected for neutrophil numbers (P < 0.001; n = 9 HC, n = 10 T2D) with post hoc tests, indicating an increase immediately postexercise compared with both preexercise (P < 0.001) and 1-h postexercise (P < 0.001). There was also a main effect of group (P = 0.02) with T2D displaying higher numbers of neutrophils than the HC. There were no group × time interactions for any of the leukocyte subsets analyzed (all P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Leukocyte response to an acute bout of high-intensity interval training

| Cell Type | Type 2 Diabetes |

Healthy Controls |

P Value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | 1-h Post | Pre | Post | 1-h Post | Group | Time | Group × Time | |

| Classical monocytes × 105/ml | 3.2 ± 0.40 | 4.5 ± 0.58* | 3.1 ± 0.29*# | 3.3 ± 0.83 | 4.2 ± 1.6* | 3.1 ± 0.92# | 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.24 |

| CD16+ monocytes × 105/ml | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 0.27 ± 0.19* | 0.18 ± 0.11# | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 0.17 ± 0.11* | 0.09 ± 0.04# | 0.3 | 0.004 | 0.17 |

| Neutrophils × 105/ml | 30.6 ± 6.2 | 44.1 ± 11.8* | 32.2 ± 5.8# | 25.3 ± 7.6 | 32.1 ± 11.2* | 24.4 ± 5.4# | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.21 |

| Lymphocytes × 105/ml | 15.9 ± 4.2 | 28.0 ± 7.3* | 16.8 ± 4.7# | 15.6 ± 3.9 | 26.1 ± 10.4* | 15.1 ± 3.4# | 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.64 |

| CD16+ monocytes (% of total monocytes) | 4.5 ± 3.5 | 5.4 ± 3.7 | 5.3 ± 3.0 | 4.8 ± 2.4 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.08 |

| Total leukocytes × 105/ml | 50.3 ± 7.9 | 75.1 ± 18.3* | 52.6 ± 8.3# | 42.8 ± 13.1 | 58.9 ± 18.6* | 43.5 ± 7.8# | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.77 |

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Type 2 diabetes: n = 5 males, n = 5 females. Healthy controls: n = 4 males, n = 5 females.

Fisher least significant difference post hoc vs. Pre (time main effect, P < 0.05).

Fisher post hoc vs. Post (time main effect, P < 0.05).

Toll-Like Receptor 2

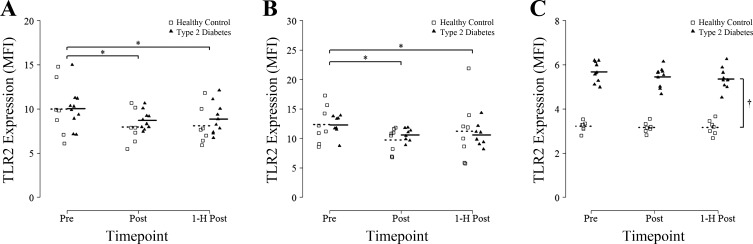

A significant main effect of time was found for TLR2 expression on classical monocytes (P = 0.01; n = 7 HC, n = 10 T2D). TLR2 expression on classical monocytes was decreased by ~16% Post (P = 0.007, Post vs. Pre) and by ~15% at 1-h Post (P = 0.03, 1-h Post vs. Pre) (Fig. 2A). There was no effect of group for TLR2 expression on classical monocytes (P = 0.38) and no interaction effect (P = 0.72). TLR2 expression on CD16+ monocytes showed a similar main effect of time (P = 0.007; n = 8 HC, n = 8 T2D) with post hoc tests revealing a significant decrease of 18% Post (P < 0.001, Post vs. Pre) and by ~11% 1-h Post (P = 0.04, 1-h Post vs. Pre) (Fig. 2B). There was no effect of group (P = 0.7) or interaction (P = 0.65) for TLR2 expression on CD16+ monocytes. An acute session of HIIT had no effect on CD16+ neutrophil TLR2 expression (P = 0.11; n = 8 HC, n = 10 T2D); however, there was a main effect of group with T2D expressing ~35% higher TLR2 than HC participants at all timepoints (P < 0.001; Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Toll-like receptor 2 expression on CD14+/CD16− classic monocytes, CD16+ monocytes, and CD16+ neutrophils in response to an acute bout of high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Blood samples were obtained before (Pre), immediately after (Post), and 1 h after (1-h Post) a single session of HIIT involving 7 × 1-min at 85% peak power output and TLR2 MFI was measured by flow cytometry on CD14+/CD16− monocytes (A), CD16+ monocytes (B), and CD16+ neutrophils (C). Group means are denoted by dotted (Healthy Controls) or solid (Type 2 Diabetes) horizontal lines. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time for classical monocytes and CD16+ monocytes (all P < 0.05). *P < 0.05 vs. Pre [Fisher least significant difference (LSD) post hoc]. †A main effect of group was also detected for CD16+ neutrophils (P < 0.05).

Toll-like Receptor 4

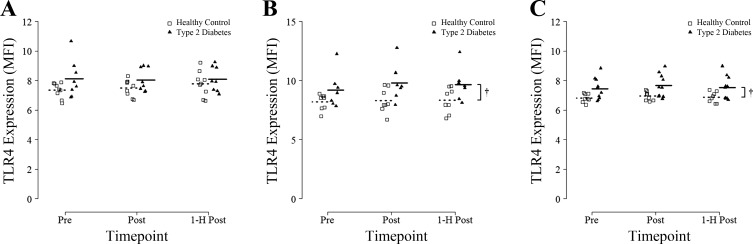

There were no effects of time (P = 0.56; n = 9 HC, n = 8 T2D), group (P = 0.11), or interaction (P = 0.60) for TLR4 expression on classical monocytes (Fig. 3A). There were no significant effects of time (P = 0.22; n = 8 HC, n = 7 T2D), nor was there an interaction (P = 0.4) for TLR4 expression on CD16+ monocytes; however, there was a main effect of group with T2D having ~15% higher TLR4 expression compared with HC participants across all timepoints (P = 0.049; Fig. 3B). There were no effects of time (P = 0.25; n = 8 HC, n = 10 T2D), nor was there an interaction (P = 0.93) for TLR4 expression on CD16+ neutrophils. There was a main effect of group with T2D participants displaying ~10% higher TLR4 expression compared with HC on CD16+ neutrophils (P = 0.02; Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

TLR4 expression on CD14+/CD16− classic monocytes, CD16+ monocytes, and CD16+ neutrophils in response to an acute bout of HIIT. Blood samples were obtained before (Pre), immediately after (Post), and 1 h after (1-H Post) a single session of HIIT involving 7 × 1 min at 85% peak power output and TLR4 MFI was measured by flow cytometry on CD14+/CD16− monocytes (A), CD16+ monocytes (B), and CD16+ neutrophils (C). Group means are denoted by dotted (Healthy Controls) or solid (Type 2 Diabetes) horizontal lines. †Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of group for CD16+ monocytes and CD16+ neutrophils (both P < 0.05).

Whole Blood Cultures

Absolute cytokine concentration.

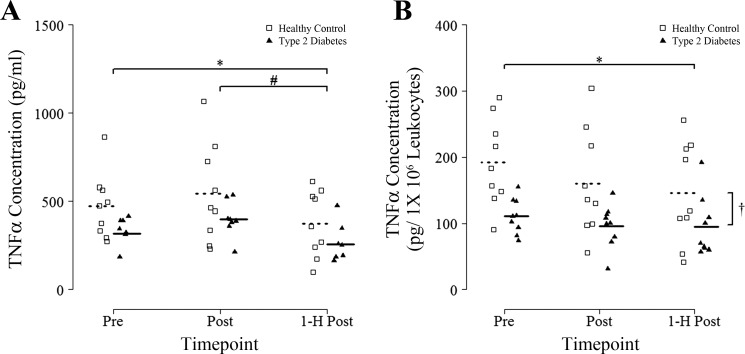

There were no effects of group for LPS-stimulated TNF-α release (P = 0.12; n = 9 HC, n = 8 T2D) nor was there an interaction (P = 0.76). There was a main effect of time for LPS-stimulated TNF-α release (P < 0.001) with post hoc tests revealing a ~20% decrease 1-h Post (P = 0.02) compared with Pre. TNF-α release was also significantly lower (by ~33%) 1-h postexercise compared with immediately postexercise (P = 0.001; Fig. 4A). Unstimulated TNF-α release was largely undetectable and unchanged at all time points (data not shown; n = 3 HC, n = 4 T2D).

Fig. 4.

Whole blood culture TNF-α concentration from 4-h supernatants stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS in response to an acute bout of HIIT. Blood samples were obtained before (Pre), immediately after (Post), and 1 h after (1-H Post) a single session of HIIT involving 7 × 1-min at 85% peak power output and absolute TNF-α (A) and leukocyte concentration corrected TNF-α (B) secretion in whole blood cultured in the presence of 10 ng/ml LPS was measured. Supernatants were collected after 4 h in culture, and TNF-α was measured by Magpix ELISA. Group means are denoted by dotted (Healthy Controls) or solid (Type 2 Diabetes) horizontal lines. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time for absolute TNF-α concentration (P < 0.05) and a significant main effect of group for leukocyte-corrected TNF-α concentration (†P < 0.05). *P < 0.05 vs. Pre (Fisher LSD post hoc). #P < 0.05 vs. Post (Fisher LSD post hoc).

Leukocyte corrected cytokine release.

When corrected for total leukocyte numbers, there was a main effect of time (P = 0.03; n = 9 HC, n = 9 T2D) for LPS-stimulated TNF-α release, with a ~20% decrease seen at 1-h Post compared with Pre (P = 0.03 vs. Pre), as well as a main effect of group with T2D releasing ~39% less TNF-α than HC (P = 0.02), but no interaction (P = 0.78; Fig. 4B). Unstimulated leukocyte-corrected TNF-α release was largely undetectable and unchanged at all time points (data not shown; n = 3 HC, n = 4 T2D).

Plasma cytokines.

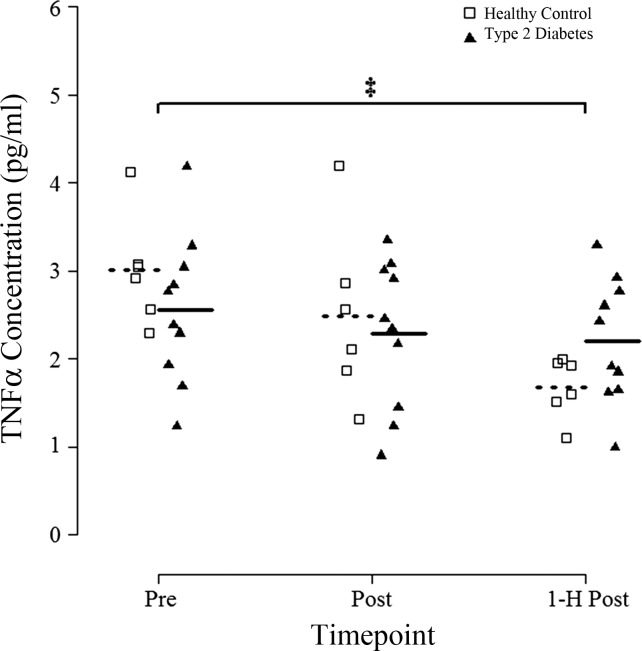

There was a group × time interaction for plasma TNF-α (P = 0.02; n = 6 HC, n = 10 T2D). Visual inspection of Fig. 5 suggests a larger decrease after exercise in HC. Post hoc analysis revealed an ~14% decrease in T2D (P = 0.04 vs. Pre) and a 44% decrease in HC (P = 0.005) 1-h Post compared with Pre.

Fig. 5.

Circulating plasma TNF-α concentration in response to an acute bout of HIIT. Blood samples were obtained before (Pre), immediately after (Post), and 1 h after (1-H Post) a single session of HIIT involving 7 × 1-min at 85% peak power output and TNF-α in plasma samples was measured by Magpix ELISA. Groups means are denoted by dotted (Healthy Controls) or solid (Type 2 Diabetes) horizontal lines. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant group × time interaction for TNF-α concentration (P < 0.05). ‡P < 0.05 vs. Pre within each group (Fisher LSD post hoc).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that, in both T2D and HC, one bout of HIIT significantly reduces TLR2 expression on classical and CD16+ monocytes measured immediately after and at 1-h recovery from exercise. This was accompanied by small but significant reductions in both TNF-α production from LPS-stimulated whole blood cultures and in circulating plasma TNF-α. Overall, this suggests an anti-inflammatory effect of acute HIIT.

Effects of Exercise on TLRs

TLRs propagate an innate immune response to multiple ligands (including endotoxin, free fatty acids, and glucose) that may be elevated in T2D, and it is theorized that higher TLR expression may drive chronic low-grade inflammation in T2D (10–12). One of the proposed cellular mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory effect of exercise is a reduction in TLR expression (37). A reduction in cell surface TLR2 and TLR4 has been demonstrated after both acute bouts of exercise and longer-duration training studies (41, 52, 55). The majority of the studies investigating the effect of acute exercise, however, tend to utilize relatively long-duration exercise protocols lasting ≥90 min (5, 19, 33, 41, 52). In addition to reductions in cell-surface expression of TLRs, recent evidence also points to an upregulation of genes involved in the negative regulation of TLR signaling in whole blood cultures following a single bout of exercise (1). Exercise-induced reductions in TLR expression and signaling may be of particular relevance to inflammation in T2D because mechanistic studies have found that hyperglycemia can increase TLR2 and TLR4 expression in monocytes (10, 11), and both TLR2 (7) and TLR4 (51) are implicated in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. We found that, on both classical and CD16+ monocytes, one bout of HIIT reduced TLR2 expression, which is in agreement with previous work using longer-duration exercise bouts (19, 33, 41). There were no differences in the response between groups, suggesting that HIIT had an equal impact on monocyte TLR2 reduction in T2D participants and HC. In contrast to previous work demonstrating a fairly consistent reduction in TLR4 after prolonged (>1 h) moderate-to-vigorous exercise (5, 19, 33, 41), we did not see any changes in TLR4. This may suggest that HIIT is not sufficient stimulus to reduce TLR4 and may have a preferential effect on TLR2. It is also possible that we did not detect an effect on TLR4 expression due to the timing of the blood measurements, although we feel that is unlikely, as past studies have observed changes at the timepoints chosen (5, 19, 41, 52). Given the previous research, it is reasonable to speculate that TLR4 may be more sensitive to exercise duration when compared with TLR2. As our primary purpose was to examine the impact of acute HIIT in T2D, we unfortunately did not include a comparison to prolonged continuous exercise, which we felt was largely impractical for patients with T2D. Indeed, T2D patients often cannot complete prolonged continuous exercise without rest breaks or sufficient acclimatization to the exercise (40, 57). The precise physiological mechanisms responsible for reductions in TLR expression in response to exercise have not been elucidated (for review, see Ref. 16). It is possible that the observed reduction in monocyte TLR2 expression after exercise is a consequence of receptor shedding, internalization, and/or suppression of gene expression. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation appears to be responsible for shedding of TLR2 from immune cells, which leads to an increase in soluble TLR2 (34). Acute exercise, which has been shown to increase circulating levels of MMP-9 (49), could promote TLR2 shedding, but definitively testing this hypothesis in humans remains difficult. Internalization of TLRs is thought to occur following ligand binding, where the TLR complex is recruited into lipid rafts and targeted to the Golgi apparatus (59). Many TLR agonists have been shown to increase during exercise, including free fatty acids and heat shock proteins (2, 13, 56), which could potentially be involved in this mechanism of TLR downregulation. It is also possible that the reduction in TLR2 expression on classical and CD16+ monocytes observed Post and 1-h Post was due to the addition of a different population of cells into circulation than those observed at Pre (e.g., monocytes that were previously in the marginated pool) that may have expressed lower levels of surface TLR2. However, as the goal of this study was to determine the impact of a single bout of HIIT on TLR2 and TLR4 expression, the mechanism behind this effect was not investigated.

The majority of studies in the literature have investigated the role of exercise on TLR expression in monocytes. A novel aspect of this study was the characterization of TLR2 and TLR4 expression on neutrophils (CD16+ granulocytes). Neutrophil TLR2 is implicated in cytokine expression and superoxide production (31), while neutrophil TLR4 plays a crucial role in cell survival (50). Although we observed a higher level of TLR2 and TLR4 on neutrophils in T2D compared with HC, there was no effect of exercise on neutrophil expression of either TLR2 or TLR4. These findings suggest that the impact of exercise on TLRs may be specific to monocytes.

Acute HIIT led to an expected increase in monocyte, neutrophils, and lymphocytes measured immediately after exercise (i.e., leukocytosis). Exercise-induced leukocytosis following a bout of high-intensity exercise is a well-established phenomenon, which has been demonstrated in both continuous and interval-type exercise (15, 17, 21). Neutrophils and monocytes are thought to be mobilized primarily from the marginal pool and possibly bone marrow (15, 21, 44), whereas lymphocytes are likely recruited from the spleen and other lymphoid organs, as well as the lungs and the walls of high-endothelial venules (32, 39). This effect is dependent on exercise-induced elevations in circulating epinephrine and cortisol (39). Leukocyte numbers returned to baseline levels 1 h after exercise, which is in contrast with steady-state exercise, where sustained leukocytosis has been shown to occur for up to 2 h into recovery (21). Even though T2D participants had higher total leukocytes, there were no apparent group differences in the impact of acute HIIT on leukocyte numbers, suggesting that T2D and HC respond similarly to this type of exercise. There were no effects of acute HIIT on the number or percentage of CD16+ monocytes, which suggests that acute vigorous exercise performed as HIIT does not impact the proportion of the main circulating monocyte subsets.

Cytokine Response

Interestingly, there was a small, yet statistically significant, reduction in plasma TNF-α 1 h after exercise in both T2D and HC. While both groups displayed lower levels of plasma TNF-α 1 h into recovery, the reduction appeared more pronounced in the HC group (group × time interaction effect). This reduction in circulating TNF-α could be interpreted as an anti-inflammatory effect of acute HIIT, although the mechanisms are not clear. In an attempt to better understand the impact of acute HIIT on cytokine secretion from leukocytes, we performed parallel whole blood culture experiments in both unstimulated and LPS-stimulated conditions. Unstimulated whole blood culture TNF-α secretion was largely undetectable, and there were no differences between groups or across time. In examining both absolute and leukocyte-corrected LPS-stimulated cytokine secretion in the whole blood cultures, the results tended to match the changes in plasma TNF-α, such that LPS-stimulated TNF-α release was lower at 1-h recovery from acute HIIT. Taken together, the reduction in plasma TNF-α and LPS-stimulated whole blood culture TNF-α at 1-h recovery support an anti-inflammatory effect of an acute bout of HIIT in T2D and HC participants.

Limitations

Most previous studies examining the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of acute exercise, including monocyte TLRs and LPS-stimulated cytokine release, have used prolonged continuous moderate-to-vigorous exercise protocols (5, 19, 33, 41, 52). Because of the increasing popularity and utility of HIIT for improving cardiometabolic health in T2D and the unlikelihood that previously inactive older adults with T2D would perform ≥1 h of moderate-to-vigorous intensity exercise, we focused on time-efficient HIIT in this study and, unfortunately, cannot directly compare HIIT to previous work involving more traditional endurance-oriented exercise.

In this study, we did not observe universally higher TLR expression in T2D compared with HC, which is inconsistent with previous findings by Dasu et al. (10), but it is in line with work from other groups (30). It is possible that we did not detect any baseline differences in TLR expression due to the fact that the T2D participants in our study were not newly diagnosed and were taking glucose-lowering medications (Table 1). Indeed, it has been shown that the commonly prescribed T2D medication metformin can decrease TLR4 expression on human monocytes (61).

Similar to previous research (53, 54), we used LPS to stimulate whole blood cultures to examine blood leukocyte cytokine secretion in response to a standard inflammatory insult. Although TLR2 has been shown to be involved in monocyte responses to LPS (8, 50), TLR4 is regarded as the main LPS-sensing receptor. Given that we saw reductions in TLR2 on monocytes following exercise and higher TLR2 on neutrophils in T2D, research involving stimulation of cultures with more pure TLR2 ligands, such as PamCSK4 or peptidoglycan, may provide more insight into the functional responses of these cells following receptor downregulation.

Although we examined leukocyte numbers, phenotype, and function in response to acute HIIT, it is not possible to examine or track inflammatory markers in immune cells that have infiltrated tissues (e.g., adipose, skeletal muscle, and blood vessels) in vivo in human studies. Future work is needed to determine whether the changes in monocyte TLR2 and cytokine secretion are also paralleled in tissue macrophages.

It is also worth noting that plasma TNF-α concentrations were not corrected for plasma volume shifts. The logic for this is to report plasma TNF-α concentrations that better represent the changing environment to which the circulating leukocytes were exposed.

It is important to note that the T2D participants had completed a brief familiarization period before the acute exercise trial. This involved four sessions of cycling HIIT (4–6 × 1-min intervals at ~80% maximal HR, RPE of ~5/10). This was deemed necessary to ensure the T2D participants could complete 7 × 1-min interval sessions, were accustomed to this type of vigorous exercise, and did not experience any abnormal HR or blood pressures responses to HIIT. This familiarization amounted to a very low volume of exercise, but the results may not generalize to T2D participants completely naïve to HIIT. Both the T2D and HC participants refrained from any exercise for 48 h before the acute trials, but the HC participants did not complete the four cycling HIIT familiarization sessions, as they were already habitually active for 150–300 min/wk, and completing such a low volume of familiarization HIIT was deemed unnecessary. The HC group was leaner and more fit but was included to assess what the response to HIIT would be in healthy older adults without the potential complications of obesity or other comorbidities. Additionally, the exercise trials took place 4 h postprandially to standardize the timing of exercise after a meal.

Perspectives and Significance

This study indicates that, in older adults with and without T2D, one bout of low-volume HIIT can reduce TLR2 expression, but not TLR4 expression, on monocytes. Acute low-volume HIIT had no discernable effect on neutrophil TLR2 or TLR4 expression. A single session of HIIT also led to reductions in both circulating and ligand-induced TNF-α. Taken together, these results indicate that HIIT is an efficient exercise stimulus for inducing cellular and molecular anti-inflammatory effects. As there was no indication of a proinflammatory effect of HIIT on the parameters measured in this study in either T2D patients or age-matched healthy controls, HIIT may be a suitable option for ameliorating the chronically elevated levels of inflammation implicated in T2D pathophysiology. Whether the anti-inflammatory effects induced by individual bouts of HIIT can culminate over time to improve health and impede the pathogenesis of T2D and its complications remains to be determined.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant (RGPIN 435807-13) to J. P. Little. J. P. Little is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award (MSH-141980).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors' responsibilities were as follows: J.P.L., C.D., and M.F. designed the study; C.D., M.F., J.P.L. and H.N. conducted research; J.P.L. and C.D. performed the statistical tests and wrote the final manuscript, which was edited by M.F. and H.N.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the enthusiastic collaboration of study participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbasi A, Hauth M, Walter M, Hudemann J, Wank V, Niess AM, Northoff H. Exhaustive exercise modifies different gene expression profiles and pathways in LPS-stimulated and un-stimulated whole blood cultures. Brain Behav Immun 39: 130–141, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association; Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, Chasan-Taber L, Albright AL, Braun B. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care 33: e147–e167, 2010. doi: 10.2337/dc10-9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asea A, Rehli M, Kabingu E, Boch JA, Bare O, Auron PE, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Novel signal transduction pathway utilized by extracellular HSP70: role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4. J Biol Chem 277: 15,028–15,034, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, Fernando F, Cavallo S, Cardelli P, Fallucca S, Alessi E, Letizia C, Jimenez A, Fallucca F, Pugliese G. Anti-inflammatory effect of exercise training in subjects with type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome is dependent on exercise modalities and independent of weight loss. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 20: 608–617, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belge KU, Dayyani F, Horelt A, Siedlar M, Frankenberger M, Frankenberger B, Espevik T, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The proinflammatory CD14+CD16+DR++ monocytes are a major source of TNF. J Immunol 168: 3536–3542, 2002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth S, Florida-James GD, McFarlin BK, Spielmann G, O’Connor DP, Simpson RJ. The impact of acute strenuous exercise on TLR2, TLR4 and HLA.DR expression on human blood monocytes induced by autologous serum. Eur J Appl Physiol 110: 1259–1268, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 14: 377–381, 1982. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caricilli AM, Nascimento PH, Pauli JR, Tsukumo DM, Velloso LA, Carvalheira JB, Saad MJ. Inhibition of Toll-like receptor 2 expression improves insulin sensitivity and signaling in muscle and white adipose tissue of mice fed a high-fat diet. J Endocrinol 199: 399–406, 2008. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werts C, Tapping RI, Mathison JC, Chuang TH, Kravchenko V, Saint Girons I, Haake DA, Godowski PJ, Hayashi F, Ozinsky A, Underhill DM, Kirschning CJ, Wagner H, Aderem A, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ. Leptospiral lipopolysaccharide activates cells through a TLR2-dependent mechanism. Nat Immunol 2: 346–352, 2001. doi: 10.1038/86354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dasu MR, Devaraj S, Park S, Jialal I. Increased Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation and TLR ligands in recently diagnosed Type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care 33: 861–868, 2010. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasu MR, Devaraj S, Zhao L, Hwang DH, Jialal I. High glucose induces Toll-like receptor expression in human monocytes: mechanism of activation. Diabetes 57: 3090–3098, 2008. doi: 10.2337/db08-0564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasu MR, Ramirez S, Isseroff RR. Toll-like receptors and diabetes: a therapeutic perspective. Clin Sci (Lond) 122: 203–214, 2012. doi: 10.1042/CS20110357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Graaf R, Kloppenburg G, Kitslaar PJHM, Bruggeman CA, Stassen F. Human heat shock protein 60 stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Microbes Infect 8: 1859–1865, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fadini GP, de Kreutzenberg SV, Boscaro E, Albiero M, Cappellari R, Kränkel N, Landmesser U, Toniolo A, Bolego C, Cignarella A, Seeger F, Dimmeler S, Zeiher A, Agostini C, Avogaro A. An unbalanced monocyte polarisation in peripheral blood and bone marrow of patients with type 2 diabetes has an impact on microangiopathy. Diabetologia 56: 1856–1866, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2918-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field CJ, Gougeon R, Marliss EB. Circulating mononuclear cell numbers and function during intense exercise and recovery. J Appl Physiol (1985) 71: 1089–1097, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn MG, McFarlin BK. Toll-like receptor 4: link to the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 34: 176–181, 2006. doi: 10.1249/01.jes.0000240027.22749.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabriel H, Urhausen A, Kindermann W. Circulating leucocyte and lymphocyte subpopulations before and after intensive endurance exercise to exhaustion. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 63: 449–457, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF00868077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibala MJ, Little JP, Macdonald MJ, Hawley JA. Physiological adaptations to low-volume, high-intensity interval training in health and disease. J Physiol 590: 1077–1084, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gleeson M, McFarlin B, Flynn M. Exercise and Toll-like receptors. Exerc Immunol Rev 12: 34–53, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golovkin AS, Matveeva VG, Kudryavtsev IV, Chernova MN, Bayrakova YV, Shukevich DL, Grigoriev EV. Perioperative dynamics of TLR2, TLR4, and TREM-1 expression in monocyte subpopulations in the setting of on-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. ISRN Inflamm 2013: 817901, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/817901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen JB, Wilsgård L, Osterud B. Biphasic changes in leukocytes induced by strenuous exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 62: 157–161, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF00643735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoaglin DC, Iglewicz B. Fine-tuning some resistant rules for outlier labeling. J Am Stat Assoc 82: 1147–1149, 1987. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1987.10478551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Innes D, Cameron D, Farquhar A, Tildesley H, Green L, Fraser T. The Kelowna Diabetes Program: bridging the gap between testing guidelines and reality. Can J Diabetes 32: 107–113, 2008. doi: 10.1016/S1499-2671(08)22007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jelleyman C, Yates T, O’Donovan G, Gray LJ, King JA, Khunti K, Davies MJ. The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 16: 942–961, 2015. doi: 10.1111/obr.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadoglou NP, Perrea D, Iliadis F, Angelopoulou N, Liapis C, Alevizos M. Exercise reduces resistin and inflammatory cytokines in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 30: 719–721, 2007. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptor function and signaling. J Allergy Clin Immunol 117: 979–987, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karstoft K, Winding K, Knudsen SH, Nielsen JS, Thomsen C, Pedersen BK, Solomon TPJ. The effects of free-living interval-walking training on glycemic control, body composition, and physical fitness in Type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 36: 228–236, 2013. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasapis C, Thompson PD. The effects of physical activity on serum C-reactive protein and inflammatory markers: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol 45: 1563–1569, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohut ML, McCann DA, Russell DW, Konopka DN, Cunnick JE, Franke WD, Castillo MC, Reighard AE, Vanderah E. Aerobic exercise, but not flexibility/resistance exercise, reduces serum IL-18, CRP, and IL-6 independent of β-blockers, BMI, and psychosocial factors in older adults. Brain Behav Immun 20: 201–209, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komura T, Sakai Y, Honda M, Takamura T, Matsushima K, Kaneko S. CD14+ monocytes are vulnerable and functionally impaired under endoplasmic reticulum stress in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 59: 634–643, 2010. doi: 10.2337/db09-0659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurt-Jones EA, Mandell L, Whitney C, Padgett A, Gosselin K, Newburger PE, Finberg RW. Role of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in neutrophil activation: GM-CSF enhances TLR2 expression and TLR2-mediated interleukin 8 responses in neutrophils. Blood 100: 1860–1868, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Tits LJ, Michel MC, Grosse-Wilde H, Happel M, Eigler FW, Soliman A, Brodde OE. Catecholamines increase lymphocyte β2-adrenergic receptors via a β2-adrenergic, spleen-dependent process. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 258: E191–E202, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lancaster GI, Khan Q, Drysdale P, Wallace F, Jeukendrup AE, Drayson MT, Gleeson M. The physiological regulation of Toll-like receptor expression and function in humans. J Physiol 563: 945–955, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langjahr P, Díaz-Jiménez D, De la Fuente M, Rubio E, Golenbock D, Bronfman FC, Quera R, González MJ, Hermoso MA. Metalloproteinase-dependent TLR2 ectodomain shedding is involved in soluble Toll-like receptor 2 (sTLR2) production. PLoS One 9: e104624, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Little JP, Gillen JB, Percival ME, Safdar A, Tarnopolsky MA, Punthakee Z, Jung ME, Gibala MJ. Low-volume high-intensity interval training reduces hyperglycemia and increases muscle mitochondrial capacity in patients with Type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 111: 1554–1560, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00921.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Little JP, Jung ME, Wright AE, Wright W, Manders RJF. Effects of high-intensity interval exercise versus continuous moderate-intensity exercise on postprandial glycemic control assessed by continuous glucose monitoring in obese adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 39: 835–841, 2014. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, Lindley MR, Mastana SS, Nimmo MA. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 607–615, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nri3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maud PJ, Foster C. Physiological Assessment of Human Fitness. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nieman DC. Exercise, upper respiratory tract infection, and the immune system. Med Sci Sports Exerc 26: 128–139, 1994. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oberlin DJ, Mikus CR, Kearney ML, Hinton PS, Manrique C, Leidy HJ, Kanaley JA, Rector RS, Thyfault JP. One bout of exercise alters free-living postprandial glycemia in type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46: 232–238, 2014. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182a54d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliveira M, Gleeson M. The influence of prolonged cycling on monocyte Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 expression in healthy men. Eur J Appl Physiol 109: 251–257, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ostrowski K, Rohde T, Asp S, Schjerling P, Pedersen BK. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine balance in strenuous exercise in humans. J Physiol 515: 287–291, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.287ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol Rev 88: 1379–1406, 2008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.90100.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen BK, Hoffman-Goetz L. Exercise and the immune system: regulation, integration, and adaptation. Physiol Rev 80: 1055–1081, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pickup JC, Mattock MB, Chusney GD, Burt D. NIDDM as a disease of the innate immune system: association of acute-phase reactants and interleukin-6 with metabolic syndrome X. Diabetologia 40: 1286–1292, 1997. doi: 10.1007/s001250050822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson E, Durrer C, Simtchouk S, Jung ME, Bourne JE, Voth E, Little JP. Short-term high-intensity interval and moderate-intensity continuous training reduce leukocyte TLR4 in inactive adults at elevated risk of type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 119: 508–516, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00334.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rönnemaa T, Mattila K, Lehtonen A, Kallio V. A controlled randomized study on the effect of long-term physical exercise on the metabolic control in Type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Med Scand 220: 219–224, 1986. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb02754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rullman E, Olsson K, Wågsäter D, Gustafsson T. Circulating MMP-9 during exercise in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 1249–1255, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabroe I, Prince LR, Jones EC, Horsburgh MJ, Foster SJ, Vogel SN, Dower SK, Whyte MK. Selective roles for Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 in the regulation of neutrophil activation and life span. J Immunol 170: 5268–5275, 2003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I, Yin H, Flier JS. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 116: 3015–3025, 2006. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simpson RJ, McFarlin BK, McSporran C, Spielmann G, ó Hartaigh B, Guy K. Toll-like receptor expression on classic and pro-inflammatory blood monocytes after acute exercise in humans. Brain Behav Immun 23: 232–239, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smits HH, Grünberg K, Derijk RH, Sterk PJ, Hiemstra PS. Cytokine release and its modulation by dexamethasone in whole blood following exercise. Clin Exp Immunol 111: 463–468, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Starkie RL, Angus DJ, Rolland J, Hargreaves M, Febbraio MA. Effect of prolonged, submaximal exercise and carbohydrate ingestion on monocyte intracellular cytokine production in humans. J Physiol 528: 647–655, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stewart LK, Flynn MG, Campbell WW, Craig BA, Robinson JP, McFarlin BK, Timmerman KL, Coen PM, Felker J, Talbert E. Influence of exercise training and age on CD14+ cell-surface expression of Toll-like receptor 2 and 4. Brain Behav Immun 19: 389–397, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stich V, de Glisezinski I, Berlan M, Bulow J, Galitzky J, Harant I, Suljkovicova H, Lafontan M, Rivière D, Crampes F. Adipose tissue lipolysis is increased during a repeated bout of aerobic exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 88: 1277–1283, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terada T, Friesen A, Chahal BS, Bell GJ, McCargar LJ, Boulé NG. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of high-intensity interval training in Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 99: 120–129, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Timmerman KL, Flynn MG, Coen PM, Markofski MM, Pence BD. Exercise training-induced lowering of inflammatory (CD14+CD16+) monocytes: a role in the anti-inflammatory influence of exercise? J Leukoc Biol 84: 1271–1278, 2008. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0408244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Triantafilou M, Gamper FG, Haston RM, Mouratis MA, Morath S, Hartung T, Triantafilou K. Membrane sorting of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2/6 and TLR2/1 heterodimers at the cell surface determines heterotypic associations with CD36 and intracellular targeting. J Biol Chem 281: 31002–31011, 2006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602794200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, Leenen PJ, Liu YJ, MacPherson G, Randolph GJ, Scherberich J, Schmitz J, Shortman K, Sozzani S, Strobl H, Zembala M, Austyn JM, Lutz MB. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood 116: e74–e80, 2010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zwolak A, Słabczyńska O, Semeniuk J, Daniluk J, Szuster-Ciesielska A. Metformin changes the relationship between blood monocyte Toll-like receptor 4 levels and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—ex vivo studies. PLoS One 11: e0150233, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]