Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the antiproliferative effect of the isolated metabolites from Callyspongia siphonella.

Methods:

Different chromatographic methods have been done on the organic extract of the marine sponge aiming at isolating the bioactive metabolites. The cytotoxicity of the isolated compounds has been evaluated against the human colorectal cancer cell line; HCT-116, employing SRB assay. The flow cytometry assay was applied to measure the cell cycle analysis.

Results:

Six metabolites (1–6) were obtained. The compounds 4–6 exhibited IC50 values (μM ± SD) of 95.80± 1.34, 14.8 ± 2.33, and 19.8 ± 3.78, respectively. Cell cycle distribution analysis revealed that sipholenol A (5) and sipholenol L (6) induced G2/M and S phase arrest with concomitant increase in the pre-G cell population. Furthermore, 5 and 6 increased the nuclear expression of the pro-apoptotic protein-cleaved caspase-3 that effectively drives cellular apoptosis via caspase-3-dependent pathway.

Conclusions:

The antiproliferative activity of 5 and 6 can be recognized, at least partly, due to their ability to induce cellular apoptosis.

SUMMARY

Several metabolites were isolated from the marine sponge Callyspongia siphonella. Sipholenol A and sipholenol L exhibited effective cytotoxicity against HCT-116 cells. The observed cytotoxicity involves induction of cellular apoptosis.

Abbreviation used: A549 (human lung carcinoma), Caco-2 (Human ColonCarcinoma), CHCl3 (Chloroform), HCT 116 (Human Colon Carcinoma), HepG2 (Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma), HT-29 (Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma), MCF-7 (Michigan Cancer Foundation-7; Human Breast Adenocarcinoma), MeOH (Methanol), NMR Nuclear Magnetic Resonance), PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline), PC-3 (Human Prostate Cancer), PTLC (Preparative Thin Layer Chromatography), RPMI-1640 (Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium), TLC (ThinLayer Chromatography).

Keywords: Antiproliferative, Callyspongia siphonella, HCT-116, marine, sponge

INTRODUCTION

The Red Sea sponge Callyspongia siphonella (Family Callyspongiidae) was collected by scuba diving around Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. It is considered a potential source of different molecular architectural metabolites which belong to different classes, including steroids, triterpene, and acetylenic derivatives.[1,2,3] The antimigratory effect of sipholenol A and its analogs against the highly metastatic human breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 in a wound healing assay were previously reported.[4,5] Three sipholanetriterpenes enhanced the cytotoxicity of several P-gp substrate anticancer drugs.[6,7] We have also reported a cytotoxic activity of sipholenone A, sipholenol A, and sipholenol L against A549 (Human Lung Carcinoma), MCF-7(Human Breast Adenocarcinoma) and PC-3 (Human Prostate Cancer).[8] Further, we have shown an observable activity against Caco-2, and HT-29 and HepG2 cells.[9] In continuation of our phytochemical and biological evaluation of C. siphonella, the present study was designed to explore the potential cytotoxicity of its bioactive metabolites against the human colorectal cancer cells HCT-116.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General experimental procedures

Sulforhodamine-B was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). RPMI-1640 medium, heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, streptomycin, penicillin, and other cell culture materials were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Other reagents were of the highest analytical grade.

Sponge material

The colonial tube-sponge, previously Siphonochalina siphonella, and was renamed by Dr. Rob van Soest to be C. siphonella, family: Callyspongiidae. Holotype; Callyspongia was collected from the Red Sea coast, North of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (21°29’33”N 39°11’25”E), at a depth of 5-10 m (January, 2013). The sample was collected and identified by Dr. Yahia Folos, Faculty of Marine Sciences, King Abdulaziz University. After collection, this material was immediately subjected to extraction. A voucher specimen (SC-2013-10) was deposited in the Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The colonial tube-sponge has viviparous; light beige in color, as several tubes fused together, and have a soft consistency due to the absence of spicules.

Extraction and isolation of compounds

The dried sponge material (105 g) was extracted with 3 × 8 l of CH2 Cl2/MeOH (1:1, v/v), 24 h for each batch, at room temperature. The extract was concentrated under reduced pressure to provide 22.75 g of viscous oil. The residue was partitioned between diethyl ether and water, the organic layer was homogenized with small amounts of aluminum oxide and CHCl3, poured onto an aluminum oxide column (diameter 50 cm; length 100 cm), which was eluted with gradients from n-hexane to diethyl ether and from n-hexane to ethyl acetate; 200 fractions (~20 ml each) were collected. Similar fractions were pooled, according to their TLC behavior, into eight samples (P-A to P-I), employing a UV254 lamp and/or 50% sulfuric acid in ethanol as spraying reagent for detection of spots. All compounds were purified by preparative TLC (PTLC) and re-purified by employing Sephadex LH-20 (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), if appropriate, using a mixture of MeOH/CHCl3 (9:1). Sample P-B (n-hexane/diethyl ether, 6:4; 25 mg) was purified by PTLC on aluminum oxide using n-hexane/diethyl ether (7:3), yielding 1 (23 mg). Sample P-C (n-hexane/diethyl ether, 4:6; 15 mg) was purified by PTLC on aluminum oxide using n-hexane/diethyl ether (1:1), yielding two compounds, i.e., 2 (Rf 0.45; 3 mg) and 3 (Rf 0.31; 5 mg). Sample P-C (n-hexane/diethyl ether, 5:5; 100 mg) was purified by PTLC on aluminum oxide using n-hexane/diethyl ether (6:4), yielding 4 (3 mg). Sample P-B (n-hexane/diethyl ether, 4:6; 10 mg) was purified by PTLC on aluminum oxide using n-hexane/diethyl ether (7:3), yielding 5 (23 mg). Sample P-C (n-hexane/diethyl ether, 4:6; 15 mg) was purified by PTLC on aluminum oxide using n-hexane/diethyl ether (1:1), yielding two compounds, i.e. 6 (Rf 0.45; 2 mg).

Cell culture

Cell lines were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Cairo, Egypt). HCT-116 (human colon cancer cell lines) was maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, 100 units/mL of penicillin and 10% of heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% (v/v) CO2 at 37°C.

Antiproliferation assay

The sulforhodamine-B (SRB) assay was used to assess the potential antiproliferative effects of compounds at different serial concentrations for 72 h. Then, cells were treated as previously described.[13]

Cell cycle analysis

The HCT-116 cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 106 cells/mL RPMI-1640 mediumin T-75 flasks for 24 h and then exposed to the respective compounds at their IC50 concentration for 24 h. Cell cycle progression was assessed using DNA flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) exploiting CELLQUEST software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). The method is based on univariate analysis of cellular DNA content following cell staining with propidium iodide (PI).[14]

Immunocytochochemical staining

Cells were cultured on sterile cover slips (22 mm2; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) in sterile six well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. After 24 h, cells were exposed to the respective test compound at its IC50 concentration in fresh medium for 24 h. At the end of the exposure, cells attached to the cover slips were washed with PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline), and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.01% Tween 20 (TBST) for 10 min, and blocked for 1 h with 5% goat serum in TBST. Fixed cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with cyclin D1 rabbit monoclonal antibodies (mAb), cyclin B1 rabbit mAb or cleaved caspase-3 rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) at a dilution of 1:500 in blocking solution, followed by secondary anti-mouse Alexa fluor-488 (Invitrogen) and Cy3-goat anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA, USA) at 1:1000 dilution in the blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. 4’,6’-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as nuclear counter stain. The cover slips with attached cells were then mounted on a glass slide with antifade mounting medium and viewed with a Leica epifluorescence microscope DM 5500 B (Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) at a magnification of 60 ×, and data were captured digitally and quantified using the software provided with the microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey-Kramer as a posthoc test. The 0.05 level of probability was used as the criterion of significance, the statistical analysis and the Graphs were created using Graph Pad Prism software version 5 (Graph Pad Software Inc, CA, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

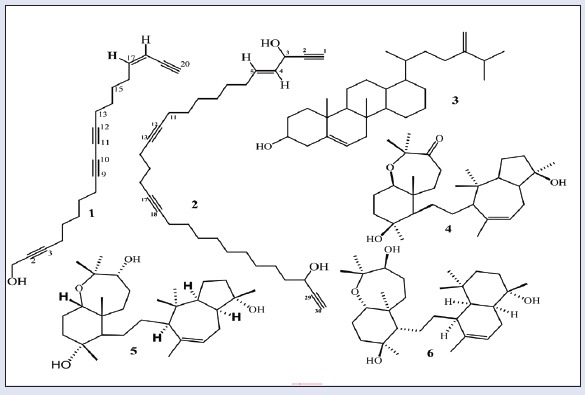

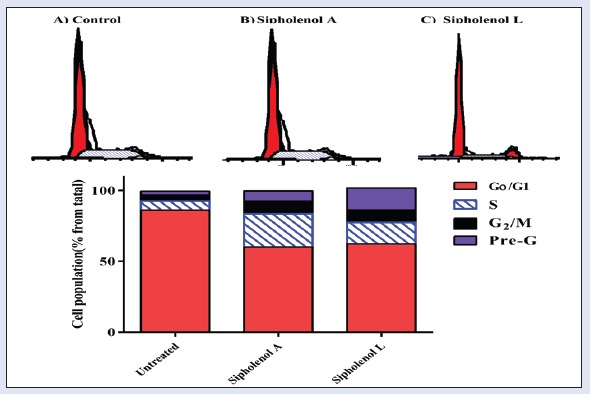

Six metabolites-callyspongenol D (1), callyspongendiol (2),[10] ergosta-5, 24 (28) dien-3β-ol (3),[13] sipholenone A (4), sipholenol A (5),[12] and sipholenol L (6)[2] have been identified [Figure 1]. Chemical structures were determined by comparing NMR spectra with reported data.[10,11,12] The antiproliferative effects of all compounds were evaluated against human colon cancer cells (HCT-116) by employing SRB assay. IC50 (μM ± SD) values of 4-6 were 95.8 ± 1.34, 14.8 ± 2.33, and 19.8 ± 3.78, respectively, whereas compounds 1-3 showed IC50 values more than 100 μM. Siphenone A (4), sipholenol A (5), and sipholenol L (6) showed moderate activity against HCT-116 cells with IC50 values of 14.8 ± 2.33 and 19.8 ± 3.78 μM, respectively, compared to 6.0 ± 0.02 μM for doxorubicin. Based on these data, the activity of compounds 5 and 6 were further substantiated via assessing possible underlying mechanisms. The preliminary mechanism of action of the active compounds was evaluated by assessing cell cycle phases using DNA flow cytometry. The data in Figure 2 revealed that exposure of cells to both compounds in their IC50 for 24 h resulted in an interference with the normal cell cycle distribution. The two compounds significantly increased the proportion of cells in pre-G phase for 2.57- and 5-folds, respectively, compared to control. Accumulation of cells in pre-G phase, which was confirmed by the presence of a pre-G peak in the cell cycle profile analysis, may result from degradation or fragmentation of the genetic materials, indicating a possible role of apoptosis in these compound-induced cancer cell deaths. Furthermore, both compounds increased significantly G2/M-phase and S-phase cell populations with subsequent decrease in G1 cell population, indicating S and G2/M arrest [Figure 4].

Figure 1.

Structures of the isolated compounds (1-6)

Figure 2.

Effect of Callyspongia siphonella triterpenoids on the cell cycle of HCT-116 cells. Cells were exposed to sipholenol-A (b) and sipholenol-L (c) for 24 h and compared to control cells (a). Cell cycle phases were determined by DNA cytometry and plotted as percent of total events (n = 3)

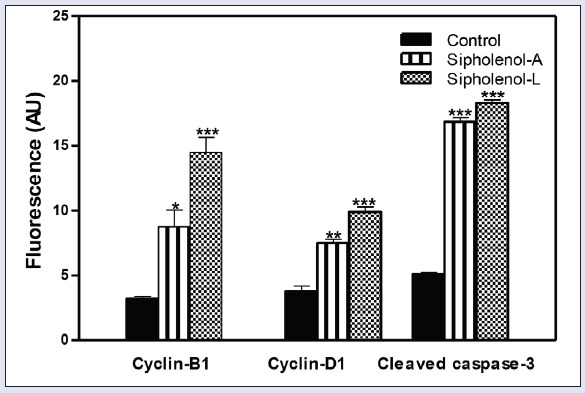

Figure 4.

Quantitation of fluorescence intensity sipholenol-A and sipholenol-L on cylin-B1, cyclin-D1, and cleaved caspase-3. AU: arbitrary units. *denotes significantly different from control at P < 0.05.

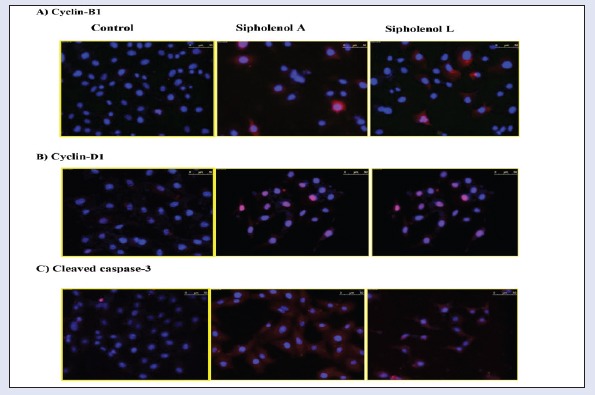

To further investigate the mechanism of the observed triterpenoidal-induced cell death, expression of cyclin-B1, cleaved caspase-3, and cyclin-D1 were assessed using immune-fluorescence assay after exposing HCT-116 cells to sipholenol-A and sipholenol-L in IC50 concentration for 24 h [Figure 3]. Both compounds significantly increased the expression of cyclin-B1 with concomitant accumulation in the nucleus. Localization of cyclin B1 to the nucleus is among the factors determining the cellular decision to undergo apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Additionally, expression and nuclear localization of cleaved caspase-3 is an important apoptosis marker. Immunocytochemical assessment of cleaved caspase-3 showed significant overexpression after treatment with sipholenol-A, and sipholenol-L. Taken together, this explains the significant increase in cells in pre-G phase detected by DNA flow cytometry. On the other hand, sipholenol-A (5) and sipholenol-L (6) significantly increased the expression of cyclin-D1. Cyclin-D1 is a cell cycle check protein that can form a complex with different cyclin-dependent kinases such as Cdk2, 4, 5, and 6, allowing cells ultimately to proceed from G0/G1 phase to S-phase [Figure 4]. Thus the ability of both compounds to induce significant decrease in cell G0/G1-phase cell population and significant increase in S-phase population might be attributed to the overexpression of cyclin-D1 [Figure 2].

Figure 3.

Effect of sipholenol-A and sipholenol-L at their respective IC50 concentration on the levels of cell cycle regulatory proteins in HCT-116 cells after 24 h of incubation. Cyclin-B1, cyclin-D1, and cleaved caspase-3 were assessed inmmunocytochemically (red), and cells were counterstained with nuclear DAPI stain (blue)

CONCLUSIONS

Six metabolites (1-6) have been obtained from the organic extract of C. siphonella. All compounds showed moderate to weak cytotoxic activity against HCT-116, and the moderate cytotoxic activity was observed with 4-6 as IC50 values (μM ± SD) were 95.8 ± 1.34, 14.8 ± 2.33, and 19.8 ± 3.78, respectively. The effect of the tested compounds on cell cycle distribution and their ability to induce apoptosis were investigated. Cell cycle analysis revealed that sipholenol-A (5) and sipholenol-L (6) induced G2/M and S phase cell cycle arrest with concomitant increase in the pre-G cell population, indicating a possible role of apoptosis. Furthermore, sipholenol-A (5) and sipholenol-L (6) increased nuclear expression of the pro-apoptotic protein-cleaved caspase-3 that effectively drives HCT-116 cellular apoptosis via caspase-3-dependent pathway. In conclusion, the observed antiproliferative activity of 5 and 6 can be attributed, at least partly, to their ability to induce cellular apoptosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

The project was funded by the Saudi Basic Industries Corroboration (SABIC) and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. MS/14/332/1433. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks SABIC and DSR technical and financial support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Thanks go to Biologist Yahia Folos, Marine Biology Department, Faculty of Marine Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, for collection and identification of the sponge sample.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jain S, Laphookhieo S, Shi Z, L-W Fu, Akiyama S-I, Chen Z-S, et al. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by sipholanetriterpenoids. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:928–31. doi: 10.1021/np0605889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain S, Abraham I, Carvalho P, Y-H Kuang, Shaala LA, Youssef DTA. Sipholanetriterpenoids: Chemistry, reversal of ABCB1/P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance, and pharmacophore modeling. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1291–8. doi: 10.1021/np900091y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Youssef DTA, Ibrahim AK, Khalifa SI, Mesbah MK, Mayer AMS, van Soest RWM. New anti-inflammatory sterols from the Red Sea sponges Scalarispongia aqabaensis and Callyspongia siphonella. Nat Prod Commun. 2010;5:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham I, Jain S, C-P Wu, Khanfar MA, Kuang Y, Dai C-L, et al. Marine sponge-derived sipholanetriterpenoids reverse P-glycoprotein (ABCB1)-mediated multidrug resistance in cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foudah AI, Jain S, Busnena BA, El Sayed KA. Optimization of marine triterpenesipholenols as inhibitors of breast cancer migration and invasion. Chem Med Chem. 2013;8:497–510. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Y-K Zhang, Y-J Wang, Vispute SG, Jain S, Chen Y, et al. Esters of the marine-derived triterpenesipholenol A reverse P-GP-mediated drug resistance. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:2267–86. doi: 10.3390/md13042267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foudah AI, Sallam AA, Akl MR, El Sayed KA. Optimization, pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR studies of sipholanes as breast cancer migration and proliferation inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;73:310–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angawi RF, Saqer E, Abdel-Lateff A, Badria FA, S-EN Ayyad. Cytotoxic neviotanetriterpene-type from the red sea sponge Siphonochalina siphonella. Pharmacogn Mag. 2014;10:334–41. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.133292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel-Lateff A, Al-Abd AM, Alahdal AM, Alarif WM, S-EN Ayyad, Al-Lihaibi SS, et al. Antiproliferative effects of triterpenoidal derivatives, obtained from the marine sponge Siphonochalina sp., on human hepatic and colorectal cancer cells. J Biosci. 2016;71:29–35. doi: 10.1515/znc-2015-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.S-EN Ayyad, Angawy R, Alarif WM, Saqer EA, Badria FA. Cytotoxic polyacetylenes from the Red Sea sponge Siphonochalina siphonella. Z Naturforsch C. 2014;69:117–23. doi: 10.5560/znc.2013-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nes WD, Stafford AE. Evidence for metabolic and functional discrimination of sterols by Phytophthora cactorum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:3227–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.11.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmely S, Kashman Y. The sipholanes, a novel group of triterpenes from the marine sponge Siphonochalina siphonella. J Org Chem. 1983;48:3517–25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vichai V, Kirtikara K. Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay for cytotoxicity screening. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1112–6. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pozarowski P, Darzynkiewicz Z. Analysis of cell cycle by flow cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;281:301–11. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-811-0:301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]