Abstract

Streptococcus anginosus group pericarditis is rare. A 24-year-old male soldier presented for care at a military clinic in Afghanistan with shock and cardiac tamponade requiring emergent pericardial drainage and aeromedical evacuation. We review the patient’s case, the need for serial pericardial drainage, and the available literature on this disorder.

Keywords: cardiac tamponade, Operation Enduring Freedom, pericarditis, Streptococcus anginosus

CASE REPORT

A 24-year-old male US soldier presented for care at a military clinic at Kandahar Airfield, Afghanistan, for evaluation of 2 days of left-sided neck pain, nausea, and rapidly progressive orthopnea over 2 hours. His pain had begun as a dull ache, constant in nature, and gradually worsened until the onset of the nausea and orthopnea on the day of presentation. He had no significant past medical or surgical history and took no routine medications. He was initially normotensive and afebrile but tachycardic (131 beats/minute) and tachypneic (36 breaths/minute). Laboratory studies obtained during initial evaluation revealed a leukocyte count of 28000 cells/mm3 (62% band forms). He was immediately referred to the regional trauma receiving hospital for further care.

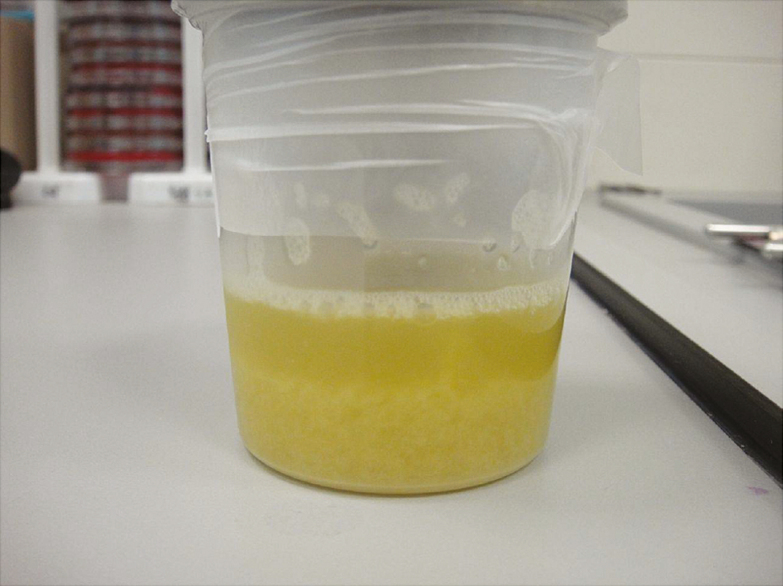

Examination in the trauma bay revealed jugular venous distension to the angle of the jaw and muffled heart sounds. Computed tomography of the chest demonstrated a large pericardial effusion with partial diastolic collapse of the right ventricle seen on bedside cardiac ultrasonography consistent with tamponade physiology. No evidence of associated mediastinal abscess or other contiguous spread from a site external to the pericardium was observed on imaging. Intravenous ceftriaxone and vancomycin were administered, and the patient was taken to the operating room for an emergent pericardial drainage catheter placement under sonographic guidance, with the drainage of 400 mL of purulent fluid (Figure 1). His periprocedural course was complicated by ventricular tachycardia and hypoxemia.

Figure 1.

Sample of purulent pericardial fluid after emergent drainage.

After placement of a drainage catheter, he rapidly developed septic shock and the acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring vasopressor support with norepinephrine and endotracheal intubation. Analysis of the fluid demonstrated 110000 neutrophils/mm3, protein >300 mg/dL, and glucose <10 mg/dL along with numerous Gram-positive cocci in singles and pairs. He was evacuated the following day by critical care air transport to Bagram Airfield, near Kabul, for ongoing care.

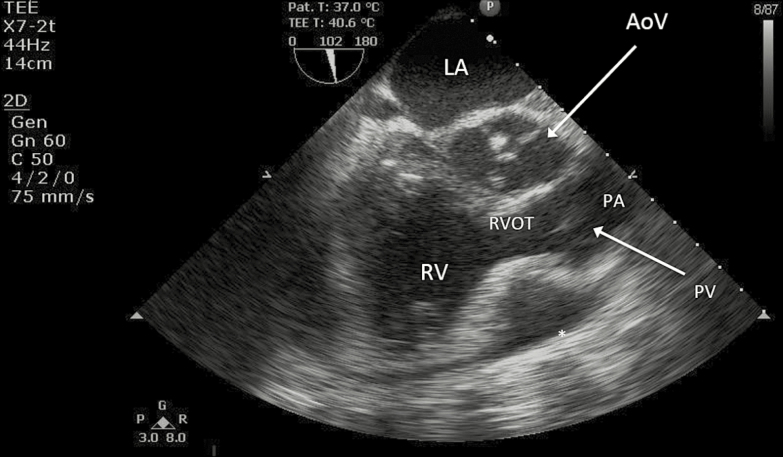

At Bagram, he was noted to have a persistently elevated central venous pressure of 22–24 mmHg and reaccumulation of pericardial fluid with the development of loculations that limited ongoing drainage via the indwelling drain. He developed recurrent tamponade physiology, confirmed by transeophageal echocardiography (Figure 2), despite attempted drainage facilitation using intrapericardial tenecteplase (15 mg). A subxiphoid transesophageal echocardiographic-guided pericardial window and placement of an additional large-bore pericardial drain was performed, with significant improvement in his hemodynamics.

Figure 2.

Transesophageal echocardiogram at Bagram Airfield, revealing a persistent loculated pericardial effusion (marked with an asterix) with diastolic collapse of the right ventricular outflow tract. AoV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; PA, main pulmonary artery; PV, pulmonic valve; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract.

He was subsequently transported on the third day after initial presentation to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Germany, where cultures of his pericardial fluid demonstrated Streptococcus anginosus on conventional blood agar plates. Ceftriaxone was continued, and he was weaned from mechanical ventilation and transported back to the United States where a second pericardial window and large-bore pericardial drain were placed 9 days after his initial presentation. A total of 6 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone was administered, with the remainder of his course complicated by atrial fibrillation that subsequently resolved. Six months later, he had returned to his baseline state of health and resumed normal activity.

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic pericarditis is a rare disorder that may lead to cardiac tamponade, hemodynamic collapse, and death. Before the advent of effective antibiotic therapy, pericarditis was a common complication of pneumonia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae as a result of direct extension from an adjacent pulmonary focus. Effective therapy requires prompt recognition, drainage of pericardial fluid, and bactericidal antibiotics.

Streptococcus anginosus and its related species, Streptococcus intermedius and Streptococcus constellatus, are normally commensals in the human oral, vaginal, and gastrointestinal tracts and collectively form the S anginosus group (SAG). They are facultative, nonmotile anaerobes with variable Lancefield group positivity and form small colonies that may be α-, β-, or nonhemolytic on conventional sheep’s blood agar [1]. Using conventional microbiologic techniques, they may be distinguished from other streptococci through the Voges-Proskauer test for the production of acetoin and 2,3-butanediol, by the hydrolysis of arginine, and their inability to ferment sorbitol [2].

Virulence factors in SAG are not yet well characterized. Molecular mimicry with endothelial selectins present in the host’s vasculature may play a role in the frequency of endovascular infections seen with SAG. Other putative virulence factors are similar to those identified in other streptococci. These include laminin-binding proteins (similar to those seen in Streptococcus agalactiae), polysaccharide capsule production (as with pneumococci), and occasional production of β-hemolysins (similar to streptolysin O in S pyogenes and the pneumolysin produced by pneumococci) [3].

The incidence of SAG infection varies by population and site of infection. The incidence of invasive SAG infection increases with age, with higher risks associated with alcohol abuse in some series [4], but disease has been described in all age groups. Overall, 40%–50% of invasive pyogenic streptococcal disease [5] may be associated with SAG. Among the 3 species, S anginosus has been more closely associated with endocarditis and other endovascular infections [6], as well as abscess formation as a coinfection with Eikenella and other oral anaerobes [7]. In an Israeli series, approximately 75% of SAG infections were community-acquired, with intra-abdominal abscess present in 71 of 202 (35%) and bacteremia in 19 of 202 (9.4%) [8].

Antimicrobial drug resistance is unusual, with most isolates being broadly susceptible to most β-lactams including penicillin. Reduced penicillin susceptibility has been described, similar to other viridans streptococci [9], along with emerging resistance to clindamycin and macrolides [10]. Fluoroquinolones appear active in vitro, but clinical data are currently lacking. Clinical failure has occured in a bacteremic patient with septic shock while receiving daptomycin, although the mechanism of resistance to daptomycin remains unclear [11].

Twenty prior cases of pericarditis due to SAG have been reported in the literature (Table 1) [12–29]. The relative incidence of SAG pericarditis is unknown. In one recent series from the United States, viridans streptococci were identified as the causative pathogens in 8 of 138 (6%) of cases of infectious pericarditis requiring drainage or pericardiectomy [30], potentially including SAG. Risk factors identified in prior cases have included esophageal carcinoma, preceding oral infections, and direct extension from adjacent pleural empyema and pneumonia. Like our patient, all prior cases presented in cardiac tamponade (when cited). Unlike most streptococci, S anginosus produces abscesses that may require repeated drainage; 6 of the 20 previously reported patients required pericardiectomy, whereas an additional 2 patients required intrapericardial thrombolytic therapy due to extensive loculations and adhesions despite percutaneous drainage. Mortality was low in the cases reported, with deaths reported only in patients with advanced malignancy.

Table 1.

Previously Reported Cases of Pericarditis Due to Streptococcus anginosus Group Organismsa

| Age | Gender | Tamponade | IPT | Pericardiectomy | Outcome | Comorbid Conditions | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | M | Y | N | Y | Survived | Pulmonary tuberculosis | Japan |

| 55 | M | Y | N | Y | Survived | Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung | Japan |

| 16 | F | NP | NP | Y | Survived | Direct extension to pericardium from descending mediastinitis after tonsillar abscess |

Italy |

| 69 | F | Y | N | N | Survived | Diabetes mellitus | Japan |

| 54 | M | Y | Y | N | Survived | None stated | Spain |

| 20 | F | Y | N | Y | Survived | Postpartum | USA |

| 71 | F | Y | N | N | Survived | None stated | Belgium |

| 63 | M | Y | N | N | Expired | Metastatic melanoma, complication of TBNA | USA |

| 47 | M | Y | N | N | Expired | Esophageal carcinoma with esophagopericardial fistula | USA |

| 40 | F | NP | Y | N | Survived | Direct extension from pneumonia and mediastinitis | Poland |

| NP | NP | NP | N | NP | NP | Peritonitis due to biliary tract disease | Spain |

| NP | NP | NP | N | NP | NP | Preceding oral infection, pleural empyema | Spain |

| 35 | M | Y | N | N | Survived | Hepatic abscess with direct extension into pericardial and pleural spaces |

Spain |

| 54 | M | Y | N | N | Expired | Esophageal carcinoma with esophagopericardial fistula | Japan |

| 61 | M | Y | N | N | Expired | Esophageal carcinoma with esophagopericardial fistula | Japan |

| 14 | M | Y | N | Y | Survived | Preceding oral infection; drainage complicated by myocardial laceration |

China |

| 56 | F | Y | N | N | Expired | Esophageal carcinoma with esophagopericardial fistula | Japan |

| 17 | F | Y | N | Y | Survived | None stated | USA |

| 62 | M | Y | N | N | Expired | Esophageal carcinoma with esophagopericardial fistula | Spain |

| 23 m | F | Y | N | Y | Survived | Pericardial teratoma | USA |

Abbreviations: F, female; IPT, intrapericardial thrombolytics; M, male; N, no; NP, not provided in the published report; TBNA, transbronchial needle aspiration: Y, yes.

Age is in years, unless followed by “m” (months).

This patient’s care was complicated by his diagnosis in an active combat theater and the development of loculations requiring repeated drainage using catheters of larger diameter than are typical of nonpurulent tamponade. His survival was dependent on the ability of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces to provide robust forward-deployed critical care and surgical capabilities, both on the ground and in the air and including cardiac ultrasonography equipment. In 2012, the NATO Role 3 Multi-National Medical Unit (Kandahar Airfield, Afghanistan) had a medical staff that included specialists in critical care medicine, infectious diseases, anesthesiology, and interventional radiology in addition to general, trauma, cardiothoracic, neurologic, and orthopedic surgeons. Similar capabilities existed at the Craig Joint Theater Hospital at Bagram Airfield, where cardiology consultation was also available. Critical care air transport teams were able to transport this patient and thousands of other critically ill and injured patients from Kandahar to Bagram and thereafter to Landstuhl, Germany and to hospitals in their home countries. Without these capabilities, this patient’s excellent outcome could not have been assured.

CONCLUSIONS

Pyogenic pericarditis due to SAG organisms is a rare but rapidly life-threatening condition and may occur as a community- acquired infection in healthy hosts. Effective treatment requires expeditious drainage of pericardial fluid, effective antibacterial therapy, and comprehensive critical care support. Repeated drainage, intrapericardial thrombolytics, and pericardiectomy may be necessary to achieve cure given the loculated nature of SAG infections.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer. The authors are United States military service members. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. §105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Departments of the Navy, the Army, the Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

Ethical Approval. This manuscript was reviewed and approved for ethical approval by the Naval Medical Center San Diego Institutional Review Board before submission.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Facklam R. What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15:613–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lawrence J, Yajko DM, Hadley WK. Incidence and characterization of beta-hemolytic Streptococcus milleri and differentiation from S. pyogenes (group A), S. equisimilis (group C), and large-colony group G streptococci. J Clin Microbiol 1985; 22:772–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asam D, Spellerberg B. Molecular pathogenicity of Streptococcus anginosus. Mol Oral Microbiol 2014; 29:145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morita E, Narikiyo M, Yokoyama A, et al. Predominant presence of Streptococcus anginosus in the saliva of alcoholics. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2005; 20:362–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laupland KB, Ross T, Church DL, Gregson DB. Population-based surveillance of invasive pyogenic streptococcal infection in a large Canadian region. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006; 12:224–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Junckerstorff RK, Robinson JO, Murray RJ. Invasive Streptococcus anginosus group infection-does the species predict the outcome? Int J Infect Dis 2014; 18:38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clarridge JE, 3rd, Attorri S, Musher DM, et al. Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus anginosus (“Streptococcus milleri group”) are of different clinical importance and are not equally associated with abscess. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:1511–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Siegman-Igra Y, Azmon Y, Schwartz D. Milleri group Streptococcus—a stepchild in the viridans family. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012; 31:2453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tracy M, Wanahita A, Shuhatovich Y, et al. Antibiotic susceptibilities of genetically characterized Streptococcus milleri group strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001; 45:1511–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asmah N, Eberspächer B, Regnath T, Arvand M. Prevalence of erythromycin and clindamycin resistance among clinical isolates of the Streptococcus anginosus group in Germany. J Med Microbiol 2009; 58:222–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palacio F, Lewis JS, 2nd, Sadkowski L, et al. Breakthrough bacteremia and septic shock due to Streptococcus anginosus resistant to daptomycin in a patient receiving daptomycin therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:3639–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reder RF, Raucher H, Cesa M, Mindich BP. Purulent pericarditis caused by Streptococcus anginosus-constellatus. Mt Sinai J Med 1984; 51:295–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Akashi K, Ishimaru T, Tsuda Y, et al. Purulent pericarditis caused by Streptococcus milleri. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:2446–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hirata K, Asato H, Maeshiro M. A case of effusive constrictive pericarditis caused by Streptococcus milleri. Jpn Circ J 1991; 55:154–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Epstein SK, Winslow CJ, Brecher SM, Faling LJ. Polymicrobial bacterial pericarditis after transbronchial needle aspiration. Case report with an investigation on the risk of bacterial contamination during fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992; 146:523–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sánchez-Porto A, Iñigo MA, Rojas E, González-Serrano M. [Fatal Streptococcus anginosus-milleri (Lancefield group F) meningitis in a cocaine addict]. Med Clin (Barc) 1992; 98:199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sagristà-Sauleda J, Barrabés JA, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Purulent pericarditis: review of a 20-year experience in a general hospital. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993; 22:1661–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Muto M, Ohtsu A, Boku N, et al. Streptococcus milleri infection and pericardial abscess associated with esophageal carcinoma: report of two cases. Hepatogastroenterology 1999; 46:1782–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Snyder RW, Braun TI. Purulent pericarditis with tamponade in a postpartum patient due to group F streptococcus. Chest 1999; 115:1746–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marchal LL, Detollenaere M, De Baere HJ. Streptococcus milleri, a rare cause of pericarditis; successful treatment by pericardiocentesis combined with parenteral antibiotics. Acta Clin Belg 2000; 55:222–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roth TC, Schmid RA. Pneumopericardium after blunt chest trauma: a sign of severe injury? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002; 124:630–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salazar González JJ, Sánchez-Rubio Lezcano J, Merchante García P. [Purulent pericarditis with pneumopericardium caused by Streptococcus milleri]. Rev Esp Cardiol 2002; 55:861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaufman J, Thongsuwan N, Stern E, Karmy-Jones R. Esophageal-pericardial fistula with purulent pericarditis secondary to esophageal carcinoma presenting with tamponade. Ann Thorac Surg 2003; 75:288–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tomkowski WZ, Gralec R, Kuca P, et al. Effectiveness of intrapericardial administration of streptokinase in purulent pericarditis. Herz 2004; 29:802–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roccia F, Pecorari GC, Oliaro A, et al. Ten years of descending necrotizing mediastinitis: management of 23 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 65:1716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tokuyasu H, Saitoh Y, Harada T, et al. Purulent pericarditis caused by the Streptococcus milleri group: a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med 2009; 48:1073–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Q, Zi J, Liu F, Li D. Purulent pericarditis caused by a bad tooth. Eur Heart J 2013; 34:862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takayama T, Okura Y, Funakoshi K, et al. Esophageal cancer with an esophagopericardial fistula and purulent pericarditis. Intern Med 2013; 52:243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Presnell L, Maeda K, Griffin M, Axelrod D. A child with purulent pericarditis and Streptococcus intermedius in the presence of a pericardial teratoma: an unusual presentation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 147:e23–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mookadam F, Moustafa SE, Sun Y, et al. Infectious pericarditis: an experience spanning a decade. Acta Cardiol 2009; 64:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]