Abstract

Purpose

Benzalkonium chloride (BAK) is the most commonly used eye drop preservative. Benzalkonium chloride has been associated with toxic effects such as “dry eye” and trabecular meshwork degeneration, but the underlying biochemical mechanism of ocular toxicity by BAK is unclear. In this study, we propose a mechanistic basis for BAK's adverse effects.

Method

Mitochondrial O2 consumption rates of human corneal epithelial primary cells (HCEP), osteosarcoma cybrid cells carrying healthy (control) or Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) mutant mtDNA [11778(G>A)], were measured before and after acute treatment with BAK. Mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis and cell viability were also measured in the BAK-treated control: LHON mutant and human-derived trabecular meshwork cells (HTM3).

Results

Benzalkonium chloride inhibited mitochondrial ATP (IC50, 5.3 μM) and O2 consumption (IC50, 10.9 μM) in a concentration-dependent manner, by directly targeting mitochondrial complex I. At its pharmaceutical concentrations (107–667 μM), BAK inhibited mitochondrial function >90%. In addition, BAK elicited concentration-dependent cytotoxicity to cybrid cells (IC50, 22.8 μM) and induced apoptosis in HTM3 cells at similar concentrations. Furthermore, we show that BAK directly inhibits mitochondrial O2 consumption in HCEP cells (IC50, 3.8 μM) at 50-fold lower concentrations than used in eye drops, and that cells bearing mitochondrial blindness (LHON) mutations are further sensitized to BAK's mitotoxic effect.

Conclusions

Benzalkonium chloride inhibits mitochondria of human corneal epithelial cells and cells bearing LHON mutations at pharmacologically relevant concentrations, and we suggest this is the basis of BAK's ocular toxicity. Prescribing BAK-containing eye drops should be avoided in patients with mitochondrial deficiency, including LHON patients, LHON carriers, and possibly primary open-angle glaucoma patients.

Keywords: mitochondrial complex I, benzalkonium chloride, LHON, glaucoma, preservative

In order to maintain sterility and prevent ocular infections from a contaminated eye drop, the addition of preservatives is mandatory in multidose ophthalmic formulations according to international standards. Of the many available preservatives, benzalkonium chloride (BAK), a quaternary ammonium salt, is the most common preservative used in eye drops.1 Benzalkonium chloride is a mixture of quaternary ammonium compounds with a chemical formula C6H5CH2N(CH3)2(CH2)nCl, where n = 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, or 18. Although the advantage of BAK as an ocular preservative is its amphipathic nature, high water solubility, and superior antimicrobial effects, eye drops containing BAK have been implicated as a cause of ocular adverse effects, including: dry eye, trabecular meshwork degeneration, and ocular inflammation.2–4 Deleterious effects of BAK are not limited to ocular surface. For example, there are two reports of topically applied BAK reaching the posterior eye and optic nerve in a rat model.5,6 In a clinical trial comparing the effects of BAK-containing and preservative-free eye drops, anterior chamber inflammation was reported in response to BAK after 1 month of exposure.7 In spite of indications of mitochondrial injury by BAK over 30 years,8–11 a clear mechanism for its biochemical toxicity has remained elusive.

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is the most common blinding disease linked to a mitochondrial defect.12 Inherited point mutations in mtDNA of complex I subunits cause LHON. Three mutations (i.e., 11778[G>A] [ND4], 3460[G>A] [ND1], and 14484[T>C] [ND6]), make up >90% of LHON cases, and are called “primary mutations.” These three primary mutations cause defects in mitochondrial complex I–driven adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis13 that correlate with the clinical severity of vision loss. Although the mechanism of vision loss in LHON is not clear, loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), optic nerve atrophy, and demyelination are observed.14 However, some carriers of the mutations are not affected (incomplete penetrance), and one proposed basis for this incomplete penetrance is environmental exposures.15 We recently demonstrated that the environmental mitochondrial complex 1 inhibitor, rotenone, further decreases the LHON mitochondria's ability to make ATP.6,16 Since the combined effect of LHON mutation (11778) and rotenone appear to be additive, it is possible that other complex 1 inhibitors may have similar effects to rotenone, when topically applied to eyes with an underlying mitochondrial impairment.

A specific defect in mitochondrial complex 1–driven ATP synthesis has been identified in multiple ocular diseases involving selective death of RGCs. These include LHON, autosomal dominant optic atrophy (ADOA), and primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).17–20 Functional studies have documented mitochondrial complex 1 defects in both lymphocytes21 and trabecular meshwork cells.22 Interestingly, POAG patients with high mitochondrial function appear to be more resistant to high intraocular pressure (IOP)–induced neurodegeneration.23 The trabecular meshwork (TM) is a special ocular tissue that regulates the drainage of aqueous humor from the eye and thus can act as a key modulator of the IOP.24 Any blockage or impairment of TM function can lead to high IOP, the major risk factor for POAG.25 Benzalkonium chloride has been shown to cause trabecular meshwork injury in vitro and in vivo.2 However, the mechanism of TM toxicity was not clearly understood; as seen below in the Results section, BAK causes direct TM toxicity.

A high-throughput screen of a library of 1600 drugs, preservatives, and disinfectants revealed that BAK functionally inhibits mitochondria.16,26 This led us to hypothesize that mitochondrial inhibition of BAK could underlie its observed toxicity in clinical settings. We further hypothesized that the complex 1 inhibitor BAK would cause more dysfunction in the LHON cells with the 11778 complex I mutation,16 as confirmed below in the Results section. The purpose of this study was to understand the basis of BAK's ocular toxicity and to examine whether LHON mutation (11778) compounds BAK's effects on mitochondrial complex 1.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Control and 11778(G>A) LHON mutation carrying osteosarcoma cybrid cells were gifts of Valerio Carelli and Andrea Martinuzzi.16 Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Corning, Inc., Corning, NY, USA) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum (Corning, Inc.), 50 μg/mL uridine and antibiotics (50 units/mL of penicillin/50 μg/mL of streptomycin; Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) under humidified 5% CO2 at 37°C.

The human TM–derived cell line, HTM3, was a gift from Alcon Laboratories.2,27 Trabecular cells were maintained in serum-free DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 4 mM l-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 50 μg/mL gentamicin, under humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C.

Human corneal epithelial progenitor cells were obtained from Zen-Bio, Inc. (Cat# HCEP; Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). These cells were cultured in epithelial culture medium (CnT-Prime; Zen-Bio, Inc.), supplemented with 50 units/mL of penicillin/50 μg/mL of streptomycin (Gibco), and under humidified 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Chemicals

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. unless otherwise specified. We purchased the ATP bioluminescence assay kit from Roche Life Science (ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit CLS II; Indianapolis, IN, USA). We purchased ATP-free adenosine diphosphate from Cell Technology (Fremont, CA, USA). Stock solutions of BAK (Cat# B6295) were prepared using a molecular weight for BAK of 375, as determined by the manufacturer.

Mitochondrial Complex I–Driven ATP Synthesis Measurement Assay (mtCIDAS)

Vehicle and the BAK-treated cells were subjected to mtCIDAS assay as per the protocol reported previously.16 Briefly, the cells were treated for 24 hours with either vehicle or BAK (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 μM). Subsequently, conditioned media were removed and cells were permeabilized using streptolysin O. Permeabilized cells were incubated with a buffer containing complex I substrates for 30 minutes and the mitochondrial ATP production was measured by using the ATP kit (Roche Life Science) following the manufacturer's instruction.

Oxygen Consumption Assay

Mitochondrial O2 consumption rates (OCR) of HCEP, osteosarcoma cybrid cells carrying healthy (control) or 11778 LHON mutant mtDNA were measured with an extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse XF-24; University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA)28,29 and a commercial electrode system (Oxytherm Clarke; Hansatech Instruments, Norfolk, UK).30 For mechanistic studies, the OCR of cybrid cells was measured by the Clarke electrode; cells were suspended in 1 mL of specialized mitochondrial buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 120 mM KCl, 2 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.3% fat-free bovine serum albumin) permeabilized with digitonin.30 Cellular respiration of digitonin-permeabilized cybrid cells was initiated by addition of substrates supplying electrons to mitochondrial complex I (malate/pyruvate). Complex I inhibitors such as rotenone block further transport of electrons to complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome C oxidoreductase) and thus inhibit mitochondrial O2 consumption. In the presence of a complex I inhibitor, complex II (succinate dehydrogenase) substrate, such as succinate, can restore the mitochondrial respiration by supplying electrons to the complex II, bypassing complex I to supply electrons to the complex III. Similarly, complex III inhibitor such as antimycin A inhibits mitochondrial respiration and a mixture of ascorbate and TMPD (N, N, N', N'-tetramethyl-p-phenylebnediamine) restores the mitochondrial O2 consumption by directly supplying electrons to complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase).

Sulforhodamine B Cell Viability Assay

Cells were seeded (50,000 cells/well) in a 96-well poly-D-Lysine coated plate. Cells were treated with either vehicle or BAK at the specified concentrations (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 μM) for 24 hours. Cell viability was measured by the sulforhodamine B method.31 Under normal conditions, the cybrid cells meet their energetic needs from both cytoplasmic glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Forcing cells to depend entirely on mitochondria sensitizes cells to mitochondrial inhibitors.32 To force mitochondrial reliance, we cultured cells in a glucose-free medium supplemented with the mitochondrial bioenergetics substrate, sodium pyruvate (1 mM).

Neutral Red Cell Viability Assay

At subconfluence (80%), TM cells in 96-well microtiter plates were treated with BAK solutions in PBS at 3, 15, 30, 150, 300, and 1500 μM for 15 minutes. We then replaced the BAK solutions with fresh medium and cells were allowed to recover for 24 hours before being exposed to the neutral red (NR) stain (Fluka Chemical Corp., Ronkonkoma, NY, USA). Neutral red, a cationic dye, is incorporated into the lysosomal matrix of viable cells after diffusing through cell membranes. The lysosomal membrane integrity is correlated with cell viability. Briefly, at the end of the 24 hours post-BAK exposure, cells were incubated in 200 μL of NR diluted in DMEM at 50 μg/mL for 3 hours under standard culture conditions, then washed in PBS (1X D-PBS; Gibco), and lysed in a lysis solution composed of 1% acetic acid, 50% ethanol, and 49% H2O, with agitation for 15 minutes. Fluorescence was measured using a sapphire microplate reader (Tecan Instruments, Lyon, France) with excitation and emission wavelengths set to 535 and 600 nm, respectively.

Results

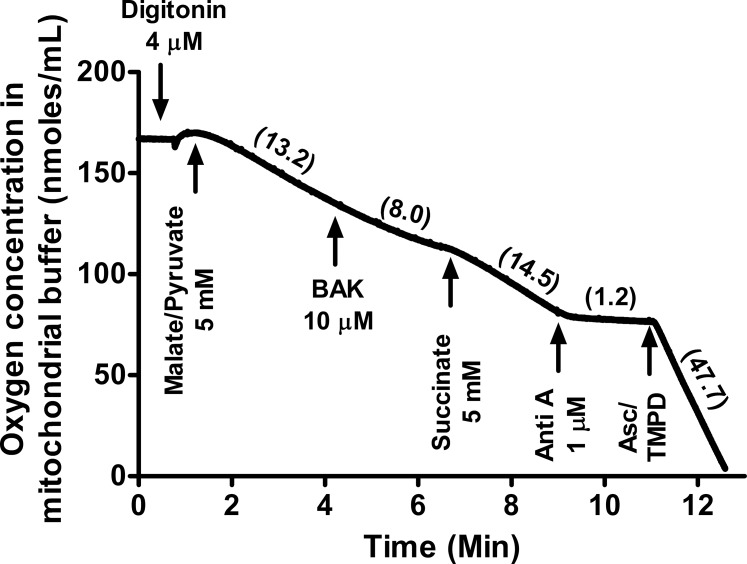

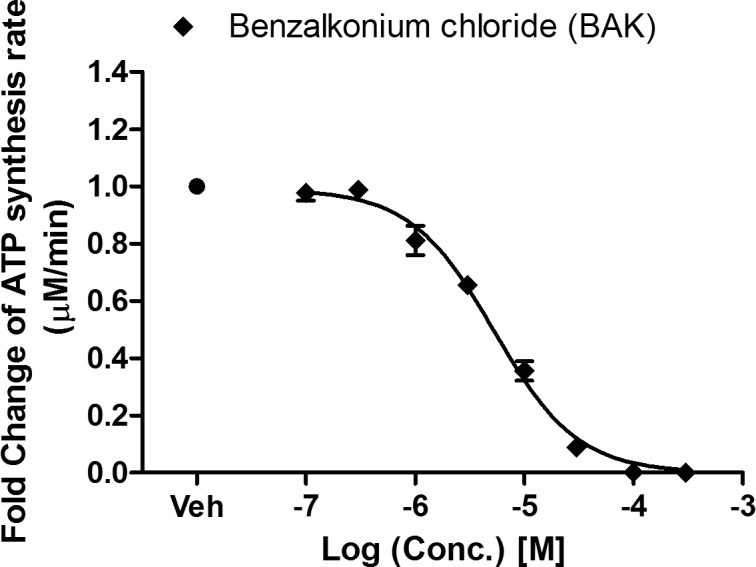

Concentration-Dependent BAK Inhibits Complex I–Driven ATP Synthesis in Cybrid Cells

Benzalkonium chloride inhibited mitochondrial complex I–driven ATP synthesis (mtCIDAS) of cybrid cells in a concentration-dependent manner, in a low micromolar range. The derived IC50 for BAK is 5.3 μM (∼0.0002% vol/vol), is approximately 50-fold lower than the BAK concentrations used in topical ophthalmic formulations (107–667 μM or 0.004–0.025% vol/vol; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Inhibitory effect of BAK on mitochondrial complex I–driven ATP synthesis. Cybrid cells were treated with BAK at increasing concentration (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300 μM), for 24 hours and then the mtCIDAS assay was applied to permeabilized cells. Data are presented as the average fold change of the ATP synthesis rate ± SEM from three independent experiments done in triplicate.

Concentration Dependent BAK Inhibits Mitochondrial Respiration in Cybrid Cells

Mitochondrial O2 consumption is a measurement of mitochondrial electron transport chain activity, which is required for but separate from ATP synthesis. Mitochondrial electron transport inhibitors decrease mitochondrial O2 consumption, and most of them are cytotoxic.33,34 Since BAK was found to inhibit mitochondrial complex I–driven ATP synthesis, and electron transport chain activity is required for ATP synthesis, we hypothesized that BAK would also inhibit mitochondrial O2 consumption. We observed concentration-dependent inhibition of mitochondrial respiration with an IC50 of 10.9 μM (∼0.0004% vol/vol) within 10 minutes of BAK administration (Fig. 2). Benzalkonium chloride inhibited both mitochondrial O2 consumption and ATP synthesis in an overlapping concentration range (1–100 μM). The slightly lower IC50 value for the ATP synthesis assay compared to the mitochondrial O2 consumption assay (5.3 vs. 10.9 μM) may reflect the longer exposure time used in the first assay (24 hours versus 40 minutes).

Figure 2.

Inhibitory effect of BAK on mitochondrial O2 consumption. Cybrid cells were treated with BAK at the specified concentrations (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300 μM). Oxygen consumption rate of cybrid cells was measured four times after BAK addition at 10-minute intervals. The data are presented as the average percentage of basal (untreated) oxygen consumption rate ± SEM from three independent experiments.

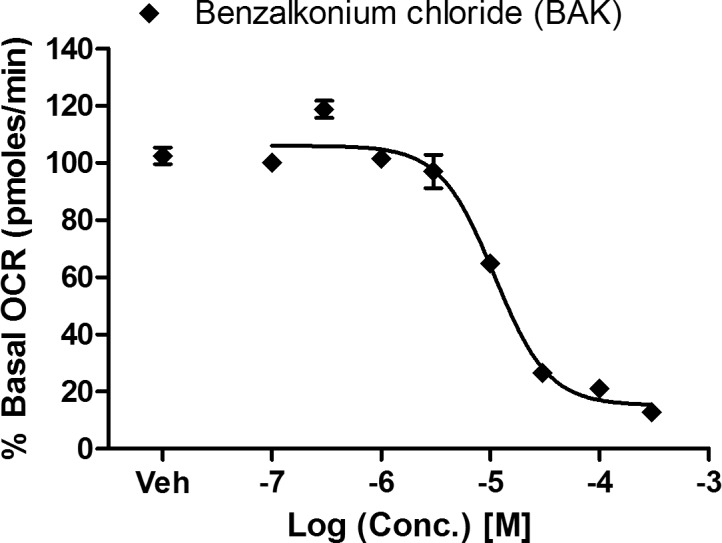

Mechanism of Action: BAK Inhibits Mitochondrial Complex I in Cybrid Cells

Mechanistically, the mitochondrial O2 consumption rate (mitochondrial respiration) reflects the movement of electrons through the electron transport chain (ETC) and final acceptance of the electrons by oxygen. Inhibition of one of the four mitochondrial complexes of the ETC (complex I, II, III, or IV) results in inhibition of mitochondrial O2 consumption. When digitonin-permeabilized cybrid cells respiring on complex I substrates (malate/pyruvate) were treated with BAK (10 μM), O2 consumption was reduced within 3 minutes by almost 40%, compared to that of untreated cells (13.2 nmol/mL versus 8 nmol/mL; Fig. 3). Subsequent addition of succinate restored the mitochondrial O2 consumption rate (14.5 nmol/mL) and overcame BAK-mediated inhibition. These results together unequivocally indicate that BAK specifically inhibits mitochondrial complex 1, thereby causing mitochondrial dysfunction.

Figure 3.

Benzalkonium chloride inhibits mitochondrial O2 consumption at complex I. Cybrid cells were permeabilized with digitonin (4 μM) and respiration was initiated with complex I substrate (malate/pyruvate, 5 mM). Cells were then treated with BAK (10 μM); followed by the complex II substrate (succinate, 5 mM); the complex III inhibitor, antimycin A (Anti A, 1 μM); and finally a mixture of the complex IV substrate Ascorbate (Asc, 5 mM) and TMPD (0.2 mM). Oxygen consumption rates of the cybrid cells suspended in the mitochondrial buffer were measured for 1 minute after each addition and are indicated in parentheses for one representative experiment. The benzalkonium chloride–mediated inhibition of respiration was overcome by the complex II substrate succinate but not complex I substrates, malate/pyruvate.

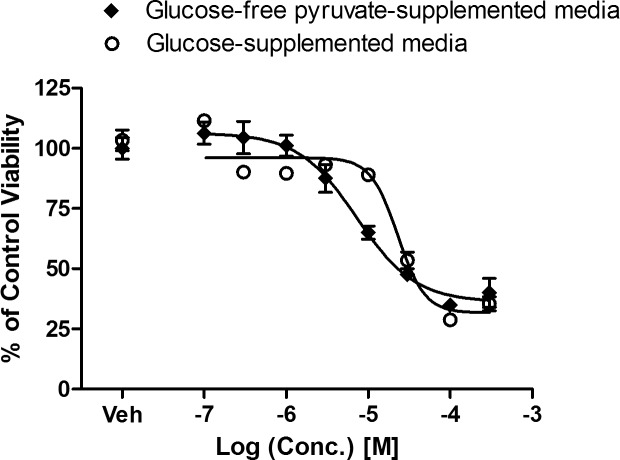

BAK Is More Toxic to Cybrid Cells Dependent on Oxidative Phosphorylation

Due to BAK's mitochondrial inhibitory profile, we hypothesized that BAK's cytotoxicity would be enhanced by a medium that requires higher mitochondrial activity for energy production (i.e., glucose-free pyruvate media). Indeed, BAK showed enhanced toxicity toward cells relying entirely on mitochondria for their energetic needs (Fig. 4). When cybrid cells were cultured in the glucose-free pyruvate supplemented medium and treated with BAK for 24 hours, the IC50 for cytotoxicity was reduced ∼3-fold (IC50 7.2 μM or ∼0.0003% vol/vol) versus glucose medium (IC50 22.8 μM or ∼0.0008% vol/vol).

Figure 4.

Enhanced cytotoxic effect of BAK on cells with enforced mitochondrial metabolism. Cybrid cells were treated with BAK at specified concentration (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300 μM) for 24 hours, and cell viability was measured by sulforhodamine B. Data are presented as average percentage cell viability of vehicle-treated control ± SEM from three independent experiments.

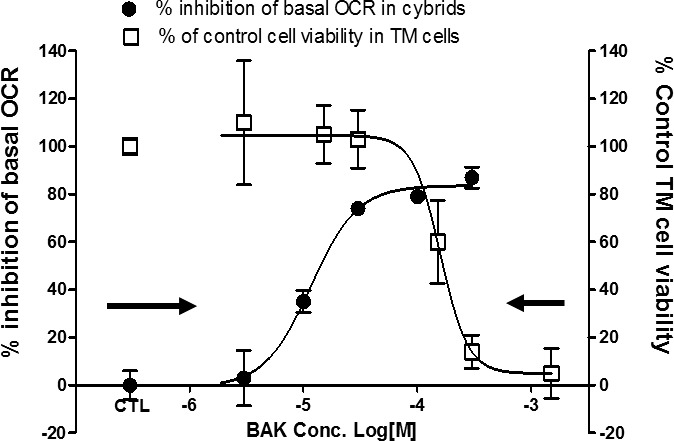

BAK Causes TM Cytotoxicity at Mitochondrial Inhibitory Concentrations in Cybrid and Corneal Epithelial Cells

We further hypothesized that BAK's mitochondrial impairment could cause TM cell death (Fig. 5). The comparison revealed that BAK exposure on a similar time scale, 10 to 15 minutes, both inhibit mitochondrial function in the osteosarcoma cells and drastically decrease TM cell viability within 24 hours. The decrease in TM cell viability was only observed at the higher end of the mitochondrial inhibitory concentration range. Mitochondrial inhibitory concentrations in cybrid cells and TM cell cytotoxic concentrations of BAK were comparable, and because the concentrations inhibiting mitochondrial function are lower than those causing cytotoxicity, we infer that BAK-induced mitochondrial dysfunction causes TM cell injury and death.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the concentrations causing mitochondrial inhibition in cybrid cells and TM cell cytotoxicity. Trabecular meshwork and cybrid cells were treated with BAK as specified and mitochondrial OCR (left axis) and TM cell viability (right axis) were measured. Data are presented as average percent inhibition of basal OCR ± SEM for mitochondrial O2 consumption (black solid circles) and average percent of control cell viability ± SEM for TM cell viability (white squares).

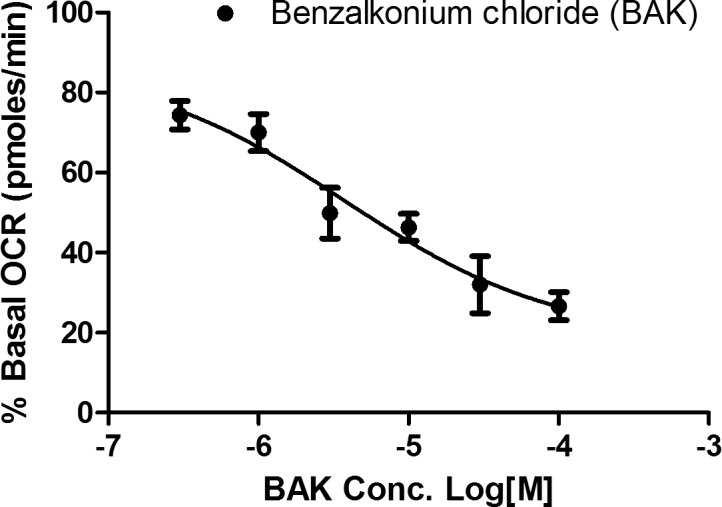

BAK Inhibits Mitochondrial O2 Consumption in HCEP Cells at Physiologically Relevant Concentrations

To confirm BAK's mitochondrial basis of ocular surface toxicity in another ocular cell type, we evaluated the effect of BAK on primary human corneal epithelial progenitor cells. As expected, dose-dependent BAK inhibited mitochondrial O2 consumption in HCEP (IC50: 3.8 μM or ∼0.0002%) within 20 minutes of addition, at 25- to 150-fold lower concentrations than used in eye drops (Fig. 6). This IC50, recorded with HCEP cells, is also 2.5-fold lower than that recorded with cybrid cells (i.e., HCEP cells are more sensitive to the inhibitory effects of BAK than the latter cells).

Figure 6.

Inhibitory effect of BAK on mitochondrial OCR of primary HCEP cells. Human corneal epithelial progenitor cells were treated with BAK at the specified concentration (0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100 μM), and OCR of HCEP was measured five times after BAK addition in 5-minute intervals. Data are presented as the average percentage of basal (untreated) OCR ± SEM from three independent experiments.

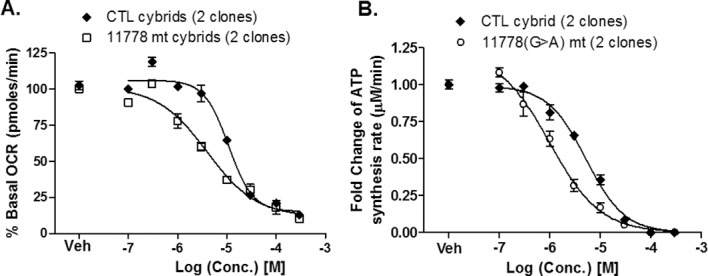

LHON Mutation 11778(G>A) Confers Mitochondrial Sensitivity to BAK

We compared the effects of BAK on LHON 11778 mutant and nonmutant cybrid cells, using both mitochondrial respiration and the mtCIDAS assays. The mutation LHON 11778 conferred significantly increased sensitivity to BAK (nonlinear regression curve fit, GraphPad Prism 5.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) as measured by both mitochondrial respiration (IC50 10.9 μM versus 4.0 μM or ∼0.0004% versus 0.0002% vol/vol) and the mtCIDAS assay (IC50 5.3 μM versus 1.0 μM or ∼0.0002% versus 0.00004%; Fig. 7). The data demonstrate that the mitochondrial complex 1 inhibitory consequences of BAK are further compounded in LHON cells with complex 1 deficits.

Figure 7.

The primary LHON mutation 11778 sensitizes (A) mitochondrial O2 consumption and (B) mtCIDAS to BAK. Both sets of data are presented as the normalized percentage of basal (untreated) rate ± SEM from three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by nonlinear regression curve fit using statistical software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Discussion

Mitochondrial complex 1 deficiency has been demonstrated in three ocular diseases, all involving selective death of retinal ganglion cells, LHON, ADOA, and POAG.13,17,21 We show here that BAK induces mitochondrial dysfunction by potently inhibiting mitochondrial complex I at 50-fold lower concentrations than those used in pharmaceutical ophthalmic formulations. Since BAK is a potent complex I inhibitor, and complex I–driven ATP synthesis is deficient in LHON and ADOA and a subset of POAG patients, it seems that BAK-containing eye drops have the potential to trigger or enhance disease progression and should be used with caution in patients with a family history of these ocular diseases.

It has been reported that BAK present in topically applied eye drops (0.004%–0.025% or 100–600 μM) can reach the optic nerve of rodents and the anterior chamber of human eye.5,7 The trabecular meshwork is a specialized tissue regulating aqueous humor drainage from the eye, and trabecular meshwork defects and decreasing cellularity have been implicated in increasing intraocular pressure and glaucoma.20 Decreases in TM cell numbers have been reported in POAG, and mitochondrial dysfunction has also been proposed as a mechanism for TM injury in this disease.35 A major mechanism for thinning of TM or TM injury in POAG is believed to be mitochondrial dysfunction.36,37 He et al.36 reported that glaucomatous TM cells show an increase in mitochondrial transition pore formation, mitochondrial calcium release, and decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential. Treatment of TM cells with BAK has been shown to cause TM cell death.2 Cytotoxic concentrations of BAK overlap its mitoinhibitory concentrations in primary human corneal epithelial cells (Fig. 6). In addition, inhibition of mitochondrial complex I was previously shown to induce apoptosis.23 Together, these data suggest inhibition of mitochondrial complex I by BAK as the likely mechanism underlying its cytotoxic effects on ocular surface and TM cells.

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy is a disease resulting from inherited defects in mitochondrial complex 1. We recently demonstrated that the 11778(G>A) LHON mutation sensitizes mitochondria to complex I inhibitors.16 Consistent with this idea, BAK shows more inhibition of mitochondrial OCR and mtCIDAS in LHON mutant [11778(G>A)] cells versus nonmutant cybrid cells. Thus, it seems possible that exposure to BAK-containing eye drops in an LHON patient could trigger or speed up LHON progression. This scenario is premised on the assumption that topically applied BAK can reach the posterior segment of the human eye. The data also suggest that the complex I inhibitor BAK should not be administered to the eyes with ongoing complex I deficiency, including LHON carriers and LHON patients, or for that matter, the eyes of patients with other mitochondrial diseases, including ADOA; myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers; mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes; and neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa. Also, since some POAG patients have a demonstrated complex I deficiency,17,21,22 Eye drops containing BAK should be administered to the eyes of POAG patients with caution and proper monitoring. This is necessary due to the increased risk for adverse effects in the POAG patients with mitochondrial deficiency.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 NS077777, R01 EY012245, and P01 AG025532 (GAC).

Disclosure: S. Datta, None; C. Baudouin, None; F. Brignole-Baudouin, None; A. Denoyer, None; G.A. Cortopassi, None

References

- 1. Baudouin C,, Labbe A,, Liang H,, Pauly A,, Brignole-Baudouin F. Preservatives in eyedrops: the good, the bad and the ugly. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010; 29: 312–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baudouin C,, Denoyer A,, Desbenoit N,, Hamm G,, Grise A. In vitro and in vivo experimental studies on trabecular meshwork degeneration induced by benzalkonium chloride (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2012; 110: 40–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aguayo Bonniard A,, Yeung JY,, Chan CC,, Birt CM. Ocular surface toxicity from glaucoma topical medications and associated preservatives such as benzalkonium chloride (BAK). Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2016; 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guzman M,, Sabbione F,, Gabelloni ML,, et al. Restoring conjunctival tolerance by topical nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitors reduces preservative-facilitated allergic conjunctivitis in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 6116–6126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brignole-Baudouin F,, Desbenoit N,, Hamm G,, et al. A new safety concern for glaucoma treatment demonstrated by mass spectrometry imaging of benzalkonium chloride distribution in the eye, an experimental study in rabbits. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e50180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Desbenoit N,, Schmitz-Afonso I,, Baudouin C,, et al. Localisation and quantification of benzalkonium chloride in eye tissue by TOF-SIMS imaging and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013; 405: 4039–4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stevens AM,, Kestelyn PA,, De Bacquer D,, Kestelyn PG. Benzalkonium chloride induces anterior chamber inflammation in previously untreated patients with ocular hypertension as measured by flare meter: a randomized clinical trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012; 90: e221–e224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collin HB,, Carroll N. Ultrastructural changes to the corneal endothelium due to benzalkonium chloride. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1986; 64: 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Debbasch C,, Pisella PJ,, De Saint Jean M,, Rat P,, Warnet JM,, Baudouin C. Mitochondrial activity and glutathione injury in apoptosis induced by unpreserved and preserved beta-blockers on Chang conjunctival cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 2525–2533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buron N,, Guery L,, Creuzot-Garcher C,, et al. Trefoil factor TFF1-induced protection of conjunctival cells from apoptosis at premitochondrial and postmitochondrial levels. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 3790–3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clouzeau C,, Godefroy D,, Riancho L,, Rostene W,, Baudouin C,, Brignole-Baudouin F. Hyperosmolarity potentiates toxic effects of benzalkonium chloride on conjunctival epithelial cells in vitro. Mol Vis. 2012; 18: 851–863. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Y-W-Man P,, Turnbull DM,, Chinnery PF. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. J Med Genet. 2002; 39: 162–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baracca A,, Solaini G,, Sgarbi G,, et al. Severe impairment of complex I-driven adenosine triphosphate synthesis in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy cybrids. Arch Neurol. 2005; 62: 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howell N. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy: respiratory chain dysfunction and degeneration of the optic nerve. Vision Res. 1998; 38: 1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirches E. LHON: mitochondrial mutations and more. Curr Genomics. 2011; 12: 44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Datta S,, Tomilov A,, Cortopassi G. Identification of small molecules that improve ATP synthesis defects conferred by Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy mutations. Mitochondrion. 2016; 30: 177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Bergen NJ,, Crowston JG,, Craig JE,, et al. Measurement of systemic mitochondrial function in advanced primary open-angle glaucoma and Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0140919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leske MC,, Heijl A,, Hyman L,, Bengtsson B,, Dong L,, Yang Z. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114: 1965–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heijl A,, Leske MC,, Bengtsson B,, Hyman L,, Bengtsson B,, Hussein M. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002; 120: 1268–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coleman AL. Glaucoma. Lancet. 1999; 354: 1803–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee S,, Sheck L,, Crowston JG,, et al. Impaired complex-I-linked respiration and ATP synthesis in primary open-angle glaucoma patient lymphoblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 2431–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. He Y,, Leung KW,, Zhang YH,, et al. Mitochondrial complex I defect induces ROS release and degeneration in trabecular meshwork cells of POAG patients: protection by antioxidants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 1447–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lascaratos G,, Chau KY,, Zhu H,, et al. Resistance to the most common optic neuropathy is associated with systemic mitochondrial efficiency. Neurobiol Dis. 2015; 82: 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vranka JA,, Kelley MJ,, Acott TS,, Keller KE. Extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork: intraocular pressure regulation and dysregulation in glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2015; 133: 112–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alvarado JA,, Yeh RF,, Franse-Carman L,, Marcellino G,, Brownstein MJ. Interactions between endothelia of the trabecular meshwork and of Schlemm's canal: a new insight into the regulation of aqueous outflow in the eye. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2005; 103: 148–162; discussion 162–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sahdeo S,, Tomilov A,, Komachi K,, et al. High-throughput screening of FDA-approved drugs using oxygen biosensor plates reveals secondary mitofunctional effects. Mitochondrion. 2014; 17: 116–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pang IH,, Shade DL,, Clark AF,, Steely HT,, DeSantis L. Preliminary characterization of a transformed cell strain derived from human trabecular meshwork. Curr Eye Res. 1994; 13: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Danielson SR,, Wong A,, Carelli V,, Martinuzzi A,, Schapira AH,, Cortopassi GA. Cells bearing mutations causing Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy are sensitized to Fas-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277: 5810–5815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tomilov A,, Bettaieb A,, Kim K,, et al. Shc depletion stimulates brown fat activity in vivo and in vitro. Aging Cell. 2014; 13: 1049–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu Y,, Veena CK,, Morgan JB,, et al. Methylalpinumisoflavone inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) activation by simultaneously targeting multiple pathways. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284: 5859–5868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skehan P,, Storeng R,, Scudiero D,, et al. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990; 82: 1107–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marroquin LD,, Hynes J,, Dykens JA,, Jamieson JD,, Will Y. Circumventing the Crabtree effect: replacing media glucose with galactose increases susceptibility of HepG2 cells to mitochondrial toxicants. Toxicol Sci. 2007; 97: 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dykens JA,, Jamieson JD,, Marroquin LD,, et al. In vitro assessment of mitochondrial dysfunction and cytotoxicity of nefazodone, trazodone, and buspirone. Toxicol Sci. 2008; 103: 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wallace KB,, Starkov AA. Mitochondrial targets of drug toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000; 40: 353–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tektas OY,, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Structural changes of the trabecular meshwork in different kinds of glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2009; 88: 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. He Y,, Ge J,, Tombran-Tink J. Mitochondrial defects and dysfunction in calcium regulation in glaucomatous trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 4912–4922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Izzotti A,, Longobardi M,, Cartiglia C,, Sacca SC. Mitochondrial damage in the trabecular meshwork occurs only in primary open-angle glaucoma and in pseudoexfoliative glaucoma. PLoS One. 2011; 6: e14567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]