Abstract

Each year millions of young children undergo procedures requiring sedation or general anesthesia. An increasing proportion of these anesthetics are provided to optimize diagnostic imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging. Concern regarding the neurotoxicity of sedatives and anesthetics has prompted the US Food and Drug Administration to change labelling of anesthetics and sedative agents warning against repeated or prolonged exposure in young children. This review aims to summarize the risk of anesthesia in children with an emphasis on anesthetic-related neurotoxicity, acknowledge the value of pediatric neuroimaging, and address this call for conversation.

Keywords: anesthesia, anesthetic, children, diagnostic imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, neurodevelopment, neuroimaging, neurotoxicity, sedation

There is heightened concern surrounding the safety of sedation and anesthetic medications in young children. Animal studies consistently report brain injury and behavior changes in animals exposed to sedatives during critical periods of brain development. Likewise, evolving yet inconsistent human studies suggest an association between anesthetic exposure and cognitive delay. This theoretical risk of anesthetic-related neurotoxicity must be placed in the context of the known risks of procedural sedation and perceived benefits of the indicated procedure. SmartTots, a Public-Private Partnership between the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the International Anesthesia Research Society, recently released a revised consensus statement recommending a conversation “among all members of the care team as well as the family” regarding timing of procedures or tests which require anesthesia while affirming that anesthetic drugs are a necessary part of diagnostic studies in infants and toddlers that cannot be delayed [1–3]. This statement is endorsed by 19 leading United States and global health organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia, and recommends that “concerns regarding the unknown risk of anesthetic exposure to [the] child’s brain development must be weighed against the potential harm associated with cancelling or delaying a needed procedure” [3]. More recently, the FDA announced the addition ofa warning to be added to labels of general anesthetic and sedation medications indicating that “repeated and lengthy (>3 hours) use of general anesthetic and sedation drugs during surgeries or procedures in children younger than 3 years or in pregnant women in the third trimester may affect the child’s developing brain” [4]. Neuroimaging is an increasingly common indication for sedation or general anesthesia in young children. Since child neurologists may be unfamiliar with the risks of general anesthesia/sedation and anesthesiologists may be unfamiliar with the clinical indications for neuroimaging, the authors aim to unite both specialties and review the risks of anesthesia and sedation in young children with an emphasis on anesthetic-related neurotoxicity, discuss the value of pediatric neuroimaging, and impart a framework from which this conversation might occur.

Risk of Anesthesia in Children

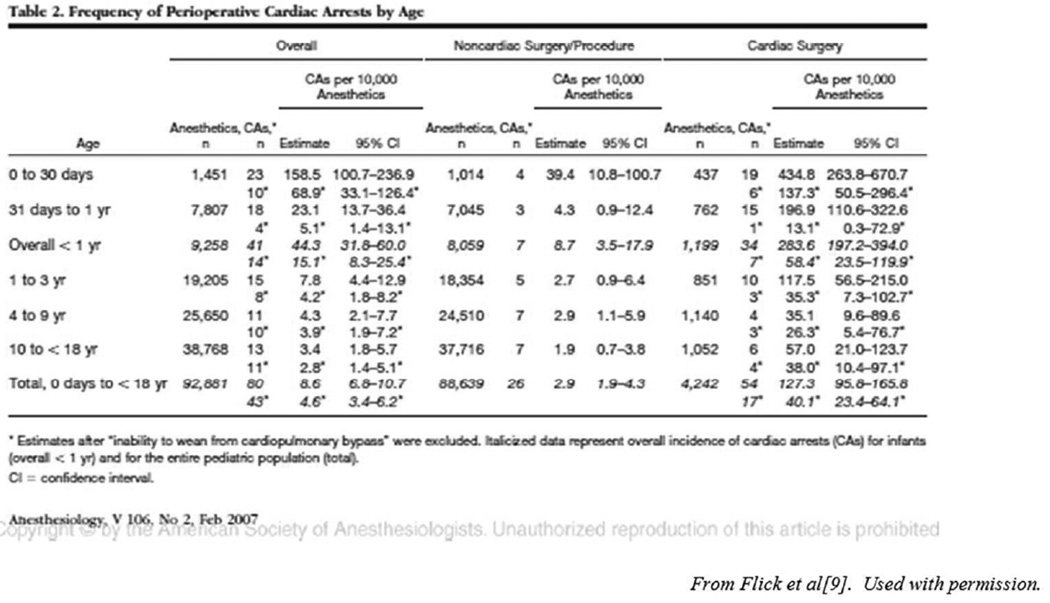

The safety of pediatric anesthesia has increased over the past several decades with improved monitoring, equipment, medications, and growing subspecialization and regionalization of pediatric care [5, 6]. Despite these advances, anesthetic-related complications occur more often in children compared to adults [7, 8]. Specifically, infants and children less than 3 years of age and children with comorbid conditions are at the highest risk of morbidity associated with general anesthesia [7, 9, 10]. Reasons for this increased anesthetic risk in young children are multifactorial and include limited cardiopulmonary reserve, multiorgan immaturity, altered total body water composition relative to adults, limited pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data on commonly used medications in children, altered sensitivity to drugs relative to older children, temperature lability, care team experience, and monitoring difficulties, especially in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suites secondary to magnetic interference [11].

Anesthesia-related Neurotoxicity

Animal research reporting permanent neurocognitive impairment has created new concerns regarding the safety of anesthetics and sedatives in young children, generating significant attention and concern among health care providers and parents alike. Preclinical studies of anesthetic neurotoxicity originate from mechanistic studies of fetal alcohol syndrome, a well-known, well-characterized, permanent neurotoxidrome [12–16]. A sentinel study found that exposure of developing rodents to ethanol, a known N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonist, during periods of synaptogenesis caused widespread apoptotic neurodegeneration of the rat forebrain [14]. Since nearly all anesthetic and sedative agents are believed to modulate either NMDA- or GABA-mediated signaling, it was hypothesized that exposure of developing animals to common sedatives modulating these receptors might induce a similar degree of neuronal cell death as that reported for ethanol. Over the last 15 years, there have been innumerable reports demonstrating widespread neurodegeneration in response to essentially all known sedatives and anesthetics with overt concern for long-term developmental impairment. These histologic changes have reported developmental significance as the combination of midazolam, nitrous oxide, and isoflorane induced both neuroapoptosis and persistent memory and learning impairments in infant rats [17]. These data has also been replicated in nonhuman primates, demonstrating both neuroapoptosis and persistent deficits in motivation, color and position discrimination tasks, response speed, and task performance accuracy after a single exposure to 24 hours of ketamine during the first week of life. Of note, these animals are presently over 5 years old and continue to demonstrate decreased task performance relative to controls [18]. A recent systematic review of preclinical anesthetic neurotoxicity studies in MEDLINE revealed close to 1,000 articles published since 2004 related to this subject [13]. Despite heterogeneous methodologies impairing direct comparison, preclinical studies suggest a window of vulnerability for anesthesia-induced neuronal cell death, the presence of a dose-dependent neurotoxic response to anesthetics, and amplified toxicity with multiple exposures to the same anesthetic agent [13, 19].

Replication of these animal studies in humans is not ethically possible, and direct translation of these results to clinical medicine is impossible. Thus, retrospective epidemiologic studies and emerging prospective clinical trials have been conducted or are currently underway to better understand the relevance of preclinical studies to young children, if any [20–26]. Despite known limitations of retrospective studies, heterogeneity in methodology, degree of confounding, and differing outcome measurements, a cumulative analysis suggests an association between adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes and exposure of anesthesia at an early age [12]. The strength of this association is weak, however, with the majority of studies reporting hazard ratios less than 2 [27, 28].

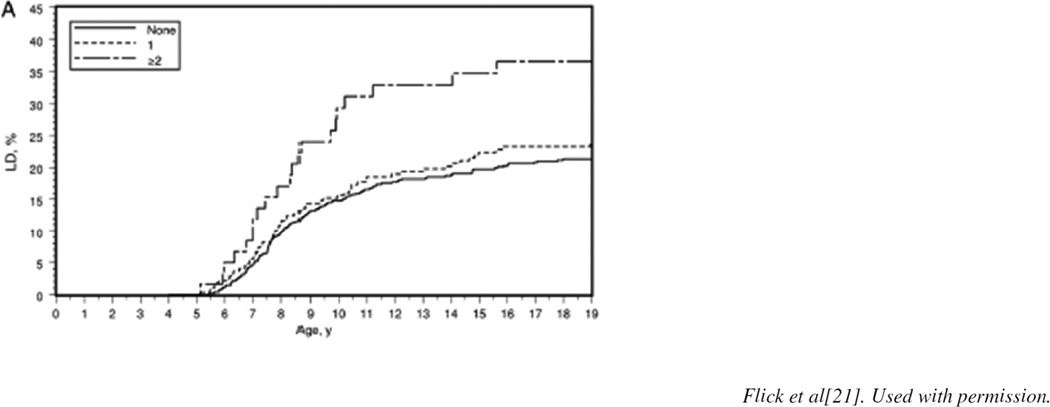

Despite their limitations, extant studies suggest that single brief anesthetic exposures do not appear to produce a measurable effect whereas repeated exposures consistently demonstrate associations between exposure and subsequent deficits in learning and behavior (Figure 1)[21]. The potential ramifications of the associations thus described emphasize the importance of the ongoing prospective studies to parents, providers, and regulators. The General Anesthesia Compared to Spinal Anesthesia (GAS) trial, an international multisite randomized controlled trial, was designed to study cognitive outcomes at 2 and 5 years of age in over 700 neonates randomized to either general or spinal anesthesia for hernia surgery [26]. Recent analysis of the secondary outcome (neurodevelopment at 2 years of age) found no evidence of adverse neurodevelopment at 2 years of age in infants receiving less than 1 hour of general anesthesia with sevoflorane compared with awake-regional anesthesia [26]. Similarly, the multicenter Pediatric Anesthesia NeuroDevelopment Assessment (PANDA) study examined the effect of a single brief anesthetic on performance in a sibling cohort discordant for exposure to general anesthesia for inguinal hernia repair. Like the GAS study, the PANDA study examined the effect of a single brief exposure and was also negative [29–31]. In this multisite sibling-matched cohort study, healthy children exposed to a single anesthetic before 36 months of age compared to healthy siblings without anesthesia exposure had no difference in IQ scores in later childhood [31]. The Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) study is a collaboration between Mayo Clinic and the National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR). [30] It is a population-based propensity-matched study comparing performance on neuropsychologic testing (NCTR-Operant Test Battery) of children who were exposed to anesthesia prior to 3 years of age with unexposed children. The Operant Test Battery has been used to study anesthetic-related neurotoxicity in nonhuman primates and offers a direct comparison of effects of anesthetic exposure in children and nonhuman primates performing identical behavioral tasks [30]. Human studies examining anesthesia and surgery associated neurodevelopmental outcomes are summarized in Table 1. Until further studies clarify the effect of anesthesia on neurodevelopmental outcome in young children, the risks remain unknown and health care teams are left to weigh the known risks (eg, aspiration, bronchospasm, laryngospasm, cardiac arrest) and unknown risks (eg, anesthetic-related neurotoxicity) of anesthesia with the perceived benefits of diagnostic procedures [3].

Figure 1.

Estimated cumulative percentage of children with learning disabilities (LD) for those with 0, 1, and multiple exposures to anesthesia before the age of 2 years[21].

Table 1.

Summary of Human Studies Examining Anesthesia and Surgery Associated Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

| Design (study period) |

Sample size | Operations | Age at exposure |

Anesthetic agents and duration |

Confounder adjustment |

Outcome assessment |

Follow-up | Neurodevelopmental outcomes |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Neurodevelopmental Outcome | |||||||||

| DiMaggio et al. 2009[32] |

Birth cohort (1999–2001) |

383 exposed, 5050 unexposed |

Inguinal hernia repair (ICD-9 code) |

≤3 yrs | No | Age, sex, race, birth complications |

4 yrs | Behavioral/Develop- mental ICD-9 codes |

Increased incidence of behavioral/developmental diagnoses associated with hernia repair after controlling for confounders |

| Wilder et al. 2009[20] |

Birth cohort (1976–1982) |

449 singly exposed, 144 multiply exposed, and 4,674 unexposed |

Varied | <4 yrs | Yes | Sex, birth weight, gestational age |

≤19 yrs | LD cases identified based on research criteria from review of school and medical records |

Two-fold increase in risk of LD frequency among multiple exposed children after adjustment |

| Bartels et al. 2009[33] |

Twin-pair cohort (1986–1995) |

154 exposed, 648 unexposed |

Varied | <3 yrs and <12 yrs |

No | Sex | 12 yrs | Academic achievement and CTRS |

Lower achievement scores in concordant twin pairs-exposed compared to concordant twin pairs-unexposed. No difference between twins within discordant twin pairs |

| DiMaggio et al. 2011[23] |

Retrospective cohort (1999–2005) |

304 exposed, 10,146 unexposed |

Varied | <3 yrs | No | Sex, birth weight, birth-related complication, and clustering for sibling status; Sibling-matched analysis |

≤4 yrs | Developmental and behavioral diagnoses (ICD-9 codes) |

Increased risk of developmental and behavioral disorders among multiply exposed children. No difference in developmental or behavioral diagnoses among sibling pairs with discordant exposure status |

| Ing et al. 2012[25] |

Birth cohort (1989–1992) |

321 exposed, 2287 unexposed |

Varied | <3 yrs | No | Sex, low birth weight, race, income, maternal education level |

≤10 yrs | Neuropsychological test batteries |

Impaired performance in language (CELF test) and cognition (CPM test), but not behavior or motor functions |

| Sprung et al. 2012[22] |

Birth cohort (1976–1982) |

286 singly exposed, 64 multiple exposed, and 5,007 unexposed children |

Varied | <2 yrs | Yes | Adjusted for sex, birth weight, and gestational age; stratified for propensity of receiving general anesthesia |

≤19 yrs | ADHD cases identified based on research criteria from review of school and medical records |

Two-fold increase in risk of ADHD frequency among multiply exposed children after adjustment |

| Flick et al. 2011[21] |

Matched cohort (1976–1982) |

286 single exposed, 64 multiple exposed, and 700 unexposed children |

Varied | <2 yrs | Yes | Adjusted for sex, birth weight, and gestational age; Adjusted for propensity of receiving general anesthesia |

≤19 yrs | LD cases identified based on research criteria, need for IEPs, and performance in group achievement tests |

Two-fold increase in risk of LD frequency among multiply exposed children after adjustment. Increased need for IEP for speech language impairment |

| Block et al. 2012[34] |

Cohort (1990–2008) |

287 exposed | Inguinal hernia repair, orchidopexy, pyloromyotomy, and circumcision |

<1 yr | Yes | CNS problems/risk factors, birth weight |

7-10 yrs | Academic achievement tests |

Association between lower test scores and longer duration of anesthesia and surgery. No difference in achievement test scores among children without CNS risk factors |

| Ing et al. 2014[35] |

Birth cohort (1989–1992) |

112 exposed, 669 unexposed |

Varied | <3 yrs | No | Sex, low birth weight, race, income, and maternal education |

≤10 yrs | Neuropsychological tests, ICD-9 codes, group-administered achievement tests |

Compared with unexposed peers, exposed children had an increased risk of deficit in neuropsychological language assessments (CELF) and ICD- 9 coded language and cognitive disorders, but not academic achievement scores |

| Stratmann et al. 2014[36] |

Matched cohort (2011–2013) |

28 exposed, 28 unexposed |

Varied | <2 yrs | Yes | Age and sex matched; exclusion of intraoperative confounding factors |

6-11 yrs | Test of recognition memory, IQ, and CBCL |

Impairment in recollection memory in exposed children, but no difference in familiarity, IQ, or CBCL |

| Backeljauw et al. 2015[37] |

Matched cohort (Recent) |

53 exposed, 53 unexposed |

Varied | <4 yrs | Yes | Age, sex, handedness, SES |

5-18 yrs | OWLS and WAIS or WISC |

Lower score in listening comprehension and performance IQ among exposed children |

| No Difference in Neurodevelopmental Outcome | |||||||||

| Hansen et al. 2011[24] |

Birth cohort (1986–1990) |

2,689 exposed, 14,575 unexposed |

Inguinal hernia repair | <1 yr | No | Sex, birth weight, parental age and education |

15-16 yrs | Ninth grade test average and average teacher rating |

No significant difference in test performance. |

| Hansen et al. 2013[38] |

Birth cohort (1986–1990) |

779 exposed, 14,665 unexposed |

Pyloromyotomy | <3 mo | No | Sex, birth weight, parental age and education |

15-16 yrs | Ninth grade test average and average teacher rating |

No significant difference in test performance. |

| Davidson et al. 2016[26] |

Randomized controlled trial (2007–2013) |

238 RA, 294 GA |

Inguinal herniorrhaphy | Up to 60 weeks post- menstrual age |

Yes | No (randomized trial) |

2 yrs | Neuropsychological test batteries (Bayley- III and MacArthur- Bates scores) |

No difference in Bayley-III and MacArthur-Bates scores at 2 yrs |

| Sun et al. 2016[31] |

Sibling matched cohort |

105 sibling pairs |

Inguinal herniorrhaphy | <3 yrs | Yes | Sibling matched, age difference within 3 yrs |

8-15 yrs | Neuropsychological test batteries |

No statistically significant differences in mean scores between sibling pairs in IQ, memory/learning, motor/processing speed, visuospatial function, attention, executive function, language, or behavior. |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CBCL, Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist; CELF, clinical evaluation of language fundamentals; CNS, central nervous system; CPM, Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices; CTRS, Connor Teacher Rating Scale; GA, general anesthesia; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; IEP, individualized education program; IQ, intelligence quotient; LD, learning disabilities; OWLS, Oral and Written Language Scales; RA, regional anesthesia; SES, socioeconomic status; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; WISC, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children.

Sedation-related Neurotoxicity

As alluded to above, it is important to note that the label anesthetic neurotoxicity may be a misnomer because the implicated medications are widely used outside of the conduct of a general anesthetic. Equally important, subanesthetic doses of these sedatives demonstrate neurodegeneration in laboratory animals [39]. The same medications used during the course of a general anesthetic are commonly used for sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures outside of the operating room. Exposure to these medications, particularly in the intensive care unit, may be of particular importance as doses are commonly high and exposure time prolonged [40–45].

Value of Neuroimaging in Children

Neuroimaging in infants and young children often requires sedation or general anesthesia for both patient comfort and accurate interpretation of study results. The value or diagnostic yield of imaging in children is a complicated discussion reflecting the heterogeneity of clinical indications. Most studies assessing imaging yield describe how often pertinent positive findings are identified that change acute management; however, the ability of imaging to rule out pathology is often equally important and its value understated. Diagnostic yield varies between organ systems, diagnoses within the same system, and even within the same general diagnosis. The pediatric neuroimaging guidelines set by the American Academy of Neurology depend on whether a child is being evaluated for microcephaly, status epilepticus, global developmental delay, or cerebral palsy [46]. A child presenting with classic clinical and electroencephalographic features of a genetic, generalized epilepsy and a normal examination does not necessarily need neuroimaging; whereas, neuroimaging is recommended in a child with focal epilepsy and an abnormal examination. The strength of evidence for neuroimaging varies by diagnosis. For instance, a substantial number of children with new-onset seizure and status epilepticus will have urgent or emergent intracranial pathology identified on neuroimaging while the vast majority of children with mild traumatic brain injury do not require neuroimaging [47, 48].

The risk-benefit analysis regarding imaging decision-making is complex. This includes decisions on the optimal imaging modality and optimal timing to obtain or repeat imaging. For example, an infant with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy may benefit more from a brain MRI compared to computed tomography (CT) study, but the imaging timing may depend on several factors, including concomitant therapeutic hypothermia [49]. While CT studies rarely require anesthesia in children, the diagnostic yield of a head CT can be limited and the risk associated with ionizing radiation in children is a major concern [50–52]. A retrospective study of pediatric CT scan use in the United Kingdom reported a dose-response relationship between risk of leukemia and brain cancer and ionizing radiation exposure – a dose-response relationship compatible with that observed in Japanese atomic bomb survivors [50, 53]. Re-analysis of the cohort excluding participants with cancer-predisposing conditions continued to show increased cancer risk after low-dose radiation exposure from CT scans in young children [53]. While the Joint Commission and the American College of Radiology promote the reduction of CT use in children, the long term impact of recent CT dose-reduction strategies on the risk of cancer in children is unknown [54]. Even though MRI does not expose children to radiation, risk exists apart from anesthesia as there is a strong association between gadolinium-based contrast agents used in MRI and nephrogenic system fibrosis (NSF) in patients with renal impairment and pro-inflammatory conditions [55]. While this multisystem disease is rare with ten biopsy-proven cases reported in children, it can be fatal [55].

Once a decision is made to pursue imaging, it is worth noting that options exist to help minimize risk. MRI-compatible neonatal incubators can help minimize transport-associated risk [56], and neonates can often tolerate a MRI while sleeping without the need for anesthesia. The frequency of unsedated MRIs in neonates is increasing, especially as MRI acquisition techniques advance to diminish movement artefact. [57] Ultra-fast techniques are available for some diagnostic studies, and evidence supports the use of ultra-fast MRI for the assessment of ventricular size in children with shunt-treated hydrocephalus. [57, 58] Finally, consideration may be given to combining multiple studies and procedures requiring anesthesia in children to limit exposure; however, an individual risk-benefit analysis in the context of the present healthcare practice may not support this as risk of transport and additional anesthesia exposure between studies may outweigh the perceived benefit.

Call for Conversation

When neuroimaging is necessary in young children, the prescribing physician is the ideal person to initiate a conversation with the family and care team regarding timing and outcome-changing potential of the requested study. Since most MRI studies in young children require sedation or general anesthesia, and sedation is no safer than general anesthesia, pediatric neurologists should be familiar with the risks in order to best navigate this discussion and address parental concerns, especially since parents are the ultimate patient advocate and consumer of mainstream media and are increasingly questioning the risk.

Since families differ in regard to the information desired, it is the authors’ practice to take an individualized approach by discussing risks of anesthesia in general terms and inviting parents and older children to ask for more specific information. Since the risk of anesthetic-related neurotoxicity is unknown and theoretical, no mention of this topic is made unless requested. Consistent with our practice, a recent survey of current pediatric anesthesia practices at United States teaching institutions found that over 90% of pediatric anesthesiologists discuss the issue of neurotoxicity “only if asked” [59]. When parents and older children do ask, the authors welcome the conversation and provide reassurance that a single, short exposure of general anesthesia does not appear to increase the risk of an adverse neurodevelopmental outcome [26, 31]. In addition, we share with inquisitive parents the low rate of harm associated with anesthesia and lack of compelling evidence to date of a causal relationship between anesthetic exposure and developmental delay. Since anesthesiologists often meet their patients on the day of the scheduled study when parents are anxious and children are fasting, child neurologists can help their colleagues in anesthesiology by preemptively addressing parental questions and affirming the importance of the recommended study to families, emphasizing how the test result will directly alter the child’s treatment plan and health outcome. Furthermore, pediatric anesthesiologists would willingly assist their colleagues in pediatric neurology with this discussion and welcome preprocedural consultation as questions and concerns arise.

Until further research clarifies the impact of anesthetic and sedative medications on neurodevelopment or until neuroimaging technology advances beyond the need for general anesthesia for these studies in young children, pediatric neurologists and anesthesiologists should work together engaging in conversation to provide the best care, minimizing risk and maximizing benefit for the health of all children [60].

Table 2.

Frequency of Perioperative Cardiac Arrests by Age

Estimates after “Inability to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass” were excluded. Italicized data represent overall incidence of cardiac arrests (CAs) for infants (overall < 1 yr) and for the entire pediatric population (total).

CI = confidence interval.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by grant HD071907 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Dr. Flick previously served as Chair of the Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee, has conducted research under contract for the US Food and Drug Administration, is Co-Primary Investigator on a federally funded grant (United States National Institute of Child Health and Development), and serves as an advisor to SmartTots.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The other authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.SmartTots Consensus Statement on the Use of Anesthetics and Sedatives in Children December 2012. Available from: http://www.asdahq.org/sites/default/files/Smart%20Tots%20Consensus%20Statement%202012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.SmartTots Consensus Statement Supplement 11/2015. Available from: http://smarttots.org/consensus-statement-supplement/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.SmartTots Consensus Statement on the Use of Anesthetics and Sedative Drugs in Infants and Toddlers October 2015. Available from: http://smarttots.org/about/consensus-statement/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medscape. FDA Warns on Anesthetic, Sedative Use in Pregnant Women, Kids. [12/14/2016]; Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/873310_print. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee C, Mawson L. Complications in paediatric anaesthesia. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2006;19(3):262–267. doi: 10.1097/01.aco.0000192787.93386.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morray JP. Cardiac arrest in anesthetized children: recent advances and challenges for the future. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2011;21(7):722–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morray JP, et al. A comparison of pediatric and adult anesthesia closed malpractice claims. Anesthesiology. 1993;78(3):461–467. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flick RP, et al. Perioperative cardiac arrests in children between 1988 and 2005 at a tertiary referral center: a study of 92,881 patients. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(2):226–237. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200702000-00009. quiz 413–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paterson N, Waterhouse P. Risk in pediatric anesthesia. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2011;21(8):848–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez N, et al. An update on pediatric anesthesia liability: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2007;104(1):147–153. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000246813.04771.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss M, Hansen TG, Engelhardt T. Ensuring safe anaesthesia for neonates, infants and young children: what really matters. Archives of disease in childhood. 2016 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders RD, et al. Impact of anaesthetics and surgery on neurodevelopment: an update. British journal of anaesthesia. 2013;110(Suppl 1):i53–i72. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Disma N, et al. A systematic review of methodology applied during preclinical anesthetic neurotoxicity studies: important issues and lessons relevant to the design of future clinical research. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2016;26(1):6–36. doi: 10.1111/pan.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikonomidou C, et al. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science. 2000;287(5455):1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joksovic PM, et al. Early Exposure to General Anesthesia with Isoflurane Downregulates Inhibitory Synaptic Neurotransmission in the Rat Thalamus. Molecular neurobiology. 2015;52(2):952–958. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9247-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsang TW, et al. Prenatal Alcohol Exposure, FASD, and Child Behavior: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23(3):876–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paule MG, et al. Ketamine anesthesia during the first week of life can cause long-lasting cognitive deficits in rhesus monkeys. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011;33(2):220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loepke AW, Vutskits L. What lessons for clinical practice can be learned from systematic reviews of animal studies? The case of anesthetic neurotoxicity. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2016;26(1):4–5. doi: 10.1111/pan.12826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilder RT, et al. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(4):796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flick RP, et al. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes after early exposure to anesthesia and surgery. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1053–e1061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sprung J, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder after early exposure to procedures requiring general anesthesia. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2012;87(2):120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiMaggio C, Sun LS, Li G. Early childhood exposure to anesthesia and risk of developmental and behavioral disorders in a sibling birth cohort. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2011;113(5):1143–1151. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182147f42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen TG, et al. Academic performance in adolescence after inguinal hernia repair in infancy: a nationwide cohort study. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(5):1076–1085. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820e77a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ing C, et al. Long-term differences in language and cognitive function after childhood exposure to anesthesia. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e476–e485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidson AJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age after general anaesthesia and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10015):239–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00608-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flick RP, Warner DO. A users' guide to interpreting observational studies of pediatric anesthetic neurotoxicity: the lessons of Sir Bradford Hill. Anesthesiology. 2012;117(3):459–462. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31826446a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemergut ME, Aganga D, Flick RP. Anesthetic neurotoxicity: what to tell the parents? Paediatric anaesthesia. 2014;24(1):120–126. doi: 10.1111/pan.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun LS, et al. Feasibility and pilot study of the Pediatric Anesthesia NeuroDevelopment Assessment (PANDA) project. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2012;24(4):382–388. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31826a0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gleich SJ, et al. Neurodevelopment of children exposed to anesthesia: design of the Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) study. Contemporary clinical trials. 2015;41:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun LS, et al. Association Between a Single General Anesthesia Exposure Before Age 36 Months and Neurocognitive Outcomes in Later Childhood. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2312–2320. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiMaggio C, et al. A retrospective cohort study of the association of anesthesia and hernia repair surgery with behavioral and developmental disorders in young children. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2009;21(4):286–291. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181a71f11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartels M, Althoff RR, Boomsma DI. Anesthesia and cognitive performance in children: no evidence for a causal relationship. Twin research and human genetics : the official journal of the International Society for Twin Studies. 2009;12(3):246–253. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Block RI, et al. Are anesthesia and surgery during infancy associated with altered academic performance during childhood? Anesthesiology. 2012;117(3):494–503. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182644684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ing CH, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after initial childhood anesthetic exposure between ages 3 and 10 years. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2014;26(4):377–386. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stratmann G, et al. Effect of general anesthesia in infancy on long-term recognition memory in humans and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(10):2275–2287. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Backeljauw PF, et al. Proceedings from the Turner Resource Network symposium: the crossroads of health care research and health care delivery. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2015;167A(9):1962–1971. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen TG, et al. Educational outcome in adolescence following pyloric stenosis repair before 3 months of age: a nationwide cohort study. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2013;23(10):883–890. doi: 10.1111/pan.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cattano D, et al. Subanesthetic doses of propofol induce neuroapoptosis in the infant mouse brain. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2008;106(6):1712–1714. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172ba0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monteleone M, et al. Anesthesia in children: perspectives from nonsurgical pediatric specialists. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2014;26(4):396–398. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tasker RC, Vitali SH. Continuous infusion, general anesthesia and other intensive care treatment for uncontrolled status epilepticus. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2014;26(6):682–689. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutter R, et al. Anesthetic drugs in status epilepticus: risk or rescue? A 6-year cohort study. Neurology. 2014;82(8):656–664. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim SJ, Lee DY, Kim JS. Neurologic outcomes of pediatric epileptic patients with pentobarbital coma. Pediatric neurology. 2001;25(3):217–220. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(01)00311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Ikonomidou C. Antiepileptic drugs and apoptosis in the developing brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;993:103–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07517.x. discussion 123–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duerden EG, et al. Midazolam dose correlates with abnormal hippocampal growth and neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants. Annals of neurology. 2016;79(4):548–559. doi: 10.1002/ana.24601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Academy of Neurology. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Available from: https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/Home/ByTopic?topicId=14. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lyons TW, et al. Yield of emergent neuroimaging in children with new-onset seizure and status epilepticus. Seizure. 2016;35:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nigrovic LE, et al. Prevalence of clinically important traumatic brain injuries in children with minor blunt head trauma and isolated severe injury mechanisms. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):356–361. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charon V, et al. Comparison of early and late MRI in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy using three assessment methods. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45(13):1988–2000. doi: 10.1007/s00247-015-3419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearce MS, et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380(9840):499–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathews JD, et al. Cancer risk in 680,000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: data linkage study of 11 million Australians. BMJ. 2013;346:f2360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brody AS, et al. Radiation risk to children from computed tomography. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):677–682. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berrington de Gonzalez A, et al. Relationship between paediatric CT scans and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: assessment of the impact of underlying conditions. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(4):388–394. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson KT, et al. Don't forget the dose: Improving computed tomography dosing for pediatric appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51(12):1944–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weller A, Barber JL, Olsen OE. Gadolinium and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: an update. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(10):1927–1937. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paley MN, et al. An MR-compatible neonatal incubator. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1015):952–958. doi: 10.1259/bjr/30017508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woodfield J, Kealey S. Magnetic resonance imaging acquisition techniques intended to decrease movement artefact in paediatric brain imaging: a systematic review. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45(9):1271–1281. doi: 10.1007/s00247-015-3333-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rozovsky K, Ventureyra EC, Miller E. Fast-brain MRI in children is quick, without sedation, and radiation-free, but beware of limitations. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(3):400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ward CG, et al. Neurotoxicity, general anesthesia in young children, and a survey of current pediatric anesthesia practice at US teaching institutions. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2016;26(1):60–65. doi: 10.1111/pan.12814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.American Academy of Pediatrics. Available from: https://www.aap.org/ [Google Scholar]