Abstract

This study examined how social support seeking and rumination interacted to predict depression and anxiety symptoms six months later in early adolescents (N = 118; 11 – 14 yrs at baseline). We expected social support seeking would be more helpful for adolescents engaging in low rather than high levels of rumination. Adolescents self-reported on all measures at baseline, and on depression and anxiety symptoms six months later. Social support seeking predicted fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety at low rumination levels, but lost its adaptive effects as rumination increased. For depression symptoms, social support seeking led to more symptoms at high rumination levels. Results were stronger for emotion-focused than problem-focused support seeking, and for depression compared to anxiety symptoms. These findings suggest that cognitive risk factors like rumination may explain some inconsistencies in previous social support literature, and highlight the importance of a nuanced approach to studying social support seeking.

Keywords: Social support, coping, depression, anxiety, risk/resilience

Adolescence has been identified as a critical developmental period for depression symptoms and disorders. Although clinical depression is relatively uncommon in children, depression rates increase in adolescence such that 15–20% of youth will experience an episode of clinical depression before the end of high school (e.g., Kessler, Avenevoli, & Merikangas, 2001). Further, up to 50% of adolescents will experience high subclinical levels of depression (Kessler et al., 2001) which have been shown to be associated with similar impairments as clinical levels of depression (Gotlieb, Lewinsohn, & Seely, 1995). Similarly, anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent mental health disorders in young people, with a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorder in children and adolescents of approximately 15–20% (Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2009). There is also strong and consistent evidence that anxiety and depression disorders and symptoms frequently co-occur both concurrently and sequentially (e.g., Chaplin, Gillham, & Seligman, 2009; Garber & Weersing, 2010) and that the development of depression or anxiety symptoms in young people is predictive of mental health problems into adulthood (e.g., Leadbeater, Thompson, & Gruppuso, 2012). Identifying modifiable risk and protective factors for depression and anxiety symptoms in early adolescence, especially factors that are relevant to symptoms of both depression and anxiety, is essential for developing effective prevention and treatment programs for youth, and for promoting mental health both in adolescence and across the life-span. The current study examines how two factors – rumination and social support seeking – interact in the prediction of anxiety and depression symptoms in early adolescents.

When individuals face challenges or experience difficult emotions in their daily lives, they often seek out close others (e.g., parents, siblings, friends, coworkers) for comfort, support, advice, and help with problem-solving. Both receiving social support and believing that one has access to strong, quality social support have been shown to be protective factors for individuals across the life-span. Positive perceptions of social support predict better psychological and physical health (Thoits, 2011; Uchino, 2006), and have been shown to buffer individuals against the negative effects of stressful events (Hammack, Richards, Luo, Edlynn, & Roy, 2004; Thoits, 2011). High quality friendships predict less depression in youth (e.g., Schmidt & Bagwell, 2007), and a strong parent-child relationship is one of the strongest, most consistent predictors of resilience in young people (Luthar & Zelazo, 2003). Further, seeking out others for support with problems or for support for one’s emotions are common coping strategies that have been studied by multiple coping researchers (e.g., Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, 1996; see Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003 for a review of classifications of coping). Problem-focused support seeking specifically includes efforts such as seeking advice, information, or help with problem solving, whereas emotion-focused support seeking focuses on obtaining support for one’s emotions, and includes efforts such as using others to listen to feelings, or turning to others to provide understanding. Seeking social support, especially problem-focused support, has been conceptualized as a positive strategy for handling problems or negative emotions (e.g., Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989; Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001).

Despite a large body of both theoretical and empirical work indicating that social support is important for well-being in youths and adults, there is growing evidence that turning to others for support may not be uniformly beneficial. For example, research indicates that while social support can buffer individuals against the negative effects of stressors, social support can lose its buffering effects at very high levels of risk (e.g., victimization by community violence, Hammack et al., 2004). Further, some studies examining the links between social support seeking and mental health problems in children and adolescents have either failed to find significant relations (e.g., Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009; Gonzales, Tein, Sandler, & Friedman, 2001; Sandler, Tein, & West, 1994) or found social support seeking to be positively associated with youth mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, and feelings of hopelessness (e.g., Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009; Landis et al., 2007; Sandler et al., 1994). Further, previous work on the efficacy of coping strategies in youth has demonstrated that problem-focused strategies are generally associated with fewer internalizing and externalizing problems, while emotion-focused strategies tended to be associated with more problems (Compas et al., 2001), suggesting that the efficacy of seeking social support may vary according to the specific type of support sought (i.e., problem- vs. emotion-focused).

Recent work in the field of depression has also indicated that support seeking can become a complex and even maladaptive process under certain conditions (e.g., Hankin, Stone, & Wright, 2010; Rose, Carlson, & Waller, 2007). For example, some individuals seek social support through co-rumination, the extensive, passive, and repetitive discussion of problems or negative symptoms with a close other (Rose, 2002). Although co-rumination has been shown to predict increases in perceived positive friendship quality in children and adolescents (Rose, Carlson, & Waller, 2007), co-rumination has also predicted increases in child and adolescent anxiety, depression, and interpersonal stress over time (Hankin, Stone, & Wright, 2010; Rose et al., 2007). Efforts to elicit social support that are characterized by excessive reassurance seeking – the persistent seeking of reassurance that one is loveable and worthy, even if such reassurance has already been provided (Joiner, Metalsky, Katz, & Beach, 1999) – has also been shown to predict increases in symptoms of depression and to contribute to interpersonal difficulties (e.g., Evraire & Dozois, 2011). Such variability in the role of social support seeking in youth mental health suggests that researchers and intervention developers may benefit from adopting a more nuanced view of social support, and should work to identify when and for whom social support seeking is more or less adaptive.

One possible explanation for the variability in findings for social support seeking is that cognitive or behavioral characteristics of individuals may influence how effectively they are able to use social support. One cognitive factor that has been shown to have negative implications both for internalizing problems and for social support is rumination. Rumination is characterized by a passive, repetitive focus on one’s symptoms of depression, as well as the causes and consequences of these symptoms, with no attempts at problem solving or symptom reduction (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). According to Response Styles Theory, how people respond to their symptoms of depression predicts the severity and the duration of depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Specifically, engaging in rumination in response to depressive symptoms is expected to predict more intense and longer lasting depressive symptoms than engaging in other, more adaptive responses such as distraction.

In support of this theory, rumination is associated with a past history of major depressive episodes, predicts future depressive symptoms and depressive episodes, and predicts a greater duration of future episodes of depression in children and early adolescents (e.g., Abela & Hankin, 2011, Abela, Hankin, Sheshko, Fishman, & Stolow, 2012; Abela, Vanderbilt, & Rochon, 2004). Although originally conceptualized as a specific risk factor for depression, there is evidence emerging of relations between rumination and anxiety in children and adolescents (e.g., Lopez, Felton, Driscoll, & Kistner, 2012; Muris, Fokke, & Kwik, 2009). Rumination has been identified as a potential transdiagnostic factor for depression and anxiety in early adolescents (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011), and has been shown to account for the relations between these two conditions (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011).

In addition to contributing to symptoms of depression and anxiety, it is possible rumination may affect how well adolescents engage in social support seeking, potentially altering how beneficial these strategies are for adolescent mental health. Although the interactive effects of rumination and social support seeking on depression and anxiety have not been explored in past work, there is some related evidence to suggest that rumination can affect the amount and quality of social support early adolescents seek and receive. For example, higher levels of rumination are correlated with lower levels of perceived social support (Abela et al., 2004) and cross-sectional evidence suggests that individuals who ruminate are more likely to engage in maladaptive forms of social support seeking such as co-rumination and excessive reassurance seeking (Rose, 2002; Weinstock & Whisman, 2007). These data suggest that adolescents who tend to engage in rumination may have difficulty using their social support network in beneficial ways. When attempting to seek support, advice, and comfort from others, adolescents who frequently ruminate may have difficulty shifting their focus from their negative emotional symptoms and may instead engage in interpersonal behaviors that are maladaptive for their own mental health and their relationships. Despite evidence of the protective effects of social support in the broader literature, social support seeking may be a less adaptive strategy for young people who ruminate frequently than for those who exhibit lower levels of rumination.

The current study thus examined whether rumination moderated the relationship of social support seeking to depression and anxiety symptoms in a sample of early adolescents. We generally expected that social support seeking would be more adaptive for youth who reported low levels of rumination than for youth who reported high levels of rumination. Given that rumination is characterized by a pervasive focus on negative symptoms as well as their causes and consequences, we hypothesized that the attenuating effect of rumination on the benefits of social support seeking for adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms would be stronger for emotion-focused support seeking (e.g., using others to listen to feelings or to provide understanding) than for problem-focused support seeking (e.g., seeking advice, information, or assistance with problem-solving). Although the rumination literature has primarily focused on depression symptoms, recent work has begun to demonstrate that rumination also has implications for anxiety symptoms. Thus, we expected the same pattern of findings for both depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms.

Methods

Recruitment and Study Procedures

Participants were taken from the control group of a larger randomized controlled trial of the Penn Resiliency Program (PRP), a school-based program developed to prevent depression and promote resilience in early adolescents (Gillham et al., 2012). Both the current study and larger trial were approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board. Approximately 8,000 students aged 10–14 attending five middle schools in a suburban metropolitan area in the northeastern United States and their parents were initially contacted about participation by mail. With parental consent and student assent, 1,016 interested students were screened for depressive and anxious symptoms using the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 2001), the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale, second edition (RADS-2, Reynolds, 2002), and the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RMCAS, Reynolds & Richmond, 1985). Slots in the study were first offered to students demonstrating elevated levels of depressive symptoms; remaining slots were offered to other students until recruitment goals were met. Mean screening scores were slightly higher than average but within one standard deviation of the CDI, RADS-2, and RCMAS standardization sample means. In the full PRP sample, 412 adolescents from local middle schools completed baseline assessments. Two thirds of those adolescents were randomly assigned to one of two active intervention conditions; the remaining third (N=129) was assigned to the control group. Participants from the control group for whom all relevant data were available (N = 118) were included in the current analyses. More details about recruitment and the full PRP sample are provided elsewhere (Gillham et al., 2012).

In the larger study, students completed assessments at baseline and every 6 to 12 months thereafter for more than three years. The current study employs data from the control group at baseline and the six-month assessment. Families received $50 for participation per assessment.

Participants

At baseline, participants were students in sixth (49%), seventh (28%), and eighth (23%) grades and between 11 and 14 years of age (M = 12.05, SD = 1.01). Fifty percent of participants were female. Participants’ families reported on race and ethnicity: 78% were Caucasian, 12.7% African American, 4.2% Asian, 0.8% Hispanic, and 4.2% Other. The racial and ethnic make-up of the current sample was representative of the communities from which they were recruited, and did not differ from the screening sample, χ2(6) = 3.94, p = .69. Parental reports showed that 33.9% of mothers and 29.5% of fathers attained an advanced degree or attended some graduate school, 49.1% of mothers and 41.9% of fathers attended or completed college, and 16.9% of mothers and 28.6% of fathers attained a high school education or less. In terms of family marital status, 71.4% were married, 16.2% were divorced or separated, 2.9% were remarried, 6.7% had never been married, and 1% reported “other”. Household incomes ranged from $7,200 to $450,000 annually; median income was $70,500. In terms of depressive symptoms at baseline for the current sample, 19.5% and 22.9% of participants demonstrated “elevated” or “mild” symptoms on the CDI (scores ≥ 20) and RADS2 (scores ≥ 76) respectively; 5.9% and 13.6% demonstrated “clinically elevated” or “moderate” symptoms (CDI ≥ 26; RADS2 ≥ 82).

Measures

Depression symptoms

This study utilized two widely-used measures of depression designed for youth: the CDI (Kovacs, 2001) and the RADS-2 (Reynolds, 2002). Both measures were assessed at baseline and six-month follow-up. At the request of school administrators, items inquiring about suicidal thoughts and self-injurious behavior were removed from the questionnaires. Thus, we used 26 items from the CDI and 29 items from the RADS-2. For each item on the CDI, participants selected which of three sentences best describes them. A sample item is “All bad things are my fault; Many bad things are my fault; Bad things are not usually my fault.” For the RADS-2, participants indicated how much they agreed with each statement on a 4 point likert-type scale. A sample item is, “I feel like nothing I do helps anymore.” Both measures have demonstrated adequate reliability and validity (Kovacs, 2001; Reynolds, 2002). Higher scores correspond to higher levels of depressive symptoms for both the CDI (α = .92) and the RADS-2 (α = .95). To create a single depression symptoms score, we standardized and then averaged scores across the two measures.

Anxiety symptoms

Students completed the RCMAS (Reynolds & Richmond, 1985), a widely-used measure of anxiety in youth, at baseline and six-month follow-up. The RCMAS focuses on several dimensions of anxiety including worry, social anxiety, difficulties with concentration, and physiological symptoms. A sample item is, “I worry about what is going to happen.” The RCMAS has demonstrated adequate internal consistency and correlates well with other measures of anxiety (Reynolds & Richmond, 1985). Higher scores on the RCMAS indicate higher levels of anxiety symptoms (α = .86).

Rumination

Students completed the Short Form of the Ruminative Responses Scale of the Response Style Questionnaire (RRS, Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) at baseline. The short form of the RRS consists of 10 items from the full scale that assess the extent to which respondents ruminate in response to feeling sad or down. These 10 items are those that correlated most strongly with the total scores on the full RRS, and for which at least 15% of the community sample in which it was tested had selected a response other than “never” (Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000); the short form has been shown to correlate very highly with the full RRS scale (i.e., r = .93; Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Sample items include, “I think, ‘Why can’t I handle things better?’” and, “I think about how hard it is to concentrate.” The short form has demonstrated good internal consistency (e.g., Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000) and has been shown to correlate with measures of depression (von Hippel, Vasey, Gonda, & Stern, 2008). Although the Ruminative Response Scale was originally developed for adults, it has also been used with early adolescent samples (e.g., Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Cox, Mezulis, & Hyde, 2010). Coefficient alpha in the current study was .92. Higher scores reflect higher levels of rumination.

Social support seeking

Students completed the Support for Feelings and Support for Actions subscales of the revised Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (CCSC; Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, 1996; Sandler et al., 2003) at baseline. The Support for Feelings subscale measures emotion-focused support seeking and includes items assessing participants’ use of others to listen to their feelings or to provide understanding (e.g., “You told other people what made you feel the way you did”). Support for Actions measures problem-focused support seeking and assesses the use of others for assistance in seeking solutions to the current problem, such as seeking advice, information, or assistance with tasks (e.g., “You talked to someone who could help you figure out what to do”). For both types of social support seeking, participants were instructed to indicate how often they used the each of the strategies in response to problems or to feeling “upset about things.” A four-point Likert-type scale is used to capture how often participants use the measured strategies, with responses ranging from “never” to “most of the time.” Research into the CCSC psychometric properties has demonstrated its consistency with other measures of coping and its high internal consistency (Ayers et al., 1996). Coefficient alphas in the current study were .86 and .81 for Support for Feelings and Support for Actions, respectively. Higher scores reflect higher levels of seeking social support.

Data Analytic Plan

To test the primary prospective moderation hypotheses, we used hierarchical linear regression. Depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms were each regressed on a social support seeking variable (i.e., either emotion-focused or problem-focused support seeking), rumination, and the interaction between the social support seeking variable and rumination. Initial models controlled for participant age and sex. There were a total of four regression models (i.e., an emotion-focused model and a problem-focused model for depression and for anxiety). Emotion-focused support seeking and problem-focused support seeking were tested in separate models given concerns about collinearity, power, and for ease of interpretation. Examination of skewness and kurtosis for all primary study variables revealed evidence of non-normality for emotion-focused support; a square root transformation was applied. Predictors and the moderator were centered and the two interaction terms (i.e., emotion-focused support seeking by rumination, problem-focused support seeking by rumination) were formed as the cross-product of the centered variables. For each regression model, baseline levels of the outcome variables were entered in step one. Main effects of rumination and the social support seeking variable along with covariates were entered in step two, and the interaction term was entered in step three. All marginal and significant interaction terms were probed using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2012); simple slopes were tested using the Johnson Neyman procedure which identifies the specific levels of the moderator variable at which the predictor becomes significantly related to the outcome variable.

Preliminary correlational analyses revealed a large correlation between emotion-focused and problem-focused support seeking (see Table 1), leaving open questions about the unique contribution of each factor. Thus, we elected to conduct post-hoc analyses that combined both support seeking factors in the same model in order to determine their independent contributions to anxiety and depression. It is important to note that these exploratory analyses must be interpreted with caution; they are under-powered given the high correlation between predictors.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

| Measure | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Depression - CDI | -- | 0.85 *** | 0.89 *** | 0.75 *** | 0.84 *** | 0.78 *** | −0.37 *** | −0.34 *** | 0.69 *** |

| 2. T2 Depression -CDI | -- | 0.82 *** | 0.87 *** | 0.75 *** | 0.84 *** | −0.35 *** | −0.33 *** | 0.56 *** | |

| 3. T1 Depression - RADS-2 | -- | 0.82 *** | 0.84 *** | 0.77 *** | −0.42 *** | −0.38 *** | 0.66 *** | ||

| 4. T2 Depression - RADS-2 | -- | 0.73 *** | 0.81 *** | −0.34 *** | −0.31 ** | 0.50 *** | |||

| 5. T1 Anxiety | -- | 0.87*** | −0.30 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.70 *** | ||||

| 6. T2 Anxiety | -- | −0.31 ** | −0.25 ** | 0.60 *** | |||||

| 7. T1 Emotional Support | -- | 0.80 *** | −0.16 | ||||||

| 8. T1 Problem Support | -- | −0.13 | |||||||

| 9. T1 Rumination | -- | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.8(8.8) | 9.5(8.6) | 60.2(17.0) | 56.8(17.1) | 10.8(7.7) | 9.5(7.7) | 2.5(1.0) | 2.4(0.8) | 20.9(6.8) |

| Actual Range | 0–36 | 0–39.5 | 30 – 97 | 29 – 108 | 0–27 | 0–28 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 10–39 |

| Possible Range | 0–52 | 0–52 | 29–116 | 29–116 | 0–37 | 0–37 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 10–40 |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Means for the CDI, RADS-2, and RCMAS in the current sample were all well within one standard deviation of the standardization sample mean (Kovacs, 2001; Reynolds, 2002; Reynolds & Richmond, 1985). All correlations between the measures of emotion-focused and problem-focused support seeking and measures of depression and anxiety were significant and small to medium in size; higher levels of emotion-focused support seeking and problem-focused support seeking were associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety. Correlations between rumination and depression and anxiety were all significant, large, and positive – higher levels of rumination were associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety.

Primary Analyses

Emotion-Focused Support Seeking

Results for emotion-focused support seeking are presented in Table 2. We hypothesized that rumination would moderate the relationship of emotion-focused support seeking to depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms, such that emotion-focused support seeking would be less helpful for adolescents who scored higher on rumination than for those who scored lower on rumination.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Models

| Model

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion-Focused | Problem-Focused | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Depression | Anxiety | Depression | Anxiety | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Measure | B | SEB | β | B | SEB | β | B | SEB | β | B | SEB | β |

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||

| Outcome Variablea | .86*** | .05 | .86*** | .87*** | .07 | .87*** | .91*** | .07 | .91*** | .87*** | .05 | .87*** |

| ΔR2 | .74*** | .75*** | .74*** | .75*** | ||||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||

| Sex | .19t | .09 | .10t | -- | -- | -- | .20* | .09 | .10* | -- | -- | -- |

| Adolescent Age | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.08t | .05 | −.09t | -- | -- | -- |

| Rumination | −.01 | .01 | −.06 | −.02 | .08 | −.02 | −.01 | .01 | −.06 | −.02 | .08 | −.02 |

| Support Seekingb | −.08 | .17 | −.03 | −1.38 | 1.20 | −.06 | −.03 | .06 | −.03 | −.40 | .46 | −.04 |

| ΔR2 | .01 | .003 | .02t | .002 | ||||||||

| Step 3 | ||||||||||||

| Rumination* Support | .07** | .02 | .15** | .34t | .17 | .09t | .02* | .01 | .11* | .02 | .06 | .02 |

| Seeking | ||||||||||||

| ΔR2 | .02** | .01t | .01* | .000 | ||||||||

| Total R2 | .77*** | .76*** | .77*** | .75*** | ||||||||

Values in this row are taken from the regression of the targeted outcome variable (i.e., Depression or Anxiety) on the corresponding variable at Time 1.

Values in this row represent the regression of outcome variable on the targeted social support seeking variable (i.e., Emotion- or Problem-Focused).

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

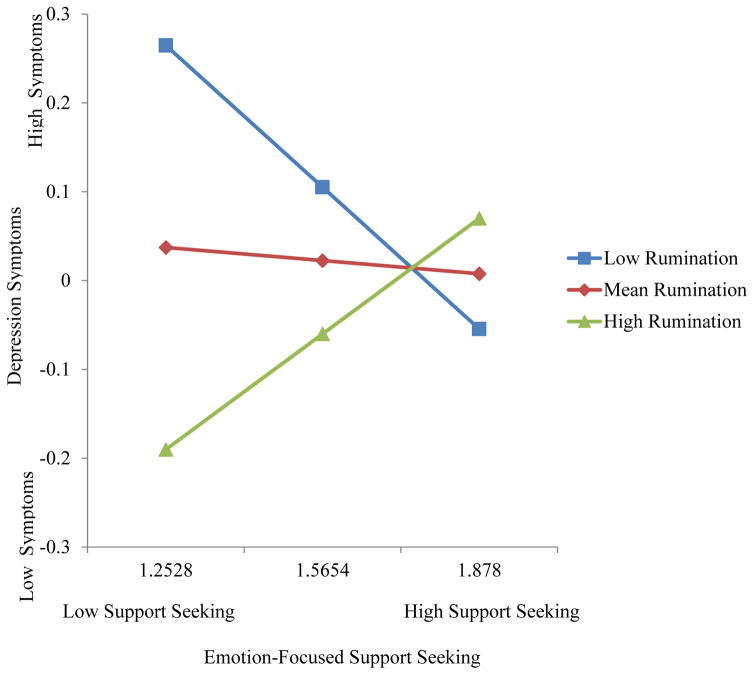

For depression symptoms, age was not a significant predictor and was dropped; sex was marginally significant and was retained in the model. The interaction between emotion-focused support seeking and rumination significantly predicted depression symptoms, B = 0.07, SE = .02, p = .001, and accounted for 2% of the variance, ΔR2 = .02. Emotion-focused support seeking was significantly, negatively associated with depression symptoms at low levels of rumination (i.e., beginning at .75 SD below the mean), B = −0.39; SE = 0.19, p = .04, and significantly, positively associated with depression symptoms at high levels of rumination (beginning at 1.18 SD above the mean), B = .50, SE = .24, p = .04 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Depression symptoms: Simple slopes of emotion-focused support seeking at low, mean, and high levels of rumination.

For anxiety symptoms, neither adolescent age nor sex were significant predictors; both covariates were dropped. A marginally significant interaction between emotion-focused support seeking and rumination emerged, B = .34, SE = .17, p =.05. The interaction accounted for 1% of the variance in anxiety symptoms, ΔR2 = .01. Similar to the findings for depression symptoms, emotion-focused support seeking was significantly and negatively associated with anxiety at low levels of rumination (i.e., beginning at .75 SD below the mean); B = −2.99; SE = 1.43, p = .04. However, emotion-focused support was unrelated to anxiety at mean or high levels of rumination. The general pattern of simple slopes was very similar to those for depression symptoms presented in Figure 1. The results for both depression and anxiety symptoms suggest that while emotion-focused support seeking is predictive of fewer internalizing problems at low levels of rumination, it loses its adaptive effects as levels of rumination increase, and may even become maladaptive for individuals who report high levels of rumination.

Problem-Focused Support Seeking

Results for problem-focused support seeking are presented in Table 2. For the depression model, age and sex were marginal and significant predictors respectively, and were retained in the model. The interaction between problem-focused support seeking and rumination was significant for depression symptoms, B = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = .03, and accounted for 1% of the variance, ΔR2 = .01. Problem-focused support seeking was significantly negatively related to depression symptoms at low levels of rumination (i.e., beginning at 1.6 SD below the mean), B = −.20; SE = .10, p = 0.04. Beginning at 1.82 SD above the mean, problem-focused support seeking was marginally positively related to depression symptoms, B = .21; SE = .12, p = 0.09; however, this effect never reached significance within the actual range of data in the current sample. The overall pattern of simple slopes was again very similar to those presented in Figure 1. These data suggest that the effects of problem-focused support seeking on depression symptoms also vary as a function of rumination, such that problem-focused support seeking is associated with fewer depression symptoms at low levels of rumination, but loses its adaptive effects when individuals report very high levels of rumination. There were no significant effects for anxiety.

Exploratory analyses

Hierarchical regression models combining both emotion-focused and problem-focused support seeking for depression and for anxiety revealed that the interaction for emotion-focused support seeking, but not problem-focused support seeking, was significant; B = .07, SE = .03, p = .04 and B = .63, SE = .27, p = .02 for depression and anxiety, respectively. Probing of significant interactions revealed nearly identical results for both depression and anxiety. Emotion-focused support seeking was significantly negatively associated with symptoms at low levels of rumination for both depression (i.e., beginning at 1.6 SD below the mean), B = −.84; SE = .42, p = .049, and anxiety (beginning at .75 SD below the mean), B = −4.88; SE = 2.30, p = .04. At extremely high levels of rumination, emotion-focused support was marginally positively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms (i.e., beginning at 2.25 SD above the mean); B = .94; SE = .57, p = .099 for depression and B = 7.86; SE = 4.65, p = .094 for anxiety. These findings suggest that emotion-focused, but not problem-focused, support seeking uniquely predicts both depression and anxiety symptoms in combination with rumination. Further, as in the primary analyses, emotion-focused support seeking was adaptive at low levels of rumination but loses its adaptive effects as rumination increases.

Discussion

The current study examined how two potentially modifiable risk and protective factors – rumination and social support seeking – interacted to predict depression and anxiety symptoms in early adolescents. We found that the relationship between support seeking and symptoms varied according to adolescents’ levels of rumination. Emotion-focused support seeking predicted fewer subsequent depression and anxiety symptoms among adolescents who reported low levels of rumination, but this adaptive effect weakened for both depression and anxiety as rumination levels increased. For depression symptoms, emotion-focused support seeking even predicted more symptoms of depression at high levels of rumination. Similarly, problem-focused support seeking predicted fewer symptoms of depression (but not anxiety) at low levels of rumination, and marginally predicted more symptoms of depression (but not anxiety) at very high levels of rumination. Taken together, these results suggest that seeking social support for emotions or problems are generally helpful coping strategies for adolescents engaging in low levels of rumination, but are less helpful and potentially prolongs or increases symptoms among adolescents reporting high levels of rumination. These findings suggest that cognitive risk factors such as rumination may have important implications for adolescents’ abilities to use social support effectively, and highlight the importance of using a nuanced approach to the study of social support seeking.

Relations to past findings

The current findings are in line with previous research that suggests that rumination has negative implications for individuals’ social support and interpersonal relations including perceived social support (Abela et al., 2004), satisfaction with social support (Flynn, Kecmanovic, & Alloy, 2010), and interpersonal problem solving (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995). This study also complements findings in related literature that has demonstrated that the effects of social support seeking can vary as a function of contextual risk factors, such as exposure to community violence (e.g., Hammack et al., 2004). Further, the current study offers one potential explanation for some of the inconsistencies in the existing literature on social support seeking - the role of cognitive risk factors such as rumination. Despite being one of the most frequently measured coping strategies (Skinner et al., 2003), studies of social support seeking have yielded relatively inconsistent findings with respect to youths’ mental health problems (e.g., Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009; Gonzales et al., 2001; Landis et al., 2007; Sandler et al., 1994; Skinner et al., 2003). While a number of factors likely contribute to the variability in findings (e.g., diversity of measures used, inconsistencies in definitions of social support seeking across measures; Compas et al., 2001, Skinner et al., 2003), the current study suggests that cognitive risk factors like rumination may relate to whether social support seeking is adaptive. Unmeasured variability in youths’ rumination and other cognitive, behavioral, or interpersonal risk factors might account for some of the inconsistencies in past work.

Why effects vary by rumination

Although not examined in this study, it is interesting to speculate as to why the effects of social support seeking on early adolescents’ depression and anxiety symptoms changed as a function of adolescents’ levels of rumination. First, adolescents who tend to engage in high levels of rumination may also be more likely to engage in co-rumination (i.e., excessive, repetitive discussion of problems) when seeking support from others. Although co-rumination predicts improvements in perceived relationship quality, it has also been shown to predict increases in depression and anxiety (Rose et al., 2007). If adolescents who report high levels of rumination tend to seek social support in the form of co-rumination, this may in part explain why social support seeking (especially emotion-focused support) is predictive of more rather than fewer problems for these youths. Rumination and co-rumination have indeed been shown to be moderately positively correlated (Rose, 2002), providing some support for this assertion. The moderate correlation, however, indicates that other processes may also be at play. For example adolescents who ruminate frequently are more likely to express dissatisfaction with their social support than their peers who ruminate less often (Flynn et al., 2010). Seeking social support for help with problems or negative emotions, only to experience the support as inadequate, may lead to increases in depression and anxiety symptoms.

It is also possible that adolescents who frequently ruminate, given their tendency to focus on negative symptoms, may behave in ways during social interactions that are disruptive to their interpersonal relationships, which in turn may precipitate or exacerbate symptoms of depression and anxiety. This would be consistent with the interpersonal stress generation theory of depression, which hypothesizes that depressed individuals and individuals at risk for depression (i.e., people with underlying cognitive, affective, and/or interpersonal vulnerabilities to depression such a ruminative response style) tend to behave in ways that generate stress in their relationships (e.g., Coyne, 1976; Hammen, 1991; Flynn et al., 2010). Adolescents who engage in high levels of rumination may focus on their negative emotions and symptoms when interacting with others; this negative focus may be experienced as unpleasant or stressful by their friends and loved ones. Further, adolescents who engage in high levels of rumination are also more likely to engage in excessive reassurance seeking (Weinstock & Whisman, 2007). Such persistent seeking of reassurance about their worth may also be experienced as aversive or stressful by close others. As friends and loved ones come to experience interactions with these adolescents as negative, they may express dissatisfaction with the relationship or begin to withdraw support, which in turn may exacerbate adolescents’ depression and anxiety symptoms.

Variability across findings

As anticipated, the moderating effects of rumination were more consistent for emotion-focused support seeking than for problem-focused support seeking. For example, rumination moderated the relationship between problem-focused support seeking and depression symptoms but not anxiety symptoms. Further, post-hoc analyses indicated that emotion-focused support, but not problem-focused support, uniquely predicted depression and anxiety symptoms in combination with rumination. Given problem-focused support seeking’s focus on information, advice, and problem-solving rather than on emotions, it is reasonable to expect that rumination may have fewer negative implications for this more practical and solution-focused form of support. By seeking support that is focused on gathering information and generating potential solutions, adolescents may interrupt their ruminative focus on negative emotions and symptoms, thereby reducing or eliminating any negative effects of rumination on the implications of problem-focused support seeking for depression or anxiety symptoms.

However, some evidence that rumination may attenuate the potential benefits of even problem-focused support seeking did emerge for depression symptoms in the primary analyses. This finding is in line with previous literature that has shown that engaging in rumination has negative implications for individuals’ problem solving skills such as the generation of less effective solutions, biased interpretations of hypothetical problem situations, a greater likelihood of rating their own problems as unsolvable, and a lower likelihood of implementing generated solutions (e.g., Lyubomirksy & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Watkins & Baracaia, 2002). Perhaps adolescents who engage in high levels of rumination are also more likely to reject the advice or solutions generated by their support person, view the information received as unhelpful or inadequate, or fail to act upon the suggestions provided. Such negative feedback and/or failure to act may be perceived negatively by the support person, who then may be less likely to provide support in the future, thus leading to increases in depression symptoms. However, it is important to note that the correlations between emotion-focused support seeking and problem-focused support seeking were quite large in size. Perhaps the significant finding for problem-focused support seeking was driven primarily by co-occurring emotion-focused support, rather than a unique effect of problem-focused support seeking. The results of the post-hoc analyses support this assertion, although strong interpretations must be tempered given the low power for these particular analyses given the highly correlated predictors. Replication of these findings in other samples as well as greater attention to what adolescents actually do when seeking support from others will serve to clarify to what extent the negative implications of rumination for seeking social support are unique to emotion-focused support seeking, or extend to problem-focused support seeking as well.

It is also important to note that findings were generally stronger for depression symptoms than for anxiety symptoms. Although this is contrary to our hypotheses (we expected similar findings across symptom domains), it is not entirely unexpected that the findings were weaker for anxiety. First, the construct of rumination was originally developed and assessed specifically for the prediction of depression (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), and the majority of the rumination literature has focused on depression and depression symptoms. Although there is recent work indicating that rumination may be relevant for anxiety and may serve as a transdiagnostic risk factor (e.g., McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011), the body of work linking rumination to mental health problems is stronger for depression. Further, rumination typically focuses on the past or present (e.g., problems that have already occurred, current negative feelings or symptoms) whereas anxiety is typically conceptualized as having a future-orientation (e.g., anticipating negative events or consequences that have not yet occurred; Alloy et al., 1990). This discrepancy in time-orientation could also partially account for the weakness in relations – either direct or interactive – between rumination and anxiety.

Low levels of rumination and support seeking indicate high risk

Across the various moderation effects, it appears that the adolescents who are most prone to symptoms of depression and anxiety are those that score low both on rumination and on social support seeking. In some ways this is counter-intuitive, as we would expect that scoring low on rumination would be associated with fewer rather than more symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, it is worth noting that there are no significant main effects of rumination on depression or anxiety in this sample, only the significant interactive effects reported above. This pattern of findings suggests that for early adolescents who engage in low levels of rumination, it may be particularly important to seek out social support, especially emotion-focused support. Alternatively, perhaps low levels of social support seeking in response to stress reflect an inadequate social support network – it is difficult to seek support when you are unsure of who you should turn to. It is also possible that adolescents who score low on both rumination and social support seeking may be doing so deliberately – perhaps they are engaging in avoidant coping (i.e., intentionally avoiding thinking and talking about their feelings and problems), which has been consistently linked to depression and anxiety (e.g., Compas et al., 2001; Krause, Mendelson, & Lynch, 2003; Krause, Kaltman, Goodman, & Dutton, 2008). Thus, while not seeking social support may be a helpful coping choice for individuals who ruminate frequently (i.e., because they may not be able to effectively use their social support networks), not seeking support from others may reflect a poor coping choice and/or a lack of sufficient close social ties for adolescents who do not tend to ruminate.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Although the current study has a number of strengths such as the use of well-established measures and a longitudinal design, the study also has a number of important limitations. First, all variables were assessed through adolescent report; shared method variance may partially account for the relations between study variables. Second, participants were primarily of Caucasian, Non-Hispanic descent. The sample is representative of the racial and ethnic make-up of the communities from which it was recruited, but the conclusions from this study may not extend to other populations. Future work should examine whether rumination moderates the relationship of support seeking to depression and anxiety in childhood or late adolescence, and across different ethnic, racial, or cultural groups. Further, given the limited sample size of the current study (i.e., N = 118), we were unable to examine developmental shifts or gender differences in our interactive effects. Exploring developmental shifts in the relations between rumination, support seeking, and mental health even within early adolescence (e.g., in 6th vs. 7th vs. 8th grade) as well as gender differences in the moderation models would yield richer information about how these relations unfold over time and across groups. In addition, while the presence of stress was implied in the social support seeking measure used (i.e., participants indicated how frequently they used these strategies when facing problems or feeling upset), we did not directly assess stress. Including a measure of stress in future work would allow for an assessment of the current models in a vulnerability-stress framework, and could more directly investigate the adaptiveness of seeking social support in direct response to stress. Finally, it is important to consider that the interactive effects in this study were small, accounting for only one to two percent of variance in symptoms. Conclusions about the importance of these findings and implications for clinical applications must be tempered given the small effect sizes. Interactive effects of this magnitude are typical for psychology, however, as most interactions in the social sciences account for a few percentage points of variance (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

Despite the limitations of the study, the findings suggest many implications for future research, intervention development, and clinical practice. First, this study highlights the importance of considering individuals’ cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal habits (such as a tendency to ruminate) when studying social support seeking in youth. Although social support is typically conceptualized as a protective resource, risk factors such as rumination may impede individuals’ abilities to use their social support resources effectively. Researchers interested in understanding how social support seeking relates to the development, maintenance, or exacerbation of depression or anxiety symptoms in youth should explore the potential effects of cognitive vulnerability factors such as rumination, pessimistic explanatory style or dysfunctional attitudes in future work. Similarly, researchers should also consider the potential moderating effects of interpersonal vulnerability factors such as co-rumination and reassurance seeking on the relations between social support seeking and mental health. Finally, the current study suggests that researchers interested in the effects of social support seeking should consider using or developing assessment procedures that capture the details of the pursuit and receipt of social support. A better sense of how exactly individuals go about seeking support and what types of support they ultimately receive will further clarify when and how social support can function as an adaptive resource for young people.

Clinical Implications

Despite evidence that social support seeking was associated with higher levels of symptoms among some early adolescents, the current study should not be interpreted as a recommendation against the use of social support seeking as a coping strategy in clinical settings. In fact, the current findings show that support seeking, especially emotion-focused support seeking, is a helpful strategy for adolescents who engage in low levels of rumination. What this study suggests is rather that program developers and clinicians should attend to cognitive risk factors when evaluating protective resources and making recommendations regarding social support. Interventionists must ensure that individuals use their support systems in effective ways – identifying the presence of cognitive risk factors like rumination may help clinicians meet this goal. For adolescents reporting high levels of rumination, clinicians may wish to directly address rumination prior to encouraging participants to seek out support, and may wish to enhance adolescents’ interpersonal skills to help them use their support networks effectively. Addressing factors such as rumination and social support in early adolescence specifically may be particularly important for prevention efforts, given the spikes in rates of depression and related conditions during the transition to middle and late adolescence.

Summary

In summary, the current study provides one potential explanation for the variability in existing literature on the effects of social support seeking on adolescents’ mental health – the moderating effects of cognitive risk factors such as rumination. Future work examining individual characteristics that impede adolescents’ ability to benefit from social support seeking will further the field’s understanding of the roles of both cognitive and interpersonal factors in the development of anxiety and depression, and will inform the development of appropriate prevention and treatment programs for these disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families, school counselors, and teachers who participated in this project.

Funding

This project was supported by National Institute of Mental Health [grant number MH52270].

References

- Abela JR, Hankin BL. Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(2):259. doi: 10.1037/a0022796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR, Hankin BL, Sheshko DM, Fishman MB, Stolow D. Multi-wave prospective examination of the stress-reactivity extension of response styles theory of depression in high-risk children and early adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40(2):277–287. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9563-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR, Vanderbilt E, Rochon A. A test of the integration of the response styles and social support theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23(5):653–674. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.5.653.50752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Kelly KA, Mineka S, Clements CM. Comorbidity in anxiety and depressive disorders: A helplessness-hopelessness perspective. In: Maser JD, Cloninger CR, editors. Comorbidity in anxiety and mood disorders. 1990. pp. 499–543. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers TS, Sandler IN, West SG, Roosa MW. A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality. 1996;64(4):923–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;32(3):483. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56(2):267–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Gillham JE, Seligman ME. Gender, anxiety, and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study of early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(2):307–327. doi: 10.1177/0272431608320125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(1):87–127. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cox SJ, Mezulis AH, Hyde JS. The influence of child gender role and maternal feedback to child stress on the emergence of the gender difference in depressive rumination in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(4):842–852. doi: 10.1037/a0019813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85(2):186–193. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RN, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and nonruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24(6):699–711. doi: 10.1023/A:1005591412406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evraire LE, Dozois DJ. An integrative model of excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking in the development and maintenance of depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(8):1291–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M, Kecmanovic J, Alloy LB. An examination of integrated cognitive-interpersonal vulnerability to depression: The role of rumination, perceived social support, and interpersonal stress generation. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34(5):456–466. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9300-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Weersing VR. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in youth: Implications for treatment and prevention. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(4):293–306. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, Cunningham JA. The impact of racial discrimination and coping strategies on internalizing symptoms in African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(4):532–543. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Reivich KJ, Brunwasser SM, Freres DR, Chajon ND, Kash-MacDonald V, … Seligman MEP. Evaluation of a group cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for young adolescents: A randomized effectiveness trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(5):621–639. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.706517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Symptoms versus a diagnosis of depression: Differences in psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:90100. doi: 10.1037/0022006X.63.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Tein JY, Sandler IN, Friedman RJ. On the limits of coping interaction between stress and coping for inner-city adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2001;16(4):372–395. doi: 10.1177/0743558401164005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL, Richards MH, Luo Z, Edlynn ES, Roy K. Social support factors as moderators of community violence exposure among inner-city African American young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):450–462. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):555–561. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Stone L, Ann Wright P. Corumination, interpersonal stress generation, and internalizing symptoms: Accumulating effects and transactional influences in a multiwave study of adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(1):217–235. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper] 2012 Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Joiner TE, Metalsky GI, Katz J, Beach SR. Depression and excessive reassurance-seeking. Psychological Inquiry. 1999;10(3):269–278. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1004_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Dutton MA. Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure: A longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(1):83–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Mendelson T, Lynch TR. Childhood emotional invalidation and adult psychological distress: The mediating role of emotional inhibition. Child abuse & neglect. 2003;27(2):199–213. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00536-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis D, Gaylord-Harden NK, Malinowski SL, Grant KE, Carleton RA, Ford RE. Urban adolescent stress and hopelessness. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(6):1051–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater B, Thompson K, Gruppuso V. Co-occurring trajectories of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and oppositional defiance from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(6):719–730. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.694608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez CM, Felton JW, Driscoll KA, Kistner JA. Brooding rumination and internalizing symptoms in childhood: Investigating symptom specificity in a multi-wave prospective study. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2012;5(3):240–253. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2012.5.3.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Zelazo LB. Research on resilience: An integrative review. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 510–549. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(1):176. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49(3):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Fokke M, Kwik D. The ruminative response style in adolescents: An examination of its specific link to symptoms of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2009;33(1):21–32. doi: 10.1007/s10608-007-9120-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(1):561–570. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):569–582. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-2: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale Manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ. Co–rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development. 2002;73(6):1830–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Carlson W, Waller EM. Prospective associations of co-rumination with friendship and emotional adjustment: Considering the socioemotional trade-offs of co-rumination. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(4):1019–1031. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, Tein JY, Kwok OM, Haine RA, … Griffin WA. The Family Bereavement Program: Efficacy evaluation of theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):587–600. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein JY, West SG. Coping, stress, and the psychological symptoms of children of divorce: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Child Development. 1994;65(6):1744–1763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt ME, Bagwell CL. The protective role of friendships in overtly and relationally victimized boys and girls. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53(3):439–460. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2007.0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(2):216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52(2):145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(4):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel W, Vasey MW, Gonda T, Stern T. Executive function deficits, rumination and late-onset depressive symptoms in older adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32(4):474–487. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9034-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ED, Baracaia S. Rumination and social problem-solving in depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40(10):1179–1189. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock LM, Whisman MA. Rumination and excessive reassurance-seeking in depression: A cognitive–interpersonal integration. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2007;31(3):333–342. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9004-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]