Abstract

The optimal timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis in patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) is currently unknown. This transition period is one of exceptionally high vulnerability for patients; annual mortality rates in stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) through the first year of maintenance dialysis exceed 20%. The results of the Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study, the only randomized trial to have tested the impact of dialysis initiation at two different levels of kidney function on outcomes, demonstrated no significant difference in survival or other patient-centered outcomes between treatment groups. These data have challenged the established paradigm of using estimates of glomerular filtration as the primary guide for initiation of maintenance dialysis and illustrate the compelling need for research to optimize the high risk transition period from CKD to ESRD. This article reviews the findings of the IDEAL study and summarizes the evolution of research findings, updated clinical practice guidelines, and trends in dialysis initiation practices in the United States in the 6 year since publication of the results from IDEAL. Complementary strategies to the use of eGFR to optimally time the initiation of maintenance dialysis and potentially improve patient-centered outcomes are also considered.

Keywords: Kidney function, glomerular filtration rate, mortality, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, epidemiology, clinical outcomes

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, more than 114,000 individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) initiate maintenance dialysis each year.1 The period spanning advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) through initiation of maintenance dialysis and the first year of treatment is characterized by exceptionally high risk for adverse patient outcomes. The mortality rate for patients with stage 5 CKD exceeds 20 per 100 patient-years, and in the first three months after dialysis initiation approaches 50 per 100 patient-years.1 Hospitalization rates in the first three months after the start of dialysis therapy exceed 30 days per patient-year, and the incidence and duration of hospitalization during the first year of dialysis treatment far exceeds that for the period following the first year.2,3 There has thus been considerable interest within the nephrology community in identifying risk factors that may identify patients who may be at particularly high risk, and furthermore in identifying interventions that may help optimize the transition for patients with advanced CKD from medical management to treatment with dialysis therapy.

One key contributor to poor outcomes during the transition to ESRD is inadequate medical and psychosocial preparation for dialysis.4–9 An important underlying cause of such inadequate preparation is limited understanding on the part of the nephrology community regarding the optimal timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis. Likely in part due to the influence of clinical practice guidelines published in the 1990s emphasizing the importance of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in determining when to initiate renal replacement therapy, the last decade of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first century witnessed an inexorable rise in the mean eGFR at which individuals with ESRD in the United States have initiated dialysis.1,10 Although mortality rates for ESRD patients in the United States have recently declined, it remains uncertain to what extent, if any, the trend in “earlier” initiation of dialysis has contributed to such improvements in patient outcomes. Furthermore, numerous observational studies published over the past 15 years have sought to investigate the association of eGFR at dialysis initiation with subsequent clinical outcomes, and with few exceptions, have consistently shown a higher mortality risk with higher eGFR at dialysis start.11 In contrast, studies that have employed timed urea or creatinine clearances rather than serum creatinine-based estimating equations to measure GFR have suggested that higher GFR at dialysis initiation may be associated with lower risk for poor outcomes.5,12,13

In the face of persistent uncertainty regarding the optimal timing of dialysis initiation, and seeking to address recognized limitations of non-randomized observational studies, the Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study was launched in the first decade of the twentieth century, and the results – eagerly anticipated by the nephrology community – were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2010.14 In this article, we summarize the findings of the IDEAL study, and discuss the evolution of research, clinical practice guidelines, and trends in dialysis initiation practices in the United States in the 6 year since publication of the results from IDEAL. We further describe considerations in implementing complementary strategies to the use of eGFR in assisting nephrologists, patients, and caregivers to optimally time the initiation of maintenance dialysis.

THE IDEAL STUDY

The IDEAL study was conducted between July 2000 and November 2008, and enrolled a total of 828 adults with progressive advanced CKD, defined as an eGFR (calculated by the Cockcroft-Gault equation) of 15 mL/minute/1.73 m2 of body surface area. Patients were recruited at 32 centers in Australia and New Zealand and were randomized to initiate dialysis at an eGFR of 10–15 ml/min/1.73m2 (termed “early start”) or when the eGFR had fallen to 5–7 ml/min/1.73m2 (termed “late start”). Patients were followed for a median period of 3.6 years for the primary outcome of all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included cardiovascular events, infectious complications, hospitalization rate and days, treatment-associated complications such has the use of temporary dialysis catheters, health-related quality of life, and economic impact.15 The landmark primary finding in the primary report from the IDEAL study was that there was no significant difference between the study groups in all-cause mortality, or in any clinically important secondary outcome, including hospitalizations cardiovascular events. A follow-up economic analysis of IDEAL similar showed that although there were significantly higher dialysis-related costs associated with early start, overall healthcare costs were not significantly different between the two intervention arms.16 There were additionally no substantial differences between the study groups in health-related quality of life, as measured by the well-validated SF-36 survey instrument. A pre-specified subgroup analysis of the IDEAL examined the effects of early versus late initiation on clinical outcomes among patients whose planned modality at the time of randomization was peritoneal dialysis, and found comparable results to those seen in the main analysis.17 Finally, results from a cardiac sub-study involving 182 IDEAL participants showed no effect of randomized group assignment on echocardiographic measures of cardiac structure or function, including left ventricular ejection fraction, left ventricular mass, or left atrial volume.18

A number of limitations of the IDEAL study have been noted and described by numerous commentators since the publication of the IDEAL results, and should be considered when interpreting the results of the trial for implementation in clinical practice in the United States.19–23 First, among patients assigned to the early start group, nearly 20% initiated dialysis with an eGFR of <10 ml/min/1.73m2; conversely, among those assigned to the late start group, 76% initiated dialysis with an eGFR >7 ml/min/1.73m2. The end result of these protocol violations was a narrowing of the intended between-group separation in the eGFR at the time of dialysis initiation, to 12.0 ml/min/1.73m2 in the early start group and 9.8 ml/min/1.73m2 in the late start group, a difference of only 2.2 ml/min/1.73m2. Although this small difference in eGFR at dialysis start has been the subject of extensive discussion, it should be noted patients allocated to the late-start group initiated dialysis nearly 6 months later on average compared to those randomized to the early start group, a fact that has been pointed out by the study investigators in response to such criticism.24 A second limitation of IDEAL pertains to generalizability to the United States population of patients with ESRD. Participants in IDEAL were predominantly white (given the racial/ethnic makeup of the populations of Australia and New Zealand), had much less cardiovascular morbidity and a lower prevalence of other coexisting illnesses compared to the U.S. ESRD population, and had higher probability of having received pre-dialysis nephrology care. Furthermore, more than half of the early start group were treated with peritoneal dialysis as the initial dialysis modality, and few patients in either group initiated dialysis using a central venous catheter. These numbers are in stark contrast to the incident dialysis population in the United States, where still greater than 80% of patients start dialysis using a central venous catheter, and over 90% are treated with in-center hemodialysis. Finally, of patients in late start group who initiated dialysis prior to the goal eGFR of 5–7 ml/min/1.73m2, there was relatively little detail collected by the study investigators regarding the actual indications that prompted dialysis initiation; 73% of this group were recorded as starting due to “uremia,” but the constituent signs and symptoms that prompted these initiations remain unknown.

The publication of the results from the IDEAL trial was a landmark event in nephrology research; given the extraordinary effort, time, and cost that went into conducting the study, it is unlikely that another randomized trial of similar size and scope will be undertaken in the foreseeable future aimed at evaluating the effect of eGFR at dialysis initiation on subsequent clinical outcomes. Given the null results of the trial, and acknowledging the many limitations of the study as previously discussed, what was the core message that emerged for the community of clinical nephrologists who must make decisions each day of when to recommend dialysis initiation for their patients? What many have taken away from the study is that among asymptomatic patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (i.e. without clinical evidence of appearance of components of the uremic syndrome), initiation of dialysis may be safely postponed until uremic signs or symptoms appear.5,6,19 In other words, there is no absolute level of glomerular filtration rate at which dialysis must be started in the absence of other clinical indications. A corollary to this message, however, is that dialysis should not be delayed in patients with other relative indications (such as development or uremic symptoms, hyperkalemia, or volume overload), simply because the level of residual kidney function may be “too high.”5 Along with an enhanced focus on shared decision-making among patients, providers, and caregivers in decisions regarding dialysis initiation timing and practices, these core messages emerging from interpretation of the IDEAL study results have ultimately been embodied in the most recent iterations of clinical practice guidelines from the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) in the U.S., and the Canadian Society of Nephrology.25,26

TIMING OF DIALYSIS INITIATION AND MORTALITY–EVIDENCE FROM STUDIES SINCE IDEAL

Although the IDEAL study remains the only large randomized controlled trial published to date which has specifically aimed to evaluate the benefit of initiation of dialysis at a high versus low level of eGFR, research exploring various aspects of the timing of dialysis initiation has continued in the 6 years since the publication of IDEAL. A number of observational cohort studies using large datasets have sought to test modified versions of the hypothesis tested in the IDEAL study, while attempting to improve upon the potential for biases present in previous observational studies of dialysis initiation timing, including lead-time bias and confounding by indication. Using data from the U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS), Wright et al27 studied nearly 900,000 patients initiating dialysis from 1995 to 2006 and found that compared to those starting dialysis with eGFR 5–10 ml/min/1.73m2, those starting with eGFR <5 ml/min had a 12% lower mortality risk. Similarly, Rosansky et al28 used a restricted cohort design to select relatively healthy group of patients (age 20–64 years, without diabetes) from the USRDS, hypothesizing that restricting analyses to such a group would prevent selection biases that had confounded earlier observational studies and would more closely approximate the conditions of an RCT such as IDEAL. They furthermore performed a secondary restricted analysis on an even healthier subset of patients with serum albumin of ≥3.5 g/dL. The results of this study showed a dose dependent increase in mortality risk with increasing eGFR at dialysis initiation, with the greatest effect seen in the subgroup with serum albumin ≥3.5 g/dL.

Other recent studies have also attempted to address concerns regarding selection bias and residual confounding found in prior observational studies through the use of contemporary statistical techniques. Crews et al29 hypothesized that a major source of residual confounding in observational studies published prior to IDEAL was failure to accurately account for patient-level pre-dialysis health trajectories. Using a propensity score-matching approach that incorporate numerous pre-dialysis clinical factors, these investigators again analyzed USRDS data to compare early (eGFR of >10 ml/min/1.73m2) versus late (eGFR <10 ml/min/1.73m2) with respect to all-cause and cause-specific mortality and hospitalization risk. The primary results in the propensity-matched cohort was that early initiation was associated with an incrementally increased risk of all-cause mortality (11% increased risk) and hospitalization (3% increased risk). Other propensity score-matched analyses have found no benefit or harm to early dialysis initiation.30

Classically designed randomized controlled trials remain the gold standard method for evaluating the effect of an intervention on outcomes. However, randomized trials do have limitations, including threats to generalizability due to the healthier nature of patients who participate in trials, the well-established tendency of patients enrolled in clinical trials to alter their behavior due to awareness of being observed (known as the Hawthorne effect). In contrast, though not without limitations of their own, observational studies can be conducted using “real world” clinical datasets that may allow greater external generalizability. One way to overcome inherent shortcomings in observational studies such as selection bias and confounding while preserving their benefits compared to randomized trials is through causal inference modeling techniques such as the use of inverse probability weights and marginal structural models.31,32 Since publication of the results from the IDEAL study, a number of studies have sought to determine the impact of eGFR at dialysis initiation on subsequent clinical outcomes using these contemporary statistical methods, which effectively account for time-varying exposures and confounders, as well as avoiding lead-time and immortal time biases. Such retrospective comparative effectiveness studies conducted using data both from the U.S. and also from Europe have generally concluded that even among datasets utilizing real-world clinical data, there is no statistically significant survival effect comparing initiation of dialysis at higher versus lower eGFR.33,34

A number of recent published papers have assessed whether the impact of timing of dialysis initiation based on estimates of glomerular filtration on subsequent clinical outcomes may differ based on clinical or patient characteristics. As previously mentioned, a published post-hoc but pre-specificified subgroup analysis of the IDEAL trial analyzed the effect of early versus late initiation on the core clinical outcomes assessed in the original study among patients who had indicated that their planned initial dialysis modality was peritoneal dialysis.17 Although patients within this subgroup randomized to the late-start arm were less likely to end up treated with peritoneal dialysis compared to those randomized to the early-start arm, there did not seem to be an effect of eGFR at dialysis initiation on any outcome. Similarly, an observational cohort study of Korean patients initiating peritoneal dialysis also found no significant difference in mortality rate comparing patients with an eGFR at dialysis initiation of 5–10 ml/min/1.73m2 to those with eGFR of >10 ml/min/1.73m2.35 A recently published meta-analysis of studies that have included subgroup analyses of diabetic patients concluded that the effect of timing of initiation of dialysis does not differ between patients with versus without diabetes.36 Unfortunately, there remains a paucity of published data on whether there may be differences in the effect of timing of dialysis initiation on outcomes among subgroups of patients defined by other important patient and clinical variables, such as age, race/ethnicity, etiology of kidney disease, or burden of coexisting illnesses. Further studies are needed to investigate such subgroups to determine whether heterogeneity of effects exist–such differences, if proven could arm practicing nephrologists with more information with which to provide precision and targeted recommendations to their patients with advanced and progressive kidney disease.

Taken together, the results of cohort studies published since IDEAL suggest that notwithstanding the many fundamental limitations of observational study design vis a vis residual confounding and selection bias, there remains no compelling evidence that initiation of dialysis at high versus low eGFR as defined by IDEAL has a substantial impact on patient-centered outcomes. This is true in studies using contemporary and sophisticated statistical methods in attempts to avoid bias and reduce the impact of confounding, as well as those seeking to examine this question among important patient subgroups. Additionally, these studies raise the question of whether initiation of dialysis at even lower levels of glomerular filtration function as seen in IDEAL may be safe for patients, if not beneficial.

THE EVOLUTION OF CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES ON THE TIMING OF DIALYSIS INITIATION

Since publication of IDEAL, and explicitly influenced by both the IDEAL results and the growing body of observational data suggesting no benefit to early initiation of dialysis, clinical practice guidelines providing recommendations to clinicians on dialysis initiation decision-making have evolved considerably (Table 1). Even prior to 2010, the previous version of the NKF-KDOQI clinical practice guideline for initiation of dialysis published in 2006 avoided mention of a specific level of kidney function at which dialysis should definitely be initiated. Instead, this 2006 guideline recommended that once patients reach stage 5 CKD, clinicians should evaluate the benefits, risks, and disadvantages of beginning kidney replacement therapy. Furthermore, it stated that “particular clinical considerations and certain characteristic complications of kidney failure may prompt initiation before stage 5.”37 However, the most recent iteration of the KDOQI guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy, published in 2015, even more explicitly eschews a focus on eGFR and recommends that the decision to initiation maintenance dialysis should be based primarily upon assessment of specific complications of kidney disease, including signs and symptoms of uremia, protein-energy wasting, metabolic abnormalities, and volume overload, rather than based on a specific level of kidney function (Table 1).25 The stated rationale presented in the KDOQI guideline supported this revised statement is based largely on the results of the IDEAL trial, while admitting to the challenging nature of a decision-making approach based largely on a subjective assessment of signs and symptoms caused by advanced kidney disease, particularly in patients with coexisting illnesses which may themselves have symptoms mimic those classically associated with uremia.38

Table 1.

Current Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) on the Timing of Initiation of Maintenance Dialysis for Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease Published Since IDEAL

| Guideline | Statement |

|---|---|

| NKF- KDOQI (2015)25 | The decision to initiate maintenance dialysis in patients who choose to do so should be based primarily upon an assessment of signs and/or symptoms associated with uremia, evidence of protein-energy wasting, and the ability to safely manage metabolic abnormalities and/or volume overload with medical therapy rather than on a specific level of kidney function in the absence of such signs and symptoms. |

| Canadian Society of Nephrology (2014)26 | For adults (aged > 18 yr) with an eGFR of less than 15 mL/ min per 1.73 m2, we recommend an “intent-to-defer” over an “intent-to-start-early” approach for the initiation of chronic dialysis. With the intent-to-defer strategy, patients with an eGFR of less than 15 mL/ min per 1.73 m2 are monitored closely by a nephrologist, and dialysis is initiated with the first onset of a clinical indication or a decline in the eGFR to 6 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or less, whichever of these should occur first. Clinical indications for the initiation of dialysis include the following: symptoms of uremia, fluid overload, refractory hyperkalemia or acidemia, or other conditions or symptoms that are likely to be ameliorated by dialysis. In the absence of these factors, the eGFR should not serve as a sole criterion for the initiation of dialysis unless it is 6 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or less. |

| ERA- EDTA/ERBP Advisory Board (2011)40 | In patients with a GFR <15 mL/min/1.73m2, dialysis should be considered when there is one or more of the following: symptoms or signs of uremia, inability to control hydration status or blood pressure or a progressive deterioration in nutritional status. It should be taken into account that the majority of patients will be symptomatic and need to start dialysis with GFR in the range 9–6 mL/min/1.73m2. High-risk patients e.g. diabetics and those whose renal function is deteriorating more rapidly than eGFR 4 mL/min/year require particularly close supervision. Where close supervision is not feasible and in patients whose uremic symptoms may be difficult to detect, a planned start to dialysis while still asymptomatic may be preferred. Asymptomatic patients presenting with advanced CKD may benefit from a delay in starting dialysis in order to allow preparation, planning and permanent access creation rather than using temporary access. |

| KDIGO (2012)39 | We suggest that dialysis be initiated when one or more of the following are present: symptoms or signs attributable to kidney failure (serositis, acid-base or electrolyte abnormalities, pruritus); inability to control volume status or blood pressure; a progressive deterioration in nutritional status refractory to dietary intervention; or cognitive impairment. This often but not invariably occurs in the GFR range between 5 and 10 ml/min/1.73 m2. (2B) |

Similar to the current KDOQI guidelines, the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) initiative’s 2012 guideline on CKD evaluation and management also endorses an approach to the timing of initiation of renal replacement therapy that rests primarily on an assessment symptom or signs attributable to kidney disease (Table 1).39 Unlike KDOQI, the KDIGO guideline does mention a specific GFR range at which symptoms may be expected to develop (between 5 and 10 ml/min/1.73m2), but stops short of recommending that dialysis be initiated once patients reach that level of kidney function, irrespective of uremic symptom burden.

In 2011, the European Renal Association – European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) European Renal Best Practice Advisory Board (ERBP) published an updated position statement providing updated guidance on when to start dialysis, specifically in response to the published results from the IDEAL study (Table 1).40 The previous guideline had last been published in 2002, and included a specific stipulation that even in the absence of symptoms, dialysis should be started “before the GFR has fallen to 6 ml/min/1.73m2”.41 The 2011 update to this guideline specifically cautioned against basing decisions regarding dialysis initiation on GFR as estimated by the MDRD equation or as determined by the Cockcroft-Gault equation. Additionally, the previous emphasis on using a GFR of 6 ml/min/1.73m2 was substantially weakened, and this was done specifically in response to the IDEAL findings. Similar to the KDIGO guidelines, the ERBP identified a range at which most patients develop symptomatic uremia, though the range identified was slightly different (6–9ml/min/1.73m2). Also similar to KDIGO, the ERBP guideline avoids specific mention of a GFR at which dialysis should be initiated in the absence of symptoms.

In contrast to clinical practice guidelines released by NKF-KDOQI, KDIGO, and the ERA-EDTA, the Canadian Association of Nephrology’s 2014 clinical practice guideline for timing the initiation of chronic dialysis does identify an absolute threshold of eGFR at which point dialysis should be initiated in patients with advanced CKD, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms (Table 1).26 The Canadian guideline, which followed a systematic review of the available literature including an analysis of resource utilization and costs of alternative initiation strategies, specifically advocates an “intent-to-defer” strategy, and placed a high value on avoidance of dialysis-related treatment burden and reducing resource use. The lower threshold of eGFR for this “intent-to-defer” strategy was determined to be 6 ml/min/1.73m2 and was identified by consideration of the median eGFR targeted in the late-start arm in the IDEAL trial. The choice of this lower threshold was made based on expert opinion with the stated goal to reduce the risk of emergent dialysis.26

Taken together, this evolution of clinical practice guidelines focused on the timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis over the past 10 years shows a profound influence of the results of the IDEAL trial as well as those of observational studies suggesting benefit or even harm associated with initiation of dialysis at higher compared to lower levels of kidney function. Additionally, a clear trend towards a focus on symptom/sign assessment and shared decision-making among providers, patients, and caregivers is evident. Future evolution of clinical practice guidelines and recommendations will depend on investment in future research work to define the physiological and biological underpinnings of the uremic syndrome, identify which uremic signs and symptoms reliably improve with initiation of dialysis, and determine how assessment of uremic symptom burden can be systematically and effectively integrated into clinical encounters and discussions between providers and patients.

TRENDS IN THE TIMING OF DIALYSIS INITIATION SINCE IDEAL

From the mid-1990s through 2009, the mean eGFR in patients starting maintenance dialysis in the U.S. saw an inexorable yearly rise from 7.7 ml/min/1.73m2 in 1996 to 11.2 ml/min/1.73m2 in 2009.1 This irrefutable trend has been well described and discussed, and although definitive evidence of the etiology of this trend is lacking, some commentators have hypothesized that this finding may have been due to tacit acceptance of “conventional wisdoms” regarding the benefit of dialytic clearance that nonetheless were unjustified based on the available evidence.20,21,42 One additional potential cause of the trend toward higher eGFR at dialysis initiation over the 25 year period ending in 2009 is changes in the demographic makeup of the population reaching ESRD in the U.S. However, studies that have sought to account for demographic and clinical characteristics have shown that the trend was evident irrespective of these characteristics. O’Hare et al. analyzed data from the USRDS over a 10-year period to generate model-based estimates of the change in timing of dialysis initiation for individuals with ESRD in the U.S. and found that overall, incident patients started dialysis an average of 147 days earlier in 2007 compared to 1997, following adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics.43 This trend toward earlier initiation was even more pronounced in the elderly population, with patients over 75 years of age have started dialysis 233 days earlier in 2007 compared to 1997.

Another candidate contributor to the observed secular trend in eGFR at dialysis initiation is provider-level financial incentives due to favorable physician reimbursement of ESRD care relative to CKD care in the U.S. A logical comparison group to test this hypothesis is veterans receiving care within the Department of veterans Affairs (VA) system, where physicians are salaried and thus do not receive higher remuneration for patients on dialysis. Yu et al.44 compared trends in timing of dialysis initiation among veterans who initiate dialysis at a VA medical center with those who initiated dialysis outside the VA system. Although she found that the adjusted probability of starting dialysis at an eGFR of ≥10 ml/min/1.73m2 was lower for veterans who started dialysis within the VA, the temporal trends in eGFR at dialysis initiation were similar among the different groups, and were both consistent with a slow and steady increase in the mean eGFR at dialysis start over the study period (2000–2009). This finding suggested that although health system factors and reimbursement may influence dialysis-initiation practices to some extent, they are not the primary driver of secular trends in the timing of dialysis initiation.

Another potential contributor to changes in dialysis initiation practice patterns is dialysis provider and facility level factors. Over the past 15 years, automated reporting by laboratories of the eGFR calculated using a variety of creatinine-based estimating equations has been widely adopted around the world in efforts to raise awareness of kidney disease and in recognition of the limitations of interpretation of the serum creatinine in isolation.45,46 Two recently published studies have sought to determine whether such automated eGFR reporting has influenced nephrologist decision-making and practices regarding the timing of dialysis initiation. Brimble et al.47 surveyed 822 nephrologists in 4 countries including the U.S., and presented respondents with clinical vignettes of patients with advanced CKD approaching the need for renal replacement therapy that either included serum creatinine values plus the corresponding eGFR, or serum creatinine alone. Allocation to vignettes that included eGFR was randomly determined, and respondents were asked to rank the likelihood that he or she would recommend initiation of dialysis based on the clinical vignette. The major finding was that irrespective of level of serum creatinine, inclusion of the eGFR was associated with a modest but statistically significant increase in the probability that initiation of dialysis would be recommended. Sood et al.48 assessed the eGFR at dialysis initiation among 22,208 patients in 4 Canadian provinces from 2001 through 2010, a period which encompassed the implementation of automated eGFR laboratory reporting within these provinces. Using an interrupted time-series approach that employed multivariable regression models, the investigators did not find evidence in a change in the trajectory of eGFR at dialysis initiation before compared to after implementation of eGFR reporting. Reasons for the discrepant findings between these two studies may include a limitation of external generalizability of a survey-based study in which the response rate was less than 20%, the chance that response to clinical vignettes may not translate into real-life clinical decision-making, or actual differences in practice patterns. Other recent studies have assessed the association of provider and facility-level characteristics with the timing of dialysis initiation from 2001 to 2010. Using data from the USRDS, Slinin et al.49 analyzed nearly 84,000 patients in the U.S. who initiated dialysis in 2006 to determine whether provider characteristics and pre-ESRD care and vascular access were associated with eGFR at dialysis initiation. The findings of this study suggested that longer pre-dialysis nephrology care and presence of a permanent dialysis access were associated with a higher eGFR at the start of dialysis. Additionally, certain provider characteristics such as fewer years of nephrology practice experience were also associated with initiation of dialysis at higher levels of kidney function. In contrast, neither state-level variation in the availability of the nephrology workforce in the U.S. nor variation in practice patterns by geographic region or dialysis facility appear to be major contributors to observed trends in eGFR at dialysis initiation.50,51

One question that arises when considering secular trends in the timing of dialysis initiation over the past 15 years in the U.S. is whether there has been a systematic change in the clinical phenotype of patients with advanced kidney disease approaching the need for renal replacement therapy that may explain the rise in eGFR at dialysis initiation from the mid-1990s through 2009. Although studies that have sought to account for commonly collected demographic and clinical information have generally shown persistence of this upward trend in eGFR, it is possible that there has been a change in patient-level characteristics over time that are harder to capture in cohort and registry-based studies, such as frailty or physical functioning. Bao et al. assessed the association of self-reported measures of frailty with timing of dialysis initiation using data from the Comprehensive Dialysis Study, a special study of the USRDS, and found that frailty was independently associated with eGFR at dialysis initiation, although linear trends over time were not assessed. However, studies that have specifically looked at trends in the intensity of healthcare delivered around the time of dialysis initiation using Medicare claims data do not generally support a change in the clinical case-mix over time that may explain observed trends in eGFR at the start of maintenance dialysis.52 Similarly, O’Hare et al.53 recently reported the results of a study in which they examined the clinical presentation at the time of dialysis initiation among a sample of veterans who initiated dialysis within the VA system from 2000 to 2009. Using a detailed and comprehensive chart abstraction protocol, the investigators reviewed the charts of 1691 patients and found that the mean eGFR at dialysis initiation rose from 9.8 ml/min/1.73m2 in years 2000–2004 to 11.0 ml/min/1.73m2 in years 2005–2009. However, they also determined that the level of clinical acuity was similar between the two time periods, and furthermore the frequency of documented signs of symptoms consistent with the uremic syndrome was also similar during both time periods. In contrast, one report from Canada found that rates of withdrawal from dialysis after initiation doubled from 2001 and 2009, and such withdrawals were more common among elderly patients and those with higher eGFR at the time of initiation of dialysis.54 Results from this study and others suggest that perhaps a greater proportion of sicker patients initiated in the second half of the first decade of the twentieth century compared to the first half, and that these patients may have contributed to raising the average eGFR at the start of dialysis overall.

Whether the continuous upward trend of eGFR at dialysis initiation seen in the 1990s and early 2000s in the U.S. truly represented a liberalization of dialysis practices as some have suggested55, or whether more likely a combination of myriad contributors was responsible, what is clear is that 2010 marked a key inflection point (Figure 1). From 2009 to 2010, the mean eGFR at dialysis initiation in the U.S. did not rise, and instead stayed steady at 11.2 ml/min/1.73m2. Since 2010, this number has actually decreased slightly, and in 2013 (the last year for which data from the USRDS is currently available) was 10.3 ml/min/1.73m21 The percent of incident ESRD patients who began maintenance dialysis with eGFR ≥10 ml/min/1.73m2, which had previously risen from 13% in 1996 to 43% in 2010, fell slightly over the subsequent 3 year period to 40% in 2013.1 Similarly, the percentage of incident dialysis patients who initiated renal replacement therapy with eGFR <5 ml/min/1.73m2, which had previously fallen from nearly 34% in 1996 to 12% in 2010, rose for the first time in 2 decades to 14% in 2013.1

Figure 1. Mean eGFR at Initiation of Dialysis Among Incident End-Stage Renal Disease Cases in the United States, 1996–2013.

Adapted from: United States Renal Data System Annual Data Reports from 2007, 2010, 2013, and 2015.

This changing pattern of eGFR at dialysis initiation from 2010 to 2013 marks a profound shift from the temporal and secular trends of the previous nearly two decades. The causes and contributors to this new plateau and even slight decline in eGFR are at this time unclear, but are likely many in number. Certainly the publication of the results from the IDEAL trial in 2010 and the subsequent widespread attention from both commentators in the medical literature and in the popular press have done much to emphasize the lack of clinical benefit with routine initiation of dialysis at higher levels of GFR. Additionally, the revision and publication of the most recent iterations of clinical practice guidelines from expert consortiums such as NKF-KDOQI and KDIGO have, as previously discussed, moved substantially away from recommending initiation of dialysis due solely to laboratory evidence of kidney function decline. Though not proven, it is likely that increasing acceptance of the recommendations presented in these guidelines, shaped in major part by the results of the IDEAL study, have influenced clinical decision-making among practicing nephrologists. Studies that have sought to survey nephrologists regarding clinical, social and logistical factors which most influence the decision of when to recommend starting renal replacement therapy in patients with advanced CKD have shown that prior to publication of the IDEAL study, the level of excretory kidney function was considered the most important factor in decision-making for uncomplicated patients in over half of all respondents.56 Unfortunately, there are no similar data available from the period following publication of the IDEAL study result and recent updated clinical practice guidelines. Whatever the underlying cause of the recent change in patterns, it is currently an unanswered question of whether or not the coming years will see the establishment of a new “steady state” for mean eGFR at the initiation of dialysis in the U.S. or whether instead we will witness a continued slow (or sharp) turn downward.

NON-eGFR-BASED APPROACHES TO DETERMINE TIMING OF DIALYSIS INITIATION

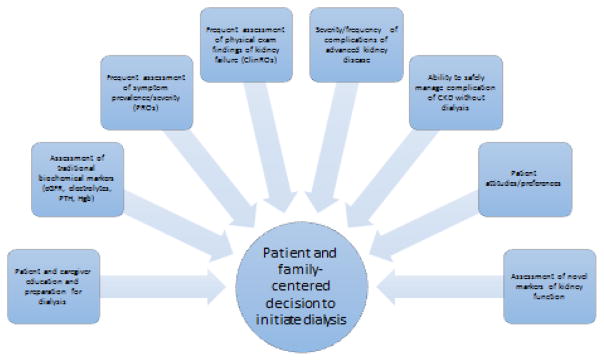

The results of the IDEAL study and the publication of clinical practice guidelines in the U.S. and abroad that have advocated a personalized approach to dialysis initiation decision making have been interpreted by many nephrologists as an endorsement that the determination of the optimal timing of dialysis initiation remains in the domain of the “art” – rather than the science – of medicine. There are, however, promising new areas of active inquiry in nephrology and health services research which may in the coming years provide additional guidance for this critically important decision for nephrologists and our patients. These areas include – but are of course not limited to – innovation in uremic symptom assessment, investigation of novel markers of kidney function including proximal tubular secretion, and an increased emphasis on the importance of patient-provider-caregiver shared decision-making. Ideally, advances in these areas may lead to future development of a new integrative approach to decision-making regarding the timing of dialysis initiation that will be patient-centered, individualized, and optimize outcomes that are important to patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Future Directions: A Hypothetical Integrative Patient-Centered Approach to Decision-Making Regarding Timing of Dialysis Initaition.

Abbreviations: PRO, patient-reported outcome; ClinRO, clinician-reported outcome.

Symptom assessment

Partially in response to the findings from the IDEAL study, and in the context of recommendations in current clinical practice guidelines governing the timing of dialysis initiation, there has been increasing focus within the nephrology research communicating on the importance of accurate assessment of signs and symptoms of the uremic syndrome in patients with advanced kidney disease as a critical component of the dialysis initiation decision-making process, and in particular on the importance of balancing the burden of symptoms attributable to CKD with the very real burden associated with dialysis therapy.57 However, as some have pointed out, there is a remarkable paucity of published data reporting on the character of symptoms at the time of development of ESRD and their subsequent course through the transition to maintenance dialysis and beyond.6,22,57 The burden of physical, emotional, and psychological symptoms among patients with advanced kidney disease approaching the need for renal replacement therapy is high, and results in low health-related quality of life.58,59 However, a number of studies published over the past decade have also shown that patients undergoing maintenance dialysis also suffer from a high burden of residual symptoms, in many cases with frequency and severity that are comparable to patients who have not yet started dialysis.60–62 Few studies have tracked the progression or symptom prevalence and severity among patients with advanced kidney disease who go on to initiate maintenance dialysis, and it remains unclear which symptoms among patients with advanced kidney disease reliably improve with the start of dialysis.63 Furthermore, uremic symptoms may be subtle, patients may adapt to a higher symptom burden or lower level of functioning, or providers may not elicit the full range of symptoms experienced by patients.64 New research investigating the integration of new technologies that allow patient-driven symptom assessment, such as smartphone-based mobile health apps, have shown promise in facilitating bidirectional communication between patients and providers, and may represent tools to allow incorporation of more granular data on patient symptom burden into clinical car pathways.65 Further research is needed to generate a detailed understanding of the longitudinal burden of uremic symptom severity and frequency in advanced CKD that may allow the development of a new clinical paradigm regarding the timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis that incorporates systematic patient-centered symptom assessment.

In the coming years, results from ongoing prospective studies may shed additional light on the role of symptom assessment and symptom burden in dialysis initiation decision making. The European Quality Study on Treatment in Advanced Kidney Disease (EQUAL) is an ongoing international prospective cohort study in CKD patients >65 years progressing toward the need for renal replacement therapy.66 Enrollment of 3500 patients from five countries (Germany, Italy, Sweden, The Netherlands, and the UK) is planned with the goal to investigate how uremic signs and symptom develop during the progression of advanced CKD, and how such signs and symptoms may predict outcomes around and following dialysis initiation. The study is also collecting data on health-related quality of life, nephrologist decision-making, and patient preferences and health-care related satisfaction. Studies such as EQUAL will generate novel prospective and granular data on symptoms in patient with advanced kidney disease, and will hopefully provide a clinically useful evidence-base for the integration of symptom assessment into clinical decision-making.

Uremic solute assessment

The results of the IDEAL study have challenged the paradigm of using GFR as a primary guide for the timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis. This recognition has prompted a search for new biological markers reliably associated with outcomes around the time of dialysis initiation, including improvement in symptom burden and health-related quality of life, that if identified could potentially be integrated into a new clinical paradigm for dialysis initiation decision-making.

One group of candidate biological markers that could potentially inform dialysis decision-making includes protein-bound solutes (uremic retention solutes) produced by intestinal microbial flora. This large group of solutes, which includes indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl sulfate, and hippurate, are normally secreted by kidney proximal tubular cells, accumulate with loss of kidney function, and have been associated with progression of CKD and adverse cardiovascular mortality.67–69 Both indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate have been associated with elevated levels of inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, which in turn are linked definitively with fatigue, uremic pruritis, anorexia, and other component symptoms of the uremic syndrome.70–73 Additionally, gastrointestinal adsorption and removal of these protein-bound uremic toxins through use of orally administered adsorbents has been shown to potentially improve uremic symptoms, in particular malaise, in a dose-dependent fashion.74,75 However, there remains a critical paucity of data linking specific uremic toxins to changes in kidney disease-associated symptoms with initiation or adaptation to maintenance dialysis. Future research to identify if such a linkage may exist could suggest additional biological markers to potential integrate into a new clinical paradigm for dialysis decision-making.

Shared decision-making

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its landmark report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. In this report, the IOM laid out its vision for a strategy and action plan for building a stronger health system through addressing specific key domains. One of the key domains identified for all health care organizations to pursue was for care to be patient-centered, including care that is responsive to and guided by individual patient needs and values. In nephrology, this charge has been reflected in a growing emphasis on shared decision-making among patients, provider, and caregivers in major health-care decisions including if and when to start dialysis.76 Unfortunately, until the past few years, there has been a paucity of data on how such complex decisions are actually made in practice. A recent qualitative study by Wong et al.77 sought to identify central themes related to the timing of dialysis initiation by performing qualitative analysis of the medical records of nearly 1700 patients starting dialysis within the VA system from 2000 to 2009. This analysis by Wong and colleagues revealed the extraordinary complexity and many inputs to the decision by providers, patients, and their families to start dialysis, and a decision shaped by the interplay of multiple interrelated processes including the specific care practices of individual physicians, perceived momentum toward ESRD, and complex patient-physician dynamics. In particular, the investigators found that decision regarding timing of dialysis initiation often revealed underlying tensions and differences between physician priorities and patient/caregiver goals and preferences. Studies such as this one emphasize the challenges in implementing focused clinical practice guidelines in actual clinical practice and highlight the need for a greater understanding of how to tailor and target interventions such as the initiation of maintenance dialysis to the needs of each individual patient.

CONCLUSIONS

How should we integrate the landmark results from the IDEAL study with the subsequent research findings and clinical practice guidelines that have followed, along with the substantial number of unanswered questions regarding the optimal timing for dialysis initiation that still remain? First, it is clear that using eGFR as the primary guide for when to start dialysis in a patient with progressive advanced CKD is a strategy that should likely be abandoned. Second, dialysis initiation decision-making should be done using a patient-centered approach in which symptom assessment and patient-level goal ascertainment is central. Third, a reasonable approach is to defer initiation of dialysis in asymptomatic individuals until the development of signs or symptoms consistent with the uremic syndrome that may reasonably be expected to improve with dialysis treatment. Deferred initiation does not, however, mean deferred preparation, and early discussions regarding medical and psychosocial preparation for the initiation of dialysis should not be delayed. This includes discussion and education regarding placement of dialysis access, dialysis modality selection, advance care planning, involvement of caregivers in transportation (for in-center hemodialysis) or providing assistance with home therapies (for peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis).

A necessary precondition for the approach we have outlined, however, is that frequent visits with the patient and his or her caregivers must occur for the purpose of assessment of signs of symptoms of uremia, and also to discuss how burden of such signs and symptoms may compare to the burden to be expected with initiation of maintenance dialysis. These visits should be conducted in concordance with the principles of shared decision making, and should be patient-centered and inclusive. Alternative approaches including conservative management and incremental dialysis should be considered for some patients, as should efforts to preserve residual kidney function no matter the plan for renal replacement therapy. Reassessment of patients’ priorities and goals for their overall health care and for dialysis treatment should be continually reassessed, in the period approaching – as well as the period following - initiation of dialysis.

There is a critical need for the nephrology research community to pursue work to better understand and define the components of the uremic syndrome, identify their biological and physiological underpinnings, determine which symptoms and signs may reliably improve with the initiation of dialysis, and how such changes may vary by important patient subgroups defined by both demographic and clinical variables. Such work may eventually identify new therapeutic targets or new dialysis-based (or non-dialysis-based) therapeutic strategies to manage uremia and its complications. Importantly, the results of ongoing observational studies such as the EQUAL will in the future provide novel and important granular information on the development and progression of uremic symptoms in late stage CKD and how patient preferences regarding treatment may influence the timing and process of dialysis initiation.66 In the meantime, we must integrate results from the IDEAL study and the studies that have followed with recent trends in clinical practice and clinical outcomes to maintain a patient-centered approach to dialysis initiation decision-making. Ultimately, what is needed is a new individualized clinical paradigm that integrates assessment of existing and potential novel biochemical markers – beyond serum creatinine and eGFR – with systematic clinical assessment of uremic signs and symptoms that may ultimately lead to optimizing patient-centered clinical outcomes for patients with ESRD approaching the need for maintenance dialysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH/NCATS grant KL2 TR000421 to the University of Washington Institute for Translational Health Sciences. Some data in this article have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2015 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peer Kidney Care Initiative 2014 Report: Dialysis Care and Outcomes in the United States - Chapter 2: Hospitalization. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:S35–S92. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan KE, Maddux FW, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Karumanchi SA, Thadhani R, Hakim RM. Early Outcomes among Those Initiating Chronic Dialysis in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2642–2649. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03680411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saggi SJ, Allon M, Bernardini J, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Shaffer R, Mehrotra R. Considerations in the optimal preparation of patients for dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:381–389. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehrotra R, Rivara M, Himmelfarb J. Initiation of dialysis should be timely: neither early nor late. Semin Dial. 2013;26:644–649. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivara MB, Mehrotra R. Is early initiation of dialysis harmful? Semin Dial. 2014;27:250–252. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McIntyre CW, Rosansky SJ. Starting dialysis is dangerous: how do we balance the risk? Kidney Int. 2012;82:382–387. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan SS, Xue JL, Kazmi WH, Gilbertson DT, Obrador GT, Pereira BJG, et al. Does predialysis nephrology care influence patient survival after initiation of dialysis? Kidney Int. 2005;67:1038–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singhal R, Hux JE, Alibhai SMH, Oliver MJ. Inadequate predialysis care and mortality after initiation of renal replacement therapy. Kidney Int. 2014;86:399–406. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosansky SJ, Clark WF, Eggers P, Glassock RJ. Initiation of dialysis at higher GFRs: is the apparent rising tide of early dialysis harmful or helpful? Kidney Int. 2009;76:257–261. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Susantitaphong P, Altamimi S, Ashkar M, Balk EM, Stel VS, Wright S, et al. GFR at Initiation of Dialysis and Mortality in CKD: A Meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:829–840. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churchill DN. An evidence-based approach to earlier initiation of dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 1997;30:899–906. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grootendorst DC, Michels WM, Richardson JD, Jager KJ, Boeschoten EW, Dekker FW, et al. The MDRD formula does not reflect GFR in ESRD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1932–1937. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins JF, Craig JC, Fraenkel MB, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:609–619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins JF, Craig JC, Dempster J, et al. The Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study: study rationale and design. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24:176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris A, Cooper BA, Li JJ, Bulfone L, Branley P, Collins JF, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Initiating Dialysis Early: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:707–715. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson DW, Wong MG, Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins JF, et al. Effect of Timing of Dialysis Commencement on Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Planned Initiation of Peritoneal Dialysis in the Ideal Trial. Perit Dial Int. 2012;32:595–604. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2012.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whalley GA, Marwick TH, Doughty RN, Cooper BA, Johnson DW, Pilmore A, et al. Effect of early initiation of dialysis on cardiac structure and function: results from the echo substudy of the IDEAL trial. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2013;61:262–270. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lameire N, Van Biesen W. The Initiation of Renal-Replacement Therapy — Just-in-Time Delivery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:678–680. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1006669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosansky S, Glassock RJ, Clark WF. Early Start of Dialysis: A Critical Review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1222–1228. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09301010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosansky SJ, Cancarini G, Clark WF, Eggers P, Germaine M, Glassock R, et al. Dialysis initiation: What’s the rush? Semin Dial. 2013;26:650–657. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abra G, Tamura MK. Timing of initiation of dialysis: time for a new direction? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:329–333. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328351c244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streja E, Nicholas SB, Norris KC. Controversies in Timing of Dialysis Initiation and the Role of Race and Demographics. Semin Dial. 2013:26. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollock CA, Cooper BA, Harris DC. When should we commence dialysis? The story of a lingering problem and today’s scene after the IDEAL study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2162–2166. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daugirdas JT, Depner TA, Inrig J, Mehrotra R, Rocco MV, Suri RS, et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Hemodialysis Adequacy: 2015 Update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:884–930. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nesrallah GE, Mustafa RA, Clark WF, Bass A, Barnieh L, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Canadian Society of Nephrology 2014 clinical practice guideline for timing the initiation of chronic dialysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186:112–117. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright S, Klausner D, Baird B, Williams ME, Steinman T, Tang H, et al. Timing of Dialysis Initiation and Survival in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1828–1835. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06230909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosansky SJ, Eggers P, Jackson K, Glassock R, Clark WF. Early start of hemodialysis may be harmful. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:396–403. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crews DC, Scialla JJ, Liu J, Guo H, Bandeen-Roche K, Ephraim PL, et al. Predialysis Health, Dialysis Timing, and Outcomes among Older United States Adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:370–379. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J, An JN, Hwang JH, Kim Y-L, Kang S-W, Yang CW, et al. Effect of dialysis initiation timing on clinical outcomes: a propensity-matched analysis of a prospective cohort study in Korea. PloS One. 2014;9:e105532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernán MA, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 2000;11:561–570. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjölander A, Nyrén O, Bellocco R, Evans M. Comparing different strategies for timing of dialysis initiation through inverse probability weighting. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1204–1210. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crews DC, Scialla JJ, Boulware LE, Navaneethan SD, Nally JV, Jr, Liu X, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Early Versus Conventional Timing of Dialysis Initiation in Advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:806–815. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HW, Kim S-H, Kim YO, Jin DC, Song HC, Choi EJ, et al. The Impact of Timing of Dialysis Initiation on Mortality in Patients with Peritoneal Dialysis. Perit Dial Int J Int Soc Perit Dial. 2015;35:703–711. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2013.00328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nacak H, Bolignano D, Diepen MV, Dekker F, Biesen WV. Timing of start of dialysis in diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic literature review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:306–316. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hemodialysis Adequacy, Update 2006. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:S2–S90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slinin Y, Greer N, Ishani A, MacDonald R, Olson C, Rutks I, et al. Timing of dialysis initiation, duration and frequency of hemodialysis sessions, and membrane flux: a systematic review for a KDOQI clinical practice guideline. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2015;66:823–836. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tattersall J, Dekker F, Heimbürger O, Jager KJ, Lameire N, Lindley E, et al. When to start dialysis: updated guidance following publication of the Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2082–2086. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.European Best Practice Guidelines Expert Group on Hemodialysis, European Renal Association. Measurement of renal function, when to refer and when to start dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc. 2002;17(Suppl 7):7–15. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_7.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosansky SJ. The sad truth about early initiation of dialysis in elderly patients. JAMA. 2012;307:1919–1920. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Boscardin WJ, Clinton WL, Zawadzki I, Hebert PL, et al. Trends in timing of initiation of chronic dialysis in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1663–1669. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu MK, O’Hare AM, Batten A, Sulc CA, Neely EL, Liu C-F, et al. Trends in Timing of Dialysis Initiation within Versus Outside the Department of Veterans Affairs. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1418–1427. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12731214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jain AK, McLeod I, Huo C, Cuerden MS, Akbari A, Tonelli M, et al. When laboratories report estimated glomerular filtration rates in addition to serum creatinines, nephrology consults increase. Kidney Int. 2009;76:318–323. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Accetta NA, Gladstone EH, DiSogra C, Wright EC, Briggs M, Narva AS. Prevalence of estimated GFR reporting among US clinical laboratories. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2008;52:778–787. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brimble KS, Mehrotra R, Tonelli M, Hawley CM, Castledine C, McDonald SP, et al. Estimated GFR Reporting Influences Recommendations for Dialysis Initiation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sood MM, Komenda P, Rigatto C, Hiebert B, Tangri N. The Association of eGFR Reporting with the Timing of Dialysis Initiation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2097–2104. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013090953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slinin Y, Guo H, Li S, Liu J, Morgan B, Ensrud K, et al. Provider and Care Characteristics Associated with Timing of Dialysis Initiation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:310–317. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04190413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ku E, Johansen KL, Portale AA, Grimes B, Hsu C. State level variations in nephrology workforce and timing and incidence of dialysis in the United States among children and adults: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2015:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-16-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sood MM, Manns B, Dart A, Hiebert B, Kappel J, Komenda P, et al. Variation in the Level of eGFR at Dialysis Initiation across Dialysis Facilities and Geographic Regions. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:1747–1756. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12321213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong SPY, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM. Healthcare Intensity at Initiation of Chronic Dialysis among Older Adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:143–149. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Hare AM, Wong SP, Yu MK, Wynar B, Perkins M, Liu C-F, et al. Trends in the Timing and Clinical Context of Maintenance Dialysis Initiation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1975–1981. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ellwood AD, Jassal SV, Suri RS, Clark WF, Na Y, Moist LM. Early Dialysis Initiation and Rates and Timing of Withdrawal From Dialysis in Canada. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:265–270. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Hare AM, Vig EK, Hebert PL. Initiation of Dialysis at Higher Levels of Estimated GFR and Subsequent Withdrawal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:179–181. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12841212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van de Luijtgaarden MWM, Noordzij M, Tomson C, Couchoud C, Cancarini G, Ansell D, et al. Factors Influencing the Decision to Start Renal Replacement Therapy: Results of a Survey Among European Nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:940–948. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johansen KL. TIme to rethink the timing of dialysis initiation. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:382–383. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1057–1064. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00430109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rivara MB, Chen CH, Nair A, Cobb D, Himmelfarb J, Mehrotra R. Indication for Dialysis Initiation and Mortality in Patients with Chronic Kidney Failure: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.06.024. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Rotondi AJ, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, et al. Development of a symptom assessment instrument for chronic hemodialysis patients: the dialysis symptom index. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:226–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA, et al. Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2487–2494. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005020157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weisbord SD. Symptoms and their correlates in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:319–327. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rivara MB, Robinson-Cohen C, Kestenbaum B, Roshanravan B, Chen CH, Himmelfarb J, et al. Changes in symptom burden and physical performance with initiation of dialysis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Hemodial Int. 2015;19:147–150. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Unruh ML, Palevsky PM, et al. Renal Provider Recognition of Symptoms in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:960–967. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00990207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ong SW, Jassal SV, Miller JA, Porter EC, Cafazzo JA, Seto E, et al. Integrating a Smartphone Based Self Management System into Usual Care of Advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1054–1062. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10681015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jager KJ, Ocak G, Drechsler C, Caskey FJ, Evans M, Postorino M, et al. The EQUAL study: a European study in chronic kidney disease stage 4 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012:gfs277. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meijers BKI, Claes K, Bammens B, de Loor H, Viaene L, Verbeke K, et al. p-Cresol and cardiovascular risk in mild-to-moderate kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1182–1189. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07971109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bammens B, Evenepoel P, Keuleers H, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y. Free serum concentrations of the protein-bound retention solute p-cresol predict mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1081–1087. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hsu H-J, Yen C-H, Chen C-K, Wu I-W, Lee C-C, Sun C-Y, et al. Association between uremic toxins and depression in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bossola M, Di Stasio E, Giungi S, Rosa F, Tazza L. Fatigue is associated with serum interleukin-6 levels and symptoms of depression in patients on chronic hemodialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bossola M, Ciciarelli C, Di Stasio E, Conte GL, Vulpio C, Luciani G, et al. Correlates of symptoms of depression and anxiety in chronic hemodialysis patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kimmel M, Alscher DM, Dunst R, Braun N, Machleidt C, Kiefer T, et al. The role of micro-inflammation in the pathogenesis of uraemic pruritus in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:749–755. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rossi M, Campbell KL, Johnson DW, Stanton T, Vesey DA, Coombes JS, et al. Protein-bound uremic toxins, inflammation and oxidative stress: a cross-sectional study in stage 3–4 chronic kidney disease. Arch Med Res. 2014;45:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schulman G, Agarwal R, Acharya M, Berl T, Blumenthal S, Kopyt N. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of AST-120 (Kremezin) in patients with moderate to severe CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:565–577. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Akizawa T, Koide K, Koshiwaka S. Effects of Kremezin on patients with chronic renal failure: Results of a nationwide clinical study. Kidney Dial. 1998;45:373–388. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moss AH. Revised Dialysis Clinical Practice Guideline Promotes More Informed Decision-Making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2380–2383. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07170810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wong SY, Vig EK, Taylor JS, et al. Timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis: A qualitative analysis of the electronic medical records of a national cohort of patients from the department of veterans affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:228–235. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]