Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic life-limiting disorder characterised by persistent airflow obstruction and progressive breathlessness. Discussions/conversations between patients and clinicians ensure palliative care plans are grounded in patients' preferences. This systematic review aimed to explore what is known about palliative care conversations between clinicians and COPD patients.

A comprehensive search of all major healthcare-related databases and websites was performed following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Studies were quality assessed, employing widely used quality-assessment tools, with only papers scoring moderate-to-high quality included. All relevant data were extracted. A narrative synthesis was used to analyse, process and present the final data.

The findings indicated that the frequency and quality of palliative care conversations is generally poor. Patients and physicians identified many barriers and important topics were not discussed. Patients and clinicians reported tension between remaining hopeful and the reality of the patients' condition. When discussions did happen, they often occurred at an advanced stage of illness and in respiratory wards and intensive care units.

In conclusion, current care practices do not facilitate satisfactory conversations about palliative care between COPD patients and clinicians. This impacts upon the fulfilment of patients' preferences at the end of life.

Short abstract

Conversations about palliative care in COPD http://ow.ly/NlKt307jgRs

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterised as a chronic disorder with persistent airflow obstruction, progressive breathlessness and chronic productive cough [1, 2]. COPD is associated with anxiety, depression, lack of energy, anorexia and restricted mobility [3–6]. In the UK, it is estimated that 3 million people have COPD [7, 8] and it is responsible for 30 000 deaths per annum [9].

People suffering from life-threatening illnesses, such as advanced COPD, should receive palliative care in order to improve their own and their families' quality of life [10, 11]. Palliative care focuses on the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of all physical, psychosocial and spiritual issues affecting the patient and their relatives [10, 11]. Any palliative care provided within the last 12 months of life is considered as end-of-life care, the last phase of palliative care [12].

The NHS End of Life Care strategy recommends open conversations between healthcare professionals and patients as the end of life approaches [9, 13]. These discussions are the first step in ensuring that well-planned care is delivered [14]. Indeed, awareness that death is approaching and what can be expected is seen as a prerequisite of a “good death” [5].

Difficult prognostication in COPD and in identifying with confidence the patients who are likely to die within 6 months poses an important barrier for early palliative care delivery [15]. Despite the development of different prognostic tools, the uncertainty regarding the start of palliative care for COPD patients remains challenging [15]. Gore et al. [16] found in 2000 that patients with end-stage COPD suffer from multiple severe symptoms, such as breathlessness, anxiety and depression; only a small proportion of patients receive palliative care and social support; and patients are likely to die whilst on aggressive treatments and in intensive care unit settings. Considering this and acknowledging the difficulties in prognosticating, it remains the physician's responsibility to educate patients about palliative care and to understand and respect their preferences [15]. Professionals should consider patients' opinions and preferences when developing treatment escalation plans, emergency and resuscitation decisions, palliative care interventions and hospice care [15]. Preferences can only be understood, debated and agreed in early conversations with COPD patients [15].

Despite sharing similar health status, care trajectories and symptom burden [16, 17], the quality and the proportion of patients with COPD who receive palliative care compares poorly to the care received by patients with cancer [18–21]. Patients with COPD receive less palliative care and die following more aggressive treatments at the end of life than patients with lung cancer, despite having the same preferences for palliative care [22]. Although this suggests inequality in care provision based on diagnosis, it presents an opportunity to learn from practices in cancer care.

Given the importance of communication about palliative care between COPD patients and healthcare professionals, it was sought to systematically review the literature on palliative and end-of-life care discussions between healthcare professionals and patients with COPD in order to identify best practice, as well as the barriers, facilitators, challenges and meaning of these conversations.

Previous narrative and systematic reviews have been published in this subject [5, 15, 21–26]. However, a comprehensive, evidence-based and systematic review was thought to be necessary to contextualise newly developed research. Considering the limitations of previous reviews, a systematic literature review was developed. This review offers evidence gathered from virtually all relevant health-related databases and websites, presents evidence developed from 1996 to 2015 and places equal importance on all types of literature, includes only papers with moderate-to-high quality and systematically analyses the data gathered from all papers. Furthermore, this review highlights new information which previous reviews did not provide. The new topics consist of the following: place, frequency, quality, importance and disease features that triggered palliative care communication; in-depth information about barriers and facilitators; comparison of communication in COPD and cancer; and, finally, approaches to improve communication about palliative care in COPD. Healthcare professionals looking after COPD patients and researchers developing studies within this subject can use this review as an accurate reference for their day-to-day clinical practice.

Methods and analysis

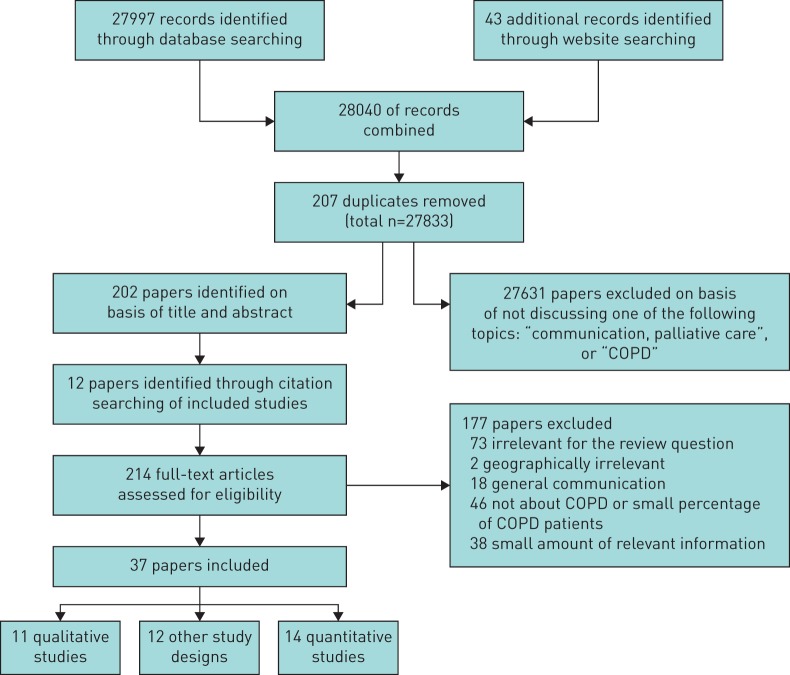

Prior to the development of the systematic literature review, a literature review protocol was outlined. Therefore, only a brief description of the protocol will be presented here. This review was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Guidelines, and was based in the systematic reviews included in this review [5, 23, 27, 28]. In order to find a comprehensive number of studies all major healthcare-related databases and websites were included (see table 1). The search strategy included search terms and medical subject headings (Supplement 1). The last search was conducted on the February 2, 2016. The reference list of every included paper was scanned to identify further papers of interest (figure 1) [18, 27]. The inclusion criteria are presented in table 2. As part of the inclusion criteria, a topic list to objectively search papers was outlined. This list resulted from a preliminary search of the literature and the inclusion of these topics was agreed by all authors. The topics outlined represent what a palliative care discussion should include. One of the topics was “What is the patient's and healthcare professional's understanding of palliative care?”. This topic focuses on what COPD patients think of palliative care, future treatments, approaching the end of life and of the impact of COPD in their future. This is one of the most relevant aspects and barriers when discussing palliative care with COPD patients [5, 29, 30].

TABLE 1.

Databases and websites searched

| Databases searched | Medline; CINAHL; PsycINFO; HMIC; AMED; Web of Science; ASSIA; IBSS; Delphis; PubMed; ScienceDirect; Cochrane Library; EMBASE; BNI; AgeInfo and Scopus. |

| Websites | Thorax Website; British Thoracic Society (BTS); National Institute For Health And Care Excellence (NICE); Medical Research Council (MRC); Department Of Health (DoH); Economic And Social Research Council (ESRC); National Institute For Health Research (NIHR); American Thoracic Association (ATS); British Lung Foundation (BLS); The National Council For Palliative Care (NCPC); The European Association For Palliative Care (EAPC); Association For Palliative Medicine (APM). |

FIGURE 1.

Literature search flow diagram.

TABLE 2.

Inclusion criteria of papers selected for review

| Paper language | Papers were included if written in English. The first language of all authors is English, therefore the inclusion of papers written in any other language would pose a barrier to thoroughly analyse the papers. |

| Participants | Participants included were people with COPD and healthcare professionals aged above 18 years old. COPD diagnosis should be done according with GOLD, in which a spirometry is performed showing a FEV1/FVC lower than 70%. Papers were included if the sample represented 50% or more of patients with COPD, except if the papers were purposely comparing COPD with other diseases. Papers had to include approximately the same amount of COPD patients and patients with other conditions. A 10% margin was used to include or exclude papers. However, the 10% margin was only applied to the larger categories of patients with other diseases. |

| Study design | All study designs were included in the review. The main purpose of the review was to identify and analyse all data published regarding this subject. Therefore, all study designs were included. |

| Study quality | Papers were included if presented high or moderate quality. The inclusion of papers with low quality would contaminate the overall findings and conclusion of the review, leading to inaccurate and unreliable data. |

| Country restriction | Only papers from North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand were included. This is thought relevant as literature from countries with different cultural believes towards health and from countries with small healthcare resources would not provide relevant and usable data for a European and North American society. |

| Information presented in papers | Papers were included if more than 50% of the information included was about palliative care conversations with COPD patients. This was done using word count. The papers excluded using this approach contained 30% or less of relevant information. Furthermore, the information contained in these papers did not present new information about the topic discussed. |

| Intervention | Conversations included were conversations about the topic “palliative care” between a person with COPD and a healthcare professional. |

| Discussion topics | Palliative care discussions addressed at least one of the following topics:

|

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity.

The selection process was completed by the main author and validated by the co-authors. Papers were selected, at first, by their title, secondly, by assessing their abstract, and finally, by analysing the whole article. The papers included in the review were screened by all authors and papers that raised uncertainty regarding criteria for inclusion were assessed, discussed and included/rejected by all authors. Therefore, actions to limit the impact of having one researcher screening the databases were adopted. These actions included: a very objective search strategy outlined in the literature review protocol; all authors reviewed and agreed on the inclusion of all papers and on the exclusion of papers that raised some uncertainty, and lastly, the reference list of all the papers included and of excluded papers about palliative care in COPD was thoroughly screened.

All papers were quality assessed using widely used appraisal tools. Qualitative papers were assessed using the tool: Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies, whilst quantitative papers were assessed using the form: Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [27, 31, 32]. At the end of each assessment using these two tools, a formal quality score was given to each paper according with the score obtained in each section. Based on this assessment, papers were scored as strong, moderate or weak quality, only papers with moderate or strong/high quality were included (figure 1). The rationale behind this was to increase reliability and validity of the findings of the review.

Data was extracted onto a data extraction form [27, 33]. To ensure validity and reliability, quality assessment and data extraction was completed by the main researcher, and 15% of all papers were assessed by all researchers. Given the diverse nature of the included studies, data analysis and synthesis were carried out using a narrative synthesis approach [34]. All researchers discussed and reached a consensus regarding the themes.

Results

The initial search retrieved 28 040 papers, after which all papers were scanned for eligibility criteria. Papers were excluded if not addressing the review's subject, if geographically irrelevant, if included a small percentage of COPD patients and/or if shown a small proportion of relevant information (refer to figure 1 for more information). However, no papers were excluded based on the quality assessment as being of poor quality. The total number of papers included in this review was 37 (see Supplement 2). 14 were quantitative studies, 11 were qualitative studies and 12 were diverse including narrative and systematic reviews, and comparative studies. The majority of papers were originated from the USA (n=20), seven from the UK, four were from other European countries, and the remaining six were from other countries.

Most papers studied patients aged above 65 years old, with severe to very severe airflow obstruction, who were oxygen dependent, previous exacerbations of COPD and an estimated prognosis of death of >1 year. When healthcare professionals were included in the studies, they were usually respiratory physicians. Outpatient clinics were the most common setting where conversations were studied. The majority of the papers generated from the USA (a total of 14 out of 20) were from the geographic area of Seattle, WA. Finally, some of these studies used the same sample, but processed the data in different forms and/or developed cross-sectional studies with the same participants.

Quantitative methods were most frequently employed and a lack of good quality in-depth qualitative research was noted. This was especially noted in the following themes: barriers for palliative care conversations, time, place and person to hold discussions, quality of communication and importance and impact of conversations.

Quality of evidence

All papers included in this review were quality assessed as described earlier. 58% of the qualitative papers included in the review were rated as high quality, whilst 42% were rated as being of moderate quality. The reasons for which papers were scored with moderate quality included: lack of comprehensive information regarding the methods chosen, recruitment process, exclusion and inclusion criteria; language used during interviews, the use of somehow leading questions was noted; and lack of discussion or limitations section. Quantitative papers had their quality evenly distributed, 47% of papers were rated as high quality, whilst 53% of papers showed moderate quality. Some reasons for rating papers with moderate quality were: the small percentage of participants that agreed to be included in the study; lack of representativeness of the sample chosen; and lack of control for cofounders. For more information regarding the specific weak and strong points of each paper, please refer to Supplement 2.

Frequency of discussions

One reason why COPD patients receive poor quality palliative care is that patient–physician communication about this is unlikely to occur [21]. 17 out of 37 papers highlighted that a variable percentage of COPD patients had discussed palliative care topics, this ranged from 0% to 56%, [5, 19, 21, 24, 25, 29, 30, 35–44]. Within this group, the majority (n=9), reported rates of discussion ⩽30% of patients [19, 29, 30, 35–39, 43]. This information was generated from papers including qualitative and quantitative studies with moderate and high quality, papers which compared COPD patients and patients with other diseases and narrative reviews. Patients, who reported having had a palliative care discussion in the past, had a worse overall health status than patients who did not have a discussion [19].

In a primary care study, 41% of general practitioners reported that they discussed prognosis often or always with their patients, while 15% reported discussing the subject rarely or never [40]. Moreover, 30% of general practitioners left it for patients or their relatives to raise the subject [40].

The desire to discuss palliative care topics was reported by more than half of the patients [19, 36]. This desire was acknowledged by half of general practitioners, who stated that some patients who would like to discuss prognosis did not get the opportunity [40]. Despite this, almost three-quarters of patients thought that their doctor probably or definitely knew the type of care they would want if they were too sick to speak for themselves [37]. In contrast, approximately 33% of patients stated that they did not wish to discuss palliative care with a healthcare professional [19, 36]. When comparing general practitioners from Auckland (Australia) and London (UK), Auckland-based general practitioners reported they discussed prognosis more often with severe COPD patients [45]. Interestingly, two-thirds of both groups agreed that they were more likely to discuss prognosis with cancer than COPD patients [45]. Furthermore, Dutch patients reported having these conversations significantly less frequently (12.3% in the Netherlands versus 17.6% in the USA) and with less quality than USA patients, despite the fact that Dutch patients had worse disease severity [46].

Time, place and person to discuss palliative care

Conversations about treatment preferences were reported to occur when the patient's COPD was advanced or when a serious decline was noted [3, 25, 44, 47]. Furthermore, the majority of physicians chose to initiate conversations when the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was <30% [3, 47]. In contrast, all respiratory physicians agreed that this should ideally be initiated when a patient was in a stable condition; however, patients' individuality and differing rates of disease progression added to the difficulty in timing the conversation [3]. The right time to discuss these topics was more defined in cancer than in COPD, where clinical specialist nurses (CNSs), specialising in cancer, were involved from diagnosis until the patient's deterioration [18, 22]. These CNSs provided personalised holistic care to cancer patients from the breaking of bad news, through their clinical treatment until the inevitable deterioration [18].

The disease features that most commonly triggered palliative care discussions according with clinicians were: FEV1 <30% of the predicted value; on or prior to an intensive care unit admission; when a sudden event had happened, such as the introduction of long-term oxygen and/or noninvasive ventilation; when maximum therapy was achieved; and when all curative treatments were exhausted [3, 25, 44, 47]. These features were chosen by clinicians because these mark an important point in the deterioration of the overall health status of the patient [3, 25, 44, 47].

When considering the place of conversations, two reviews and a small qualitative study reported that respiratory physicians thought discussions occurred more often in hospital wards and intensive care units than in outpatient clinics [22, 25, 47]. Furthermore, this study reported that only 23% of all palliative care conversations occurred during outpatients' clinics, when compared with 77% in intensive care units and respiratory wards [47]. Hospital admissions for COPD exacerbations were considered chaotic experiences and were not seen as an appropriate place to discuss palliative care [38].

A small qualitative study conducted in secondary care, reported that patients desire someone they knew and who knew them when discussing palliative care [38]. This usually translated to their general practitioner, whereas a respiratory physician or a specialist nurse was seen as someone with the clinical knowledge, but not necessarily the personal relationship [38].

Quality of communication

Patients have identified communication as one of the most important skills of physicians in providing adequate end of life care [35]. However, the majority of studies that assessed the quality of end-of-life care communication, reported that COPD patients rated the quality as low [35, 36, 39, 46]. Only a single study showed that communication was perceived as satisfactory by patients [41]. Quality of communication appeared to remain poor as patients approached their end of lives, even after the use of interventions to improve the frequency and quality of these discussions [36, 39]. Interventional studies demonstrated potential for improvement the quality of conversations, but only in two domains: patients' feelings about deterioration and spiritual beliefs [36, 39].

The quality of end-of-life care communication was rated low, mainly because most end-of-life care topics were not discussed [39, 46, 48]. These topics included talking about spiritual and religious beliefs, what dying might be like and prognosis [39]. When discussed, however, the quality was rated moderate to good [39].

When comparing Dutch with US patients, both groups reported very low scores for quality of communication about end-of-life care; however, the Dutch group reported lower quality of general and end-of-life care communication (median score for Dutch patients was 0.0 (interquartile range 0.0–2.0) versus 1.4 for US patients (interquartile range 0.0–3.6)) [46]. The tool used was the Quality of Communication Questionnaire [48]. Rating of quality of communication varies from 0 (very worst quality) to 10 (very best quality).

Content of discussions

Patients and healthcare professionals reported tension between remaining hopeful and the reality of the patients' condition, as this could pose a barrier for conversations and have an emotional impact on them [18, 29]. When patients were asked how much information they wanted, the initial answer was “all information”; however, simply asking this was not adequately enough to elicit informational needs [49].

Some patients believed that frank prognostic information might negatively impact their hope and increase symptoms of anxiety and depression; therefore, some physicians purposely withheld information to avoid this [20, 25, 49], as this poses a barrier when discussing palliative care with patients [37]. However, while suggesting it may be harmful for other patients, none considered it harmful for themselves [29]. Finally, many patients expressed the importance of individualising the clinician's approach for hope and prognosis, and of longstanding relationships with physicians [49].

Interestingly, participants often reported the use of the terms “emphysema” and “respiratory insufficiency” by physicians, but very rarely used “COPD”; and patients used “asthma” and “allergy” to describe their disease [41]. In contrast, the word “death” was not used, but it was the implied alternative if the patient chose not to be intubated [3]. Patients and their families rated emotional support as one of the skills they most prized in physicians [50].

Several studies reported the most frequent and the least discussed topics during palliative care discussions, these are highlighted in table 3 [3, 15, 20, 21, 35, 39, 41, 44, 46–48, 51–53]. Overall, patient education about palliative care was ranked as one of the most important topics by patients with COPD [51]. This suggested that for patients with end-stage COPD, education was an especially important domain in which physicians may fall short [15, 42, 51]. The vast majority of patients did not recognise palliative care as an option for COPD and some did not understand the meaning of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and of noninvasive ventilation [42]. The most important educational area for end-stage COPD patients was the progressive and irreversible nature of COPD [51].

TABLE 3.

Topics discussed during palliative care conversations

| Rarely discussed topics | Frequent topics |

|

|

Barriers and facilitators

The identification and overcome of barriers for palliative care communication will thereby promote high-quality palliative care for COPD patients [37]. Most studies reported that patients with COPD and physicians identified several barriers and few facilitators when discussing palliative care. Table 4 contains the most commonly endorsed barriers and facilitators by patients and clinicians when discussing palliative care. The second column of the table describes the barriers and facilitators endorsed by patients whilst the third column describes the barriers and facilitators endorsed by clinicians. Moreover, patients who reported palliative care conversations identified fewer barriers and more facilitators than patients who did not have previous discussions [37].

TABLE 4.

Most common barriers and facilitators endorsed by patients and physicians

| Patients | Physicians | |

| Barriers |

|

|

| Facilitators |

|

|

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Importance of palliative care discussions in COPD and the comparison with cancer

It may be useful for physicians to know whether the conversation about end-of-life care can reflect on a patient's perceived quality of care and whether these conversations can lead to perceptions of worse overall health status [19]. The occurrence of discussions was associated with higher health status, and of a higher quality of dying and death [54]. Patients were also more likely to report having received the best possible care, to acknowledge that their provider knew the treatments they wanted and to state that their doctor provided a very good explanation of their breathing problems if they engaged in conversations [54]. The majority of general practitioners and hospital physicians reported that conversations about prognosis were essential in the management of severe COPD and that they had an important role in facilitating these discussions [40, 44, 45].

Several differences between patients with COPD and patients with cancer were found in the included papers. When comparing COPD and cancer patients with regards to open awareness to end-of-life issues, various differences were evident. For instance, open awareness of death and dying was the norm for cancer patients [18, 19, 22] and patients with cancer were more likely than patients with COPD to describe their diagnosis by name [53]. Furthermore, COPD patients were more likely to express little or no understanding of their illness or diagnosis and received less education about their condition [53]. In contrast, patients with cancer were more likely to introduce prognosis in conversations regarding their disease [53].

Improving palliative care communication

When patients asked their physicians that they would like to receive all available treatments, physicians often concluded that patients wished to try all imaginable treatments, regardless of their benefit and invasiveness [55]. However, researchers argue that the most appropriate response was to discuss the patient's underlying treatment values and non-medical concerns and to provide accurate information about the patient's illness, prognosis and possible outcomes of life-sustaining treatments [55].

In order to improve the quality and frequency of palliative care discussions, five studies reported the use of an intervention to facilitate conversations [36, 43, 52, 56, 57]. These interventions were widely accepted and considered meaningful by the majority of participants. The interventions tested in these studies included: the use of computer-based reminders by physicians to improve frequency of conversations and completion of advance directives; the use of a short retreat to provide training to medical residents about communication skills; the use of feedback forms containing information about patients' preferences for future care; the use of home sessions to provide care, education and discussions about advance care planning and palliative care; and finally, the use of a computer program to provide education and training regarding palliative care for patients, in order to facilitate conversations with their clinicians [36, 43, 52, 56, 57]. The studies used different approaches to improve palliative care communication and used patients and/or clinicians as the main targets.

Despite the fact that all interventions were designed to improve frequency and/or quality of communication, only a modest impact in improving the characteristics of palliative care communication was noted [36, 43, 52, 56, 57]. One of the reasons why these interventions may have had little impact was that the interventions may have made the patients feel uncomfortable [36].

Suggestions for improving palliative care communication

A series of recommendations for palliative care conversations with COPD patients resulted from the data analysis and synthesis of the papers included in the review. These suggestions may provide some help to clinicians when approaching patients with COPD. The different suggestions are as follows:

Conversations should be started early in the disease course or opportunities to start discussions should be identified [30]. This will help to build a therapeutic relationship with the patient [30]. These opportunities/triggers can be: the presence of cor pulmonale [22]; the need for ventilation in the previous year [22]; arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide >45 mmHg or FEV1 <30% [22]; recent hospital admission or consultation [26, 30, 39, 50]; oxygen dependency or weight loss [22]; observed deterioration in the patient's condition [22, 30, 39, 50]; age above 70 years [18, 22]; assessment of therapy options [30, 50].

Discussions should be prepared and include the implications of diagnosis and of possible outcomes of life-sustaining treatments [30, 50, 55]. The patient's understanding about their condition and desired informational needs should be sought [50]. The patient's relatives should be included in discussions, if the patient so desires [41, 49]. In agreement with this, clinicians should identify and acknowledge patient's preferences [18, 55].

The clinician should share their medical opinion and propose a philosophy and plan of treatment, considering the patient's needs and wishes [50, 55]. During this, patients may feel upset or emotional; therefore, support should be provided [30, 50]. Any disagreements identified should be negotiated with the patient, to come to a shared decision [24, 50, 55].

Patients may request burdensome treatments, in this case harm-reduction strategies should be chosen [55]. Considering this, all patients should set goals and plan for the future with their clinicians [50].

Clinicians should document all the information discussed and agreed, and should work closely with other professionals to ensure that the patient's wishes are fulfilled [26, 50]. Conversations should be restarted when new triggers arise or whenever the patient requires. [30, 50].

Discussion

The majority of studies included in the review showed that only a small percentage of patients with COPD had discussed palliative care with their clinicians. Clinicians in those studies reported several reasons behind this, such as the unpredictability of COPD, the fear of destroying patients' hope and the lack of understanding about palliative care and COPD by patients and physicians.

The small proportion of COPD patients who receive palliative care may be a reflection of the lack of conversations between patients and clinicians. However, the lack of accurate prognostic tools in COPD makes it difficult for clinicians to judge when the ideal time to initiate palliative care discussions is. Various tools have been suggested, but most of them have inadequate prognostic ability. For example, the tools used during the SUPPORT (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments) study showed that, at 5 days prior to death, patients with COPD were predicted to have >50% chance of surviving for 6 months [22]. Other tools can be included in this list, such as BODE (body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnoea, exercise capacity), DECAF (Dyspnoea, Eosinopenia, Consolidation, Acidaemia and atrial Fibrillation score) and DOSE (Dyspnoea, Obstruction, Smoking, Exacerbation index) score. DOSE score can be used as a prognostic instrument for mortality in COPD; however, only 57.1% of patients with the highest score died within 5 years of follow-up [58]. When looking at the BODE score, 63.2% of patients with the highest BODE score were still alive at 3 years [59]. This shows the unpredictability and complexity of COPD, and makes it challenging to predict with certainty when a patient is approaching the end of life. Therefore, early conversations about all aspects of the disease should be held and these should include discussions about palliative care interventions, as well as preferences for end-of-life care.

Another important factor when communicating palliative care with COPD patients was the patients' willingness to discuss this with a clinician. Most of the papers highlighted the importance of patients' willingness to discuss palliative care as a key factor to a successful discussion. Two studies showed that 33% of patients did not wish to discuss palliative care; however, further research looking into patients' willingness to discuss palliative care was not found. The recruitment of patients not willing to discuss this topic may have proved very difficult, hence, the lack of research in this area. The hypothetical explanation that led these patients to participate in the studies was that the studies targeted mainly healthcare professionals, instead of patients themselves. Despite this, several actions can be taken in clinical practice to reduce the impact of this, including: picking up cues about patients' readiness/willingness to discuss palliative care, slowly titrating the amount of information provided to patients about palliative care (this should be done according with the patient's own pace) and when patients/relatives raise this subject on their own.

The quality of end-of-life care communication was found to be poor and this was mainly because most topics were not discussed (refer to table 3 for further information). However, when topics were discussed the quality was found to be moderate to good. This suggests that the problem resided in the initiation of conversations and not in the clinicians' skills [39]. Therefore, it is suggested that healthcare professionals should make these conversations part of their day-to-day agenda. A lack of detailed information about the frequency and quality of conversations was also noted. If important topics were not discussed, the quality of communication related to these topics cannot be assessed. This leaves a large proportion of the conversation with unknown quality.

Patients with previous palliative care discussions were found to rate their medical care and their clinicians' skills higher than patients who did not. This may be because they had a discussion about preferences of care with their clinicians which meant that their wishes were respected and their care adjusted to their preferences. This suggests an important link between palliative care discussions and patient assessments of care quality and should be explored in future work. However, it was noted a paucity of in-depth information about the impact and the importance of conversations for patients so further qualitative research is required to explore the importance and impact of conversations, and to understand with certainty which factors of discussions have greater impact for patients.

Participants stated that the preferred clinician with whom to have the conversation was their general practitioner and the best place was within outpatient clinics or general practitioner appointments. Although participants reported that the best time was early in the disease trajectory, the majority of conversations happened very late in the disease trajectory. The need for earlier, planned and stress-free conversations make further research very important. Most of these data were generated from quantitative research, yet much could be gained from in-depth qualitative research specifically collecting information from patients describing the most appropriate timing, place and person to discuss palliative care, describing the reasons behind their choices and suggesting ways to achieve their preferences at all times.

Several studies tested the effect of interventions on improving the frequency and/or quality of palliative care discussions; however, all studies had a small impact on discussions. Only one study focused on improving and measuring physicians' skills at the end of the study [57], whilst the other studies focused on the impact of the interventions in improving the frequency and/or quality of discussions. This study concluded that only “responding to emotion” improved in clinicians' skills and that clinicians tended to lose their skills with time, especially when considering emotional empathy. Another study showed that when clinicians do discuss palliative care, their discussions are rated as moderate to good by patients [39]. This suggests that the quality and frequency of conversations were not linked with lack of skills of clinicians but with the high number of barriers for conversations and the difficulty in initiating them [36, 56, 57]. Hence, the little impact of interventions in improving discussions. Minimising the barriers for discussions about palliative care will greatly enhance their frequency and quality.

The frequency of end-of-life care conversations in cancer is remarkably similar to the frequency seen in COPD: 21–37% [60, 61]. However, several differences between patients with COPD and cancer were highlighted when considering these discussions. The majority of these differences are thought to be disease related and due to the awareness that the general public has of both diseases. Cancer brings the expectation of death and hence people with cancer expect conversations regarding ultimate prognosis and its impact on treatment and care; whereas, in COPD, the progression over time is variable and difficult to predict, consequently these aspects of care planning are not expected or requested [18]. Patients and healthcare professionals need further education regarding all illness-related aspects, including the inevitable life-limiting character of COPD.

Strengths and limitations

Our findings follow a systematic literature search and include data from only moderate- or high-quality papers, thus enriching the quality of the information presented and increasing reliability. Finally, the use of a narrative synthesis framework provided a systematic approach to process, analyse and synthesise the data extracted from the research studies.

Only papers written in English were included which may have excluded important information, potentially leading to cultural and demographic bias; however, only two papers fell into this category and had poor quality. A second limitation is the small number of papers, especially the lack of controlled trials and objective comparisons of approaches and their influence on outcomes for patients. Another limitation is the number of COPD patients contained in the papers. Papers were only included if their sample included at least 50% COPD patients; however, this may have only excluded a marginal amount of information. The last limitation was the use of one author when screening for papers in databases, websites, journals and reference lists. By having only one author screening the papers, this may have resulted in some papers being missed; however, to mitigate this, all authors agreed on the inclusion of all papers, the reference lists of the included papers and of papers related with the subject were screened and an objective search strategy was developed by all authors before the screening process.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current literature suggests that despite evidence of real benefit when conducted, the frequency and quality of palliative care conversations between patients and healthcare professionals is poor. Patients and physicians cite a large number of barriers, and most topics are not discussed. When discussions do take place, they do so at an advanced stage of disease, often in a busy, acute and stressful environment and often with clinicians who do not have an established relationship with the patient. Moreover, differences in experiences between patients with cancer and those with COPD suggest that long-standing inequalities based on diagnosis continue to pervade.

Given the relationship between conversations about care and the meeting of patient preferences, this lack of optimal communication between clinicians and patients is likely to impact upon care quality, patient satisfaction and, ultimately, the likelihood of a “good death”. Further research needs to be performed to guide development and testing of new pathways and practices to improve outcomes for COPD patients by ensuring timely and appropriate integrated palliative care and advance care planning through open discussions with healthcare professionals.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary tables 00068-2016_supplementary_tables (543.6KB, pdf)

Disclosures

T. Wilkinson 00068-2016_Wilkinson (1.2MB, pdf)

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside this article at openres.ersjournals.com

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Quality Standard. 2011. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs10/resources/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-in-adults-2098478 592709 Date last accessed: October, 2016.

- 2.Department of Health. An Outcomes Strategy for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Asthma in England, 2011 p. 56 Available from www.gov.uk/government/publications/an-outcomes-strategy-for-people-with-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd-and-asthma-in-england Date last accessed: October, 2016.

- 3.Sullivan KE, Hébert PC, Logan J, et al. What do physicians tell patients with end-stage COPD about intubation and mechanical ventilation? CHEST 1996; 109: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halldórsdóttir BS, Svavarsdóttir EK. Purposeful Therapeutic Conversations: Are they effective for families of individuals with COPD: A quasi-experimental study. Nordic J Nursing Res Clin Studies 2012; 32: 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Momen N, Hadfield P, Kuhn I, et al. Discussing an uncertain future: end-of-life care conversations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Thorax 2012; 67: 777–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson DM, Ross C, Goodridge D, et al. The care needs of community-dwelling seniors suffering from advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can J Aging 2008; 27: 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NICE. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. London, 2010. Available from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65039/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK65039.pdf Date last accessed: October, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith S, Kirkpatrick P. Use of solution-focused brief therapy to enhance therapeutic communication in patients with COPD. Primary Health Care 2013; 23: 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scullion J, Holmes S. Improving care for COPD. Independent Nurse, 2009: pp. 33–33.

- 10.World Health Association. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2016. Available from www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ Date last accessed: October, 2016.

- 11.World Health Organization. Palliative care for older people: better practices. Denmark, 2011. Available from www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/143153/e95052.pdf Date last accessed: October, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.NICE. End of life care for adults - Quality Standard, 2011 Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs13/resources/end-of-life-care-for-adults-2098483631557 Date last accessed: October, 2016.

- 13.Department of Health. End of Life Care Strategy - Fourth Annual Report, 2012, Department of Health. p. 73 Availalbe from www.gov.uk/government/publications/end-of-life-care-strategy-fourth-annual-report Date last accessed: October, 2016.

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Opioids for pain relief in palliative care overview, 2005, NICE: Manchester Available from https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/opioids-for-pain-relief-in-palliative-care Date last accessed: October, 2016.

- 15.Randall Curtis J. Palliative care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2006; 2: 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gore JM, Brophy CJ, Greenstone MA. How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax 2000; 55: 1000–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White P, White S, Edmonds P, et al. Palliative care or end-of-life care in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective community survey. Br J Gen Pract 2011; 61: e362–e370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawford A. Respiratory practitioners’ experience of end-of-life discussions in COPD. Br J Nurs 2010; 19: 1164–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, et al. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. CHEST 2012; 142: 128–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, et al. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J 2004; 24: 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Communication about palliative care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Care 2005; 21: 157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis JR. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J 2008; 32: 796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stephen N, Skirton H, Woodward V, et al. End-of-life care discussions with nonmalignant respiratory disease patients: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kass-Bartelmes BL, Hughes R. Advance care planning: preferences for care at the end of life. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2004; 18: 87–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis JR. Communicating with patients and their families about advance care planning and end-of-life care. Respir Care 2000; 45: 1385–1394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.You JJ, Fowler RA, Heyland DK. Just ask: discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ 2014; 186: 425–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews – CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. 2008. Available from www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf Date last accessed: November, 2016.

- 28.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009; 339: b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philip J, Gold M, Brand C, et al. Negotiating hope with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a qualitative study of patients and healthcare professionals. Intern Med J 2012; 42: 816–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halliwell J, Mulcahy P, Buetow S, et al. GP discussion of prognosis with patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2004; 54: 904–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, et al. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP), 1998. Available from www.ephpp.ca/PDF/Quality%20Assessment%20Tool_2010_2.pdf Date last accessed: May, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bromley H, Dockery G, Fenton C, et al. Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies. 2002; Available from: http://www.depts.ttu.edu/education/our-people/Faculty/additional_pages/duemer/epsy_5382_class_materials/Evaluating-Qualitative-Studies.pdf.

- 33.Saks M, Allsop J. Doing a Literature Review in Health. In: S.P. Ltd, ed. Researching Health: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods. London, SAGE Publications Ltd, 2007; pp. 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews - A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. 2006.

- 35.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. CHEST 2011; 139: 1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Au DH, Udris EM, Engelberg RA, et al. A randomized trial to improve communication about end-of-life care among patients with COPD. CHEST 2012; 141: 726–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knauft E, Nielsen EL, Engelberg RA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to end-of-life care communication for patients with COPD. CHEST 2005; 127: 2188–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seamark D, Blake S, Seamark C, et al. Is hospitalisation for COPD an opportunity for advance care planning? A qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21: 261–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. Patient-clinician communication about end-of-life care in patients with advanced chronic organ failure during one year. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 49: 1109–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elkington H, White P, Higgs R, et al. GPs’ views of discussions of prognosis in severe COPD. Fam Pract 2001; 18: 440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt M, Demoule A, Deslandes-Boutmy E, et al. Intensive care unit admission in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: patient information and the physician's decision-making process. Crit Care 2014; 18: R115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fahim A, Kastelik JA. Palliative care understanding and end-of-life decisions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Respir J 2014; 8: 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dexter PR, Wolinsky FD, Gramelspacher GP, et al. Effectiveness of computer-generated reminders for increasing discussions about advance directives and completion of advance directive forms. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998; 128: 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaspar C, Alfarroba S, Telo L, et al. End-of-life care in COPD: a survey carried out with Portuguese pulmonologists. Rev Port Pneumol 2014; 20: 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mulcahy P, Buetow S, Osman L, et al. GPs’ attitudes to discussing prognosis in severe COPD: an Auckland (NZ) to London (UK) comparison. Fam Pract 2005; 22: 538–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janssen DJ, Curtis JR, Au DH, et al. Patient-clinician communication about end-of-life care for Dutch and US patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2011; 38: 268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McNeely PD, Hébert PC, Dales RE, et al. Deciding about mechanical ventilation in end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: How respirologists perceive their role. CMAJ 1997; 156: 177–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006; 9: 1086–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curtis JR, Engelberg R, Young JP, et al. An approach to understanding the interaction of hope and desire for explicit prognostic information among individuals with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2008; 11: 610–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahia CL, Blais CM. Primary palliative care for the general internist: integrating goals of care discussions into the outpatient setting. Ochsner J 2014; 14: 704–711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, et al. Patients’ perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: Differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. CHEST 2002; 122: 356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reinke LF, Griffith RG, Wolpin S, et al. Feasibility of a Webinar for Coaching Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease on End-of-Life Communication. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2011; 28: 147–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morris DA, Johnson KS, Ammarell N, et al. What is your understanding of your illness? A communication tool to explore patients’ perspectives of living with advanced illness. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27: 1460–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reinke LF, Slatore CG, Uman J, et al. Patient-Clinician Communication about End-of-Life Care Topics: Is Anyone Talking to Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease? J Palliat Med 2011; 14: 923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quill TE, Arnold R, Back AL. Discussing treatment preferences with patients who want “everything”. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simpson AC. An opportunity to care? preliminary insights from a qualitative study on advance care planning in advanced COPD. Progress in Palliative Care 2011; 19: 243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szmuilowicz E, El-Jawahri A, Chiappetta L, et al. Improving residents’ end-of-life communication skills with a short retreat: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2010; 13: 439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sundh J, Janson C, Lisspers K, et al. The Dyspnoea, Obstruction, Smoking, Exacerbation (DOSE) index is predictive of mortality in COPD. Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21: 295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Esteban C, Quintana JM, Moraza J, et al. BODE-Index vs HADO-score in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Which one to use in general practice? BMC Med 2010; 8: 28–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008; 300: 1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169: 480–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary tables 00068-2016_supplementary_tables (543.6KB, pdf)

T. Wilkinson 00068-2016_Wilkinson (1.2MB, pdf)