Abstract

Background

We hypothesized that patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer (CRC) with COPD as a comorbidity would consume more resources and have worse in-hospital outcomes than similar patients without COPD. Therefore, we compared different aspects of the care process and short-term outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for CRC, with and without COPD.

Methods

This was a prospective study and it included patients from 22 hospitals located in Spain – 472 patients with COPD and 2,276 patients without COPD undergoing surgery for CRC. Clinical variables, postintervention intensive care unit (ICU) admission, use of invasive mechanical ventilation, and postintervention antibiotic treatment or blood transfusion were compared between the two groups. The reintervention rate, presence and type of complications, length of stay, and in-hospital mortality were also estimated. Hazard ratio (HR) for hospital mortality was estimated by Cox regression models.

Results

COPD was associated with higher rates of in-hospital complications, ICU admission, antibiotic treatment, reinterventions, and mortality. Moreover, after adjusting for other factors, COPD remained clearly associated with higher and earlier in-hospital mortality.

Conclusion

To reduce in-hospital morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing surgery for CRC and with COPD as a comorbidity, several aspects of perioperative management should be optimized and attention should be given to the usual comorbidities in these patients.

Keywords: COPD, colorectal cancer, in-hospital mortality, reintervention, complications

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC), one of the most common cancers in developed countries, has a 5-year survival rate of about 60%.1–3 Most patients are diagnosed at a relatively advanced age, when chronic comorbidities are often present. COPD is prevalent and commonly associated with other diseases.4,5

Surgery is essential in many cases of CRC and is associated with considerable mortality (up to 11% at 30 days) and a high rate of complications.6,7 Many factors are associated with outcomes after different types of surgery, and COPD has been associated with increased short-term mortality. However, few studies of postoperative outcomes in patients with COPD focus on patients with CRC or on postoperative outcomes other than mortality, such as reintervention, complications, or length of stay (LOS).8 Recently, Platon et al9 found COPD was a strong predictor of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and 30-day mortality after CRC surgery.9

Poorer outcomes after surgery in patients with COPD are related to respiratory failure or other postoperative complications, which can lead to higher short-term mortality. In patients undergoing abdominal surgery, the most common short-term complications include not only infection or other complications involving the site of surgery but also organ failure, including respiratory failure or ventilator problems. In patients with COPD, respiratory complications are probably even more common, adding complexity to immediate postoperative management and increasing the likelihood of worse outcomes.

Despite the prevalence and importance of COPD, few studies have analyzed the overall impact of COPD on postoperative (in-hospital) outcomes or on the use of resources in oncologic surgery in general or CRC surgery in particular. We hypothesized that patients undergoing surgery for CRC with COPD as a comorbidity would consume more resources and have worse in-hospital outcomes than similar patients without COPD. To test this hypothesis, we compared some aspects of the care process and short-term outcomes in two cohorts of patients (with and without COPD) undergoing surgery for CRC in diverse hospitals in Spain.

Methods

Design and patients

This prospective multicenter cohort study of patients from 22 hospitals located in nine regions of Spain was done in the framework of the REDISSEC-CARESS/CCR (Results and Health Services Research in Colorectal Cancer) study, which addressed diverse research objectives in hospitals treating CRC in Spain for the national health system.10 The hospitals’ size and technological resources varied widely. The Clinical Research Ethics Committees of the Parc Taulí Sabadell-University Hospital; Hospital del Mar; Fundació Unio Catalana d’Hospitals; Gipuzkoa Health Area; Basque Country; Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo; Hospital Txagorritxu; La Paz University Hospital; Fundación Alcorcón University Hospital; Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos (formerly Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Area 7 – Hospital Clínico San Carlos); and the Regional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Andalusia approved the study. All patients provided written informed consent.

We included patients undergoing scheduled or urgent surgery for primary invasive CRC in the period from June 2010 through December 2012, whether the goal of surgery was to excise the tumor or to palliate symptoms.

The REDISSEC-CARESS/CCR study excluded patients with only cancer in situ, those with relapsed tumors, those with cancer not located in the colon or rectum, those who died before surgery, those with inoperable cancer, and those transferred for surgery in another center.

Variables and data collection

Appropriately trained reviewers used a structured questionnaire and a manual to collect data from clinical records and interviews with surgeons about the following clinical variables: age, categorized as <80 years or ≥80 years; sex; smoking habit; chronic alcoholism; body mass index (BMI), calculated from the weight and height recorded in the clinical history, with BMI <18.5 considered low, 18.5–25 normal, and BMI >25 overweight/obese; baseline comorbidities included in the Charlson Index, with Charlson scores classified in three categories (0, 1–2, ≥3); tumor location (colon or rectum); American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (I–IV); urgency of the intervention; type of surgery (laparoscopic or open); and staging according to the AJCC.11

COPD (eg, emphysema and chronic bronchitis) was considered present when the diagnosis was mentioned in patients’ clinical charts. Asthma or other acute or chronic inflammatory diseases of the airways resulting in bronchospasm alone were not considered COPD. Likewise, diffuse interstitial fibrosis or sarcoidosis was not considered COPD.

We recorded the following process variables: postintervention ICU admission, use of invasive mechanical ventilation, and postintervention antibiotic treatment or blood transfusion.

Outcome variables were reintervention, major complications during the intervention, complications during the hospital stay (as described in Quintana et al10), and the LOS after the intervention grouped into four ranges (1–7 days, 8–15 days, 16–30 days, >30 days). For the purposes of this study, complications were classified by severity into three mutually exclusive categories (none, minor, major) according to the clinical judgment of the surgeons participating in the study, with major complications classified by type (infectious, hemorrhagic, surgical, vascular, or medical). In-hospital mortality was defined as any death occurring before discharge from hospital, independently of the duration of the hospital LOS.

Data analyses

A descriptive analysis of all variables was carried out. To compare patients with COPD versus those without COPD, we used chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. For process and outcome variables, we also estimated crude odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used logistic regression techniques, incorporating statistically or clinically significant variables in the bivariate analysis to estimate the adjusted risk of death during the hospital stay. To adjust for comorbidities, we took the Charlson scores into account. Thus, in addition to the variable COPD, the final regression model included the other significant variables that enabled the maximum discriminatory capacity of the model estimated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve with good calibration according to the Hosmer–Lemeshow test.

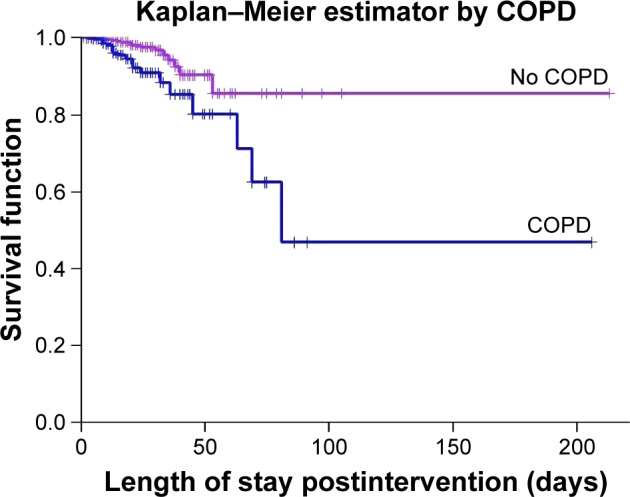

To estimate the probability of in-hospital death in function of the presence of COPD, we used Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, in which discharge was considered a censoring event. We compared the survival curves of patients with COPD versus those without COPD by log-rank test. We used Cox regression models to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) for hospital mortality, adjusted for the same factors or variables as in the logistic regression model.

We defined statistical significance as P<0.05, and we used IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics 23 and R statistical package 2.15.3 for the analyses.

Results

We analyzed a total of 2,748 patients with CRC (mean age, 68 years); of these, 472 (17.2%) had COPD. Table 1 compares the sociodemographic and clinical variables in patients with COPD versus those without COPD. The COPD group had higher proportions of men (80.5% vs 60.1%, P<0.001), patients aged ≥80 years (25.8% vs 14.7%, P<0.001), patients with chronic alcoholism (22.1% vs 11%, P<0.001), and patients with smoking habit (18.6% vs 12.2%, P<0.001). Moreover, Charlson scores were higher in patients with COPD because comorbidities were more common. Specifically, the following comorbidities were more common in patients with COPD than in those without COPD: heart failure (20% vs 7.6%, P<0.001), diabetes (26% vs 18%, P<0.001), peripheral vascular disease (10.9% vs 4%, P<0.001), peptic ulcers (11.4% vs 4.8%, P<0.001), and primary malignant tumors other than CRC (11.3% vs 6.7%, P<0.001). The most common comorbidities in patients with COPD were diabetes mellitus (25.8%), moderate to severe heart failure (20.3%), peptic ulcer (11.5%), malignant primary tumors other than CRC (11.3%), and peripheral vascular disease (10.9%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables in patients with COPD versus in those without, 2010–2012

| Variable | COPD

|

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N=2,276) |

Yes (N=472) |

||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 1,368 | 60.1 | 380 | 80.5 | |

| Female | 908 | 39.9 | 92 | 19.5 | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| <80 | 1,937 | 85.3 | 350 | 74.2 | |

| ≥80 | 335 | 14.7 | 122 | 25.8 | |

| Chronic alcoholism | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 1,915 | 89.0 | 352 | 77.9 | |

| Yes | 237 | 11.0 | 100 | 22.1 | |

| Smoking habit | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 1,980 | 87.8 | 376 | 81.4 | |

| Yes | 275 | 12.2 | 86 | 18.6 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.846 | ||||

| Low | 12 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Normal | 522 | 30.1 | 108 | 28.6 | |

| Overweight/obesity | 1,202 | 69.2 | 266 | 70.6 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Charlson Index | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 1,913 | 84.1 | 322 | 68.7 | |

| 1–2 | 299 | 13.1 | 124 | 26.4 | |

| ≥3 | 64 | 2.8 | 23 | 4.9 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 2,166 | 95.3 | 431 | 92.1 | |

| Yes | 106 | 4.7 | 37 | 7.9 | |

| Heart failure (moderate/severe) | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,104 | 92.4 | 376 | 79.7 | |

| Yes | 172 | 7.6 | 96 | 20.3 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,186 | 96.0 | 418 | 89.1 | |

| Yes | 90 | 4.0 | 51 | 10.9 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.299 | ||||

| No | 2,175 | 95.6 | 443 | 94.5 | |

| Yes | 101 | 4.4 | 26 | 5.5 | |

| Dementia | 0.301 | ||||

| No | 2,258 | 99.2 | 463 | 98.7 | |

| Yes | 18 | 0.8 | 6 | 1.3 | |

| Peptic ulcer | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,165 | 95.2 | 415 | 88.5 | |

| Yes | 110 | 4.8 | 54 | 11.5 | |

| Connective tissue disease | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 2,267 | 99.6 | 467 | 99.6 | |

| Yes | 9 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Liver disease | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,226 | 97.8 | 443 | 94.5 | |

| Yes | 50 | 2.2 | 26 | 5.5 | |

| Diabetes | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 1,866 | 82.0 | 348 | 74.2 | |

| Yes | 410 | 18.0 | 121 | 25.8 | |

| Renal failure (moderate/severe) | 0.079 | ||||

| No | 2,225 | 97.8 | 452 | 96.4 | |

| Yes | 51 | 2.2 | 17 | 3.6 | |

| Hemiplegia | 0.305 | ||||

| No | 2,265 | 99.5 | 465 | 99.1 | |

| Yes | 11 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.9 | |

| Leukemia, lymphoma, or any other tumor (past 5 years) | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,124 | 93.3 | 416 | 88.7 | |

| Yes | 152 | 6.7 | 53 | 11.3 | |

| Metastatic solid tumor (different from colorectal cancer) | 0.238 | ||||

| No | 2,256 | 99.1 | 468 | 99.8 | |

| Yes | 20 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| AIDS | – | ||||

| No | 2,276 | 100.0 | 469 | 100.0 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| ASA score | <0.001 | ||||

| I–II | 1,402 | 63.4 | 145 | 31.5 | |

| III | 751 | 34.0 | 269 | 58.5 | |

| IV | 59 | 2.7 | 46 | 10.0 | |

| Tumor and intervention | |||||

| Location | 0.554 | ||||

| Colon | 1,633 | 71.7 | 345 | 73.1 | |

| Rectum | 643 | 28.3 | 127 | 26.9 | |

| Stage | 0.193 | ||||

| I | 501 | 22.1 | 125 | 26.7 | |

| II | 798 | 35.2 | 156 | 33.3 | |

| III | 749 | 33.1 | 143 | 30.6 | |

| IV | 216 | 9.5 | 44 | 9.4 | |

| Urgency of intervention | 0.302 | ||||

| No | 2,197 | 96.5 | 451 | 95.6 | |

| Yes | 79 | 3.5 | 21 | 4.4 | |

| Type of surgery | 0.001 | ||||

| Laparoscopic | 1,342 | 59.6 | 237 | 50.9 | |

| Open | 910 | 40.4 | 229 | 49.1 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

No differences were observed between patients with COPD and those without COPD in the urgency of the intervention, CRC location, or CRC stage. Laparoscopic surgery was less common in patients with COPD (50.9% vs 59.6%, P<0.001). A greater proportion of patients with COPD were classified under ASA III (58.5% vs 34%, P<0.001) and IV (10% vs 2.7%, P<0.001) risk categories.

Table 2 compares the process and outcome variables in patients with COPD versus those without COPD.

Table 2.

Process and outcome variables in patients with COPD versus in those without, 2010–2012

| Variable | COPD

|

P-value | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N=2,276) |

Yes (N=472) |

|||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Complications | ||||||

| Severity of complications | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 1,193 | 52.4 | 177 | 37.5 | ||

| Minor | 481 | 21.1 | 114 | 24.2 | 1.597 (1.234–2.068) | |

| Major | 602 | 26.4 | 181 | 38.3 | 2.027 (1.611–2.549) | |

| Infectious (major) | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 2,021 | 88.8 | 388 | 82.2 | ||

| Yes | 255 | 11.2 | 84 | 17.8 | 1.716 (1.311–2.246) | |

| Hemorrhagic (major) | 0.286 | |||||

| No | 2,159 | 94.9 | 442 | 93.6 | ||

| Yes | 117 | 5.1 | 30 | 6.4 | 1.252 (0.828–1.895) | |

| Surgical (major) | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 2,004 | 88.0 | 380 | 80.5 | ||

| Yes | 272 | 12.0 | 92 | 19.5 | 1.784 (1.375–2.315) | |

| Vascular (major) | 0.035 | |||||

| No | 2,166 | 95.2 | 438 | 92.8 | ||

| Yes | 110 | 4.8 | 34 | 7.2 | 1.529 (1.027–2.276) | |

| Medical (major) | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 2,141 | 94.1 | 409 | 86.7 | ||

| Yes | 135 | 5.9 | 63 | 13.3 | 2.443 (1.779–3.355) | |

| Use of resources | ||||||

| Intensive care unit admission | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 1,743 | 76.6 | 325 | 68.9 | ||

| Yes | 533 | 23.4 | 147 | 31.1 | 1.479 (1.190–1.839) | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 0.027 | |||||

| No | 2,221 | 97.6 | 452 | 95.8 | ||

| Yes | 55 | 2.4 | 20 | 4.2 | 1.787 (1.061–3.011) | |

| In-hospital antibiotic treatment (postintervention) | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 1,274 | 56.0 | 223 | 47.2 | ||

| Yes | 1,002 | 44.0 | 249 | 52.8 | 1.420 (1.164–1.732) | |

| Blood transfusion | 0.444 | |||||

| No | 1,702 | 74.8 | 345 | 73.1 | ||

| Yes | 574 | 25.2 | 127 | 26.9 | 1.092 (0.872–1.366) | |

| Reintervention | 0.010 | |||||

| No | 2,106 | 92.5 | 420 | 89.0 | ||

| Yes | 170 | 7.5 | 52 | 11.0 | 1.534 (1.105–2.129) | |

| Postintervention LOS (days) | <0.001 | |||||

| 1–7 | 1,104 | 48.5 | 164 | 34.7 | ||

| 8–15 | 799 | 35.1 | 194 | 41.1 | 1.634 (1.303–2.051) | |

| 16–30 | 278 | 12.2 | 78 | 16.5 | 1.889 (1.399–2.549) | |

| >30 | 93 | 4.1 | 36 | 7.6 | 2.606 (1.715–3.959) | |

| In-hospital death | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 2,256 | 99.1 | 451 | 95.6 | ||

| Yes | 20 | 0.9 | 21 | 4.4 | 5.252 (2.824–9.770) | |

Abbreviations: LOS, length of stay; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

A greater proportion of patients with COPD developed complications during the hospital stay (62.5% in patients with COPD vs 47.5% in those without, P<0.001); likewise, a greater proportion of patients with COPD developed more severe complications (38.3% in patients with COPD vs 26.4% in those without, P<0.001). Major infectious, surgical, vascular, and medical complications were more common in patients with COPD. Table 3 reports the frequencies of specific major complications in patients with COPD and in those without. The infectious complications that were more common in patients with COPD than in those without were pneumonia and other respiratory tract infections, intravenous catheter infections, and septic shock. The main surgical complications that were more common in patients with COPD than in those without were the dehiscence of the surgical wound or anastomosis, evisceration, and vascular damage. The main medical complications that were more common in patients with COPD than in those without were cardiac arrest, heart failure, respiratory failure, and renal failure; the risk of major medical complications was 78%–235% higher in patients with COPD (OR 2.443; 95% CI 1.779–3.355).

Table 3.

Major complications in patients with COPD versus in those without COPD

| Type of complication | COPD

|

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N=2,276)

|

Yes (N=472)

|

||||

| N | %Col | N | %Col | ||

| Infectious | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,021 | 88.8 | 388 | 82.2 | |

| Yes | 255 | 11.2 | 84 | 17.8 | |

| Pneumonia | 0.018 | ||||

| No | 2,250 | 98.9 | 460 | 97.5 | |

| Yes | 26 | 1.1 | 12 | 2.5 | |

| Catheter infection | 0.006 | ||||

| No | 2,235 | 98.2 | 454 | 96.2 | |

| Yes | 41 | 1.8 | 18 | 3.8 | |

| Sepsis | 0.158 | ||||

| No | 2,266 | 99.6 | 467 | 98.9 | |

| Yes | 10 | 0.4 | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Septic shock | 0.030 | ||||

| No | 2,224 | 97.7 | 453 | 96.0 | |

| Yes | 52 | 2.3 | 19 | 4.0 | |

| Localized intra-abdominal infection (abscess) | 0.341 | ||||

| No | 2,204 | 96.8 | 453 | 96.0 | |

| Yes | 72 | 3.2 | 19 | 4.0 | |

| Peritonitis | 0.036 | ||||

| No | 2,212 | 97.2 | 450 | 95.3 | |

| Yes | 64 | 2.8 | 22 | 4.7 | |

| Deep surgical infection | 0.705 | ||||

| No | 2,211 | 97.1 | 457 | 96.8 | |

| Yes | 65 | 2.9 | 15 | 3.2 | |

| Respiratory tract infection | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,266 | 99.6 | 462 | 97.9 | |

| Yes | 10 | 0.4 | 10 | 2.1 | |

| Hemorrhagic complication | 0.286 | ||||

| No | 2,159 | 94.9 | 442 | 93.6 | |

| Yes | 117 | 5.1 | 30 | 6.4 | |

| Bleeding wound | 0.905 | ||||

| No | 2,225 | 97.8 | 461 | 97.7 | |

| Yes | 51 | 2.2 | 11 | 2.3 | |

| Internal bleeding of other organs | 0.074 | ||||

| No | 2,222 | 97.6 | 454 | 96.2 | |

| Yes | 54 | 2.4 | 18 | 3.8 | |

| Hemoperitoneum | 0.309 | ||||

| No | 2,255 | 99.1 | 465 | 98.5 | |

| Yes | 21 | 0.9 | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Surgical complication | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,004 | 88.0 | 380 | 80.5 | |

| Yes | 272 | 12.0 | 92 | 19.5 | |

| Wound leakage | 0.007 | ||||

| No | 2,214 | 97.3 | 448 | 94.9 | |

| Yes | 62 | 2.7 | 24 | 5.1 | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0.022 | ||||

| No | 2,193 | 96.4 | 444 | 94.1 | |

| Yes | 83 | 3.6 | 28 | 5.9 | |

| Evisceration | 0.003 | ||||

| No | 2,250 | 98.9 | 458 | 97.0 | |

| Yes | 26 | 1.1 | 14 | 3.0 | |

| Necrosis (abdominal wall) | 0.390 | ||||

| No | 2,269 | 99.7 | 469 | 99.4 | |

| Yes | 7 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Enterocutaneous fistula | 0.110 | ||||

| No | 2,249 | 98.8 | 462 | 97.9 | |

| Yes | 27 | 1.2 | 10 | 2.1 | |

| Biliary fluid in peritoneum | 0.530 | ||||

| No | 2,273 | 99.9 | 471 | 99.8 | |

| Yes | 3 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Urological injuries | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 2,266 | 99.6 | 470 | 99.6 | |

| Yes | 10 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Vascular injuries | 0.010 | ||||

| No | 2,272 | 99.8 | 467 | 98.9 | |

| Yes | 4 | 0.2 | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Neurological injuries | |||||

| No | 2,276 | 100.0 | 472 | 100.0 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other organ laceration | 0.099 | ||||

| No | 2,246 | 98.7 | 461 | 97.7 | |

| Yes | 30 | 1.3 | 11 | 2.3 | |

| Vascular | 0.035 | ||||

| No | 2,166 | 95.2 | 438 | 92.8 | |

| Yes | 110 | 4.8 | 34 | 7.2 | |

| Transient ischemic attack | 0.530 | ||||

| No | 2,273 | 99.9 | 471 | 99.8 | |

| Yes | 3 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.038 | ||||

| No | 2,274 | 99.9 | 469 | 99.4 | |

| Yes | 2 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Angor or acute myocardial infarction | 0.075 | ||||

| No | 2,171 | 95.4 | 441 | 93.4 | |

| Yes | 105 | 4.6 | 31 | 6.6 | |

| Medical complication | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,141 | 94.1 | 409 | 86.7 | |

| Yes | 135 | 5.9 | 63 | 13.3 | |

| Cardiac arrest | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,273 | 99.9 | 465 | 98.5 | |

| Yes | 3 | 0.1 | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Heart failure | 0.016 | ||||

| No | 2,244 | 98.6 | 458 | 97.0 | |

| Yes | 32 | 1.4 | 14 | 3.0 | |

| Kidney failure | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,224 | 97.7 | 447 | 94.7 | |

| Yes | 52 | 2.3 | 25 | 5.3 | |

| Respiratory problems/failure | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2,215 | 97.3 | 438 | 92.8 | |

| Yes | 61 | 2.7 | 34 | 7.2 | |

| Intestinal obstruction | 0.166 | ||||

| No | 2,254 | 99.0 | 464 | 98.3 | |

| Yes | 22 | 1.0 | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Multiorgan failure | 0.076 | ||||

| No | 2,267 | 99.6 | 467 | 98.9 | |

| Yes | 9 | 0.4 | 5 | 1.1 | |

Abbreviation: %Col, column percentage.

The greater incidence of complications in patients with COPD was also associated with greater consumption of resources during the hospital stay, longer LOS, and higher in-hospital mortality (Table 2). Greater proportions of patients with COPD were admitted to the ICU (31.1% vs 23.4%; OR 1.5), received invasive mechanical ventilation (4.2% vs 2.4%; OR 1.8), and received antibiotics after the intervention (53% vs 44%; OR 1.4). Moreover, a greater proportion of patients with COPD required reintervention (11% vs 7.5%; OR 1.5). However, no differences in hemorrhagic complications or blood transfusions were observed between the two groups.

The overall mean LOS after the intervention was 12.4±11.1 days (median 9, range 1–213). COPD was associated with longer LOS. Only 35% of the patients with COPD spent less than a week in hospital after the intervention compared to 48.5% of those without COPD. There was also a trend in the strength of the association between COPD and longer LOS, being especially strong for LOS >30 days (OR 2.606; 95% CI 1.715–3.959).

A total of 41 (1.5%) patients died in hospital. The risk of death was higher in patients with COPD (OR 5.252; 95% CI 2.824–9.770); after adjustment for the significant variables (age, sex, tumor location, ASA risk, and reintervention), the OR was 3.514 (95% CI 1.662–7.429) and the HR was 2.480 (95% CI 1.228–5.006).

The survival curves (Figure 1) show that death occurred earlier in patients with COPD than in those without (log-rank test 14.458; P=0.000). The most common causes of death in patients with COPD were septic shock and medical complications.

Figure 1.

In-hospital survival function in patients with and without COPD.

Discussion

In this nationwide study of patients undergoing surgery for CRC, we found that COPD was associated with higher rates of postoperative complications, ICU admission, antibiotic treatment, reinterventions, and mortality during hospitalization. Moreover, after adjusting for other factors, COPD remained clearly associated with higher and earlier in-hospital mortality.

Previous nationwide studies in the USA found that even after adjusting for other clinical factors, COPD clearly increases postoperative morbidity and mortality (up to 30 days) and LOS in patients undergoing all types of surgery and in patients undergoing all types of abdominal surgery.8,12 Our results show that these findings are also valid for the more specific group of patients undergoing surgery for CRC in a nationwide sample in Spain.

The prevalence of COPD in our cohort (17%) is similar to that reported in other settings, although differences in important factors make comparisons among studies difficult. A previous study in our setting reported 19% prevalence of COPD in patients undergoing surgery for rectal cancer;13 however, the prevalence of COPD was lower in the aforementioned studies in more general surgical populations: 5% in Gupta et al’s cohort and 3.8% in Fields and Divino’s cohort. COPD is more common in cancer patients, in part, due to the history of smoking habit. In our study, COPD patients were identified concurrently with data collection. Despite the difficulties inherent in this design, it does not seem that the prevalence of COPD has been underestimated.

The only study published to date that focuses on COPD in CRC interventions reported 13% 30-day mortality in patients with COPD, about 70% higher than in those without COPD; these figures varied with different clinical variables.9

The in-hospital mortality rate in our study was low, but it was four times higher in patients with COPD than in those without, remaining significant after adjusting for sex, age, ASA risk, tumor location, and reintervention. Furthermore, patients with COPD died earlier after the intervention, underlining the importance of optimizing pulmonary function when possible and maintaining closer postoperative surveillance in these patients.

The most common causes of death in patients with COPD are respiratory disease and cardiovascular disease.14,15 As reported in other studies,16–18 the prevalence of heart failure and respiratory insufficiency were higher in patients with COPD than in those without. This clinically important difference could explain the higher rates of ICU admission and invasive mechanical ventilation in COPD patients. On the other hand, our COPD patients also had a higher rate of infectious complications after surgery than patients without COPD, which explains, in part, their higher rate of postoperative antibiotic treatment. Among infectious complications, septic shock, pneumonia, and other respiratory tract infections were especially prevalent.

Interestingly, COPD patients in our study had higher rates of wound or anastomosis dehiscence, and even evisceration, partially explaining their higher rate of reintervention. Platon et al9 reported similar findings. The higher rates of these surgical complications in patients with COPD are not surprising: coughing is both a frequent symptom of COPD and a common cause of wound dehiscence; many COPD patients receive oral glucocorticoids that delay wound healing; and many lack good nutritional status essential for wound healing.19 All these factors explain the longer LOS in patients with COPD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with COPD undergoing surgery for CRC, several aspects of perioperative management are important: bronchodilator therapy, postoperative analgesia, and respiratory physiotherapy should be optimized and attention should be given to the usual comorbidities in these patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially financed by grants PS09/00314, PS09/00910, PS09/00746, PS09/00805, PI09/90460, PI09/90490, PI09/90397, PI09/90453, PI09/90441, RD12/0001/0007 – Research Network on Health Services in Chronic Diseases (REDISSEC) of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

We are grateful to the patients who voluntarily took part in this study and to the doctors, interviewers, and research committees at the participating hospitals (Hospital de Antequera, Hospital Costa del Sol, Hospital Universitario de Valme, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Parc Taulí University Hospital, Althaia, Hospital del Mar, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Hospital Infanta Sofía, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Hospital Universitario Araba, Hospital Universitario Basurto, Hospital Universitario Cruces, Hospital de Donostia, Hospital de Bidasoa, Hospital de Mendaro, Hospital de Zumarraga and Hospital Universitario Doctor Peset). We also want to thank the editorial assistance provided by John Giba. The members of the REDISSEC CARESS-CCR group are: Jose María Quintana,a Marisa Baré,b Maximino Redondo,c Eduardo Briones,d Nerea Fernández de Larrea,e Cristina Sarasqueta,f Antonio Escobar,g Francisco Rivas,h Maria M Morales-Suárez,i Juan Antonio Blasco,j Isabel del Cura,k Inmaculada Arostegui,l Amaia Bilbao,g Nerea González,a Susana García-Gutiérrez,a Iratxe Lafuente,a Urko Aguirre,a Miren Orive,a Josune Martin,a Ane Antón-Ladislao,a Núria Torà,m Marina Pont,m María Purificación Martínez del Prado,n Alberto Loizate,o Ignacio Zabalza,p José Errasti,q Antonio Z Gimeno,r Santiago Lázaro,s Mercè Comas,t Jose María Enríquez,u Carlos Placer,u Amaia Perales,v Iñaki Urkidi,w Jose María Erro,x Enrique Cormenzana,y Adelaida Lacasta,z Pep Piera Pibernat,z Elena Campano,A Ana Isabel Sotelo,B Segundo Gómez-Abril,C F Medina-Cano,D Julia Alcaide,E Arturo Del Rey-Moreno,F Manuel Jesús Alcántara,G Rafael Campo,H Alex Casalots,I Carles Pericay,J Maria José Gil,K Miquel Pera,K Pablo Collera,L Josep Alfons Espinàs,M Mercedes Martínez,N Mireia Espallargues,O Caridad Almazán,P Paula Dujovne Lindenbaum,Q José María Fernández-Cebrián,Q Rocío Anula Fernández,R Julio Ángel Mayol,R Ramón Cantero,S Héctor Guadalajara,T María Heras,T Damián García,T Mariel Morey,U Javier Mar.V

aUnidad de Investigación, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Galdakao-Bizkaia/Red de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas – REDISSEC, bClinical Epidemiology and Cancer Screening, Parc Taulí University Hospital, Sabadell/Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona-UAB/REDISSEC, cServicio de Laboratorio, Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga/REDISSEC, dUnidad de Epidemiología, Distrito Sevilla, Servicio Andaluz de Salud, eCentro Nacional de Epidemiología, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid/CIBERESP, fUnidad de Investigación, Hospital Universitario Donostia/Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Biodonostia, Donostia – REDISSEC, gUnidad de Investigación, Hospital Universitario Basurto, Bilbao/REDISSEC, hServicio de Epidemiología, Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga – REDISSEC, iDepartment of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Valencia/(CIBERESP)/CSISP-FISABIO, Valencia, jUnidad de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias, Agencia Laín Entralgo, Madrid, kUnidad Apoyo a Docencia-Investigación, Dirección Técnica Docencia e Investigación, Gerencia Adjunta Planificación, Gerencia de Atención Primaria de la Consejería de Sanidad de la Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, lDepartamento de Matemática Aplicada, Estadística e Investigación Operativa, UPV-REDISSEC, mEpidemiologia Clínica y Cribado de Cancer, Parc Taulí University Hospital, Sabadell/REDISSEC, nServicio de Oncología, Hospital Universitario Basurto, Bilbao, oServicio de Cirugía General, Hospital Universitario Basurto, Bilbao, pServicio de Anatomía Patológica, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Galdakao, qServicio de Cirugía General, Hospital Universitario Araba, Vitoria-Gasteiz, rServicio de Gastroenterología, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, La Laguna, sServicio de Cirugía General, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Galdakao, tIMAS-Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, uServicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva, Hospital Universitario Donostia, vInstituto de Investigación Sanitaria Biodonostia, Donostia, wServicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva, Hospital de Mendaro, xServicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva, Hospital de Zumárraga, yServicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva, Hospital del Bidasoa, zServicio de Oncología Médica, Hospital Universitario Donostia, AInstituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla, BServicio de Cirugía, Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme, Sevilla, CServicio de Cirugía General y Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Dr Pesset, Valencia, DServicio de Cirugía General y Aparato Digestivo, Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol, Marbella, EServicio de Oncología Médica, Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol, Marbella, FServicio de Cirugía, Hospital de Antequera, GColoproctology Unit, General and Digestive Surgery Service, Parc Taulí University Hospital, Sabadell, HDigestive Diseases Department, Parc Taulí University Hospital, Sabadell, IPathology Service, Parc Taulí University Hospital, Sabadell, JMedical Oncology Department, Parc Taulí University Hospital, Sabadell/REDISSEC, KGeneral and Digestive Surgery Service, Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, LGeneral and Digestive Surgery Service, Althaia – Xarxa Assistencial Universitaria, Manresa, MCatalonian Cancer Strategy Unit, Department of Health, Institut Català d’Oncología, NMedical Oncology Department, Institut Català d’Oncología, OAgency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia – AQuAS and REDISSEC, PAgency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia – AQuAS, CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública – CIBERESP, QServicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid, RServicio de Cirugía General y Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, SServicio Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía, San Sebastián de los Reyes, Madrid, TServicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, UREDISSEC, Unidad de Apoyo a la Investigación, Gerencia Asistencial de Atención Primaria de la Comunidad de Madrid, Madrid, VREDISSEC, Unidad de Gestión Sanitaria, Hospital del Alto Deba. Mondragon-Arrasate, Spain.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [Accessed July 8, 2016]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H, et al. CONCORD Working Group Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009: analysis of individual data for 25, 676, 887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2) Lancet. 2015;385(9972):977–1010. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allemani C, Rachet B, Weir HK, et al. Colorectal cancer survival in the USA and Europe: a CONCORD high-resolution study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003055. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, Badamgarav E, Buist AS, Mannino DM. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(3):523–532. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00124605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soriano JB, Ancochea J, Miravitlles M, et al. Recent trends in COPD prevalence in Spain: a repeated cross-sectional survey 1997–2007. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(4):758–765. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazaure HS, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Association of postdischarge complications with reoperation and mortality in general surgery. Arch Surg. 2012;147(11):1000–1007. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baré M, Alcántara M, Gil MJ, et al. Validity of the CR-POSSUM model in surgery for colorectal surgery in Spain (CARESS-CCR Study) and comparison with other models to predict operative mortality. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2839-x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta H, Ramanan B, Gupta PK, et al. Impact of COPD on postoperative outcomes: results from a national database. Chest. 2013;143(6):1599–1606. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Platon AM, Erichsen R, Christiansen CF, et al. The impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on intensive care unit admission and 30-day mortality in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a Danish population-based cohort study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2014;1(1):e000036. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2014-000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quintana JM, Gonzalez N, Anton-Ladislao A, et al. REDISSEC-CARESS/CCR group Colorectal cancer health services research study protocol: the CCR-CARESS observational prospective cohort project. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:435. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2475-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fields AC, Divino CM. Surgical outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing abdominal operations: an analysis of 331,425 patients. Surgery. 2016;159(4):1210–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espallargues M, Almazán C, Tebé C, et al. ONCOrisc Study Group Management and outcomes in digestive cancer surgery: design and initial results of a multicenter cohort study. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101(10):680–696. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082009001000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGarvey LP, John M, Anderson JA, Zvarich M, Wise RA, TORCH Clinical Endpoint Committee Ascertainment of cause-specific mortality in COPD: operations of the TORCH Clinical Endpoint Committee. Thorax. 2007;62(5):411–415. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.072348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolton CE, Quint JK, Dransfield MT. Cardiovascular disease in COPD: time to quash a silent killer. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(9):687–689. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong DH, Weber EC, Schell MJ, Wong AB, Anderson CT, Barker SJ. Factors associated with postoperative pulmonary complications in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Anesth Analg. 1995;80(2):276–284. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199502000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemmens VE, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Houterman S, et al. Which comorbid conditions predict complications after surgery for colorectal cancer? World J Surg. 2007;31(1):192–199. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0711-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Lawrence VA, Theroux JF, Tuley MR, Hilsenbeck S. Postoperative complications after thoracic and major abdominal surgery in patients with and without obstructive lung disease. Chest. 1993;104(5):1445–1451. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.5.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Ramshorst GH, Nieuwenhuizen J, Hop WC, et al. Abdominal wound dehiscence in adults: development and validation of a risk model. World J Surg. 2010;34(1):20–27. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0277-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]