Abstract

Objectives

To understand why mortality increased in England and Wales in 2015.

Design

Iterative demographic analysis.

Setting

England and Wales

Participants

Population of England and Wales.

Main outcome measures

Causes and ages at death contributing to life expectancy changes between 2013 and 2015.

Results

The long-term decline in age-standardised mortality in England and Wales was reversed in 2011. Although there was a small fall in mortality rates between 2013 and 2014, in 2015 we then saw one of the largest increases in deaths in the post-war period. Nonetheless, mortality in 2015 was higher than in any year since 2008. A small decline in life expectancy at birth between 2013 and 2015 was not significant but declines in life expectancy at ages over 60 were. The largest contributors to the observed changes in life expectancy were in those aged over 85 years, with dementias making the greatest contributions in both sexes. However, changes in coding practices and diagnosis of dementia demands caution in interpreting this finding.

Conclusions

The long-term decline in mortality in England and Wales has reversed, with approximately 30,000 extra deaths compared to what would be expected if the average age-specific death rates in 2006–2014 had continued. These excess deaths are largely in the older population, who are most dependent on health and social care. The major contributor, based on reported causes of death, was dementia but caution was advised in this interpretation. The role of the health and social care system is explored in an accompanying paper.

Keywords: Non-clinical, public health, life expectancy, social care crisis, health service crisis

Introduction

Europe has experienced sustained reductions in mortality in the post-war period, driven by improved living conditions, lifestyles and better healthcare. Elsewhere, developments have not always been so favourable and, where progress is interrupted, it has often indicated deeper societal problems. The observation that infant mortality in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was increasing in the 1980s1 was a pointer to broader problems. The recent worsening of life expectancy in the USA is causing concern,2 especially as worsening health indicators were the strongest predictors of electoral gains by Donald Trump.3

There are now growing concerns about the United Kingdom. Deaths in 2015 were substantially greater than in 2014, representing the greatest percentage increase for almost 50 years. This increase seems to be continuing in 2016, with the number of weekly deaths since mid-October 2016 exceeding that in any of the preceding three years (Web appendix). Yet, while this has attracted attention in official circles, the explanation is far from clear. Early analyses of the provisional data for 2015 reportedly left experts ‘grasping for answers’.4 Delay in release of detailed mortality data means that initial assessments were based on incomplete data and, of necessity, proposed explanations were somewhat speculative. While some attributed the rise to influenza, suggesting that cold weather may have played a part, others asked whether it could be linked to health and social care cuts,4 citing research linking increasing mortality at older ages in England between 2007 and 2013 to cuts in welfare spending.5 Public Health England argued that the deaths were ‘not exceptional’6 noting that the influenza strain in 2015 was influenza A (H3N2), a strain they consider affects older people predominantly.

It is now possible to test the explanations that have been proposed with detailed mortality data from 2015 available for England and Wales. In this, the first of two linked papers, we describe what happened to mortality in 2015 and explore a range of possible explanations. In the second paper, we look in detail at one particular aspect of the increase in mortality in 2015, a large increase in deaths in January of that year, again considering possible explanations.

Methods

We adopted an iterative approach, interrogating data to understand the nature of the phenomenon as far as possible. We first define the scale of the problem, assessing the magnitude of the increase in mortality and reporting basic descriptive analyses. After standardising for age, we place what happened in 2015 in a historical context. We then examine how mortality varied over the course of 2015 and compare this with what happened in previous years.

Having confirmed that mortality did rise substantially in 2015, with a corresponding fall in life expectancy, we then turn to life expectancy at various ages, assessing statistical significance of changes and identifying the contributors to the decline in life expectancy in terms of cause of death by sex and at different ages. We use the Office for National Statistics (ONS) methodology to estimate the standard errors of life expectancy at 5-year-age increments. To identify the contributors to observed changes, we use Arriaga’s method of decomposition,7 which allows us to identify which causes of death, at which ages, contributed to the changes in life expectancy, whether positively or negatively. The initial inspection showed that the increase in mortality was greatest among those at older ages and from certain causes common at those ages. Based on this, and consideration of causes that have been invoked in earlier investigations of this phenomenon, we selected a limited number of causes of death of interest (Table 1). These differ from other studies using this method, which typically focus on deaths at younger ages.

Table 1.

Causes of death used in the decomposition of differences in life expectancy.

| ICD-10 Code | Description |

|---|---|

| J09; J10-J11.3 | Influenza due to certain identified influenza virus, Influenza |

| J12-J18 | Pneumonia |

| J40-44 | Bronchitis, emphysema and other chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| F01, F03 | Vascular and unspecified dementia |

| G20 | Parkinson disease |

| G30 | Alzheimer’s disease |

| C00-D48 | Neoplasms |

| U509, V01-Y80 | External causes of morbidity and mortality |

| I00-I99 | Diseases of the circulatory system |

| N/A | All other causes |

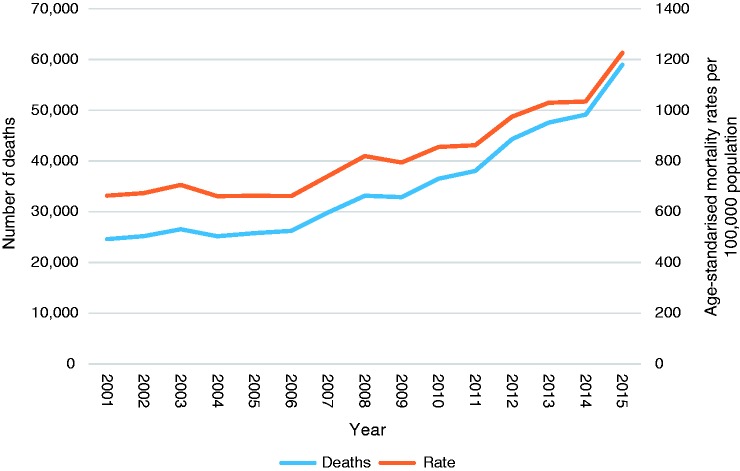

Having confirmed that deaths at older ages contributed most to worsening life expectancy, we turn to the predominant cause of death in this age group: dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We examine trends in number of deaths and age-standardised mortality rates (ASMR) from ONS data, along with the potential impact of changes in coding and recording of dementia and AD on death certificates.

Results

Defining the problem

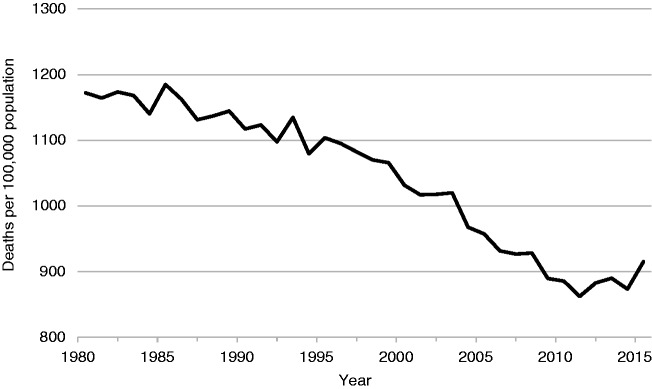

The overall number of deaths in 2015, at 529,655 deaths, was 28,231 more than 2014, an increase of 5.6%.8,9 However, meaningful comparisons require absolute numbers to be related to the population at risk, adjusted for the age composition of the population. Figure 1 shows that, following many years of decline, albeit with some year-to-year fluctuations, the downward ASMR trend does reverse after 2011 so that, by 2015, it was higher than in any year since 2008 and was 4.8% higher than in 2014 and 2.8% higher than in 2013, reflecting the small mortality decline between 2013 and 2014.

Figure 1.

Age-standardised death rate per 100,000 population, England and Wales, 1980–2015.

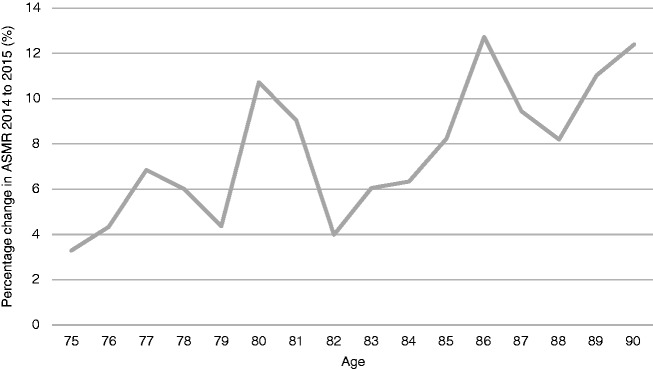

These figures are age-standardised using 5-year age groups. With a rapidly ageing population, it is necessary to exclude the possibility of a shift in the distribution of the population within each group. To address this issue, we have calculated the percentage change in the death rate at individual years of age between 2014 and 2015. As Figure 2 shows, at ages over 75, there is an increase at each age. We also applied age-specific death rates by single year of age in 2014 to the mid-year population in 2015 to estimate the difference from what would have been seen had there been no change in death rates. This reveals an excess of 33,798 deaths.

Figure 2.

Percentage increase in death rates at individual years over 75 from 2014 to 2015, England and Wales. Source: Authors’ calculations from ONS mortality data and population estimates.

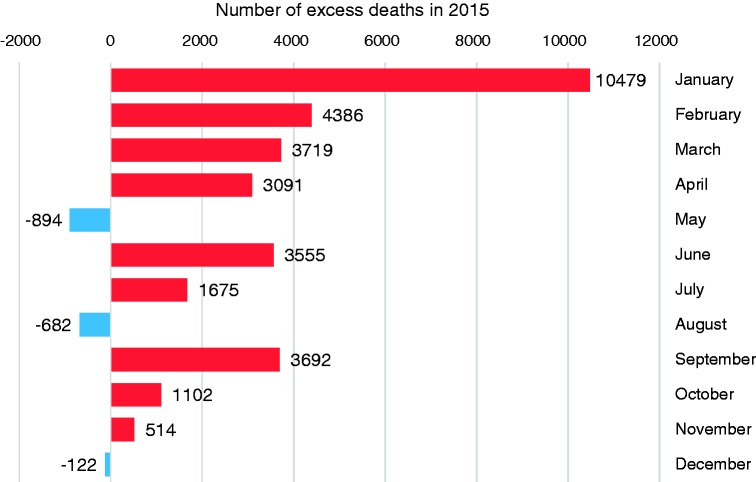

Having shown that the increase in deaths departs from previous trends and cannot be explained by population ageing, we next ask whether the increase varied during the year. When deaths in each month in 2015 are compared with monthly averages for the period 2006 to 2014 (Figure 3), the increase was in all but three months, but with a particularly large increase in January, when deaths were 24.2% higher than in 2014. This increase alone accounts for an excess of 10,479 deaths compared to what was expected had mean monthly deaths in 2006–2014 occurred.10 Over the entire year, the excess deaths number 30,515. Note that calculations of excess deaths in this paper vary slightly due to differences in standardisation in the various comparisons.

Figure 3.

Excess deaths per month in 2015 compared to the monthly average 2006–2014, England and Wales.

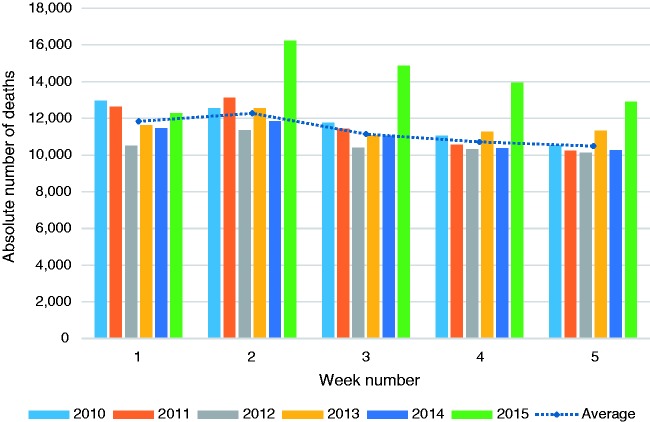

Looking in more detail at deaths in the first five weeks of each year (to ensure all of January is included) since 2010, 2015 clearly stands out (Figure 4).10 Other than in week 1, there were many more deaths in every week of January than in the same weeks in the previous years (dotted line shows average for the 5-year period 2010–2014). The accompanying paper will explore this finding in detail.

Figure 4.

Number of deaths per week, weeks 1–5, 2010–2015, England and Wales.

Contribution of deaths from different causes, at different ages, to the change in life expectancy

We now examine in detail the deaths contributing to recent changes in life expectancy. Although the deterioration was greatest between 2014 and 2015, we focus on the change between 2013 and 2015 in recognition of the slight improvement in 2014. Figures in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. There was a small but non-significant deterioration in life expectancy at birth, from 81.22 (81.18–81.25) years in 2013 to 81.17 (81.13–81.20). However, this includes a small increase of 0.03 years among men, due entirely to fewer deaths at young ages that compensated for the increase mortality at older ages, and a larger decline, of 0.1 year among women. At older ages, the declines are significant. At age 65, life expectancy fell from 19.91 (19.88–19.93) in 2013 to 19.84 (19.82–19.86) in 2015. The corresponding figures at age 75 were from 12.39 (12.37–12.40) years to 12.28 (12.26–12.29) years.

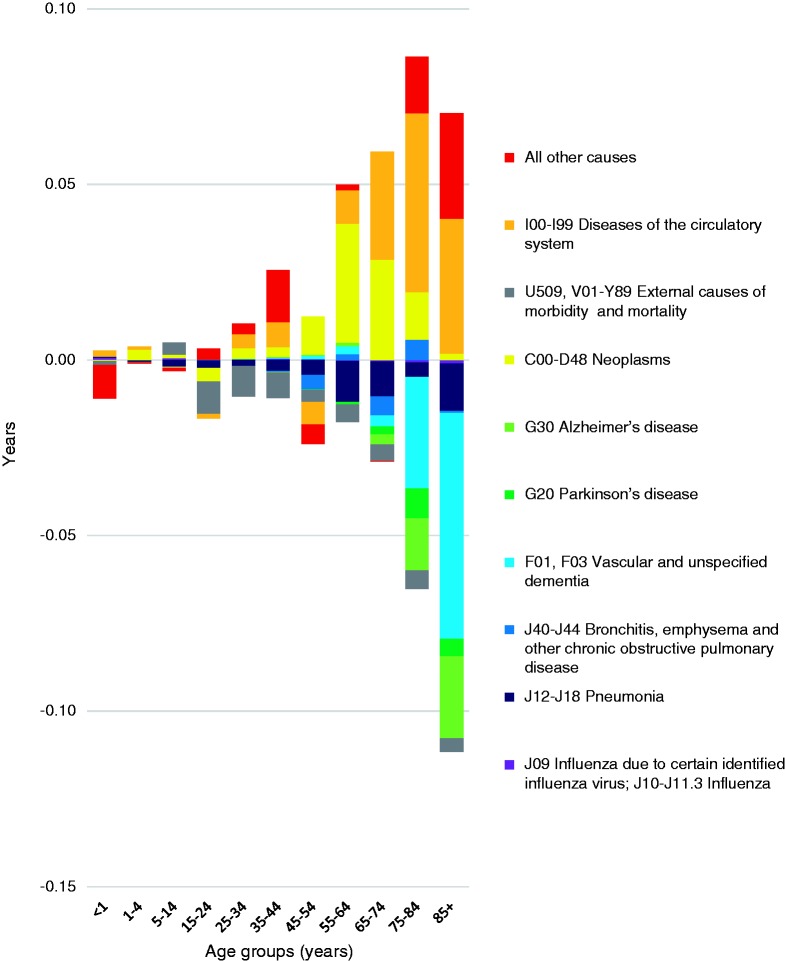

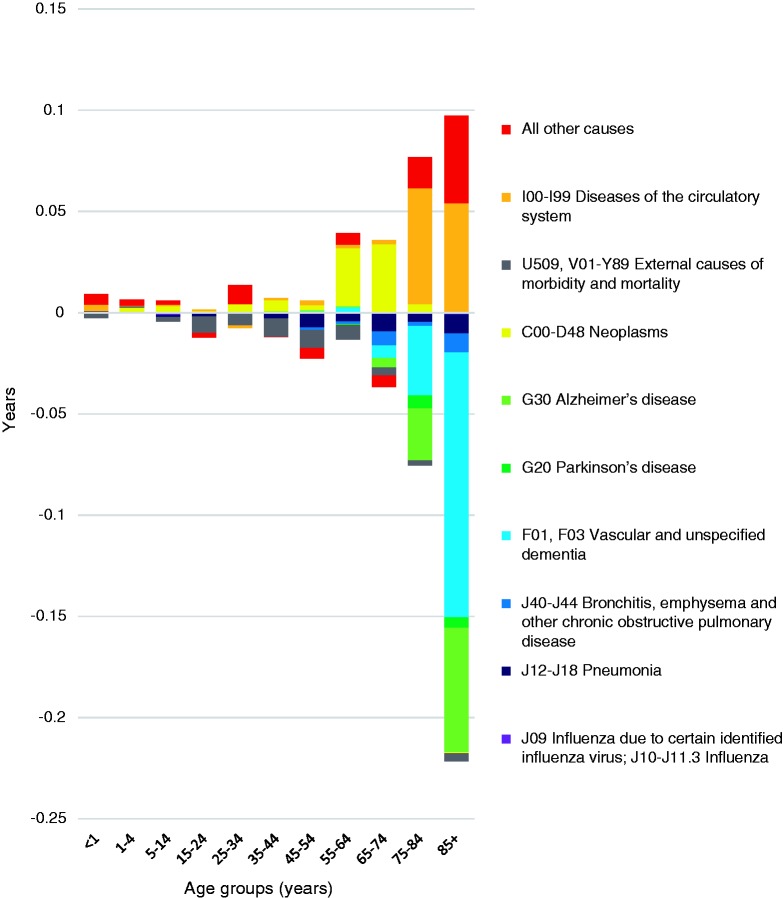

Figures 5 and 6 show the results of the decomposition of changes in life expectancy for both sexes, by age band and cause of death, in England and Wales. Bars above the line indicate that a fall in deaths contributed positively to life expectancy and vice versa. The corresponding figures for the change between 2014 and 2015, accompanied by a commentary on the findings, are included in a web appendix.

Figure 5.

Decomposition showing the contribution of deaths at different ages from different causes to change in male life expectancy, England and Wales, 2013–2015.

Figure 6.

Decomposition showing the contribution of deaths at different ages from different causes to change in female life expectancy, England and Wales, 2013–2015.

As expected, given the changes in life expectancy at each age, the largest contributors to change in life expectancy in both sexes were seen in the over 85 age band. Notably, influenza did not significantly contribute to changes in any group, although caution is needed as coding practices can record complications of influenza as the cause of death, such as pneumonia, rather than influenza itself.

For men, continuing reductions in deaths from diseases of the circulatory system and ‘all other causes’ made positive contributions to improved life expectancy in the ‘85 and over’ age band (0.04 and 0.03 years, respectively). The greatest contributors to worsening life expectancy were dementias, with vascular and unspecified dementia contributing a loss of 0.06 years, and AD a loss of 0.02 years. Pneumonia, responsible for a loss of 0.01 years, may include some deaths due to influenza. All age bands from 65 years and over saw a negative contribution of vascular and unspecified dementia, but the younger age groups experienced a positive contribution. Deaths at younger ages contributed very little to the worsening life expectancy, except those <1 years, where ‘all other causes’ contributed a loss of 0.01 years.

For women, during the years 2013 to 2015, the overwhelming negative contribution was from deaths in the over 85 age band, with vascular and unspecified dementia contributing a loss of 0.13 years and AD 0.06 years. Increasing deaths from pneumonia were the third most important cause of declining life expectancy, contributing 0.01 years, while deaths from diseases of the circulatory system and ‘all other causes’ made a modest positive contribution to life expectancy. As with men, increasing deaths from dementia impacted negatively from 65 years on, with modest positive contributions seen at younger ages. These findings indicate that increasing deaths in the over 75 years contributed most to the reduction in life expectancy, with dementias the predominant cause.

Changes in reported deaths from dementia

Given the frequency of multi-morbidity,11 coupled with the challenges of attributing deaths at older ages to a specific cause, it is important to ensure that the changes observed are not a function of changes in recording or coding. We now consider this possibility for the dementias, noting that the initial data show an upward acceleration in deaths attributed to both dementia and AD, above the trend line in 2015 (Figure 7).12

Figure 7.

Number of deaths and age-standardised mortality rates for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, persons 75 and over, England and Wales, 2001–2015.

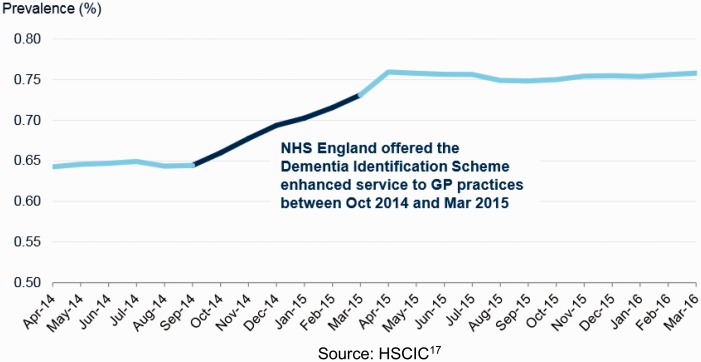

Our findings must, however, be interpreted in the context of other changes at the time. Historically, AD and dementia have rarely been recorded as a cause of death.13,14 The ONS codes deaths using specialist software and highly trained coders, and in January 2014, the software package was changed.15 This change has been associated with a 7.1% increase in deaths coded with an underlying cause as dementia.15 In addition, financial incentives encouraging early diagnosis of dementia in primary care were put in place between October 2014 and March 2015. That was associated with a marked increase in recorded prevalence, as seen in Figure 8.16,17 In contrast, epidemiological research using standardised diagnostic criteria show a declining age-standardised prevalence of dementia,18 although in terms of absolute numbers, this is counteracted by population ageing. However, it is important to note that the overall rise in mortality is not due to population ageing.

Figure 8.

Recorded prevalence of dementia, all ages, England, 2014/15 to 2015/16. Source: HSCIC.17

In summary, while the change in coding cannot explain the increase from 2014 to 2015, the incentives for early diagnosis may contribute in part. This cannot explain the increase in overall deaths but does caution against reading too much into the apparent rise in deaths from dementia.

Discussion

The results show a rise in deaths for the whole of 2015 but also a large spike in January, of necessity examined in a separate accompanying paper. Yet, even without it, mortality in 2015 would have increased. The decomposition revealed that deaths among those aged 75 and over contributed most to changes in life expectancy, with dementias the predominant cause. Changes in coding and diagnosis of dementia makes the data difficult to interpret, but, even so, it is not clear why more people would have died from dementia, if the figures are taken at face value.

As noted above, attributing a specific cause of death to older people is recognised to be challenging, given the presence of multi-morbidity. However, the causes of death that contribute to the increase share the characteristic of being either a cause of frailty in older people or a common terminal event. This pattern, coupled with the earlier finding of an increase in deaths throughout the year, suggest a general failure of care for this group, whose members are typically dependent on others for many aspects of their daily life. Clearly, many live lives that are precarious, at risk of infections, falls and fractures, so the question is not why any particular individual died but why, after many years of declining mortality, their death rate should increase so much?

This study has many limitations, largely arising from the limitations in the data available. For example, at the time of analysis, data by single year of age in each area were not available. Published data on the number of deaths in England and Wales varied – if weekly deaths are totaled, the figure is 539,007, equating to 37,583 excess deaths compared to 2014, and a rise of 7.5%.10 As such, even now this can only be considered a preliminary analysis, although we believe that we have gone as far as the data available to us currently allow. However, this raises an important question about the priority given to monitoring the health of the population. Almost 30,000 excess deaths have occurred, yet, as far as we can ascertain, this has stimulated no significant interest among politicians. A search of Hansard reveals only one question from a Member of Parliament (MP) about mortality in 2015. Scottish Nationalist Party MP, Ian Blackford, asked ‘The Minister will be aware that mortality rates in England and Wales have increased by 5.4% in 2015—the biggest increase in the death rate for decades. She will also be aware that mortality rates have been rising since 2011. Has she done any analysis of what has been behind those trends?’ and received the reply ‘We welcome the overall trend towards longer life expectancy. There are annual fluctuations, but overall the trend remains positive. The key thing is helping people to live longer, healthier lives’.19 Two further questions were asked by Dr Sarah Wollaston following communication about our research.

Our findings must be seen in the context of the severe disruption to the operation of the ONS following its move from London to Newport, with the loss of many key staff and institutional memory, coupled with severe cuts to its budgets – changes that have been blamed for the downgrading of the quality of the UK’s trade statistics.20 Given the delays and problems we have faced, there is a strong case for viewing the strengthening of ONS as a strategic national priority.

The older population particularly relies on a functioning health and social care system, and it has been suggested that the increase in mortality 2015 could be related to austerity and the resulting health and social care cuts.4,21 There is already evidence linking austerity and increasing suicide rates22 and dependence on food banks.23 One study has examined in detail changes in life expectancy in England in the years 2007 to 2013,5 finding a close correlation with cuts in pension credits at the level of local authorities. These funds provide an important source of income for the poorest pensioners. Although these findings predate the current increase in mortality, they offer a possible clue.

For those working in health and social care, the impact of austerity is already clear, with one survey of general practitioners finding that 94% of respondents reported that their workload had increased as a direct result of the financial hardship of their patients.24 Recent reports from the British Medical Association (BMA)25 and the Royal College of Physicians26 have both highlighted the serious public health consequences of austerity and the underfunding of the NHS, with the BMA calling for ‘robust action’ to mitigate the adverse impacts. It is not possible, with the limited data currently available, to explore this hypothesis in more detail, at least as it relates to deaths throughout the year, but some further clues can be found in the second part of our analysis, of the January 2015 spike in mortality.

In addition, cuts to local authorities’ budgets have resulted in the withdrawal of many services that older people depend on. Rural bus routes have been reduced dramatically, increasing isolation of those dependent on them.27,28 Meals on wheels services have been stopped in a third of top tier councils, with the National Association of Care Catering (NACC) drawing attention to the consequences, noting how a daily visit can reduce loneliness and isolation, prevent admission to hospital by supporting independent living and reducing medical problems resulting from malnutrition.29 Given these circumstances, it is unsurprising that, in 2014–2015, 29.2% of those 80 years and above reported high levels of loneliness.30

Conclusion

Approximately 30,000 more people died in 2015 than 2014 in England and Wales, with the increase in year on year deaths the greatest since World War II. Decomposition methods showed that the deaths in those over 75 years contributed most to changes in life expectancy, with dementias the predominant cause recorded. Changes in diagnosis and coding of dementia likely had an impact on these figures, and as such this should be interpreted with caution. What is clear is that the older population, who rely heavily on a well-functioning health and social care system, were the most harmed by the mortality increase.

With no satisfactory explanation provided for this increase so far, the accompanying paper in this series will aim to explore possible causes for such a rise in mortality, along with closer consideration of the impact of the cuts to the health and social care system.

Declarations

Competing interests

MM, DD and DH are unpaid members of public health England’s mortality surveillance advisory group. LH has no competing interests.

Funding

None declared.

Guarantor

LH.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the London school of hygiene and tropical medicine board for the initial dissertation project.

Contributorship

LH is a postgraduate student at LSHTM, under the supervision of MM. Having noted the increase in mortality and suggested explanation of ‘flu’, they decided to explore this possibility with help of the expertise of DH and DD. Using all publically available data from the Office for National Statistics, NHS England and Public Health England, the analyses and hypotheses were developed and explored. LH wrote the paper initially as her dissertation under Prof McKee’s supervision. Dr Hiam then converted this into the two present papers with substantial input from MM and ongoing advice from DD and DH, each of whom have extensive experience in research on mortality patterns and trends.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Marina Karanikolos for methodological advice.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Julie Morris and peer reviewers' comments from a previous submission were also made available.

References

- 1.Eberstadt N. The health crisis in the USSR. New York Rev Books 1981; 28: 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD and Arias E. Mortality in the United States. NCHS Data Brief, No 267. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2016.

- 3.The Economist. Illness as Indicator. See http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21710265-local-health-outcomes-predict-trumpward-swings-illness-indicator (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 4.Hawkes N. Sharp spike in deaths in England and Wales needs investigating, says public health expert. BMJ 2016; 352: i981–i981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loopstra R, McKee M, Katikireddi SV, Taylor-Robinson D, Barr B, Stuckler D. Austerity and old-age mortality in England: a longitudinal cross-local area analysis, 2007–2013. J R Soc Med 2016; 109: 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkes N. Recent high death rates in older people are not exceptional, says Public Health England. BMJ 2013; 347: f5252–f5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auger N, Feuillet P, Martel S, Lo E, Barry AD, Harper S. Mortality inequality in populations with equal life expectancy: Arriaga’s decomposition method in SAS, Stata, and Excel. Ann Epidemiol 2014; 24: 575–580. 80.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Office for National Statistics. Deaths Registered in England and Wales 2015. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregistrationsummarytables/2015 (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 9.Office for National Statistics. Vital Statistics: Population and Health Reference Tables. See http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/vitalstatisticspopulationandhealthreferencetables (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 10.Office for National Statistics. Weekly Provisional Figures on Death Registrations in England and Wales. See http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/weeklyprovisionalfiguresondeathsregisteredinenglandandwales (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 11.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012; 380: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office for National Statistics. Provisional Analysis of 2015 Death Registrations in England and Wales. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/provisionalanalysisof2015deathregistrationsinenglandandwales (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 13.Todd S, Barr S, Passmore AP. Cause of death in Alzheimer’s disease: a cohort study. QJM 2013; 106: 747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero JP, Benito-Leon J, Louis ED, Bermejo-Pareja F. Under reporting of dementia deaths on death certificates: a systematic review of population-based cohort studies. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2014; 41: 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office for National Statistics. Impact of the Implementation of IRIS Software for ICD-10 Cause of Death Coding on Mortality Statistics, England and Wales. See http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/impactoftheimplementationofirissoftwareforicd10causeofdeathcodingonmortalitystatisticsenglandandwales/2014-08-08 (2014, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 16.NHS England. Dementia Identification Scheme. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/dementia-ident-schm-fin.pdf (2014, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 17.Knight K. Patients in England diagnosed with dementia. HSCIC. See http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB20618/qual-outc-fram-rec-dem-diag-2015-2016-sum.pdf (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 18.Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, Bond J, Jagger C, Robinson L, et al. A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. Lancet 2013; 382: 1405–14012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.House of Commons Hansards. Topical Questions. See https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2016-05-10/debates/16051027000024/TopicalQuestions?highlight=mortality%202015-contribution-16051027000170 (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 20.O’Connor S. Office for National Statistics criticised over UK trade data errors. Financial Times. See https://www.ft.com/content/aeea9a3e-07ae-11e5-9579-00144feabdc0 (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 21.Dorling D. Brexit: the decision of a divided country. BMJ 2016; 354 i3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Scott-Samuel A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ 2012; 345: e5142–e5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loopstra R, Reeves A, Taylor-Robinson D, Barr B, McKee M, Stuckler D. Austerity, sanctions, and the rise of food banks in the UK. BMJ 2015; 350: h1775–h1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iacobucci G. GPs’ workload climbs as government austerity agenda bites. BMJ 2014; 349: g4300–g4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.British Medical Association. Health in All Policies: Health, Austerity and Welfare Reform, London: British Medical Association, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royal College of Physicians. Underfunded. Underdoctored. Overstretched. The NHS in 2016, 21 September 2016.

- 27.Disney J. After brutal spending cuts, rural bus services have reached the end of the line. The Conversation. See https://theconversation.com/after-brutal-spending-cuts-rural-bus-services-have-reached-the-end-of-the-line-63432 (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 28.Dorling D. Austerity, rapidly worsening public health across the UK, and Brexit. Political Studies Association. See https://www.psa.ac.uk/insight-plus/blog/austerity-rapidly-worsening-public-health-across-uk-and-brexit-0 (2016, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 29.National Association of Care Catering. Letter to MP: Meals on Wheels. See http://www.thenacc.co.uk/assets/downloads/675/MP Letter.pdf (2015, last checked 28 January 2017).

- 30.Office for National Statistics. Measuring National Well-being: Insights into Loneliness, Older People and Well-being. See http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/measuringnationalwellbeing/2015-10-01 - tab-Introduction (2015, last checked 28 January 2017).