Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the length of the interval between the onset and the initial management of bipolar disorder (BD).

Method:

We conducted a meta-analysis using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Systematic searches located studies reporting estimates of the age of onset (AOO) and indicators of the age at initial management of BD. We calculated a pooled estimate of the interval between AOO and age at management. Factors influencing between-study heterogeneity were investigated using sensitivity analyses, meta-regression, and multiple meta-regression.

Results:

Twenty-seven studies, reporting 51 samples and a total of 9415 patients, met the inclusion criteria. The pooled estimate for the interval between the onset of BD and its management was 5.8 years (standardized difference, .53; 95% confidence interval, .45 to .62). There was very high between-sample heterogeneity (I 2 = 92.6; Q = 672). A longer interval was found in studies that defined the onset according to the first episode (compared to onset of symptoms or illness) and defined management as age at diagnosis (rather than first treatment or first hospitalization). A longer interval was reported among more recently published studies, among studies that used a systematic method to establish the chronology of illness, among studies with a smaller proportion of bipolar I patients, and among studies with an earlier mean AOO.

Conclusions:

There is currently little consistency in the way researchers report the AOO and initial management of BD. However, the large interval between onset and management of BD presents an opportunity for earlier intervention.

Keywords: meta-analysis, bipolar disorders, age of onset, clinical management, duration of untreated bipolar disorder

Abstract

Objectif:

Évaluer la durée de l’intervalle entre l’apparition et la prise en charge initiale du trouble bipolaire (TB).

Méthode:

Nous avons mené une méta-analyse à l’aide des lignes directrices des éléments de rapport à privilégier pour les revues systématiques et les méta-analyses. Des recherches systématiques ont repéré des études faisant état des estimations de l’âge d’apparition (ADA) et des indicateurs de l’âge lors de la prise en charge initiale du TB. Nous avons calculé une estimation regroupée de l’intervalle entre l’ADA et l’âge à la prise en charge. Les facteurs influençant l’hétérogénéité entre les études ont été recherchés à l’aide d’analyses de sensibilité, de méta-régression et de multiple méta-régression.

Résultats:

Vingt-sept études, comportant 51 échantillons et un total de 9 415 patients satisfaisaient aux critères d’inclusion. L’estimation regroupée de l’intervalle entre l’apparition du TB et sa prise en charge était de 5,8 ans (écart normalisé = 0,53; Intervalle de confiance à 95% 0,45 à 0,62). L’hétérogénéité entre échantillons était très élevée (I-carré = 92,6; valeur Q = 672). Un intervalle plus long a été observé dans les études qui définissaient l’apparition en fonction du premier épisode (comparativement à l’apparition de symptômes ou de la maladie), et définissaient la prise en charge comme étant l’âge au diagnostic (plutôt qu’au premier traitement ou à la première hospitalisation). Un intervalle plus long était rapporté dans les études publiées plus récemment, dans les études qui utilisaient une méthode systématique pour établir la chronologie de la maladie, dans les études ayant une proportion moindre de patients bipolaires I et dans les études ayant un ADA moyen plus précoce.

Conclusions:

Il y a présentement peu de cohérence dans la manière dont les chercheurs rapportent l’ADA et la prise en charge initiale du TB. Toutefois, le large intervalle entre l’apparition et la prise en charge du TB offre l’occasion d’une intervention précoce.

The interval between the onset of bipolar disorder (BD) and initial management is important because early intervention might improve the prognosis or even prevent some cases.1 Early intervention is a well-developed concept in the field of first-episode psychosis, where there are widely accepted definitions, reliable instruments for measuring the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP),2,3 and some consensus that earlier treatment is associated with a better prognosis.4,5 Research into the early phase of BD is less developed. Currently, there are no widely agreed on definitions of the onset and initial management of BD, and the effect of treatment delay on the outcome of BD is unknown. The onset of BD is difficult to define prospectively because early symptoms can include both depression and attenuated mania, which can be difficult to distinguish from normal fluctuations in mood. The age at initial management of BD is also hard to define, because patients might have had medication or counselling for a range of less severe mood disorders long before a firm diagnosis of BD is made, usually following the first distinct episode of mania.

A pooled estimate of the interval between the age of onset (AOO) of what was, in retrospect, recognized to be emerging BD and the age of initial management of the condition might help guide future research into the effect of treatment delay on prognosis. Early detection of BD might allow interventions based on symptom profiles, patterns of cognitive function, or biomarkers.6 A better understanding of the extent of the interval between onset and management of BD might also help improve the performance of available mental health services by increasing the focus on early intervention and even prevention of BD.7

We report a meta-analysis of the period of time between the AOO and the age of initial management of BD, referred to here as the interval. The term management is used rather than treatment, because the contact with services may have resulted in a range of interventions that often did not include specific treatment for BD. The aims of the study were to calculate a pooled estimate of this interval and to explore possible reasons for the variation in this interval between studies.

Methods

The methods are based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.8

Searches

A systematic search of English and non-English (Italian, French, and German) language publications indexed in the electronic databases PubMed, Web of Science, and Psychology Behavioural Science Collection from inception to 31 July 2014 was conducted using the search string ‘onset AND bipolar’ in the title or abstract. The reference lists of relevant articles were hand-searched to locate additional studies not identified by electronic searches. The authors of studies that appeared relevant were contacted and asked for unpublished data that met our inclusion criteria, including for the Pearson’s correlation between the AOO and age at management in each included study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Two investigators independently (A.P. and G.S.) screened the article titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant studies, duplicate studies, other meta-analyses, reviews, case reports, and small case series (<3 subjects). Potentially relevant articles were independently examined in full text by 2 researchers (M.B. and J.D.) applying predetermined eligibility criteria. Where 2 or more studies reported overlapping samples, priority was given to the study with the largest samples size. An assessment of interrater reliability was made by calculating agreement around 10% of the screened titles and abstract articles (Cohen’s κ = 0.90) and around 10% of the examined full texts (Cohen’s κ = 0.83).

Studies were included if they

reported on cohorts of patients with BD, including BD I, BD II, and BD not otherwise specified;

provided data on the mean AOO of BD (defined as the AOO of symptoms, the onset of mood syndromes, or an episode or illness onset); and

provided data on the mean age of first management of BD (defined as age at first treatment, first diagnosis, or first hospitalization).

Studies were excluded if they

reported mixed samples of bipolar and schizophrenia spectrum disorders or did not separate those disorders;

reported the duration between the onset of BD and the initial management, without data regarding sample size, mean age, and standard deviation for both measures;

were studies of affective psychosis; and

reported on age-specific populations, such as older (>64 years) or younger (<14 years) patients.

Data Extraction

Two authors independently recorded the data using a proforma. Disagreements were resolved by further examination and by consensus.

The following data were extracted:

Sample size

Mean age and standard deviation of indicators of the AOO of BD using the definitions provided in the primary research. When a study reported multiple data points indicating the onset of BD, first choice was age at first symptoms, second choice was first episode of mood disorder, and the last choice was AOO of disorder or illness.

Mean age and standard deviation of indicators of the age of initial management of BD using the definitions provided in the primary research. Where studies reported multiple data points indicating the age of initial management, we used age at first treatment in preference to age at diagnosis, followed by age at first hospitalization.

The proportion of men in each sample

The year of publication of the study

The proportion of patients with BD I

The proportion of patients with substance or alcohol abuse

Data points for a strength of reporting scale

Strength of Reporting Scale

A 5-point strength of reporting scale was adapted from items suggested by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies.9 One point was awarded to studies that

restricted the definition of onset of BD to the AOO of symptoms or the AOO of episode of mood disorder,

provided AOO of initial treatment rather than age at diagnosis or first hospitalization,

used the life chart method or described another specific chronological method for assigning AOO and management,

used a structured interview rather than clinical assessment alone to confirm the diagnosis of BD, and

had a sample size of more than 30.

Meta-Analysis

A meta-analytical estimate of the standardized mean difference of the interval between the AOO and initial management was computed using a random-effects model. This interval was also calculated in years. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic and Q value. A random-effects meta-analysis was chosen on an a priori basis for all analyses because of the differences in the samples and in the definitions used. Publication bias was assessed using an Eggers regression test and Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill method.10 All analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3 (Biostat, Eaglewood, NJ, USA), and all significance testing used a 2-tailed test with a significance level of 0.05.

The contribution to between-study heterogeneity that might be explained by the 3 definitions of the AOO of BD and the 3 indicators of the age of initial management was examined in subgroup analyses. Further subgroup analyses were performed to examine the potential contribution of the way in which the diagnosis of BD was confirmed (clinically vs. using a structured diagnostic instrument) and how the chronology of the onset was determined (using a life chart or specified chronological method vs. a clinical method). A final subgroup analysis examined the contribution of strength of reporting to between-study heterogeneity (studies with a reporting strength score of ≤2 vs. those with a reporting strength of ≥3).

A mixed effects meta-regression model was used to assess the contribution to between-study heterogeneity in the interval between onset and management of the continuous variables of the proportion of males, the proportion of patients with BD I, the year of publication, and the mean AOO. Moderator variables that contributed to between-study heterogeneity at an α of 0.05 were included in a random-effects multiple meta-regression model.

Results

Searches and Data Extraction

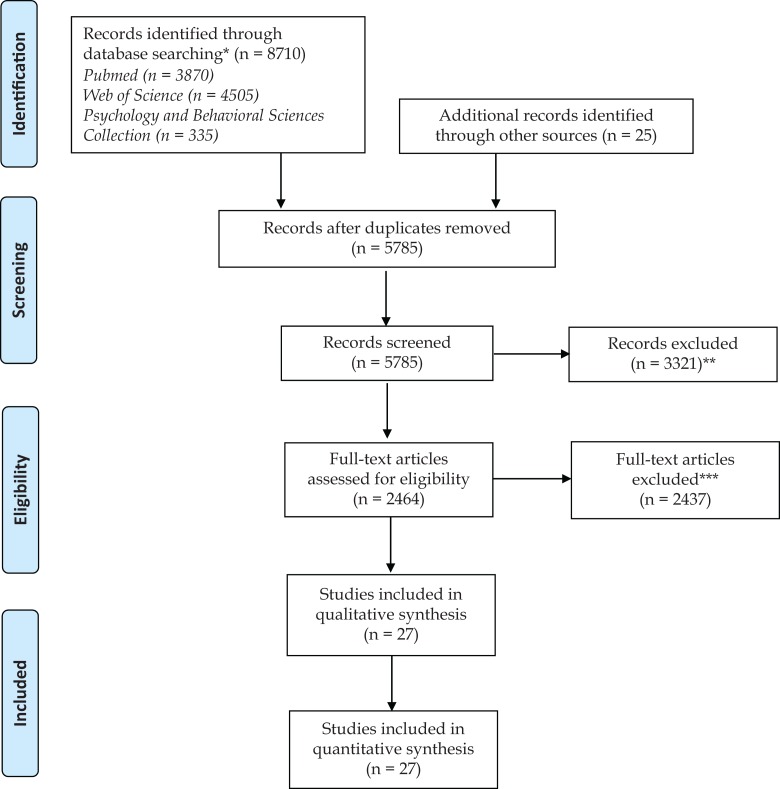

Figure 1 depicts the literature search and the study selection process. Twenty-seven studies reporting on 9415 subjects in 51 separate samples were included in the meta-analysis (Table 1). Differences in data extraction were found in relation to the effect size in 4 of the 27 studies: these differences were resolved by further examination and consensus.

Figure 1.

Age of onset in bipolar disorders. *Search performed on 31 July 2014, using the search string “onset AMD bipolar.” **Exclusion of irrelevant studies, duplicated studies, other meta-analyses, reviews, case reports, and small case series (<3 subjects). ***Studies not reporting mean age, standard deviation, and sample size for age at onset and management of bipolar disorder; studies with mixed samples of bipolar and schizophrenia spectrum disorders; studies with overlapping samples (priority was given to studies with the largest samples size reported on an age-specific populations, such older [>64 years] or younger [<14 years] patients); and studies reporting only measure of onset or measure of initial management (only studies presenting both measures were included).

Table 1.

Included Studies.

| Study Author | Location and Setting | Sample | Method to Confirm the Diagnosis of BD | Use of Specific Chronology Method for Assessing AOO and Management | Definition of AOO of BD | Definition of Initial Management of BD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akiskal et al. (2003)11 | Multicentre study, France | 196 (144 female, 52 male) patients with BD II | DSM-IV, BD diagnosed using semistructured interview and Checklist of Hypomania | No | Age at first symptoms | Age at first hospitalisation |

| Ancin et al. (2010)12 | Inpatients and outpatients from Madrid, Spain | 143 (84 female, 59 male) patients with BD I (115) or BD II (28) | DSM-IV, SCID | No | Age at onset of BD | Age at first hospitalisation |

| Carballo et al. (2008)13 | Inpatients and outpatients of 2 university hospitals in Pennsylvania and New York State, United States | 168 (85 female, 83 male) patients with BD | DSM-III-R, SCID | No | Age at onset of BD | Age at first hospitalisation |

| Cha et al. (2009)14 | Inpatients at Seoul National University Hospital, Korea | 258 (140 female, 118 male) patients with BD I | DSM-III-R or DSM-IV, clinical diagnosis | No | Age of first major mood episode | Age at diagnosis |

| Col et al. (2014)15 | Outpatients from Ankara, Turkey | 78 (50 female, 28 male) patients with BD I | DSM-IV, semistructured interview | No | Age at onset of BD | Age at first treatment |

| Dell’Osso et al. (1993)16 | Inpatients from a binational study from Pisa, Italy, and Tennessee, United States | 51 female patients with bipolar mania | DSM-III-R, clinical diagnosis | Yes | Age at first symptoms | Age at first treatment |

| Dienes et al. (2006)17 | Outpatients recruited in Los Angeles, United States | 58 (29 female, 29 male) patients with BD I | DSM-IV, SCID | No | Age of first mood episode | Age at diagnosis |

| Drancourt et al. (2013)18 | Outpatients recruited from university clinics in France | 401 (292 female, 209 male) patients with BP I (418) or BP II (83) | DSM-IV, DIGS | No | Age at first mood episode | Age at first treatment |

| Goldberg et al. (2002)19 | Outpatients from a specialist bipolar clinic, New York, United States | 56 (21 female, 35 male) patients with BD I (46) or BD II (7) | DSM-IV, SCID | Yes | Age at first symptoms | Age at diagnosis |

| Gutierrez-Rojas et al. (2008)20 | Outpatients from Jaen, Spain | 108 (75 female, 33 male) patients with BD | DSM-IV, clinical diagnosis | No | Age at onset of BD | Age at diagnosis |

| Haro et al. (2006)21 | Inpatients from a multicentre European study | 3536 (1953 female, 1584 male) patients with bipolar mania | DSM-IV or ICD-10, clinical diagnosis | No | Age at first symptoms | Age at first hospitalisation |

| Lee and Dunner (2008)22 | Outpatients from a university clinic in Seattle, United States | 44 (26 female, 18 male) patients in a depressed phase of BD I (12), BD II (16), and BD NOS (16) | DSM-IV-TR, semistructured interview | No | Age at onset of symptoms | Age at first treatment |

| Lex et al. (2011)23 | Inpatients and out patients from Vienna and Villach, Austria | 26 (11 female, 15 male) patients with BD I | DSM-IV, clinical diagnosis | No | Age at first mood episode | Age at first treatment |

| Lieberman et al. (2010)24 | Volunteers recruited Washington, United States | 282 (221 female, 71 male) patients with BD I (87), BD II (117), and BD NOS (78) | DSM-IV-R | Yes | Age at first mood episode | Age at diagnosis |

| Loranger et al. (1978)25 | Inpatients from New York, United States | 200 (100 female, 100 male) patients with bipolar mania | DSM-III, clinical diagnosis | No | Age at first symptoms | Age at first treatment |

| Marangell et al. (2008)26 | Trial participants from Texas, United States | 9 (7 female, 2 male) patients with rapid-cycling BD | DSM-IV-R | No | Age of first symptoms | Age at diagnosis |

| Mazzarini et al. (2010)27 | Outpatients from Barcelona, Spain | 164 (92 female, 72 male) patients with BD II | DSM-IV-TR, clinical diagnosis | No | Age at onset of BD | Age at first hospitalisation |

| Meeks (1999)28 | Outpatients from Kentucky, United States | 86 (64 female, 22 male) patients with BD I (74) or BD II (12) | RDC, SADS | Yes | Age at first symptoms | Age at first treatment |

| Nivoli et al. (2014)29 | Outpatients from Barcelona, Spain | 593 (326 female, 267 male) patients with BD I (332), BD II (120) and BD NOS (18) | DSM-IV-TR, SCID | Yes | Age at onset of BD | Age at first hospitalisation |

| Okan Ibiloglu et al. (2011)30 | Outpatients from Ankara, Turkey | 96 (67 female, 29 male) patients with BD I (50) or BD II (46) | DSM-IV, SCID | No | Age at onset of BD | Age at first treatment |

| Paholpak et al. (2014)31 | Outpatient and inpatients from a multicentre study, Thailand | 424 (258 female, 166 male) patients with BD I (64) or BD II (146) | DSM-IV, MINI | No | Age at onset of mood disturbancea | Age at first treatment |

| Parker et al. (2013)32 | Outpatients recruited from a specialist clinic, NSW, Australia | 210 (133 female, 177 male) patients with BD I (98) or BD II (534) | DSM-IV, MINI | No | Age at first manic episode | Age at diagnosis |

| Perugi et al. (2000)33 | Inpatients from Pisa, Italy | 320 (179 female, 141 male) patients with BD I | DSM-III-R, SID | No | Age at onset of BD | Age at first treatment |

| Schoeyen et al. (2011)34 | Inpatients and outpatients, Norway | 482 (268 female, 214 male) patients with BD I (315), BD II (140), and BD NOS (27) | DSM-IV, SCID | No | Age at first mood episode | Age at first treatment |

| Serretti et al. (2002)35 | Inpatients from Milan, Italy | 1004 (606 female, 398 male) patients with BD I (863) or BD II (141) | DSM-III, SADS | No | Age at onset of BD | Age at first treatment |

| Skjelstad et al. (2011)36 | Outpatients from southern Norway | 15 (11 female, 4 male) patients with BD II | DSM-IV, MINI | No | Age of first mood episode | Age at diagnosis |

| Slama et al. (2004)37 | Inpatients and outpatients from 2 clinics in Paris and Bordeaux, France | 307 (183 female, 124 male) patients with BD I (226) or BD II (81) | DSM-IV, DIGS | No | Age at first mood episode | Age at first treatment |

AAO, age of onset; BD, bipolar disorder; DIGS, Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies; DSM-III, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Third Edition; DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Third Edition, Revised; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition; DSM-IV-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Revised; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Text Revision; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NOS, not otherwise specified; RDC, Research Diagnostic Criteria; SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SID, Semistructured Interview for Depression.

aAge at first mood disturbance is considered equivalent to first symptoms.

Meta-Analysis

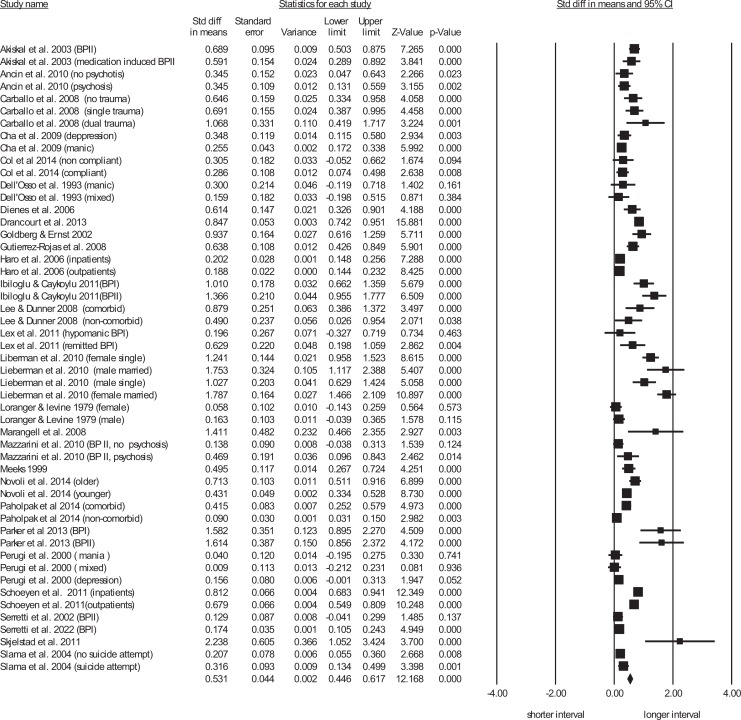

The pooled interval between the onset of BD and initial management was almost 6 years (5.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.8 to 6.8). There was very high between-sample heterogeneity (Figure 2, Suppl. Table S1). There was some evidence of publication bias towards samples that reported a longer interval (Egger’s regression, intercept = 3.18, t = 4.84, df = 49, P < 0.0001; Suppl. Figure S1). Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill analysis (6 studies trimmed to the right of mean and correction of point estimate to .46; 95% CI, .37 to .55) suggested publication bias had inflated the pooled effect size by 16%.

Figure 2.

Random effects meta-analysis of the interval between age at onset and age at management of bipolar disorders.

Differences in the definition of AOO made a significant contribution to between-sample heterogeneity. Samples reporting the AOO defined by the AOO of an episode of BD reported a longer interval between onset and initial management of BD than studies reporting first symptoms. Studies that reported the onset of symptoms had a longer interval between onset and management than studies that used less-well specified definitions of illness onset (Suppl. Table S1). Post hoc testing found significant differences between all 3 groups.

Differences in the definition of age at first management also made a significant contribution to between-sample heterogeneity. Studies reporting age at first diagnosis reported a longer interval than studies reporting first hospitalization. Studies reporting age at first hospitalization reported a longer interval than those recording age at first treatment (Suppl. Table S1). Post hoc testing found significant differences between all 3 groups.

The group of studies that used a defined method, such as a life chart approach, to ascertain the chronology of the onset of BD reported a longer interval between onset and management than studies that did not specify how the chronology was ascertained. A life chart is a systematic collection of retrospective and prospective data on the course of illness and its treatment recorded by a patient or a clinician that allows the monitoring of the illness course. Neither the method used to confirm the diagnosis nor overall reporting strength were found to have contributed to between-study heterogeneity (Suppl. Table S1).

Meta-regression found that samples with an earlier mean AOO had a longer interval between onset and management. Samples with a later mean age at initial management did not have a longer interval (Table 2). Studies with a higher proportion of BD I subjects tended to have a shorter interval between the onset of BD and management while more recently published studies reported a longer interval (Table 2). The proportion of males and the proportion of patients with substance or alcohol use disorder did not contribute to between-study heterogeneity.

Table 2.

Meta-Regression of Continuous Variables Potentially Associated with Between Sample Heterogeneity.

| Point Estimate | Standard Error | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Z Value | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at onset | –.05 | .006 | –.060 | –.036 | –7.92 | <0.001 |

| Mean age at initial management | –.004 | .008 | –.020 | .01 | –.50 | 0.61 |

| Proportion bipolar disorder Ia | –.005 | .001 | –.007 | –.002 | –4.27 | <0.001 |

| Proportion male | –.001 | .002 | –.005 | .003 | –.46 | 0.64 |

| Proportion with substance useb | .004 | .002 | –.001 | .009 | 1.53 | 0.12 |

| Year of publication | .02 | .005 | .01 | .03 | 3.84 | <0.001 |

aThirty-three samples.

bForty-eight samples.

Multiple meta-regression (Suppl. Table S2) model suggested that independent contributions to between-study heterogeneity (resulting in a longer period between onset and management) were made by samples that used a chronology method, used age at first diagnosis as the indicator of management, had a younger mean AOO, had fewer BD I patients, or were from more recently published studies. This model explained 63% of the observed between-study variance.

A second multiple meta-regression model was performed that excluded the use of AOO because of the potential circularity of this age as both an independent variable and as one of the ages defining the interval between onset and management. The second model confirmed the independent contribution of samples with a chronology method (Z = 3.34, P = 0.001), used first diagnosis to indicate initiation of management (Z = 3.87, P = 0.0001), had fewer BD I patients (Z = 2.97, P = 0.003), and were from more recent studies (Z = 2.59, P = 0.01) and explained 41% of the observed between-study variance.

Discussion

BD is a chronic and often debilitating psychiatric illness. Despite the availability of effective treatments, the delay between the onset and the initial management of BD is often very long, during which many patients experience distressing and disruptive symptoms. We calculated a pooled estimate of that interval, and examined aspects of the methodology of the included studies influencing the reported interval.

Our main finding was a pooled interval of almost 6 years between the onset of BD and its initial management. The marked between study variation in this interval was partly explained by the way in which onset was defined, how the chronology of onset was assessed, the average AOO, the proportion of patients with BD I, and when the study was published. A recent study38 found distinctive patterns of unfavorable illness characteristics related to the AOO comparing male and female subjects with bipolar disorder; however, in our study, gender did not significantly contribute to the variation of the interval between onset and initial management.

Our finding that the interval between onset and management was longer in studies that defined onset using the age at first episode, rather than the onset of symptoms, was surprising, because logically, the emergence of symptoms precedes the development of a full syndrome. A possible explanation is that the primary researchers sometimes defined the onset of BD symptoms by the onset of manic symptoms occurring in an initial manic episode, which emerged later than symptoms of depression. Moreover, clinicians may not recognize that an episode of depression is part of bipolar disorder.39

We also found that studies that used the age at diagnosis as the indicator of initial management had a longer interval than studies that used the onset of treatment or hospitalization. Although the multiple meta-regression suggested that the definition of the age of management was not independently associated with between-sample heterogeneity, the unadjusted result suggests that psychiatric treatment, including hospitalization, might precede diagnosis in BD. This can be readily understood in those patients who were admitted to the hospital for treatment of depression before the first manic episode. One recent study that examined subsyndromal manic symptoms in young people prior to the first manic episode found that almost all of the subjects had a gradual onset, with symptoms present for nearly a year.40 Only 20% of patients with BD who are experiencing a depressive episode are correctly diagnosed within the first year of seeking treatment,41 and clinicians are often unable to distinguish BD type I or II from unipolar depression.42

The use of identified methods such as the life chart method to independently establish chronology has predicted a greater interval between onset and management. This suggests that taking a more detailed history might identify an earlier AOO than a cross-sectional clinical interview; indeed, the life chart method has proven to be effective in detecting early signs and symptoms of BD both prospectively and retrospectively and may allow earlier diagnosis and treatment in some cases.43,44

Samples that had fewer BD I patients also reported a longer interval between onset and management. A possible explanation is that hypomanic episodes are frequently missed by clinicians, who may either fail to recognize the clinical presentation in a cross-sectional assessment or attribute it to other conditions18,45 such as personality disorder.

We found that studies with an earlier AOO of BD had a longer interval between onset and management. Although this might be a circular finding, in that a longer interval must be associated with either an earlier AOO or a later age at management, it might also be that signs and symptoms of BD are harder to detect among younger people, particularly adolescents. Our finding that a longer interval was not associated with a later mean age of initial management supports the latter interpretation, confirming the results in several other studies.19,46–48 In the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, a large survey of the prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in the United States, Wang and colleagues48 found that early onset disorders are consistently associated with longer delays in initial treatment. This may reflect the complexity of the clinical presentation of early onset cases and also the reluctance of clinicians to make a potentially stigmatizing diagnosis and recommending long-term care in young people.49 More recently published studies also reported a longer interval, which might be because contemporary researchers have greater awareness of the early AOO of other psychiatric disorders, from early intervention research in other conditions.

Clinical Implications

The main clinical implication is that even in research centres, there is an unacceptably long interval between the emergence of symptoms and the identification and treatment of bipolar disorder. The findings of this study identify an opportunity for intervention in the early stages of illness,50 which may in turn postpone or prevent the progression of BD. Currently, there are no biomarkers, such as genetic tests, brain imaging, or inflammatory markers, to help match nonspecific clinical presentations to the probability of developing the full syndrome of BD. However, recent clinical research to develop a staging model of BD that takes into consideration not only the history of the disorder, but also the heterogeneous manifestation of the condition, may improve our ability to detect BD earlier and also help develop guidelines for early intervention, including stage of illness-specific interventions.51,52

Some authors are already using the term duration of untreated bipolar disorder (DUB), defined as the interval between AOO of BD and age at first treatment with mood-stabilizing medication.18,53 Most of the published research on DUP refers to schizophreniform psychosis, and many DUP studies specifically exclude affective disorders, even those with psychotic symptoms.18 A recent meta-analysis3 of factors influencing DUP found that the mean DUP of the subgroup of patients with affective psychosis was about 4 months, far shorter than for nonaffective psychosis, which suggests that once the full syndrome of mania emerges, the delay in receiving diagnosis and treatment is comparatively short. Further research to identify factors associated with DUB could also help define the stages of illness.

The very long period between onset and management raises questions about the barriers to care for BD. From a patient perspective, there is often a lack of awareness of illness and a lack of willingness to commit to long-term prophylactic treatment of what is often a stigmatizing condition. There are also clinician-level barriers in the form of missed diagnosis from failing to adequately consider longitudinal or corroborative information and the reluctance of some clinicians to commit to a diagnosis and treatment of a chronic condition. There can also be service-level barriers to care when early symptoms are not especially disabling or life threatening and when patients have multiple presentations to uncoordinated services or to nonspecialist services. Another important implication of these findings is the clear need for more reliable methods of diagnosing BD during the early stages of the illness, including the use of a chronological assessment method such as the life chart method in clinical settings.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. The first limitation is that, from a very much larger number of studies initially selected, we were only able to include 27 studies from which we could make inferences about the interval between onset and management. Moreover, there was some evidence of publication bias among the studies we did locate, suggesting that if a larger number had reported the interval between onset and management, we might have found a shorter interval. Furthermore, the studies we examined were all retrospective, which are often hampered by recall bias and because researchers often have to rely only on the information given by the patients, without any corroborative information. The included studies were also from a limited number of mostly high-income countries and might not be representative of the global population of patients with BD.

A further limitation stems from the inclusive approach we took to the definitions of onset and the initiation of management. Some more recent studies attempted to establish the DUB, but future studies could be even more specific, for example, by reporting the interval between the onset of a manic syndrome and the initiation of treatment with mood-stabilizing medication.12 However, an analysis of the AOO of manic symptoms was not possible with the data currently available. In fact, for a large number of studies, it was not possible to determine whether “mood symptoms” (or even “mood episode”) was referring to manic/hypomanic or depressive symptoms (or episode), and for this reason, it was not possible to evaluate the differences related to the polarity and understand the role of initial depression in defining AOO and delay to diagnosis. More detailed information about the type of symptoms would allow more detailed analyses in future studies. Moreover, the studies selected for this meta-analysis employed different sources of information to determine AOO (12 studies used conducted interviews or administered questionnaires with the patients and/or with caregivers, 9 studies underwent a chart review or an analysis of clinical records, 8 studies used more than 1 method, and 12 studies did not specify how they determined the AOO). A more consistent and structured method to determine the onset of the disorder is therefore needed to obtain more precise results.

Finally, our study did not attempt to consider whether the long interval between onset and management that we found was mainly a result of the usual course of BD, with the onset of mood symptoms long before a potentially diagnosable BD syndrome, or was due to a real delay in treatment after the diagnosis of BD could have been made. This distinction is of practical importance because if the interval is mainly a delay between the onset of some symptoms and the disorder, then the focus of future research might be on identifying patterns of symptoms conferring a higher risk of subsequent mania, rather than on barriers to care once the syndrome is evident.

Conclusions

Meta-analysis of the available studies identified an interval of almost 6 years between the emergence of symptoms or episodes of BD and the initiation of any form of management. The very long delay between onset and treatment can have serious implications for patients, many of whom experience distress and face adverse consequences from erratic behavior arising from a potentially treatable condition. The identified interval presents an opportunity for earlier intervention through improved patient education, clinician training, and service delivery that might improve the outcome of the illness. The meta-analysis also identified significant methodological problems in the primary research, and the use of more consistent definitions in future research could allow a more accurate understanding of both the reasons for treatment delay and the nature of the illness itself. Future research should also focus on identifying features at onset that can predict a subsequent diagnosis and an unfavourable course of illness such as childhood maltreatment,54 which are essential for earlier identification and treatment. In the meantime, we hope the results of this meta-analysis will be considered ‘an approximate answer to the right question, which is often vague, than an exact answer to the wrong question’ (with apologies to the American statistician John Tukey).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: The online tables and figures are available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/0706743716656607.

References

- 1. Berk M, Berk L, Dodd S, et al. Stage managing bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Norman RM, Malla AK. Duration of untreated psychosis: a critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med. 2001;31(3):381–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Large M, Nielssen O, Slade T, et al. Measurement and reporting of the duration of untreated psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2(4):201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Penttila M, Jaaskelainen E, Hirvonen N, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(2):88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vieta E. Staging and psychosocial early intervention in bipolar disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(6):483–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Girolamo G, Dagani J, Purcell R, et al. Age of onset of mental disorders and use of mental health services: needs, opportunities and obstacles. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2012;21(1):47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connnell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 10. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akiskal HS, Hantouche EG, Allilaire JF, et al. Validating antidepressant-associated hypomania (bipolar III): a systematic comparison with spontaneous hypomania (bipolar II). J Affect Disord. 2003;73(1-2):65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ancin I, Santos JL, Teijeira C, et al. Sustained attention as a potential endophenotype for bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(3):235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carballo JJ, Harkavy-Friedman J, Burke AK, et al. Family history of suicidal behavior and early traumatic experiences: additive effect on suicidality and course of bipolar illness? J Affect Disord. 2008;109(1-2):57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cha B, Kim JH, Ha TH, et al. Polarity of the first episode and time to diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6(2):96–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Col SE, Caykoylu A, Karakas Ugurlu G, et al. Factors affecting treatment compliance in patients with bipolar I disorder during prophylaxis: a study from Turkey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(2):208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dell’Osso L, Akiskal HS, Freer P, et al. Psychotic and nonpsychotic bipolar mixed states: comparisons with manic and schizoaffective disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;243(2):75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dienes KA, Hammen C, Henry RM, et al. The stress sensitization hypothesis: understanding the course of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2006;95(1-3):43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drancourt N, Etain B, Lajnef M, et al. Duration of untreated bipolar disorder: missed opportunities on the long road to optimal treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(2):136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Features associated with the delayed initiation of mood stabilizers at illness onset in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(11):985–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gutierrez-Rojas L, Gurpegui M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, et al. Quality of life in bipolar disorder patients: a comparison with a general population sample. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(5):625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haro JM, van Os J, Vieta E, et al. Evidence for three distinct classes of ‘typical’, ‘psychotic’ and ‘dual’ mania: results from the EMBLEM study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(2):112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee JH, Dunner DL. The effect of anxiety disorder comorbidity on treatment resistant bipolar disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lex C, Hautzinger M, Meyer TD. Cognitive styles in hypomanic episodes of bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13(4):355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lieberman DZ, Massey SH, Goodwin FK. The role of gender in single vs married individuals with bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):380–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loranger AW, Levine PM. Age at onset of bipolar affective illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(11):1345–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marangell LB, Suppes T, Zboyan HA, et al. A 1-year pilot study of vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mazzarini L, Colom F, Pacchiarotti I, et al. Psychotic versus non-psychotic bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1-2):55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meeks S. Bipolar disorder in the latter half of life: symptom presentation, global functioning and age of onset. J Affect Disord. 1999;52(1-3):161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nivoli AM, Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, et al. Bipolar disorder in the elderly: a cohort study comparing older and younger patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(5):364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Okan Ibiloglu A, Caykoylu A. The comorbidity of anxiety disorders in bipolar I and bipolar II patients among Turkish population. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(5):661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paholpak S, Kongsakon R, Pattanakumjorn W, et al. Risk factors for an anxiety disorder comorbidity among Thai patients with bipolar disorder: results from the Thai Bipolar Disorder Registry. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:803–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parker G, Graham R, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Differentiation of bipolar I and II disorders by examining for differences in severity of manic/hypomanic symptoms and the presence or absence of psychosis during that phase. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):941–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Perugi G, Micheli C, Akiskal HS, et al. Polarity of the first episode, clinical characteristics, and course of manic depressive illness: a systematic retrospective investigation of 320 bipolar I patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2000;41(1):13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schoeyen HK, Vaaler AE, Auestad BH, et al. Despite clinical differences, bipolar disorder patients from acute wards and outpatient clinics have similar educational and disability levels compared to the general population. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(1-2):209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Serretti A, Mandelli L, Lattuada E, et al. Clinical and demographic features of mood disorder subtypes. Psychiatry Res. 2002;112(3):195–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skjelstad DV, Malt UF, Holte A. Symptoms and behaviors prior to the first major affective episode of bipolar II disorder: an exploratory study. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(3):333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Slama F, Bellivier F, Henry C, et al. Bipolar patients with suicidal behavior: toward the identification of a clinical subgroup. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1035–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holtzman JN, Miller S, Hooshmand F, et al. Gender by onset age interaction may characterize distinct phenotypic subgroups in bipolar patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;76:128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lloyd LC, Giaroli G, Taylor D, et al. Bipolar depression: clinically missed, pharmacologically mismanaged. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2011;1(5):153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Correll CU, Hauser M, Penzner JB, et al. Type and duration of subsyndromal symptoms in youth with bipolar I disorder prior to their first manic episode. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):478–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Baethge CJ, et al. Effects of treatment latency on response to maintenance treatment in manic-depressive disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(4):386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Phillips ML, Kupfer DJ. Bipolar disorder diagnosis: challenges and future directions. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1663–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Bendegem MA, van den Heuvel SC, Kramer LJ, et al. Attitudes of patients with bipolar disorder toward the life chart methodology: a phenomenological study. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2014;20(6):376–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Horn M, Scharer L, Walser S, et al. Comparison of long-term monitoring methods for bipolar affective disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;45(Suppl 1):27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Benazzi F. A prediction rule for diagnosing hypomania. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Altamura AC, Dell’Osso B, Berlin HA, et al. Duration of untreated illness and suicide in bipolar disorder: a naturalistic study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260(5):385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schaffer A, Cairney J, Cheung AH, et al. Use of treatment services and pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder in a general population-based mental health survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):386–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smith DJ, Ghaemi N. Is underdiagnosis the main pitfall when diagnosing bipolar disorder? Yes. BMJ. 2010;340: c854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vallarino M, Henry C, Etain B, et al. An evidence map of psychosocial interventions for the earliest stages of bipolar disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(6):548–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rios AC, Noto MN, Rizzo LB, et al. Early stages of bipolar disorder: characterization and strategies for early intervention. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2015;37(4):343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Duffy A. Toward a comprehensive clinical staging model for bipolar disorder: integrating the evidence. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):659–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Medeiros GC, Senco SB, Lafer B, et al. Association between duration of untreated bipolar disorder and clinical outcome: data from a Brazilian sample. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2016; 38(1):6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Agnew-Blais J, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment and unfavourable clinical outcomes in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016; 3(4):342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.