Abstract

Objectives:

The overarching aim of this article is to assess media portrayals of mental illness in Canada. We hypothesise that portrayals have improved over time, related to the various antistigma activities of organisations such as the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC). Specific objectives are to assess 1) overall tone and content of newspaper articles, 2) change over time, and 3) variables associated with positive or negative content.

Methods:

We collected newspaper articles from print and online editions of over 20 best-selling Canadian newspapers from 2005 to 2015 (N = 24,570) that mentioned key search terms such as mental illness or schizophrenia. These were read by research assistants, who assessed tone and content for each article using preassigned codes and categories. Data were subjected to chi-squared and trend analysis.

Results:

Over the study period, 21% of the articles had a positive tone and 28% had stigmatising content. Trend analysis suggested significantly improved coverage over 11 years (P < 0.001). For example, articles with a positive tone had almost doubled from 2005 (18.9%) to 2015 (34.8%), and articles with stigmatising content had reduced by a third (22.3% vs 32.7%). Analysis also suggested that articles on the front page, as well as articles in broadsheet newspapers, had significantly more positive coverage.

Conclusions:

The study indicates that news media coverage related to mental illness has improved over the past decade. This may be related to the concerted efforts of the MHCC, which has executed a targeted strategy aimed at reducing stigma and improving media coverage since 2007.

Keywords: media, newspapers, stigma, recovery, schizophrenia

Abstract

Objectifs:

Cet article visait principalement à évaluer la représentation dans les médias de la maladie mentale au Canada. Nous avons émis l’hypothèse que les représentations se sont améliorées avec le temps, en raison des diverses activités d’anti-stigmatisation menées par des organisations comme la Commission de la santé mentale du Canada (CSMC). Les objectifs spécifiques sont d’évaluer, 1) le ton général et le contenu des articles de journaux, 2) le changement au fil du temps, et 3) les variables associées au contenu positif ou négatif.

Méthodes:

Nous avons recueilli des articles de journaux publiés sur papier et en ligne dans plus de 20 journaux canadiens à fort tirage, de 2005 à 2015 (N = 24,570) qui mentionnaient les mots clés de recherche comme « maladie mentale » ou « schizophrénie ». Des assistants de recherche les ont lus, puis ont évalué le ton et le contenu de chaque article à l’aide de codes et de catégories pré-assignés. Les données ont fait l’objet d’une analyse chi-carré et des tendances.

Résultats:

Durant la période de l’étude, 21% des articles avaient un ton positif et 28% avaient un contenu stigmatisant. L’analyse des tendances suggérait une couverture significativement améliorée sur 11 ans (P < 0,001). Par exemple, les articles au ton positif avaient presque doublé de 2005 (18,9%) à 2015 (34,8%), et les articles au contenu stigmatisant avaient diminué d’un tiers (22,3% c. 32,7%). L’analyse suggérait également que les articles en première page, de même que les articles des journaux grand format, bénéficiaient d’une couverture significativement plus positive.

Conclusions:

L’étude indique que la couverture des médias d’information en matière de maladie mentale s’est améliorée au cours des 10 dernières années. Cela peut être lié aux efforts concertés de la CSMC, qui a exécuté une stratégie ciblée visant à réduire les stigmates et à améliorer la couverture des médias depuis 2007.

Evidence suggests that the general public use newspapers as a core source of information about mental illness.1,2 This includes print editions as well as online editions. Canadian surveys suggest that three-quarters of the adult population read at least 1 daily newspaper each week.3 In addition, online content is read and shared with increasing frequency, as newspapers make efforts to expand their digital platforms.4

Numerous studies have examined the portrayal of mental illness in the media. These include studies in the United States,5,6 New Zealand,2,7 Australia,8,9 the United Kingdom,10–12 and Canada.13–15 Study results converge on a set of consistent findings, regardless of time and place. Portrayals of people with a mental illness tend to revolve around negative factors such as danger, criminality, and violence and frequently contain stigmatising language. They rarely contain more positive or hopeful stories of recovery.16

For example, Thornicroft et al.12 examined over 3000 print newspaper portrayals of mental illness in the United Kingdom collected over a 4-year period, finding that 46% of the articles were stigmatising in content. Likewise, a recent Canadian analysis of over 10,000 articles from 2005 to 2010 found that around 40% of newspaper portrayals mentioning mental illness were in the context of crime and violence, while less than 20% mentioned recovery, treatment, or rehabilitation.15

These figures have concerned mental health advocates. Recent research suggests that negative portrayals can perpetuate stigma, social distance, and fear of people with mental illness. For example, Schomerus et al.17 examined public attitudes shortly after the (alleged) deliberate crashing of German-wings flight 9525 by a pilot with depression. They found a significant increase in public beliefs about unpredictability associated with mental illness, as well as a decrease in beliefs that people with mental illness are similar to the general population.

Likewise, American researchers found that negative attitudes towards people with mental illness increased in readers of a detailed news story about a mass shooting by a person with mental illness. Readers were significantly less likely to want to work with or live near someone with mental illness after reading the article.18 An Australian study found that participants who recalled negative media coverage of mental illness were significantly more likely to believe that people with mental illness are dangerous.19

This negative media coverage can contribute to a toxic social environment that facilitates the rejection, discrimination, stigmatisation, and marginalisation of people with a mental illness.20,21 These are barriers towards service utilisation, social participation, and recovery in people with mental illness.22–24

On the plus side, recent findings indicate that reading a positive article about recovery reduced stigma and increased affirming attitudes among readers.25 Likewise, an Australian study found more positive and hopeful articles about mental illness in some media, which was attributed to recent antistigma initiatives aimed at editors and journalists.8 Another study demonstrated that reporting of mental illness in a single Jamaican newspaper tended to be positive, which was attributed to local psychiatrists’ proactive engagement with this newspaper.26 In Canada, Stuart13 found that positive stories increased by a third and outweighed negative stories after a targeted media intervention, again to a single newspaper. These results have inspired advocates to extend collaboration with the media to improve coverage.

Numerous governments have formed national mental health commissions in recent years, including the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.27 The precise purpose of each commission varies but generally involves a mandate to promote recovery and reduce stigma. The Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) was formed in March 2007, with a 10-year mandate, and $15 million per year funding. In 2009, the MHCC created an antistigma initiative entitled ‘Opening Minds’, described as the “largest systematic effort to reduce the stigma of mental illness in Canadian history.”28 Opening Minds involves various antistigma activities, including intense and targeted interventions with the media.29,30

Interventions with the media include various efforts. Firstly, representatives from Opening Minds have visited major journalism schools in Canada to conduct seminars about the accurate reporting of mental health issues. Secondly, the MHCC has developed an online education course for actual and aspiring journalists, which is being used across the country. Thirdly, the MHCC funded the development of a set of guidelines (in collaboration with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Torture) to help journalists better report mental illness known as ‘Mindset’. These guidelines were made available as a PDF or as a short glossy booklet. Almost 4000 copies of ‘Mindset’ were sent to major newsrooms, including CBC, the Globe and Mail, and the Toronto Star in early 2014.

These combined activities could be considered a population-level intervention that may lead to improved media coverage of mental illness, which in turn may reduce stigma and discrimination in the general population. As such, the overarching aim of this article is to assess newspaper portrayals of mental illness in Canada. We hypothesise that portrayals have improved over time, which may be due to the combined activities of the MHCC. Specific objectives are to assess 1) overall tone and content of newspaper articles, 2) change over time, and 3) variables associated with positive content or negative content.

Methods

Design

The current article builds on a previous study we published in 2013 analysing newspaper representations of mental illness from 2005 to 2010. The current article uses the same methods but with an expanded data set from 2005 to 2015.15 Raw data consisted of individual newspaper articles collected on a daily basis over an 11-year period (1 January 2005 to 31 December 2015). We collected data from print and online editions of over 20 high-circulation Canadian newspapers, including the 2 best-selling national papers (the Globe and Mail and the National Post), as well as the best-selling regional papers from large cities such as the Toronto Star, the Vancouver Sun, and the Montreal Gazette. We did not collect data from purely online newspapers such as the Huffington Post, as these did not exist during the first half of the study.

Articles were retrieved using 2 media storage and retrieval software programs (FP Infomart and Newscan). We used these databases to scan and retrieve all articles appearing in any of our target newspapers that mentioned any of the following terms: mentally ill, mental illness, schizophrenic, and schizophrenia. These terms are the same as a previous seminal study of Canadian media, based on evidence suggesting schizophrenia is the most stigmatised mental disorder.13 Articles were excluded from the analysis if they only made a fleeting, unrelated, or metaphorical reference to mental illness, for example, mentioning a car crash near a mental hospital, talking about ‘schizophrenic’ weather, or discussing share prices for psychiatric medication.

Procedures

A detailed description of variables and coding methods has been published elsewhere.15,31,32 In short, a highly trained graduate-level research assistant read each article (one reader per article), assigning each article a series of codes (defined a priori at study outset) based on answers to numerous questions. Relevant questions for this study are 1) date of story; 2) form of newspaper (tabloid, broadsheet, or online); 3) placing (front page or inside pages); 4) “Is the overall tone optimistic/positive about mental health?” (yes, no, neutral); 5) “Is recovery/rehabilitation a major theme?” (yes, no, neutral); 6) “Is the story stigmatising in tone and/or content?” (yes, no, neutral); 7) “Is danger, violence, or criminality linked negatively to mental illness?” (yes, no, neutral); 8) “Is shortage of resources or poor quality of care a theme?” (yes, no, neutral); 9) “Are mental health experts/people with mental illness quoted in the text either directly or paraphrased?” (not quoted, quoted positively, quoted negatively, quoted mixed); and 10) “Are mental health interventions (e.g., medicine or therapy) discussed in the story?” (not discussed, discussed positively, discussed negatively, discussed mixed). Codes were entered into Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), which was used for primary data storage. This was exported to STATA (version 11; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS (version 19; SPSS, Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, IL, USA) for analysis.

Training for research assistants involved induction workshops, reading seminal studies on recovery and stigma, supervised practice coding, close monitoring by the first author, and utilisation of a workbook that gave model answers to preexisting newspaper articles. For example, research assistants were instructed to code an article with a ‘positive tone’ if the article discussed mental illness constructively (e.g., talking about societal contributions made by people with mental illness or promising new initiatives).

Interrater reliability scores were calculated for coders, based on a subsample of the data. We computed Fleiss’s kappa33 for the core questions described above. Early in the project, kappa statistics indicated reasonable agreement on average. This led the first author to hold additional meetings and trainings to clarify concepts and recoding of categories to improve agreement. After these interventions, kappa scores ranged from 0.68 to 0.83, indicating substantial agreement across raters.

Analysis

Frequency counts and proportions were produced for each measure. Line charts and trend analysis were used to explore change over time among the core questions. Trend analysis was based on a linear regression, and the scatterplot was used to confirm the linear pattern, using the PTrend function in STATA (version 11). For the purposes of this study, we are considering the MHCC as an antistigma population intervention in and of itself. This approach allows us to explore the impact of the MHCC on media representations of mental illness. As such, we conducted the chi-square test to compare differences in tone and content before and after the launch of MHCC (March 2007). Given our interest in variables that might be linked to positive or negative coverage of mental illness, we also used the chi-square test to compare articles appearing in tabloid, broadsheet, or online, as well as articles that appeared on the front page compared to the inside pages. Significance levels were set as P < 0.05 with 2 tails.

Results

The basic description is presented in Table 1. Just under 25,000 articles were coded. There was a steady increase in the number of articles over the years, with the total number of articles for the last year of the study being over double that of the first year of the study (2924 in 2015 vs 1405 in 2005). There has also been a massive rise in online content, with this making up over 50% of the articles in the last year of the study, while in 2005 it was only 3%.

Table 1.

Basic Description of Newspaper Measurements (2005 to 2015; N = 24,570).

| Year | Total (N) | Form of Newspaper | Front Page (%) | Positive Tone (%) | Recovery as a Theme (%) | Stigmatising in Content (%) | Danger Linked Negatively to Mental Illness (%) | Shortage of Resource as a Theme (%) | Expert Quoted (%) | PWMI Quoted (%) | Intervention Discussed (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tabloid (%) | Broadsheet (%) | Online (%) | |||||||||||

| 2005 | 1405 | 27.4 | 69.6 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 18.9 | 11.2 | 32.7 | 42.3 | 12.0 | 27.7 | 22.4 | 21.2 |

| 2006 | 1558 | 19.6 | 73.7 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 35.8 | 31.3 | 16.2 | 20.8 | 13.2 | 13.7 |

| 2007 | 1910 | 13.4 | 74.5 | 12.2 | 5.7 | 12.7 | 10.8 | 27.4 | 25.1 | 21.9 | 17.3 | 12.6 | 14.8 |

| 2008 | 2237 | 12.4 | 67.5 | 20.1 | 0.1 | 9.7 | 27.8 | 15.0 | 50.4 | 55.6 | 32.2 | 17.7 | 23.1 |

| 2009 | 1947 | 10.4 | 65.8 | 23.8 | 0.2 | 8.2 | 16.4 | 35.7 | 38.3 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 15.2 | 18.6 |

| 2010 | 2208 | 13.0 | 57.5 | 29.6 | 3.0 | 14.4 | 23.6 | 39.7 | 49.2 | 30.9 | 27.1 | 20.9 | 20.3 |

| 2011 | 2018 | 10.2 | 55.9 | 33.8 | 4.4 | 19.5 | 17.6 | 26.6 | 44.4 | 31.9 | 31.4 | 24.4 | 21.2 |

| 2012 | 2205 | 7.7 | 55.3 | 37.1 | 1.5 | 32.2 | 15.6 | 24.4 | 52.8 | 31.3 | 22.8 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| 2013 | 2812 | 7.2 | 44.2 | 48.5 | 3.0 | 25.8 | 10.5 | 19.7 | 57.9 | 26.9 | 27.5 | 20.8 | 18.8 |

| 2014 | 3346 | 6.7 | 39.6 | 53.7 | 3.2 | 25.4 | 10.5 | 34.2 | 55.1 | 32.1 | 29.6 | 21.0 | 23.1 |

| 2015 | 2924 | 7.9 | 36.9 | 55.2 | 3.2 | 34.8 | 9.8 | 22.3 | 50.9 | 32.1 | 26.4 | 23.7 | 25.8 |

| Average | 2234 | 11.2 | 55.4 | 33.5 | 2.4 | 20.9 | 15.0 | 28.0 | 47.0 | 29.8 | 26.4 | 19.6 | 20.5 |

PWMI, people with mental illness.

Overall proportions from the 11 years of the study indicate that negatively or neutrally oriented articles tend to outweigh positively focused ones. For example, almost half linked danger, violence, or criminality to mental illness. Only 21% of articles had an overall positive tone, only 15% had rehabilitation or recovery as a theme, only 20% quoted people with mental illness in the text, and only 21% discussed mental health interventions.

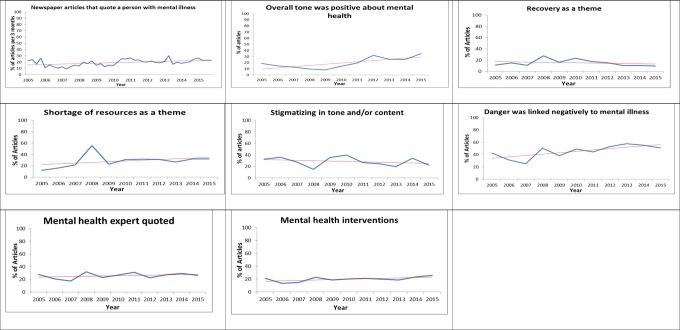

The trend analysis indicated significant change over the 11-year period for various measurements (see Table 2 and Figure 1) supporting the hypothesis for improved coverage. Most notably, we found a significant increasing trend over time in articles that 1) had a positive tone, 2) discussed shortage of resources, 3) quoted an expert about mental illness, 4) quoted people with mental illness, or 5) discussed mental health interventions (all at P < 0.001). Likewise, we noted a significant decreasing trend in articles that were stigmatising in tone and content (all at P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Trend Analysis of Newspaper Measurements over 11 Years.

| Newspaper Measurements | Slopea | z | P for Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive tone (%) | 0.022 | 26.498 | <0.001 |

| Recovery as a theme (%) | –0.007 | 10.171 | <0.001 |

| Stigmatising in content (%) | –0.005 | 5.640 | <0.001 |

| Danger linked negatively to mental illness (%) | 0.022 | 21.983 | <0.001 |

| Shortage of resource as a theme (%) | 0.009 | 9.133 | <0.001 |

| Mental health expert quoted (%) | 0.004 | 4.889 | <0.001 |

| PWMI quoted (%) | 0.007 | 9.108 | <0.001 |

| Intervention discussed (%) | 0.007 | 8.040 | <0.001 |

PWMI, people with mental illness.

aA slope of >0 indicates an increasing trend, while a slope of <0 indicating a decreasing trend. The larger the value is, the more degree of slope for the trend line.

Figure 1.

Trend lines for key newspaper measurements over time (2005 to 2015).

The comparison of newspaper articles before and after the launch of the MHCC (March 2007) is presented in Table 3. Taken in the round, these data support the hypothesis that newspaper coverage has significantly improved since the formation of the MHCC. For example, newspaper articles published after March 2007 had significantly different proportions of 1) having an overall positive tone (17.1% before vs 21.5% after), 2) having a stigmatising tone or content (34% before vs 27% after), 3) having shortage of resource as a theme (15.8% before vs 32.0% after), 4) quoting mental health experts (23.2% before vs 26.9% after), 5) quoting people with mental illness (17.0% before vs 20.1% after), and 6) discussing mental health interventions (16.7% before vs 21.2%). All these differences were P < 0.001.

Table 3.

Comparison of Newspaper Measurements Before and After the Launch of MHCC (2007 March).

| Newspaper Measurements | Before MHCC (n = 3374) | After MHCC (n = 21,196) | Chi-Square | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive tone (%) | 17.1 | 21.5 | 40.6 | <0.001 |

| Recovery as a theme (%) | 14.0 | 15.2 | 4.3 | 0.116 |

| Stigmatising in content (%) | 34.0 | 27.0 | 573.6 | <0.001 |

| Danger linked negatively to mental health (%) | 35.1 | 48.9 | 225.8 | <0.001 |

| Shortage of resource as a theme (%) | 15.8 | 32.0 | 438.0 | <0.001 |

| Expert quoted (%) | 23.2 | 26.9 | 20.5 | <0.001 |

| PWMI quoted (%) | 17.0 | 20.1 | 25.9 | <0.001 |

| Intervention discussed (%) | 16.7 | 21.2 | 94.1 | <0.001 |

MHCC, Mental Health Commission of Canada; PWMI, people with mental illness.

Two variables in both the trend analysis and the chi-squared tests are inconsistent with the hypothesis of improved coverage. Both these analyses suggest a significant increase in articles that link mental illness to crime and violence, and neither analysis indicates that the proportion of articles about recovery and rehabilitation is increasing. In fact, the trend analysis indicates a decrease in articles about recovery.

As can be seen in Table 4, articles in tabloid newspapers tended to have the most negatively oriented coverage, whereas articles in broadsheets and online tended to be much more positively oriented. Articles in tabloid newspapers had the highest proportions of having a stigmatising tone (34.7%) and linking danger negatively to mental illness (53.1%). Articles in broadsheet newspapers had the highest proportions of 1) having recovery as a theme (18.0%), 2) having shortage of resource as a theme (31.5%), and 3) quoting mental health experts (27.4%). Online articles had the highest proportion of 1) positive tone (23.8%), 2) quoting people with mental illness (19.9%), and 3) discussing mental health interventions (21.2%). All these differences were significant at the P < 0.001 level.

Table 4.

Comparison of Newspaper Measurements between Forms of Newspaper.

| Newspaper Measurements | Forms of Newspaper | Chi-Square | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tabloid (n = 2473) | Broadsheet (n = 13,606) | Online (n = 8221) | |||

| Positive tone (%) | 12.1 | 20.9 | 23.8 | 188.5 | <0.001 |

| Recovery as a theme (%) | 8.6 | 18.0 | 12.3 | 357.0 | <0.001 |

| Stigmatising in content (%) | 34.7 | 28.0 | 25.7 | 456.6 | <0.001 |

| Danger linked negatively to mental health (%) | 53.1 | 42.7 | 52.0 | 313.4 | <0.001 |

| Shortage of resource as a theme (%) | 20.3 | 31.5 | 30.1 | 183.5 | <0.001 |

| Expert quoted (%) | 19.4 | 27.4 | 27.0 | 162.3 | <0.001 |

| PWMI quoted (%) | 18.2 | 19.8 | 19.9 | 66.5 | <0.001 |

| Intervention discussed (%) | 16.5 | 21.0 | 21.2 | 51.7 | <0.001 |

MHCC, Mental Health Commission of Canada; PWMI, people with mental illness.

As can be seen in Table 5, articles on the front page tended to be much more positively oriented than articles on the inside pages. Articles on the front page had a significantly higher proportion of 1) positive overall tone (25.5% vs 20.9%; P < 0.001), 2) recovery as a theme (17.8% vs 15.1%; P < 0.001), 3) shortage of resources as a theme (40.7% vs 29.7%; P < 0.001), 4) quoting mental health experts (31.7% vs 26.2%; P = 0.010), 5) quoting people with mental illness (21.7% vs 19.7%; P = 0.012), and 6) discussing mental health interventions (28.4% vs 20.4%; P < 0.001). Front-page articles also had significantly lower proportions of articles that were stigmatising in tone (22.1% vs 28.0; P = 0.003) and linking danger negatively to mental health (35.8% vs 47.3%; P < 0.001).

Table 5.

Comparison of Newspaper Measurements between Placing of Articles in the Newspaper.

| Newspaper Measurements | Placing of Articles | Chi-Square | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front Page (n = 589) | Inside Pages (n = 23,590) | |||

| Positive tone (%) | 25.5 | 20.9 | 24.0 | <0.001 |

| Recovery as a theme (%) | 17.8 | 15.1 | 20.6 | <0.001 |

| Stigmatising in content (%) | 22.1 | 28.0 | 11.9 | 0.003 |

| Danger linked negatively to mental health (%) | 35.8 | 47.3 | 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Shortage of resource as a theme (%) | 40.7 | 29.7 | 33.4 | <0.001 |

| Expert quoted (%) | 31.7 | 26.2 | 11.4 | 0.010 |

| PWMI quoted (%) | 21.7 | 19.7 | 11.0 | 0.012 |

| Intervention discussed (%) | 28.4 | 20.4 | 24.1 | <0.001 |

MHCC, Mental Health Commission of Canada; PWMI, people with mental illness.

Discussion

The key finding of the study is that newspaper coverage of mental illness has significantly improved from January 2005 to December 2015. Articles published more recently were significantly more likely to have a positive tone, to mention shortage of resources, to quote people with mental illness or mental health experts, and to be less stigmatising in content. Likewise, articles published since the formation of the MHCC (March 2007) were significantly more likely to be more positively oriented and less stigmatising than articles published pre-MHCC. As such, the study results support the hypothesis that newspaper coverage of mental illness is improving.

This improvement is welcome news given the concerted efforts made by the MHCC to raise awareness and reduce stigma.29 In particular, the MHCC ‘Opening Minds’ antistigma initiative has made targeted efforts to educate journalists about mental illness, as discussed comprehensively earlier.30 The MHCC is not the only organisation in Canada attempting to reduce stigma and raise awareness. Numerous other educational and antistigma campaigns have occurred, which have increased in intensity in the past decade. These include 1) large-scale initiatives such as Bell Let’s Talk, Movember, and Provincial government interventions; 2) smaller bottom-up campaigns located in schools, universities, workplaces, and other community-based organisations; and 3) the continued efforts of mental health organisations such as the Canadian Mental Health Association, the Schizophrenia Society of Canada, Mood Disorders Canada, and the Canadian Psychiatric Association.

One interpretation of the results is that the amassed efforts of all these organisations, but most particularly the MHCC, contributes towards the improvements in media coverage. This may also explain the increase in articles about mental illness per se, with the 2015 total being over double that of the 2005 total. This suggests that stable, well-funded, and dynamic national mental health commissions may catalyse positive change on the ground. The results support the contention that these commissions could be considered a successful form of population intervention that could be implemented elsewhere.

Two variables measured did not improve. This was the measurement of recovery as a theme as well as the measurement of linkage between crime/violence and mental illness. In fact, articles about crime and violence related to mental illness increased, averaging over 50% of articles in the last 5 years of the study. This 50% figure overlaps with other studies elsewhere.1,2,7,8,16 This is worrying given that recent research indicates that these articles can increase fear, social distance, and beliefs about dangerousness.17–19 Further qualitative analysis of our data has indicated that articles about crime and violence are not always stigmatising but can report events of public interest in a nuanced and balanced manner, although these remain the minority.34 This high proportion may be a consequence of a newspaper industry that still considers crime reporting as an essential part of a daily newspaper.35

The rise in articles about crime also overlapped with the 41st Canadian Parliament (2011-2015), with a Conservative majority for the first time since 1988. A core government priority throughout these years was improving public safety and reducing crime, including Bills C2, C10, C14, C19, C30, and C54. All of these inspired much public debate and some controversy. Much of this debate was centred on the legal concept of ‘not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder’, which the government was trying to amend. This may account for the rise in articles about crime and violence related to mental illness, which may have crowded out stories about recovery and rehabilitation.

Another key finding of the study is that articles on the front page and articles published in broadsheet newspapers (as opposed to tabloids) were more positive. For example, broadsheets had over double the amount of articles focused on recovery compared to tabloids, and front-page articles were significantly less likely to be about crime and violence. The finding regarding the front page is somewhat surprising, given that a popular media slogan is ‘if it bleeds it leads’.35 Again this finding represents welcome news and suggests media destigmatisation efforts may be having an impact. The finding regarding broadsheets and tabloids is less surprising, given tabloids’ reputation for salacious news coverage. This finding is also somewhat worrying given that tabloids have a wider readership than broadsheets.36

While the results indicate significant progress in the reporting of mental illness over time, overall proportions remain open for improvement. For example, in the last year of the study (2015), 35% of the articles had a positive tone, while 22% had a stigmatising content. These figures are significantly improved in comparison to those found in 2005, which gives some comfort. These figures are also better than a similar British study, which found that 45% of articles about mental illness were stigmatising in 2011.12 That said, continued campaigns and efforts could help change tone and content even further.

The results suggest specific areas to target. For example, tabloid publications appear to have the most negatively oriented coverage of mental illness; newsrooms therein may benefit from specific trainings and interventions. Similarly, crime and court reporters could be singled out for further education in mental health issues given that over half of the articles in recent years centre on crime and violence. Finally, positive stories of recovery and rehabilitation continue to be underrepresented. This is concerning given that research suggests these stories are the most successful at reducing stigma and increasing affirming attitudes.25 As such, editors and journalists could be encouraged to write about local or prominent individuals in recovery. Community psychiatrists and mental health advocacy organisations could take a lead in this regard, contacting local newspapers to raise awareness about recovery realities.

The study has numerous limitations. We focused on traditional well-established newspapers given that this was the mainstay of the media at the start of the study in 2005. Since then, social media such as YouTube and Facebook, as well as online news aggregators such as the Huffington Post and Buzzfeed, have expanded exponentially. Many Canadians now use these sites to obtain news and information, but these were not part of the present study. Furthermore, this article focused on newspapers and did not assess television or radio representations of mental illness. However, these deficits will be addressed by recently initiated substudies examining television and social media representation of mental illness. Finally, and perhaps most important, the ecological design does not allow us to draw firm conclusions about cause and effect. This was not an experimental study, and we did not compare newspapers with or without exposure to the MHCC. The interpretation that the improved coverage is due to MHCC activities is plausible, but improvement may be due to unmeasured factors or part of wider secular trends.

Conclusion

The study indicates that news media coverage related to mental illness in Canada has improved significantly over the past decade. One interpretation of the results is that this improvement is related to the concerted efforts of the MHCC, especially its targeted strategy of educating and informing newsrooms and journalists. Study results indicate that there is still room for improvement and need for continued work with journalists and newsrooms. This may best be targeted at tabloid newspapers and crime journalists, with an emphasis on recovery.

Acknowledgements

We thank the MHCC, especially Mike Pietrus and Romie Christie, for ongoing support.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the Mental Health Commission of Canada, which is funded by Health Canada.

References

- 1. Wahl OF. Mass media images of mental illness: a review of the literature. J Community Psychiatry. 1992;20:343–352. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coverdale J, Nairn R, Claasen D. Depictions of mental illness in print media: a prospective national sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36:697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newspaper Audience Database, Inc. Readership of Canadian daily newspapers remains strong [Internet] [cited 2016 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.nadbank.com/en/system/files/2008%20NADbank%20Study%20Readership%20Press%20Release-English_0.pdf

- 4. Greer JD, Yan Y. Newspapers connect with readers through multiple digital tools. Newspaper Res J. 2011;32(4):83–97. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Gracia G, et al. Newspaper stories as measures of structural stigma. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wahl OF, Wood A, Richards R. Newspaper coverage of mental illness, is it changing? Psychiatr Rehab Skills. 2002;6:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nairn RG, Coverdale JH. People never see us living well: an appraisal of the personal stories about mental illness in a prospective print media sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Francis C, Pirkis J, Blood RW, et al. The portrayal of mental health and illness in Australian non-fiction media. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rowe R, Tilbury F, Rapley M, et al. ‘About a year before the breakdown I was having symptoms’: sadness, pathology and the Australian newspaper media. Sociol Health Illn. 2003;25:680–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anderson M. ‘One flew over the psychiatric unit’: mental illness and the media. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2003;10:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stark C, Paterson B, Devlin B. Newspaper coverage of a violent assault by a mentally ill person. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2004;11:635–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thornicroft A, Goulden R, Shefer G, et al. Newspaper coverage of mental illness in England 2008-2011. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(Suppl 55):S64–S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stuart H. Stigma and the daily news: evaluation of a newspaper intervention. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olstead R. Contesting the text: Canadian media depictions of the conflation of mental illness and criminality. Sociol Health Illn. 2002;24:621–643. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whitley R, Berry S. Trends in newspaper coverage of mental illness in Canada: 2005-2010. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;47(7):609–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ward G. Mental health and the national press. London: Health Education Authority; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schomerus G, Stolzenburg S, Angermeyer MC. Impact of the Germanwings plane crash on mental illness stigma: results from two population surveys in Germany before and after the incident. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):362–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Effects of news media messages about mass shootings on attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and public support for gun control policies. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(5):494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reavley NJ, Jorm AF, Morgan AJ. Beliefs about dangerousness of people with mental health problems: the role of media reports and personal exposure to threat or harm. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(9):1257–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, et al. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dinos S, Stevens S, Serfaty M, et al. Stigma: the feelings and experiences of 46 people with mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thornicroft G. Shunned. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rusch N, Thornicroft G. Does stigma impair prevention of mental disorders? Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Whitley R. Ethno-racial variation in recovery from severe mental illness: a qualitative comparison. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:340–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corrigan PW, Powell KJ, Michaels PJ. The effects of news stories on the stigma of mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Whitley R, Hickling F. Open papers, open minds? Media representations of psychiatric deinstitutionalization in Jamaica. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2007;44:659–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosen A, Goldbloom D, McGeorge P. Mental health commissions: making the critical difference to development and reform of mental health services. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(6):593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Opening Minds interim report. Ottawa, Canada: Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stuart H, Chen SP, Christie R, et al. Opening minds in Canada: background and rationale. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:S8–S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stuart H, Chen SP, Christie R, et al. Opening minds in Canada: targeting change. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:S13–S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Whitley R, Berry S. Analyzing media representations of mental illness: lessons learnt from a national project. J Ment Health. 2013;22(3):246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Whitley R, Adeponle A, Miller AR. Comparing gendered and generic representation of mental illness in Canadian newspapers: an exploration of the chivalry hypothesis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull. 1971;76:378–383. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berry S, Whitley R. Stigmatizing representations: criminality, violence, and mental illness in Canadian mainstream media. In: Smith Fullerton R, Richardson C, editors. Covering Canadian crimes: what journalists should know and the public should question Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2016:346–365. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith Fullerton R, Richardson C, editors. Covering Canadian crimes: what journalists should know and the public should question. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nadkarni M. Tabloid vs. broadsheet [Internet] [cited 2016 Jun 3]. Available from: http://en.ejo.ch/ethics-quality/tabloid-vs-broadsheet