Abstract

Background:

Although anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is generally regarded as a successful procedure, only 65% of patients return to their preinjury sport. While return-to-sport rates are likely higher in younger patients, there is a paucity of data that focus on the younger patient and their return-to-sport experience after ACL reconstruction.

Purpose:

To investigate a range of return-to-sport outcomes in younger athletes who had undergone ACL reconstruction surgery.

Study Design:

Case series; Level of evidence, 4.

Methods:

A group of 140 young patients (<20 years old at surgery) who had 1 ACL reconstruction and no subsequent ACL injuries completed a survey regarding details of their sport participation at a mean follow-up of 5 years (range, 3-7 years).

Results:

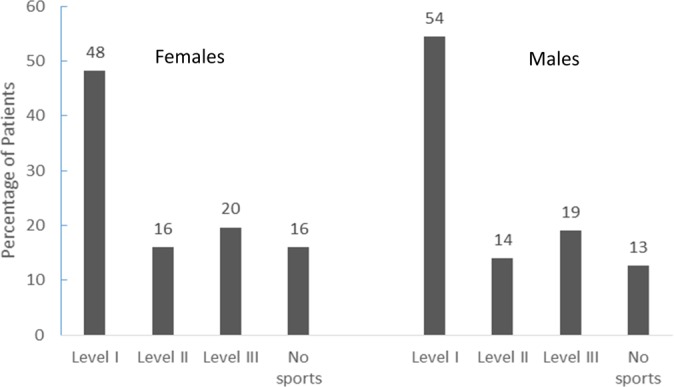

Overall, 76% (95% CI, 69%-83%) of the young patient group returned to the same preinjury sport. Return rates were higher for males than females (81% vs 71%, respectively; P > .05). Of those who returned to their sport, 65% reported that they could perform as well as before the ACL injury and 66% were still currently participating in their respective sport. Young athletes who never returned to sport cited fear of a new injury (37%) or study/work commitments (30%) as the primary reasons for dropout. For those who had successfully returned to their preinjury sport but subsequently stopped participating, the most common reason cited for stopping was study/work commitments (53%). At a mean 5-year follow-up, 48% of female patients were still participating in level I (jumping, hard pivoting) sports, as were 54% of males.

Conclusion:

A high percentage of younger patients return to their preinjury sport after ACL reconstruction surgery. For patients in this cohort who had not sustained a second ACL injury, the majority continue to participate and are satisfied with their performance.

Keywords: ACL, young athlete, sport performance, sport participation, fear of reinjury

Return to sport represents an important outcome benchmark after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. However, results of a recent meta-analysis show that only 65% of patients return to their preinjury level of sport.3 In the same review, it was suggested that younger patients are more likely to return to their preinjury sport. Results show that patients who had returned were on average 3 years younger than those who had not returned.3

Mascarenhas et al9 examined return-to-sport outcomes in a group of young athletes (<25 years old) and reported that although 72% were able to participate in very strenuous or strenuous sporting activities after surgery, only half were able to return to their preinjury participation levels.

A subsequent study by Webster et al16 reported that 88% of younger patients (<20 years old at surgery) returned to strenuous sports compared with a much lower 53% return rate for those older than 20 years at surgery, but the study did not specifically document return to preinjury sport. A more recent study by Morgan et al10 showed that 69% of their young patient cohort (<18 years old at surgery) were able to return to preinjury level of sport. Overall, there are limited data available that specifically focus on return-to-sport rates in the younger ACL-reconstructed athlete, and the existing results are mixed.

In addition to reporting return-to-sport rates, it is relevant to understand the return-to-sport experience from the patient perspective. In this regard, it may be useful to understand how the patient feels about their performance and the reasons why they might discontinue participation or even fail to return to their preinjury sport. It is important to recognize that both knee- and non–knee-related factors influence the return-to-sport experience, and it is often the non–knee-related factors that are more difficult to quantify. One way to be able to better understand non–knee-related factors is to survey patients who have had successful surgery without further ACL injuries. The focus of this study was therefore to investigate a range of return-to-sport outcomes in younger athletes who had undergone ACL reconstruction without further ACL injury.

Methods

Patients who had undergone a primary autograft hamstring ACL reconstruction were identified from the consecutive surgical lists of 2 surgeons between July 2008 and June 2012. Inclusion criteria were patients younger than 20 years at the time of surgery and having their first ACL reconstruction procedure. Patients were excluded if they had previous ACL injury or surgery to the contralateral knee. After institutional ethics approval, all eligible patients (n = 316) were contacted for inclusion in the current study. At the time of follow-up, all patients were a minimum 3 years post–primary reconstruction surgery.

Eligible patients were asked to complete a detailed sports activity survey to determine the primary sport they had participated in prior to their ACL injury and whether they had returned to that sport after the reconstruction surgery. Also included were questions regarding sport performance and reasons for discontinuing sport participation. For performance, patients who had returned to their preinjury sport were asked whether they “felt as though they could play (or perform) as well as before their ACL injury” (yes or no response). Patients completed a sport participation profile, which required them to report all sports they had participated in and the frequency of participation during the past 12 months. For participation frequency, the response options were 4 to 7 days per week, 1 to 3 days per week, 1 to 3 times per month, and less than 12 times per 12 months. Patients also indicated whether their ACL injury involved contact with another player or object (contact mechanism) or not (noncontact) and provided a single assessment numeric estimation (SANE score) of their current knee function.

The survey was initially in an online format, and patients were contacted via phone to confirm eligibility and sent a message (via SMS or email) that directed them to a link to the survey. The survey was administered using Survey Monkey software (SurveyMonkey Inc). People who did not respond were subsequently contacted by telephone and a follow-up letter in the mail. All patients who received mail contact were sent paper copies of the survey and a prepaid return envelope.

Statistics

Return-to-sport rates were calculated and presented as percentages (with 95% CIs). Contingency tables were used to determine whether returning to sport differed with sex or rating of performance (rated same vs rated worse). Descriptive statistics were calculated for discontinuing sport participation responses and for sport participation profiles.

Results

Of the 316 eligible patients, 237 initially participated (75%). Of these, 97 had sustained a further ACL injury and, as directed, did not complete the full survey after indicating that they had experienced a further ACL injury. There were 79 patients who decided not to participate or whom we were unable to contact. The full survey was completed by 140 patients who participated at a mean follow-up time of 5.1 years (range, 3-7 years). There were 82 males and 58 females with a mean age of 17.2 years (SD, 1.3 years) at primary ACL reconstruction surgery and 22.3 years (SD, 1.3 years) at the time of participation in the study. All patients were involved in level I or II sports11 prior to their ACL injury, with the most common preinjury sports being Australian Rules football, netball, soccer, and basketball (together accounting for 80% of preinjury sports played by the cohort). Eighty-two percent of the primary ACL injuries occurred in a noncontact situation. The mean time between ACL injury and surgery was 12 weeks, and all patients had ACL reconstruction within 1 year of injury (range, 1-45 weeks).

Overall, 107 (76%; 95% CI, 69%-83%) young patients had returned to their preinjury sport. The return-to-sport rate was higher in males (81%; 95% CI, 71%-88%) compared with females (71%; 95% CI, 58%-81%) but not statistically different (P = .1). Of the 107 who returned, 70 patients (65%; 95%CI, 56%-75%) reported that they felt as though they could perform as well as before their injury. At the time of completing the survey 71 of the 107 (66%; 95% CI, 57%-75%) who had returned were still participating in their preinjury sport. Those who rated their performance as the same as before their injury were more likely to still be participating compared with those who did not feel that they could perform as well (70% vs 59%, respectively; P = .27), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Patients who had returned but subsequently ceased participating in their preinjury sport reported study/work commitments as the most common reason for discontinuation, and patients who never returned to sport reported fear of a new injury as the most common reason for never returning (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Reasons Given by Younger Patients Who Ceased or Never Returned to Preinjury Sport Participation After ACL Reconstructiona

| Patients, % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Reasons for stopping preinjury sport participation (n = 36) | |

| Work/study commitments | 53 (19) |

| Physical problems | 17 (6) |

| Fear of a new injury | 14 (5) |

| Other injury | 8 (3) |

| Travel | 8 (3) |

| Reasons for never returning (n = 33) | |

| Fear of a new injury | 37 (12) |

| Work/study commitments | 30 (10) |

| Physical problems | 21 (7) |

| Travel | 12 (4) |

aACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

Figure 1 shows the sport participation profiles of the cohort. Data include the percentage of patients who were participating in level I (jumping, hard pivoting), level II (running, twisting), level III (no turning or jumping), or no sports on a weekly basis for the preceding 12-month period and show that overall, half of patients were regularly participating in level I sports and that only 15% of the young patient cohort were not participating in any sport at all. The mean SANE score was 87.5 (median, 90; SD, 16).

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients participating in sports by level of activity on a weekly basis for the preceding 12-month period. Level I, jumping, hard pivoting; level II, running, twisting; level III, no turning or jumping.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate a 76% return to preinjury sport rate for younger ACL-reconstructed patients who have not had a second ACL injury. The return-to-sport rate reported in the current investigation is slightly greater than those reported in 2 previous studies of similar younger patient cohorts (69%10 and 57%9) but lower than that of an “elite” college level cohort in which the return rate was 88%.6 A recent systematic review of younger patients (<18 years at surgery) reported return rates between 78% and 100% for acute ACL-reconstructed patients and between 84% and 100% after delayed reconstructions.4 However, it is worth noting that most of the studies included in this review had small patient numbers, with only 1 study having a cohort of more than 100 patients and the majority having fewer than 50 patients. Nonetheless, the current findings combined with previous data suggest that a high proportion of younger athletes return to their preinjury sport after ACL reconstruction surgery.

Two-thirds of patients who returned to their preinjury sport indicated that their self-reported performance level was equivalent to that of before their knee injury. While previous work has similarly shown that patients are satisfied in their ability to perform well in their sport after returning from ACL reconstruction surgery,2 there are no other data with which to directly compare this finding, as measures of performance have not previously been reported for similar young cohorts.

When investigating return to sport, it is important to consider the entire return to sport experience, which is inclusive of sport performance. This was highlighted in a recent consensus statement on return to sport where a distinction was made between returning to sport but not performing at a desired level and returning and performing at or above the preinjury level, as part of a return-to-sport continuum.1 Indeed, it should not just be the goal to return the young athlete to the field/court alone; consideration should also be given to the athletes perceived or documented ability, and it is hoped that future studies will collect similar data for comparison.

A high proportion (66%) of the young patient cohort were still participating in their preinjury sport at a mean 5 years after surgery. Perhaps this is not surprising since the average age of the patient group at follow-up was relatively young at 22 years. This is consistent with the findings of Morgan et al,10 who also reported that 66% of their younger patient cohort were participating in strenuous or very strenuous sports at 15 years postsurgery. While not statistically significant, patients who rated their ability to perform as similar to before injury were more likely to still be playing their preinjury sport. This may be relevant when considering why some patients continue to participate while others do not. However, the most common reason cited for ceasing participation in the preinjury sport was work or study commitments. Overall the patient group reported good knee function (with high SANE scores), which further suggests that non–knee-related factors play a role in the decision of whether to continue sport participation after ACL surgery.

The most common reason cited by the group of patients who never returned to their preinjury sport was fear of reinjury. This is consistent with previous work that has shown fear of reinjury to be associated with reduced rates of return to sport. Cumulatively, these data highlight the importance of psychological recovery in addition to physical recovery in athletes who wish to return to sport after ACL reconstruction.7,8,15

The sport participation profile of the cohort indicated that half of patients continued to play level I sports on a weekly basis. A potential limitation of this study is that the survey did not distinguish between the frequency of game and practice participation during the week, but this level of sports—regardless of setting—does nonetheless put the knee at most risk for further ACL injury. Recent cohort studies show rates for second ACL injury (graft rupture and contralateral ACL injury) to be as high as 25% to 35% in younger patients, and it has been speculated that 1 factor that may be contributing to these high rates is continued exposure from playing high-risk sports.10,12–14,16 The current data support this suggestion. Morgan et al10 found that young patients who returned to strenuous sports had a 2-fold increased risk for sustaining a contralateral ACL injury. Similarly, Kamath et al6 found that 94% of their young patient group who sustained their first ACL injury before entering college returned to high-level sport, but 37% sustained a further ACL injury. This leads to a conflicting situation in that it is important for young patients to return to sport for physical, social, and emotional development, but the risk of sustaining a further injury also needs to be minimized. The fact that a large portion of younger patients continue to play in level I sports that pose a risk for further ACL injury should be a consideration when planning and making return-to-sport decisions, although there is no current consensus on what return-to-sport criteria should be used to “clear” a younger patient to return to sport. However, recent studies suggest that patients who wait more than 9 months after surgery to return are less likely to have a subsequent injury.5

To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively report a range of return-to-sport outcomes in a younger ACL-reconstructed group. Although we were able to identify a large cohort of young patients, not all patients completed the study. A further limitation is that the study design was cross-sectional, and further work should be conducted to get a better understanding of the time to return to various sport activities as well as the timing of when patients choose to change activity.

This study also does not include the return-to-sport experience for the growing number of young athletes who sustain multiple ACL injuries, which will be a focus of future work. In this initial report, we decided to focus on a cohort of patients who had only 1 ACL injury to keep the cohort relatively homogenous and get a better understanding of non–knee-related factors that might influence continued participation in sport. These data are therefore generalizable to the 70% of younger patients who did not sustain a further ACL injury.

Conclusion

This study showed a 76% return-to-sport rate for younger ACL-reconstructed patients who have not had further ACL injury. The current data further highlighted that work/study commitments represent the primary reason that these young athletes discontinue their preinjury sport. A large proportion of young patients do, however, continue to play level I sports that involve jumping and hard pivoting. This continued exposure to high-risk sports has implications for the high second injury rates currently being reported in young ACL-reconstructed patients.

Footnotes

The authors declared that they have no potential conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from La Trobe University.

References

- 1. Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders A, et al. 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:853–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fear of re-injury in people who have returned to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15:488–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physcial functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fabricant PD, Lakomkin N, Cruz AIJ, Spitzer E, Marx RG. ACL reconstruction in youth athletes results in an improved rate of return to athletic activity when compared with non-operative treatment: a systematic review of the literature. JISAKOS. 2016;1:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:804–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamath GV, Murphy T, Creighton RA, Viradia N, Taft TN, Spang JT. Anterior cruciate ligament injury, return to play, and reinjury in the elite collegiate athlete: analysis of an NCAA Division I cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1638–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kvist J, Ek A, Sporrstedt K, Good L. Fear of re-injury: a hindrance for returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Langford JL, Webster KE, Feller JA. A prospective longitudinal study to assess psychological changes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mascarenhas R, Tranovich MJ, Kropf EJ, Fu FH, Harner CD. Bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft versus hamstring autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the young athlete: a retrospective matched analysis with 2-10 year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:1520–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morgan MD, Salmon LJ, Waller A, Roe JP, Pinczewski LA. Fifteen-year survival of endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients aged 18 years and younger. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Noyes FR, Barber SD, Mooar LA. A rationale for assessing sports activity levels and limitations in knee disorders. Clin Orthop. 1989;246:238–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of contralateral and ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of second ACL injuries 2 years after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1567–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Webster KE, Feller JA. Exploring the high reinjury rate in younger patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2827–2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Webster KE, Feller JA, Lambros C. Development and preliminary validation of a scale to measure the psychological impact of returning to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Phys Ther Sport. 2008;9:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Webster KE, Feller JA, Leigh WB, Richmond AK. Younger patients are at increased risk for graft rupture and contralateral injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]