Abstract

The effect of clinically recovered AKI (r-AKI) on future pregnancy outcomes is unknown. We retrospectively studied all women who delivered infants between 1998 and 2007 at Massachusetts General Hospital to assess whether a previous episode of r-AKI associated with subsequent adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, including preeclampsia. AKI was defined as rise in serum creatinine concentration to 1.5-fold above baseline. We compared pregnancy outcomes in women with r-AKI without history of CKD (eGFR>90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 before conception; n=105) with outcomes in women without kidney disease (controls; n=24,640). The r-AKI and control groups had similar prepregnancy serum creatinine measurements (0.70±0.20 versus 0.69±0.10 mg/dl; P=0.36). However, women with r-AKI had increased rates of preeclampsia compared with controls (23% versus 4%; P<0.001). Infants of women with r-AKI were born earlier than infants of controls (37.6±3.6 versus 39.2±2.2 weeks; P<0.001), with increased rates of small for gestational age births (15% versus 8%; P=0.03). After multivariate adjustment, r-AKI associated with increased risk for preeclampsia (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 5.9; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 3.6 to 9.7) and adverse fetal outcomes (aOR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6 to 3.7). When women with r-AKI and controls were matched 1:2 by age, race, body mass index, diastolic BP, parity, and diabetes status, r-AKI remained associated with preeclampsia (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2.1 to 10.1) and adverse fetal outcomes (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.7). Thus, a past episode of AKI, despite return to normal renal function before pregnancy, associated with adverse outcomes in pregnancy.

Keywords: acute renal failure, pregnancy, preeclampsia, clinical epidemiology

AKI is a global health epidemic and associated with the future development of hypertension and CKD.1–4 Although AKI is most often studied in elderly and critically ill populations, it is also a frequent occurrence in hospitalized children and young adults and associated with increased risk of future morbidity.5,6

Although the risk of AKI on the development of future CKD and death is well established, the consequence of an episode of AKI on health outcomes relevant to younger populations, such as pregnancy, has not been addressed. Pregnancy in women with advanced preexisting kidney disease is considered high risk.7,8 Several recent studies have reported adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with earlier stages of CKD as well, including those with normal GFR (CKD stage 1).9,10 These findings argue that even subclinical degrees of renal dysfunction, despite otherwise normal GFR, are important for healthy pregnancies. It is not known if adverse pregnancy outcomes are a long-term consequence of recovered AKI (r-AKI). Furthermore, rates of preeclampsia vary greatly across the world, with higher rates reported in low-income countries.11,12 In low-income countries, rates of AKI are also higher among young women.13 It is possible that variation in rates of preeclampsia may follow differences in the incidence of AKI among young women.14

The primary objective of our study was to determine if a history of recovered AKI (i.e., no subsequent CKD) increases the risk of subsequent adverse pregnancy outcomes. We hypothesized that a previous episode of AKI would result in increased risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, despite clinical recovery of renal function before pregnancy.

Results

Participant Characteristics

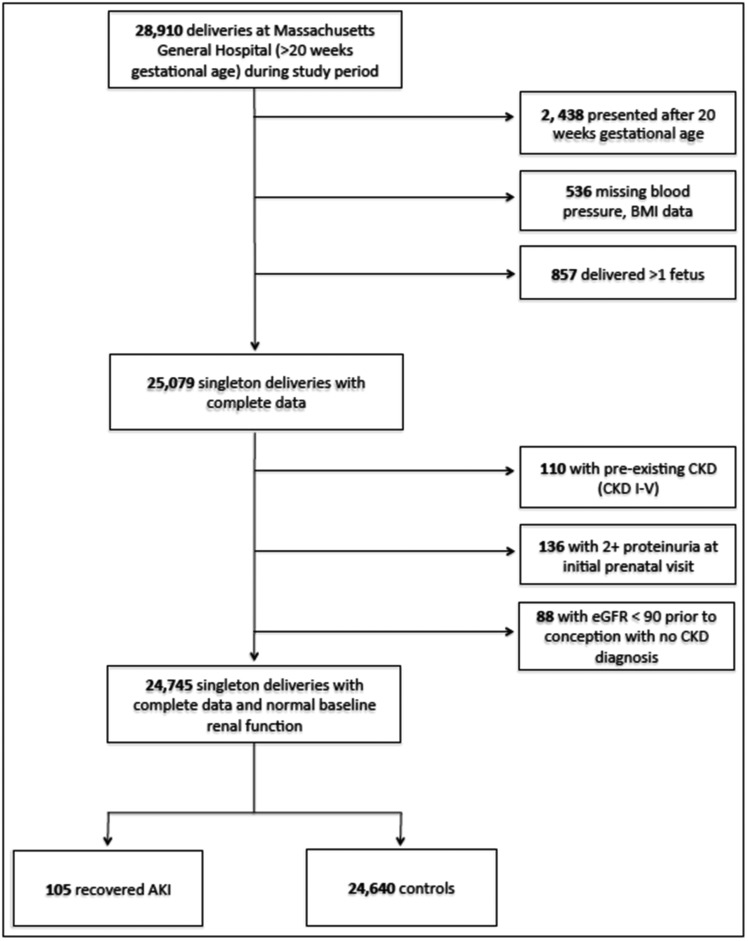

We performed a study of pregnancies in the Massachusetts General Hospital obstetric service birth database between September 1, 1998 and December 31, 2007. AKI was defined as a rise in serum creatinine concentration to 1.5-fold increase above baseline. Pregnancies in women with an episode of AKI with subsequent recovery of renal function (eGFR>90) before start of pregnancy (r-AKI; n=105) were compared with pregnancies in women without kidney disease (controls; n=24,640). Women with CKD were excluded (n=110) (Figure 1). At the first prenatal visit, women with r-AKI were of similar age, body mass index (BMI), parity, and gestational age at presentation compared with women without preexisting AKI (Table 1). The two groups were similar in marital status and education level; however, women in the control group were more likely to be of self–reported nonwhite race (34% versus 45%; P=0.04). The groups also had similar rates of preexisting hypertension and baseline systolic and diastolic BP recording at initial prenatal visit. More women in the r-AKI group had preexisting diabetes (12% versus 3%; P<0.001). Serum creatinine data during the 6 months before conception were available for 36% of the control cohort (n=8971). Preconception creatinine concentrations were similar between groups (0.70±0.20 versus 0.69±0.10 mg/dl; P=0.36). The baseline characteristics did not differ significantly in those controls with and without baseline creatinine measurements, with the exception of a modest different in education status (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion in study.

Table 1.

Main baseline clinical data in patients with r-AKI versus controls

| Characteristic | r-AKI (n=105) | Controls (n=24,640) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age at first prenatal visit, yr | 31.3±6.0 | 30.3±6.0 | 0.08 |

| Nonwhite race | 34 (36) | 45 (10,992) | 0.04 |

| Black | 6 (6) | 6 (1431) | |

| Hispanic | 18 (19) | 25 (6056) | |

| Asian | 2 (2) | 6 (1543) | |

| Other | 9 (9) | 8 (1962) | |

| Married | 68 (71) | 69 (16,980) | 0.75 |

| High school education | 68 (70) | 82 (17,738) | 0.24 |

| Initial prenatal visit characteristics | |||

| Gestational age at visit, wk | 12.7±5.4 | 12.7±5.8 | >0.90 |

| BMI at first prenatal visit, kg/m2 | 25.6±5.2 | 25.5±5.0 | 0.74 |

| Nulliparous | 46 (48) | 48 (11,743) | 0.67 |

| Preexisting hypertension | 3 (3) | 3 (590) | 0.96 |

| Preexisting diabetes | 12 (13) | 3 (731) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 112±14 | 111±11 | 0.32 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 70±10 | 68±9 | 0.13 |

| Preconception creatinine, mg/dl | 0.70±0.20 | 0.69±0.10 | 0.36 |

| Baseline urine dipstick proteinuria | |||

| Trace | 14 (15) | 19 (4728) | 0.22 |

| 1+ | 1 (1) | 2 (492) | 0.45 |

Data are presented as percentage (n) or mean±SD. Preconception creatinine (dated within 6 months of initial prenatal visit) was available in all patients with r-AKI and 8971 of controls.

Table 2 summarizes the etiologies of documented AKI episodes. A majority of patients suffered hemodynamic injury characterized primarily as acute tubular necrosis or prerenal azotemia (40%) or drug–induced renal injury (12%). AKI developed as a complication of a prior pregnancy in 12% of women in the cohort. This encompassed AKI from severe hyperemesis gravidarum, preeclampsia/hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, and obstetric hemorrhage. Postrenal etiologies accounted for 5% of AKI in the cohort. In 31% of patients who met criteria for r-AKI, an etiology could not be determined on the basis of review of the medical record; however, elevation of serum creatinine meeting the criteria for AKI was documented.

Table 2.

Etiology, severity, and stage of AKI in the cohort

| AKI characteristics | % (n) |

|---|---|

| AKI etiology | |

| Acute tubular necrosis/prerenal | 40 (42) |

| Drug induced | 12 (13) |

| Pregnancy associated (prior pregnancy) | 12 (13) |

| Obstruction/mechanical | 5 (5) |

| Unknown | 31 (32) |

| AKI severitya | |

| Duration from AKI to pregnancy, mo | 52±38 |

| Peak serum creatinine, mg/dl | 2.0±0.6 |

| AKI stage | |

| 1: 1.5–1.9 times baseline | 13 (14) |

| 2: 2.0–2.9 times baseline | 64 (67) |

| 3: 3.0 or greater times baseline or initiation of RRT | 23 (24) |

| RRT | 1 (1) |

Data are presented as mean±SD or percentage (n) unless otherwise indicated.

Maternal and Fetal Outcomes

Maternal and fetal outcomes in women with and without r-AKI are shown in Table 3. Mean gestational ages at delivery in women with and without r-AKI were 37.6±3.6 and 39.2±2.2 weeks, respectively (P<0.001). Women with r-AKI were more likely to have preterm deliveries and deliveries by cesarean section compared with women without AKI (40% versus 27%; P=0.02). Women with r-AKI had increased risks of preeclampsia, preterm preeclampsia, and early preterm preeclampsia (23%, 10%, and 7% versus 4%, 1%, and 0.4%; P<0.001). After adjustment for maternal age, maternal BMI, race, parity, history of diabetes, and diastolic BP at first prenatal visit, r-AKI remained significantly associated with adverse maternal outcomes. r-AKI was associated with a fivefold increased odds of preeclampsia compared with that in women without AKI (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 5.9; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 3.6 to 9.7). This finding was also true for preterm and early preterm preeclampsia (adjusted OR, 6.3; 95% CI, 3.1 to 12.7 and adjusted OR, 10.0; 95% CI, 4.0 to 25.3, respectively).

Table 3.

Primary maternal-fetal outcomes in patients with r-AKI versus controls

| Outcomes | r-AKI (n=105) | Controls (n=24,640) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | |||||

| Gestation age at delivery, wk | 37.6±3.6 | 39.2±2.2 | n/a | n/a | <0.001 |

| Cesarean section | 40 (42) | 27 (6690) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.6) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.5) | 0.02 |

| Gestational hypertension | 27 (28) | 16 (4019) | 1.9 (1.2 to 2.9) | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.6) | 0.05 |

| Preeclampsia | 23 (24) | 4 (1097) | 6.4 (4.0 to 10.1) | 5.9 (3.6 to 9.7) | <0.001 |

| Preterm preeclampsia, wk | |||||

| <37 | 10 (11) | 1 (334) | 8.5 (4.5 to 16.1) | 6.3 (3.1 to 12.7) | <0.001 |

| <34 | 7 (7) | 0.4 (96) | 18.3 (8.3 to 40.3) | 10.0 (4.0 to 25.3) | <0.001 |

| Fetal | |||||

| Baby weight (live births), g | 3210±823 | 3376±570 | n/a | n/a | 0.05 |

| Perinatal death | 3 (3) | 0.8 (186) | 3.9 (1.2 to 12.3) | 3.2 (1.0 to 10.6) | 0.05 |

| Small for gestational age | 15 (15) | 8 (2054) | 1.9 (1.1 to 3.3) | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.7) | 0.01 |

| NICU admission | 26 (27) | 8 (2058) | 3.7 (2.4 to 5.9) | 3.0 (1.9 to 4.9) | <0.001 |

| Composite fetal outcome | 40 (41) | 19 (4771) | 2.7 (1.8 to 4.0) | 2.4 (1.6 to 3.7) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as percentage (n) or mean±SD. Composite fetal outcome includes preterm delivery <37 weeks, NICU admission, fetal or neonatal death, and/or small for gestational age. Outcomes are adjusted for age, race, BMI, diastolic BP at first prenatal visit, history of diabetes, and parity. P values reflect the adjusted analysis for dichotomous outcome variables, and t tests were used for continuous outcome variables. n/a, not applicable.

Mean neonatal weights at birth from women with and without r-AKI were 3210±823 and 3376±570 g, respectively (P=0.05). Women with r-AKI were more likely to have small for gestational age offspring (15% versus 8%; P=0.03) and neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU; 26% versus 8%; P<0.001) compared with women without AKI. Although there was low number of perinatal deaths in the cohort (n=189), there were significantly more deaths in the offspring of mothers with r-AKI (3.0% versus 0.8%; P=0.02). This association, however, became nonsignificant in the multivariate logistic regression (adjusted OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.0 to 10.6). In offspring of mothers with r-AKI, 40% developed the composite adverse fetal outcome (preterm delivery, NICU admission, small for gestational age, or perinatal death) versus 19% in those without AKI (P<0.001). r-AKI was associated with increased odds of small for gestational age offspring, NICU admission, and the composite fetal adverse outcome (adjusted OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.7; adjusted OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.9 to 4.9; and adjusted OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6 to 3.7, respectively). Even after preeclampsia in the incident pregnancy was included in the multivariate model for fetal outcomes, all fetal outcomes except perinatal death remained significantly associated with r-AKI.

Sensitivity Analyses

As an additional method to control for potential confounders of adverse pregnancy outcomes, we performed two sensitivity analyses: one restricting the analysis to women with a baseline serum creatinine and a matched analysis. Women from the initial control cohort who had a serum creatinine drawn within 6 months of conception (n=8971) were used as the control population. Women with r-AKI delivered at earlier gestational age (37.6±3.6 versus 39.2±2.1 weeks; P<0.001) with higher rates of preeclampsia (23% versus 4%; P<0.001) compared with women from the initial control cohort who had a serum creatinine drawn within 6 months of conception (Table 4). Similarly, infants of women with r-AKI were more likely to be small for gestational age (15% versus 9%; P=0.02) and admitted to the NICU (26% versus 8%; P<0.001). These results were similar to those found in the main analysis.

Table 4.

Maternal-fetal outcomes in patients with r-AKI versus controls with baseline creatinine available

| Outcomes | r-AKI (n=105) | Cr-Controls (n=8971) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | |||||

| Gestation age at delivery, wk | 37.6±3.6 | 39.2±2.1 | n/a | n/a | <0.001 |

| Cesarean section | 40 (42) | 27 (2423) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.7) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.5) | 0.01 |

| Gestational hypertension | 27 (28) | 16 (1493) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.9) | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.5) | 0.06 |

| Preeclampsia | 23 (24) | 4 (379) | 6.8 (4.2 to 10.8) | 6.5 (3.9 to 10.8) | <0.001 |

| Preterm preeclampsia, wk | |||||

| <37 | 10 (11) | 1 (106) | 9.9 (5.1 to 19.1) | 7.5 (3.6 to 15.6) | <0.001 |

| <34 | 7 (7) | 0.3 (31) | 29.8 (9.0 to 48.4) | 12.8 (4.6 to 35.2) | <0.001 |

| Fetal | |||||

| Perinatal death | 3 (3) | 0.8 (69) | 3.8 (1.2 to 12.4) | 3.3 (1.0 to 11.1) | 0.05 |

| Baby weight (live births), g | 3210±823 | 3379±570 | n/a | n/a | 0.05 |

| Small for gestational age | 15 (15) | 9 (776) | 1.9 (1.1 to 3.3) | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.6) | 0.02 |

| NICU admission | 26 (27) | 8 (740) | 3.9 (2.5 to 6.1) | 3.1 (1.9 to 5.1) | <0.001 |

| Composite fetal outcome | 40 (41) | 19 (1753) | 2.6 (1.8 to 4.0) | 2.5 (1.6 to 3.7) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as percentage (n) or mean±SD. Composite fetal outcome includes preterm delivery <37 weeks, NICU admission, fetal or neonatal death, and/or small for gestational age. Outcomes are adjusted for age, race, BMI, diastolic BP at first prenatal visit, history of diabetes, and parity. P values reflect the adjusted analysis for dichotomous outcome variables, and t tests were used for continuous outcome variables. Cr-Controls, controls with baseline creatinine available; n/a, not applicable.

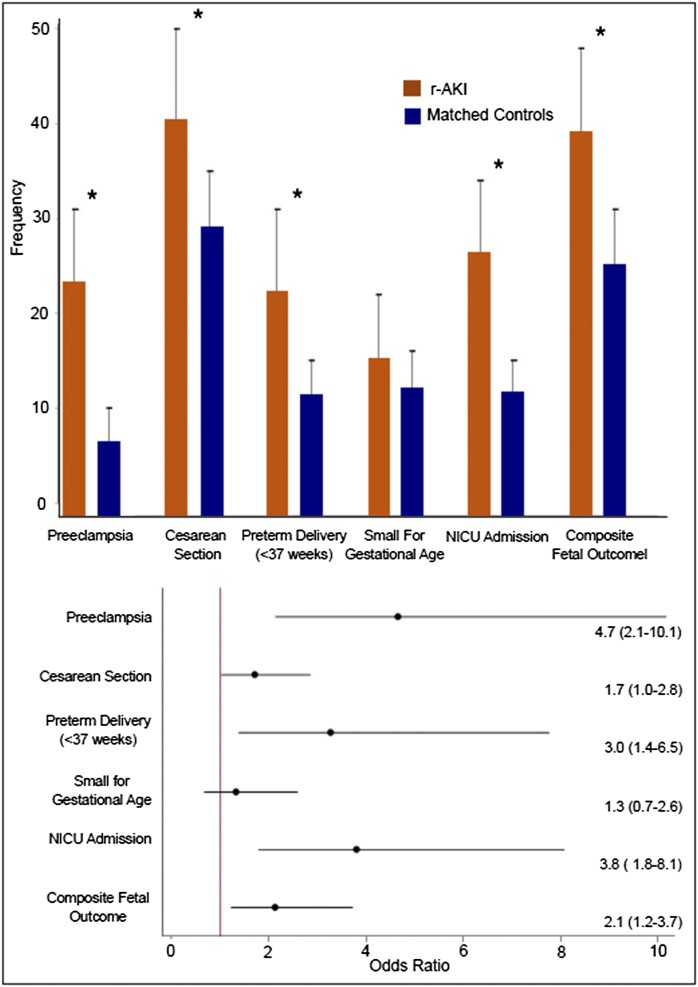

In the matched analysis, women with r-AKI were matched in a 1:2 fashion by age, race, BMI, parity, diabetes status, and diastolic BP in the first trimester to those without AKI. Maternal and fetal outcomes in women with and without r-AKI in the matched analysis are illustrated in Figure 2. Mean gestational ages at delivery in women with and without r-AKI were 37.6±3.6 and 39.0±2.4 weeks, respectively (P=0.001). Women with r-AKI were more likely to have preterm deliveries and delivery by cesarean section compared with matched controls (22% versus 11%; P<0.01 and 40% versus 29%; P=0.05, respectively). Women with r-AKI also had increased risk of preeclampsia (23% versus 7%; P<0.001; OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2.1 to 10.1). The results are similar to those in the unmatched analysis, with the exception of baby weight and small for gestational age offspring. Although women with r-AKI had smaller offspring (3210±823 versus 3300±646 g; P=0.34), the fetal birth weights and rates of small for gestational age offspring were not significantly different between the two groups. In a conditional logistic regression model, r-AKI remained significantly associated with preeclampsia, delivery by cesarean section, preterm delivery, NICU admission, and the composite fetal outcome (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Association of r-AKI with adverse maternal-fetal outcomes in a matched analysis. (Upper panel) Frequency (percentage) of adverse pregnancy outcomes between r-AKI and matched controls. Two controls were matched for each patient with r-AKI using age (±3 years), race, BMI (±2 points), parity, diabetes status, and diastolic BP in the first trimester (±3 mmHg). Error bars represent 95% CIs. *P value <0.05. (Lower panel) Association of adverse pregnancy outcomes with r-AKI from conditional logistic regression. Data are presented as ORs (95% CIs). Composite fetal outcome includes preterm delivery <37 weeks, NICU admission, fetal or neonatal death, and/or small for gestational age.

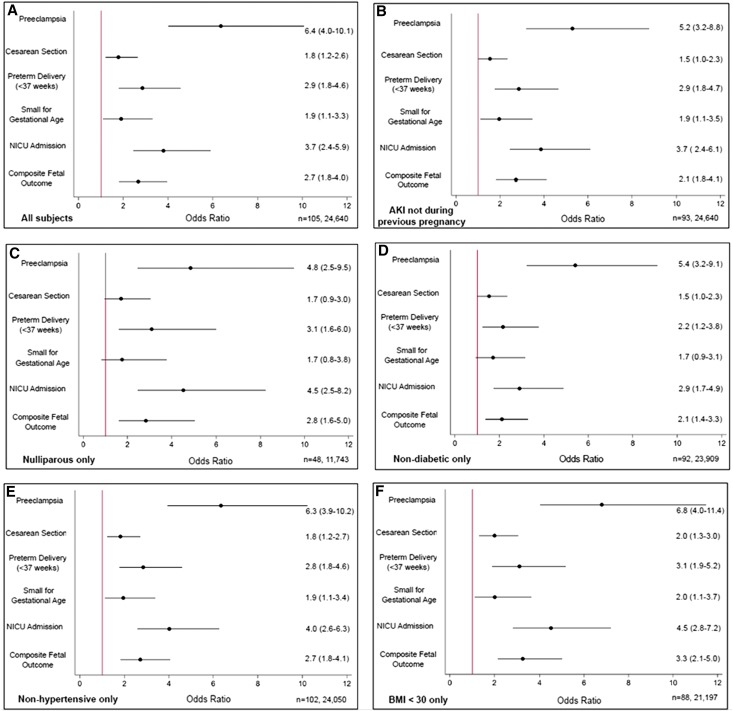

Subgroup Analyses

Because 12% of the episodes of AKI occurred during a prior pregnancy, we performed an analysis excluding these women and found a similar associated between r-AKI and risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Because we did not have information on preeclampsia during previous pregnancies for the entire cohort, we also performed an analysis in nulliparous women to exclude the possibility that adverse outcomes were related to prior preeclampsia and not prior AKI, and again, we found a similar association between r-AKI, preeclampsia, and adverse fetal outcomes. Additionally, we performed analyses excluding all women with diabetes, obesity, and hypertension. In all of these scenarios, a similar association between r-AKI and adverse pregnancy outcomes was observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis for main maternal-fetal outcomes in patients with r-AKI versus controls. Association of adverse pregnancy outcomes with r-AKI from logistic regression in various subpopulations. Data are presented as ORs (95% CIs). Composite fetal outcome includes preterm delivery <37 weeks, NICU admission, fetal or neonatal death, and/or small for gestational age. Reported n values are shown as n = r-AKI, controls.

Discussion

Our study shows that a previous episode of AKI, despite clinical recovery of renal function, is a risk factor for adverse maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnancy. r-AKI was associated with adverse outcomes independent of other significant comorbid conditions, including diabetes, chronic hypertension, and maternal obesity. This finding remained significant despite multiple methods to adjust for confounding, including a multivariate logistic regression, a matched analysis, and multiple subgroup analyses. Our findings raise the concern that, because these women have normal GFR estimates before conception, they may not be identified as high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Additionally, these results may help explain disparate rates of preeclampsia across the globe. Rates of preeclampsia differ by region, ranging from 1% to 15%.12 Similarly, the incidence of AKI differs across the world, and in low-income countries, young women represent a large proportion of patients with AKI.15 Given our findings, it is possible that the differing rates of preeclampsia may be linked to differing rates of AKI, even if AKI results in otherwise clinically documented recovery.

Normal pregnancy results in physiologic changes in the renal circulation critical to maternal and fetal health. In women with normal renal function, pregnancy is marked by in increased renal plasma flow. GFR increases throughout gestation.16 Given our understanding of the physiologic adaptation that affects the kidney during pregnancy, it is reasonable to question whether previous episodes of renal injury may result in adverse pregnancy outcomes. Poor pregnancy outcomes in women with advanced CKD have been reported for decades.17 It is intuitive that women with low GFR would do poorly in pregnancy. However, a recent study by Piccoli et al.9 found increased rates of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes even in women with early stages of CKD and normal GFR. Although this study did not specifically report rates of preeclampsia, the mothers with early-stage CKD had higher rates of preterm birth, and their offspring were more likely to be small for gestational age and admitted to the NICU, even when maternal GFR was normal before pregnancy. Of note, the gestational ages at delivery and small for gestational age estimates in our study are similar to the estimates from the work by Piccoli et al.9 in women with CKD stages 1 and 2. Preeclampsia is also reported to occur more frequently in pregnancy after nephrectomy for kidney donation.18 In contrast to women with r-AKI, however, kidney donors do not have an increased risk of preterm delivery or low birth weight, suggestive that placental function is less affected.

In light of pregnancy outcomes in kidney donors and women with preexisting CKD, our findings suggest that any previous renal damage, due to either acute or chronic injury, is associated with subsequent adverse pregnancy outcomes. The interaction between diseased kidneys and the fetoplacental unit during gestation remains unknown. Experimental studies in AKI have shown that aberrations in Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor signaling and endothelial injury are important in perpetuating renal damage that subsequently leads to CKD.19 Similarly, preeclampsia continues to be understood as a disorder of diseased endothelium and imbalance of pro- and antiangiogenic factors.20–22 Conditions with preexisting endothelial injury are associated with increased incidence of both AKI and preeclampsia. In our study, women with previous AKI had a higher rate of preeclampsia despite adjustment for preexisting diabetes and hypertension. Moreover, this result was evident after limiting the analysis to those with a first delivery and thus, no history of preeclampsia. Because our study shows only an association between AKI and future adverse pregnancy outcomes, there may also be an unknown confounder that predisposes women to both events. We, therefore, hypothesize that the underlying metabolic milieu (or other shared risk factors) of these women confers risk for both preeclampsia and AKI. Alternatively, subclinical vascular endothelial injury often associated with AKI may sensitize the vasculature to the toxic effects of circulating antiangiogenic factors that rise before term in all pregnancies. Experimental studies using animal models may shed further insights into the relationship between AKI and preeclampsia.

We noted that prior AKI was associated with an increased rate of cesarean delivery. This association was no longer significant when excluding pregnancies that resulted in preeclampsia, pregnancies that resulted in small for gestational age neonates, and pregnancies in women with preexisting hypertension and diabetes.

Our study has several limitations meriting discussion. We acknowledge that our definition of AKI is not the most current standard (a creatinine rise of 0.3 mg/dl over 48 hours) as defined in the 2012 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines.23 Because all of our data predate these revised guidelines, we found that providers in our medical system did not recognize 0.3 mg/dl as significant, and thus, follow-up testing was often absent. As a result, we may have missed patients with milder cases of AKI in the cohort. These women would have been included in our control arm; however, if they would have been included in the case arm, our point estimates may have been attenuated. Nevertheless, our analyses including only those women with available serum creatinine values within 6 months of start of pregnancy yielded point estimates similar to our overall analyses. Additionally, we used a definition of preeclampsia that differed from the definition set by the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy.24 The definition of preeclampsia varies by country.25,26 We chose a conservative definition of preeclampsia that was not subject to bias of diagnostic coding by providers or laboratory testing by providers. Our definition was more specific and likely underestimates the incidence of preeclampsia reported. Additionally, we also assessed hard outcomes, such as fetal weight, which is a surrogate of placental dysfunction. Another limitation is our use of dipstick proteinuria and not spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratios. Quantitative assessments of proteinuria were unavailable in a majority of women in the cohort. Although the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy continues to include dipstick urine protein in their definition of preeclampsia, we acknowledge superior diagnostic accuracy of quantitative methods of proteinuria detection.

In conclusion, our data show that a previous episode of AKI is a significant and independent risk factor for preeclampsia and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. This represents a newly defined group of high-risk women, especially in parts of the world where AKI in young women is more common. It would be interesting to address if AKI severity is associated with future preeclampsia risk in future studies. There was a small number of events in each AKI stage, and we did not have the power to address this relationship in our study. Although the overall frequency of AKI in our population was low, the consequences were significant to both mothers and their offspring. Health care providers should consider our findings when counseling women with previous AKI about the risk of adverse outcomes in pregnancy. More research is needed to address the clinical implications of previous episodes of AKI on pregnancy outcomes and identify strategies to modify future risk in these women. Additionally, our findings, taken in the context of CKD in the pregnancy literature, should prompt future research on the renal-placental-fetal axis.

Concise Methods

Subjects and Data Collection

The Massachusetts General Hospital obstetrics service provides both community care and high–risk obstetrics care for women from Boston and the surrounding New England area. We performed a cohort study of all pregnancies in the Massachusetts General Hospital obstetric service birth database between September 1, 1998 and December 31, 2007. Clinical information on all women who received prenatal care at Massachusetts General Hospital or one of its affiliated health care centers was reviewed in detail. This cohort encompasses a population of women from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. Clinical information, such as medical histories, prenatal BP measurements, and delivery information, was abstracted into the medical record prospectively and directly transferred into the study database.

For this study, we included all singleton pregnancies that lasted past 20-weeks gestation in women who received prenatal care during the study period. Both maternal and neonatal data were available, including flow charts with BP and urine analysis measurements. All women who were missing BP, urine dipstick, or weight (all part of standard care) at the first prenatal visit were excluded. Women who presented for initial prenatal care after 20-weeks gestation were also excluded (Figure 1). Detailed past medical information, including previous laboratory results, inpatient and outpatient medical documentation, and prior billing data, were obtained for the 10 years before pregnancy through the Partners Longitudinal Medical Record and the Partners Research Patient Data Registry.

Ascertainment of Exposures and Outcomes

We defined AKI on the basis of data obtained before pregnancy. Patients were identified using the KDIGO laboratory definition of AKI as “an increase in Serum Creatinine to 1.5 times baseline, which is known or presumed to have occurred within the prior 7 days.”23 Medical records for all women included in the cohort were reviewed in detail to document return to normal renal function (eGFR>90 ml/min by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation) before pregnancy.27 Women who presented with an elevated creatinine without a baseline but subsequently improved to an eGFR>90 ml/min before pregnancy were also included. Women who met criteria for AKI who were diagnosed with CKD, including (1) sustained eGFR <90 ml/min, (2) persistent proteinuria (2+ or greater proteinuria on dipstick or albumin-to-creatinine ratio >30 μg/mg), (3) identification of structural kidney lesions (e.g., autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease), or (4) chronic condition associated with kidney injury (e.g., lupus nephritis or ANCA vasculitis), were excluded. Etiology of AKI was determined through detailed chart review.

One hundred five women met the criteria for r-AKI. The first pregnancy after AKI was considered. The control population included 24,640 pregnancies in women without known preexisting kidney disease (both preexisting CKD and AKI with persistent low GFR). Women with 2+ dipstick proteinuria or greater at initial prenatal visit were excluded. Preconception creatinine reflects serum measurements documented at a maximum of 6 months before conception. To avoid measurement bias, we also included women with no history of AKI who lacked a serum creatinine measurement within 6 months of conception in the control group, because this represented a majority of the low-risk pregnancies in the cohort. A woman was considered to have preexisting hypertension if her BP before 20-weeks gestation was ≥ 140/90 mmHg or there was an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 9th Revision (ICD-9) code for hypertension before the start of pregnancy. A woman was considered to have preexisting diabetes based on the absence of a glucose loading test during pregnancy (glucose loading tests are contraindicated in women with preexisting diabetes) along with the presence of the ICD-9 code for diabetes before pregnancy. We reviewed 10% of the charts of women who met these criteria, and all met the definition of preexisting diabetes.

The diagnosis of preeclampsia was on the basis of BP and spot urine protein measurements made at prenatal visits. In women who were normotensive at their first prenatal visit (BP<140/90 mmHg) and lacked a diagnosis of chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension was defined as BP≥140/90 mmHg after 20-weeks gestation.24 In women who were hypertensive at their first prenatal visit (BP≥140/90 mmHg), gestational hypertension was defined by the presence of a rise in systolic BP >30 mmHg or a rise in diastolic BP >15 mmHg after 20-weeks gestation. Patients with preeclampsia were women with gestational hypertension and >2+ proteinuria after 20-weeks gestation or >1+ proteinuria after 20-weeks gestation with confirmation of the diagnosis in the electronic delivery record. Preterm preeclampsia and early preterm preeclampsia were defined as preeclampsia with delivery before 37- and 34-weeks gestation, respectively. We acknowledge that our definition of preeclampsia deviates from the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists definition.24 Because our data were collected before these revised guidelines, we felt that this represented a reproducible, specific definition of preeclampsia. Small for gestational age was defined as the 10th percentile for completed week of gestational age on the basis of national standards.28 Perinatal death was defined as infant death that occurred at <7 days of age or fetal death with a stated or presumed gestation of 20 weeks or more. The composite fetal outcome was defined by preterm delivery (<37 weeks), NICU admission, small for gestational age, or perinatal death.

We performed a matched sensitivity analysis. Using a pool of 24,640 women without preexisting kidney disease, we matched two controls without replacement for each woman with r-AKI using age (±3 years), race, BMI (±2 kg/m2), parity, history of diabetes, and diastolic BP in the first trimester (±3 mmHg).

Statistical Analyses

Characteristics of women with and without r-AKI were compared using paired t tests and Fisher exact tests as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were used to compare the odds of delivery by cesarean section, preeclampsia, premature delivery, small for gestational age, NICU admission, and perinatal death. Multivariate logistic regression models included variables associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal age, maternal BMI, maternal diastolic BP, maternal history of diabetes, race, and parity. In the matched analysis, conditional logistic regression was used as appropriate. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 14 (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.S.T. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Training grant T32 DK007540-30. C.E.P. was supported by the NIH Training grant T32 DK007028-41. R.T. was supported by NIH grant K24 DK094872-05.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2016070806/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Mehta RL, Cerdá J, Burdmann EA, Tonelli M, García-García G, Jha V, Susantitaphong P, Rocco M, Vanholder R, Sever MS, Cruz D, Jaber B, Lameire NH, Lombardi R, Lewington A, Feehally J, Finkelstein F, Levin N, Pannu N, Thomas B, Aronoff-Spencer E, Remuzzi G: International Society of Nephrology’s 0by25 initiative for acute kidney injury (zero preventable deaths by 2025): A human rights case for nephrology. Lancet 385: 2616–2643, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Shaw AD, Faselis C, Palant CE, Kimmel PL: Association between AKI and long-term renal and cardiovascular outcomes in United States veterans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 448–456, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu CY, Hsu RK, Yang J, Ordonez JD, Zheng S, Go AS: Elevated BP after AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 914–923, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald R, Quinn RR, Luo J, Li P, Scales DC, Mamdani MM, Ray JG; University of Toronto Acute Kidney Injury Research Group : Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA 302: 1179–1185, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mammen C, Al Abbas A, Skippen P, Nadel H, Levine D, Collet JP, Matsell DG: Long-term risk of CKD in children surviving episodes of acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: A prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 523–530, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGregor TL, Jones DP, Wang L, McGregor TL, Jones DP, Wang L, Danciu I, Bridges BC, Fleming GM, Shirey-Rice J, Chen L, Byrne DW, Van Driest SL: Acute kidney injury incidence in noncritically Ill hospitalized children, adolescents, and young adults: A retrospective observational study. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 384–390, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang JJ, Ma XX, Hao L, Liu LJ, Lv JC, Zhang H: A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes of pregnancy in CKD and CKD outcomes in pregnancy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1964–1978, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones DC, Hayslett JP: Outcome of pregnancy in women with moderate or severe renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 335: 226–232, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piccoli GB, Cabiddu G, Attini R, Vigotti FN, Maxia S, Lepori N, Tuveri M, Massidda M, Marchi C, Mura S, Coscia A, Biolcati M, Gaglioti P, Nichelatti M, Pibiri L, Chessa G, Pani A, Todros T: Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2011–2022, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccoli GB, Attini R, Vasario E, Conijn A, Biolcati M, D’Amico F, Consiglio V, Bontempo S, Todros T: Pregnancy and chronic kidney disease: A challenge in all CKD stages. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 844–855, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abalos E, Cuesta C, Carroli G, Qureshi Z, Widmer M, Vogel JP, Souza JP; WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health Research Network : Pre-eclampsia, eclampsia and adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes: A secondary analysis of the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG 121[Suppl 1]: 14–24, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abalos E, Cuesta C, Grosso AL, Chou D, Say L: Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 170: 1–7, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagasha P, Nakwagala F, Kwizera A, Ssekasanvu E, Kalyesubula R: Acute kidney injury among adult patients with sepsis in a low-income country: Clinical patterns and short-term outcomes. BMC Nephrol 16: 4, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li PK, Burdmann EA, Mehta RL; World Kidney Day Steering Committee 2013 : Acute kidney injury: Global health alert. Kidney Int 83: 372–376, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Cely CM, Colman R, Cruz DN, Edipidis K, Forni LG, Gomersall CD, Govil D, Honoré PM, Joannes-Boyau O, Joannidis M, Korhonen AM, Lavrentieva A, Mehta RL, Palevsky P, Roessler E, Ronco C, Uchino S, Vazquez JA, Vidal Andrade E, Webb S, Kellum JA: Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: The multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med 41: 1411–1423, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odutayo A, Hladunewich M: Obstetric nephrology: Renal hemodynamic and metabolic physiology in normal pregnancy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2073–2080, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz AI, Davison JM, Hayslett JP, Singson E, Lindheimer MD: Pregnancy in women with kidney disease. Kidney Int 18: 192–206, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg AX, Nevis IF, McArthur E, Sontrop JM, Koval JJ, Lam NN, Hildebrand AM, Reese PP, Storsley L, Gill JS, Segev DL, Habbous S, Bugeja A, Knoll GA, Dipchand C, Monroy-Cuadros M, Lentine KL; DONOR Network : Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia in living kidney donors. N Engl J Med 372: 124–133, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basile DP, Donohoe D, Roethe K, Osborn JL: Renal ischemic injury results in permanent damage to peritubular capillaries and influences long-term function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F887–F899, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA: Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 350: 672–683, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambers JC, Fusi L, Malik IS, Haskard DO, De Swiet M, Kooner JS: Association of maternal endothelial dysfunction with preeclampsia. JAMA 285: 1607–1612, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perni U, Sison C, Sharma V, Helseth G, Hawfield A, Suthanthiran M, August P: Angiogenic factors in superimposed preeclampsia: A longitudinal study of women with chronic hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension 59: 740–746, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 2[Suppl 1]: S1–S138, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy : Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 122: 1122–1131, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowe SA, Bowyer L, Lust K, McMahon LP, Morton M, North RA, Paech M, Said JM: SOMANZ guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 55: e1–e29, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redman CW: Hypertension in pregnancy: The NICE guidelines. Heart 97: 1967–1969, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW: A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr 3: 6, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.