Abstract

Patients enrolled in the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Cohort Study who exhibited overt proteinuria have been reported to show high nonalbumin proteinuria (NAP), which is characteristic of a tubulopathy. To determine whether African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension nephropathy (AASK-N) is a tubulopathy, we obtained urine samples of 37 patients with AASK-N, with 24-hour protein-to-creatinine ratios (milligrams per milligram) ranging from 0.2 to 1.0, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases repository and tested for seven markers of tubular proteinuria. By protocol, each sample had been collected in acetic acid (0.5%; mean final concentration). Compared with samples from patients with lupus nephritis or healthy black controls, AASK-N samples had lower amounts of six markers. Four markers (albumin, β-2-microglobulin, cystatin C, and osteopontin) were undetectable in most AASK-N samples. Examination by SDS-PAGE followed by protein staining revealed protein profiles indicative of severe protein degradation in 34 of 37 AASK-N urine samples. Treatment of lupus nephritis urine samples with 0.5% acetic acid produced the same protein degradation profile as that of AASK-N urine. We conclude that the increased NAP in AASK-N is an artifact of acetic acid–mediated degradation of albumin. The AASK-N repository urine samples have been compromised by the acetic acid preservative.

Keywords: AASK (African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension), albuminuria, urine preservation

The pathogenesis of the kidney disease studied in the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) is unclear. The African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension nephropathy (AASK-N) is often referred to as “hypertensive nephrosclerosis” because of the belief that it is caused by hypertension.1 However, there are at least two lines of evidence that argue against this. First, BP control did not result in an improvement in the rate of GFR decline.1 Second, the majority of AASK-N renal biopsies showed pervasive global glomerulosclerosis, but the degree of global glomerulosclerosis was not significantly correlated with the degree of arteriolar sclerosis and arteriole sclerosis, which are the hallmarks of hypertension-induced kidney injury.2

The presence of global glomerulosclerosis suggests that AASK-N may represent a primary glomerulopathy. However, AASK-N progressed relentlessly at low levels of proteinuria (for example, at 24-hour urine protein levels of <300 mg).3 Chronic glomerulopathies show little or no progression at this level of proteinuria.4 Progression at low levels of proteinuria is characteristic of a tubulopathy.5,6 Interestingly, a study in an animal model showed that primary tubular injury could cause global glomerulosclerosis.7

To assess whether AASK-N behaves as a primary tubulopathy, we analyzed 24-hour urine samples from the AASK Cohort Study obtained from the urine biorepository at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). This analysis initially involved measuring a panel of markers of tubular protein in urine from 37 patients with AASK-N. These samples were collected at the last visit of the AASK Cohort Study period (usually at 60 months from the AASK Cohort Study entry). Total storage time at −80°C was about 10 years.

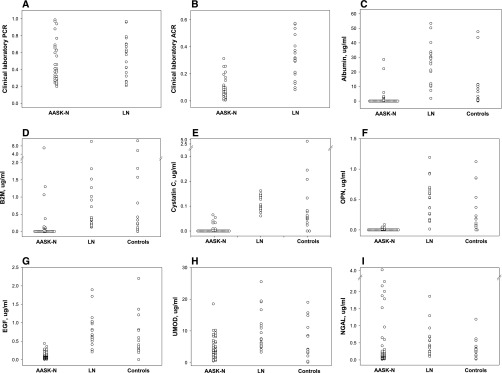

The urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (milligrams per milligram) measured in these AASK samples at the AASK central laboratory (The Cleveland Clinic) ranged from 0.20 to 0.99 (Figure 1A), and the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) ranged from 0.01 to 0.31 (Figure 1B). For comparison, 24-hour urines were analyzed from 20 patients with lupus nephritis (LN) and a similar protein-to-creatinine ratio range (0.21–0.97) (Figure 1A) but higher ACR range (0.08–0.57) (Figure 1B). Also analyzed were urine samples from 20 healthy black controls. The LN and control samples were from the Ohio SLE Study Cohort (OSS)8 and stored at −80°C for a period comparable with or longer than the AASK-N samples.

Figure 1.

Most urine analyte levels are low or undetectable in AASK-N patients compared with LN patients or healthy normal controls. Clinical laboratory measurements done on urine near the time of collection show (A) similar protein-to-creatinine ratio levels between patients with AASK-N and patients with LN but (B) lower ACR levels in patients with AASK-N compared with patients with LN. Measurements done on the same urines about 10 years later show undetectable levels in the majority of patients with AASK-N of (C) albumin, (D) β-2-microglobulin (B2M), (E) cystatin C, and (F) osteopontin (OPN); (G) lower levels of EGF compared with those in patients with LN and controls (P<0.001 for both); and (H) lower levels of uromodulin (UMOD) compared with those in patients with LN (P<0.01). (I) Urine levels of NGAL in the 10-year-old AASK-N urine were no different than those in patients with LN or control urines. PCR, protein-to-creatinine ratio.

The tubular proteinuria markers that were measured included albumin, β-2-microglobulin, cystatin C, osteopontin, EGF, uromodulin, and neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin (NGAL). Unexpectedly, albumin, β-2-microglobulin, cystatin C, and osteopontin (Figure 1, C–F) were undetectable in the majority of the AASK-N samples but detectable in nearly all of the LN urine samples and most of the control urine samples. Of the three markers that were measureable in the majority of the AASK-N samples, urine EGF levels were lower than the LN (P<0.001) or control (P<0.001) urine levels (Figure 1G), and urine uromodulin levels were lower than the LN urine levels (P<0.01) but not control urine levels (Figure 1H). AASK-N urine NGAL levels were comparable with LN or control NGAL levels (Figure 1I).

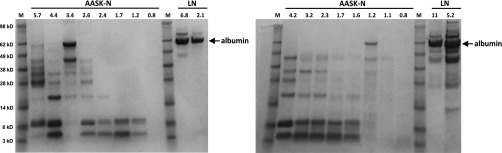

The difference between albuminuria levels measured in the AASK Cohort Study (Figure 1B) and those measured in this study (Figure 1C) and the fact that the AASK-N samples had low, often undetectable levels of tubular protein markers suggest that severe protein degradation had occurred in the AASK-N urine samples. To directly address this, the 37 AASK-N urine samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by protein staining of the gels; 34 of 37 samples showed substantial protein degradation, with almost complete loss of the albumin band and the appearance of two major bands below 10 kD. Urine from LN samples showed the predominant band as albumin, with no bands at or below 10 kD. Examples of this analysis are in Figure 2, which shows two SDS-PAGE gels, each containing eight AASK-N urine samples and two LN urine samples.

Figure 2.

Urine from AASK-N patients, but not from LN patients, shows extensive albumin degradation. Each lane contains 10 μl urine from patients with AASK-N (n=8 per gel) or patients with LN (n=2 per gel). The numbers above each lane refer to the microgram amount of protein in each 10-μl sample. Molecular mass markers are shown in lanes designated as M, and the corresponding relative molecular masses are shown on the far left in kilodaltons. The albumin bands are noted by the arrows. As shown, extensive albumin degradation is apparent in 14 of 16 AASK-N urine samples, with the majority of protein staining in these samples occurring in two bands at or below 10 kD. By comparison, the LN urine samples show intact albumin bands and no small molecular mass protein bands.

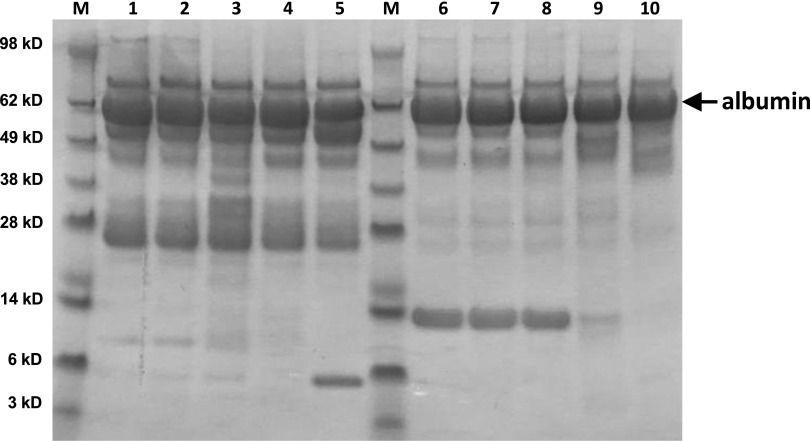

To test whether the degradation was limited to the samples that we received initially, a duplicate set of urine samples (different aliquots and no additional thaws) was obtained from the NIDDK as well as samples from the same patients but from 1 year earlier. In both sets of samples, the same degree of albumin degradation was observed by SDS-PAGE. To assess thawing effects, urine samples from five black patients with LN and overt proteinuria were analyzed by SDS-PAGE after eight freeze-thaw cycles. This showed little albumin degradation (data not shown). Finally, to assess the effects of temperature storage conditions, aliquots of the same five LN urine samples were stored at room temperature or 37°C for up to 5 days and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As can be seen in Figure 3, storage up to 5 days at 37°C resulted in little albumin degradation.

Figure 3.

Urine protein is stable at room temperature or 37°C for at least 5 days. Each lane contains 10 μl urine from two patients with LN (lanes 1–5 and lanes 6–10). Samples were analyzed fresh (lanes 1 and 6) or after storage at room temperature for 1 (lanes 2 and 7) or 5 days (lanes 3 and 8) or 37°C for 1 (lanes 4 and 9) or 5 days (lanes 5 and 10). Molecular mass markers are shown in lanes designated as M, and the corresponding relative molecular masses are shown on the far left in kilodaltons. The albumin bands are noted by the arrow. As shown, storage of urine at room temperature for as long as 5 days did not result in any visible albumin degradation. Similar results were seen for urines stored at 37°C, although one of two LN samples did show the appearance of one small band after 5 days at 37°C (lane 5).

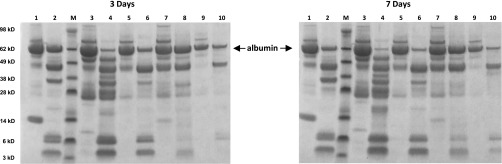

The AASK protocol for 24-hour urine collections required the addition of 250 ml 5% acetic acid as a preservative at the start of the urine collection. To test whether the presence of acetic acid was responsible for the albumin degradation in the AASK-N samples, acetic acid was added to urine samples from the five patients with LN at a final concentration of 0.5%, and the samples were incubated for various times at room temperature. This acetic acid concentration was comparable with the final concentration in the AASK-N samples on the basis of the average 24-hour urine volume of 37 patients with AASK-N (2100 ml). Figure 4 shows the effect of incubation at room temperature for 3 (Figure 4, left panel) and 7 days (Figure 4, right panel). The acetic acid–treated samples (even-numbered lanes in Figure 4) showed albumin degradation patterns similar to the AASK-N samples, although not as complete, with the 7-day incubated samples showing more degradation than the 3-day incubated samples. By comparison, the control samples (odd-numbered lanes in Figure 4) showed no degradation.

Figure 4.

Urine albumin is degraded by 0.5% acetic acid. Each lane contains 10 μl urine from five patients with LN (lanes 1 and 2; 3 and 4; 5 and 6; 7 and 8; and 9 and 10). Each urine sample was previously stored at room temperature for 3 or 7 days after the addition of 10% by volume water (controls; odd-numbered lanes) or 5% acetic acid (even-numbered lanes). Molecular mass markers are shown in lanes designated as M, and the corresponding relative molecular masses are shown on the far left in kilodaltons. The albumin bands are noted by the arrows. As shown, a final concentration of 0.5% acetic acid resulted in visible albumin degradation in a pattern similar to the AASK-N samples (Figure 2), and this pattern after 7 days storage was more pronounced than after 3 days of storage. By comparison, the controls showed no albumin degradation.

The degradation of albumin by acetic acid explains these finding of almost complete albumin degradation in the AASK-N urine samples and the low, often undetectable levels of the other tubular markers (Figure 1). The protocols for these measurements, nephelometry for albumin and dual antibodies for the tubular markers, require that the proteins have intact epitopes. Protein degradation by acetic acid disrupts these epitopes. These urine samples were collected directly into 250 ml 5% acetic acid and by protocol, could be kept refrigerated if delivered to the central laboratory within 7 days. Under these conditions, significant albumin degradation likely occurred by the time that the samples were tested at the AASK central laboratory. Interestingly, the colorimetric assay used for total proteinuria measurements in the AASK (pyrogallol red)9 does not detect urinary peptides well.10,11 This suggests that total proteinuria measurements reported in the patients in the AASK could also have been underestimated. However, the effect of acetic acid seems to be more pronounced on antibody-based measurements than on pyrogallol red–based measurements.10 Thus, the presence of acetic acid likely explains the low albuminuria levels (high nonalbumin proteinuria) reported in the AASK Cohort Study.9

The use of acetic acid as a preservative for 24-hour urine collection is not common but does appear in some standard protocols for a specific 24-hour urine test. For instance, the 24-hour urine collection protocol for the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology at Mayo Clinic lists preservative options for 64 different tests. Of those, acetic acid is listed as acceptable or preferable for 47 tests, with most involving measurements of salts or compounds by mass spectrometry. It is conceivable that, with so many tests considered compatible with acetic acid as a preservative, some 24-hour urine collection protocols might default to using acetic acid. This may be less of an issue for clinical testing that is done immediately after collection than for samples destined for biorepositories. Fortunately, the only other study with 24-hour urine samples that were collected in acetic acid and stored in the NIDDK biorepository seems to be the Modified Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study.

A recent analysis of urine biorepository samples collected from 12 different clinical studies reported that urine albumin levels are stable during long-term storage at −70°C.12 This report was on the basis of good concordance between ACR levels measured at the time of each study and ACR levels measured 10–20 years later. Interestingly, both the AASK and the MDRD Study urine samples were included in this study. It is unclear why these results seem to contradict our findings. However, the number of AASK (or MDRD) urine samples included in the total sample set was not specified, and their original albuminuria levels were also not specified. Many of the urine samples had ACRs<0.1 mg/mg, and direct testing for protein degradation was not reported.

In conclusion, this work shows that, if urine protein analyses are required, acetic acid should not be used as a preservative. Also, the previous report of high nonalbumin proteinuria in AASK-N is likely an artifact due to acetic acid–mediated albumin degradation, not evidence of a tubulopathy. Nevertheless, as discussed above, it remains plausible that AASK-N could be a primary tubulopathy.

Concise Methods

Urine Samples

Thirty-seven 24-hour urine samples were shipped from the NIDDK biorepository overnight on dry ice and immediately stored at −80°C. These samples were from the last visit of 37 participants in the AASK Cohort Study, all having protein-to-creatinine ratios ranging from 0.2 to 1.0. Urine samples from 20 patients with LN from the OSS with similar protein-to-creatinine ratio ranges and 20 healthy black controls were also included in this study. Before each testing, the urine samples were quickly thawed in a room temperature water bath and then, placed on ice until testing. Urine samples were then immediately refrozen at −80°C.

Kidney Injury Marker Panel Testing

A multiplex platform (Meso Scale Discovery [MSD], Rockville, MD) was used to test for seven different markers of kidney injury (MSD Kidney Injury Panel 5) according to MSD’s instructions. This platform is an immunoassay that uses a capture and detection antibody pair for each analyte. The assay was performed in The Ohio State University Clinical Research Center.

SDS-PAGE Analyses

Ten microliters each urine sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. The gels were 4%–15% gradient gels, and proteins were detected by Coomassie Dye R-250 staining (Imperial Protein Stain; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Prestained molecular masses (SeeBlue Plus2; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were included to estimate the relative size of the protein bands. Additional information is in Supplemental Material.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant X01DK105420 (to L.A.H.) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and by grant UL1TR001070 from the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2016080886/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wright JT Jr., Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Cheek D, Douglas-Baltimore JG, Gassman J, Glassock R, Hebert L, Jamerson K, Lewis J, Phillips RA, Toto RD, Middleton JP, Rostand SG; African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group : Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: Results from the AASK trial. JAMA 288: 2421–2431, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fogo A, Breyer JA, Smith MC, Cleveland WH, Agodoa L, Kirk KA, Glassock R: Accuracy of the diagnosis of hypertensive nephrosclerosis in African Americans: A report from the African American Study of Kidney Disease (AASK) trial. AASK Pilot Study Investigators. Kidney Int 51: 244–252, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appel LJ, Wright JT Jr., Greene T, Agodoa LY, Astor BC, Bakris GL, Cleveland WH, Charleston J, Contreras G, Faulkner ML, Gabbai FB, Gassman JJ, Hebert LA, Jamerson KA, Kopple JD, Kusek JW, Lash JP, Lea JP, Lewis JB, Lipkowitz MS, Massry SG, Miller ER, Norris K, Phillips RA, Pogue VA, Randall OS, Rostand SG, Smogorzewski MJ, Toto RD, Wang X; AASK Collaborative Research Group : Intensive blood-pressure control in hypertensive chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 363: 918–929, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, Landa M, Maschio G, de Jong PE, de Zeeuw D, Shahinfar S, Toto R, Levey AS; AIPRD Study Group : Progression of chronic kidney disease: The role of blood pressure control, proteinuria, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition: A patient-level meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 139: 244–252, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman AB, Johnson AM, Gabow PA, Schrier RW: Overt proteinuria and microalbuminuria in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1349–1354, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Methven S, MacGregor MS, Traynor JP, Hair M, O’Reilly DS, Deighan CJ: Comparison of urinary albumin and urinary total protein as predictors of patient outcomes in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 21–28, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grgic I, Campanholle G, Bijol V, Wang C, Sabbisetti VS, Ichimura T, Humphreys BD, Bonventre JV: Targeted proximal tubule injury triggers interstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 82: 172–183, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rovin BH, Song H, Birmingham DJ, Hebert LA, Yu CY, Nagaraja HN: Urine chemokines as biomarkers of human systemic lupus erythematosus activity. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 467–473, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toto RD, Greene T, Hebert LA, Hiremath L, Lea JP, Lewis JB, Pogue V, Sika M, Wang X; AASK Collaborative Research Group : Relationship between body mass index and proteinuria in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: Results from the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) cohort. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 896–906, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eppel GA, Nagy S, Jenkins MA, Tudball RN, Daskalakis M, Balazs ND, Comper WD: Variability of standard clinical protein assays in the analysis of a model urine solution of fragmented albumin. Clin Biochem 33: 487–494, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greive KA, Balazs ND, Comper WD: Protein fragments in urine have been considerably underestimated by various protein assays. Clin Chem 47: 1717–1719, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu CY, Ballard S, Batlle D, Bonventre JV, Böttinger EP, Feldman HI, Klein JB, Coresh J, Eckfeldt JH, Inker LA, Kimmel PL, Kusek JW, Liu KD, Mauer M, Mifflin TE, Molitch ME, Nelsestuen GL, Rebholz CM, Rovin BH, Sabbisetti VS, Van Eyk JE, Vasan RS, Waikar SS, Whitehead KM, Nelson RG; CKD Biomarkers Consortium : Cross-disciplinary biomarkers research: Lessons learned by the CKD biomarkers consortium. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 894–902, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.