The prevalence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) among patients on dialysis, specifically those with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), has increased dramatically over the past 15 years.1 Given that approximately 30% of hospitalizations and nearly 50% of deaths in patients on hemodialysis (HD) are attributable to cardiovascular causes, this trend is an increasingly important topic of discussion.1,2

In this issue of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Shroff et al. utilized hospital billing records from patients on HD in the United States.3 In brief, professional coding specialists determine the principal diagnosis as that condition, established after study, which resulted in the patient’s admission to the hospital. Secondary diagnoses include comorbidities, complications, and other diagnoses that are documented by the attending physician on the inpatient face sheet, discharge summary, history and physical, consultation reports, operative reports, and other ancillary reports. Age, sex, discharge destination, principal diagnosis, up to 24 secondary diagnoses, and up to 25 procedure codes are entered into a computerized algorithm to generate the Medicare diagnosis-related group that determines payment to the hospital.4 The authors demonstrated that although the overall AMI claims in patients on dialysis have increased, the proportion of those in the principal position decreased, whereas those in the secondary position increased.3 In particular, the overall and proportional increase of NSTEMI claims increased dramatically in both the principal and secondary coding positions. These data are consistent with the general population, where several studies have shown a sharp decline in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and a lesser decline or increase in NSTEMI.5,6 Interestingly, other data sources suggest that unstable angina is ever less frequent because more sensitive troponin assays clinch a diagnosis of NSTEMI over unstable angina in about 98% of cases.7 Thus, for coding as the principal diagnosis, the upward shift in NSTEMI is probably accounted for, in great part, by conversion from a prior unstable angina diagnosis to NSTEMI. Additionally, greater overall use of troponin in critically ill patients created detection bias over time, allowing greater numbers of NSTEMI to be detected. One recent study found that troponin testing is now done in 29% of all hospital admissions.8 STEMI coding as the principal diagnosis is also very interesting in that the changes described represent a decline in the natural occurrence of STEMI attenuated by a shift in coding patterns from STEMI in the secondary position to the principal diagnosis. The increasing importance and reliance of primary angioplasty and critical pathways for STEMI likely drove downcoding of STEMI listed secondarily from 30.7% of patients in 1993 to 6.4% in 2008. Thus, over time, when STEMI cases occurred, they were more likely to be coded as principal diagnoses in the later years.

What is the next wrinkle in decoding trends for hospital billing and the use of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision coding for AMI?9 Almost certainly the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2012 hospital penalties for 30-day readmission after AMI will play a role in how AMI is coded, particularly for a hospitalization within 30 days of a prior hospital stay.10 Because, as the authors point out, the diagnosis of AMI takes clinical judgment and calls for a characteristic rise and fall of troponin with supportive clinical evidence, there is ample opportunity in coding practice to adjudicate AMI and when these processes are applied, one would expect the principal diagnosis of AMI to become less frequent, particularly in hospitalizations within 30 days of an index AMI.11

It has been known for many years that patients on HD have higher baseline troponin concentrations and the introduction of high-sensitivity troponins has made this increasingly evident.12 When using troponin assays in 2001 with a healthy reference population to define an elevated troponin level, 30%–85% of asymptomatic patients on HD were reported to have elevated troponin.13 In 2015, using newer generation troponin T assays, 97% of patients on HD with a diagnosis other than AMI had a baseline troponin level above the 99th percentile.14 It is widely anticipated that ultra- or supersensitive troponin assays will become the standard worldwide.15 When this occurs, nearly every patient on HD will have a measurable “positive” troponin level above the 99th percentile for normal at all times. This will call for new approaches in using troponin in patients with CKD to discern between AMI and non-AMI.16 These advances in troponin assays will make it nearly impossible to use automated sources of data to ascertain the subtype of AMI as the authors list in Table 1.3 Far into the future we may be able to detect subtypes of AMI with machine learning to interpret serial electrocardiogram abnormalities, integration of catheterization lesion characteristics, and serial troponin values all in a database to be interrogated with longitudinal techniques. However, it is clear to the outcomes researcher today and from the paper by Shroff et al., we are far short of this vision.3

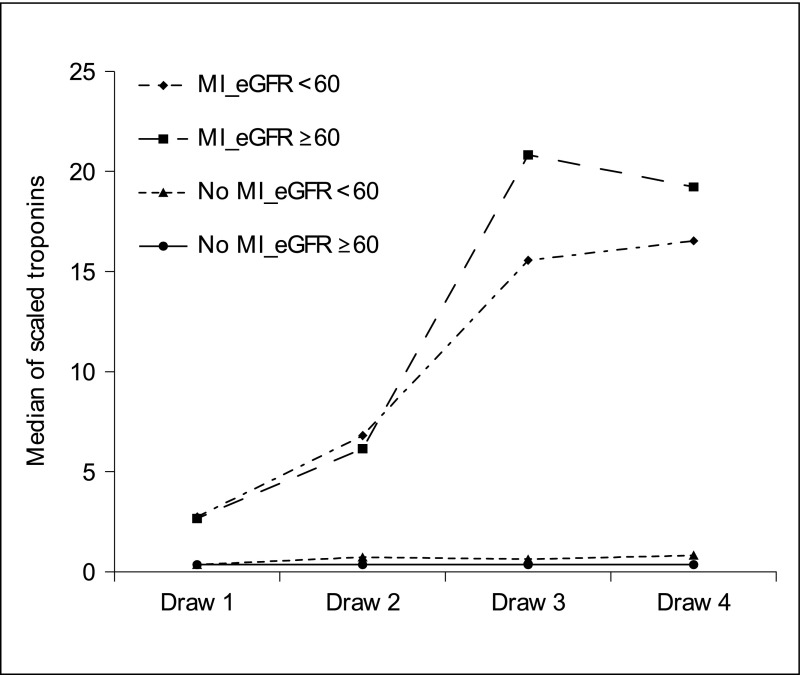

What is practical for today’s cardiorenal epidemiologist? Some have used a relative change in troponin levels of 20% to define and differentiate AMI in patients on HD instead of a single positive troponin.18 Recent studies by Tecson et al. and Vasudevan et al. showed the superiority of proportional rise of serial scaled troponin values compared with the 99th percentile cutoff troponin alone and note its ability to better distinguish patients with AMI from those without AMI, particularly in patients with CKD (Figure 1).11,16 Concordantly, Huang et al. evaluated the accuracy of troponin assays specifically for diagnosis of AMI in patients on HD and found that tracking the dynamic change in troponin levels in the short term significantly increased diagnostic accuracy in patients on HD.14 Lastly, for AMI coded in the secondary position, we can do much better if the principal diagnosis is also reported in the research manuscripts. Conditions associated with demand ischemia such as sepsis and hypotension make AMI more likely given the left ventricular hypertrophy and decreased capillary density known to exist in patients on HD, and thus, positive troponin/NSTEMI would be clinically concordant. In contrast, a case of volume overload due to dialysis noncompliance prompting admission, with no change in cardiac status, would make the diagnosis of positive troponin/NSTEMI call for more convincing clinical evidence. Thus the clinical context in which the troponin concentrations are being measured will become increasingly important.

Figure 1.

Serial measurements of scaled troponins by renal function and myocardial infarction (MI) status demonstrating that scaling allows easy visual distinction between myocardial infarction and nonmyocardial infarction patterns. Reprinted from reference 16, with permission.

In summary, we are living in a world of automated sources of data all around us. Our challenge is to harness this information and develop analytic strategies that help yield valuable inferences that inform the field as we move forward.

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Shroff GR, Li S, Herzog CA: Trends in mortality following acute myocardial infarction among dialysis patients in the United States over 15 years. J Am Heart Assoc 4: e002460, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herzog CA, Ma JZ, Collins AJ: Poor long-term survival after acute myocardial infarction among patients on long-term dialysis. N Engl J Med 339: 799–805, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shroff GR, Li S, Herzog CA: Trends in discharge claims for acute myocardial infarction among patients on dialysis [published online ahead of print February 20, 2017]. J Am Soc Nephrol doi:10.1681/ASN.2016050560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous: Available at: http://www.cengage.com/resource_uploads/downloads/1285867211_451554.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2017

- 5.Reynolds K, Go AS, Leong TK, Boudreau DM, Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Fortmann SP, Goldberg RJ, Gurwitz JH, Magid DJ, Margolis KL, McNeal CJ, Newton KM, Novotny R, Quesenberry CP Jr, Rosamond WD, Smith DH, VanWormer JJ, Vupputuri S, Waring SC, Williams MS, Sidney S: Trends in incidence of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction in the Cardiovascular Research Network (CVRN). Am J Med 130: 317–327, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS: Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 362: 2155–2165, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson SR, Sabatine MS, Braunwald E, Sloan S, Murphy SA, Morrow DA: Detection of myocardial injury in patients with unstable angina using a novel nanoparticle cardiac troponin I assay: Observations from the PROTECT-TIMI 30 Trial. Am Heart J 158: 386–391, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farber AJ, Suarez K, Slicker K, Patel CD, Pope B, Kowal R, Michel JB: Frequency of troponin testing in inpatient versus outpatient settings [published online ahead of print January 25, 2017]. Am J Cardiol doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, (ICD-10). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10.htm. Accessed March 4, 2017

- 10.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Readmissions Reduction Program, 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed March 4, 2017

- 11.Tecson KM, Arnold W, Barrett T, Birkhahn R, Daniels LB, DeFilippi C, Headden G, Peacock FW, Reed M, Singer AJ, Schussler JM, Smith S, Than MP, McCullough PA: Interpretation of positive troponin results among patients with and without myocardial infarction. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 30: 11–15, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ooi DS, House AA: Cardiac troponin T in hemodialyzed patients. Clin Chem 44: 1410–1416, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apple FS, Murakami MM, Pearce LA, Herzog CA: Predictive value of cardiac troponin I and T for subsequent death in end-stage renal disease. Circulation 106: 2941–2945, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang HL, Zhu S, Wang WQ, Nie X, Shi YY, He Y, Song HL, Miao Q, Fu P, Wang LL, Li GX: Diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in hemodialysis patients with high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Arch Pathol Lab Med 140: 75–80, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eggers KM, Venge P, Lindahl B: High-sensitive cardiac troponin T outperforms novel diagnostic biomarkers in patients with acute chest pain. Clin Chim Acta 413: 1135–1140, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasudevan A, Singer AJ, DeFilippi C, Headden G, Schussler JM, Daniels LB, Reed M, Than MP, Birkhahn R, Smith SW, Barrett TW, Arnold W, Peacock WF, McCullough PA: Renal function and scaled troponin in patients presenting to the emergency department with symptoms of myocardial infarction. Am J Nephrol 45: 304–309, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexandrescu R, Bottle A, Jarman B, Aylin P: Current ICD10 codes are insufficient to clearly distinguish acute myocardial infarction type: A descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res 13: 468, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang AY, Wai‐Kei Lam C: The diagnostic utility of cardiac biomarkers in dialysis patients. Semin Dial 25 388–396, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]