Abstract

Accurate treatment of solvent environment is critical for reliable simulations of protein conformational equilibria. Implicit treatment of solvation, such as using the generalized Born (GB) class of models arguably provides an optimal balance between computational efficiency and physical accuracy. Yet, GB models are frequently plagued by a tendency to generate overly compact structures. The physical origins of this drawback are relatively well understood, and the key to a balanced implicit solvent protein force field is careful optimization of physical parameters to achieve a sufficient level of cancellation of errors. The latter has been hampered by the difficulty of generating converged conformational ensembles of non-trivial model proteins using the popular replica exchange sampling technique. Here, we leverage improved sampling efficiency of a newly developed multi-scale enhanced sampling (MSES) technique to re-optimize the generalized-Born with molecular volume (GBMV2) implicit solvent model with the CHARMM36 protein force field. Recursive optimization of key GBMV2 parameters (such as input radii) and protein torsion profiles (via the CMAP torsion cross terms) has led to a more balanced GBMV2 protein force field that recapitulates the structures and stabilities of both helical and β-hairpin model peptides. Importantly, this force field appears to be free of the over-compaction bias, and can generate structural ensembles of several intrinsically disordered proteins of various lengths that seem highly consistent with available experimental data.

Summary

Effective simulation of protein conformational equilibria requires a balance between computational tractability and description of the essential physics. A newly developed multi-scale sampling method has been applied to re-optimize key physical parameters of the GBMV2 implicit solvent force field. The resulting force filed can successfully recapitulate key conformational properties of a set of helical and β-hairpin model peptides as well as intrinsically disordered proteins.

Introduction

Empirical force fields are essential for reliable molecular dynamics simulations. The state-of-the-art explicit solvent protein force fields have been steadily improved over the years1–4 and achieved remarkable successes in recent protein folding simulations 5–6. Yet, significant artifacts persist with these optimized explicit solvent force fields, especially when they are applied to describe the unstable states of proteins7–8. It has been shown that there is a strong tendency for virtually all widely used protein force fields to generate overly compact unfolded protein ensembles.3 This artifact is particularly evident in recent atomistic simulations of so-called intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs).9–13 There is a clear need to further balance the protein-protein, protein-water and water-water interactions, even though it remains debatable which component is the most problematic or what is the best approach towards rebalancing explicit solvent force fields.

Implicit solvent models have proven to be a viable alternative to explicit solvent that can dramatically extend the simulation timescale by eliminating the explicit representation of water.14–15 The basic concept of implicit solvent is to capture the mean influence of water molecules on the solute by direct estimation of the solvation free energy. This needs be achieved with sufficient computational efficiency and often involves continuum descriptions of water. Implicit solvent has enjoyed considerable success in biomolecular simulations in recent years, largely thanks to advances in Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) solvers and particularly the generalized Born (GB) approximations.16–21 The total solvation free energy in the GB-class of implicit solvent models is generally decomposed into electrostatic and nonpolar contributions,15

| (1) |

The nonpolar component, ΔGnp, corresponds to the free energy cost of solvating the uncharged solute, whereas the electrostatic component, ΔGelec, corresponds to the free energy cost of turning on the solute partial charges in water. Given the continuum electrostatics description of water, where the solute is represented as a low dielectric cavity embedded in a high dielectric solvent medium, the electrostatic solvation free energy can be efficiently calculated using the GB pairwise approximation,22

| (2) |

where rij is the distance between atoms i and j, qi and qj are the atomic charges for atoms i and j, RiGB and RjGB are the effective Born radii of atoms i and j, εs is the (high) dielectric constant of the solvent, and F is an empirical factor whose value may range from 2 to 10, with 4 being the most common one. The effective Born radius corresponds to the distance between a particular atom and its hypothetical spherical dielectric boundary that would yield the same atomic self electrostatic solvation free energy. Importantly, it has been demonstrated that the pair-wise GB approximation closely reproduces the “exact” ΔGelec derived from solving the PB equation as long as the effective Born radii are accurate.23–24 Another important advantage is that Eq. 2 allows analytical calculation of atomic forces and is thus particularly suitable for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. ΔGnp has been most commonly estimated directly based on solvent-accessible surface area (SA) using a phenomenological surface tension coefficient, γ, even though it has been recognized that ΔGnp actually needs to be further decomposed into a cavitation term and a solute-solvent dispersion interaction term.25–26

At present, the GB methodology is relatively mature, and many GB models can achieve high numerical accuracy through optimization of related numerical parameters to maximally reproduce the exact Born radii and/or solvation free energies derived from equivalent high-resolution PB calculations.18, 24 Such numerical accuracy is necessary but not sufficient for a GB (or PB) model to achieve high accuracy in reproducing experimental physical properties such as small molecule solvation free energies and protein conformational equilibria.20 The latter requires further parameterization of physical parameters, such as input atomic radii (for defining the location of the solute-solvent boundary) as well as key parameters of the underlying protein force field. How the solute–solvent boundary itself is defined in a given GB (or PB) model is also a key property that affects both nonpolar and electrostatic solvation free energies. Variational methods have been described to locate the boundary self-consistently for a given implicit solvent model.27–28 However, efficient empirical boundary definitions are used exclusively in models designed for biomolecular MD simulations. Smooth van der Waals (vdW)-like surfaces are simple to compute and numerically stable, but they lead to small high dielectric pockets in the protein interior.29–30 These interstitial voids may be transiently accessible to the solvent on the ensemble level and this justifies the use of vdW-like surfaces in PB calculations that are based on a single (averaged) structure.31 For a snapshot sampled during MD simulations, small interior high dielectric pockets are water inaccessible and unphysical. They lead to over-estimation of solvation for nonspecific collapsed structures with less ideal packing. Instead, the Lee-Richards molecular surface (MS),32 defined by rolling a (solvent) probe sphere over the solute molecule, arguably provides the most appropriate dielectric boundary. Inclusion of the reentrance surface in MS effectively eliminates small high dielectric pockets.

Among various analytical approximations, the GB using molecular volume (GBMV2) model has been one of the most successful models that can closely reproduce the original Lee-Richard MS.33 GBMV2 can nicely recapitulate both the locations and heights of the first desolvation peaks in potentials of mean force (PMFs) of pair-wise interactions calculated in TIP3P explicit solvent.34 A recent comparison of several implicit solvent models has found that GBMV2 provides the best agreement with experimental hydration free energies of a large set of small molecules.35 Trade-offs of using the sharp MS-like surfaces include increase in computational cost and potentially unstable atomic forces. The latter often requires smaller MD time steps of 1 to 1.5 fs.36 Furthermore, the presence of desolvation peaks, although realistic, slows down the kinetics of conformational transitions. Together, these limitations have contributed to significant challenges in deriving a sufficiently optimized GBMV force field that can provide an accurate description of protein conformational equilibria.34 Such optimization efforts typically require the calculation of well-converged conformational ensembles of a set of helical and β-hairpin model peptides,37 which has proven to be very challenging for MS-based GB models. For example, satisfactory convergence could not be achieved in GBMV2 or a related GBSW/MS2 implicit solvent model for a set of GB1p-derived β-hairpins with multiple temperature replica exchange (T-RE)38 MD simulations of up to 150 ns per replica in length.34

Recently, we developed a multi-scale enhanced sampling (MSES) method that could greatly accelerate the sampling of large-scale conformational transitions of proteins.39–40 Efficient coarse-grained models are coupled with all-atom force fields to enhance the sampling of atomistic protein energy landscape. The bias from the multi-scale coupling is removed by Hamiltonian replica exchange41, allowing one to benefit simultaneously from faster transitions of coarse-grained modeling and accuracy of atomistic force fields. It has been shown that MSES is highly effective in driving reversible folding transitions, up to ~100-fold for small β-hairpin in implicit solvent.40 In this work, we exploit enhanced sampling efficiency of MSES to revisit the optimization of the GBMV2/SA implicit solvent together with the underlying CHARMM36 protein force field.1, 42 The overall optimization strategy is similar to what was successfully utilized for optimizing the GB with a smooth switching (GBSW) protein force field.37 It involves recursive optimization of key physical parameters of the GBMV2 protein force field based on solvation free energies of peptide backbone and side chain analogs, PMFs of their pair-wise interactions, and importantly, conformational equilibria of carefully selected model peptides. The optimized GBMV2 force field will also be evaluated for atomistic simulation of three IDPs of various length and complexity that have been characterized experimentally. We note that Simmerling and coworkers have recently developed and optimized a GB-neck2 model that is highly successfully in folding of proteins with diverse topologies.43–44 This model includes a simple but efficient “neck” correction to mimic MS-like solute-solvent boundary. Its optimization was also enabled by important advances in sampling capability, more specifically, the development of GPU-based MD codes that are up to 700-fold faster than conventional CPU-based ones.45

Method

Optimization of atomic input radii

We mainly focused on a set of physical parameters of the GBMV2 protein force field including atomic input radii, the surface tension coefficient (γ), and peptide backbone torsion energetics in this work. In principle, other parameters of the underlying CHARMM36 force field, e.g. Lennard-Jones parameters and atomic partial charges, need to be co-optimized together with the new solvation parameters to achieve full consistency and maximal transferability. However, an attempt to re-parameterize the underlying protein model is highly nontrivial. As a compromise, a reasonable approach is to focus on adjusting the input radii and backbone torsion energetics. The limitation of such optimization strategy is that one might incorrectly compensate for certain artifacts of the underlying protein model. The atomic input radii and γ are first systematically optimized to reproduce the experimental solvation free energies of amino acid side chain analogs46 and PMFs of their pair-wise interactions previously calculated in TIP3P explicit solvent37 (also see Fig. S1). We note that the key to accurately describe peptide conformational equilibria relies on the delicate balance between sets of competing interactions, e.g. the solvation preference of side chains and backbones against the solvent-mediated interactions between these moieties in a complex protein environment. These two competing interactions are often opposing and mostly cancel out, and small relative errors in either term might accumulate and lead to a substantial shift in the balance.

Model peptides

After initial optimization of input radii based on PMFs, conformational equilibria of a set of helical and β-hairpins peptides were used to guide the iterative refinement of the implicit solvent parameters together with the peptide backbone torsion energetics. This is critical to achieve a sufficient level of cancellation of errors at the peptide and protein level after initial parameterization based on small model compounds. The key objective is to balance the solvation term with the underlying CHARMM36 protein force field, such that both the experimental structures and stabilities of these model peptides can be sufficiently recapitulated. The model peptides include Ala5, (AAQAA)3 and a series of β-hairpins derived from the protein G B1 domain, which are frequently used in protein force field optimizations.47–48 (AAQAA)3 is a weakly structured helical peptide that has been characterized in detail by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). 49 The series of β-hairpins includes GB1p (GEWTYD DATK TFTVTE), GB1m1 (GEWTYD DATK TATVTE), and GB1m3 (KKWTYN PATG KFTVQE) (loop regions underlined). NMR chemical shift analysis have revealed that GB1p is ~42% folded at 278 K.50 The mutant GB1m1 reduces the hairpin stability to ~6% folded, and the mutant GB1m3 is ~86% folded because more rigid proline-containing loop increases the stability.50 Difference in the stabilities of these three homologous peptides offers a particularly useful control for the force field optimization. Ala5 peptide was also simulated to further examine the proper balance of various secondary structures in comparison to previous NMR and simulation studies.51–52 The termini of all model peptides are neutralized using amine (-NH2) and carboxyl group (-COOH).

Recursive optimization of protein backbone torsion potentials

A critical bottleneck to previous efforts of optimizing GB models with MS-like surfaces has been difficulty in calculating well-converged conformational equilibria of β-hairpins. For this, we mainly rely on MSES to accelerate the conformational sampling of model peptides.40 In MSES, the atomistic and coarse-grained resolutions were simulated simultaneously and coupled by a restraint potential. A single sequence-flavored Gō-like model53 was generated using with the Multiscale Modeling Tools for Structural Biology (MMTSB) Go-model builder,54 and used in simulations of all three GB1p β-hairpins. Each residue is represented by a single Cα-bead and specific native interactions are described by the Miyazawa-Jernigan (MJ) statistical potentials.55 Another sequence-flavored Gō-like model was generated for (AAQAA)3 using an ideal helix, and the strength of all native contacts was then uniformly scaled down from the original values to reflect the weak helicity of the peptide.39

All MSES simulations were performed in CHARMM56–57 with a slightly modified MMTSB toolset40. The parameters used in the MSES restraint potential were k = 1.0 kcal/mol/Å2, s = 1, ds = 2.0 Å, and fmax = 0.1 kcal/mol/Å.40 Langevin simulations were performed with a friction coefficient of 0.1 ps−1, and exchanges were attempted every 2 ps. SHAKE58 was used to constrain the lengths of all bonds involving hydrogen atoms and the dynamic time step was 2 fs. The recommended values were used for various numerical parameters of GBMV2 configuration, with the scaling factor of VSA function P3 = 0.65, exponent in exponential of Still equation P6 = 8, multiplicative factor of the αi (SLOPE = 0.9085), shifting factor of αi (SHIFT = −0.102) and smoothing factor for tailing off of volume (BETA = −12). We note that GBMV2 appear to be rather sensitive to these numerical parameters and that even small changes could lead to significantly differences in the calculated conformational ensembles. The number of replicas used in MSES simulations varied depending on the model peptides. For GB1p-series of β-hairpins, MSES simulations involved 8 replicas and distributed exponentially between 270 and 450 K. For (AAQAA)3, 16 replicas were distributed exponentially between 270 and 500 K. These conditions were assigned by having exponential distributions for both temperature and multi-scale coupling constant.40 Two independent simulations starting from the folded (control) and fully extended (folding) structures were always performed for each peptide for convergence diagnosis. In addition, an additional simulation of the GB1p peptide was performed with mixed folded and unfolded initial structures, randomly selected from the final snapshots of 100 ns control and folding MSES runs. For (Ala)5 simulation, only a single temperature replica exchange (T-RE) simulation was performed, with 8 replicas distributed exponentially between 300 and 450 K and initiated from a fully extend structure.

The iterative optimization relies on manual adjustment of the input radii of important backbone atoms (including amide nitrogen and carbonyl oxygen) and peptide backbone dihedral energetics. We focused on adjusting the CMAP term59–60 in the helical φ/ψ region and strength of backbone hydrogen-bonding interactions (via input radii of backbone atoms) to properly balance the secondary structure preference. The challenge is the expensive computational costs of re-calculating converged conformational equilibria of those model peptides. For this, Hamiltonian mapping61 was used to re-weight the whole conformational ensembles for efficient scanning of a large set of parameters of the backbone input radii and torsion energetics. The experimental secondary structure tendencies of model peptides were used to select the best parameters for new MSES simulations, allowing the final optimized parameters to be identified with minimal rounds of actual peptide simulations.

Benchmark simulations of disordered protein ensembles

The optimized GBMV2 force field has been further examined using three IDPs of various lengths including: KID,62 activator for thyroid hormone and retinoid receptors (ACTR),63 and the charge rich RS peptide.64–65 KID (residues 119–146: TD SQKRR EILSR RPSYR KILND LSSDA P) is one of the most studied IDPs.62, 66–67 It lacks stable tertiary structures in isolation but folds into two helixes on binding to the KIX domain of the CREB binding protein (CBP).62 NMR chemical shift analysis has revealed that helix αA (residues 120–129) is about 50–60% folded, while helix αB (residues 134–144) is only 10–15% folded.67 ACTR simulated here includes residues 1040–1086 (in human ACTR numbering) and the sequence is: E GQSDE RALLD QLHTL LSNTD ATGLE EIDRA LGIPE LVNQG QALEP K. Three helical segments can be identified in ACTR when bound to the NCBD domain of CBP,63 spanning residues 1044–1058, 1063–1071, and 1072–1080, respectively. The RS peptide (residues 1–24; GAMGP SYGRS RSRSR SRSRS RSRS) is a well-studied IDP with rich arginine and serine residues, and thought to modulate protein-RNA interactions.64 Its structural properties have been well-characterized by NMR64 and small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS).13 The termini of those model IDPs are neutralized using amine (-NH2) and carboxyl group (-COOH). The CG models generated were based on available structures of KID (PDB ID: 1KDX) and ACTR (PDB ID: 1KBH), and the strength of all native contacts was using the default values. For RS peptide, the ideal helix conformer is used to build the CG model, and the strength of all native contacts was then uniformly scaled down half of the original values. The MSES parameters are same as them used in the model peptides. For KID and ACTR, MSES simulations involved 16 replicas and distributed exponentially between 300 and 500 K. For RS peptide, 12 replicas were distributed exponentially between 298 and 450 K. Both control and folding simulations were included for convergence diagnosis.

Results and Discussion

Optimization of GBMV2 input radii

As noted above, the dielectric boundary is a key physical property that governs the solvation free energies. An early study has shown that using the default vdW radii in CHARMM22 (or similarly CHARMM36 in this work) is nearly optimal for GBMV2 in its ability to reproduce PMFs of pair-wise interactions calculated in TIP3P explicit solvent (also see Fig. S1, red traces).34 As such, CHARMM36 vdW radii are used as the default for atomic input radii of GBMV2. Nonetheless, numerical parameterization of the input radii of selected atom types could further improve the agreement with TIP3P results for both the solvation free energies and PMFs between polar and nonpolar amino acid side chains. During the Monte Carlo optimization, care was taken to avoid over-fitting of the input radii and only changes that lead significant improvement in agreement with TIP3P results were included. The final changes to the input radii are summarized in Table 1. Most changes from the default CHARMM vdW radii are small. The largest changes were made to the input radii of peptide backbone carbonyl oxygen (O) and amide nitrogen (N), which were further co-optimized with the peptide backbone torsion energetics based on model peptide simulations (see the next section). The original recommended value for the surface tension coefficient, γ = 0.005 kcal/ mol/Å2, was found to be indeed optimal and thus not changed. The PMF profiles of pair-wise interactions of polar and nonpolar amino acid sides are shown in Fig. S1 and S2. The solvation free energies of amino acid side chain analogues are shown in Fig. S3. We note that several polar and nonpolar pairs are particularly difficult for GBMV2 to reproduce the TIP3P results and persist to be problematic that don’t agree well with TIP3P results (Figs. S1 and S2). These problematic pairs were noted in previous optimization efforts as well.34 In addition, it should be noted that the standard SA model is likely inadequate for describing the protein conformational dependence of nonpolar solvation. Arguably, the nonpolar component needs to be further decomposed into a cavity hydration term and a solute-solvent dispersion interaction term.25 The solute-solvent dispersion attraction could be estimated using a continuum vdW solvent model.25 It is also critical to capture the length scale dependence of hydrophobic associations, such as using context dependent effective surface tension coefficient.68 It is likely that proper description of the length-scale dependence of hydrophobic solvation and the solute–solvent dispersion interactions can further improve the agreement with TIP3P results.26

Table 1.

Final atomic input radii for the optimized GBMV2 implicit solvent protein force field. The default CHARMM36 vdW radii are used for all atoms not shown.

| Group | Atom | vdW (Å) | GBMV2 (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | Varies | – | |

| Backbone | O | 1.70 | 1.65 |

| N | 1.85 | 1.77 | |

| C | 2.06 | 2.05 | |

| CA | 2.06 | – | |

| Sidechains | |||

| All | CB | 2.175 | – |

| CD, CG | 2.275 | – | |

| Lys | NZ | 1.85 | – |

| CE | 2.175 | 2.14 | |

| Arg | NH* | 1.85 | 1.88 |

| NE | 1.85 | 1.95 | |

| CZ | 2.00 | 2.06 | |

| Glu | OE* | 1.70 | 1.68 |

| CD | 2.00 | 2.10 | |

| Gln | NE2 | 1.85 | 1.91 |

| OE*, OD* | 1.70 | – | |

| Hsp | ND1, NE2 | 1.85 | 1.82 |

| His/Hsd | ND1 | 1.85 | 1.82 |

| NE2 | 1.85 | 1.80 | |

is a wildcard character.

denotes no change from the default CHARMM36 vdW radius.

Iterative tuning backbone torsion profiles based on peptide conformational equilibria

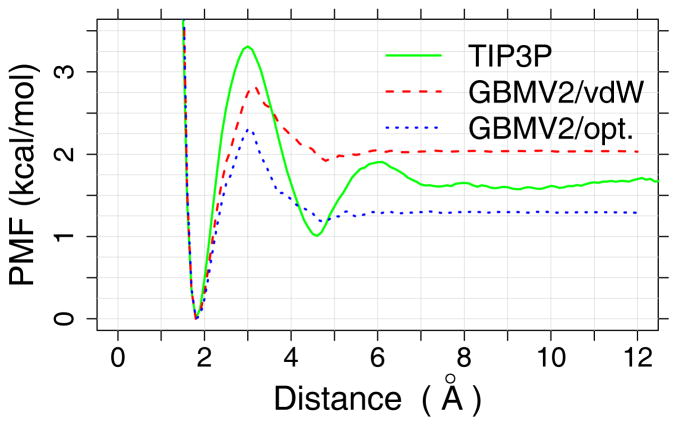

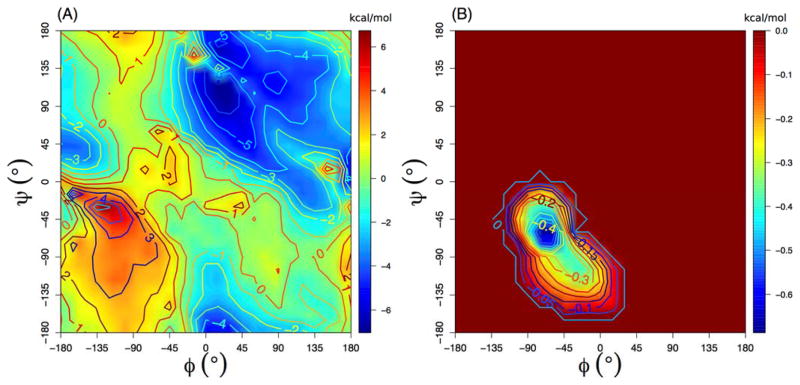

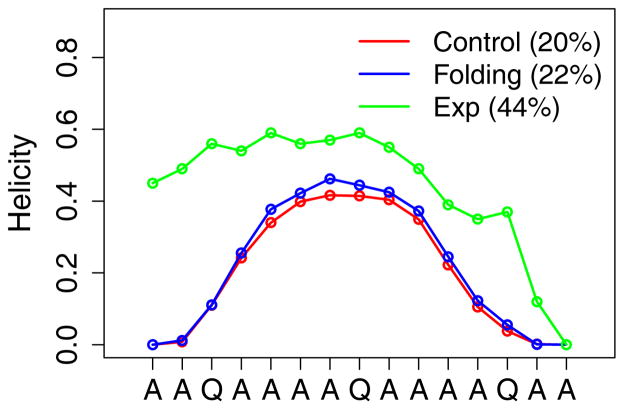

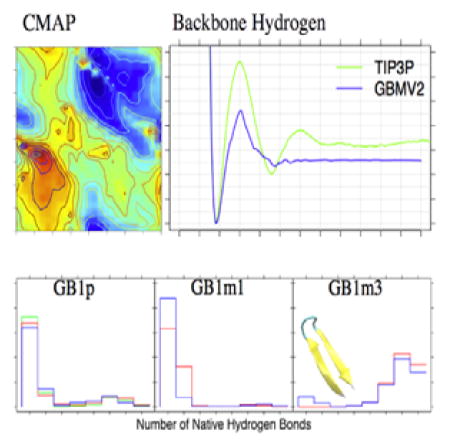

The CMAP terms in CHARMM36 has been extensively optimized to provide improved balance among various secondary structure in TIP3P water.1 Using CHARMM36 CMAP directly with GBMV2 together with the default vdW values for input radii only slightly over-estimates the residue helicity of (AAQAA)3 (Fig. S4A), but significantly over-stabilize both GB1p and GB1m1 β-hairpins (Fig. S4B). This can be likely attributed to over-stabilized backbone hydrogen-bonding interactions (Fig. 1, red trace), which needs to be further co-optimized with the peptide backbone torsion in order to properly balance the peptide secondary structure propensities (see Methods). The strength of backbone hydrogen-bonding interactions in GBMV2 is mainly modulated by the input radii of the peptide backbone, and particularly, those of C and O (see Table 1). The final backbone parameters derived from the iterative optimization are given in Table 1, and the final tuned CMAP for all non-Proline residues is shown in Fig. 2. These changes substantially reduce the strength of backbone hydrogen bonding, by ~1.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 1, blue trace), which is compensated by stabilization of the helical region in the ϕ/ψ space (Fig. 2). As the result, the optimized GBMV2 force field is able to reasonably recapitulate the residue helicity of (AAQAA)3 (see Fig. 3). We note that the simulated ensembles are very well converged, and the RMSD between residue helicity curves is only 0.022 between control and folding MSES runs. The simulated helical content is slightly weaker than the NMR results49, but this seems a necessary compromise to sufficiently balance both helical and β-strand propensities. We note that the optimized CHARMM36 explicit solvent protein force field also leads to a slightly under-estimated helicity for (AAQAA)3.48

Figure 1.

PMFs of the backbone hydrogen-bonding interaction between a modified alanine dipeptide dimer (see insert) in TIP3P water and GBMV2 implicit solvent with two different sets of atomic input radii (see Table 1). Details of the dimer and calculation of the TIP3P PMF were described previously.34, 37

Figure 2.

(A) Optimized CMAP for GBMV2 for all non-Proline residues, and (B) the change made to the original CHARMM36 CMAP.

Figure 3.

Average residue helicity of peptide (AAQAA)3 at 270 K derived from various segments of the control and folding simulations. The 80–140 ns fragments were used for data analyses. The average helicities were shown in parentheses. The experimental values were taken from Shalongo et al. 1994 (See Ref 49).

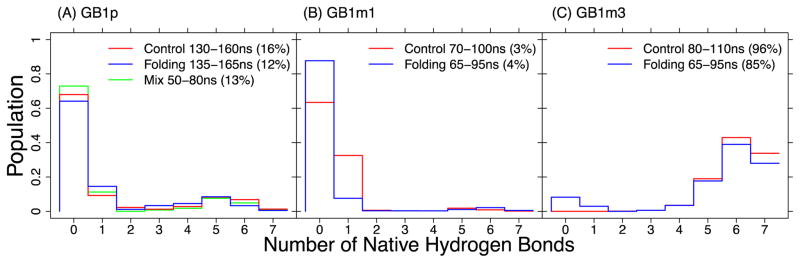

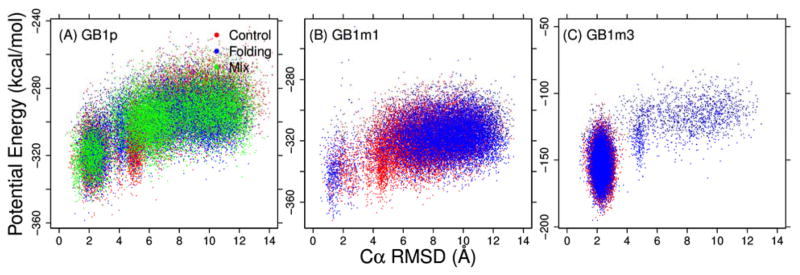

In Fig. 4, we examine the probability distributions of the number of native hydrogen bonds of the three GB1p-series of β-hairpins at 270 K derived from MSES simulations in the optimized GBMV2 force field. Importantly, MSES was able to drive many reversible folding transitions per 100 ns for all β-hairpins by coupling atomistic simulations with efficient Gō-like modeling (see Fig. S5). This is crucial for generating well-converged ensembles of β-hairpins that is essential for effective iterative backbone optimization. The RMSD between the distributions of native hydrogen bond formed derived from control and folding MSES runs are only 0.027, 0.116, and 0.038 for GB1p, GB1m1, and GB1m3, respectively. Nonetheless, we note that GB1p remains the most challenging sequence among three hairpins to simulate with a more flexible turn and thus requires the longest MSES runs to achieve satisfactory convergence (Fig. 4). The convergence of the GB1p structural ensemble was further confirmed by comparing to results derived from a third MSES run initiated from mixed folded and unfolded structures (green trace in Fig. 4A). The optimized GBMV2 force field successfully recapitulate the experimental order of stabilities for the three β-hairpins (GB1m3 > GB1p > GB1m1).50 Furthermore, the calculated stabilities are in excellent quantitative agreement with estimations from NMR for both GB1m1 (~4% vs 6%) and GB1m3 (~90% vs 86%), even though the stability of GB1p appears to be under-estimated (~14% vs ~42%). The ability to resolve the weakly populated folded state of GB1m1 is particularly encouraging (Fig. 4B), which is not possible using the previously optimized GBSW or GBSW/MS2 force fields.34 A strong correlation is present between the potential energy and RMSD for all three β-hairpins (Fig. 5). We note that it is in principle possible to increase the stability of GB1p to better match experimental results, either by manipulation of the effective backbone hydrogen-bonding strength, tweaking CMAP, or both. However, a better compromise across all model peptides could not be identified so far, partially due to computational cost of GBMV2. It is ~16 times slower than vacuum calculations for these small peptides, compared to only ~4.5-fold slow down for GBSW simulations.

Figure 4.

Probability distributions of the number of native backbone hydrogen bonds for (a) GB1p, (b) GB1m1, and (c) GB1m3. These distributions were calculated from structure ensembles extracted from the various segments of MSES simulations at T = 270 K. The number in the parentheses is the ratio of the folded population, identified as structures with ≥5 native backbone hydrogen bonds formed.

Figure 5.

Potential energy versus Cα RMSD for structure ensembles sampled at 270K from various MSES simulaitons of (A) GB1p, (B) GB1m1, and (C) GB1m3. Only conformationsl sampled during the last 30 ns are included.

We have further examined the ability of the optimized GBMV2 protein force field model to describe the unfolded state of proteins using Ala5. The results are summarized in Fig. S6 and Table S1. J coupling constants from simulated ensemble is comparable to the experimental values and probability distributions of all ϕ and ψ angles are similar to previous analysis of other force fields (Fig. S6). 51,34 The populations of α, β, and ppII regions using the GBMV2 force field are 11%, 49.6%, and 36.5%, respectively (Table S1), which appear to be highly comparable to the values derived from trajectories reweighted to best match the NMR scalar coupling constants.51 Nonetheless, the optimized GBMV2 force field seems to slightly overpopulate the β-region while under-populating the ppII region. This may be a consequence of the optimization strategy that focuses exclusively on the balance between α and β secondary structures. We have also examined the suitability of the optimized GBMV2 force field for simulating folded proteins. The results for protein A and protein G B1 domain are summarized in Fig. S11, confirming that

GBMV2 for atomistic simulations of IDP conformational ensembles

It is very encouraging that the optimized GBMV2 protein force field is able to recapitulate conformational equilibria of both helical and β-hairpin peptides. Previous applications of similarly optimized GBSW protein force field has suggested that this optimization strategy would likely lead to a high level of transferability,66, 69–71 even though GBSW did encounter formidable challenges when applied to larger systems.72–73 The later to a large extend could be attributed to limitations associated with the underlying vdW-like surface of GBSW, which GBMV2 is free of. Here, we evaluate the ability of the optimized GBMV2 force field to describe the disordered ensembles of three IDPs of various legnth and complexity. As discussed in the Introduction, a key common limitation of existing explicit and implicit solvent protein force fields is a strong and systematic bias towards generating overly compact conformations for unfolded protein states.

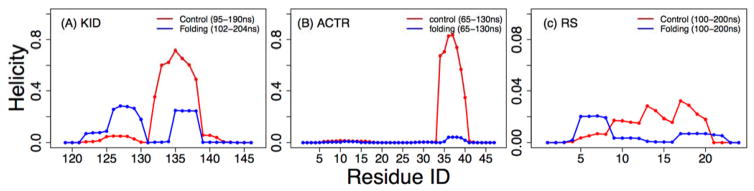

Convergence of the simulated ensembles was examined by comparing the distributions of various physical properties as well as principal components derived from independent folding and control MSES simulations. It is somewhat disappointing that the convergence appears to be quite limited for both KID and ACTR, which have complex and nontrivial conformational properties.65,72 For example, principlal component analysis (PCA) reveals that ensembles derived from control and folding simulations sample similar conformational space, but important differences persist even with ~200 ns and ~130 ns per replica MSES simulations for KID and ACTR, respectively (see Figs. S8–9). A high level of convergence was only achieved for the FS peptide, which has virtually no residual structures (see Fig. S10). Limited convergence is also evident when examining distributions allow various physical properties (e.g., see Figs. 6–7). This really highlights the significant challenges in generating well-converged conformational ensembles for even moderately sized IDPs. The difficulty of achieving high-level convergence here is related to the presence of desolvation peaks in implicit solvent with MS-like surfaces. It is also related to known limitations of using simple Cα-only Gō-like models for MSES simulations of IDPs, which are deficient in either generating local conformational fluctuations consistent with those at atomistic level or sampling alternative structures not already encoded in the Gō-potential.39 The later may be addressed by developing better CG models that maybe more appropriate for MSES simulations of IDPs.

Figure 6.

Residue helicity profiles of (A) KID, (B) ACTR, and (C) the RS peptide, calculated from structures sampled at 300 K during the second half of MSES simulations.

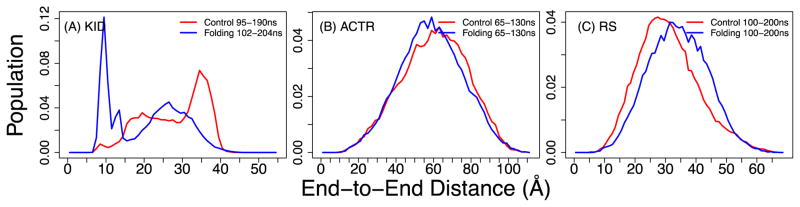

Figure 7.

Distributions of end-to-end distance for (A) KID, (B) ACTR, and (C) the RS peptide, calculated from structures sampled at 300 K during the second half of MSES simulations.

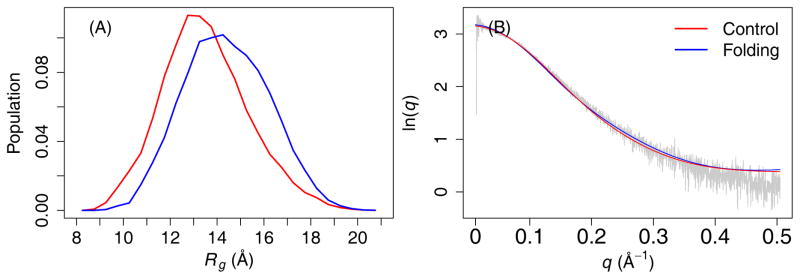

Despite the limited convergence achieved for KID and ACTR, the results appear to suggest that GBMV2 is likely suitable for accurate simulations of disordered protein ensembles. The predicted secondary structures appear to be consistent with previous experimental results, showing that KID has substantial residual helicity while ACTR and the RS peptide contains minimal residual helicities (Fig. 6). Importantly, examination of various biopolymer properties such as end-to-end distance and radius of gyration (Rg) demonstrate that the structural ensembles generated in the optimized GBMV2 force field are free of the over-compaction problem frequently associated with other explicit and implicit solvent force fields. As shown in Fig. 7, all three IDPs sample significant populations of rather extended conformations. The distributions for KID cover a wide range from up to ~45 Å (Fig. 7A), compared to much narrower range of up to ~25 Å for results derived from GBSW simulations.39, 74 For ACTR and RS peptide, the results show the smooth and continuous distributions (Fig. 7B and C), which can be expected for IDPs with minimal residual structures. The average Rg values of ACTR from both control and folding simulations are both around 23 Å at 270 K (Fig. S10), which compare well with the experimental value of ~26.3 Å at 278 K.75 Note that the experimental measurement was acquired on a longer ACTR construct with 71 residues compared to the 47-residue segment simulated here. For the RS peptide, the ensemble averaged Rg is around 13.5 and 14.6 Å for control and folding runs, respectively (Fig. 8A), which are slightly larger compared to ~12.6 Å derived from SAXS.13 We have also back-calculated the theoretical SAXS curves using CRYSOL76 and the result agree very well with the experimental curve13 (Fig. 8B). We also note that the simulated ensembles of the RS peptide contains less than 10% of left-handed α-helix (Table S2). Together these results suggest that the optimized GBMV2 force field is highly suitable for accurate atomistic simulations of IDPs and can be used to generate structural ensembles with realistic features on both secondary and tertiary levels.

Figure 8.

(A) Rg distribution of the RS peptide and (B) theoretical SAXS curves calculated from the structure ensemble. The experimental result is show in grey trace. The structure ensembles include all snapshots sampled at 298 K during the second half of MSES simulations.

Conclusion

We have revisited the optimization of the GBMV2/SA implicit solvent model, which is widely considered one of the best GB-class of models with a MS-like underlying solvent-solute boundary. The optimization mainly involved recursive tuning of key physical parameters, including the atomic input radii, for determining the location of the solvent-solute boundary, and the backbone torsion profiles, for balancing various local structural propensities. The optimization was guided by solvation free energies of peptide backbone and side chain analogs, PMFs of their pair-wise interactions, and importantly, conformational equilibria of carefully selected helical and β-hairpin model peptides. The last has been particularly challenging because of the computational cost of GBMV2 and slower conformational diffusion due to the presence of desolvation peaks associated with using MS-like surfaces. For this, we leveraged the greatly enhanced sampling efficiency of MSES to allow the calculation of well-converged structural ensembles of β-hairpin model peptides. The optimization was further facilitated by Hamiltonian mapping for efficient scanning of a large set of parameters and identification of optimal ones with only a few rounds of actual peptide simulations. The final optimized GBMV2 implicit solvent protein force field achieves greatly improved balance between solvation and protein-protein interactions and successfully recapitulates the conformational equilibria of all helical and β-hairpin model peptides. Furthermore, application to three IDPs of various lengths and complexities suggests that the optimized GBMV2 model is highly suitable for reliable atomistic simulations of disordered protein ensembles. In particular, it appears to be largely free of the over-compaction problem that has plagued many explicit solvent and implicit solvent protein force fields. Nonetheless, the current optimization was limited to SA-based treatment nonpolar solvation. It has been argued that both the length-scale dependence of hydrophobic solvation and solvent screening of dispersion interactions need to be incorporated in order to properly describe the conformational dependence of nonpolar solvation.26 Previous attempts to optimize such a nonpolar solvation model together with GBSW have not been successful (Chen, unpublished data), which may be attributed to limitations associated with the vdW-like surface defined in GBSW. It is likely that more advanced nonpolar solvation models combined with GBMV2 may provide further improvement in the ability to accurately describe the conformational equilibria of both stable and unstable proteins. This will be addressed in our future work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michal Feig and Michael Lee for helpful discussions regarding GBMV2. We are also grateful to Sarah Rauscher for sharing the experimental SAXS data on the RS peptide. This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM114300). The computing was performed using the Beocat cluster at Kansas State University (funded in part by NSF grants CNS-1006860, EPS-1006860, and EPS-0919443) and Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) facilities (TG-MCB140210).

References

- 1.Best RB, Zhu X, Shim J, Lopes PEM, Mittal J, Feig M, Mackerell AD., Jr Optimization of the Additive CHARMM All-Atom Protein Force Field Targeting Improved Sampling of the Backbone ϕ, ψ and Side-Chain χ 1and χ 2Dihedral Angles. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2012;8(9):3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Klepeis JL, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. PROTEINS: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2010;78(8):1950–1958. doi: 10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piana S, Lindorff-Larsen K, Shaw DE. How Robust Are Protein Folding Simulations with Respect to Force Field Parameterization? Biophysical Journal. 2011;100(9):L47–L49. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IMaier JA, Martinez C, Kasavajhala K, Wickstrom L, Hauser KE, Simmerling C. ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2015;11:3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Dror RO, Shaw DE. How fast-folding proteins fold. Science. 2011;334(6055):517–520. doi: 10.1126/science.1208351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane TJ, Shukla D, Beauchamp KA, Pande VS. Current Opinion In Structural Biology. Vol. 23. Elsevier Ltd; 2013. To milliseconds and beyond: challenges in the simulation of protein folding; pp. 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindorff-Larsen K, Trbovic N, Maragakis P, Piana S, Shaw DE. Structure and Dynamics of an Unfolded Protein Examined by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134(8):3787–3791. doi: 10.1021/ja209931w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skinner JJ, Yu W, Gichana EK, Baxa MC, Hinshaw JR, Freed KF, Sosnick TR. Benchmarking all-atom simulations using hydrogen exchange. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(45):15975–15980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404213111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Best RB, Zheng W, Mittal J. Balanced Protein–Water Interactions Improve Properties of Disordered Proteins and Non-Specific Protein Association. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2014;10(11):5113–5124. doi: 10.1021/ct500569b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriques J, Cragnell C, Skepö M. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Force Field Evaluation and Comparison with Experiment. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2015;11(7):3420–3431. doi: 10.1021/ct501178z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nerenberg PS, Head-Gordon T. Optimizing Protein–Solvent Force Fields to Reproduce Intrinsic Conformational Preferences of Model Peptides. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2011;7(4):1220–1230. doi: 10.1021/ct2000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palazzesi F, Prakash MK, Bonomi M, Barducci A. Accuracy of Current All-Atom Force-Fields in Modeling Protein Disordered States. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2015;11(1):2–7. doi: 10.1021/ct500718s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rauscher S, Gapsys V, Gajda MJ, Zweckstetter M, de Groot BL, Grubmüller H. Structural Ensembles of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Depend Strongly on Force Field: A Comparison to Experiment. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2015;11(11):5513–5524. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. Implicit Solvation Models: Equilibria, Structure, Spectra, and Dynamics. Chemical Reviews. 1999;99(8):2161–2200. doi: 10.1021/cr960149m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roux B, Simonson T. Implicit solvent models. Biophysical Chemistry. 1999;78(1–2):1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(98)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholls A, Honig B. A rapid finite difference algorithm, utilizing successive over-relaxation to solve the Poisson–Boltzmann equation. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1991;12(4):435–445. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bashford D, Case DA. Generalized born models of macromolecular solvation effects. Annual review of physical chemistry. 2000;51:129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.51.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feig M, Brooks CL., III Recent advances in the development and application of implicit solvent models in biomolecule simulations. Current Opinion In Structural Biology. 2004;14(2):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker NA. Improving implicit solvent simulations: a Poisson-centric view. Current Opinion In Structural Biology. 2005;15(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Brooks CL, III, Khandogin J. Recent advances in implicit solvent-based methods for biomolecular simulations. Current Opinion In Structural Biology. 2008;18(2):140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vitalis A, Pappu RV. ABSINTH: A new continuum solvation model for simulations of polypeptides in aqueous solutions. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2009;30(5):673–699. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Still WC, Tempczyk A, Hawley RC, Hendrickson T. Semianalytical treatment of solvation for molecular mechanics and dynamics. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1990;112(16):6127–6129. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onufriev A, Case DA, Bashford D. Effective Born radii in the generalized Born approximation: The importance of being perfect. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2002;23(14):1297–1304. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feig M, Onufriev A, Lee MS, Im W, Case DA, Brooks CL., III Performance comparison of generalized born and Poisson methods in the calculation of electrostatic solvation energies for protein structures. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25(2):265–284. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy RM, Zhang LY, Gallicchio E, Felts AK. On the Nonpolar Hydration Free Energy of Proteins: Surface Area and Continuum Solvent Models for the Solute-Solvent Interaction Energy. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125(31):9523–9530. doi: 10.1021/ja029833a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J, Brooks CL., III Implicit modeling of nonpolar solvation for simulating protein folding and conformational transitions. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2008;10:471–481. doi: 10.1039/b714141f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dzubiella J, Swanson JMJ, McCammon JA. Coupling Hydrophobicity, Dispersion, and Electrostatics in Continuum Solvent Models. Physical Review Letters. 2006;96(8):087802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.087802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z, Zhao S, Chun J, Thomas DG, Baker NA, Bates PW, Wei GW. Variational approach for nonpolar solvation analysis. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2012;137(8):084101. doi: 10.1063/1.4745084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Q, Luo R. A Poisson–Boltzmann dynamics method with nonperiodic boundary condition. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2003;119(21):11035. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson JMJ, Mongan J, McCammon JA. Limitations of Atom-Centered Dielectric Functions in Implicit Solvent Models. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2005;109(31):14769–14772. doi: 10.1021/jp052883s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pang X, Zhou HX. Poisson-Boltzmann Calculations: van der Waals or Molecular Surface? Communications in Computational Physics. 2013;13(01):1–12. doi: 10.4208/cicp.270711.140911s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee B, Richards FM. The Interpretation of Protein Stucutres: Estimation of Static Accessibility. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee MS, Feig M, Salsbury FR, Brooks CL., III New analytic approximation to the standard molecular volume definition and its application to generalized Born calculations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2003;24(11):1348–1356. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J. Effective Approximation of Molecular Volume Using Atom-Centered Dielectric Functions in Generalized Born Models. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2010;6(9):2790–2803. doi: 10.1021/ct100251y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight JL, Brooks CL., III Surveying implicit solvent models for estimating small molecule absolute hydration free energies. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2011;32(13):2909–2923. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chocholoušová J, Feig M. Balancing an accurate representation of the molecular surface in generalized born formalisms with integrator stability in molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2006;27(6):719–729. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Im W, Brooks CL., III Balancing Solvation and Intramolecular Interactions: Toward a Consistent Generalized Born Force Field. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128(11):3728–3736. doi: 10.1021/ja057216r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Chemical Physics Letters. Vol. 314. Elsevier; 1999. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding; pp. 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee KH, Chen J. Multiscale enhanced sampling of intrinsically disordered protein conformations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jcc.23957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W, Chen J. Accelerate Sampling in Atomistic Energy Landscapes Using Topology-Based Coarse-Grained Models. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2014;10(3):918–923. doi: 10.1021/ct500031v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugita Y, Kitao A, Okamoto Y. Multidimensional replica-exchange method for free-energy calculations. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2000;113:6042. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang J, Mackerell AD., Jr CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2013;34(25):2135–2145. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen H, Roe DR, Simmerling C. Improved Generalized Born Solvent Model Parameters for Protein Simulations. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2013;9(4):2020–2034. doi: 10.1021/ct3010485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen H, Maier J, Huang H, Perrone V, Simmerling C. Folding Simulations for Proteins with Diverse Topologies Are Accessible in Days with a Physics-Based Force Field and Implicit Solvent. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2014 doi: 10.1021/ja5032776. 140925104035005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Götz AW, Williamson MJ, Xu D, Poole D, Le Grand S, Walker RC. Routine Microsecond Molecular Dynamics Simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 1. Generalized Born. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2012;8(5):1542–1555. doi: 10.1021/ct200909j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirts MR, Pitera JW, Swope WC, Pande VS. Extremely precise free energy calculations of amino acid side chain analogs: Comparison of common molecular mechanics force fields for proteins. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2003;119(11):5740. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Best RB. Atomistic molecular simulations of protein folding. Current Opinion In Structural Biology. 2012;22(1):52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang J, Mackerell AD., Jr Induction of Peptide Bond Dipoles Drives Cooperative Helix Formation in the (AAQAA)3 Peptide. Biophysical Journal. 2014;107(4):991–997. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shalongo W, Dugad L, Stellwagen E. Distribution of Helicity within the Model Peptide Acetyl(AAQAA)3amide. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1994;116(18):8288–8293. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fesinmeyer RM, Hudson FM, Andersen NH. Enhanced Hairpin Stability through Loop Design: The Case of the Protein G B1 Domain Hairpin. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126(23):7238–7243. doi: 10.1021/ja0379520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Best RB, Buchete NV, Hummer G. Are Current Molecular Dynamics Force Fields too Helical? Biophysical Journal. 2008;95(1):L07–L09. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.132696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graf J, Nguyen PH, Stock G, Schwalbe H. Structure and Dynamics of the Homologous Series of Alanine Peptides: A Joint Molecular Dynamics/NMR Study. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(5):1179–1189. doi: 10.1021/ja0660406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karanicolas J, Brooks CL., III The origins of asymmetry in the folding transition states of protein L and protein G. Protein Science. 2002;11(10):2351–2361. doi: 10.1110/ps.0205402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feig M, Karanicolas J, Brooks CL., III MMTSB Tool Set: enhanced sampling and multiscale modeling methods for applications in structural biology. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling. 2004;22(5):377–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyazawa S, Jernigan RL. Residue – Residue Potentials with a Favorable Contact Pair Term and an Unfavorable High Packing Density Term, for Simulation and Threading. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1996;256(3):623–644. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1983;4(2):187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brooks BR, Brooks CL, III, Mackerell AD, Jr, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, Caves L, Cui Q, Dinner AR, Feig M, Fischer S, Gao J, Hodoscek M, Im W, Kuczera K, Lazaridis T, Ma J, Ovchinnikov V, Paci E, Pastor RW, Post CB, Pu JZ, Schaefer M, Tidor B, Venable RM, Woodcock HL, Wu X, Yang W, York DM, Karplus M. CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2009;30(10):1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: Molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. Journal of Computational Physics. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mackerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., III Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: Limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25(11):1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mackerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., III Improved Treatment of the Protein Backbone in Empirical Force Fields. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126(3):698–699. doi: 10.1021/ja036959e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Law SM, Ahlstrom LS, Panahi A, Brooks CL., III Hamiltonian Mapping Revisited: Calibrating Minimalist Models to Capture Molecular Recognition by Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2014;5(19):3441–3444. doi: 10.1021/jz501811k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Radhakrishnan I, Pérez-Alvarado GC, Parker D, Dyson HJ, Montminy MR, Wright PE. Solution structure of the KIX domain of CBP bound to the transactivation domain of CREB: a model for activator: coactivator interactions. Cell. 1997;91(6):741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Demarest SJ, Martinez-Yamout M, Chung J, Chen H, Xu W, Dyson HJ, Evans RM, Wright PE. Mutual synergistic folding in recruitment of CBP/p300 by p160 nuclear receptor coactivators. Nature. 2002;415(6871):549–553. doi: 10.1038/415549a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiang S, Gapsys V, Kim HY, Bessonov S, Hsiao HH, Möhlmann S, Klaukien V, Ficner R, Becker S, Urlaub H, Lührmann R, de Groot B, Zweckstetter M. Phosphorylation Drives a Dynamic Switch in Serine/Arginine-Rich Proteins. Structure. 2013;21(12):2162–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nehrbass U, Kern H, Mutvei A, Horstmann H. NSP1: a yeast nuclear envelope protein localized at the nuclear pores exerts its essential function by its carboxy-terminal domain. Cell. 1990 doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90063-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ganguly D, Chen J. Atomistic Details of the Disordered States of KID and pKID. Implications in Coupled Binding and Folding Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131(14):5214–5223. doi: 10.1021/ja808999m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Radhakrishnan I, Pérez-Alvarado GC, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Conformational preferences in the Ser< sup> 133</sup>-phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of the kinase inducible transactivation domain of CREB. FEBS letters. 1998;430(3):317–322. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00680-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen J, Brooks CL., III Critical Importance of Length-Scale Dependence in Implicit Modeling of Hydrophobic Interactions. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(9):2444–2445. doi: 10.1021/ja068383+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khandogin J, Chen J, Brooks CL., III Exploring atomistic details of pH-dependent peptide folding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(49):18546–18550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605216103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khandogin J, Brooks CL. Linking folding with aggregation in Alzheimer's beta-amyloid peptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(43):16880–16885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703832104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khandogin J, Raleigh DP, Brooks CL., III Folding Intermediate in the Villin Headpiece Domain Arises from Disruption of a N-Terminal Hydrogen-Bonded Network. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(11):3056–3057. doi: 10.1021/ja0688880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang W, Ganguly D, Chen J. Residual Structures, Conformational Fluctuations, and Electrostatic Interactions in the Synergistic Folding of Two Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. PLoS Computational Biology. 2012;8(1):e1002353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ganguly D, Chen J. Modulation of the Disordered Conformational Ensembles of the p53 Transactivation Domain by Cancer-Associated Mutations. PLoS Computational Biology. 2015;11(4):e1004247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang W, Chen J. Replica exchange with guided annealing for accelerated sampling of disordered protein conformations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2014;35(23):1682–1689. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kjaergaard M, Nørholm AB, Hendus-Altenburger R, Pedersen SF, Poulsen FM, Kragelund BB. Temperature-dependent structural changes in intrinsically disordered proteins: Formation of α-helices or loss of polyproline II? Protein Science. 2010;19(8):1555–1564. doi: 10.1002/pro.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. CRYSOL– a Program to Evaluate X-ray Solution Scattering of Biological Macromolecules from Atomic Coordinates. In. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 1995;28:768–773. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.