Abstract

Stopping violence against children is prioritized in goal 16 of the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015. All forms of child corporal punishment have been outlawed in 49 countries to date. Using data from 56,371 caregivers in eight countries that participated in UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, we examined change from Time 1 (2005–6) to Time 2 (2008–13) in national rates of corporal punishment of 2- to 14-year-old children and in caregivers’ beliefs regarding the necessity of using corporal punishment. One of the participating countries outlawed corporal punishment prior to Time 1 (Ukraine), one outlawed corporal punishment between Times 1 and 2 (Togo), two outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2 (Albania and Macedonia), and four have not outlawed corporal punishment as of 2016 (Central African Republic, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, and Sierra Leone). Rates of reported use of corporal punishment and belief in its necessity decreased over time in three countries; rates of reported use of severe corporal punishment decreased in four countries. Continuing use of corporal punishment and belief in the necessity of its use in some countries despite legal bans suggest that campaigns to promote awareness of legal bans and to educate parents regarding alternate forms of discipline are worthy of international attention and effort along with legal bans themselves.

Keywords: abuse, corporal punishment, laws, spanking

Protecting children against violence has become a major priority for international organizations as well as many governments and has been ensconced in major treaties such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which has been ratified by all countries in the world (except the United States). In the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, preventing violence against children is prioritized in target 16.2: End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children (Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, 2015a). The percentage of children aged 1 to 17 who experienced any physical punishment and/or psychological aggression by caregivers in the past month has been adopted by the United Nations as the indicator of achievement of SDG 16.2 (The Human Rights Guide to the SDGs, Danish Institute for Human Rights, p. 5).

In part response to these international efforts, as of 2016, 49 countries outlawed all forms of child corporal punishment, including by parents in the home (endcorporalpunishment.org). Although these legal bans represent progress for children in and of themselves by virtue of institutionalizing children’s right to protection, there is little comparative evidence across countries regarding changes over time in use of corporal punishment and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment in countries that have passed legal bans versus those that have not (see Bussmann, Erthal, & Schroth, 2011, for an exception).

Previous Evaluations of Legal Bans

The most systematic investigations of corporal punishment bans have been conducted in Sweden, the first country to outlaw corporal punishment (e.g., Durrant, 1999; Edfeldt, 1996; Janson, Långberg, & Svensson, 2011). Prior to the passing of the Swedish law banning corporal punishment in 1979, intermediary legal proceedings occurred over the course of decades of reform (such as removing in 1957 the section of the Penal Code that exempted parents from physical assault charges in disciplinary cases; Durrant & Janson, 2005). Swedish beliefs in the appropriateness of corporal punishment were already declining, enabling the ban to be passed in the first place (Edfeldt, 1996). The legal ban of corporal punishment was widely publicized (e.g., with announcements on milk cartons). These efforts seem to have been successful in promoting knowledge of the law. More than 90% of the Swedish population was aware of the law one year after it passed (Ziegert, 1983). After the legal ban, endorsement and use of corporal punishment continued to decline (Durrant, 1999). Further legal refinements also continued to reaffirm and extend the protection of children’s rights (Durrant & Janson, 2005). In Sweden, corporal punishment has been treated not just as its own discrete category of parenting behaviors but framed in the context of other humiliating treatment of children (Janson, Jernbro, & Långberg, 2011). Subsequent to implementing the ban, there have been lower rates of youth crime and suicide and less alcohol and drug use among youth than was the case prior to its implementation (Durrant, 2000). These trends offer reassurance that legal bans of spanking do not lead to out-of-control, poorly socialized youth.

Legal bans in other countries also have evolved over time, albeit without a common pattern of evolution. For example, although 1987 is generally identified as the year in which Norway outlawed corporal punishment, a court case in 2005 demonstrated that the 1987 law did not explicitly outlaw all corporal punishment; an explicit ban was not achieved until 2010 (Sandberg, 2011). Twenty-eight years after the 1983 legal ban in Finland (see Husa, 2011, for a review of legal reforms leading up to the ban), a representative sample of 4,609 15- to 80-year-olds reported whether they had been corporally punished. Those who were born after the legal ban were significantly less likely to have been slapped and beaten than those who were born before the legal ban, but there was no significant decline in corporal punishment in the 39 years prior to the legal ban, suggesting that the law itself marked a turning point (Österman, Björkqvist, & Wahlbeck, 2014). Nevertheless, even in Sweden and Finland with their longstanding legal bans, some parents continue to endorse and use corporal punishment. Such reluctance to embrace more child-centered approaches to discipline means that ongoing educational efforts are needed to continue to shape parents’ beliefs and behaviors (Ellonen, Jernbro, Janson, Tindberg, & Lucas, 2015).

Countries that have passed legal bans have been inconsistent with respect to their broader treatment of children’s rights and the extent to which changes in laws regarding corporal punishment have been publicized (Durrant & Smith, 2011). One year after Germany outlawed corporal punishment, for example, only 30% of German parents knew about the legal ban (Bussmann, 2004). It is unclear whether simply knowing that corporal punishment has been outlawed is sufficient to change parental beliefs and behaviors in the absence of public awareness campaigns and attempts to educate caregivers about alternative methods of discipline. Knowledge about the law as well as alternatives to using corporal punishment would seem to be precursors to changes in beliefs and behaviors. In New Zealand, which outlawed corporal punishment in 2007 (see D’Souza, Russell, Wood, Signal, & Elder, 2016, for a history and review of beliefs before and after the ban), a number of government programs and services (such as referrals to parenting programs) have been implemented to promote non-violent discipline. New Zealand police reports between 2007–2012 found no major issues with the enforcement of the law (Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, 2015b); although police investigated more child assaults after than before the ban, consistent with increased reporting, minor offenses were no more likely to be prosecuted after the ban (e.g., New Zealand Police, 2010).

In a study of five Western European countries (Austria, France, Germany, Spain, and Sweden; Bussmann et al., 2011), rates of corporal punishment varied both as a function of legal prohibition and presence of campaigns publicizing the negative effects of corporal punishment (which along with knowledge of the law and alternatives to using corporal punishment might be important to decreasing its use). The highest rates of corporal punishment were found in France, which had neither banned corporal punishment nor launched a public awareness campaign about the detriments of corporal punishment, followed by Spain, which had not outlawed corporal punishment at the time of the study but had launched national public awareness campaigns about the risks of violent childrearing (Bussmann et al., 2011). The lowest rates of corporal punishment were in Sweden (where corporal punishment has been illegal since 1979), followed by Germany (where the legal ban of corporal punishment was accompanied by a public awareness campaign) and Austria (where there was no public awareness campaign following the legal ban). The authors concluded that legal bans are more likely to change beliefs and behaviors than are public awareness campaigns about the negative effects of using corporal punishment, but that both legal bans and public awareness campaigns are important in reducing violence against children.

Public awareness campaigns have sometimes been deemed preferable to legal bans because of political reluctance to legislate government involvement in family life (Bussmann, 1996). Nevertheless, perceptions of particular behaviors as being violent are shaped by laws regarding their use. For example, individuals tend to judge a slap by a supervisor at work as being more violent than a parent slapping a child (Bussmann, 1996). Changing the law makes it harder to justify the use of violence in childrearing (Frehsee, 1996).

In a comparison of six European countries (Bulgaria, Germany, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Romania, and Turkey), parents were 1.7 times more likely to report using corporal punishment in countries in which corporal punishment is legal (duRivage et al., 2015). Zolotor and Puzia (2010) reviewed evidence from the first 24 countries that passed legal bans and concluded that legal bans were associated with decreases in support and use of corporal punishment. However, they noted that it was unclear whether the changes in support and use preceded or followed the legal bans. The authors also noted that 19 of the countries were in Europe and that all had representative or elected governments. The process of enacting legal bans on corporal punishment may be different in non-representative governments that have different ideas about individual rights (Zolotor & Puzia, 2010).

Historical and Legal Contexts of Corporal Punishment in the Eight Countries in the Present Study

The present study examines changes from Time 1 to Time 2 in caregivers’ reported use of corporal punishment and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment across eight diverse countries: Albania, Central African Republic, Kazakhstan, Macedonia, Montenegro, Sierra Leone, Togo, and Ukraine. In all eight, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has provided periodic reviews of the status of the protection of children’s rights and has evaluated whether each country explicitly prohibits corporal punishment of children at home, in schools, and in other settings (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/ for detailed reviews for each country). In four, corporal punishment has been explicitly outlawed in all settings, including at home; the remaining four countries do not yet prohibit corporal punishment in the home as of 2016. A brief review of the historical and legal contexts related to corporal punishment is provided for each country in turn.

Countries that outlawed corporal punishment by 2016

Albania

Corporal punishment in the home was outlawed in 2010. Article 21 of the Law on the Protection of the Rights of the Child 2010 states: “The child shall be protected from any form of … (a) physical and psychological violence, (b) corporal punishment and degrading and humiliating treatment….” Article 3(f) defines corporal punishment as: “any form of punishment resorting to the use of force aimed to cause pain or suffering, even in the slightest extent, by parents, siblings, grandparents, legal representative, relative or any other person legally responsible for the child.” Leading up to this law, corporal punishment in schools was outlawed in 1995. The Criminal Code of Albania was amended in 2008 to include imprisonment from three months to two years as punishment for “physical or psychological abuse of the child by the person who is obliged to care for him/her.” The Universal Periodic Review of Albania’s human rights record in 2014 confirmed that awareness campaigns about children’s rights are being carried out but also recommended more efficient implementation of the law prohibiting corporal punishment (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/albania.html).

Macedonia

Corporal punishment in the home was outlawed in 2013. Article 12(6) of the Law on Child Protection 2013 states that “The state and institutions are obliged to take all necessary measures to ensure the right of the children and prevent any form of discrimination or abuse regardless of the place where they are committed, the severity, intensity and duration.” In response to the Universal Periodic Review in 2014, the government confirmed that “The legislation prohibits corporal punishment of children. Article 9 of the Law on Child Protection prohibits psychological and physical ill-treatment, punishment or other inhumane treatment or abuse of children. Chapter XV of this Law contains misdemeanour provisions. Corporal punishment of children amounts to domestic violence, according to the Law on the Family and a crime according to the Criminal Code” (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/tfyr-macedonia.html).

Togo

Corporal punishment in the home was outlawed in 2007. Article 353 of the Children’s Code 2007 states that children are protected from “all forms of violence including sexual abuse, physical or mental injury or abuse, abandonment or neglect, and ill treatment by parents or by any other person having control or custody over him,” and Article 357 explicitly states that using corporal punishment is a punishable offense. In 2012, the Committee on the Rights of the Child expressed concern that, despite the legal prohibition, “corporal punishment remains socially accepted and widely practiced in schools and in the home.” The Committee recommended active measures to increase awareness about the negative effects of corporal punishment, to change beliefs about its acceptability, and to promote non-violent forms of discipline (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/togo.html).

Ukraine

Corporal punishment in the home was outlawed in 2004. Article 150(7) of the Family Code 2003 (in force 2004) states: “Physical punishment of the child by the parents, as well as other inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment are prohibited.” Prior to that, Article 10 of the Law on Protection of Childhood 2001 states “Every child is guaranteed the right to liberty, personal security and dignity. Discipline and order in the family, education and other children’s facilities should be provided on the principles based on mutual respect, justice and without humiliation of the honour and dignity of the child.” A 2011 review by the Committee on the Rights of the Child concluded that “awareness-raising campaigns and public education promoting positive and non-violent child-rearing” would be beneficial to ensure the effective implementation of the law to end corporal punishment (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/ukraine.html).

Countries that have not outlawed corporal punishment as of 2016

Central African Republic

As of 2016, corporal punishment has not been outlawed in the home or in other settings such as schools, daycares, or penal institutions. Article 580 of the Family Code 1997 states that parents have the authority “to reprimand and correct to the extent compatible with the age and level of understanding of the child.” Provisions against violence and abuse in other codes have not been interpreted as prohibiting corporal punishment in childrearing. The Committee on the Rights of the Child noted that corporal punishment in childrearing is widely accepted, and recommended that a clear change in law to prohibit all corporal punishment, however “light,” is needed (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/central-african-republic.html).

Kazakhstan

As of 2016, corporal punishment has not been outlawed in the home. Although the law in Kazakhstan does not give parents’ the “right” to use corporal punishment, corporal punishment also is not explicitly prohibited. The government reported to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child in 2003 that violence and corporal punishment are not allowed, but prohibition of corporal punishment is not instantiated in law. According to Article 60 of the Marriage and Family Code 2011, the child “has the right to be educated by the parents, ensuring its interests, full development and respect for human dignity.” Article 72 states that parents “do not have the right to harm the physical and mental health or moral development of the child” and that “methods of education must exclude neglectful, cruel, brutal or degrading treatment or abuse, humiliation or exploitation.” However, these statements do not explicitly prohibit all corporal punishment, however light (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/kazakhstan.html).

Montenegro

As of 2016, corporal punishment has not been outlawed in the home but has been outlawed in schools. In a report to the Human Rights Committee in October 2014, the government indicated that the National Plan of Action for Children 2013–2017 “envisages the implementation of at least three national campaigns to raise public awareness about the negative impact of corporal punishment of children in all settings” and that “there are plans for legislative amendments in order to explicitly define the prohibition of all forms of corporal punishment of children within the family” (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/montenegro.html).

Sierra Leone

As of 2016, corporal punishment has not been outlawed. Article 3 of the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act 1926 states: “Nothing in this Ordinance shall be construed to take away or affect the right of any parent, teacher or other person having the lawful control or charge of a child to administer punishment to such child.” In 2004 the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended the prohibition of corporal punishment in the home and at school, but this recommendation has not been enacted through legislation. The Child Rights Act 2007 confirmed the ideas of “reasonable” and “justifiable” punishment. According to the government’s report to the Universal Periodic Review in 2016, a newly formed Children’s Commission is working to eliminate corporal punishment (see http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/sierra-leone.html).

Beliefs and Behaviors

Attention to both beliefs about corporal punishment and reported use of corporal punishment is important because of evidence that beliefs about the effectiveness of corporal punishment can be powerful predictors of its use (Ateah & Durrant, 2005; Holden, Miller, & Harris, 1999). In a study of beliefs and behaviors of mothers and fathers in China, Colombia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, the Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States, parents who positively evaluated aggressive responses to child misbehaviors in hypothetical vignettes were more likely to report using corporal punishment with their own children one year later (Lansford et al., 2014). Interventions aimed at reducing parents’ use of corporal punishment often include componentsfocused on changing parents’ beliefs about the effectiveness and appropriateness of corporal punishment as a prelude to teaching them how to implement more child-friendly approaches to discipline (Holden, Brown, Baldwin, & Croft Caderao, 2014; Reich, Penner, Duncan, & Auger, 2012).

Theoretical Underpinnings and Hypotheses

Data collected in 2005–6 and again in 2008–13 from nationally representative samples in each of the eight countries were used to examine whether reported use of and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment changed from Time 1 to Time 2. Three theories of behavior change guided this work and suggest ways in which changing laws might change behaviors (World Bank, 2009). First, social cognitive theory holds that individuals’ behaviors are a function of both personal factors, such as self-control, and environmental factors, such as rewards or punishments (Bandura, 1986). Second, the theory of planned behavior suggests that individuals’ behaviors are dependent on intentions to behave in a particular way and that intentions are shaped by both subjective norms that reflect individuals’ perceptions of how they think others want them to behave as well as individuals’ own beliefs about the behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Armitage & Conner, 2001). Third, the trans-theoretical model of behavior change states that individuals progress through a series of six stages of behavior change. The first stage entails precontemplation, a period during which an individual has no intention to make a change in the near future. The process continues to the termination stage, a point at which the individual has changed behavior, feels efficacious in the enactment of the new behavior, and intends to maintain the new behavior (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997).

Each of these theories suggests that changing laws would change individuals’ behaviors because laws are a public instantiation of the collective beliefs of a society about the acceptability of a particular behavior (in this case using corporal punishment), because laws imply a set of rewards for adherence and punishment for non-adherence, and because laws can induce the motivation to change behavior to be compliant with the law. Thus, we expected countries that outlawed corporal punishment prior to Time 2 (i.e., Togo and Ukraine) to decline between Times 1 and 2 in rates of corporal punishment and caregivers’ belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment. We explored whether countries that outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2 or that have not yet outlawed corporal punishment also declined in rates of corporal punishment and caregivers’ belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment between Times 1 and 2.

Method

Data

UNICEF-supported Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) are nationally representative household surveys implemented mostly in low- and middle-income countries to generate internationally comparable data on key indicators of children’s well-being (UNICEF, 2006). Since the inception of the MICS in 1995, surveys have been conducted in more than 100 countries, through 5 rounds of data collection conducted at regular intervals (MICS1 to MICS5). Each country is responsible for designing and selecting a sample. However, the MICS technical global team provides strong recommendations on the following: the survey sample should be a probability sample in all stages of selection and designed in as simple a way as possible so that its field implementation can be easily and faithfully carried out with minimum opportunity for deviation from an overall standard design. The MICS is implemented using geographic stratification together with systematic probability proportionate to size (pps) sampling, which distributes the sample into each of a nation’s administrative subdivisions as well as its urban and rural sectors. Furthermore, a three-stage sample design is used. The first-stage, or primary sampling units (PSUs), is defined, if possible, as census enumeration areas, and they are selected with pps; the second stage is the selection of segments (clusters); and the third stage is the selection of the particular households within each segment that are to be interviewed in the survey (for further details see Bornstein, Putnick, Lansford, Deater-Deckard, & Bradley, 2016; UNICEF, 2006).

Data for the present study were from eight countries (Albania, Central African Republic, Kazakhstan, Macedonia, Montenegro, Sierra Leone, Togo, and Ukraine) that administered the child discipline module in two rounds of data collection (MICS3 in 2005–6, and either MICS4 or MICS5 in 2008–13). Only four countries of those included in the MICS had legal bans against corporal punishment and also had two waves of data available, so all of those countries were included. We then matched those four countries on the Human Development Index (HDI; a composite reflecting average life expectancy, school enrollment, literacy, and gross national income) and levels of corporal punishment reported in the 2005–6 MICS with countries that also had two waves of data available. The second round of data collection in Albania was conducted as part of the country’s 2008–2009 national Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), during which data on child discipline were collected using the standard MICS questions. None of these surveys was based on a panel design. That is, the same families were not interviewed at two time points. Instead, separate nationally representative samples were drawn in each country at each time point.

Four of the countries in the present study have outlawed corporal punishment as of 2016: Ukraine in 2004, Togo in 2007, Albania in 2010, and Macedonia in 2013. For Ukraine, data were collected in 2005 and 2012, providing an opportunity to examine change from the year after the legal ban to eight years after the ban. For Togo, data were collected in 2006 and 2010, providing an opportunity to assess changes in beliefs and behaviors from before to after the legal ban. Data were collected in 2005 and 2008–9 for Albania or 2011 for Macedonia, providing an opportunity to examine changes in beliefs and behaviors in the years leading up to these countries’ legal bans.

We also included four comparison countries that have not outlawed corporal punishment as of 2016 but are similar to the countries that have outlawed corporal punishment in other important respects as determined through analyses of comparable, nationally representative samples surveyed during the 2005–6 MICS (see Lansford & Deater-Deckard, 2012): Central African Republic, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, and Sierra Leone. Kazakhstan and Montenegro are similar to three of the countries that have recently outlawed corporal punishment (Albania, Macedonia, and Ukraine) in two important respects: all are classified as being countries high on the HDI (high HDI defined as HDI in the 51st to 75th percentile, United Nations Development Programme, 2010), and they historically have moderate rates of corporal punishment, fairly low rates of severe corporal punishment, and relatively low levels of conviction that using corporal punishment is essential to rearing a child properly based on analyses of the 2005–6 MICS (Lansford & Deater-Deckard, 2012). Like Togo where corporal punishment is banned, Central African Republic and Sierra Leone are low-HDI countries (defined as HDI in the lowest quartile, United Nations Development Programme, 2010) that historically have had high rates of corporal punishment, moderate rates of severe corporal punishment, and relatively greater belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment on the basis of the 2005–6 MICS (Lansford & Deater-Deckard, 2012).

Participants

Altogether 56,371 caregivers of target children between the ages of 2 and 14 years (M = 7.45, SD = 3.83; 50% girls) provided data during face-to-face interviews. Sample sizes, proportions of girls, average ages of children and caregivers, and country-level HDI are provided in Table 1, separately for each time point and country. In MICS3 only mothers or (if the mothers were deceased or not living in the household) primary caregivers responded to the questions in the discipline module. In MICS4–5, questions on discipline were administered to any adult in the household. To ensure comparability between the two rounds of data collection, we restricted the MICS4 and MICS5 sample to households in which the target child’s mother or primary caregiver responded to the discipline questions as in MICS3. If there was more than one eligible child between the ages of 2 and 14 years in the household, the interviewer used a standardized protocol to select randomly one target child from the household roster. Half of the respondents had no formal education or primary school education only; half had a secondary school education or higher.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Demographics by Country and Year

| Country and Year of Data Collection | n | Child Gender | Child Age | Caregiver Age | HDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % female | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Albania (corporal punishment outlawed in 2010) | .719 | ||||

| 2005 | 2370 | 46 | 8.77 (3.64) | 37.10 (9.02) | |

| 2008–9 | 2322 | 46 | 8.98 (3.72) | 39.18 (11.00) | |

| Central African Republic (corporal punishment not outlawed) | .315 | ||||

| 2006 | 7609 | 50 | 7.09 (3.67) | 38.05 (13.10) | |

| 2010 | 3444 | 53 | 6.97 (3.65) | 34.99 (12.87) | |

| Kazakhstan (corporal punishment not outlawed) | .714 | ||||

| 2006 | 6619 | 47 | 8.52 (3.90) | 39.75 (11.12) | |

| 2010–11 | 5052 | 49 | 7.64 (3.91) | 39.24 (11.62) | |

| Macedonia (corporal punishment outlawed in 2013) | .701 | ||||

| 2005 | 3265 | 50 | 5.80 (3.43) | 36.91 (11.94) | |

| 2011 | 1290 | 47 | 7.30 (3.92) | 36.95 (10.78) | |

| Montenegro (corporal punishment not outlawed) | .769 | ||||

| 2005 | 1131 | 47 | 7.04 (3.82) | 38.25 (11.32) | |

| 2013 | 657 | 49 | 7.20 (3.94) | 37.22 (10.35) | |

| Sierra Leone (corporal punishment not outlawed) | .317 | ||||

| 2005–6 | 5954 | 51 | 7.53 (3.64) | 43.72 (14.53) | |

| 2009–10 | 3880 | 55 | 7.77 (3.64) | 40.60 (14.93) | |

| Togo (corporal punishment outlawed in 2007) | .428 | ||||

| 2006 | 4473 | 51 | 8.06 (3.68) | N/A | |

| 2010 | 2003 | 53 | 7.56 (3.70) | 37.95 (13.69) | |

| Ukraine (corporal punishment outlawed in 2004) | .710 | ||||

| 2005 | 2752 | 49 | 6.17 (3.87) | 35.08 (10.99) | |

| 2012 | 3550 | 49 | 6.16 (3.75) | 37.08 (12.00) | |

Note. HDI = Human Development Index. These values were computed using the 2010 formula and were reported by the United Nations Development Programme (2010).

Measures

The 11 items in the Child Discipline module of the MICS were adapted from the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Finkelor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). Respondents were told, “All adults use certain methods to teach children the right behavior or address a behavior problem. I will read various methods that are used, and I want you to tell me whether you or anyone else in your household has used each method with (child’s name) in the last month.” The respondents then answered No (0) or Yes (1) to whether they or any other adults in their household had used each of six forms of corporal punishment. An additional item asked whether the respondents believed that to bring up/raise/educate the target child properly it is necessary to punish him or her physically. We constructed two indicators using UNICEF (2006) recommendations, which followed from the original scoring of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., 1998). The corporal punishment indicator reflected the proportion of children who were (a) spanked, hit, or slapped on the bottom with a bare hand; (b) hit or slapped on the hand, arm, or leg; (c) shaken; or (d) hit on the bottom or elsewhere on the body with an object. The severe corporal punishment indicator reflected the proportion of children who were (a) hit or slapped on the face, head, or ears; or (b) beaten over and over as hard as one could. These last two forms of corporal punishment were labelled “severe” because the first focuses on the child’s head, which is more fragile than the rest of the body, particularly for younger children, and because the second makes reference to high frequency (over and over) and intensity (as hard as one could). Each resulting dependent variable was binary, reflecting the proportions of adults in each country who reported believing it was necessary to use corporal punishment and who reported that their child had experienced corporal punishment or severe corporal punishment in the last month.

Analysis Plan

Given that the countries differed in terms of the timing of corporal punishment laws in relation to timing of data collection and had different time intervals between the first and second waves of data collection, we used a within-country rather than between-countries approach and considered individual countries’ patterns of change from Time 1 to Time 2. We used multivariate analyses of covariance (controlling for child age and child gender) to test change from Time 1 to Time 2 in the proportions of children in a country whose caregivers reporting using corporal punishment and severe corporal punishment and the proportions of caregivers who reported believing it was necessary to use corporal punishment. Because the sample sizes are so large, even small effects are likely to be statistically significant. To reduce the risk of Type I error, we used p < .001 rather than p < .05 as the threshold for determining statistical significance.

Results

As shown in Table 2, the countries varied widely on the proportions of caregivers who reported that their child had experienced corporal punishment in the last month (ranging from a low of .23 in Kazakhstan to a high of .76 in Sierra Leone at Time 1). The countries also varied on the proportions of caregivers who reported believing it was necessary to use corporal punishment to rear a child properly (ranging from a low of .05 in Montenegro to a high of .57 in Sierra Leone at Time 1).

Table 2.

Means (Standard Deviations) of Corporal Punishment by Country and Year

| Country and Year of Data Collection | Corporal Punishment | Severe Corporal Punishment | Belief in Need to Use Corporal Punishment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ukraine: Outlawed corporal punishment prior to Time 1 | |||

| 2005 | .37 (.48) | .02 (.14) | .14 (.34) |

| 2012 | .32 (.47) | .01 (.08) | .10 (.30) |

| Togo: Outlawed corporal punishment between Times 1 and 2 | |||

| 2006 | .72 (.45) | .26 (.44) | .33 (.47) |

| 2010 | .77 (.42) | .17 (.38) | .37 (.48) |

| Countries that outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2 | |||

| Albania | |||

| 2005 | .46 (.50) | .08 (.27) | .06 (.24) |

| 2008–9 | .63 (.48) | .19 (.39) | .15 (.36) |

| Macedonia | |||

| 2005 | .60 (.49)a | .17 (.38) | .08 (.27) |

| 2011 | .55 (.50) | .06 (.23) | .03 (.17) |

| Countries that have not outlawed corporal punishment as of 2016 | |||

| Central African Republic | |||

| 2006 | .75 (.44) | .33 (.47) | .26 (.44) |

| 2010 | .80 (.40) | .37 (.48) | .33 (.47) |

| Kazakhstan | |||

| 2006 | .23 (.42) | .01 (.09)a | .07 (.26)a |

| 2010–11 | .30 (.46) | .01 (.12) | .08 (.27) |

| Montenegro | |||

| 2005 | .45 (.50) | .06 (.23)a | .05 (.23)a |

| 2013 | .35 (.48) | .03 (.17) | .08 (.27) |

| Sierra Leone | |||

| 2005–6 | .76 (.43) | .23 (.42) | .57 (.50) |

| 2009–10 | .64 (.48) | .18 (.39) | .43 (.50) |

Note. Items were coded 0 = no, 1 = yes, so means can be interpreted as the proportion of respondents within each country who reported that their child experienced corporal punishment in the last month or who reported believing it is necessary to use corporal punishment to rear a child properly. Analyses control for child gender and child age.

Time 1 mean does not significantly differ from Time 2 mean in the same country, p > .001.

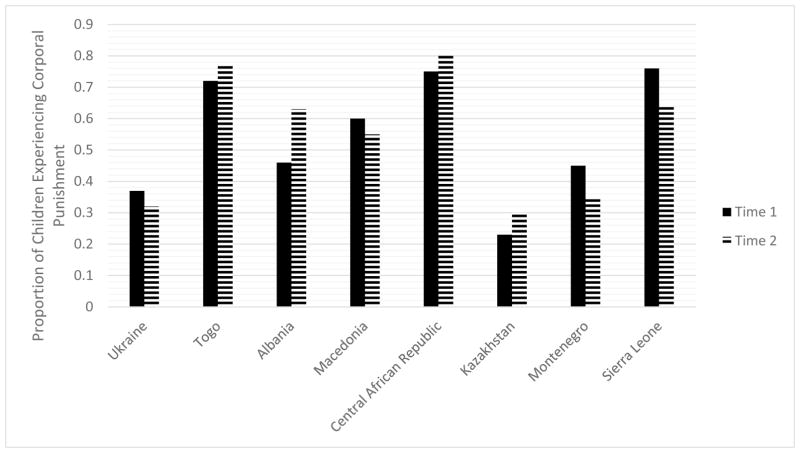

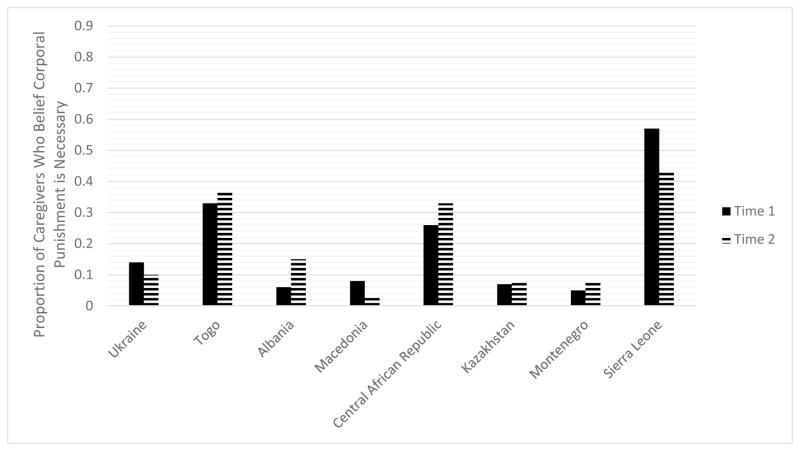

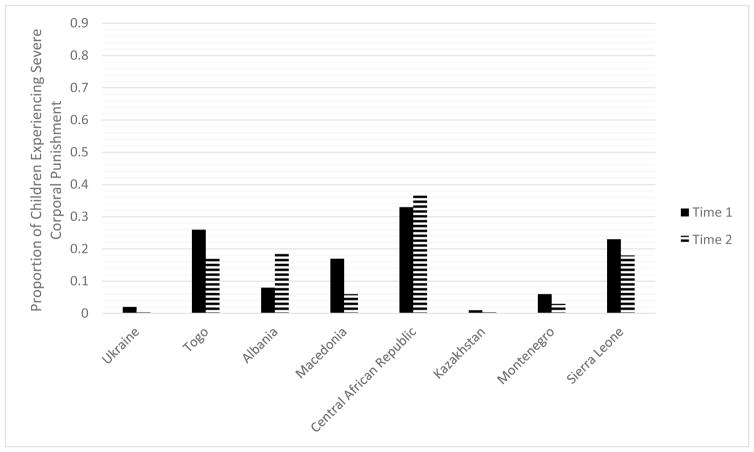

In all eight countries, there was a significant multivariate effect of time reflecting changes between Times 1 and 2 in reported use of corporal punishment and belief in its necessity (see Table 3 and Figures 1–3). In Ukraine, which outlawed corporal punishment prior to Time 1, rates of corporal punishment as well as belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment declined between Times 1 and 2. In Togo, which outlawed corporal punishment between Times 1 and 2, reported rates of corporal punishment use and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment increased, although rates of severe corporal punishment decreased. In Albania, which outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2, rates of corporal punishment, severe corporal punishment, and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment increased, suggesting that the use of corporal punishment was not declining prior to the legal ban. Macedonia, which also outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2, however, showed declines in rates of severe corporal punishment and in beliefs regarding the necessity of corporal punishment in the years leading up to the legal ban (reported use of milder forms of corporal punishment remained unchanged).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analyses of Covariance to Test Change from Time 1 to Time 2

| Country | Corporal Punishment F | Severe Corporal Punishment F | Belief in Need to Use Corporal Punishment F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ukraine: Outlawed corporal punishment prior to Time 1 | |||

| Pillai’s F(3, 6296) = 14.15 | 15.98 | 22.63 | 17.58 |

| Togo: Outlawed corporal punishment between Times 1 and 2 | |||

| Pillai’s F(3, 6470) = 37.46 | 14.47 | 59.50 | 12.45 |

| Countries that outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2 | |||

| Albania | |||

| Pillai’s F(3, 4686) = 84.52 | 149.90 | 121.10 | 110.70 |

| Macedonia | |||

| Pillai’s F(3, 4549) = 43.22 | 5.97a | 115.12 | 31.30 |

| Countries that have not outlawed corporal punishment as of 2016 | |||

| Central African Republic | |||

| Pillai’s F(3, 11,047) = 31.60 | 40.73 | 20.02 | 68.70 |

| Kazakhstan | |||

| Pillai’s F(3, 11,665) = 23.06 | 65.37 | 6.96a | .91a |

| Montenegro | |||

| Pillai’s F(3, 1782) = 10.37 | 15.90 | 7.46a | 3.70a |

| Sierra Leone | |||

| Pillai’s F(3, 9828) = 88.10 | 164.97 | 28.43 | 163.64 |

Note. Analyses controlled for child age and child gender.

Time 1 mean does not significantly differ from Time 2 mean in the same country, p > .001.

Figure 1.

Change over time in the proportion of children who experience corporal punishment. Ukraine outlawed corporal punishment prior to Time 1; Togo outlawed corporal punishment between Times 1 and 2; Albania and Macedonia outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2; Central African Republic, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, and Sierra Leone have not yet outlawed corporal punishment. Within-country differences between Time 1 and Time 2 were all significant at p < .001 except in Macedonia.

Figure 3.

Change over time in the proportion of caregivers who believe in the necessity of using corporal punishment. Ukraine outlawed corporal punishment prior to Time 1; Togo outlawed corporal punishment between Times 1 and 2; Albania and Macedonia outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2; Central African Republic, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, and Sierra Leone have not yet outlawed corporal punishment. Within-country differences between Time 1 and Time 2 were all significant at p < .001 except in Kazakhstan and Montenegro.

In the remaining four countries, corporal punishment has not been outlawed as of 2016. In the Central African Republic, rates of corporal punishment, severe corporal punishment, and the belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment all increased from Time 1 to 2. In Kazakhstan, reported use of corporal punishment also increased (although reported rates of severe corporal punishment use and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment remained unchanged). In contrast, in Montenegro reported use of corporal punishment decreased (but reported rates of severe corporal punishment and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment remained unchanged). Finally, in Sierra Leone, reported use of corporal punishment and severe corporal punishment and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment all decreased from Time 1 to Time 2.

Discussion

Reported rates of use of corporal punishment and belief in its necessity decreased over time in three countries; rates of use of severe corporal punishment decreased in four countries. Specific patterns of findings within countries varied, perhaps as a function of differences in the timing of corporal punishment bans in relation to the timing of data collection as well as differences across countries in steps that might have been taken to publicize the bans and educate parents about alternate forms of discipline. Although legal bans on corporal punishment are an important step in promoting children’s right to protection from abuse, bans alone may not be sufficient to change beliefs and behaviors unless combined with public awareness campaigns to publicize the bans and educational materials to provide parents with alternate means of discipline. In countries that have outlawed corporal punishment, public awareness campaigns regarding the change in laws have ranged from virtually nothing to extensive campaigns that continue even years after the bans (Durrant & Smith, 2011). Therefore, it makes sense that we found variation in national rates of corporal punishment and belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment not just as a function of legal bans but also in ways that appeared unique for particular countries.

Even in Kazakhstan and Montenegro, which as of 2016 have not outlawed corporal punishment, reported use of corporal punishment and belief in its necessity were less prevalent than in Togo, which outlawed corporal punishment yet remains a country characterized by many risks for children, including high rates of childhood morbidity and mortality (UNICEF, 2015). Historically, once countries made considerable progress in promoting children’s survival, they have turned more to efforts to promote children’s psychosocial development (Jensen et al., 2015). Perhaps as a consequence of international efforts to support children’s well-being, this model has been changing over time, with efforts to promote children’s survival and development increasingly integrated, even in low-income countries (UNICEF, 2013). In addition, analyses of how a variety of laws spreads internationally suggest that policy makers tend to introduce new laws adapted from countries that are familiar and similar, perhaps by virtue of geographic or cultural proximity (Linos, 2013).

The importance of including interventions aimed at changing beliefs and providing education about alternatives to corporal punishment is illustrated in a study of Kenyan teachers eight years after the Kenyan government banned corporal punishment in schools. Although the teachers were aware of the law, they continued to use corporal punishment because they believed it was the most effective way to discipline children (Mweru, 2010). In reviewing the history and context of the legal ban of corporal punishment in Sweden, Durrant (2003) noted that the ban was meant to be educational rather than punitive. Prior to the legal ban on corporal punishment, children already had the same protections against assault as adults. In effect, the legal ban on corporal punishment did not create a new crime but instead was meant to communicate clearly to parents that chastisement was not an acceptable way of bringing up children (Durrant, 2003). Countries may differ in legal consequences associated with using corporal punishment after it is outlawed, and these differences in legal consequences might account for differences in effects of the bans. The three theoretical models of behavior change that guided our study (Ajzen, 1991; Bandura, 1986; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997) suggest that laws induce behavior change because they function as a public instantiation of societal beliefs about the appropriateness of a particular behavior and because they involve a set of rewards and punishments for behaving in accordance with the law (or not). The pattern of decreasing reported use of corporal punishment and belief in its necessity from Time 1 to Time 2 in Ukraine supports this theoretical expectation regarding behavior change following the outlawing of corporal punishment, as did the pattern of findings in Togo showing a decrease in the reported use of severe corporal punishment from Time 1 to Time 2. The pattern of findings in Togo with respect to milder forms of corporal punishment and belief in its necessity was not consistent with expectations derived from the theoretical models, though.

Recognizing that changing the law is not always sufficient to change behavior, a number of public awareness campaigns have been developed to promote awareness of laws involving corporal punishment, to impart knowledge regarding the negative effects of corporal punishment, and to build capacity in using non-violent forms of discipline (see Durrant & Smith, 2011, for several examples). In addition, many parenting interventions have incorporated components designed to change beliefs and behaviors related to corporal punishment and alternate forms of discipline (Holden et al., 2014; Reich et al., 2012). Using these kinds of public awareness and intervention programs in conjunction with legal changes appears to offer the most success for changes in beliefs and behaviors (Bussmann et al., 2011). Changing the law may be enough to change individuals’ expectations regarding punishments for using corporal punishment (a necessary component of environmental contingencies according to social cognitive theory, Bandura, 1986) and perceptions of norms regarding other people’s expectations (as outlined in the theory of planned behavior, Ajzen, 1991; Armitage & Conner, 2001). The use of public awareness campaigns and interventions may help to promote changes in individuals’ own beliefs about corporal punishment (another component of the theory of planned behavior) and to move individuals toward later stages of behavior change outlined in the trans-theoretical model of behavior change (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997), such as feeling efficacious about using nonviolent forms of discipline.

Strengths and Limitations

Important strengths of this study include the large, nationally representative samples of families from eight low- and middle-income countries that supplied data at two points in time, making it possible to examine change from Time 1 to Time 2 in national rates of reported use of and beliefs in the necessity of using corporal punishment. At least five limitations also should be noted. First, because caregiver respondents were asked to report on whether any adults in their household used corporal punishment with the target child in the last month, the reports may be underestimates given that some respondents may be unaware of the behavior of other household members or they were unwilling to admit using corporal punishment. However, this bias would not affect the comparison between national rates at the two time points. Second, caregivers’ belief in the necessity of using corporal punishment was assessed with a single item that did not take into account nuances of factors affecting caregivers’ endorsement of corporal punishment with particular children or in certain situations. Likewise, the set of items that asked about the use of different forms of corporal punishment in the last month did not assess more fine-grained frequencies and was not exhaustive. For example, caregivers may have used other forms of corporal punishment (e.g., hot sauce on the tongue, kneeling on grains of rice) that were not assessed. Third, systematic information about efforts to publicize the bans and efforts to educate parents about alternative forms of discipline was not available. Future research would benefit from such information to examine these factors as predictors, in conjunction with laws, of caregivers’ beliefs and behaviors. Fourth, the intervals between the first and second waves of data collection ranged from as few as three years to as many as eight years; there is more opportunity for changes in beliefs and behaviors over the course of eight than three years. Fifth, data were available both before and after the legal ban of corporal punishment in only one of the eight countries (Togo). Although important information can be gleaned from the other countries with respect to changes in beliefs and behaviors leading up to legal bans (in the case of Albania and Macedonia) and changes from one to eight years after the legal ban (in the case of Ukraine), data from before and after legal bans in additional countries will be important for future research that can treat the change in law as an intervention in comparison to control groups of countries that have not outlawed corporal punishment. Given these limitations, caution should be used in applying the findings as a basis for policy making.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Political scientists have found that when the same law is implemented by many countries and an international organization supports the law as the dominant international model, the influence of foreign laws on an individual country’s law is likely to be strong (Linos, 2013). This appears to be the current situation with respect to laws prohibiting corporal punishment, with 49 countries currently outlawing corporal punishment in all settings and international organizations advocating for such legal bans (United Nations, 2015). The challenges going forward are twofold. First, although 49 countries is a start in the course of universal banishment of corporal punishment, most countries in the world still have not outlawed corporal punishment in the home. Second, even for countries that have outlawed corporal punishment, many caregivers continue to believe that it is necessary to use corporal punishment and even more report that their children continue to experience corporal punishment. Therefore, campaigns to promote awareness of legal bans and to educate parents regarding alternate forms of discipline are worthy of international attention and effort along with legal bans themselves.

Figure 2.

Change over time in the proportion of children who experience severe corporal punishment. Ukraine outlawed corporal punishment prior to Time 1; Togo outlawed corporal punishment between Times 1 and 2; Albania and Macedonia outlawed corporal punishment after Time 2; Central African Republic, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, and Sierra Leone have not yet outlawed corporal punishment. Within-country differences between Time 1 and Time 2 were all significant at p < .001 except in Kazakhstan and Montenegro.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage C, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateah CA, Durrant JE. Maternal use of physical punishment in response to child misbehavior: Implications for child abuse prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:169–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Bradley RH. Gender in low- and middle-income countries. Monograph of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2016;81(1) doi: 10.1111/mono.12223. Serial No. 320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann K-D. Changes in family sanctioning styles and the impact of abolishing corporal punishment. In: Frehsee D, Horn W, Bussmann K-D, editors. Violence against children in the family. Berlin: de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann KD. Evaluating the subtle impact of a ban on corporal punishment of children in Germany. Child Abuse Review. 2004;13:292–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann K-D, Erthal C, Schroth A. Effects of banning corporal punishment in Europe: A five-nation comparison. In: Durrant JE, Smith AB, editors. Global pathways to abolishing physical punishment: Realizing children’s rights. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011. pp. 299–322. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza AJ, Russell M, Wood B, Signal L, Elder D. Attitudes to physical punishment of children are changing. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2016 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310119. Published Online First. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- duRivage N, Keyes K, Leray E, Pez O, Bitfoi A, Koç C, … Kovess-Masfety V. Parental use of corporal punishment in Europe: Intersection between public health and policy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0118059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE. Evaluating the success of Sweden’s corporal punishment ban. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:435–448. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE. Trends in youth crime and well-being in Sweden since the abolition of corporal punishment. Youth and Society. 2000;31:437–455. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE. Legal reform and attitudes toward physical punishment in Sweden. International Journal of Children's Rights. 2003;11:147–174. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE, Janson S. Legal reform, corporal punishment and child abuse: The case of Sweden. International Review of Victimology. 2005;12:139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE, Smith AB, editors. Global pathways to abolishing physical punishment: Realizing children’s rights. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Edfeldt ÅW. The Swedish 1979 Aga ban plus fifteen. In: Frehsee D, Horn W, Bussmann K-D, editors. Family violence against children: A challenge for society. Berlin: de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ellonen N, Jernbro C, Janson S, Tindberg Y, Lucas S. Current parental attitudes towards upbringing practices in Finland and Sweden 30 years after the ban on corporal punishment. Child Abuse Review. 2015;24:409–417. [Google Scholar]

- Frehsee D. Violence toward children in the family and the role of law. In: Frehsee D, Horn W, Bussmann K-D, editors. Violence against children in the family. Berlin: de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. [Accessed January 15, 2016];Ending violent punishment of children – a foundation of a world free from fear and violence. 2015a Available http://endcorporalpunishment.org/assets/pdfs/briefings-thematic/SDG-indicators-on-violent-punishment-briefing.pdf.

- Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. [Accessed May 11, 2016];Country report for New Zealand. 2015b Available http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/country-reports/new-zealand.html.

- Holden GW, Brown AS, Baldwin AS, Croft Caderao K. Research findings can change attitudes about corporal punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:902–908. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Miller PC, Harris SD. The instrumental side of corporal punishment: Parents’ reported practices and outcome expectancies. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:908–919. [Google Scholar]

- Husa S. Finland: Children’s right to protection. In: Durrant JE, Smith AB, editors. Global pathways to abolishing physical punishment: Realizing children's rights. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011. pp. 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Janson S, Jernbro C, Långberg B. Corporal punishment and other humiliating behavior towards children in Sweden: A national study 2011. Stockholm: Stiftelsen Allmäanna Barnhuset; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Janson S, Långberg B, Svensson B. Sweden: A 30-year ban on physical punishment of children. In: Durrant JE, Smith AB, editors. Global pathways to abolishing physical punishment: Realizing children's rights. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011. pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SK, Bouhouch RR, Walson JL, Daelmans B, Bahl R, Darmstadt GL, Dua T. Enhancing the child survival agenda to promote, protect, and support early child development. Seminars in Perinatology. 2015;39:373–386. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K. Childrearing discipline and violence in developing countries. Child Development. 2012;83:62–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Woodlief D, Malone PS, Oburu P, Pastorelli C, Skinner AT, … Dodge KA. A longitudinal examination of mothers’ and fathers’ social information processing biases and harsh discipline in nine countries. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:561–573. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linos K. The democratic foundations of policy diffusion: How health, family, and employment laws spread across countries. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mweru M. Why are Kenyan teachers still using corporal punishment eight years after a ban on corporal punishment? Child Abuse Review. 2010;19:248–258. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Police. [Accessed August 11, 2016];6th review of police activity since enactment of the Crimes (substituted section 59) Amendment Act 2007. 2010 Available www.police.govt.nz/sites/default/files/resources/s59_6th_review_web%20_report.pdf.

- Österman K, Björkqvist K, Wahlbeck K. Twenty-eight years after the complete ban on the physical punishment of children in Finland: Trends and psychosocial concomitants. Aggressive Behavior. 2014;40:568–581. doi: 10.1002/ab.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich SM, Penner EK, Duncan GJ, Auger A. Using baby books to change new mothers’ attitudes about corporal punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg K. Norway: The long and winding road towards prohibiting physical punishment. In: Durrant JE, Smith AB, editors. Global pathways to abolishing physical punishment: Realizing children's rights. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011. pp. 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. (UNDP) [May 19, 2016];The real wealth of nations: Pathways to human development. 2010 Available at http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/270/hdr_2010_en_complete_reprint.pdf.

- UNICEF. [Accessed January 15, 2016];Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey manual 2005: Monitoring the situation of children and women. 2006 Available at: http://www.childinfo.org/files/Multiple_Indicator_Cluster_Survey_Manual_2005.pdf.

- UNICEF. [Accessed January 15, 2016];Young child survival and development. 2013 Available at http://www.unicef.org/publicpartnerships/files/Young_Child_Survival_and_Development_2013_Thematic_Report.pdf.

- UNICEF. [Accessed January 15, 2016];The state of the world’s children 2015. 2015 Available at http://sowc2015.unicef.org/

- United Nations. [Accessed December 14, 2015];Ending corporal punishment of children. 2015 Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/CorporalPunishment.aspx.

- World Bank. [Accessed May 10, 2016];Theories of behavior change. 2009 Available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTGOVACC/Resources/BehaviorChangeweb.pdf.

- Ziegert KA. The Swedish prohibition of corporal punishment: A preliminary report. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1983;45:917–926. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor AJ, Puzia ME. Bans against corporal punishment: A systematic review of the laws, changes in attitudes and behaviors. Child Abuse Review. 2010;19:229–247. [Google Scholar]