Summary

Induction of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) that target HIV-1 envelope (Env) is a goal of HIV-1 vaccine development. A bnAb target is the Env third variable loop (V3)-glycan site. To determine if immunization could induce antibodies to the V3-glycan bnAb binding site, we repetitively immunized macaques over a three-year period with an Env expressing V3-high mannose glycans. Env immunizations elicited plasma antibodies that neutralized HIV-1 expressing only high mannose glycans– a characteristic shared by early bnAb B cell lineage members. A rhesus recombinant monoclonal antibody from a vaccinated macaque bound to the V3-glycan site at the same amino acids as broadly neutralizing antibodies. A structure of the antibody bound to glycan revealed the three variable heavy chain complementarity determining regions formed a cavity into which glycan could insert and neutralized multiple HIV-1 isolates with high mannose glycans. Thus, HIV-1 Env vaccination induced mannose-dependent antibodies with characteristics of V3-glycan bnAb precursors.

Keywords: HIV, V3 glycan, vaccination, glycan, long-term immunization

eTOC

Most bnAb epitopes on HIV-1 Envelope include host glycans, but previous Env vaccines have not induced glycan-dependent antibodies. Saunders et al. describe here the ontogeny, crystal structure with glycan, and virion Man9GlcNAc2 -dependent neutralization for glycan-reactive antibodies induced by envelope vaccination.

Introduction

Development of an effective HIV-1 vaccine is a major goal of HIV-1 prevention strategies (Fauci and Marston, 2014). One objective for a HIV-1 vaccine is to elicit broadly reactive neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs; Burton et al., 2012; Mascola and Haynes, 2013; Mascola and Montefiori, 2010). Broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 results from antibodies binding to virion-associated trimeric envelope (Env) glycoproteins (Corti and Lanzavecchia, 2013; Parren and Burton, 2001). HIV-1 Env is densely coated with host glycans that provide both a shield against, and a target for, immune recognition (Doores, 2015; Leonard et al., 1990; Scanlan et al., 2007a; Wei et al., 2003). Most gp120 bnAb epitopes include contacts with glycans (Blattner et al., 2014; Doria-Rose et al., 2014; Garces et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2013; McLellan et al., 2011; Pancera et al., 2014; Pejchal et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2013), yet Env glycans in the setting of vaccination are poorly immunogenic (Astronomo et al., 2010; Astronomo et al., 2008; Doores et al., 2010b; Wang et al., 2008). Recent vaccine studies in monkeys, rabbits and transgenic mice have shown that the presence of glycans alters viral neutralization sensitivity from potently neutralized to resistant (Bradley et al., 2016; Crooks et al., 2015; McCoy et al., 2016; Sanders et al., 2015; Tian et al., 2016). Thus, recognition of Env glycans is a major hurdle to HIV-1 vaccine development.

One conserved broadly neutralizing epitope on Env is a patch of high mannose glycans surrounding the V3 loop (Kong et al., 2013). Human monoclonal bnAbs against the V3-glycan Env site have been isolated from HIV-1-infected individuals, including PGT121, PGT135, and PGT128 that bind N-linked glycans near the V3 loop as well as make contacts with adjacent amino acids (Walker et al., 2011). 2G12 is a neutralizing antibody isolated from natural infection that binds to Env by contacting only the glycans proximal to the V3 loop (Murin et al., 2014). Glycan-targeted antibodies are of particular interest since they are among the most potent bnAbs (Walker et al., 2011), and protect against chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) infection in macaques at low plasma concentrations (Moldt et al., 2012).

Here we vaccinated rhesus macaques with a group M consensus Env (M.CON-S gp140CFI) bearing Man9GlcNAc2 high mannose glycans on the asparagine at 301 (N301) and the asparagine at 332 (N332) within the V3-glycan site (Go et al., 2008). We show that Env vaccination induced antibodies that blocked the binding of the HIV-1 Env glycan-targeting bnAb 2G12 in 10 of 10 vaccinated macaques, and elicited plasma neutralizing antibodies for viruses with high density Man9GlcNAc2 glycans in 6 of 10 macaques. We report the isolation of a vaccine-induced recombinant Man9GlcNAc2-dependent neutralizing antibody B cell clonal lineage (DH501) that recognized the V3-glycan bnAb epitope, and show that both DH501 and V3-glycan bnAb lineage precursors demonstrate Man9GlcNAc2-dependent neutralization.

Results

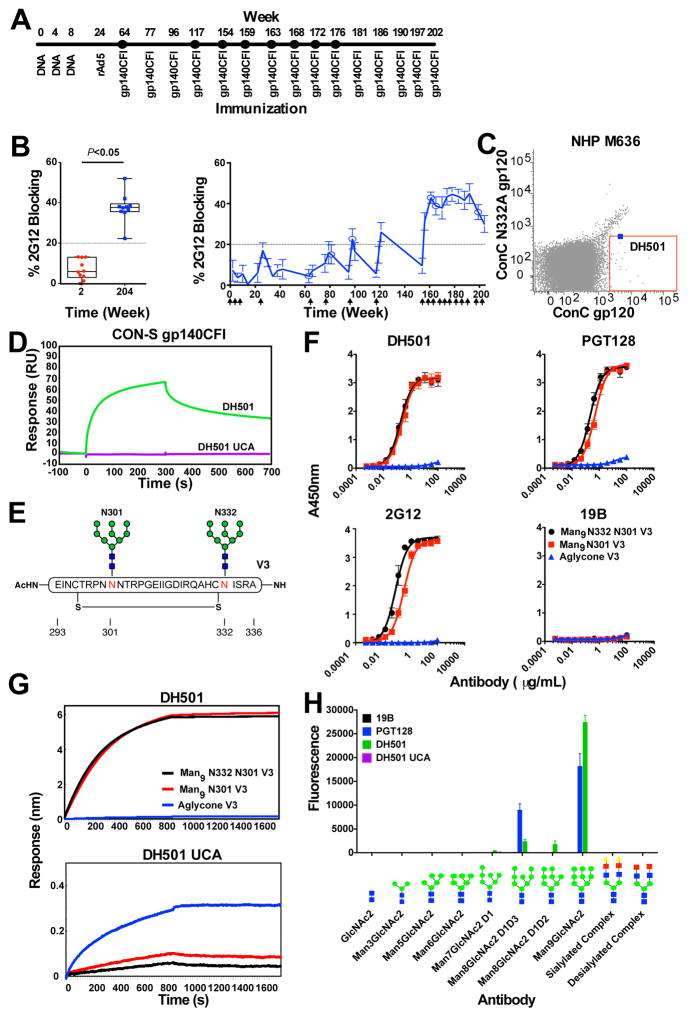

Induction of glycan bnAb-blocking antibodies

V3-glycan bnAbs develop in HIV-1-infected individuals only after years of infection (Bonsignori et al., 2017; Doria-Rose et al., 2009; Gray et al., 2011; MacLeod et al., 2016; Sather et al., 2009; Simek et al., 2009; Simonich et al., 2016). We asked if vaccination over a long duration of time with an Env immunogen with N301 and N332 high mannose glycans (Figure S1A and S1B; Go et al., 2008; Liao et al., 2013b) could elicit glycan-dependent antibodies. CON-S gp140CFI was chosen for the vaccination since it is glycosylated at the V3 glycan sites with higher percentages of high mannose glycans than other 293 cell line-derived recombinant Envs such as JR-FL gp140CF (Go et al., 2008). We vaccinated ten rhesus macaques with plasmid DNA encoding M.CON-S gp145, boosted with a recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 viral vector encoding M.CON-S gp145, and further boosted with gp140CFI protein 15 times over 204 weeks (Figure 1A and S1C). We examined plasma antibody responses for their ability to block HIV-1 Env binding of bnAbs 2G12, PGT125, and PGT128 that are dependent on the N-linked glycan at N332 for binding (Figure 1B and S1D). Antibodies that blocked the binding of 2G12 developed in 10 of 10 animals by week 204 after 15 M.CON-S gp140CFI glycoprotein immunizations (Figure 1B). PGT125 and PGT128 bnAbs were similarly blocked by immune plasma (Figure S1D). However, both PGT125 and PGT128 were blocked by V3 loop linear peptide monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) 19B and 447-52D (Figure S1E), and thus, the PGT125 and PGT128 plasma blocking assays were not specific for V3-glycan epitope antibodies. Linear V3 loop antibodies were elicited in the macaques (Figure S1F), thus the PGT128 blocking could be convoluted by linear V3 loop antibodies. In contrast, the glycan-binding antibody 2G12 was not blocked by V3 loop mAbs (Figure S1E). Therefore, plasma blocking of 2G12 binding to Env was a more precise indicator of glycan-targeted plasma antibody responses than PGT128 or PGT125. Next, we assessed plasma 2G12 blocking over the course of immunization in M.CON-S CFI-vaccinated macaques. DNA priming and rAd5 boost resulted in minimal 2G12 blocking (Figure 1B and table S1). However, gp140CFI protein immunizations every 8 to 16 weeks increased 2G12-blocking activity, and repetitive gp140CFI boosting every 4 weeks further boosted 2G12 plasma blocking activity (mean peak 2G12 blocking ± s.e.m. = 45 ± 5%; n = 10). Thus, plasma blocking of 2G12 suggested Env-induced antibodies targeting the Man9GlcNAc2-dependent V3-glycan bnAb epitope were induced.

Figure 1. Repetitive vaccination elicits antibodies targeting the V3-glycan bnAb epitope.

(A) CON-S repetitive vaccination regimen. The immunization modality is shown below the line and the week of vaccination is noted above the line.

(B) Plasma blocking of 2G12 binding to Env. (Left) The percent blocking of 2G12 binding to B.JR-FL gp140C by macaque plasma after one DNA vaccination (week 2) or at the end of the vaccination regimen (week 204; Wilcoxon signed rank test between week 2 and 204, P<0.05 N= 10). (Right) The kinetics of 2G12 blocking antibodies in the plasma of vaccinated macaques. The mean ± SEM of triplicate measurements are shown (n= 10). Arrows on the x-axis indicate vaccination timepoints.

(C) FACS plots of sorted single B cells from week 192 PBMCs from CON-S-immunized macaque M636 that bind ConC gp120 but not N332A glycan knockout mutant gp120.

(D) Surface plasmon resonance binding to the study immunogen, CON-S gp140CFI, by DH501 and the DH501 unmutated common ancestor (UCA).

(E) Diagram of the Man9GlcNAc2 glycosylated peptide that recapitulates the PGT128 epitope. N-linked glycans (green and blue) are shown at positions Asn301 (red N) and Asn332 (red N). The disulfide bond is shown by a straight horizontal line.

(F) Direct ELISA binding to the V3 base peptide with Man9GlcNAc2 glycans at Asn301 and Asn332 (black, Man9 N332 N301 V3), at Asn301 only (red, Man9 N301 V3), or at neither site (blue, aglycone) by vaccine-induced macaque antibody DH501.

(G) Biolayer interferometry binding of DH501 and its inferred UCA to the peptides shown in E.

(H) Glycan luminex detection of antibody binding to 16 μM free glycan. The glycan-dependent bnAb PGT128 and peptide-binding antibody 19B were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The complex glycan is Gal2Man3GlcNAc4. See also Supplemental Figure 1 and 2.

Isolation of a rhesus glycan-reactive antibody that bound the V3-glycan bnAb epitope

We next isolated mAbs using antigen-specific memory B cell sorting with fluorophore-labeled consensus Env gp120 (Figure 1C). Antibody DH501 was isolated that used the rhesus IGHV2 family and had a heavy chain third complementarity determining region (CDR-H3) length of 17 amino acids (table S2). DH501 bound the vaccine immunogen CON-S gp140CFI (Figure 1D), as well as Envs from multiple clades (Figure S2). Somatic mutations were required for binding to CON-S gp140CFI since the inferred unmutated common ancestor (UCA) of DH501 did not bind CON-S gp140CFI (Figure 1D and S2). DH501 binding to M.CON-S gp140CFI was blocked 70% by 2G12 (IC50 = 20 μg/mL; Figure S2B), whereas peptide-binding V3 antibodies 447-52D and 19B did not block DH501. We determined the ability of DH501 to bind a synthetic glycopeptide with Man9GlcNAc2 glycans at N301 and N332 (Man9-V3) that mimics a portion of the gp120 V3-glycan bnAb site (Figure 1E). Both PGT128 and DH501 bound the gp120 V3-glycan minimal antigen (Figure 1F and 1G top, Alam et al., 2017). Like PGT128, DH501 did not bind the aglycone peptide lacking N301 and N332 glycans (Figure 1F and 1G top). Removal of the glycan at N332 on the glycopeptide and on Env gp120 reduced EC50 binding titers 2-fold and 4-fold for PGT128 and 2G12, respectively (Figure 1F), but did not affect DH501 (Figure 1F and 1G top). Thus, DH501 required the Man9GlcNAc2 glycan at N301 for binding to the Man9-V3 glycopeptide. A key question is what Env form bound the DH501 UCA. The DH501 UCA bound both Man9-V3 glycopeptides and aglycone peptide (Figure 1G bottom), with strongest binding to the aglycone. This binding pattern was identical to that of the UCA of a V3-glycan bnAb B cell lineage, DH270 (Alam et al., 2017; Bonsignori et al., 2017). Thus, the DH501 lineage may have been initiated by a denatured Env form or a peptide fragment (Hangartner et al., 2006; Kuraoka et al., 2016).

Similar to PGT128, DH501 bound strongly to free Man9GlcNAc2 (Figure 1H and S2C; Pejchal et al., 2011). Additionally, DH501 bound weakly to Man7GlcNAc2 D1, Man8GlcNAc2 D1D3, and Man8GlcNAc2 D1D2 (Figure 1H). Conversely, both DH501 and PGT128 did not bind directly to Gal2Man3GlcNAc4 complex glycans (Figure 1H). Therefore, terminal mannose residues on all three glycan arms conferred optimal glycan binding by DH501 and PGT128. In contrast to the mutated DH501 antibody, the DH501 UCA did not bind free glycans (Figure 1H and Figure S2C). Expression of Env in cells capable of only high mannose glycosylation (GnTI−/− cells; Crispin et al., 2006; Eggink et al., 2010; Reeves et al., 2002) improved DH501, PGT128 and 2G12 binding, but had no effect on control V3 loop peptide mAb 19B binding (Figure S2D). To express Env with high density of Man9GlcNAc2 glycans, HIV-1 B.63521 gp140CFI was expressed in the presence of kifunensine (KIF)– a glycosylation pathway inhibitor that results in Man9GlcNAc2 glycosylation (Doores and Burton, 2010; Scanlan et al., 2007b). As a positive control, the binding titer (EC50) of PGT128 to KIF-treated B.63521 Env (0.002μg/mL) was improved 40-fold compared to PGT128 binding to untreated Env (Figure S2E; Pejchal et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2011). Similar to PGT128, the EC50 of DH501 for KIF-63521 Env improved 24-fold compared to DH501 binding to untreated Env (Figure S2E). Thus, DH501 binding to Env was augmented when the glycans on Env were restricted to Man9GlcNAc2.

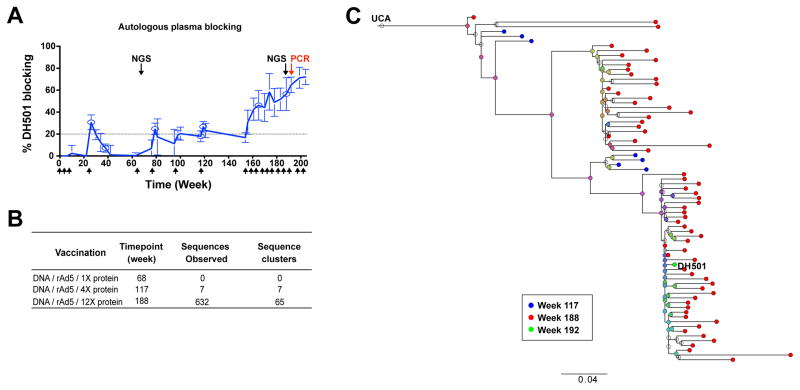

DH501 was elicited late during the vaccination regimen

We performed competition ELISAs to determine when, during vaccination of macaque M636, antibodies targeting the DH501 epitope were elicited. M636 plasma antibody blocking of DH501 binding to CON-S gp140CFI increased from weeks 156 to 204 of vaccination.

To determine the time of appearance of DH501 clonal lineage B cells, we performed next generation sequencing (NGS) of the heavy chain variable region (VH) at the beginning of the protein boosts (week 68), after 4 protein boosts (week 117), and after 12 protein boosts (week 188; Figure 2A and B). After a single protein boost there were no DH501 VH sequences detected (Figure 2B), consistent with the lack of M636 plasma blocking at the same time point (Figure 2A and B). Seven DH501 VH sequences were detected at week 117 after 4 protein boosts. In contrast, 632 sequences were isolated from duplicate sequencing experiments performed on blood B cells after 12 protein boosts at vaccination week 188 (Figure 2B). This late time point corresponded to the time of macaque M636 plasma peak blocking of mAb DH501 binding to Env (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Genetic and plasma analyses determine DH501 was elicited after multiple protein boosts.

(A) Autologous plasma blocking of DH501 binding to the CON-S immunogen. The plasma from sequential timepoints from macaque M636 from whom the DH501 glycan-reactive antibody was isolated was used to block DH501 binding to Env. Timepoints where next generation sequencing was performed in B are indicated by black arrows. The red arrow indicates where DH501 was isolated by single B cell sorting and RT-PCR. Values greater than 20% are considered positive. The mean ± SEM of triplicate measurements are shown (n= 10). Arrows on the x-axis indicate vaccination timepoints.

(B) Comparison of the number of DH501 related sequences after DNA prime, rAd5 boost, and one protein boost, four protein boosts, or 12 protein boosts in macaque M636 from which DH501 was cloned. Sequencing was performed twice at each timepoint and DH501 clonal relatedness was determined using Clonanalyst (second column). Sequences were clustered to account for sequencing error. Number of sequence clusters represents the estimated minimum number of DH501 members at each timepoint (last column).

(C) The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of the 73 total collapsed sequences (72 from NGS and DH501) that are clonally related to DH501. Time point at which the sequence was observed is indicated by the color code at the bottom. See also Supplemental Figure 3.

We clustered the DH501-related sequences to account for the effect of PCR amplification error in NGS sample preparation, and examined the genealogy of the resulting NGS sequences. The sequences segregated into two large branches with DH501 appearing in the branch that was the most genetically distant from the UCA (Figure 2C). Three sequences from week 117 and one sequence from week 188 were very similar to the inferred germline antibody of DH501 suggesting the lineage began at approximately week 117. BnAbs can be limited by immunologic tolerance (Haynes and Verkoczy, 2014); therefore we determined if DH501 was autoreactive. DH501 did not bind to host proteins or DNA antigens, nor did it bind to HIV-uninfected HEp-2 cells (Figure S3).

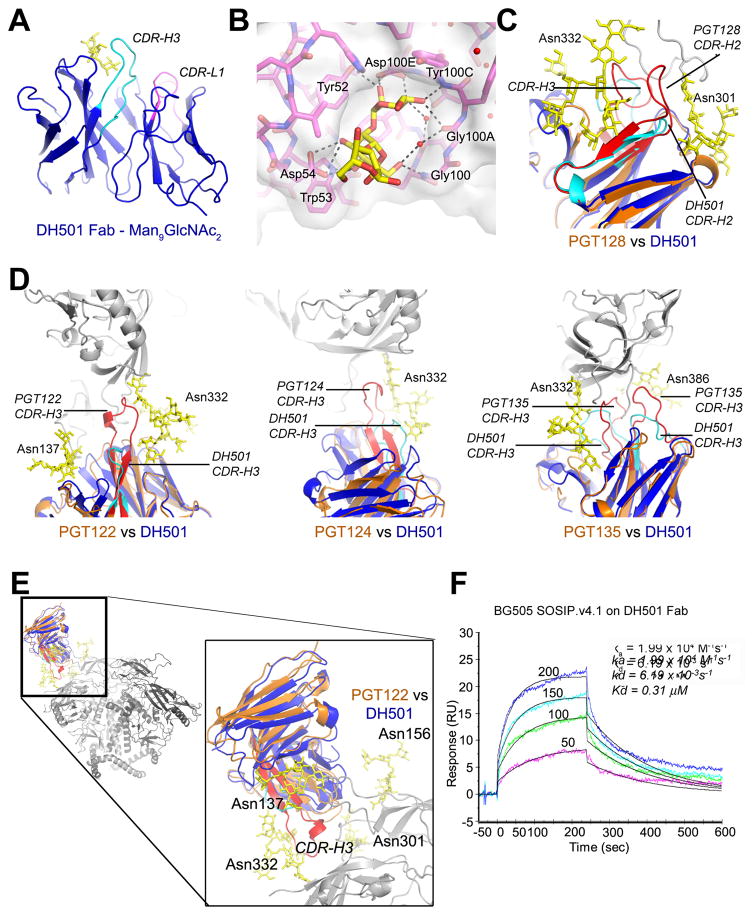

Structural analysis of glycan mAb DH501

We determined the structures of the Fab fragment of DH501 in its unliganded state to 2.8 Å resolution (PDB 5IIE) and in complex with a chemically synthesized, biotinylated Man9GlcNAc2 molecule to 2.0 Å (PDB 5T4Z; Figure 3A and table S3). The mannose residues bound in a pronounced pocket on the paratope of DH501 (Figure 3B). This pocket was formed and bounded by the three variable heavy chain CDRs. Within the VH pocket, DH501 primarily contacted the mannose residues with the side chain functional groups of Asp100E in CDR-H3 and Tyr52 in CDR-H2. Additional stabilization of the complex was established with contacts between the mannose residues and the polypeptide backbone of residues Gly100A and Tyr100C in CDR-H3 as well as through-water H bonds to the Thr100D side chain and the carbonyl of Gly100A in CDR-H3. Interestingly, the structure indicated that the most proximal mannose residue had to be a terminal one on the Man9GlcNAc2 molecule as the electron density was well defined and the structure showed no room for another mannose residue. The electron density for the most distal mannose residue was not as well defined but best corresponded with an alpha1–3 linkage, indicating the mannose residues were from the D2 arm of the synthesized Man9GlcNAc2 compound.

Figure 3. The molecular basis for high mannose and Env recognition by DH501.

(A) The structure of DH501 Fv (blue) with the paratope oriented upward. CDR-H3 is highlighted in cyan, CDR-L1 in magenta, and bound constituents of the Man9GlcNAc2 compound in yellow.

(B) Specific interactions between DH501 (magenta carbons behind a surface rendering) and bound mannose residues (yellow carbons). H-bonding interactions are shown with dashed lines and interacting residues on the DH501 heavy chain are labeled.

(C) DH501 Fv (color scheme as in A) superimposed with PGT130 Fv in orange with its CDR-H3 in red and CDR-L1 in green.

(D) DH501 Fv superimposed with the Fvs of V3-glycan broadly neutralizing antibodies in complex with gp120. Gp120 and glycan moieties are shown in gray and yellow respectively. DH501 is colored as in (A) and compared antibodies are shown in orange. Long CDRs with extended conformations in V3 glycan bnAbs are highlighted in red. N-linked Asn residues are numbered for identification of glycans.

(E) DH501 Fv (blue) superimposed on PGT122 Fv (orange) bound to the BG505.6R.SOSIP.664 trimer (grey). DH501’s CDR-H3 (cyan) lacks the length of the PGT122s CDR-H3 (red) to deeply penetrate the glycan shield (yellow).

(F) SPR binding of the DH501 Fab to a stabilized BG505 SOSIP.v4.1 trimer. Each trace represents a different concentration of Fab ranging from 50 to 200 μg/mL as indicated. The affinity measurements are displayed in the right corner of the graph. See also Supplemental Figure 4.

The DH501 Fab structure was compared to known liganded structures of gp120 V3-glycan antibodies: PGT122 (PDB 4NCO; Julien et al., 2013), PGT124 (PDB 4R2G; Garces et al., 2014), PGT128 (PDB 3TYG; (Pejchal et al., 2011), and PGT135 (PDB 4JM2; Kong et al., 2013). In direct contrast to PGT128 that had long CDR-H2 and –H3 in extended conformations, DH501 had shorter CDRs (Figure 3C). More generally, these shorter CDRs distinguished DH501 from the broadly neutralizing antibodies PGT128 and PGT135 since they all had heavy chain CDR insertions (Walker et al., 2011). Structurally, the long CDRs with extended conformations were able to penetrate the glycan shield to contact gp120 polypeptide (Figure 3D and 3E; Doores et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2013; Pejchal et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2011). When DH501 was superimposed on the structure of PGT122 binding to gp120 or the BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer, it was evident that the 26 amino acid CDR-H3 of PGT122 made contacts with the Env trimer that DH501 would be less capable of making due to its shorter 17 amino acid CDR-H3 (Figure 3E). However, despite these differences in CDR lengths and conformations, the DH501 Fab bound the near-native, closed BG505 SOSIP.v4.1 trimer (Kd = 0.31 μM; Figure 3F; de Taeye et al., 2015).

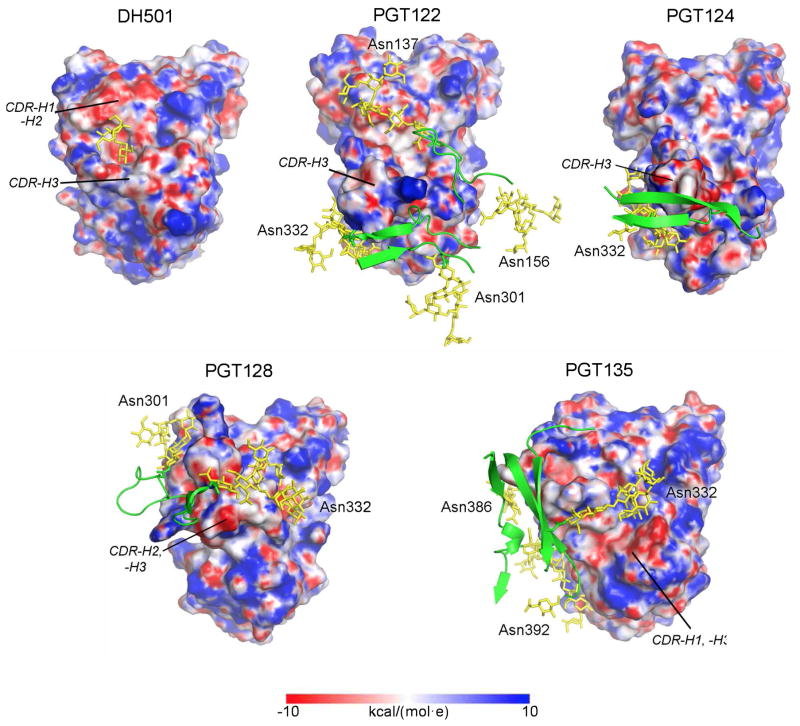

When the electrostatic surface potentials of the paratopes of DH501 and other V3 glycan antibody structures were compared, DH501 exhibited a large, negatively charged region overlapping with the glycan-binding pocket (Figure 4). The strong negative charge in the vicinity of the pocket was due to an Asp54-Asp55 doublet in CDR-H2 as well as nearby Glu57. Within the pocket itself, the negative charge was driven by the side chains of Tyr52 and Asp100E (Figure S4). This charged pocket provided a favorable environment for interacting with mannose residues in contrast to the other V3 glycan antibodies that showed broader surface features, and instead, used their long CDRs to establish more interfaces with glycoprotein.

Figure 4. DH501 accommodates high mannose glycan by forming a negatively charged glycan-binding pocket.

Paratope surfaces rendered by electrostatic surface potential along with gp120 and labeled glycans in green and yellow respectively. The electrostatic potential surface renders were calculated using CHARMM (Im et al., 1998; Jo et al., 2008a; Jo et al., 2008b) and expressed in units of kcal/(mol·e). The paratope is shown from a top view with the heavy chains oriented at the top and light chains at the bottom. CDRs with extended conformations protruding from the paratope surface are labeled in italics. V3-glycan bnAbs were characterized by one or more long CDRs and an amphipathic charge distribution. DH501 is distinguished by a pronounced pocket on its paratope bordered and formed almost entirely by the three heavy chain CDRs. The mannose residues of Man9GlcNAc2 that bind within the pocket are shown in yellow.

DH501 Neutralization of HIV-1

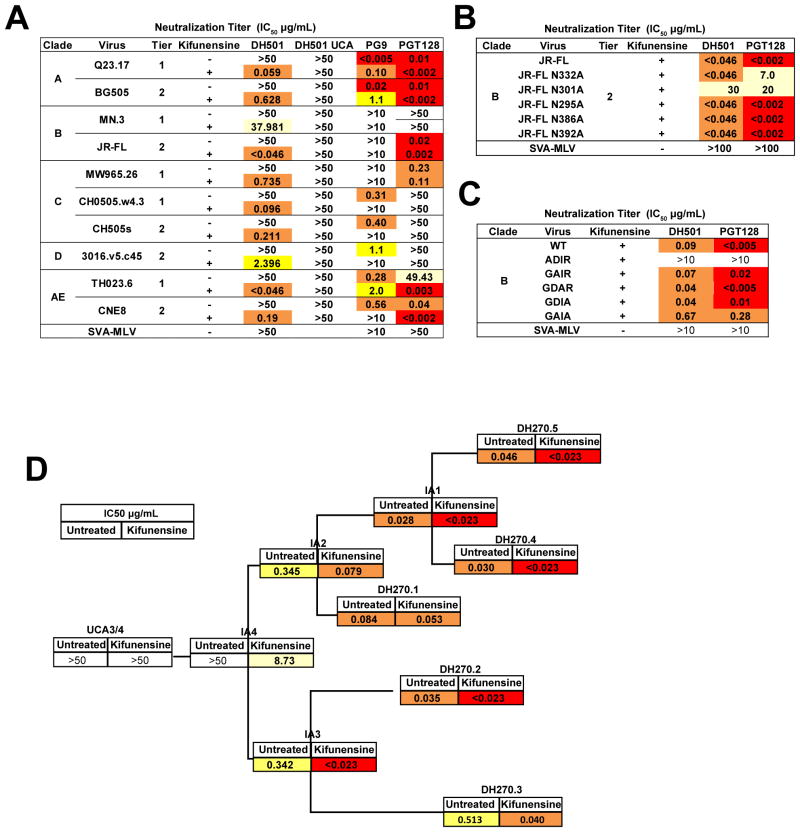

We produced B.JR-FL, A.BG505, and AE.CNE8 pseudoviruses in kifunensine (KIF) to generate pseudoviruses enriched for a high density of Man9GlcNAc2 glycosylation (KIF-JRFL, KIF-BG505, and KIF-CNE8). We found plasma IgG from 6 of 10 macaques neutralized at least 1 KIF-treated tier 2 virus, while none were able to neutralize the corresponding untreated tier 2 pseudoviruses (Figure S5A). However, the plasma did have relatively high titers of neutralizing antibodies against untreated easy-to-neutralize tier 1 pseudoviruses (Figure S5B). We produced 7 additional pseudoviruses in KIF-treated cells and tested neutralization by DH501 and its inferred UCA. The DH501 mAb neutralized 10 out of 10 KIF-treated pseudoviruses (geometric mean titer IC50 = 0.34 μg/ml), but none of the untreated pseudoviruses (Figure 5A). Neutralization activity was acquired with somatic mutation since the DH501 UCA did not neutralize any of the KIF-treated or untreated viruses (Figure 5A). As controls, KIF-treated pseudoviruses were more sensitive to PGT128 neutralization and more resistant to PG9 (V1V2 bnAb) neutralization than untreated pseudoviruses (Figure 5A; Walker et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2009). Importantly, difficult-to-neutralize (tier 2) viruses remained tier 2 in neutralization sensitivity after KIF treatment (table S4). Interestingly, KIF-B.MN was the weakest neutralized pseudovirus and lacked N301, whereas all remaining viruses in the panel had an asparagine at position 301 (Figure S5C).

Figure 5. DH501 and early V3 glycan bnAb lineage antibodies require Man9GlcNAc2 glycosylation for neutralization of HIV-1.

(A) Neutralization titers against a cross-clade panel of tier 1 and tier 2 viruses in the TZM-bl assay. Each virus was produced untreated or treated with kifunensine. PG9 (Man5GlcNAc2-reactive) and PGT128 (Man9GlcNAc2-reactive) were used as controls to demonstrate the modification of envelope glycosylation on virions. Representative titers are shown from up to 4 independent assays.

(B) DH501 exhibits N301-dependent neutralization of kifunensine-treated B.JRFL. Neutralization of kifunensine-treated B.JR-FL (KIF-JR-FL) with intact wildtype N-linked glycosylation sites or with an alanine substitution at the indicated glycosylation site. SVA is a murine leukemia virus used as a negative control for neutralization. Values are the geometric mean for two independent experiments.

(C) DH501 requires the GDIR motif for neutralization of kifunensine-treated B.JRFL. TZM-bl neutralization titers (IC50 μg/mL) for DH501 and PGT128 against wildtype and GDIR alanine mutant viruses produced in kifunensine-treated cells.

(D) Neutralization of B.JR-FL and KIF-JR-FL pseudovirus by the broadly neutralizing N332 glycan-dependent DH270 lineage antibodies. Neutralization titer is shown as IC50 (μg/mL). The IC50 for B.JR-FL neutralization is shown in the first column followed by the KIF-JR-FL neutralization titer. Neutralization titers are color coded as >50 (white), 49-1 (light yellow), 0.9–0.1 (yellow), 0.09–0.023 (orange), <0.023 (red). Titers are the geometric mean of two independent experiments. See also Supplemental Figure 5.

DH501 targets V3 glycans and the base of the V3 loop for HIV neutralization

To determine the glycans required for DH501 neutralization, we eliminated the N-linked glycosylation sites at Env amino acids 295, 301, 332, 386, or 392 in B.JR-FL by mutating asparagine to alanine at each of these positions. DH501 neutralized all KIF-JR-FL mutant viruses equivalently except the N301A mutant, for which neutralization was abrogated (Figure 5B). The N301 glycan was also necessary for neutralization of KIF-JR-FL by PGT128 (Figure 5B), consistent with its interaction with this glycan in the crystal structure of PGT128 in complex with B.JR-FL outer domain (Pejchal et al., 2011). However, DH501 neutralized KIF-JR-FL N332A whereas PGT128 showed a decrease in potency for neutralization of KIF-JR-FL N332A (Figure 5B). Thus, like Man9-V3 glycopeptide binding (Figure 1F and 1G), DH501 relied only on N301 for neutralization of KIF-JR-FL.

Most of the V3-glycan bnAbs contact the highly conserved amino acids Gly324, Asp325, Ile326, and Arg327 (GDIR motif) at the base of the V3 loop (Garces et al., 2014; Pejchal et al., 2011; Sok et al., 2016). Mutating the Gly324 (ADIR) ablated neutralization of KIF-JRFL by both DH501 and PGT128 (Figure 5C). Asp325 and Arg327 were required by PGT128 for potent neutralization of KIF-JRFL when mutated singularly (GAIR) or in tandem (GAIA). These two residues were also required by DH501 for neutralization when mutated in tandem (Figure 5C). Thus like known V3-glycan bnAbs, DH501 neutralization of KIF-treated viruses was not only N301 glycan-dependent but also relied on amino acid residues within the GDIR motif of the base of the V3 loop.

V3 glycan bnAb lineage precursors require Man9GlcNAc2 for heterologous neutralization

The significance of antibodies that neutralize kifunensine-treated viruses is a critical question. Thus, we examined the requirement for Man9GlcNAc2 glycosylation for neutralization susceptibility during the development of a V3-glycan bnAb lineage, DH270 (Figure 5D; Bonsignori et al., 2017). The DH270 bnAb lineage is N332 and N301 glycan-dependent and requires the GDIR motif for binding (Bonsignori et al., 2017). The DH270 UCA did not neutralize either untreated B.JR-FL or KIF-JR-FL (Figure 5D). Similar to DH501, the first DH270 B cell lineage intermediate antibody IA4 neutralized KIF-JR-FL (IC50 = 8.73 μg/mL), but not the untreated B.JR-FL pseudovirus. Intermediate antibodies IA2 and IA3 neutralized KIF-JR-FL 5-fold and 10-fold more potently compared to untreated B.JR-FL respectively. B.JR-FL neutralization by more mutated DH270 bnAb lineage antibodies were less affected by kifunensine treatment (Figure 5D). Thus, like DH501, precursors in the V3-glycan bnAb lineage required high density of Man9GlcNAc2 for HIV-1 B.JR-FL neutralization, while affinity-matured V3-glycan bnAbs acquired the ability to neutralize B.JR-FL regardless of virus high mannose glycan enrichment.

Discussion

Here we have demonstrated that Man9GlcNAc2-dependent Env antibodies can be induced in the setting of vaccination with Envs glycosylated with V3 Man9GlcNAc2 glycans. Several groups have attempted to elicit 2G12-like antibodies using BSA-conjugated to high mannose (Astronomo et al., 2008) phage bearing high mannose (Astronomo et al., 2010; Doores et al., 2010b), or synthetic glycopeptides (Joyce et al., 2008). However, these studies were unable to produce 2G12-like antibodies, perhaps due to the domain-swap within 2G12 (Calarese et al., 2003), lack of immunogenicity of host glycans (Scanlan et al., 2007b), or the lack of high mannose glycosylation on recombinant 293 cell line-produced gp120 and cleavage-deficient non-SOSIP gp140 immunogens (Bonomelli et al., 2011; Doores et al., 2010a; Go et al., 2008). In a recent study, one out of 15 rabbits immunized with an Env trimer had a reduction in neutralization potency when the N332 glycan site was deleted on HIV-1 Env (Sanders et al., 2015). The rarity of V3-glycan-dependent antibodies elicited by vaccination has raised the question of whether or not Env high mannose glycans are immunogenic (Scanlan et al., 2007a). Mannose is a component of the cell wall of fungal pathogens to which the human immune system has evolved to make antibodies (Deshaw and Pirofski, 1995); however, the recognition of the precise arrangement of mannose and the accommodation or avoidance of complex glycans on Env may be the obstacle for eliciting HIV-1 Env glycan antibodies (Garces et al., 2015). Anti-fungal antibodies have been induced in rabbits that neutralize HIV-1 produced in kifunensine (Agrawal-Gamse et al., 2011; Dunlop et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2015), but whether these antibodies target bnAb epitopes such as the N332 glycan or require the GDIR motif is unknown. Furthermore, our study shows that the significance of kifunensine-dependent neutralization is that when V3 glycan bnAb lineages are initiated in HIV-1 infection, bnAb precursors require Man9GlcNAc2 Env glycosylation for heterologous neutralization, and evolve with affinity maturation to be less dependent on a high density of Man9GlcNAc2. Structural studies of the PGT121 family have shown that as antibodies evolve they acquire binding mechanisms to avoid or accommodate interfering glycans (Garces et al., 2015). While the ability to neutralize KIF-treated HIV is a trait of early V3-glycan bnAb precursors, it should be emphasized that not all antibodies like DH501 that neutralize KIF-treated HIV may have the capacity to affinity mature to full bnAb breadth. Thus, the only way to definitively know if DH501 is on the path to become a bnAb is to isolate a DH501-like affinity matured bnAb, and work is underway to seek such antibodies.

The mode of glycan recognition by DH501 is distinct from bnAbs like PGT121 or PGT128, which use long loops in extended conformations to contact glycans (Figure 3). The lack of these long, extended loops and instead the presence of a glycan-binding pocket is compatible with a scenario in which the glycan inserts into the cavity, allowing DH501 to move proximal to the peptide backbone and thereby contact the GDIR motif.

How to increase the neutralization breadth of vaccine-induced antibodies like DH501 is a key question. Superpositions of DH501 with V3-glycan bnAbs demonstrated that DH501 lacked the protruding CDR loops created by insertions (Figure 3C, 3D, and S4). Insertions and deletions are common in V3-glycan bnAbs (Walker et al., 2011), but are events rarely found in the antibody repertoire (Kepler et al., 2014), and may represent a roadblock to bnAb induction. The removal of the insertion in the CDR-H2 of PGT128 diminished its neutralization potency and N332 glycan dependence (Doores et al., 2014; Pejchal et al., 2011) supporting the notion that insertion and deletions may be required for optimal neutralization breadth. Future studies will aim to induce AID-mediated insertions and deletions by vaccinating under conditions that promote AID activity (Bowers et al., 2014). Also 2G12 did not block 100% of DH501 binding to Env, which could be due to DH501 requiring the N301 glycan more than the N332 glycan. The N332 glycan is one of the most abundantly targeted sites on Env for broadly neutralizing antibodies in sera (Walker et al., 2010). Whether the N301 glycan recognition alone is sufficient to confer broad neutralization is unknown.

To select V3-glycan antibodies that mature during vaccination into broadly neutralizing antibodies will likely require a sequential Env vaccination regimen (Bonsignori et al., 2017; Bonsignori et al., 2016; Escolano et al., 2016; Haynes et al., 2012; Liao et al., 2013a). Synthetic peptides from the base of the V3 loop that bound to the DH501 UCA (Figure 1G) and the DH270 UCA could prove useful as germline-targeting immunogens to initiate V3-glycan bnAb antibodies. This peptide, although it contains a disulfide bond to link the N and C terminus providing a conformation similar to the base of the V3 loop, and binds to the UCA, may not be optimal for induction of conformational Env antibodies, unless the disulfide-bonded loop is sufficient for this purpose. The peptide does not contain the tip of the V3 loop that is immunogenic for non-neutralizing antibodies, but instead include the base of the V3 loop that contains the GDIR motif that is bound by many V3-glycan bnAbs (Garces et al., 2015; Garces et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2013). Priming immunizations with the V3 base peptide may be more beneficial than priming with a gp140, since the UCA of the V3-glycan bnAb DH270 did not bind to the N332 and N301 glycan-deleted gp140, but did bind to the aglycone V3 base peptide (Bonsignori et al., 2017). This difference in binding could be due to the V1V2 loop and its glycans shielding the base of the V3 loop in the context of gp140 (Bonsignori et al., 2017; Steichen et al., 2016). It will be of interest to study this peptide in DH270 UCA VH and VL bnAb knock-in mice to determine the usefulness of the peptide as an immunogen. Subsequent boosts could include repetitive vaccination with sequential Envs from HIV-1 infected individuals who develop V3-glycan bnAbs that have been expressed with only Man9GlcNAc2 since we show here the earliest bnAb lineage members require Man9GlcNAc2 for recognition of trimer (Bonsignori et al., 2017; Escolano et al., 2016; MacLeod et al., 2016). Additionally, many bnAbs are limited by immunologic tolerance (Haynes and Verkoczy, 2014), therefore relaxing tolerance while vaccinating may also be necessary for bnAb induction. Relaxation of tolerance controls coupled with the types of regimens described above could shorten the time needed to elicit V3-glycan antibodies compared to the study described here. However, immunization occurs yearly with influenza and thus may also be possible for HIV-1 vaccines. Vaccination of infants and continued boosts throughout life may also be a plausible method for repetitively vaccinating against HIV-1 in high-risk populations. Nonetheless, the results presented here demonstrate that induction of antibodies targeting the V3-glycan bnAb epitope with an Env expressing Man9GlcNAc2 glycans at the base of the V3 loop is possible with repetitive immunizations, and represent a first step in the induction of V3-glycan-targeted neutralizing antibody B cell lineages in primates.

Experimental Procedures

Experimental design

Indian origin rhesus macaques (N=10) were administered CON-S gp145 or gp140CFI as described in Figure 1A and Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Indian origin rhesus macaques were housed in an AALAC-accredited facility, and all procedures were conducted with IACUC approval.

Oligomannose bead immunoassay

Antibody binding to free glycan was measured by a custom glycan luminex microsphere assay as detailed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) detection of antibody binding to gp140

Binding of CON-S gp140CFI (100mg/mL) or BG505 SOSIP.664.v4.1 gp140 (228nM to 913nM) was measured by SPR (BIAcoreS200, GE Healthcare) analysis following capture of each mAbs on anti-human Ig Fc immobilized or direct immobilization of Fabs on sensors as described earlier (Alam et al., 2013).

Man9GlcNAc2-V3 glycopeptide and aglycone bio-layer Interferometry (BLI)

Antibody binding to biotinylated synthetic glycopeptide was measured by Bio-layer Interferometry (BLI, ForteBio Octet Red96) analysis.

Direct ELISAs

ELISA plates were coated with antigen, blocked, and incubated with serially diluted antibodies. Biotinylated antigens were captured with streptavidin. Bound antibody was detected with anti-human IgG (Rockland) or an anti-rhesus IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). HRP was detected with TMB (KPL) and read with a SpectraMax plate reader (Molecular Devices) and SoftMax Pro v5.3 (Molecular Devices). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Plasma and antibody blocking of N332 glycan-dependent bnAb

B.JRFL gp140C coated plates were incubated sequentially with blocking plasma or blocking antibody followed by addition of biotinylated antibodies of interest. Binding in the presence of competitor was compared to binding in the absence of the competitor antibodies to determine percent blocking. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Epitope-specific single B cell sorting

B cell sorting was performed as described previously (Wiehe et al., 2014) with fluorophore-labeled ConC gp120 and ConC N332A gp120 as stated in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Rhesus Immunoglobulin RT-PCR

Immunoglobulin genes were amplified as previously described (Liao et al., 2009; Wiehe et al., 2014). Contigs of the PCR amplicon sequence were made and gene were inferred with the human library in SoDA and the rhesus library in Clonanalyst (Volpe et al., 2006; Wiehe et al., 2014). Unmutated common ancestor antibodies were inferred using the rhesus library in Clonanalyst. Antibodies were expressed as described in (Zhang et al., 2016).

Next generation sequencing of antibody genes

Illumina MiSeq sequencing of antibody heavy chain VDJ sequences was performed on peripheral B cells as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016). For each timepoint sequencing was performed twice on independent cDNA samples to confirm the absence or presence of antibody sequences of interest. From single template NGS experiments, we have observed that the number of errors introduced in PCR amplification in our NGS sample preparation rarely exceeds four base pairs (<1%). Thus two sequences that each differ by 4 base pairs (8 total base pair differences) cannot be reliably determined to derive from two unique B cells. To conservatively account for this, we clustered together sequences with 8 or fewer base pair differences. V, D, and J gene segment inference, clonal relatedness testing and reconstruction of clonal lineage trees were performed using the Cloanalyst software package (Kepler, 2013).

HEp-2 cells immunofluorescence

Rhesus antibodies were tested at 25 and 50 μg/mL in the HEp-2 cell immunofluorescence assay (Inverness Medical Professional Diagnostics) as described previously (Moody et al., 2012).

Recombinant Env expression

Recombinant Env was produced in 293F cells by transient transfection as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. BG505 SOSIP.v4.1 trimers were purified using PGT145-affinity chromatography as previously described (de Taeye et al., 2015).

Glycosylation analysis

Glycan analysis was performed by LC-MS/MS as previously described (Go et al., 2015; Go et al., 2013). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

In vitro HIV-1 neutralization

Neutralizing antibody activity was measured in 96-well culture plates by using Tat-regulated luciferase (Luc) reporter gene expression to quantify reductions in virus infection in TZM-bl cells.

Crystallography

Crystallization conditions were tested in a variety of commercially available screens (Qiagen, Hampton Research) and crystals of the unliganded Fab were observed over a reservoir of 0.1 M HEPES pH 6.5, 20% PEG 6,000 at a temperature of 20 °C. Purified DH501 Fab was also mixed with Man9GlcNAc2-biotin in a 1:3 molar ratio then treated to the same procedure as the unliganded Fab. Crystals were observed over a reservoir of 0.2 M CaCl2, 20% PEG 3350. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 5IIE (unliganded Fab) and 5T4Z (liganded Fab). Structural figures were generated with Pymol (Delano). Further details are in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Statistical analysis plan

Descriptive statistics were used to describe immune responses. Neutralization data was averaged across experiments as geometric means. A Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was performed including all ten animals to compare differences in plasma blocking at two different timepoints. Statistics were calculated with SAS v9.4.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Env vaccination elicits antibodies that target the V3-glycan neutralizing epitope

Repetitive vaccination with a single Env over 4 years induced V3-glycan antibodies

V3-glycan bnAb precursors recognize Env Man9GlcNAc2 in order to neutralize

Acknowledgments

We thank Lawrence Armand, Andrew Foulger, Christina Stolarchuck, and Krissey Lloyd for technical assistance. We also thank the Duke Human Vaccine Institute Flow Cytometry Core. We thank Nathan Vandergrift and R. Wes Roundtree for statistical analyses. Crystallography was performed in the Duke University X-ray Crystallography Shared Resource. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. We are grateful for NIH, NIAID, Division of AIDS Simian Vaccine Evaluation Unit program support under the Advanced BioScience Laboratories SVEU contract number N01-AI-60005. We are grateful for insightful discussions with Dr. Nancy Miller. This work was supported by NIAID extramural project grant R01-AI120801 (K.O.S.), Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) training grant T32GM007171, Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F30-AI122982-0, NIAID (R.R.M), T32 AIDS Training Grant AI007392, and NIH, NIAID, Division of AIDS UM1 grant AI100645 for the Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology-Immunogen Discovery (CHAVI-ID). B.K., B.F.H. and H.X.L. have filed International Patent Application PCT/US2004/030397 and National Stage Applications directed to CON-S and use as an immunogen.

Footnotes

Accession Numbers

The coordinates and structure factors for the DH501 unliganded Fab and the Fab-Man9GlcNAc2 complex are deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 5IIE and 5T4Z, respectively. The sequence of DH501 heavy and light chain is deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KY490540 and KY490541 respectively. The sequence of DH501 unmutated common ancestor heavy and light chain is deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KY490542 and KY490543 respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization KOS, BFH: Investigation KOS, NIN, NRW, AF, MB, RRM, KA, EG, WEW, BA, YV, PKP, RWS, FPC, RZ, TVH, RP, RGO, AE, DB, SS, LLS, RS, BTK; Writing KOS and BFH; Supervision BFH, KOS, MB, GDT, SMA, SJD; MAM, DCM, HXL, GJN, NLL; Funding Acquisition KOS and BFH; Formal analysis KOS, NIN, KW, EG, HD RGO, TBK, BFH; Software TBK.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agrawal-Gamse C, Luallen RJ, Liu B, Fu H, Lee FH, Geng Y, Doms RW. Yeast-elicited cross-reactive antibodies to HIV Env glycans efficiently neutralize virions expressing exclusively high-mannose N-linked glycans. J Virol. 2011;85:470–480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01349-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SM, Aussedat B, Vohra Y, Meyerhoff RR, Cale EM, Walkowicz WE, Radakovich NA, Anasti K, Armand L, Parks R, et al. Mimicry of an HIV Broadly Neutralizing Antibody Epitope with a Synthetic Glycopeptide. Sci Transl Med. 2017 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai7521. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astronomo RD, Kaltgrad E, Udit AK, Wang SK, Doores KJ, Huang CY, Pantophlet R, Paulson JC, Wong CH, Finn MG, Burton DR. Defining criteria for oligomannose immunogens for HIV using icosahedral virus capsid scaffolds. Chem Biol. 2010;17:357–370. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astronomo RD, Lee HK, Scanlan CN, Pantophlet R, Huang CY, Wilson IA, Blixt O, Dwek RA, Wong CH, Burton DR. A glycoconjugate antigen based on the recognition motif of a broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus antibody, 2G12, is immunogenic but elicits antibodies unable to bind to the self glycans of gp120. J Virol. 2008;82:6359–6368. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00293-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner C, Lee JH, Sliepen K, Derking R, Falkowska E, de la Pena AT, Cupo A, Julien JP, van Gils M, Lee PS, et al. Structural delineation of a quaternary, cleavage-dependent epitope at the gp41-gp120 interface on intact HIV-1 Env trimers. Immunity. 2014;40:669–680. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomelli C, Doores KJ, Dunlop DC, Thaney V, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Crispin M, Scanlan CN. The glycan shield of HIV is predominantly oligomannose independently of production system or viral clade. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsignori M, Kreider EF, Fera D, Meyerhoff RR, Bradley T, Wiehe K, Alam SM, Aussedat B, Walkowicz WE, Hwang KK, et al. Staged induction of HIV-1 glycan-dependent broadly neutralizing antibodies. Sci Transl Med. 2017 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai7514. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsignori M, Zhou T, Sheng Z, Chen L, Gao F, Joyce MG, Ozorowski G, Chuang GY, Schramm CA, Wiehe K, et al. Maturation Pathway from Germline to Broad HIV-1 Neutralizer of a CD4-Mimic Antibody. Cell. 2016;165:449–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers PM, Verdino P, Wang Z, da Silva Correia J, Chhoa M, Macondray G, Do M, Neben TY, Horlick RA, Stanfield RL, et al. Nucleotide insertions and deletions complement point mutations to massively expand the diversity created by somatic hypermutation of antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:33557–33567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.607176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley T, Fera D, Bhiman J, Eslamizar L, Lu X, Anasti K, Zhang R, Sutherland LL, Scearce RM, Bowman CM, et al. Structural Constraints of Vaccine-Induced Tier-2 Autologous HIV Neutralizing Antibodies Targeting the Receptor-Binding Site. Cell Rep. 2016;14:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton DR, Ahmed R, Barouch DH, Butera ST, Crotty S, Godzik A, Kaufmann DE, McElrath MJ, Nussenzweig MC, Pulendran B, et al. A Blueprint for HIV Vaccine Discovery. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarese DA, Scanlan CN, Zwick MB, Deechongkit S, Mimura Y, Kunert R, Zhu P, Wormald MR, Stanfield RL, Roux KH, et al. Antibody domain exchange is an immunological solution to carbohydrate cluster recognition. Science. 2003;300:2065–2071. doi: 10.1126/science.1083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti D, Lanzavecchia A. Broadly neutralizing antiviral antibodies. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:705–742. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Chang VT, Yu C, Aricescu AR, Jones EY, Davis SJ, Dwek RA, Rudd PM. Inhibition of hybrid- and complex-type glycosylation reveals the presence of the GlcNAc transferase I-independent fucosylation pathway. Glycobiology. 2006;16:748–756. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks ET, Tong T, Chakrabarti B, Narayan K, Georgiev IS, Menis S, Huang X, Kulp D, Osawa K, Muranaka J, et al. Vaccine-Elicited Tier 2 HIV-1 Neutralizing Antibodies Bind to Quaternary Epitopes Involving Glycan-Deficient Patches Proximal to the CD4 Binding Site. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004932. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Taeye SW, Ozorowski G, Torrents de la Pena A, Guttman M, Julien JP, van den Kerkhof TL, Burger JA, Pritchard LK, Pugach P, Yasmeen A, et al. Immunogenicity of Stabilized HIV-1 Envelope Trimers with Reduced Exposure of Non-neutralizing Epitopes. Cell. 2015;163:1702–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Schrödinger LLC; [Google Scholar]

- Deshaw M, Pirofski LA. Antibodies to the Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan are ubiquitous in serum from HIV+ and HIV− individuals. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb05568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doores KJ. The HIV glycan shield as a target for broadly neutralizing antibodies. FEBS J. 2015;282:4679–4691. doi: 10.1111/febs.13530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doores KJ, Bonomelli C, Harvey DJ, Vasiljevic S, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Crispin M, Scanlan CN. Envelope glycans of immunodeficiency virions are almost entirely oligomannose antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010a;107:13800–13805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006498107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doores KJ, Burton DR. Variable loop glycan dependency of the broad and potent HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies PG9 and PG16. J Virol. 2010;84:10510–10521. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00552-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doores KJ, Fulton Z, Hong V, Patel MK, Scanlan CN, Wormald MR, Finn MG, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Davis BG. A nonself sugar mimic of the HIV glycan shield shows enhanced antigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010b;107:17107–17112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002717107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doores KJ, Kong L, Krumm SA, Le KM, Sok D, Laserson U, Garces F, Poignard P, Wilson IA, Burton DR. Two classes of broadly neutralizing antibodies within a single lineage directed to the high-mannose patch of HIV Envelope. J Virol. 2014;89:1105–1118. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02905-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doria-Rose NA, Klein RM, Manion MM, O’Dell S, Phogat A, Chakrabarti B, Hallahan CW, Migueles SA, Wrammert J, Ahmed R, et al. Frequency and phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus envelope-specific B cells from patients with broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2009;83:188–199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01583-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doria-Rose NA, Schramm CA, Gorman J, Moore PL, Bhiman JN, DeKosky BJ, Ernandes MJ, Georgiev IS, Kim HJ, Pancera M, et al. Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2014;509:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop DC, Bonomelli C, Mansab F, Vasiljevic S, Doores KJ, Wormald MR, Palma AS, Feizi T, Harvey DJ, Dwek RA, et al. Polysaccharide mimicry of the epitope of the broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibody, 2G12, induces enhanced antibody responses to self oligomannose glycans. Glycobiology. 2010;20:812–823. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggink D, Melchers M, Wuhrer M, van Montfort T, Dey AK, Naaijkens BA, David KB, Le Douce V, Deelder AM, Kang K, et al. Lack of complex N-glycans on HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins preserves protein conformation and entry function. Virology. 2010;401:236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escolano A, Steichen JM, Dosenovic P, Kulp DW, Golijanin J, Sok D, Freund NT, Gitlin AD, Oliveira T, Araki T, et al. Sequential immunization elicits broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies in Ig knockin mice. Cell. 2016;166:1445–14458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci AS, Marston HD. Ending AIDS--is an HIV vaccine necessary? N Engl J Med. 2014;370:495–498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1313771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garces F, Lee JH, de Val N, Torrents de la Pena A, Kong L, Puchades C, Hua Y, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Moore JP, et al. Affinity Maturation of a Potent Family of HIV Antibodies Is Primarily Focused on Accommodating or Avoiding Glycans. Immunity. 2015;43:1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garces F, Sok D, Kong L, McBride R, Kim HJ, Saye-Francisco KF, Julien JP, Hua Y, Cupo A, Moore JP, et al. Structural evolution of glycan recognition by a family of potent HIV antibodies. Cell. 2014;159:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go EP, Herschhorn A, Gu C, Castillo-Menendez L, Zhang S, Mao Y, Chen H, Ding H, Wakefield JK, Hua D, et al. Comparative Analysis of the Glycosylation Profiles of Membrane-Anchored HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein Trimers and Soluble gp140. J Virol. 2015;89:8245–8257. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00628-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go EP, Irungu J, Zhang Y, Dalpathado DS, Liao HX, Sutherland LL, Alam SM, Haynes BF, Desaire H. Glycosylation site-specific analysis of HIV envelope proteins (JR-FL and CON-S) reveals major differences in glycosylation site occupancy, glycoform profiles, and antigenic epitopes’ accessibility. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1660–1674. doi: 10.1021/pr7006957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go EP, Liao HX, Alam SM, Hua D, Haynes BF, Desaire H. Characterization of host-cell line specific glycosylation profiles of early transmitted/founder HIV-1 gp120 envelope proteins. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:1223–1234. doi: 10.1021/pr300870t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ES, Madiga MC, Hermanus T, Moore PL, Wibmer CK, Tumba NL, Werner L, Mlisana K, Sibeko S, Williamson C, et al. The neutralization breadth of HIV-1 develops incrementally over four years and is associated with CD4+ T cell decline and high viral load during acute infection. J Virol. 2011;85:4828–4840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00198-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangartner L, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Antiviral antibody responses: the two extremes of a wide spectrum. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:231–243. doi: 10.1038/nri1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes BF, Kelsoe G, Harrison SC, Kepler TB. B-cell-lineage immunogen design in vaccine development with HIV-1 as a case study. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:423–433. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes BF, Verkoczy L. AIDS/HIV. Host controls of HIV neutralizing antibodies. Science. 2014;344:588–589. doi: 10.1126/science.1254990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im W, Beglov D, Roux B. Continuum solvation model: computation of electrostatic forces from numerical solutions to the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. Comput Phys Comm. 1998;111:59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J Comput Chem. 2008a;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Vargyas M, Vasko-Szedlar J, Roux B, Im W. PBEQ-Solver for online visualization of electrostatic potential of biomolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008b;36:W270–275. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JG, Krauss IJ, Song HC, Opalka DW, Grimm KM, Nahas DD, Esser MT, Hrin R, Feng M, Dudkin VY, et al. An oligosaccharide-based HIV-1 2G12 mimotope vaccine induces carbohydrate-specific antibodies that fail to neutralize HIV-1 virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15684–15689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807837105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, et al. Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1477–1483. doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler TB. Reconstructing a B-cell clonal lineage. I. Statistical inference of unobserved ancestors. F1000Res. 2013;2:103. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-103.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler TB, Liao HX, Alam SM, Bhaskarabhatla R, Zhang R, Yandava C, Stewart S, Anasti K, Kelsoe G, Parks R, et al. Immunoglobulin gene insertions and deletions in the affinity maturation of HIV-1 broadly reactive neutralizing antibodies. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Lee JH, Doores KJ, Murin CD, Julien JP, McBride R, Liu Y, Marozsan A, Cupo A, Klasse PJ, et al. Supersite of immune vulnerability on the glycosylated face of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraoka M, Schmidt AG, Nojima T, Feng F, Watanabe A, Kitamura D, Harrison SC, Kepler TB, Kelsoe G. Complex Antigens Drive Permissive Clonal Selection in Germinal Centers. Immunity. 2016;44:542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CK, Spellman MW, Riddle L, Harris RJ, Thomas JN, Gregory TJ. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10373–10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HX, Levesque MC, Nagel A, Dixon A, Zhang R, Walter E, Parks R, Whitesides J, Marshall DJ, Hwang KK, et al. High-throughput isolation of immunoglobulin genes from single human B cells and expression as monoclonal antibodies. J Virol Methods. 2009;158:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HX, Lynch R, Zhou T, Gao F, Alam SM, Boyd SD, Fire AZ, Roskin KM, Schramm CA, Zhang Z, et al. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature. 2013a;496:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HX, Tsao CY, Alam SM, Muldoon M, Vandergrift N, Ma BJ, Lu X, Sutherland LL, Scearce RM, Bowman C, et al. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of transmitted/founder, consensus, and chronic envelope glycoproteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2013b;87:4185–4201. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02297-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod DT, Choi NM, Briney B, Garces F, Ver LS, Landais E, Murrell B, Wrin T, Kilembe W, Liang CH, et al. Early Antibody Lineage Diversification and Independent Limb Maturation Lead to Broad HIV-1 Neutralization Targeting the Env High-Mannose Patch. Immunity. 2016;44:1215–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascola JR, Haynes BF. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies: understanding nature’s pathways. Immunol Rev. 2013;254:225–244. doi: 10.1111/imr.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascola JR, Montefiori DC. The role of antibodies in HIV vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy LE, van Gils MJ, Ozorowski G, Messmer T, Briney B, Voss JE, Kulp DW, Macauley MS, Sok D, Pauthner M, et al. Holes in the Glycan Shield of the Native HIV Envelope Are a Target of Trimer-Elicited Neutralizing Antibodies. Cell Rep. 2016;16:2327–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan JS, Pancera M, Carrico C, Gorman J, Julien JP, Khayat R, Louder R, Pejchal R, Sastry M, Dai K, et al. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature. 2011;480:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldt B, Rakasz EG, Schultz N, Chan-Hui PY, Swiderek K, Weisgrau KL, Piaskowski SM, Bergman Z, Watkins DI, Poignard P, Burton DR. Highly potent HIV-specific antibody neutralization in vitro translates into effective protection against mucosal SHIV challenge in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18921–18925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214785109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody MA, Yates NL, Amos JD, Drinker MS, Eudailey JA, Gurley TC, Marshall DJ, Whitesides JF, Chen X, Foulger A, et al. HIV-1 gp120 vaccine induces affinity maturation in both new and persistent antibody clonal lineages. J Virol. 2012;86:7496–7507. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00426-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murin CD, Julien JP, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Khayat R, Cupo A, Moore JP, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Ward AB. Structure of 2G12 Fab2 in complex with soluble and fully glycosylated HIV-1 Env by negative-stain single-particle electron microscopy. J Virol. 2014;88:10177–10188. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01229-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancera M, Zhou T, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Soto C, Gorman J, Huang J, Acharya P, Chuang GY, Ofek G, et al. Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre-fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature. 2014;514:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parren PW, Burton DR. The antiviral activity of antibodies in vitro and in vivo. Adv Immunol. 2001;77:195–262. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(01)77018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pejchal R, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS, Wang SK, Stanfield RL, Julien JP, Ramos A, Crispin M, et al. A potent and broad neutralizing antibody recognizes and penetrates the HIV glycan shield. Science. 2011;334:1097–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.1213256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: high-level expression of rhodopsin with restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation by a tetracycline-inducible N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative HEK293S stable mammalian cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders RW, van Gils MJ, Derking R, Sok D, Ketas TJ, Burger JA, Ozorowski G, Cupo A, Simonich C, Goo L, et al. HIV-1 VACCINES. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies induced by native-like envelope trimers. Science. 2015;349:aac4223. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather DN, Armann J, Ching LK, Mavrantoni A, Sellhorn G, Caldwell Z, Yu X, Wood B, Self S, Kalams S, Stamatatos L. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2009;83:757–769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan CN, Offer J, Zitzmann N, Dwek RA. Exploiting the defensive sugars of HIV-1 for drug and vaccine design. Nature. 2007a;446:1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature05818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan CN, Ritchie GE, Baruah K, Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Singer BB, Lucka L, Wormald MR, Wentworth P, Jr, Zitzmann N, et al. Inhibition of mammalian glycan biosynthesis produces non-self antigens for a broadly neutralising, HIV-1 specific antibody. J Mol Biol. 2007b;372:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simek MD, Rida W, Priddy FH, Pung P, Carrow E, Laufer DS, Lehrman JK, Boaz M, Tarragona-Fiol T, Miiro G, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite neutralizers: individuals with broad and potent neutralizing activity identified by using a high-throughput neutralization assay together with an analytical selection algorithm. J Virol. 2009;83:7337–7348. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonich CA, Williams KL, Verkerke HP, Williams JA, Nduati R, Lee KK, Overbaugh J. HIV-1 Neutralizing Antibodies with Limited Hypermutation from an Infant. Cell. 2016;166:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sok D, Pauthner M, Briney B, Lee JH, Saye-Francisco KL, Hsueh J, Ramos A, Le KM, Jones M, Jardine JG, et al. A Prominent Site of Antibody Vulnerability on HIV Envelope Incorporates a Motif Associated with CCR5 Binding and Its Camouflaging Glycans. Immunity. 2016;45:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steichen JM, Kulp DW, Tokatlian T, Escolano A, Dosenovic P, Stanfield RL, McCoy LE, Ozorowski G, Hu X, Kalyuzhniy O, et al. HIV Vaccine Design to Target Germline Precursors of Glycan-Dependent Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Immunity. 2016;45:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M, Cheng C, Chen X, Duan H, Cheng HL, Dao M, Sheng Z, Kimble M, Wang L, Lin S, et al. Induction of HIV Neutralizing Antibody Lineages in Mice with Diverse Precursor Repertoires. Cell. 2016;166:1471–1484. e1418. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe JM, Cowell LG, Kepler TB. SoDA: implementation of a 3D alignment algorithm for inference of antigen receptor recombinations. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:438–444. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btk004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien JP, Wang SK, Ramos A, Chan-Hui PY, Moyle M, et al. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature. 2011;477:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, et al. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science. 2009;326:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LM, Simek MD, Priddy F, Gach JS, Wagner D, Zwick MB, Phogat SK, Poignard P, Burton DR. A limited number of antibody specificities mediate broad and potent serum neutralization in selected HIV-1 infected individuals. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001028. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SK, Liang PH, Astronomo RD, Hsu TL, Hsieh SL, Burton DR, Wong CH. Targeting the carbohydrates on HIV-1: Interaction of oligomannose dendrons with human monoclonal antibody 2G12 and DC-SIGN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3690–3695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712326105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, et al. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiehe K, Easterhoff D, Luo K, Nicely NI, Bradley T, Jaeger FH, Dennison SM, Zhang R, Lloyd KE, Stolarchuk C, et al. Antibody Light-Chain-Restricted Recognition of the Site of Immune Pressure in the RV144 HIV-1 Vaccine Trial Is Phylogenetically Conserved. Immunity. 2014;41:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Fu H, Luallen RJ, Liu B, Lee FH, Doms RW, Geng Y. Antibodies elicited by yeast glycoproteins recognize HIV-1 virions and potently neutralize virions with high mannose N-glycans. Vaccine. 2015;33:5140–5147. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Verkoczy L, Wiehe K, Munir Alam S, Nicely NI, Santra S, Bradley T, Pemble CW, IV, Zhang J, Gao F, et al. Initiation of immune tolerance-controlled HIV gp41 neutralizing B cell lineages. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:336ra362. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf0618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Zhu J, Wu X, Moquin S, Zhang B, Acharya P, Georgiev IS, Altae-Tran HR, Chuang GY, Joyce MG, et al. Multidonor analysis reveals structural elements, genetic determinants, and maturation pathway for HIV-1 neutralization by VRC01-class antibodies. Immunity. 2013;39:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.