Abstract

Introduction:

In the last few years, viscoelastic point-of-care (POC) coagulation devices such as thromboelastography (TEG), rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM), and Sonoclot (SON) analyzer have been increasingly used in major surgeries for timely assessment and management of coagulopathies. The aim of the present study was to evaluate coagulation profile of cyanotic cardiac patients with TEG, ROTEM, and SON analyzer. In addition, we assessed the correlation of standard laboratory coagulation tests and postoperative chest drain output (CDO) with the parameters of POC testing devices.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty-five patients of either gender, belonging to the American Society of Anesthesiologists Grade I–III, and undergoing elective cardiac surgery on cardiopulmonary bypass for cyanotic congenital heart disease were included in this study. To identify possible coagulation abnormalities, blood samples for TEG, ROTEM, SON, and standard laboratory coagulation were collected after induction of anesthesia. The correlations between variables were assessed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion:

EXTEM clot time (CT) and clot formation time (CFT) were prolonged in 87% and 45% patients whereas INTEM CT and CFT were prolonged in 36% and 73% patients, respectively. FIBTEM maximum clot firmness (MCF) was decreased in 30% patients. We observed significant correlation between fibrinogen concentration and ROTEM FIBTEM MCF (r = 0.94, P < 0.001). The SON platelet function (SON PF) showed good correlation with platelet count (r = 0.85, P < 0.001). We also found significant correlation between preoperative FIBTEM MCF and CDO in first 4 postoperative hours (r = 0.49, P = 0.004) and 24 postoperative hours (r = 0.52, P = 0.005). Receiver operating characteristic analysis demonstrated that SON PF and TEG maximum amplitude are highly predictive of thrombocytopenia below 100 × 109/L (area under the curve [AUC] - 0.97 and 0.92, respectively), while FIBTEM-MCF is highly predictive of hypofibrinogenemia (fibrinogen <150 mg/dL (AUC, 0.99).

Conclusion:

Cyanotic cardiac patients have preoperative coagulation abnormalities in ROTEM, TEG, and SON parameters. ROTEM FIBTEM is highly predictive of hypofibrinogenemia while SON PF is highly predictive of thrombocytopenia. ROTEM FIBTEM can be studied as a marker of increased postoperative CDO.

Keywords: Coagulopathies, cyanotic heart disease, point-of-care, rotational thromboelastometry, Sonoclot analyzer, thromboelastography

Introduction

Patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease (CCHD) have a significant tendency to bleed owing to the development of several coagulation abnormalities. These hemostasis abnormalities are attributed to thrombocytopenia, impaired platelet aggregation, overproduction of platelet microparticles, and shear stress due to blood hyperviscosity.[1,2] This hemorrhagic diathesis is further accentuated by hemodilution, platelet dysfunction, and loss of procoagulants during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).[3,4]

The hemostasis management after cardiac surgery is usually guided by standard laboratory tests such as platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and fibrinogen level.[5] However, the value of these tests has been questioned due to their prolonged turnaround time and poor bleeding predicting ability.[6]

In the last few years, viscoelastic point-of-care (POC) coagulation devices such as thromboelastography (TEG), rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM), and Sonoclot (SON) analyzer have been increasingly used in major surgeries for timely assessment and management of coagulopathies.[7,8]

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the coagulation profile of cyanotic cardiac patients with three POC testing devices (TEG, ROTEM, and SON analyzer). In addition, we assessed the correlation of standard laboratory coagulation tests and postoperative chest drain output (CDO) with the parameters of POC testing devices.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This is a prospective, observational pilot study. The original study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IECPG/394/5).

Selection of cases

Thirty-five patients of either gender, belonging to the American Society of Anesthesiologists Grade I–III, and undergoing elective cardiac surgery on CPB for CCHD were included in this study. Patients on preoperative anticoagulants, known coagulopathy, and patients undergoing cardiac surgery without involving CPB were excluded from the study.

Methodology

Routine preanesthetic examination was performed 1 day before surgery. The procedure was explained to the parents/patients, and written informed consent was obtained from them. Anesthetic, surgical, and CPB management was standardized in all patients. Anesthesia was induced with ketamine (1–2 mg/kg)/oxygen–sevoflurane mixture, fentanyl (2–3 μg/kg), and rocuronium bromide (0.8–1 mg/kg). Maintenance of anesthesia was achieved with isoflurane (0.5%–1.5%) in oxygen–air mixture with intermittent doses of fentanyl, midazolam, and pancuronium, which is the standard practice in our institute. All the patients were monitored with 5-lead ECG, SPO2, invasive blood pressure, central venous pressure, temperature, and urine output. Baseline activation clotting time (ACT) was noted before systemic heparinization with 4 mg/kg unfractionated heparin to achieve a target ACT of more than 400 s.

A membrane oxygenator was used for all patients during CPB. The CPB circuit was primed with lactated ringer solution 20 ml/kg, sodium bicarbonate (7.5%) 1 ml/kg, mannitol (20%) 0.5 g/kg, and 100 U/kg of unfractionated heparin. Packed red blood cells were added to pump volume during CPB, to maintain the target hematocrit of >30%. Myocardial preservation was achieved by administering Del Nido Cardioplegia. Blood gas analyses and ACT were performed intraoperatively at half hour intervals. Systemic pump flows were maintained between 120 and 200 ml/kg/min.

At the end of the surgery, all patients were reversed with protamine 1.3 mg/mg of heparin. Platelets and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) were transfused after coming off bypass to maintain hemostasis. All patients were shifted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for elective postoperative ventilation.

Parameters evaluated

Demographic and perioperative data such as age, sex, height, body weight, type of surgical procedure, and duration of CPB were noted in all patients. The baseline heart rate, blood pressure, central venous pressure, echocardiography, and routine hematological investigations were also noted. The blood samples for standard laboratory coagulation tests, TEG, ROTEM, and SON variables were taken after induction of anesthesia. Once the patient is shifted to the ICU, the postoperative CDO, duration of mechanical ventilation, and duration of ICU stay were noted. The total number of blood product units (packed red blood cell, FFP, platelets, and cryoprecipitate) transfused in the first 24 perioperative period were also noticed.

Sample collection

To identify possible baseline coagulation abnormalities, blood samples for TEG, ROTEM, SON, and standard laboratory coagulation tests were collected after induction of anesthesia. Blood samples for TEG and ROTEM analyses were drawn into a citrate-containing tube and analyzed after recalcification with 20 μL CaCl2. Blood samples for SON analysis were taken into plain syringes and transferred to the SON cuvette for immediate analysis. Blood samples for hemoglobin concentration, platelet counts, PT international normalized ratio (INR), aPTT, and fibrinogen concentration were collected and sent to the biochemistry laboratory in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid/citrate-containing tubes.

Statistical analysis

The quantitative variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The correlations between variables were assessed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated for POC test parameters to predict thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100 × 109/L) and hypofibrinogenemia (fibrinogen concentration <150 mg/dL). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the program SPSS for Windows, version 16.0 (IBM Corporation, USA).

Results

Patient demographics and perioperative data are shown in Table 1. A patient whose blood sample for SON got clotted before analysis and another patient who was operated for Glenn procedure with CPB standby were excluded later from the analysis. Hence, 33 patients were included for the final analysis.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, hematological and perioperative data (n=33)

| Variable | Mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 8.15±7.34 |

| Weight (kg) | 21.85±14.13 |

| Height (cm) | 114.21±28.91 |

| Sex (male/female) | 23/10 |

| Preoperative HCT (%) | 55.04±11.16 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 1.9±0.89 |

| PT (s) | 14.62±2.32 |

| aPPT (s) | 39.83±9.7 |

| Operation type | - |

| Total correction (TOF) | 21 |

| Glenn | 8 |

| Fontann | 2 |

| Ebstein repair | 1 |

| ASO | 1 |

| Duration of CPB (min) | 114.39±46.8 |

| PRBC used in 1st 24 h (units) | 1.68±1.57 |

| FFP used in 1st 24 h (units) | 1.95±2.25 |

| Platelets used in 1st 24 h (units) | 2.45±2.75 |

| Cryoprecipitate used in 1st 24 h (units) | 0.52±1.56 |

| CDO in 1st 4 postoperative hours (ml/kg/4 h) | 3.33±4.64 |

| CDO in 1st 24 postoperative hours (ml/kg/24 h) | 12.36±11.04 |

| Ventilation duration (h) | 30.66±93.51 |

| ICU duration (h) | 107±146.99 |

| Hospital duration (days) | 11.42±7.43 |

Data presented as mean±SD. HCT: Hematocrit, ASO: Arterial switch over, TOF: Tetralogy of fallot, CPB: Cardiopulmonary bypass, ICU: Intensive Care Unit, PRBC: Packed red blood cell, FFP: Fresh frozen plasma, CDO: Chest drain output, SD: Standard deviation, aPTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time, PT: Prothrombin time

Baseline coagulation profile

Platelet count below 150 × 109/L was found in 36% cyanotic patients. The preoperative hematocrit was elevated with mean (±SD) value of 55.04 ± 11.16. The PT (>15 s) and aPTT (>40 s) were prolonged in 33% and 48% patients, respectively. Hypofibrinogenemia (<150 mg/dL) was noticed in 36% of cyanotic patients.

ROTEM baseline parameters were found to be deranged. EXTEM clot time (CT) and clot formation time (CFT) were prolonged in 87% and 45% patients while INTEM CT and CFT were prolonged in 36% and 73% patients, respectively. Maximum clot firmness (MCF) EXTEM was reduced in 24% patients, and INTEM MCF was reduced in 33% patients. Fibrinogen profile was also deranged as FIBTEM MCF was decreased in 30% patients.

TEG also revealed coagulation abnormalities in cyanotic patients as clot kinetic (k) time was prolonged in 60% patients and alpha angle was found to be decreased in 54% patients. SON signature also showed prolonged ACT in 21% patients and reduced platelet function (PF) in 42% patients [Table 2].

Table 2.

Point of care (rotational thromboelastometer, thromboelastograph, sonoclot analyzer) tests parameters in cyanotic patients (n=33)

| POC tests parameters | Normal reference range[9,10] | Mean±SD in study population | Median (range) in study population | Percentage of patients with derranged parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXTEM CT (s) | 42-74 | 150.33±188.01* | 92 (55-1108) | 87 |

| EXTEM CFT (s) | 46-148 | 201.73±203.8* | 136 (67-1200) | 45 |

| EXTEM MCF (mm) | 49-71 | 54.33±11.7 | 56 (9-74) | 24 |

| INTEM CT (s) | 137-246 | 226.27±58.04 | 224 (29-376) | 36 |

| INTEM CFT (s) | 40-100 | 193.12±153.4* | 126 (43-613) | 73 |

| INTEM MCF (mm) | 52-72 | 54.12±8.35 | 54 (36-72) | 33 |

| FIBTEM A10 (mm) | 9-24 | 10.45±4.94 | 10 (4-25) | 36 |

| FIBTEM MCF (mm) | 9-25 | 11.88±5.28 | 11 (4-27) | 30 |

| SON ACT (s) | 96-182 | 118.45±41.93 | 110 (52-216) | 21 |

| SON CR (unit/min) | 15-45 | 13.41±10.7 | 11.4 (1.4-38) | 36 |

| SON PF | >1.6 | 1.5±0.89* | 1.7 (0-3.9) | 42 |

| TEG R (min) | 3-8 | 8.92±5.67* | 7.5 (3.5-26.2) | 45 |

| TEG K (min) | 1-3 | 4.31±2.6* | 3.5 (1.4-12.2) | 60 |

| TEG-α angle (°) | 55-78 | 43.37±18.31* | 44.3 (6-70.2) | 54 |

| TEG MA (mm) | 51-69 | 52.69±13.6 | 56.1 (12.3-67.3) | 24 |

*Derranged parameter (out of normal reference range). CT: Clotting time, CFT: Clot formation time, MCF: Maximum clot firmness, A10: Clot amplitude at 10 min, SON ACT: Sonoclot activated clotting time, CR: Clot rate, PF: Platelet function, TEG: Thromboelastograph, R: Reaction time, K: Clot kinetics, MA: Maximum amplitude, SD: Standard deviation, POC: Point-of-care

Correlation with conventional laboratory coagulation tests

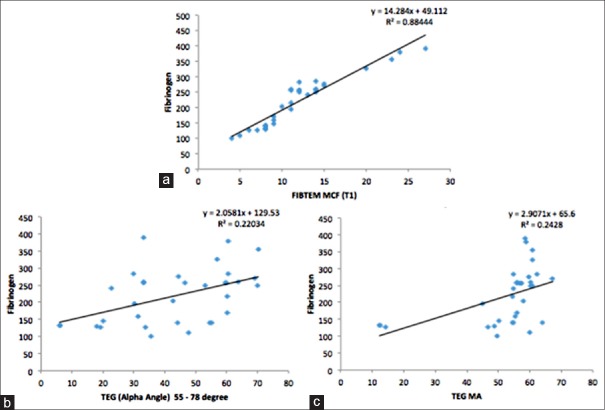

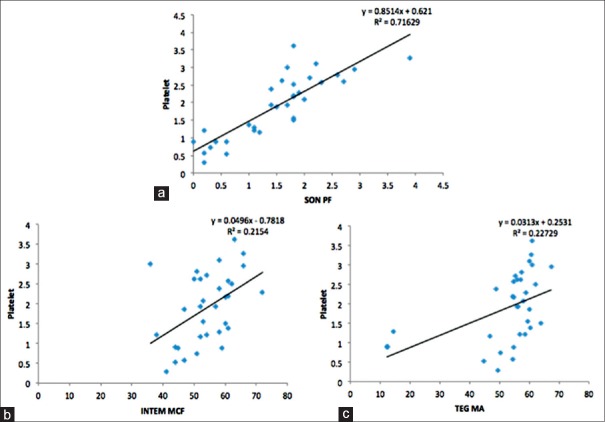

We observed positive correlation between various laboratory coagulation tests and parameters derived from POC devices [Table 3 and Figures 1 and 2]. A strong positive correlation was found between serum fibrinogen and ROTEM FIBTEM MCF (r = 0.94, P < 0.001). Serum fibrinogen also correlated with TEG alpha angle (r = 0.47, P = 0.006) and TEG maximum amplitude (MA) (r = 0.49, P = 0.004). A good correlation was observed between platelet count and SON platelet function (SON PF) (r = 0.85, P < 0.001), which also correlated with ROTEM INTEM MCF (r = 0.46, P = 0.007) and TEG MA (r = 0.48, P = 0.005). aPTT correlated with ROTEM INTEM CFT (r = 0.55, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Correlation of standard laboratory coagulation tests and point-of-care parameters

| Laboratory test | POC test parameters | Correlation (r) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrinogen | FIBTEM MCF (T1) | 0.940 | <0.001* |

| EXTEM MCF | 0.077 | 0.670 | |

| INTEM MCF | 0.162 | 0.368 | |

| TEG (alpha angle) | 0.469 | 0.006* | |

| TEG MA | 0.493 | 0.004* | |

| SON ACT | 0.127 | 0.481 | |

| SON CR | 0.266 | 0.135 | |

| Platelet | EXTEM MCF | 0.229 | 0.200 |

| INTEM MCF | 0.464 | 0.007* | |

| TEG MA | 0.477 | 0.005* | |

| SON PF | 0.846 | <0.001* | |

| aPTT | INTEM CT | 0.195 | 0.277 |

| INTEM CFT | 0.549 | <0.001* | |

| SON ACT | 0.215 | 0.230 | |

| SON CR | −0.202 | 0.260 | |

| TEG K | −0.131 | 0.467 | |

| TEG (alpha angle) | −0.081 | 0.654 | |

| PT | EXTEM CT | −0.034 | 0.851 |

| EXTEM CFT | 0.094 | 0.603 | |

| SON CR | −0.212 | 0.236 | |

| SON ACT | −0.112 | 0.535 | |

| TEG K | −0.114 | 0.528 | |

| TEG (alpha angle) | −0.298 | 0.092 |

*Statistically significant (P<0.05). CT: Clotting time, CFT: Clot formation time, MCF: Maximum clot firmness, SON ACT: Sonoclot activated clotting time, CR: Clot rate, PF: Platelet function, TEG: Thromboelastograph, K: Clot kinetics, MA: Maximum amplitude, POC: Point-of-care, aPTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time, PT: Prothrombin time

Figure 1.

Correlation between fibrinogen concentration and point-of-care testing parameters. (a) Fibrinogen and thromboelastography alpha angle, (b) fibrinogen and thromboelastography maximum amplitude, (c) fibrinogen and rotational thromboelastometry FIBTEM maximum clot firmness. Note a strong correlation (c) between fibrinogen and FIBTEM maximum clot firmness (r = 0.94)

Figure 2.

Correlation between platelet count, activated plasma thromboplastin time, and point-of-care parameters. (a) Platelet and Sonoclot platelet function, (b and c) platelet and rotational thromboelastometry FIBTEM maximum clot firmness (c) platelet and thromboelastography maximal amplitude

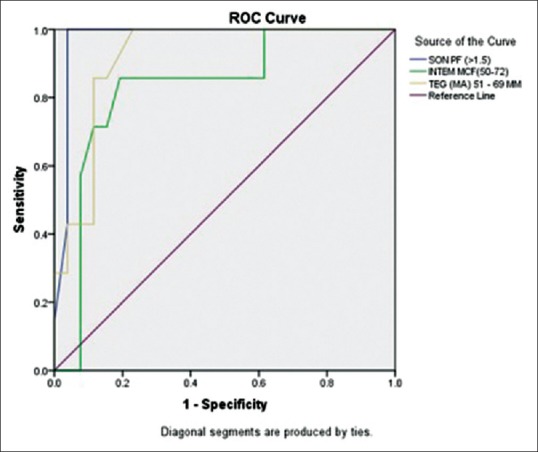

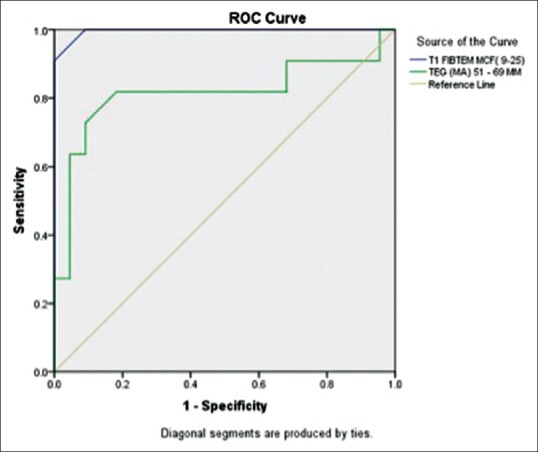

ROC analysis demonstrated that SON-PF was highly predictive while TEG MA and INTEM-MCF were predictive of thrombocytopenia of fewer than 100 × 109/L (area under the curve [AUC] - 0.97, 0.91, and 0.83, respectively) [Figure 3]. FIBTEM-MCF was found to be highly predictive, while TEG MA was predictive of fibrinogen concentration below 150 mg/dL (AUC - 0.99 and 0.82) [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of Sonoclot platelet function, INTEM-maximum clot firmness, and thromboelastography-maximum amplitude for predicting thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100 × 109/L)

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of FIBTEM-maximum clot firmness and thromboelastography-maximum amplitude for predicting hypofibrinogenemia (fibrinogen concentration <150 mg/dL)

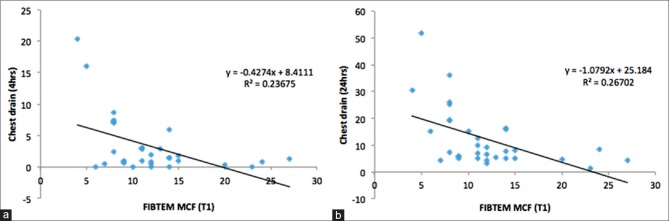

Correlation with postoperative chest drain output

We observed statistically significant correlation between ROTEM FIBTEM maximum clot firmness and CDO in first 4 postoperative hours (r = 0.49, P = 0.004) and 24 postoperative hours (r = 0.52, P = 0.005) [Figure 5]. However, no statistically significant correlation was found between CDO and other POC testing parameters.

Figure 5.

Correlation between rotational thromboelastometry FIBTEM maximum clot firmness and chest drain output in first 4 postoperative hours (r = 0.49) (a) and 24 postoperative hours (r = 0.52) (b)

Discussion

Several coagulation abnormalities have been described in cyanotic patients owing to multiple factors. Mauer et al. observed impaired platelet aggregation in 37.8% patients with CCHD.[11] This impaired platelet aggregation has been found to correlate with severity of hypoxemia and polycythemia in cyanotic patients.[2] These cyanotic patients have also been demonstrated to have lower antithrombin III activity and platelet count leading to a chronic compensated disseminated intravascular coagulation state.[1] Ismail and Youssef. observed increased platelet microparticles and P-selectin expression and lower platelet count, platelet aggregation, and glycoprotein IIb and IIIa expression in patients with CCHD as compared to acyanotic patients.[12]

In our study, we have analyzed coagulation abnormalities in cyanotic patients through TEG, ROTEM, and SON analyzer. We observed that 87% of cyanotic patients have deranged EXTEM profile (prolonged CT) and 73% of cyanotic patients have deranged INTEM profile (prolonged CFT), pointing to abnormalities in extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation system. Fibrinogen abnormalities were found in 36% patients as revealed by reduced ROTEM FIBTEM A10. Although 36% of patients had platelet count below 150 × 109/L, reduced PF (SON PF) was observed in 42% cyanotic patients through SON analyzer. TEG also revealed prolonged reaction time and abnormal clot kinetics in 45% and 60% cyanotic patients, respectively. Hence, in our study, we also observed abnormal coagulation profile in cyanotic cardiac patients in concordance with previous studies. Adding to the literature, we have studied these hemostatic abnormalities through bedside POC coagulation testing devices (TEG, ROTEM, and SON). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess coagulation abnormalities in cyanotic cardiac patients through the use of TEG, ROTEM, and SON analyzer simultaneously.

The use of these POC devices has grown rapidly in the past few decades, and their parameters have been found to correlate with various standard laboratory coagulation tests. Ogawa et al. compared different ROTEM parameters with standard coagulation tests in 26 patients, who were scheduled to undergo elective cardiac surgery. The author observed strong correlations between FIBTEM-amplitude at 10 min (A10) and fibrinogen level (r = 0.87; P < 0.001) and between EXTEM/INTEM-A10 variables and platelet count (r = 0.72 and 0.67, respectively; P < 0.001).[13] Similarly, Saxena et al. assessed the correlations between SON variables and conventional coagulation tests in patients with liver disease. They demonstrated significant positive correlation between PT-INR, APTT, and SONACT (r = 0.36, P < 0.008 [PT] and r = 0.43, P < 0.0015 [APTT]).[14]

In our study, we also found a significant positive correlation between standard laboratory coagulation tests and various POC tests parameters. We observed a strong positive correlation between fibrinogen concentration and ROTEM FIBTEM MCF (r = 0.94, P < 0.001). The SON PF showed good correlation with platelet count (r = 0.85, P < 0.001). ROTEM INTEM CFT correlated with aPTT (r = 0.46, P = 0.007). ROC analysis demonstrated that SON PF and TEG MA are highly predictive of thrombocytopenia below 100 × 109/L (AUC, 0.97 and 0.92, respectively), while FIBTEM-MCF is highly predictive of hypofibrinogenemia (fibrinogen <150 mg/dL) (AUC, 0.99).

Hence, these POC devices can be reliably used in cyanotic cardiac patients in place of standard laboratory tests. As results of POC tests are available in 20–40 min at bedside of patient, physicians need not wait for the result of laboratory tests to diagnose and manage coagulation abnormalities. Second, as fibrinogen concentration and PF can be reliably tested through ROTEM FIBTEM, and SON PF, a goal-directed blood transfusion can be started to avoid the use of unwanted blood products, decreasing transfusion-related complications, and hospital cost.

The diagnostic ability of POC instruments to predict postoperative bleeding is controversial.[15,16,17,18] Reinhöfer et al. studied the ability of ROTEM to monitor disturbed hemostasis and bleeding risk in patients with CPB. The authors noted that the positive predictive value and specificity of ROTEM variables such as CFT (71%, 94%) and FIBTEM (73%, 95%) to predict postoperative bleeding were significantly higher than conventional laboratory tests such as aPTT (56%, 72%) and PT (43%, 5%).[15]

In contrast, Davidson et al. observed that ROTEM thromboelastometry has poor positive predictive value (14.8%) to identify patients who bleed more than 200 mL/h in the early postoperative period after cardiac surgery. However, its negative predictive value was found to be good (100%). The authors realized that their study was not adequately powered to confirm its poor positive predictive value as the prevalence of bleeding in the early postoperative period was small (13.7%).[16]

In our study, we found statistically significant correlation between preoperative FIBTEM MCF and CDO in first 4 postoperative hours (r = 0.49, P = 0.004) and 24 postoperative hours (r = 0.52, P = 0.005). Hence, preoperative ROTEM FIBTEM can be studied as a marker of postoperative bleed. This can help stratify patients at risk of increased postoperative bleed. The hemostatic therapy (antifibrinolytic drugs and blood products) can be utilized in such patients.

Limitations

This pilot study has many limitations. First, the sample size of the study population is small. Second, we have studied coagulation profile of only cyanotic cardiac patients. The acyanotic cardiac patients or normal population should have been studied as a control group.

Conclusion

Cyanotic cardiac patients have preoperative coagulation abnormalities in ROTEM, TEG, and SON parameters. ROTEM FIBTEM is highly predictive of hypofibrinogenemia while SON PF is highly predictive of thrombocytopenia. ROTEM FIBTEM can be studied as a marker of increased postoperative CDO.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ghasemi A, Horri M, Salahshour Y. Coagulation abnormalities in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease: A literature review. Int J Pediatr. 2014;2:141–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horigome H, Hiramatsu Y, Shigeta O, Nagasawa T, Matsui A. Overproduction of platelet microparticles in cyanotic congenital heart disease with polycythemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1072–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Despotis GJ, Gravlee G, Filos K, Levy J. Anticoagulation monitoring during cardiac surgery: A review of current and emerging techniques. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1122–51. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199910000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolliger D, Szlam F, Levy JH, Molinaro RJ, Tanaka KA. Haemodilution-induced profibrinolytic state is mitigated by fresh-frozen plasma: Implications for early haemostatic intervention in massive haemorrhage. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:318–25. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuttall GA, Oliver WC, Ereth MH, Santrach PJ. Coagulation tests predict bleeding after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1997;11:815–23. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(97)90112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segal JB, Dzik WH. Transfusion Medicine/Hemostasis Clinical Trials Network. Paucity of studies to support that abnormal coagulation test results predict bleeding in the setting of invasive procedures: An evidence-based review. Transfusion. 2005;45:1413–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spalding GJ, Hartrumpf M, Sierig T, Oesberg N, Kirschke CG, Albes JM. Cost reduction of perioperative coagulation management in cardiac surgery: Value of “bedside” thrombelastography (ROTEM) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1052–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coakley M, Reddy K, Mackie I, Mallett S. Transfusion triggers in orthotopic liver transplantation: A comparison of the thromboelastometry analyzer, the thromboelastogram, and conventional coagulation tests. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20:548–53. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang T, Bauters A, Braun SL, Pötzsch B, von Pape KW, Kolde HJ, et al. Multi-centre investigation on reference ranges for ROTEM thromboelastometry. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2005;16:301–10. doi: 10.1097/01.mbc.0000169225.31173.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sankarankutty A, Nascimento B, Teodoro da Luz L, Rizoli S. TEG® and ROTEM® in trauma: Similar test but different results? World J Emerg Surg. 2012;7(Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-7-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauer HM, McCue CM, Caul J, Still WJ. Impairment in platelet aggregation in congenital heart disease. Blood. 1972;40:207–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ismail EA, Youssef OI. Platelet-derived microparticles and platelet function profile in children with congenital heart disease. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2013;19:424–32. doi: 10.1177/1076029612456733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa S, Szlam F, Chen EP, Nishimura T, Kim H, Roback JD, et al. A comparative evaluation of rotation thromboelastometry and standard coagulation tests in hemodilution-induced coagulation changes after cardiac surgery. Transfusion. 2012;52:14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxena P, Bihari C, Rastogi A, Agarwal S, Anand L, Sarin SK. Sonoclot signature analysis in patients with liver disease and its correlation with conventional coagulation studies. Adv Hematol 2013. 2013:237351. doi: 10.1155/2013/237351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reinhöfer M, Brauer M, Franke U, Barz D, Marx G, Lösche W. The value of rotation thromboelastometry to monitor disturbed perioperative haemostasis and bleeding risk in patients with cardiopulmonary bypass. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2008;19:212–9. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e3282f3f9d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson SJ, McGrowder D, Roughton M, Kelleher AA. Can ROTEM thromboelastometry predict postoperative bleeding after cardiac surgery? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22:655–61. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee GC, Kicza AM, Liu KY, Nyman CB, Kaufman RM, Body SC. Does rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) improve prediction of bleeding after cardiac surgery? Anesth Analg. 2012;115:499–506. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825e7c39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ti LK, Cheong KF, Chen FG. Prediction of excessive bleeding after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: The influence of timing and heparinase on thromboelastography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16:545–50. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2002.126945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]