Abstract

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is the cause of varicella (chickenpox) and zoster (shingles). Varicella is a primary infection that spreads rapidly in epidemics while zoster is a secondary infection that occurs sporadically as a result of the reactivation of previously acquired VZV. Reactivation is made possible by the establishment of latency during the initial episode of varicella. The signature lesions of both varicella and zoster are cutaneous vesicles, which are filled with a clear fluid that is rich in infectious viral particles. It has been postulated that the skin is the critical organ in which both host-to-host transmission of VZV and the infection of neurons to establish latency occur. This hypothesis is built on evidence that the large cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (MPRci) interacts with VZV in virtually all infected cells, except those of the suprabasal epidermis, in a way that prevents the release of infectious viral particles. Specifically, the virus is diverted in an MPRci-dependent manner from the secretory pathway to late endosomes where VZV is degraded. Because nonepidermal cells are thus prevented from releasing infectious VZV, a slow process, possibly involving fusion of infected cells with their neighbors, becomes the means by which VZV is disseminated. In the epidermis, however, the maturation of keratinocytes to give rise to corneocytes in the suprabasal epidermis is associated uniquely with a downregulation of the MPRci. As a result, the diversion of VZV to late endosomes does not occur in the suprabasal epidermis where vesicular lesions occur. The formation of the waterproof, chemically resistant barrier of the epidermis, however, requires that constitutive secretion outlast the downregulation of the endosomal pathway. Infectious VZV is therefore secreted by default, accounting for the presence of infectious virions in vesicular fluid. Sloughing of corneocytes, aided by scratching, then aerosolizes the virus, which can float with dust to be inhaled by susceptible hosts. Infectious virions also bathe the terminals of those sensory neurons that innervate the epidermis. These terminals become infected with VZV and provide a route, retrograde transport, which can conduct VZV to cranial nerve (CNG), dorsal root ganglia (DRG), and enteric ganglia (EG) to establish latency. Reactivation returns VZV to the skin, now via anterograde transport in axons, to cause the lesions of zoster. Evidence in support of these hypotheses includes observations of the VZV-infected human epidermis and studies of guinea pig neurons in an in vitro model system.

1 Introduction

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is one of the eight herpesviruses that infect humans and is, arguably, the most infectious (Gershon et al. 2008a; Ross et al. 1962). Primary VZV infection is manifested as varicella (chickenpox). During this illness, VZV becomes latent in dorsal root (DRG), cranial nerve (CNG), and enteric ganglia (EG; see below) where VZV remains for life. In about 30% of individuals with latent VZV, the virus reactivates to cause a secondary infection, zoster (shingles) (Gershon et al. 2008a). Varicella can thus be acquired from patients with zoster, but zoster, which arises only after reactivation, cannot be acquired from patients with varicella or zoster. Latency and reactivation provide VZV with an evolutionary advantage. Because varicella is so infectious, it sweeps rapidly through populations in epidemics that exhaust the supply of susceptibles. Latency, however, allows VZV to persist in a host for years despite the host's immunity. Reactivation at a later date, after a new supply of susceptibles has been regenerated, allows VZV to emerge and transmit infection to a new generation. In this way VZV, which does not have an animal reservoir, can perpetuate itself.

VZV is a highly successful parasite. It is in its evolutionary interest, as it is in the interest of any parasite, to do as little damage as possible to the host that provides it with a residence. Despite its highly infectious nature, VZV spreads very slowly within infected individuals, allowing time for adaptive immunity to develop before the infection crosses the clinical threshold. Immunity of the hosts, within which VZV is latent, helps to ensure that providing VZV with a safe haven does not compromise the host's survival. The highly infectious nature of VZV makes its slow in vivo spread and long incubation period seem counterintuitive, even paradoxical. In fact, however, the behavior of VZV when grown in vitro bears no resemblance to its ferocious host-to-host spread. The same virus that sweeps with amazing speed and vehemence through a susceptible population of children (Ross et al. 1962) spreads almost reluctantly and slowly through a population of cultured cells. Most of the cells that are infected with VZV in vitro, moreover, do not secrete infectious virions; in vitro spread requires the very slow process of cell-to-cell contact (Gershon et al. 2007), which may or may not involve fusion of infected cells with their neighbors (Reichelt et al. 2009). Medium in which infected cells are grown is not infectious (Gershon et al. 2007). A similar form of slow cell-to-cell transmission could account for the slow intrahost dissemination of VZV in vivo.

What accounts for the profound difference between the rapid host-to-host and the slow cell-to-cell spread of VZV? It has been proposed that free virions are responsible for host-to-host transmission of VZV, while cell-to-cell contact is the means by which VZV grows and disseminates within an infected individual (Chen et al. 2004). This hypothesis implies that infectious viral particles emerge only at the site where VZV is transmitted to new hosts, which is the skin. Infected keratinocytes are postulated to be veritable VZV factories, which uniquely churn out infectious virions. The survival advantage to VZV is that slow spread within a newly infected host prevents the virus from overwhelming that host with a flood of infectious particles. The slow intrahost dissemination delays the emergence of dangerous free virions until the adaptive immune response has been marshaled. By the time infectious virions are being mass-produced in keratinocytes, the defenses of the host are sufficiently ready to assure that the host, together with its reservoir of latent virions, survives. On the other hand, sloughing of infected keratinocytes allows a cornucopia of infectious virions to waft away and drift in the wind to where they can be inhaled by unwitting hosts.

The hypothesis that cell-to-cell spread is responsible for dissemination of VZV within infected hosts began with observations that sought to understand the profound cell association of VZV in vitro. Morphological and other studies demonstrated that nucleocapsids assemble within the nuclei of infected cells. Virions were found to acquire an envelope by budding through the inner nuclear membrane (Gershon et al. 1994). This process delivers the just-enveloped virion to the peri-nuclear cisterna, which is continuous with the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER). Curiously, however, electron microscopic radioautographic studies revealed that the virions in this location were not labeled after any time of chase following exposure to a pulse of 3H-mannose (Zhu et al. 1995). This observation suggests that the glycoproteins (gps) with N-linked oligosaccharides of the final viral envelope are not present in virions that emerge from the nuclei of infected cells. In contrast, the membranes of the RER were labeled by 3H-mannose almost immediately, suggesting that N-glycosylation of viral gps, like that of cellular gps, occurs cotranslationally in the RER. At later times of chase, no movement of radioactivity back to the nucleus was ever detected; rather, later times of chase revealed a movement of labeled gps to the Golgi apparatus and trans-Golgi network, where virions became labeled. The virions that bud out of the nucleus to reach the cisternal space were observed to fuse almost immediately with the RER. This fusion delivers the nucleocapsids to the cytosol, while the original nuclear membrane-provided viral envelope is incorporated into the RER. This process requires that VZV undergo a secondary envelopment during which tegument proteins, which lack signal sequences and are synthesized by free polyribosome in the cytosol, can be incorporated into the completed virions.

VZV receives tegument and its final envelope in the TGN. The TGN is thus a meeting place of the envelope proteins that have been transported from the RER with tegument proteins and nucleocapsids. The secondary envelopment of VZV that occurs in the TGN critically involves VZV glycoprotein I (gI) (Wang et al. 2001). Cellular and viral proteins are sorted within the cisternae of the TGN, which are caused to form thin semicircular sacs. Viral proteins segregate to the concave surfaces of these sacs and cellular proteins, including large cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptors (MPRcis) (Goda and Pfeffer 1988), segregate to the convex surface (Gershon et al. 1994; Zhu et al. 1995). These TGN sacs wrap around nucleocapsids and fuse to envelop them. The original concave surface of the TGN wrapping cisternae becomes the viral envelope, while the convex surface becomes an MPRci-rich transport vesicle. The newly enveloped virions are then diverted to late endosomes. The environment that the virus encounters within late endosomes is acidic, which is deadly to VZV (Gershon et al. 1994). The morphology of VZV is degraded within the late endosomes, and subsequent exocytosis leads to the release of degraded virions, which can be visualized extracellularly by electron microscopy (EM) (Carpenter et al. 2009; Gershon et al. 1994). The post-Golgi degradation of the virions thus appears to render them noninfectious when they are ultimately released.

The critical step in the process of viral exit is the diversion of newly enveloped VZV from the secretory pathway to late endosomes, which may be due to the presence of mannose 6-phosphpate (Man 6-P) residues in at least four gps of the viral envelope (Gabel et al. 1989). Man 6-P interacts with the MPRci. MPRcis are present in the transport vesicles that arise with the virions in specialized cisternae of the TGN where VZV is enveloped (Chen et al. 2004; Gershon et al. 2008b). By interacting with MPRcis, newly enveloped virions can follow the MPRci's itinerary during their post-Golgi transport through the cytoplasm of infected cells. MPRcis traffic from the TGN, not only to late endosomes, but also to the plasma membrane (Brown et al. 1986; Gabel and Foster 1986; Kornfeld 1987), where they act as receptors that mediate endocytosis of ligands, such as lysosomal enzymes, that contain Man 6-P residues (Gabel and Foster 1986; Yadavalli and Nadimpalli 2009).

The idea that MPRcis play a critical role in the intracellular trafficking of VZV has been supported by experiments that utilized expression of antisense cDNA or siRNA to generate five stable human cell lines that were deficient in MPRs (Chen et al. 2004). All five of these lines secreted lysosomal enzymes, indicating that their ability to divert Man 6-P-bearing proteins from the secretory pathway was defective. All five lines also released infectious virions when infected with cell-associated VZV. The addition of the simple sugar Man 6-P, moreover, was found to inhibit the infection of cells by cell-free VZV, which is consistent with the idea that Man 6-P can compete with the gps of the viral envelope for binding to cell surface MPRcis (Gabel et al. 1989). Man 6-P, however, cannot interfere with the infection of cells by cell-associated VZV, which probably requires cell fusion, and has been linked to the interaction of VZV gE with insulin degrading enzyme (Li et al. 2006). All five of the MPR-deficient lines generated with antisense cDNA or siRNA resisted infection by cell-free but not cell-associated VZV (Chen et al. 2004). That observation supports the idea that plasmalemmal MPRcis are necessary for infection of cells by cell-free VZV. MPRcis are known to be responsible for the receptor-mediated endocytosis of Man 6-P-bearing ligands, such as lysosomal enzymes (Canfield et al. 1991; Duncan and Kornfeld 1988; Johnson et al. 1990; Kornfeld 1987). Cell surface MPRcis may also mediate the endocytosis of cell-free VZV, which is critically involved in viral entry (Hambleton et al. 2007). It is therefore probable that intracellular MPRcis divert newly enveloped VZV to late endosomes, while MPRcis of the plasma membrane participate in infection of target cells by cell-free VZV.

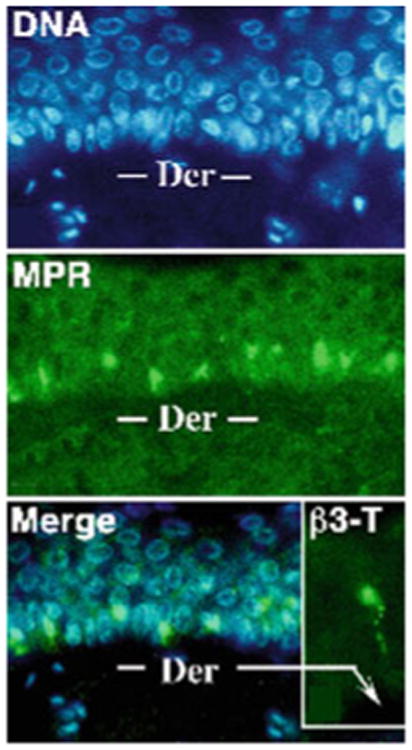

The function of MPRcis relates to the transmission of VZV because MPRcis are naturally downregulated in the suprabasal layers of the epidermis in human skin (Chen et al. 2004) (Fig. 1). This downregulation is a property of normal keratinocyte maturation, which is a complex process that VZV has evolved to exploit. Keratinocytes are generated through the proliferation and differentiation of stem cells in the basal layer (stratum germinativum) of the epidermis (Koster 2009). The stem cells give rise to transit amplifying cells, also in the basal layer, which undergo multiple rounds of mitoses before they initiate the process of terminal differentiation. That process occurs suprabasally and begins when the transit amplifying cells permanently withdraw from the cell cycle. The postmitotic keratinocytes continue to mature as they move suprabasally in columns called epidermal proliferation units. Maturing keratinocytes ultimately differentiate into corneocytes or squames, which form the cellular component of the waterproofing barrier of the skin (Proksch et al. 2008). Mature corneocytes are the nonliving remains of cells that have jettisoned both their nucleus and their cytoplasmic organelles. They are essentially envelopes that are filled with arrays of intermediate filaments (composed of cytokeratins), which are organized into tight bundles by the essential protein, fillagrin. Corneocytes are stably connected to one another by corneodesmosomes. The cornified cell envelope has both protein and lipid components. Proteins include involucrin, loricrin, and trichohyalin, which are tightly crosslinked both by disulfide bonds and by N-ε-(γ-glutamyl)lysine isopeptide bonds. The formation of these bonds is catalyzed by transglutaminases. The lyso-somal enzyme, cathepsin D, which is an aspartase protease, is required to cleave transglutaminase 1 to liberate its active 35-kDa form.

Fig. 1.

The MPRci is downregulated during natural maturation of keratinocytes in the suprabasal epidermis. A section of skin is stained to demonstrate DNA (blue fluorescence) with bisbenzimide and MPRci immunoreactivity (green fluorescence). Note the absence of MPRci immunoreactivity in the superficial layers of the suprabasal epidermis and its strong presence in the basal layer. Inset: Intraepidermal nerve fiber demonstrated with antibodies to the neuronal marker β3-tubulin

Enveloped corneocytes adhere strongly, not only to one another, but also to the intercellular matrix that their predecessors have secreted and to which the cornified envelope becomes covalently linked. These predecessors, in the upper stratum spinosum and the stratum granulosum, contain cells with so-called lamellar bodies, which contain lipid components of the epidermal barrier. Lamellar bodies are Golgi-derived vesicles that contain polar lipids, glycophospholipids, free sterols, phospholipids, catabolic enzymes, and β-defensin 2. The contents of lamellar bodies are secreted by exocytosis within the stratum granulosum despite the continuing progression of the cells of this layer toward their impending death. The lipids secreted from lamellar bodies become modified and arranged into lamellae that are parallel to the surfaces of cells in the matrix. Extracellular enzymes convert secreted polar lipids into nonpolar products, secreted glycosphingolipids into ceramides [amide-linked fatty acids containing a long-chain amino alcohol (sphingoid base)], and secreted phospholipids into free fatty acids. The stratum corneum ultimately acquires at least nine ceramides, which become covalently bound to the cornified envelope, primarily to involucrin. The cornified envelope and the extracellular matrix thus forms a tightly linked scaffold that waterproofs the epidermis and confers upon it an extraordinary degree of mechanical stability and chemical resistance. The process that constructs this essential barrier between the body and the outside world is thus a remarkable process in which secretion continues despite the inactivation of housekeeping functions in cells marked for death. The default secretory pathway thus outlasts MPRci receptors. This is the phenomenon that evidently provides VZV with the escape hatch that it needs to evade diversion to endosomes and to emerge intact. Despite their anchoring, moreover, corneocytes are dead cells that must be replaced. Desquamation is thus an on-going process. A person moving on leaves an invisible cloud of shed skin behind. If the epidermis is infected with VZV, this cloud is laden with infectious virions.

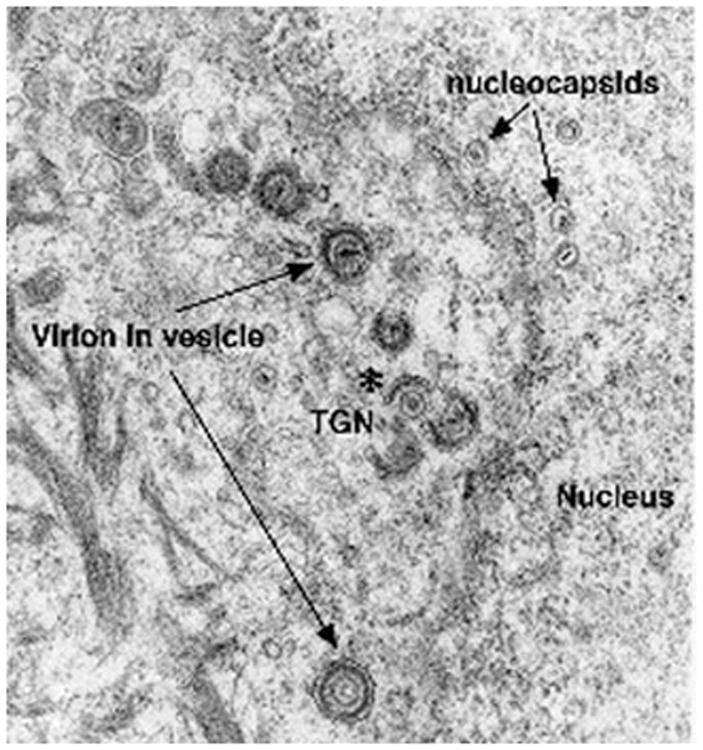

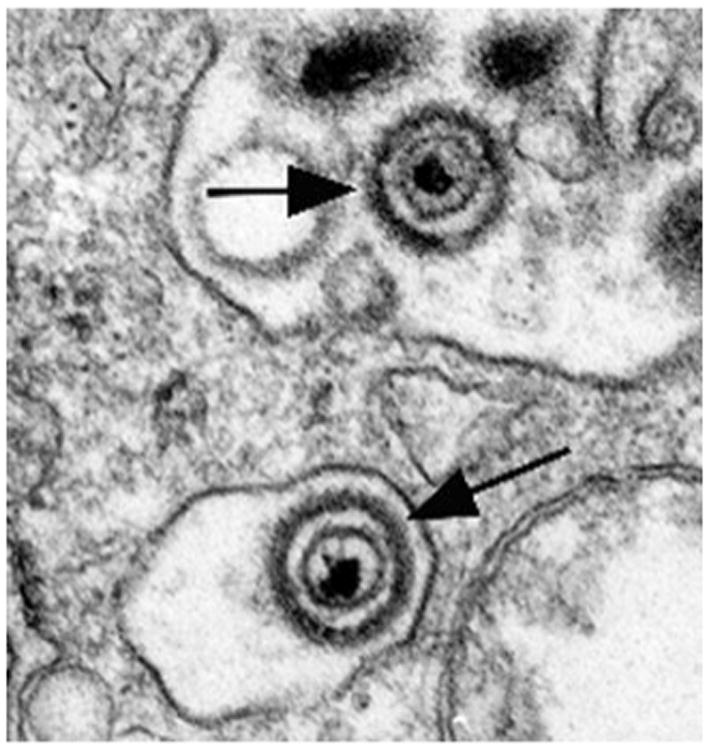

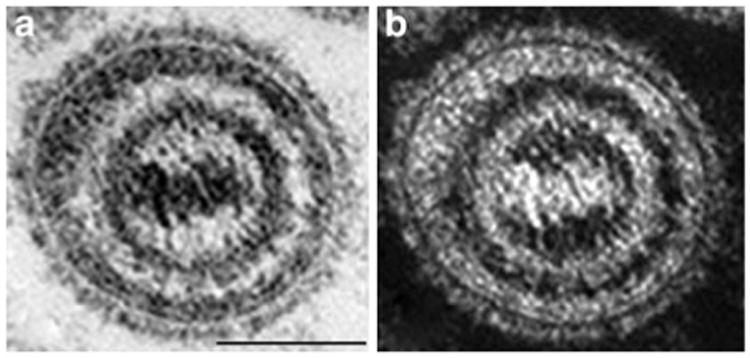

Biopsies from VZV-infected human skin, both in varicella and zoster, have revealed that although VZV is concentrated and degraded in the endosomes of basal cells, within which MPRci-mediated diversion to late endosomes is intact, VZV is not degraded in the infected cells of the suprabasal epidermis (Fig. 2), within which MPRci have been downregulated (Chen et al. 2004). Instead, intact virions are packaged singly in small vesicles (Fig. 2) within the MPRci-deficient suprabasal cells and are released intact into the intercellular space (Fig. 3). These spaces expand to form the vesicular lesions of varicella and zoster, within which perfectly formed intact virions that are highly infectious are concentrated. Consistent with the release of VZV from maturing suprabasal keratinocytes, these intraepidermal lesions, particularly early ones, are typically found within the suprabasal layers of the epidermis (Fig. 4). Until intraepidermal vesicles break down, the waterproofing provided by the corneocytyes of the stratum corneum provides a roof over intravesicular pockets of virion-rich intercellular fluid. Lesions may expand or be enlarged by superinfection, but most epidermal vesicles do not include the basal layer of the epidermis, the underlying basal lamina, or the dermis. These observations support the hypothesis outlined earlier that the natural loss of MPRci expression in the maturing cells of the suprabasal epidermis causes these cells to fail to divert VZV to late endosomes. Because constitutive secretion is the default pathway of post-TGN transport, the downregulation of the MPRci causes maturing keratinocytes to secrete infectious VZV constitutively instead of diverting newly enveloped virions to late endosomes. Desquamation of the epidermis, natural or induced by scratching, would break the last remaining roof of corneocytes over intraepidermal vesicles and allow masses of accumulated infectious virions to aerosolize and be inhaled by a susceptible host. This process, if correct, would account for the highly effective and rapid host-to-host spread of VZV. The contrasting slow cell-to-cell spread of VZV in all sites except the superficial epidermis restrains what would otherwise be a lethal VZV infection and provides the host with the time needed to mount an adaptive immune response. Varicella is thus usually a relatively benign disease, although it is certainly not benign in adults (Gregorakos et al. 2002; Wallace et al. 1993), individuals who are immunodeficient and unable to mount an immune response (Wood et al. 2008), or in pregnant mothers who transmit VZV to fetuses in whom adaptive immunity is immature (Auriti et al. 2009; Gershon et al. 2008a; Mustonen et al. 2001; Sauerbrei and Wutzler 2000).

Fig. 2.

Within superficial keratinocytes of the VZV-infected suprabasal epidermis, VZV is enveloped in the TGN and packaged singly in transport vesicles. An electron micrograph illustrates the suprabasal epidermis of the biopsied skin of a patient with varicella. All stages of viral envelopment can be seen in the infected keratinocytes. Unenveloped nucleocapsids can be seen in the nucleus and nucleocapsids are being enveloped (asterisk) by specialized cisternae of the TGN. Transport vesicles (arrows) each contain a single enveloped virion. Accumulating cytokeratin filaments are visible at the lower left in the cytoplasm of the keratinocytes

Fig. 3.

Keratinocytes of the suprabasal layers of the VZV-infected epidermis secrete intact virions to the extracellular space. Two extracellular virions are illustrated (arrows)

Fig. 4.

Intact virions are found in the fluid extracted from within vesicular epidermal lesions of patients with varicella. Vesicular fluid was drawn from an epidermal vesicle of a patient with varicella and prepared for electron microscopic examination. A virion is illustrated at high magnification and imaged in brightfield (a) and darkfield (b) to emphasize the near-perfect viral morphology. Note the spikes on the viral envelope, the complexity of the underlying tegument, and the apparent connections between the nucleocapsid and the tegument. The marker = 100 nm

Because neurons from DRG and CNG send axonal projections into the epidermis (McArthur et al. 1998), the intraepidermal axons of DRG and CNG neurons are in a strategically favored place from the point of view of VZV. The infectious virions that suprabasal keratinocytes release, of necessity, bathe the nerve endings that happen to be included within the suprabasal vesicular lesions that form in varicella. By infecting these nerve fibers, VZV can gain access via retrograde transport to the cell bodies of DRG and the CNG, such as the trigeminal, which project to the epidermis. Once in the DRG and CNG, VZV can establish latency. Intraepidermal neuronal projections, therefore, can provide conduits between the skin and ganglia that VZV can utilize for travel secure from the predations of immune effectors. As long as VZV remains latent in neurons, moreover, the virus is shielded from the host's immune response. This protection requires that the latently infected neurons survive and not express viral antigens on their surface. Until reactivation occurs, the latent virus and the host can coexist in harmony. After reactivation, however, VZV can return to the epidermis by way of its axonal conduit, this time by anterograde transport. The epidermis again becomes infected, now with zoster. Viral antigens are expressed on the surfaces of neurons (Lungu et al. 1995), which probably die as a result of reactivation (Chen et al. 2003; Gowrishankar et al. 2007; Nagashima et al. 1975; Zerboni et al. 2005). Certainly, in model systems, reactivation of VZV is rapidly lethal to the neurons in which reactivation takes place (Chen et al. 2003; Gershon et al. 2008b). The infection of the epidermis that results from reactivation is usually limited by the host's immune response, but it is painful and can be followed by the neuropathic pain of post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) (Mueller et al. 2008; Nagel and Gilden 2007). The reactivated virus, moreover, is once again able to exploit the downregulation of MPR in the epidermis. It can again undergo constitutive secretion, reach vesicular fluid, and spread via desquamation from the skin to find new hosts. The disorder leaves the original host highly discomforted but alive.

In adults and children, varicella is spread predominately by the airborne route from the epidermal lesions of individuals with varicella or zoster (Breuer and Whitley 2007). Spread from the respiratory tract cannot be ruled out, but unlike respiratory infections that are transmitted by droplets (Morawska 2006; Yu et al. 2004), varicella is not accompanied by coughing and sneezing, which propel infectious droplets into the air (Gershon et al. 2008a). VZV is difficult to isolate from respiratory secretions although it is easily isolated from fresh skin vesicles (Gold 1966). Virions in skin vesicles are of an appropriate size (200 nm) to travel in air. Although VZV DNA has been identified in air samples from patient rooms by PCR for many days (Sawyer et al. 1993; Yoshikawa et al. 2001), there is no evidence that this DNA is infectious. Finally, only vaccinated persons with skin lesions are capable of transmitting the Oka vaccine strain to other individuals (Sharrar et al. 2000; Tsolia et al. 1990). Infectious virions, produced, as described earlier, in the superficial epidermis, shed from the desquamating skin and travel through the air with dust particles to reach respiratory surfaces of susceptible hosts to cause infection. Infection is initiated in tonsilar T cells (Ku et al. 2002) and may spread to tonsilar keratinocytes for additional multiplication.

During an incubation period of 10–21 days, during which the location of VZV is not completely clear (although the virus is traditionally said to proliferate in the lungs and the liver), a viremia occurs; VZV circulates within infected T lymphocytes (Koropchak et al. 1989). The T cells home to the skin and infect the stem cells and transit amplifying cells of the stratum germinativum, from which infection can disseminate by cell-to-cell spread to reach the suprabasal layers of the epidermis. Modulation of viral replication by innate immunity in the skin has also been postulated to prevent VZV infection from overwhelming its host (Ku et al. 2004). The intraepidermal proliferation of VZV, with associated inflammation and death of infected cells, causes the vesicular rash of varicella.

It has been proposed that VZV establishes latency because the free virions are uniquely released from the infected suprabasal keratinocytes that have downregu-lated MPRci expression but still secrete, bathe, and infect intraepidermal sensory nerve endings. Virions (or infectious components derived from them) are transported in the retrograde direction to nerve cell bodies in DRG and CNG where they establish latency (Gershon et al. 2008b). Zoster occurs when VZV reactivates from latency and proliferates in neuronal perikaya. Virions, or, as in the case of herpes simplex, viral components that can be assembled into virions within axon terminals (Diefenbach et al. 2008), are transported, now in the anterograde direction, back down the axons to the epidermis, where they again infect keratinocytes and give rise to a vesicular rash. Viremic dissemination, however, is unusual in zoster because reactivation usually occurs in at least partially immune host.

Ganglion cells within which VZV is latent, can survive for years. Only a limited set of viral genes is transcribed during latency; these encode immediate early and early proteins (ORF4, 21, 29, 62, 63, 40, 66) but gps are not expressed (Cohrs et al. 1995, 1996, 2003; Cohrs and Gilden 2003; Croen et al. 1988; Gershon et al. 2008b; Grinfeld and Kennedy 2004; Grinfeld et al. 2004; Kennedy et al. 2000, 2001; Lungu et al. 1998). Neurons in which VZV reactivates display lytic infection. They thus transcribe a full set of viral genes, including ORF61 and gps; then they die (Chen et al. 2003; Head and Campbell 1900). The death of neurons in which VZV reactivates causes sensory deficits (Head and Campbell 1900), although these are usually mild and compensated by expansion of the receptive fields of remaining neurons (Feller et al. 2005; Gershon et al. 2008b). Neuronal death, however, is followed, about 15% of the time (depending on the age of the patient), by the debilitating and often long-lasting neuropathic pain of PHN (Dworkin et al. 2007; Feller et al. 2005; Fields et al. 1998).

Research on the consequences of VZV infection in neurons has been hampered by the lack of a suitable animal model. Investigators have had limited success in infecting guinea pig DRG (Arvin et al. 1987; Lowry et al. 1992, 1993; Matsunga et al. 1982; Myers et al. 1980, 1985, 1991; Sato et al. 2003) and, although latent infection of ganglia has been achieved in cotton rats (Cohen et al. 2007) and rats (Rentier et al. 1996), VZV has not been reactivated in either of these animals. We have furthered our own ability to analyze the life cycle of VZV by developing an in vitro model that utilizes enteric neurons isolated from the guinea pig small intestine (Chen et al. 2003; Gershon et al. 2008b). The advantage of the ENS for this purpose is that its structure resembles that of the brain (Gershon 2005). Fibroblasts and connective tissue are not present within EG. Instead, enteric neurons are supported by glia, which resemble CNS astrocytes (Gershon and Rothman 1991). As a result of their glia-dependent integrity, ganglia remain intact when the bowel is dissociated with collagenase (Chen et al. 2003; Gershon et al. 2008b). EG can then be selected from a collagenase-dissociated suspension of enteric cells with a micropipette and isolated as relatively pure preparations of neurons and glia. When isolated EG are exposed to cell-free VZV, latent infection of neurons results. The same VZV transcripts and proteins that are expressed during latency in DRG and CNG are also expressed in latently infected enteric neurons, which survive for as long as cultures can be maintained. In contrast, when connective tissue cells are present at the time of inoculation (either because infection is passed with cell-associated VZV or because enteric fibroblasts have been included in the original cultures), lytic infection of the neurons occurs. Such neurons now express the full set of VZV proteins and die within 48–72 h.

After latent VZV infection has been established in cultured enteric neurons, reactivation cannot be initiated by adding fibroblasts to the cultures (Chen et al. 2003; Gershon et al. 2008b). The ability of fibroblasts to cause VZV infection of enteric neurons to be lytic rather than latent requires that the fibroblasts be present at the time neurons are first exposed to VZV. It has been postulated that fibroblasts that are present at the time of inoculation become infected with VZV and then fuse with neighboring neurons. Such a fusion would allow a nonstructural protein to gain entrance to the infected neurons at the moment of their infection. This idea was tested and supported by expressing the nonstructural VZV protein, ORF61p (Kinchington et al. 1995), or its HSV orthologue, ICP0 (Moriuchi et al. 1993), in latently infected enteric neurons. Both ORF61p and ICP0 proved to be able to reactivate VZV (Chen et al. 2003; Gershon et al. 2008b); the late VZV gene products, including the gps, were now produced and neurons, which had harbored latent VZV for weeks, died within 48–72 h of reactivation. Before their death, neurons were found by EM to contain intact virions (identified as VZV by showing gE immunoreactivity in their envelopes); moreover, following reactivation, but not during latency, enteric neurons were able to transmit VZV infection to cocultures of human melanoma cells (MeWo) in culture. It has been suggested that ORF61p acts as a switch that triggers the lytic cascade (Gershon et al. 2008b). The observation that ORF61p contributes to the virulence of VZV at cutaneous sites of VZV replication is consistent with this suggestion (Wang et al. 2009).

It might seem odd that VZV should recapitulate its life cycle in cultures of enteric neurons, which do not project to the epidermis, rather than in those of DRG or CNG, which do so. At first, it was thought that EG could be infected with VZV because the ENS, like DRG and CNG, contains primary afferent neurons (Wang et al. 2009), for which VZV was considered to be trophic. This idea turned out to be incorrect. VZV infects all enteric neurons, not only those that display sensory markers (Chen et al. 2003; Gershon et al. 2008b). The key is that enteric neurons can be isolated free of contaminating connective tissue cells, whereas neurons from DRG and CNG cannot. Further studies, moreover, established unexpectedly that the ENS actually is a natural target of VZV and becomes infected in human hosts (Chen et al. 2009; Gershon et al. 2008b). Transcripts encoding VZV proteins that are expressed during latency (ORFps 4, 21, 62, or 63) were detectable in 88% of 31 specimens of adult human gut obtained during surgery for unrelated clinical indications. This observation has recently been confirmed by demonstrating VZV DNA, as well as transcripts encoding latency-associated proteins, in specimens of gut obtained at surgery from children with a history of varicella and from those with a history of varicella vaccination (Gershon et al. 2009). In contrast, no VZV DNA or transcripts encoding VZV were detected in specimens of newborn bowel. These observations suggest that VZV can and does become latent in human enteric neurons after varicella or after administration of the varicella vaccine. The observation that varicella vaccination, which is typically delivered to the skin of the arm, can lead to latency in EG strongly suggests that, in contrast to expectations, vaccination is associated with a viremia. This suggestion is further supported by observations made in autopsy specimens obtained from vaccinated children dying suddenly of unrelated causes, that viral DNA and transcripts are found not only in ganglia innervating the vaccination site, but also bilaterally in distant ganglia (Gershon et al. 2009). Still to be determined, however, is whether the VZV that establishes latent infection can only be delivered to ganglia by axons that acquire VZV released as infectious particles in the skin, or whether they can also become infected by the T lymphocytes that carry VZV during a viremia (Abendroth et al. 2001; Asanuma et al. 2000; Koropchak et al. 1989; Ku et al. 2002; Moffat et al. 1995; Schaap et al. 2005). There is evidence that VZV-infected lymphocytes release infectious cell-free viral particles (Moffat et al. 1995), although this evidence is not universally accepted and contrary data have also been reported (Soong et al. 2000). If VZV-infected T lymphocytes do release infectious virions, then they should be as able as keratinocytes to infect neurons in a manner that can establish latency. If not, then either cell-free VZV is not required for the establishment of latency in DRG and CNG, or a lymphocyte-borne viremia might cause subclinical infections of keratinocytes in many regions of the skin. Should that occur, then sufficient virions might be secreted by VZV-infected keratinocytes to infect intraepidermal nerves, even in the absence of rash.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants NS12969, AI27187, and AI24021.

References

- Abendroth A, Lin I, Slobedman B, Ploegh H, Arvin AM. Varicella-zoster virus retains major histocompatibility complex class I proteins in the Golgi compartment of infected cells. J Virol. 2001;75:4878–4888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4878-4888.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvin AM, Solem S, Koropchak C, Kinney-Thomas E, Paryani SG. Humoral and cellular immunity to varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein, gpI, and to a non-glycosulated protein p170, in strain 2 guinea pigs. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:2449–2454. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-9-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma H, Sharp M, Maecker HT, Maino VC, Arvin AM. Frequencies of memory T cells specific for varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus by intracellular detection of cytokine expression. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:859–866. doi: 10.1086/315347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auriti C, Piersigilli F, De Gasperis MR, Seganti G. Congenital varicella syndrome: still a problem? Fetal Diagn Ther. 2009;25:224–229. doi: 10.1159/000220602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer J, Whitley R. Varicella zoster virus: natural history and current therapies of varicella and herpes zoster. Herpes. 2007;14(Suppl 2):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WJ, Goodhouse J, Farquhar MG. Mannose-6-phosphate receptors for lysosomal enzymes cycle between the Golgi complex and endosomes. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1235–1247. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield WM, Johnson KF, Ye RD, Gregory W, Kornfeld S. Localization of the signal for rapid internalization of the bovine cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor to amino acids 24–29 of the cytoplasmic tail. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5682–5688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JE, Henderson EP, Grose C. Enumeration of an extremely high particle-to-PFU ratio for varicella-zoster virus. J Virol. 2009;83:6917–6921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Gershon A, Silverstein SJ, Li ZS, Lungu O, Gershon MD. Latent and lytic infection of isolated guinea pig enteric and dorsal root ganglia by varicella zoster virus. J Med Virol. 2003;70:S71–S78. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Zhu Z, Gershon AA, Gershon MD. Mannose 6-phosphate receptor dependence of varicella zoster virus infection in vitro and in the epidermis during varicella and zoster. Cell. 2004;119:915–926. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Gershon MD, Wan S, Cowles RA, Ruiz-Elizalde A, Bischoff S, Gershon AA. Latent infection of the human enteric nervous system by varicella zoster virus (VZV) Gastroenterology. 2009;136:W1689. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JI, Krogmann T, Pesnicak L, Ali MA. Absence or overexpression of the varicellazoster virus (VZV) ORF29 latency-associated protein impairs late gene expression and reduces VZV latency in a rodent model. J Virol. 2007;81:1586–1591. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01220-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs RJ, Gilden DH. Varicella zoster virus transcription in latently-infected human ganglia. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2063–2069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs RJ, Barbour MB, Mahalingam R, Wellish M, Gilden DH. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) transcription during latency in human ganglia: prevalence of VZV gene 21 transcripts in latently infected human ganglia. J Virol. 1995;69:2674–2678. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2674-2678.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs RJ, Barbour M, Gilden DH. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) transcription during latency in human ganglia: detection of transcripts to genes 21, 29, 62, and 63 in a cDNA library enriched for VZV RNA. J Virol. 1996;70:2789–2796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2789-2796.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs RJ, Gilden DH, Kinchington PR, Grinfeld E, Kennedy PG. Varicella-zoster virus gene 66 transcription and translation in latently infected human ganglia. J Virol. 2003;77:6660–6665. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6660-6665.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croen KD, Ostrove JM, Dragovic LY, Straus SE. Patterns of gene expression and sites of latency in human ganglia are different for varicella-zoster and herpes simplex viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9773–9777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach RJ, Miranda-Saksena M, Douglas MW, Cunningham AL. Transport and egress of herpes simplex virus in neurons. Rev Med Virol. 2008;18:35–51. doi: 10.1002/rmv.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JR, Kornfeld S. Intracellular movement of two mannose 6-phosphate receptors: return to the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:617–628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, Gnann JW, Levin MJ, Backonja M, Betts RF, Gershon AA, Haanpaa ML, McKendrick MW, Nurmikko TJ, Oaklander AL, Oxman MN, Pavan-Langston D, Petersen KL, Rowbotham MC, Schmader KE, Stacey BR, Tyring SK, van Wijck AJ, Wallace MS, Wassilew SW, Whitley RJ. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 1):S1–S26. doi: 10.1086/510206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller L, Jadwat Y, Bouckaert M. Herpes zoster post-herpetic neuralgia. S Afr Dent J. 2005;60(432):436–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Rowbotham M, Baron R. Postherpetic neuralgia: irritable nociceptors and deafferentation. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:209–227. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel CA, Foster SA. Mannose 6-phosphate receptor-mediated endocytosis of acid hydrolases: internalization of beta-glucuronidase is accompanied by a limited dephosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1817–1827. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.5.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel C, Dubey L, Steinberg S, Gershon M, Gershon A. Varicella-zoster virus glycoproteins are phosphorylated during posttranslational maturation. J Virol. 1989;63:4264–4276. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4264-4276.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon MD. Nerves, reflexes, and the enteric nervous system: pathogenesis of the irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S184–S193. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000156403.37240.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon MD, Rothman TP. Enteric glia. Glia. 1991;4:195–204. doi: 10.1002/glia.440040211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon AA, Sherman DL, Zhu Z, Gabel CA, Ambron RT, Gershon MD. Intracellular transport of newly synthesized varicella-zoster virus: final envelopment in the trans-Golgi network. J Virol. 1994;68:6372–6390. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6372-6390.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon A, Chen J, LaRussa P, Steinberg S. Varicella-zoster virus. In: Murray PR, Baron E, Jorgensen J, Landry M, Pfaller M, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 9th. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2007. pp. 1537–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon A, Takahashi M, Seward J. Live attenuated varicella vaccine. In: Plotkin S, Orenstein W, Offit P, editors. Vaccines. 5th. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2008a. pp. 915–958. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon AA, Chen J, Gershon MD. A model of lytic, latent, and reactivating varicellazoster virus infections in isolated enteric neurons. J Infect Dis. 2008b;197(Suppl 2):S61–S65. doi: 10.1086/522149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon AA, Chen J, Davis L, Krinsky C, Cowles R, Gershon MD. Presented at the 34th international herpesvirus workshop. Ithaca, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Goda Y, Pfeffer SR. Selective recycling of the mannose 6-phosphate/IGF-II receptor to the trans Golgi network in vitro. Cell. 1988;55:309–320. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold E. Serologic and virus-isolation studies of patients with varicella or herpes zoster infection. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:181–185. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196601272740403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowrishankar K, Slobedman B, Cunningham AL, Miranda-Saksena M, Boadle RA, Abendroth A. Productive varicella-zoster virus infection of cultured intact human ganglia. J Virol. 2007;81:6752–6756. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02793-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorakos L, Myrianthefs P, Markou N, Chroni D, Sakagianni E. Severity of illness and outcome in adult patients with primary varicella pneumonia. Respiration. 2002;69:330–334. doi: 10.1159/000063274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinfeld E, Kennedy PG. Translation of varicella-zoster virus genes during human ganglionic latency. Virus Genes. 2004;29:317–319. doi: 10.1007/s11262-004-7434-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinfeld E, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Kennedy PG. Varicella-zoster virus proteins encoded by open reading frames 14 and 67 are both dispensable for the establishment of latency in a rat model. Virology. 2004;323:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton S, Steinberg SP, Gershon MD, Gershon AA. Cholesterol dependence of varicella-zoster virion entry into target cells. J Virol. 2007;81:7548–7558. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00486-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head H, Campbell AW. The pathology of herpes zoster and its bearing on sensory localization. Brain. 1900;23:353–523. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(199709)7:3<131::aid-rmv198>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CF, Chan W, Kornfeld S. Cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor contains two internalization signals in its cytoplasmic domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:10010–10014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.10010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy PGE, Grinfeld E, Bell JE. Varicella-zoster virus gene expression in latently infected and explanted human ganglia. J Virol. 2000;74:11893–11898. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11893-11898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy PG, Grinfeld E, Bontems S, Sadzot-Delvaux C. Varicella-Zoster virus gene expression in latently infected rat dorsal root ganglia. Virology. 2001;289:218–223. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinchington PR, Bookey D, Turse SE. The transcriptional regulatory proteins encoded by varicella-zoster virus are open reading frames (ORFs) 4 and 63, but not ORF 61, are associated with purified virus particles. J Virol. 1995;69:4274–4282. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4274-4282.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld S. Trafficking of lysosomal enzymes. FASEB J. 1987;1:462–468. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.1.6.3315809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koropchak C, Solem S, Diaz P, Arvin A. Investigation of varicella-zoster virus infection of lymphocytes by in situ hybridization. J Virol. 1989;63:2392–2395. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2392-2395.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster MI. Making an epidermis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku CC, Padilla JA, Grose C, Butcher EC, Arvin AM. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human tonsillar CD4(+) T lymphocytes that express activation, memory, and skin homing markers. J Virol. 2002;76:11425–11433. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11425-11433.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku CC, Zerboni L, Ito H, Graham BS, Wallace M, Arvin AM. Varicella-zoster virus transfer to skin by T cells and modulation of viral replication by epidermal cell interferon-{alpha} J Exp Med. 2004;200:917–925. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Ali MA, Cohen JI. Insulin degrading enzyme is a cellular receptor mediating varicella-zoster virus infection and cell-to-cell spread. Cell. 2006;127:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry PW, Solem S, Watson BN, Koropchak C, Thackeray H, Kinchington P, Ruyechan W, Ling P, Hay J, Arvin A. Immunity in strain 2 guinea pigs inoculated with vaccinia virus recombinants expressing varicella-zoster virus glycoproteins I, IV, V, or the protein product of the immediate early gene 62. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:811–819. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-4-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry PW, Sabella C, Koropchek C, Watson BN, Thackray HM, Abruzzi GM, Arvin AM. Investigation of the pathogenesis of varicella-zoster virus infection in guinea pigs by using polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:78–83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lungu O, Annunziato P, Gershon A, Stegatis S, Josefson D, LaRussa P, Silverstein S. Reactivated and latent varicella-zoster virus in human dorsal root ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10980–10984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lungu O, Panagiotidis C, Annunziato P, Gershon A, Silverstein S. Aberrant intracellular localization of varicella-zoster virus regulatory proteins during latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7080–7085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunga Y, Yamanishi K, Takahashi M. Experimental infection and immune responses of guinea pigs with varicella zoster virus. Infect Immun. 1982;37:407. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.407-412.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, Stocks EA, Hauer P, Cornblath DR, Griffin JW. Epidermal nerve fiber density: normative reference range and diagnostic efficiency. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1513–1520. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat JF, Stein MD, Kaneshima H, Arvin AM. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and epidermal cells in SCID-hu mice. J Virol. 1995;69:5236–5242. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5236-5242.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska L. Droplet fate in indoor environments, or can we prevent the spread of infection? Indoor Air. 2006;16:335–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriuchi H, Moriuchi M, Straus S, Cohen J. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) open reading frame 61 protein transactivates VZV gene promoters and enhances the infectivity of VZV DNA. J Virol. 1993;67:4290–4295. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4290-4295.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller NH, Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA. Varicella zoster virus infection: clinical features, molecular pathogenesis of disease, and latency. Neurol Clin. 2008;26:675–697. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen K, Mustakangas P, Valanne L, Professor MH, Koskiniemi M. Congenital varicella-zoster virus infection after maternal subclinical infection: clinical and neuropathological findings. J Perinatol. 2001;21:141–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M, Duer HL, Haulser CK. Experimental infection of guinea pigs with varicella-zoster virus. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:414–420. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M, Stanberry L, Edmond B. Varicella-zoster virus infection of strain 2 guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:106–113. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Connelly B, Stanberry LR. Varicella in hairless guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:746–751. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima K, Nakazawa M, Endo H. Pathology of the human spinal ganglia in varicella-zoster virus infection. Acta Neuropathol. 1975;33:105–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00687537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel MA, Gilden DH. The protean neurologic manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:489–494. 496, 498–499. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.74.7.489. passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proksch E, Brandner JM, Jensen JM. The skin: an indispensable barrier. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:1063–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt M, Brady J, Arvin AM. The replication cycle of varicella-zoster virus: analysis of the kinetics of viral protein expression, genome synthesis, and virion assembly at the single-cell level. J Virol. 2009;83:3904–3918. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02137-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentier B, Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Nikkels A, Piette J, Mahalingam R, Wellish M, Cohrs R, Gilden DH, Lungu O, LaRussa P, Silverstein S, Annunziato P, Gershon A. Presented at the keystone symposium on virus entry, replication, and pathogenesis. Santa Fe, NM: 1996. pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ross AH, Lencher E, Reitman G. Modification of chickenpox in family contacts by administration of gamma globulin. N Engl J Med. 1962;267:369–376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196208232670801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Pesnicak L, Cohen JI. Use of a rodent model to show that varicella-zoster virus ORF61 is dispensable for establishment of latency. J Med Virol. 2003;70(Suppl 1):S79–S81. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P. The congenital varicella syndrome. J Perinatol. 2000;20:548–554. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer M, Chamberlin C, Wu Y, Aintablian N, Wallace M. Detection of varicella-zoster virus DNA in air samples from hospital rooms. J Infect Dis. 1993;169:91–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaap A, Fortin JF, Sommer M, Zerboni L, Stamatis S, Ku CC, Nolan GP, Arvin AM. T-cell tropism and the role of ORF66 protein in pathogenesis of varicella-zoster virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:12921–12933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12921-12933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrar RG, LaRussa P, Galea S, Steinberg S, Sweet A, Keatley M, Wells M, Stephenson W, Gershon A. The postmarketing safety profile of varicella vaccine. Vaccine. 2000;19:916–923. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong W, Schultz JC, Patera AC, Sommer MH, Cohen JI. Infection of human T lymphocytes with varicella-zoster virus: an analysis with viral mutants and clinical isolates. J Virol. 2000;74:1864–1870. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1864-1870.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsolia M, Gershon A, Steinberg S, Gelb L. Live attenuated varicella vaccine: evidence that the virus is attenuated and the importance of skin lesions in transmission of varicella-zoster virus. J Pediatr. 1990;116:184–189. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82872-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MR, Bowler WA, Oldfield EC., 3rd Treatment of varicella in the immunocompetent adult. J Med Virol. 1993;(Suppl 1):90–92. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Sommer M, Rajamani J, Arvin AM. Regulation of the ORF61 promoter and ORF61 functions in varicella-zoster virus replication and pathogenesis. J Virol. 2009;83:7560–7572. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00118-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZH, Gershon MD, Lungu O, Zhu Z, Mallory S, Arvin A, Gershon A. Essential role played by the C-terminal domain of glycoprotein I in envelopment of varicella-zoster virus in the trans-Golgi network: interactions of glycoproteins with tegument. J Virol. 2001;75:323–340. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.323-340.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SM, Shah SS, Steenhoff AP, Rutstein RM. Primary varicella and herpes zoster among HIV-infected children from 1989 to 2006. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e150–e156. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadavalli S, Nadimpalli SK. Role of cation independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor protein in sorting and intracellular trafficking of lysosomal enzymes in chicken embryonic fibroblast (CEF) cells. Glycoconj J. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10719-009-9267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa T, Ihira M, Suzuki K, Suga S, Tomitaka A, Ueda H, Asano Y. Rapid contamination of the environment with varicella-zoster virus DNA from a patient with herpes zoster. J Med Virol. 2001;63:64–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu IT, Li Y, Wong TW, Tam W, Chan AT, Lee JH, Leung DY, Ho T. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1731–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerboni L, Ku CC, Jones CD, Zehnder JL, Arvin AM. Varicella-zoster virus infection of human dorsal root ganglia in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6490–6495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501045102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Gershon MD, Gabel C, Sherman D, Ambron R, Gershon AA. Entry and egress of VZV: role of mannose 6-phosphate, heparan sulfate proteoglycan, and signal sequences in targeting virions and viral glycoproteins. Neurology. 1995;45:S15–S17. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.12_suppl_8.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]