Abstract

We test the relation between ambiguity aversion and five household portfolio choice puzzles: nonparticipation in equities, low allocations to equity, home-bias, own-company stock ownership, and portfolio under-diversification. In a representative US household survey, we measure ambiguity preferences using custom-designed questions based on Ellsberg urns. As theory predicts, ambiguity aversion is negatively associated with stock market participation, the fraction of financial assets in stocks, and foreign stock ownership, but it is positively related to own-company stock ownership. Conditional on stock ownership, ambiguity aversion is related to portfolio under-diversification, and during the financial crisis, ambiguity-averse respondents were more likely to sell stocks.

Keywords: ambiguity aversion, stock market participation, household portfolio puzzles, home-bias, own-company stock puzzle, portfolio under-diversification, household finance, financial literacy

1. Introduction

Households must consider both risk and ambiguity when making investment decisions. Risk refers to events for which the probabilities of the future outcomes are known. Ambiguity refers to events for which the probabilities of the future outcomes are unknown. Ellsberg (1961) argues that most people are ambiguity-averse, that is, they prefer a lottery with known probabilities to a similar lottery with unknown probabilities, and numerous theoretical studies explore the implications of ambiguity for economic behavior. A large body of theory suggests that ambiguity aversion can explain several household portfolio choice puzzles.1 Empirical tests for some of these theoretical explanations, however, derive mainly from laboratory experiments instead of actual portfolio choices. In other cases, the proposed theoretical explanations have not been empirically tested.

In this paper, we provide non-laboratory empirical evidence that ambiguity aversion relates to five household portfolio choice puzzles: nonparticipation in equity markets, low portfolio fractions allocated to equity, home-bias, own-company stock ownership, and portfolio under-diversification. In a nationally representative sample of US households, we use real rewards to elicit measures of individuals’ ambiguity aversion and then demonstrate that these measures can explain actual portfolio choices. As theory predicts, ambiguity aversion is negatively associated with stock market participation, the fraction of financial assets allocated to stocks, and foreign stock ownership, but ambiguity aversion is positively related to own–company stock ownership. Conditional on stock ownership, ambiguity aversion also helps to explain portfolio under-diversification.

We have developed a purpose-built internet survey module designed to elicit ambiguity aversion and fielded it on more than three thousand respondents in the American Life Panel (ALP). Following the classic Ellsberg urn problem, our module asks respondents to choose between a lottery with known probabilities (the drawing of a ball from a box with one hundred colored balls in known proportions) versus a lottery with unknown probabilities. We vary the proportions of colored balls in the lottery with known probabilities, so as to measure individual respondents’ ambiguity aversion. All respondents were eligible to win real monetary incentives (we paid a total of $23,850 to 1,590 of the 3,258 respondents), because previous studies show that rewards are crucial for eliciting meaningful responses to questions involving economic preferences.

Our results confirm prior laboratory studies finding large heterogeneity in ambiguity aversion; that is, a substantial fraction of our respondents is ambiguity-averse (52%); a small fraction ambiguity-neutral (10%); and the remainder ambiguity-seeking (38%). We find little to no correlation between our ambiguity measure and several proxies for probability naiveté, thereby providing evidence that our measure reflects preferences, not mistakes. Having elicited ambiguity aversion, we then test whether it can help explain household portfolio choice puzzles.

A large proportion of the US population does not participate in the stock market, which is puzzling given that theoretical models using standard expected utility functions predict that all individuals will do so (Merton, 1969). For those who do participate, theory predicts they will allocate a counterfactually high fraction of assets to equity (Heaton and Lucas, 1997). Several theoretical papers suggest that ambiguity aversion can explain these puzzles, based on the assumption that investors view stock returns as ambiguous. Bossaerts, Ghirardato, Guarnaschelli, and Zame (2010), Cao, Wang, and Zhang (2005), Dow and Werlang (1992), Easley and O’Hara (2009), and Epstein and Schneider (2010), among others, show that ambiguity aversion can cause nonparticipation.2 Garlappi, Uppal, and Wang (2007) and Peijnenburg (2014) show that ambiguity aversion can reduce the fraction of financial assets allocated to equity.

We test the predictions of these theoretical models and find that ambiguity aversion has a significant negative relation with both stock market participation and portfolio allocations to equity. Results indicate that a one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion implies a 2.0 percentage point decrease in the probability of stock market participation (8.6% relative to the baseline rate of 23%) and a 4.0 percentage point decrease in the fraction of financial assets allocated to equity (7.8% relative to the conditional average allocation of 51.4%). The results are robust to controlling for numerous variables that previous studies suggest could affect household portfolio choices, including wealth, income, age, education, risk aversion, trust, and financial literacy. The module also includes two check questions to assess whether a respondent’s choices are consistent. We find stronger results for respondents whose choices are consistent.

In addition to explaining participation in and allocations to equities as a broad asset class, theory suggests that ambiguity aversion can help explain portfolio puzzles related to particular categories of equity: the home-bias and own-company stock puzzles. The home-bias puzzle refers to the fact that households heavily overweight domestic equity relative to mean-variance benchmarks (French and Poterba, 1991). The own-company stock puzzle refers to the fact that households voluntarily hold significant amounts of their employers’ stock (Benartzi, 2001; Meulbrook, 2005; Mitchell and Utkus, 2003). Several theoretical papers argue that ambiguity aversion can explain these puzzles, because, relative to the domestic stock market, foreign stocks are relatively ambiguous and own-company stock is relatively unambiguous (e.g., Boyle, Uppal, and Wang, 2003; Boyle, Garlappi, Uppal, and Wang, 2012; Cao, Han, Hirshleifer, and Zhang, 2011; Epstein and Miao, 2003; Uppal and Wang, 2003). Thus, the portfolio of an ambiguity-averse investor is biased away from foreign stocks but toward own-company stock. To our knowledge, we are the first to empirically test these predictions.

We find evidence consistent with both predictions. Ambiguity aversion is negatively related to foreign stock ownership, but positively related to own-company stock ownership. This pattern holds both in the overall sample and within the subset of equity holders. The results for equity owners are of particular interest, as they demonstrate that ambiguity aversion helps to explain the composition of equity portfolios and not only the participation decision. Our results also provide evidence that ambiguity aversion is not simply a proxy for risk aversion, because, for foreign and own-company stock ownership, the theoretical effect of risk aversion is exactly opposite to that of ambiguity aversion.

The paper also tests the Heath and Tversky (1991) competence hypothesis, which predicts that the effect of ambiguity aversion depends on individuals’ domain-specific knowledge. Although people are generally ambiguity-averse toward tasks for which they do not feel competent (e.g., guessing the composition of an Ellsberg urn), they are much less ambiguity-averse toward tasks for which they believe they have expertise. Hence, we expect that higher stock market competence will moderate the relation between a respondent’s ambiguity aversion toward Ellsberg urns and his ambiguity aversion toward stock investments. We measure stock market competence in two ways: self-assessed stock market knowledge and financial literacy. For both measures, we find that the negative effect of ambiguity aversion on stock market participation is stronger for people with lower stock market competence, consistent with the implications of the competence hypothesis.

Furthermore, theory suggests that ambiguity aversion relates to portfolio under–diversification, with the effect of ambiguity aversion depending on the relative ambiguity of the overall market compared with individual stocks. Boyle, Garlappi, Uppal, and Wang (2012) find that an agent who views the overall stock market as highly ambiguous, relative to some limited number of familiar individual stocks, will invest in the individual stocks, thereby holding an under-diversified portfolio. Consistent with this hypothesis, we find that, conditional on participation, the fraction of the portfolio allocated to individual stocks is increasing in ambiguity aversion for individuals with low self-assessed knowledge about the overall stock market. These individuals view the overall stock market as highly ambiguous and so conditional on participation, they hold only a few individual stocks.

In most models of ambiguity, the effect of ambiguity aversion is stronger when the perceived level of ambiguity is high. We therefore also test how equity owners reacted to the 2008–2009 financial crisis, a period when the perceived ambiguity of future asset returns increased sharply (e.g., Bernanke, 2010; Caballero and Simsek, 2013). Our results show that respondents with higher ambiguity aversion were significantly more likely to actively sell equities during the crisis. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical test examining how ambiguity aversion affects active changes in household portfolios during times of market turmoil.

To explore the implied magnitude of our findings on asset prices, we calibrate the general equilibrium asset pricing model by Bossaerts, Ghirardato, Guarnaschelli, and Zame (2010) using our survey estimates. Although we find that ambiguity preferences lead to a higher equity premium, our estimates suggest that heterogeneity mitigates the effect of ambiguity aversion on asset prices, as ambiguity-averse and -seeking agents have opposite demands for securities with uncertain payoffs.

This paper contributes to the literature by testing theoretical models that use ambiguity aversion to explain household portfolio choice. Aside from a few laboratory experiments (e.g., Bossaerts, Ghirardato, Guarnaschelli, and Zame, 2010), we are the first to show a significant relation between ambiguity aversion and stock market participation. Dimmock, Kouwenberg, and Wakker (2015) develop and apply a method for eliciting ambiguity attitudes in a Dutch household survey. Their primary focus is to develop the elicitation method, but they also examine whether ambiguity aversion is related to stock market participation. In their relatively small data set, they found no significant relation except for a subset of respondents having low perceived knowledge about future asset returns. Because this is not their main focus, and because their data set does not contain the necessary variables, they do not test any other hypotheses related to household portfolio choice. Further, their measures of ambiguity attitudes are based on a particular model of ambiguity, the source method of Abdellaoui, Baillon, Placido, and Wakker (2011) and Chew and Sagi (2008), which differs from the models of ambiguity used in the finance literature. Accordingly, the tests in Dimmock, Kouwenberg, and Wakker (2015) do not align with the theoretical predictions in the literature. By contrast, in the present study, our measure of ambiguity aversion is consistent with the underlying models of preferences used in the finance literature.

Our data set contains detailed information about household portfolios, allowing us to test a rich set of hypotheses. Our paper is the first non-laboratory analysis to show that ambiguity aversion can help explain five household choice puzzles: equity nonparticipation, the low fraction of assets allocated to equities, home-bias, own-company stock investment, and portfolio under-diversification. We are also the first to show that ambiguity aversion relates to active portfolio changes in response to the financial crisis. Our results are consistent with the predictions of a large number of theoretical models, and we show that ambiguity aversion can help explain numerous puzzling features of households’ portfolio choices.

In what follows, Section 2 describes how we measure ambiguity aversion in an online survey in which we paid subjects real rewards based on their choices. Our survey results are discussed in Section 3. The next two sections explore the relationship between ambiguity aversion, stock holding, home-bias, and own-company stock ownership. In Section 6, we examine how ambiguity aversion depends on investors’ familiarity (or competence) with the stock market, and how it influences their portfolio diversification. Section 7 outlines the interaction between investor ambiguity aversion and behavior during the 2008–2009 financial crisis. In Section 8 we discuss asset pricing implications. A final section concludes.

2. Measuring ambiguity aversion

To elicit ambiguity aversion we designed a special module for the ALP survey (see Online Appendix A). Our questions are posed as choices between an ambiguous Box U (unknown) and an unambiguous Box K (known), similar to the famous Ellsberg (1961) two urn experiment.3 As shown in Fig. 1, both boxes contain exactly one hundred balls, which can be purple or orange. The respondent selects one of the boxes, and then a ball is randomly drawn from that box. He wins $15 if that ball is purple and $0 if the ball is orange. For Box K, the number of purple balls is explicitly stated (50), as well as the number of orange balls (50). For Box U, the number of purple balls is not given, and the respondent only knows it is between zero and one hundred. A respondent who prefers Box K over Box U is ambiguity-averse; that is, he prefers known probabilities to unknown probabilities.4 In the survey, a respondent can also choose “Indifferent” instead of Box K or Box U. A choice of “Indifferent” implies that the respondent considers Box K and Box U equally attractive, and so he is ambiguity-neutral. An ambiguity-neutral subject treats the subjective probability of winning for Box U as if it were equal to the 50% known probability of winning for Box K. For this reason, we refer to 50% as Box U’s ambiguity-neutral probability of winning.

Fig. 1.

Choosing between two boxes with purple and orange balls, one having a known (50%) chance of winning and the other ambiguous. This figure shows a screen shot from our American Life Panel module representing the first question in the ambiguity elicitation sequence. Box K has a 50% initial known probability of winning; Box U has an unknown mix of purple and orange balls. If the respondent selects “Box K,” he is taken to a new question with a lower probability of winning in Box K (fewer purple balls). If he selects “Box U,” the next question has a higher winning probability of winning in Box K (more purple balls). If the respondent selects “Indifferent,” or after four rounds, the question sequence is complete.

To more precisely measure respondents’ ambiguity aversion, we follow an approach similar to that of Baillon and Bleichrodt (2015), Baillon, Cabantous, and Wakker (2012), and Dimmock, Kouwenberg, and Wakker (2015). Our question sequence takes the respondent through a series of choices that are conditional on prior answers and converge toward the point of indifference. For example, suppose a respondent displays ambiguity aversion in the first round of the question, preferring Box K over Box U (see Fig. 1). We then decrease Box K’s known probability of winning to 25% in the second round (see Fig. A2 in Online Appendix A). Alternatively, if the respondent chooses Box U in the first round, we then increase the known probability of winning to 75%. This process is repeated for up to four rounds, until the respondent’s indifference point is closely approximated.5 We refer to the known probability of winning for Box K at which the respondent is indifferent between Box K and Box U as the matching probability (Wakker, 2010). For example, a matching probability of 40% means the respondent is indifferent between drawing a purple ball from Box K with a known probability of winning equal to 40% versus drawing a purple ball from Box U with an unknown probability.

A key appeal of this approach is that matching probabilities measure ambiguity aversion relative to risk aversion, because the alternative to the ambiguous choice is a risky choice, not a certain outcome. As a result, all other features of utility such as risk aversion or probability weighting are differenced out of the comparison, as risk aversion has an identical effect on the evaluation of the risky lottery and on the ambiguous lottery. For example, different subjects can receive different utilities from a prize of $15. But our matching probabilities measure a within-subject comparison between a risky lottery and an ambiguous lottery and, because the prize is the same for both boxes, the utility of $15 is differenced out of the comparison. Accordingly, cross-subject differences in utility are irrelevant. Matching probabilities capture only differential preferences for ambiguity relative to risk.6

Because the ambiguity-neutral probability of the ambiguous lottery is 50%, a respondent with a matching probability below 50% is ambiguity-averse. A respondent with a matching probability equal to 50% is ambiguity-neutral, and a respondent with a matching probability above 50% is ambiguity-seeking. In what follows, q denotes the matching probability and we define our key measure as Ambiguity Aversion = 50% − q. Thus, positive values of this measure indicate ambiguity aversion, zero indicates ambiguity neutrality, and negative values indicate ambiguity-seeking. In some of the empirical tests, we use two additional measures of ambiguity aversion. The first is simply an indicator variable equal to one if the respondent shows ambiguity aversion for the first round of the question (i.e., if he selects Box K in the first round). The second is the rank transformation of the Ambiguity Aversion measure, with zero indicating the lowest level of ambiguity aversion and one the highest.

Importantly, subjects could win real rewards based on their choices, because prior studies show that offering such rewards produces more reliable estimates of preferences (Smith, 1976). The instructions at the start of the survey told the subjects that one of their choices would be randomly selected and played for a chance to win $15. We paid a total of $23,850 in real incentives to 1,590 of the 3,258 ALP subjects. The RAND Corporation’s ALP was responsible for determining the incentives won by respondents and making payments. Accordingly, suspicion about the trustworthiness of the incentive scheme should play no role, as subjects regularly participate in ALP surveys and receive incentive payments from RAND.

In Ellsberg experiments, respondents can usually choose the winning color, to rule out potential suspicion that the ambiguous urn is manipulated to contain fewer purple balls than orange balls. In our survey, we elected not to add an option to change the winning color, as we sought to keep the survey as simple as possible for use in the general population. Further, the survey was administered by RAND Corporation’s ALP, which should minimize distrust. Prior studies have also demonstrated overwhelmingly that subjects are indifferent between betting on either color (e.g., Abdellaoui, Baillon, Placido, and Wakker, 2011; Fox and Tversky, 1998). To confirm this, we gave a separate group of 250 respondents the option to select the winning color and found no significant differences in ambiguity aversion from the main survey sample.7

Because elicited preferences likely contain measurement error (see Harless and Camerer, 1994; Hey and Orme, 1994), we also included two check questions to test the consistency of subjects’ choices. After each subject completed the ambiguity questions, we estimated his matching probability, q. We then generated two check questions by changing the known probability of winning for Box K to q + 10% in the first question and q − 10% in the second. Box U remained unchanged. A subject’s response is deemed inconsistent if he preferred the ambiguous Box U in the first check question or the unambiguous Box K in the second check question. Online Appendix A details the elicitation procedure including the consistency checks.

3. Data and variables

Our survey module to measure ambiguity aversion was implemented in the RAND American Life Panel.8 The ALP consists of several thousand households that regularly answer Internet surveys. Households lacking Internet access at the recruiting stage were provided with a laptop and wireless service to limit selection biases. To ensure that the sample is representative of the US population, we use survey weights provided by the ALP for all analyses and summary statistics reported in this paper. Our ambiguity survey was fielded in mid-March of 2012, and the survey was closed in mid-April 2012. In addition to the ambiguity aversion variables derived from our module, we use variables derived from other ALP surveys. Many of these are taken from the core ALP modules administered to respondents when they enter the ALP or shortly thereafter. Furthermore, we use several variables from modules developed by other researchers that were fielded between 2008 and 2014. No specific subset of respondents is excluded in any of these modules and, after a certain period of time, the survey was closed. Table 1 defines all our variables, and Table 2 provides summary statistics. The last column of Table 2 indicates the number of valid responses for each variable.

Table 1.

Variables in the American Life Panel Survey module

| Variable name | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stock Ownership | Indicator that respondent holds equities in his personal portfolio (stocks or stock mutual funds) |

| Fraction Allocated to Stocks | Equity holdings as a % of financial assets (checking, saving, money market, bonds, CDs, mutual funds, and stocks) |

| Foreign Stock Ownership | Indicator that respondent holds foreign stocks in his personal portfolio |

| Own-Company Stock Ownership | Indicator that respondent holds his employer’s stocks in his personal portfolio |

| Individual Stock Ownership | Indicator that respondent holds individual stocks in his personal portfolio |

| Fraction of Equity Allocated to Individual Stocks | Individual stock holdings as a % of assets invested in stocks |

| Stock Sales during Crisis | Indicator if respondent actively sold stocks during financial crisis |

| Age | Age in years |

| Male | Indicator for male |

| White | Indicator if respondent considers himself primarily White |

| Hispanic | Indicator if respondent considers himself primarily Hispanic |

| Married | Indicator if respondent is married or has a partner |

| Number of Children | Number of living children |

| Health | Self-reported health status ranging from 0 (“Poor”) – 4 (“Excellent”) |

| LT High School | Indicator if respondent had less than a high school degree |

| High School Graduate | Indicator if respondent completed high school but not college |

| College+ | Indicator if respondent completed college |

| Employed | Indicator if respondent is employed |

| Family Income | Total income for all household members older than 15, including from jobs, business, farm, rental, pension benefits, dividends, interest, social security, and other income |

| Wealth | The sum of net financial wealth, net housing assets, and imputed social security wealth using respondent self-reported claim ages, actual or estimated monthly benefits, and cohort life tables |

| Defined Contribution | Indicator if respondent has a defined contribution pension plan |

| Defined Benefit | Indicator if respondent has a defined benefit pension plan |

| Financial Literacy | Number of financial literacy questions answered correctly (out of 3 total; see Online Appendix C) |

| Trust | Ranges from 0 to 5; 0 corresponds to “most people can be trusted” and 5 corresponds to “you can’t be too careful” |

| Risk Aversion | Estimated coefficient of risk aversion based on lottery questions, > 0 if risk averse, = 0 if risk neutral, < 0 if risk seeking |

| Question Order | Indicator if subject answered the risk aversion question before the ambiguity questions (the question order was randomized) |

Table 2. Summary statistics for outcome and control variables.

This table reports summary statistics for the variables used in our study. Variable definitions appear in Table 1. The summary statistics for Fraction Allocated to Stocks are shown for all respondents and for the subsample of respondents with a nonzero allocation to equity. From the original sample of 3,258 American Life Panel (ALP) respondents, we omit 188 people who spent less than two minutes on the ambiguity questions, resulting in a sample size of 3,070 subjects. For several variables in Table 2, there are missing observations. The last column shows the number of non-missing observations for each variable (N). All results use ALP survey weights.

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Median | Maximum | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stock Ownership (percent) | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,025 |

| Fraction Allocated to Stocks (percent) | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,025 |

| Foreign Stock Ownership (percent) | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 799 |

| Own-Company Stock Ownership (percent) | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 670 |

| Individual Stock Ownership (percent) | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2,757 |

| Fraction Allocated to Individual Stocks Conditional (percent) | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.24 | 1 | 321 |

| Stock Sales during the Financial Crisis (percent) | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 528 |

| Age | 46.38 | 15.20 | 18 | 48 | 70 | 3,070 |

| Male (percent) | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,070 |

| White (percent) | 0.81 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3,066 |

| Hispanic (percent) | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,069 |

| Married (percent) | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2,695 |

| Number of Children | 1.67 | 1.62 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 3,024 |

| Health | 2.48 | 0.93 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 2,969 |

| LT High School (percent) | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,069 |

| High School (percent) | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,069 |

| College+ (percent) | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3,069 |

| Employed (percent) | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,068 |

| Family Income ($) | 69,295 | 69,774 | 2,500 | 55,000 | 400,000 | 3,061 |

| Wealth ($) | 317,076 | 584,485 | −88,743 | 112,928 | 4,188,110 | 2,969 |

| Defined Contribution | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2,991 |

| Defined Benefit | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2,991 |

| Financial Literacy | 2.18 | 0.93 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3,070 |

| Trust | 3.20 | 1.41 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3,035 |

| Risk Aversion | 0.34 | 0.45 | −0.50 | 0.41 | 0.98 | 3,036 |

| Question Order | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3,070 |

The first seven rows of Table 2 summarize our key dependent variables. These financial variables were measured in different ALP survey modules, many of which included only a subset of the ALP participants. The sample sizes of the dependent variables differ depending on the number of people surveyed in the specific modules. We find no significant correlations between ambiguity aversion and inclusion in these modules, suggesting that sample selection bias is unlikely.

Stock Ownership is an indicator variable equal to one if the respondent holds stocks (either individual stocks or equity mutual funds) in his personal portfolio. The equity participation rate in our sample is 23%.9 The second row shows that the unconditional average fraction of financial assets allocated to stocks is 12%. Conditional on stock market participation, the average fraction is 51%. For the subsequent dependent variables, the sample sizes are lower because our survey module did not overlap perfectly with respondents to other modules. Foreign Stock Ownership is an indicator variable equal to one if the respondent owns foreign stocks or equity mutual funds. Thirteen percent of the sample own foreign stocks. Own-Company Stock Ownership is an indicator variable equal to one if the respondent owns shares in his current or previous employer (outside of his retirement account). Five percent of the sample has own-company stock. For own-company stock, we restrict the sample to employed respondents. Individual Stock Ownership is an indicator variable equal to one if the respondent owns individual shares (excluding own-company stock). Seventeen percent of the sample owns individual shares. Conditional on nonzero equity ownership, the average fraction allocated to individual stocks is 42%. For a subsample of the individual stock owners, we can observe the number of individual shares that they own. Consistent with other studies of household portfolios, we find that, conditional on owning individual stocks, the median number of individual companies held is two, which suggests that individual stock ownership is a reasonable proxy for under-diversification. The variable Stock Sales during the Financial Crisis is derived from a survey fielded in May 2009, and it is equal to one if the respondent actively sold stocks during the financial crisis, conditional on owning stocks before the crisis.10

In all empirical tests, we control for demographic and economic characteristics: age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, self-reported health status, education, employment status, family income and wealth, and retirement plan type. Controlling for these variables partials out the potential confounding effects that they could have on household portfolio choice, thus providing cleaner estimates of the effect of ambiguity aversion.

Our ALP survey module included additional questions to measure trust, financial literacy, and risk aversion. (Online Appendix B provides the exact wording of these questions and additional details.) We include these variables to avoid omitted variable biases, as these could affect portfolio choice and could measure something conceptually similar to ambiguity aversion. For example, ambiguity aversion could be influenced by trust (i.e., people who distrust others could assume that ambiguous events are systematically biased against them). For this reason, we follow Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales (2008) by adding the trust question from the World Values Survey.11

We also control for financial literacy, as prior studies show it has a strong relation with financial decisions (e.g., Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014; van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie, 2011). To ensure that ambiguity aversion is not simply a proxy for low financial literacy, our survey module included three questions akin to those devised by Lusardi and Mitchell (2007) for the Health and Retirement Study. Our index of financial literacy is the number of correct responses to these questions. Table 2 shows that, on average, respondents answer slightly more than two of the questions correctly.

Our methodology is designed to elicit ambiguity aversion in a manner unaffected by risk aversion. Nevertheless, we control for risk aversion for two reasons. First, we seek to ensure that our ambiguity aversion variable captures a distinct component of preferences, separate from risk aversion. Second, ambiguity aversion and risk aversion could be correlated, in which case ambiguity attitudes could provide little incremental information about preferences. To measure risk aversion, we modify the Tanaka, Camerer, and Nguyen (2010) method. Furthermore, we include financial wealth as a control variable, which is the strongest predictor of risk aversion in household data (Calvet and Sodini, 2014). As shown in Fig. 2, we ask the respondent to choose between a certain outcome and a risky outcome. Based on the response, the survey generates a new binary choice similar to the method for eliciting ambiguity aversion described previously. Table 2 shows that the average respondent is risk-averse, but there is substantial variation and some people are risk seeking. The order of the risk and ambiguity elicitation questions was randomized in the survey. In the regressions, we include a dummy for the question order as a control.

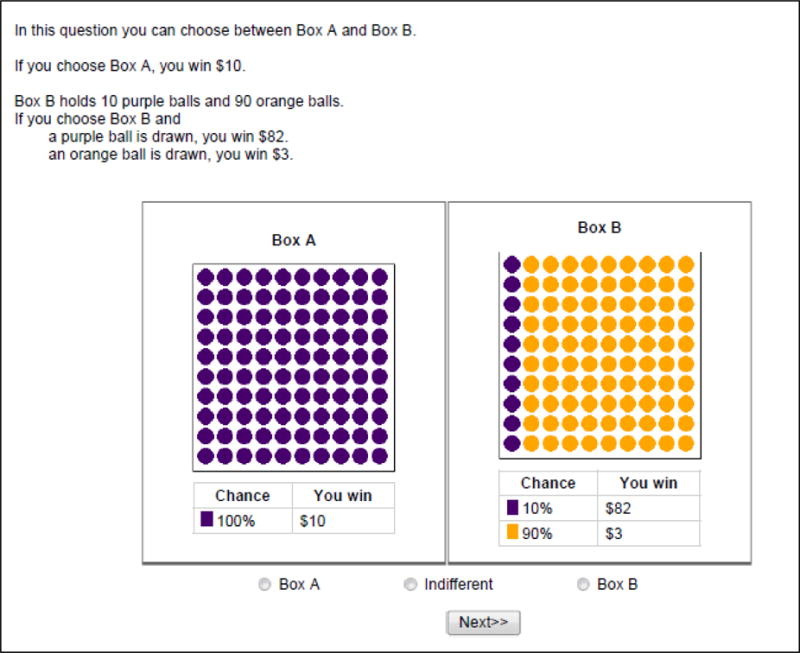

Fig. 2.

Choosing between two boxes with purple and orange balls, one having a sure (100%) chance of winning and the other having a risky but well-defined probability distribution of outcomes. This figure shows a screen shot from our American Life Panel module in the probability risk sequence. If the respondent chooses Box A, he wins with certainty; if he chooses Box B, winning is random. If he selects “Box A,” the respondent gets a new question with a higher probability of winning in Box B (more purple balls). If he selects “Box B,” the next question has a lower winning probability in Box B. If he selects “Indifferent,” the question sequence is complete.

Table 3 summarizes ambiguity aversion in the ALP sample. Panel A shows that 52% of the respondents are ambiguity-averse, 10% are ambiguity-neutral, and 38% are ambiguity-seeking. These results are roughly consistent with the findings from a targeted survey of Italian households by Butler, Guiso, and Jappelli (2014).12 They are also within the range of results from a large number of studies summarized by Oechssler and Roomets (2014) and Trautmann and van de Kuilen (2015). Panel B summarizes the key ambiguity aversion measure: on average, respondents are ambiguity-averse, but strong heterogeneity also exists in ambiguity preferences. This finding is of importance for the finance literature, as Bossaerts, Ghirardato, Guarnaschelli, and Zame (2010) show that heterogeneity in investors’ ambiguity aversion results in equilibrium asset prices that cannot be replicated by a standard representative agent model with one representative ambiguity-averse agent (we explore the asset pricing implications of our estimates in Section 8 and Online Appendix D).13 Panel C shows the results for the two check questions. The percentage of respondents giving inconsistent answers is 30.4 for the first question and 14.0 for the second. These rates are similar to those found in laboratory studies of preferences (e.g., Harless and Camerer, 1994). In all subsequent regressions, we include a dummy variable for whether the respondent made errors on the check questions as a control.

Table 3. Ambiguity aversion in the US population.

This table shows ambiguity aversion in the US population measured using our American Life Panel (ALP) survey module. Panel A shows the proportion of respondents who are ambiguity-averse, ambiguity-seeking, or ambiguity-neutral, as revealed by their first-round choice between Box K and Box U (see text and Fig. 1). Panel B summarizes the Ambiguity Aversion measure. We define Ambiguity Aversion = 50% − q where q denotes the matching probability for Box U in Fig. 1 (with two ball colors, in unknown proportions). Panel C summarizes the percentage of respondents who gave inconsistent answers to the two check questions. Panel D shows the pairwise correlations between ambiguity aversion and variables measuring education, financial literacy, self-assessed stock market knowledge, and making errors on the check questions. The sample size is N = 3,040. Of the initial 3,258 respondents in our ALP survey, 188 were eliminated because they took less than two minutes to answer the survey questions. Of the remaining 3,070 respondents, 30 did not complete the ambiguity questions. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

| Panel A: Proportion of respondents ambiguity-averse, -neutral, and -seeking | |||||

|

| |||||

| Measure | Percent | ||||

| Ambiguity-averse | 0.52 | ||||

| Ambiguity-neutral | 0.10 | ||||

| Ambiguity-seeking | 0.38 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Panel B: Summary statistics ambiguity aversion measure | |||||

|

| |||||

| Measure | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Median | Maximum |

| Ambiguity Aversion | 0.018 | 0.213 | −0.440 | 0.030 | 0.470 |

|

| |||||

| Panel C: Check question responses | |||||

|

| |||||

| Question | Not inconsistent | Inconsistent | |||

| Check question 1 | 69.6% | 30.4% | |||

| Check question 2 | 86.0% | 14.0% | |||

|

| |||||

| Panel D: Bivariate correlations with ambiguity aversion measure | |||||

|

| |||||

| Educational Level | Correlation | ||||

| High School Graduate | −0.05*** | ||||

| College+ | 0.07*** | ||||

| Financial Literacy | 0.04** | ||||

| Self-Assessed Stock Market Knowledge | 0.03 | ||||

| Errors on Check | −0.16*** | ||||

In an additional analysis of the demographics of ambiguity aversion not detailed here (but shown in Table C1 of Online Appendix C), we regress the ambiguity aversion measure on the control variables. Naturally, these regressions do not imply causality. Instead, regression is a convenient tool to summarize the correlation structure of the data. We find that standard economic and demographic characteristics explain little of the variation in ambiguity aversion and, thus, the effect of ambiguity aversion on economic decisions is not subsumed by commonly used control variables.

Panel D of Table 3 shows the pairwise correlations between ambiguity aversion and education, financial literacy, self-assessed stock market knowledge, and errors on the check questions. Although this is not the main focus of our paper, we include these tests to explore the underlying nature of our measure of ambiguity aversion. Some authors argue that ambiguity aversion is primarily a mistake, caused by poor reasoning about probabilities (e.g., Al-Najjar and Weinstein, 2009; and Halevy, 2007). Others contend that ambiguity aversion is a preference and not a mistake [e.g., see the extensive review in Machina and Siniscalchi (2014) and evidence in Abdellaoui, Klibanoff, and Placido (2015)]. Although the magnitudes of the correlations are not large, Panel D of Table 3 shows that ambiguity aversion is positively correlated with college education and negatively correlated with errors on the check questions. This is consistent with other population studies such as Butler, Guiso, and Jappelli (2014) and Chew, Ratchford, and Sagi (2013). Moreover, the correlations are directionally inconsistent with the mistake view and thus provide indirect support for the preference view.

4. Ambiguity aversion: participation and the fraction of financial assets allocated to equities

This section tests the relation between ambiguity aversion and household financial behavior, in particular stock market participation and the fraction of financial assets allocated to stocks. All models reported in this section include controls for age, age-squared, gender, white, Hispanic, married, (ln) number of children (plus one), self-reported health status, education, employment status, (ln) family income, wealth, defined contribution plan and defined benefit plan participation dummies, financial literacy, trust, risk aversion, question order, errors on the check questions, missing data dummies, and a constant term.14 For all models, we report robust standard errors clustered at the household level.15

4.1. Ambiguity aversion and stock market participation

Table 4 shows the results of probit models that test the relation between ambiguity aversion and stock market participation. The table reports marginal effects, not coefficients. The dependent variable is an indicator variable equal to one if the respondent owns individual stocks or equity mutual funds and zero otherwise. In Column 1, the independent variable is Ambiguity Aversion (=50% − q), where q is the matching probability. For ease of interpretation this variable is standardized. In Column 2, the ambiguity aversion variable is Ambiguity Aversion Dummy, which is an indicator variable equal to one if the respondent’s choice indicates ambiguity aversion in the first round of the question. In Column 3, the independent variable is Ambiguity Aversion Rank, which is simply a rank transformation of the main Ambiguity Aversion variable (zero indicating the lowest level of ambiguity aversion and one the highest). We include this variable to show that the significance of our main ambiguity aversion variable is not driven by outliers. The results are similar for all three variables. Accordingly, in subsequent tables we focus primarily on the results for Ambiguity Aversion. In robustness tests, we also estimate models using a measure of ambiguity aversion in which all ambiguity-seeking individuals are recoded as ambiguity-neutral. Results are robust to this change.

Table 4. Ambiguity aversion and stock market participation.

This table shows results of probit regressions in which the dependent variable equals one if the respondent participates in the stock market. In Column 1, the key independent variable is the Ambiguity Aversion measure. In Column 2, the key independent variable is an indicator variable equal to one if the respondent is ambiguity-averse. In Column 3, the key independent variable is the rank transformation of Ambiguity Aversion. All models include a constant term and controls for age, age-squared divided by a thousand, male, white, Hispanic, married, (ln) number of children (plus one), health, education, employment status, (ln) family income, wealth divided by a hundred thousand, participation in defined contribution or defined benefit plans, financial literacy, trust, risk aversion, question order, check question score, and missing data dummies. The sample size is N = 2,943. Of the initial 3,258 respondents in our American Life Panel survey, 188 were eliminated because they took less than two minutes to answer the survey questions, another 30 subjects did not complete the ambiguity questions, and 97 had missing socio-demographic information. All nonbinary variables are standardized. The table reports marginal effects. Standard errors are clustered by household and appear in brackets. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambiguity Aversion | −0.020** [0.01] |

||

| Ambiguity Aversion Dummy | −0.039** [0.02] |

||

| Ambiguity Aversion Rank | −0.021** [0.01] |

||

| Age | −0.029 [0.07] |

−0.022 [0.07] |

−0.027 [0.07] |

| Age2 | 0.042 [0.07] |

0.036 [0.07] |

0.040 [0.07] |

| Male | 0.005 [0.02] |

0.006 [0.02] |

0.006 [0.02] |

| White | 0.045* [0.02] |

0.047* [0.02] |

0.045* [0.02] |

| Hispanic | −0.092*** [0.03] |

−0.092*** [0.03] |

−0.092*** [0.03] |

| Married | 0.051** [0.02] |

0.052** [0.02] |

0.051** [0.02] |

| Number of Children | −0.024** [0.01] |

−0.024** [0.01] |

−0.023** [0.01] |

| Health | 0.024** [0.01] |

0.025** [0.01] |

0.025** [0.01] |

| High School | −0.020 [0.06] |

−0.021 [0.06] |

−0.020 [0.06] |

| College+ | 0.036 [0.06] |

0.034 [0.06] |

0.036 [0.06] |

| Employed | 0.005 [0.02] |

0.005 [0.02] |

0.005 [0.02] |

| Family Income | 0.053*** [0.02] |

0.052*** [0.02] |

0.053*** [0.02] |

| Wealth | 0.050*** [0.01] |

0.050*** [0.01] |

0.050*** [0.01] |

| Defined Contribution | 0.056** [0.02] |

0.055** [0.02] |

0.055** [0.02] |

| Defined Benefit | −0.054** [0.02] |

−0.052** [0.02] |

−0.053** [0.02] |

| Financial Literacy | 0.068*** [0.01] |

0.068*** [0.01] |

0.068*** [0.01] |

| Trust | −0.004 [0.01] |

−0.004 [0.01] |

−0.004 [0.01] |

| Risk Aversion | 0.019** [0.01] |

0.019** [0.01] |

0.019** [0.01] |

| Question Order | 0.028 [0.02] |

0.029* [0.02] |

0.030* [0.02] |

| Errors on Check | −0.029 [0.02] |

−0.032* [0.02] |

−0.031 [0.02] |

| Controls and constant | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2,943 | 2,943 | 2,943 |

Consistent with the predictions of theory, a significant negative relation exists between ambiguity aversion and stock market participation. Further, the economic magnitude is large. The coefficient in Column 1 of Panel A implies that a one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion is associated with a 2.0 percentage point decrease in the probability of participating in the stock market (8.7% relative to the baseline rate of 23 percentage points). To put this in perspective, the implied economic magnitude of a one standard deviation change in ambiguity aversion is equivalent to a change in wealth of 0.41 standard deviations ($238,000).

Some authors argue that modest participation costs can account for a sizable fraction of nonparticipation (Haliassos and Bertaut, 1995; Gomes and Michaelides, 2005; Vissing-Jorgensen, 2002). Such costs cannot, however, explain nonparticipation among those with moderate levels of financial assets (Andersen and Nielsen, 2011; Campbell, 2006). Thus, participation by those with at least some financial assets is of particular interest. We explore this issue in Column 3 of Table 5, which displays results for the subset of respondents having financial assets of at least $500 (as in Heaton and Lucas, 2000). For this restricted sample, both the statistical and economic significance of ambiguity aversion rise. The marginal effect in Column 3 of Panel A of Table 5 implies a one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion is associated with a 3.7 percentage point decrease in the probability of participating in the stock market (9.9% relative to the baseline participation rate in this subsample of 37.3 percentage points).

Table 5. Ambiguity aversion and portfolio choice: check questions and financial assets.

This table shows results of probit regressions in which the dependent variable equals one if the respondent participates in the stock market. The main independent variable of interest in Panels A, B, and C are Ambiguity Aversion, Ambiguity Aversion Dummy, and Ambiguity Aversion Rank, respectively. Columns 2 and 4 exclude respondents whose answers to the check question were inconsistent with their earlier choices. Columns 3 and 4 exclude respondents who report financial assets of less than $500. All models include a constant term and controls for age, age-squared, male, white, Hispanic, married, (ln) number of children (plus one), health, education, employment status, (ln) family income, wealth, participation in defined contribution or defined benefit plans, financial literacy, trust, risk aversion, question order, a check question score equal to one if the subject got either of the check questions wrong (that is, they chose Box U in the first check question or Box K in the second check question), and missing data dummies. The independent variable in Panels A and C is standardized to facilitate interpretation. The table reports marginal effects. Standard errors are clustered by household and appear in brackets. · *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

| Model | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Results for ambiguity aversion | ||||

|

| ||||

| Ambiguity Aversion | −0.020** [0.01] |

−0.025* [0.01] |

−0.037** [0.02] |

−0.047** [0.02] |

| Consistent responses only | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Financial assets ≥ $500 | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Controls and constant | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2,943 | 1,746 | 1,881 | 1,199 |

|

| ||||

| Panel B: Results for ambiguity aversion dummy | ||||

|

| ||||

| Ambiguity Aversion Dummy | −0.039** [0.02] |

−0.031 [0.02] |

−0.072*** [0.03] |

−0.058* [0.03] |

| Consistent responses only | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Financial assets ≥ $500 | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Controls and constant | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2,943 | 1,746 | 1,881 | 1,199 |

|

| ||||

| Panel C: Results for ambiguity aversion rank | ||||

|

| ||||

| Ambiguity Aversion Rank | −0.021** [0.01] |

−0.023* [0.01] |

−0.039*** [0.01] |

−0.043** [0.02] |

| Consistent Responses Only | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Financial Assets ≥ $500 | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Controls and constant | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2,943 | 1,746 | 1,881 | 1,199 |

Overall, our results confirm the predictions of theory. Higher ambiguity aversion is associated with lower stock market participation. Further, the results are stronger for households with at least moderate levels of financial assets, a group whose equity nonparticipation is otherwise difficult to explain.

4.2. Measurement error in preference elicitation and other alternative explanations

Although we find a significant relation between our measure of ambiguity aversion and stock market participation, it is important to establish that our key independent variable is, in fact, a valid measure of ambiguity aversion. The reliability of subjects’ responses is one of the most common concerns that economists have with survey data. A large literature beginning with Harless and Camerer (1994) and Hey and Orme (1994) shows that subjects often provide inconsistent responses to nontrivial questions about preferences. To empirically address this issue, our module includes the two check questions described above, which test the consistency of respondents’ choices. The estimated ambiguity aversion of the respondents whose answers are inconsistent could contain greater measurement error.

For this reason, Columns 2 and 4 of Table 5 exclude respondents who gave inconsistent answers to either check question. Among this subsample, ambiguity aversion is significantly higher. Respondents who did not make errors on the check questions have measured ambiguity aversion that is 2.9 percentage points higher than the respondents who did make errors. Consistent with attenuation bias from measurement error, the ambiguity aversion variable is not significantly different from zero for those respondents who made errors on the check questions. The implied economic magnitude of the effect of ambiguity aversion on portfolio choice is also considerably larger in the subsample without errors on the check questions in Columns 2 and 4 of Table 5, consistent with less attenuation bias. For instance, in Column 2 of Panel A, the estimated marginal effect is 25% larger than the corresponding marginal effect in Column 1 for the full sample. Finding stronger results for this subsample, in which our measure of ambiguity aversion is more reliable, suggests two things. First, it supports our interpretation of the main results, while it is inconsistent with alternative explanations based on misunderstandings of the elicitation questions or measurement error. Second, our baseline estimates potentially understate the true economic magnitude of the relation between ambiguity aversion and household portfolio choice.

Another concern is that low education or cognitive skill could drive both ambiguity aversion and nonparticipation. In fact, ambiguity aversion is higher among the college-educated, a finding that is directionally inconsistent with this alternative explanation.16 Part of our sample also answered a module measuring cognitive ability. In robustness tests, we find that including an index of cognitive ability does not alter the ambiguity aversion results. Further, the correlation between cognitive ability and ambiguity aversion is not significant.

Similarly, financial illiteracy could drive both nonparticipation and ambiguity aversion. Ex ante this seems unlikely, as financial literacy explains little of the variation in ambiguity aversion (see Online Appendix C, Table C-1). But to guard against this possibility, we also control for financial literacy. The results show that financial literacy has a highly significant positive association with stock market participation, consistent with van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie (2011). Controlling for financial literacy, however, does not diminish the negative relation between ambiguity aversion and stock market participation.

Another concern is that ambiguity aversion could be correlated with risk aversion, in which case our ambiguity aversion variables could capture little incremental information. Although our elicitation method is designed to measure ambiguity aversion independent of any effect from risk aversion, ambiguity aversion and risk aversion could still be correlated, for instance, if individuals who are highly risk averse also have very strong preferences for risk over ambiguity. To control for this possibility, all specifications include our elicited measure of risk aversion. In the full sample, risk aversion is significant at the 5% level and positively related to equity market participation, but this effect dissipates in the subset of subjects having at least $500 in financial assets. We find this odd relation is driven entirely by a small subset of respondents who report extreme risk seeking in their responses. If we eliminate these risk-seeking respondents from the analysis, the relation between risk aversion and participation is insignificantly negative.17 Also, our results for foreign and own-company stock ownership, discussed in Section 5, are directionally inconsistent with the possibility that our ambiguity aversion variable inadvertently measures risk aversion.

All specifications also include a control variable for trust in other people, following Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales (2008).18 Trust is important, as the ambiguity aversion variable could conceivably measure subjects’ distrust of the experiment; that is, subjects could believe that ambiguous situations are systematically biased against them. In our sample, the relation between trust and participation is directionally consistent with Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales (2008). More important, the results for ambiguity aversion are robust to controlling for trust.

4.3. Ambiguity aversion and the fraction of financial assets allocated to stocks

Table 6 reports results from Tobit regressions that test the relation between ambiguity aversion and the fraction of financial assets allocated to stocks. Column 1 presents results using the full sample, and Column 2 presents results for the subsample of respondents with nonzero stock ownership.

Table 6. Ambiguity aversion and the fraction of financial assets allocated to stocks.

This table shows results for Tobit regressions where the dependent variable refers to the fraction of financial assets allocated to equities. Column 2 excludes respondents who do not participate in the stock market. All models include a constant term and controls for age, age-squared, male, white, Hispanic, married, (ln) number of children (plus one), health, education, employment status, (ln) family income, wealth, participation in defined contribution or defined benefit plans, financial literacy, trust, risk aversion, question order, check question score, and missing data dummies. The independent variables are standardized to facilitate interpretation. Standard errors are clustered by household and appear in brackets. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

| Model | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Ambiguity Aversion | −0.079** [0.03] |

−0.040* [0.02] |

| Equity ownership > 0 only | No | Yes |

| Controls and constant | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2,943 | 731 |

As predicted by theory (e.g., Garlappi, Uppal, and Wang, 2007; Peijnenburg, 2014), all columns show a negative relation between ambiguity aversion and the fraction of financial assets allocated to equity. This relation holds for the full sample, as well as for the portfolio allocations of stockholders. In Column 2, for an individual with nonzero ownership, the implied decrease in portfolio allocation to equity from a one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion is 4.0 percentage points (7.8% relative to the conditional average allocation of 51.4 percentage points). Overall, the results show a strong negative relation between ambiguity aversion and portfolio allocations to equity.

5. Ambiguity aversion, home-bias, and own-company stock ownership

Section 4 focused on investments in stocks as a broad asset category. In this section, we turn to the relation between ambiguity aversion and ownership of two specific categories of stocks: foreign and own-company stocks. For an ambiguity-averse investor, the attractiveness of a particular category of stock is partially determined by the investor’s familiarity with that category. French and Poterba (1991, p. 225) suggest that the unfamiliarity of foreign stocks could explain the home-bias puzzle. Several theoretical papers formalize this idea, arguing that ambiguity-averse individuals are particularly reluctant to invest in foreign stocks, which they perceive as having greater ambiguity (e.g., Boyle, Garlappi, Uppal, and Wang, 2012; Cao, Han, Hirshleifer, and Zhang, 2011; Epstein and Miao, 2003; Uppal and Wang, 2003). Following similar logic, theory suggests that ambiguity aversion can explain the own-company stock puzzle, as ambiguity-averse individuals prefer to invest in their employer’s stock, which for them has relatively low ambiguity (Boyle, Garlappi, Uppal, and Wang, 2012; Boyle, Uppal, and Wang, 2003; Cao, Han, Hirshleifer, and Zhang, 2011).

Table 7 shows the results of probit models that test the relation between ambiguity aversion and ownership of two specific categories of equity. In Columns 1 and 2, the dependent variable equals one if the individual holds foreign stock outside his 401(k) plan. In Columns 3 and 4, the dependent variable equals one if the individual owns shares of his employer’s stock outside his 401(k) plan.19 For the own-company stock ownership regressions, we limit the sample to individuals employed by someone other than themselves (i.e., the retired, self-employed, and unemployed are excluded, as own-company stock ownership is not meaningful for them). In Columns 1 and 3, the sample includes all individuals for whom we have data. In Columns 2 and 4, we limit the sample to individuals with nonzero stock ownership. All specifications include the same control variables as in Table 4, and the reported standard errors are clustered by household. The data for both dependent variables come from modules that do not perfectly overlap with our sample, so this table has fewer observations.

Table 7. Ambiguity aversion: foreign stocks and own-company stock ownership.

This table shows results for probit regressions in which the dependent variable equals one if the respondent holds foreign stock or own-company stock. Columns 1 and 2 show probit regression results for foreign stock ownership. Columns 3 and 4 show probit regression results for own-company stock ownership. Columns 2 and 4 exclude respondents who do not participate in the stock market. Columns 3 and 4 exclude respondents who are not currently employed. All models include a constant term and controls for age, age-squared, male, white, Hispanic, married, (ln) number of children (plus one), health, education, employment status, (ln) family income, wealth, participation in defined contribution or defined benefit plans, financial literacy, trust, risk aversion, question order, check question score, and missing data dummies. The independent variables are standardized to facilitate interpretation. The table reports marginal effects. Standard errors are clustered by household and appear in brackets. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

| Model | Foreign Stock Ownership

|

Own-Company Stock Ownership

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Ambiguity Aversion | −0.026** [0.01] |

−0.080** [0.03] |

0.014* [0.01] |

0.117** [0.05] |

| Equity ownership > 0 only | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Controls and constant | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 779 | 258 | 664 | 155 |

Consistent with the predictions of theory, we find a significant negative relation between ambiguity aversion and foreign stock ownership, and a significant positive relation between ambiguity aversion and own-company stock ownership. The marginal effects reported in Column 1, in which the sample includes both stock market participants and nonparticipants, imply that a one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion is associated with a 2.6 percentage point decrease in the probability of owning foreign stocks (19.5% relative to the baseline rate of 13.3 percentage points). The results in Column 2 show that the negative relation between ambiguity aversion and foreign stock ownership is not simply a result of the negative relation between ambiguity aversion and equity ownership. Even among equity market participants, higher ambiguity aversion is negatively associated with ownership of foreign stocks. Once again, the implied economic magnitude is large. A one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion is associated with an 8.0 percentage point decrease in the probability of foreign stock ownership (29.6% relative to the baseline rate of 27.0 percentage points).

Also consistent with the theory’s predictions, we find a significant positive relation between ambiguity aversion and own-company stock ownership. Marginal effects reported in Column 3, where the sample includes both stock market participants and nonparticipants, imply that a one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion is associated with a 1.4 percentage point increase in the probability of own-company stock ownership (28.0% relative to the baseline rate of 5.0 percentage points). Although this coefficient is significant at only the 10% level, the result is intriguing as it suggests that the ambiguity-averse are more likely to invest in own-company stock, even relative to the alternative of nonparticipation in any form of equity. Furthermore, Column 4 shows that the positive relation between ambiguity aversion and own-company stock ownership is significant among the sample of stock market participants. Once again, the implied economic magnitude is large. A one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion is associated with an 11.7 percentage point increase in own-company stock ownership.

Table 7 additionally presents the first direct empirical evidence that ambiguity aversion is significantly related to both the home-bias and the own-company stock puzzles. These results are inconsistent with the possibility that our measure of ambiguity aversion inadvertently captures risk aversion. Higher risk aversion should increase the probability of foreign stock ownership because of the diversification benefits and decrease the probability of own-company stock ownership because of portfolio diversification and the background risk associated with investing in one’s employer. For both foreign and own-company stock, the directional predictions of ambiguity aversion are exactly the opposite. More generally, the results in Table 7 pose a challenge to alternative interpretations of our ambiguity aversion measure. Any alternative interpretation would have to be consistent with both a negative relation between our measure and most forms of equity, and a positive relation with own-company stock.

6. Ambiguity aversion and stock market competence: Participation and under-diversification

The prior section tested the effect of ambiguity aversion on investment decisions for unfamiliar assets (foreign stocks) and familiar assets (own-company stock). In this section, we further test how the effect of ambiguity aversion differs across investors, depending on the investors’ familiarity (or competence) with the overall stock market.

6.1. Ambiguity aversion, stock market competence, and stock market participation

Our tests are motivated by the competence hypothesis of Heath and Tversky (1991), that most people are ambiguity-averse towards decisions in areas that are unfamiliar or purely chance-based ambiguity (such as an Ellsberg urn), but that ambiguity aversion is reduced for decisions in areas for which the individual sees himself as knowledgeable or competent. Hence, individuals with high stock market competence would display less ambiguity aversion toward financial decisions, compared with Ellsberg urns (a low competence task). Conversely, individuals with low stock market competence would display similar ambiguity aversion toward financial decisions and Ellsberg urns, as they do not feel competent in either setting. This implies that the relation between ambiguity aversion (based on Ellsberg urns) and portfolio choice should be stronger for those with relatively low stock market competence.

In this subsection, we use two direct measures of low stock market competence. First, we identify respondents whose self-assessed financial knowledge is very low.20 Second, we identify respondents who made errors on the financial literacy questions. We then separately estimate the effect of ambiguity aversion within two subgroups: those with high competence and those with low competence. We acknowledge the possibility that these measures of stock market competence could be endogenous. For example, individuals who own stocks can learn from their experience, creating a reverse causality problem. Alternatively, both stock ownership and stock market competence could be determined by some other factor [for a lucid discussion of potential endogeneity problems in studies of financial literacy, see van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie (2011)]. The potential endogeneity problems, however, primarily affect the interpretation of the coefficients for the stock market competence variables, not the interaction of stock market competence with ambiguity aversion.

In Table 8 we test how ambiguity aversion and stock market competence interact to affect stock market participation. For ease of comparison, Column 1 repeats the results from Table 4, which shows the relation between ambiguity aversion and stock market participation controlling for the level of stock market competence (proxied by the number of correct responses on the financial literacy questions). In contrast, Columns 2 and 3 also allow stock market competence to affect the sensitivity of the relation between ambiguity aversion and stock market participation. In these columns we estimate the effect of ambiguity aversion separately for the low and high self-assessed stock market knowledge (or financial literacy) groups. In these specifications, we also replace the financial literacy control variable with the variable used to divide the sample (i.e., in Column 2, the financial literacy control variable is replaced with self-assessed stock market knowledge instead of the number of correct answers on the financial literacy questions). Aside from these changes, the regressions are identical to those in Table 4.

Table 8. Ambiguity aversion and stock market competence.

This table shows results for probit regressions in which the dependent variable is equals one if the respondent participates in the stock market. Column 1 includes no interaction term between stock market competence and Ambiguity Aversion (AA). Column 2 includes interaction terms between the level of self-assessed stock market knowledge and Ambiguity Aversion, and Column (3) includes interaction terms between the level of financial literacy and Ambiguity Aversion. Respondents have low literacy if their answer to one or more of the three financial literacy questions is wrong. Respondents have low knowledge if they answer “very low” to the question: “How would you rate your knowledge about the stock market?” All models include a constant term and controls for age, age-squared, male, white, Hispanic, married, (ln) number of children (plus one), health, education, employment status, (ln) family income, wealth, participation in defined contribution or defined benefit retirement plans, financial literacy, trust, risk aversion, question order, check question score, and missing data dummies. The independent variables are standardized to facilitate interpretation. The table reports marginal effects. Standard errors are clustered by household and appear in brackets. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

| Model | No Interaction (1) |

Self-Assessed Knowledge (2) |

Financial Literacy (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambiguity Aversion | −0.020** [0.01] |

||

| AA: low stock market competence | −0.046*** [0.02] |

−0.033** [0.01] |

|

| AA: high stock market competence | −0.012 [0.01] |

−0.009 [0.01] |

|

| Stock market competence | 0.068*** [0.01] |

0.185*** [0.02] |

0.124*** [0.02] |

| Controls and constant | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2,943 | 2,943 | 2,943 |

Consistent with the Heath and Tversky (1991) competence hypothesis, Table 8 shows that the effect of ambiguity aversion is always more statistically significant in the subset of respondents reporting low stock market competence. For both measures of stock market competence, a stronger negative relation exists between ambiguity aversion and participation for individuals with lower competence. For example, the results in Column 2 imply that a one standard deviation increase in ambiguity aversion is associated with a 4.6 percentage point decrease in stock market participation for an individual with low stock market competence, compared with an insignificant 1.2 percentage point decrease for an individual with high stock market competence. However, the difference in the effect of ambiguity aversion between the high and low competence groups is not statistically significantly, so we cannot conclude that the effect of ambiguity aversion is different for the low and high competence groups.

6.2. Ambiguity aversion, stock market competence, and portfolio under-diversification

Conditional on stock market participation, many households hold equity portfolios that are extremely under-diversified relative to mean-variance efficient benchmarks (Blume and Friend, 1975; Goetzmann and Kumar, 2008; Polkovnichenko, 2005). The theoretical model of Boyle, Garlappi, Uppal, and Wang (2012) suggests that ambiguity aversion can explain this puzzle. In their model, portfolio diversification is determined by the relative ambiguity of the overall market versus that of a few undiversified, but potentially familiar, stocks. An investor who is ambiguity-averse, and who views the overall market as more ambiguous than the familiar stocks, will hold an undiversified portfolio of familiar stocks. An ambiguity-averse investor who views the overall market as highly ambiguous, and does not view any individual stocks as familiar, will not participate at all. An ambiguity-averse investor who does not view the overall market as highly ambiguous will hold a diversified portfolio. In this subsection, we test these predictions using our two measures of stock market competence (self-assessed stock market knowledge and financial literacy) as measures of investors’ perceived ambiguity of the overall stock market. We then test whether the interaction of ambiguity aversion and perceived ambiguity can help explain the portfolio under-diversification puzzle.

Table 9 presents the results. As our goal is to examine allocations of equity owners, we limit the sample to only those who participate in the stock market. In Columns 1 to 3, we report probit estimates of models in which the dependent variable is equal to one for respondents who own individual stocks and zero otherwise. In Columns 4 to 6, we report estimates from a Tobit model in which the dependent variable is the fraction of equity allocated to individual stocks.21 We include both specifications for completeness but focus our discussion on the Tobit results, as Calvet, Campbell, and Sodini (2007, 2009) present evidence suggesting that the proportion of equity held in individual stocks is a reasonable proxy for portfolio under-diversification. Furthermore, the median individual stock owner in our sample owns only two stocks, and over 86% hold fewer than eight stocks. Our measures of individual stock ownership do not include foreign stocks or own-company stock. The measures of stock market competence pertain to knowledge about stocks in general (i.e., about the overall market), but we lack measures of whether there are certain “familiar” stocks available to the individual (and if such a measure were available, reverse causality would be a concern).

Table 9. Ambiguity aversion and under-diversification.

This table shows results for regressions in which the dependent variables indicate ownership of individual stocks. Columns 1, 2, and 3 show probit regression results in which the dependent variable equals one if the respondent reports ownership of individual stocks. Columns 4, 5, and 6 show Tobit regression results in which the dependent variable is the fraction of equity invested in individual stocks. Columns 1 and 4 include no interaction term between stock market competence and Ambiguity Aversion (AA). Columns 2 and 5 include interaction terms between the level of self-assessed stock market knowledge and Ambiguity Aversion, and Columns 3 and 6 include interaction terms between the level of financial literacy and Ambiguity Aversion. Respondents have low literacy if their answer to one or more of the three financial literacy questions is wrong. Respondents have low knowledge if they answer “very low” to the question: “How would you rate your knowledge about the stock market?” All models include a constant term and controls for age, age-squared, male, white, Hispanic, married, (ln) number of children (plus one), health, education, employment status, (ln) family income, wealth, participation in defined contribution or defined benefit plans, financial literacy, trust, risk aversion, question order, check question score, and missing data dummies. The independent variables are standardized to facilitate interpretation. The table reports marginal effects. Standard errors are clustered by household and appear in brackets. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

| Model | Individual stock ownership

|

Fraction of equity in individual stocks

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Interaction (1) |

Self-Assessed Stock Market Knowledge (2) |

Financial Literacy (3) |

No Interaction (4) |

Self-Assessed Stock Market Knowledge (5) |

Financial Literacy (6) |

|

| Ambiguity Aversion | −0.087*** [0.02] |

−0.115*** [0.01] |

||||

| AA: low stock market competence | −0.017 [0.06] |

−0.044 [0.04] |

0.459*** [0.04] |

0.105*** [0.02] |

||

| AA: high stock market competence | −0.096*** [0.02] |

−0.100*** [0.03] |

−0.134*** [0.01] |

−0.171*** [0.01] |

||

| Stock market competence | −0.011 [0.03] |

0.063 [0.07] |

−0.037 [0.05] |

0.051 [0.04] |

−0.048 [0.07] |

0.043 [0.06] |

| Controls and constant | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 701 | 701 | 701 | 319 | 319 | 319 |

Results in Columns 1 and 4, in which we do not consider stock market competence, show a significant negative relation between ambiguity aversion and ownership of individual stocks. A one standard deviation increase in an individual’s ambiguity aversion implies a 8.7 percentage point reduction in the probability that an equity owner holds individual stocks (12.7% relative to the baseline rate of 68.5 percentage points) and implies a 11.5 percentage point lower portfolio allocation to individual stocks (27.3% relative to the conditional average allocation of 42.2 percentage points). The theoretical direction of the effect of ambiguity aversion is conditional on the relative perceived ambiguity of the overall market versus that of individual stocks. The negative relation that we find implies that, in aggregate, investors perceive that the returns of individual stocks have greater ambiguity than the returns of the overall market.

In Columns 2 and 5, we split the sample based on self-assessed stock market knowledge, and in Columns 3 and 6, we split the sample based on correct answers to the financial literacy questions. Consistent with the model of Boyle, Garlappi, Uppal, and Wang (2012), a negative relation exists between ambiguity aversion and individual stock ownership for investors who do not view the overall market as highly ambiguous. Although theory predicts a positive relation between ambiguity aversion and under-diversification for investors who view the market as highly ambiguous, in the probit regressions the relation is not significant.