Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether treatment (surgery, radiation therapy, and endocrine therapy) contributes to racial disparities in outcomes of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

Patients and Methods

The analysis included 8,184 non-Hispanic White and 954 non-Hispanic Black women diagnosed with DCIS between 1996 and 2011 and identified in the Missouri Cancer Registry. Logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) of treatment for race. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) of ipsilateral and contralateral breast tumors for race.

Results

There was no significant difference between Black and White women in utilization of mastectomy (OR 1.16; 95% CI 0.99–1.35) or endocrine therapy (OR 1.19; 95% CI 0.94–1.51). Despite no significant difference in underutilization of radiation therapy (OR 1.14; 95% CI 0.92–1.42), Black women had higher odds of radiation delay, defined as at least eight weeks between surgery and radiation (OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.55–2.37). Among 9,138 patients, 184 had ipsilateral breast tumors (IBTs) and 326 had contralateral breast tumors (CBTs). Black women had a higher risk of IBTs (HR 1.69; 95% CI 1.15–2.50) and a comparable risk of CBTs (HR 1.19; 95% CI 0.84–1.68), which were independent of pathological features and treatment.

Conclusion

Racial differences in DCIS treatment and outcomes exist in Missouri. This study could not completely explain the higher risk of IBTs in Black women. Future studies should identify differences in timely initiation and completion of treatment, which may contribute to the racial difference in IBTs after DCIS.

Keywords: Breast cancer, ductal carcinoma in situ, race, second breast tumors, cancer disparity

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) has increased greatly over the last 30 years, mostly due to increased awareness and use of screening mammography [1]. Treatment options for DCIS include mastectomy alone and breast-conserving surgery (BCS) with or without radiation or endocrine therapy [2]. Endocrine therapies recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology for reduction of invasive breast cancer risk include selective estrogen receptor modulators (e.g. tamoxifen) and aromatase inhibitors (e.g. exemestane). Only tamoxifen is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for prevention of invasive breast cancer after DCIS [3]. With treatment, less than 2% of women with DCIS will die from breast cancer in the decade after diagnosis [4]. However, the presence of DCIS reflects increased risk for invasive breast cancer, as 11–19% of women with DCIS develop a second breast cancer within 10 years of diagnosis [5, 6], with similar rates 10 or more years after diagnosis [7].

Recent studies showed that the risk of developing a second breast tumor after DCIS varies by race [8–12]. Compared with White women, Black women are far more likely to develop additional breast tumors after DCIS. Racial differences in risk of second breast tumors are not completely explained by pathological features, surgical approach, and utilization of radiation therapy [8, 12]. Several population-based studies have consistently reported that Black women with invasive breast cancer are less likely than White women with invasive breast cancer to start or complete adjuvant therapy [13–17]. However, analyses of DCIS treatment by race were largely conducted in hospital-based studies [18–23], with the majority showing comparable odds of surgical treatment and adjuvant therapy use. It remains unclear if endocrine therapy and surgical margins, two factors that affect recurrence risk [3, 9, 27], contribute to racial disparities in second breast tumor risk after DCIS. In this study, we quantified race-associated differences in DCIS treatment and disparities in the risk of second breast tumors using the population-based resources of the Missouri Cancer Registry.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data source

De-identified Missouri Cancer Registry (MCR) data were used in this study. Since 1995, the MCR has been a member of the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and compliant with its data collection and coding rules. To determine case reportability, the MCR follows the rules of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute. The MCR periodically conducts case completeness and data quality audits as required by the NPCR. Due to the accuracy and completeness of data elements, the MCR has been certified by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries since 2001 (for 1998 data). The MCR includes more than 95% of all incident cases of cancer in Missouri. Similar to the SEER program, the MCR collects demographic, tumor, and primary treatment information. If multiple surgical procedures are conducted on a primary site for a given case, the most invasive surgical procedure is recorded for that primary site. In addition, the MCR database has information on start dates of surgical treatment and adjuvant therapies and surgical margin status. Dates of treatment were available for over 90% of cases. The Institutional Review Boards of the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services and Washington University in St. Louis reviewed the study protocol and determined it to be exempt.

Patients

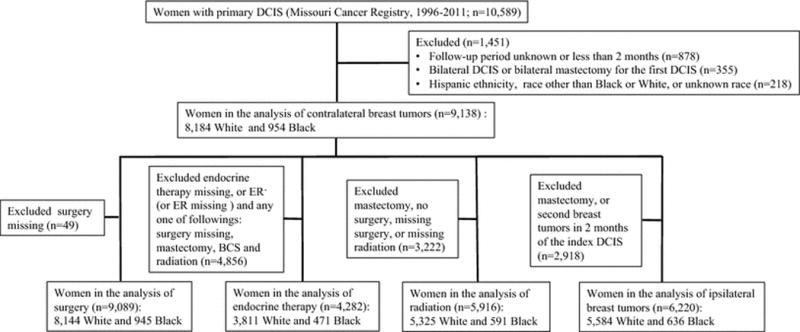

We identified all women who were diagnosed with first primary DCIS between January 1996 and October 2011 and were followed through December 31, 2011 (n=10,589). We excluded women who were followed for less than two months or had an indeterminate follow-up period (n=878) and those who had bilateral DCIS and/or bilateral mastectomy (n=355). As nonHispanic White and Black women were 99% of eligible cases, we also excluded women of other races, unknown race, or Hispanic ethnicity (n=218) from the study. We divided patients by race into mutually exclusive categories of non-Hispanic White (White) and non-Hispanic Black (Black). Thus, the analytic sample consisted of 9,138 women. Figure 1 shows the exclusion criteria and sample size for the analyses of DCIS treatment and outcomes.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of cohort inclusion and exclusion criteria for women with primary ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in the Missouri Cancer Registry

Treatment

We used information on surgical treatment and adjuvant therapy that were given during the first course of treatment. Treatment specifically for tumor progression or recurrence was coded as subsequent treatment in the MCR and was not included in the analysis. We defined breast-conserving surgery (BCS) as partial mastectomy with or without nipple resection, segmental mastectomy, lumpectomy, excisional biopsy, or local tumor destruction not otherwise specified. We defined mastectomy as all codes including the words “total mastectomy” or “radical mastectomy”, excluding codes with the words “bilateral” or “contralateral”. Based on the findings of Huang et al [28], we defined radiation delay as an interval of eight weeks or longer between BCS and the start of radiation therapy. Radiation therapy use was categorized as timely initiation, delayed initiation, and underutilization (no radiation). Aromatase inhibitors have been used for DCIS in a small number of women [18], although it has not been approved by the FDA. Thus, both tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors were included in the analysis of endocrine therapy for DCIS.

Outcomes

We defined a second breast tumor as an ipsilateral breast tumor (IBT) or contralateral breast tumor (CBT) diagnosed at least two months after the first DCIS. IBTs were defined as any histological type of carcinoma in situ or invasive cancer in the ipsilateral breast and CBTs were defined as any histological type of carcinoma in situ or invasive cancer in the contralateral breast. We calculated person-months from 2 months after the first DCIS until the first of the following dates occurred: date of second breast tumors, death, last follow-up, or December 31, 2011.

Statistical analysis

We compared baseline characteristics between two racial groups using independent-samples t tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. We conducted logistic regression analyses to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) of utilization of surgery (BCS, mastectomy, or no surgical treatment), adjuvant radiation (timely initiation, delayed initiation, or no radiation) and endocrine therapy. When evaluating surgery utilization we adjusted for age (<50, 50–<59, 60–69, or ≥70), year of diagnosis (1996–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, or 2010–2011), health insurance (private, Medicare, Medicaid/uninsured, or other/unknown), marital status (married/partnered, non-married, or unknown), tumor grade (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, or unknown), tumor size (<2cm, ≥2cm, or unknown), histology (comedo, papillary, cribriform, solid, or NOS), and estrogen receptor (ER) status (positive, negative, or unknown). The analysis of radiation utilization was restricted to women who had undergone definitive BCS and adjusted for surgical margins (clear, positive, or unknown) in addition to the aforementioned covariates. Women who had ER+ DCIS or did not receive radiation following BCS were included in the analysis of endocrine therapy, which is consistent with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for endocrine therapy for DCIS [2]. The analysis of endocrine therapy was further adjusted for surgery (no surgical treatment, BCS, mastectomy, or unknown), and radiation therapy (yes, no, or unknown).

We restricted the analysis of IBTs to women with BCS or no surgical treatment. We included all patients, regardless of surgical category, in the analysis of CBTs. To compare race-associated 10-year probabilities of IBTs and CBTs, we utilized Kaplan-Meier estimates and the log-rank test. To compare risks of IBTs and CBTs by race, we performed Cox proportional hazards regression analyses to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) of IBTs and CBTs. We calculated Schoenfield residuals to confirm the proportional hazards assumption. Cox proportional hazards regression models were adjusted for age and year of diagnosis, with additional variables added in the following order: insurance type, tumor characteristics (grade, size, histology, estrogen receptor status), and treatment characteristics (surgery, surgical margin, radiation, endocrine therapy). We categorized these covariates as above. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was assessed as two-sided P <0.05.

RESULTS

Table 1 lists demographic and tumor characteristics for 9,138 women diagnosed with primary DCIS. Within this cohort, 8,184 women (89.6%) were White and 954 women (10.4%) were Black. The mean age was 60.7 years for White women and 59.5 years for Black women (P=0.005). A greater percentage of Black cases (82.6%) than White cases (78.9%) were diagnosed after 1999 (P<.0001). Median follow-up time was 77 months (range 2 to 191 months) for White women and 68 months (range 2 to 191 months) for their Black counterparts (P<0.001). Black women (38.6%) were more likely than White women (27.8%) to have tumors 2 cm or larger at the time of diagnosis (P<0.0001). However, Black women (36.7%) were less likely to have poorly differentiated tumors than White women (42.7%; P=0.006). There was no significant difference in ER positivity between Black and White women (83.8% vs 82%; P=0.35).

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with ductal carcinoma in situ by race in the Missouri Cancer Registry, 1996–2011

| NH-White N (%) |

NH-Black N (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 8184 | 954 | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60.7 (12.5) | 59.5 (12.6) | 0.005 |

| <50 | 1695 (20.7) | 226 (23.7) | |

| 50–59 | 2211 (27.0) | 263 (27.6) | |

| 60–69 | 2103 (25.7) | 259 (27.2) | |

| ≥70 | 2175 (26.6) | 206 (21.6) | 0.006 |

| Length of follow-up, months | |||

| Median (range) | 77 (2–191) | 68 (2–191) | <.0001 |

| 6–11 | 532 (6.5) | 91 (9.5) | |

| 12–59 | 2679 (32.7) | 341 (35.7) | |

| 60–119 | 2841 (34.7) | 322 (33.8) | |

| ≥120 | 2132 (26.1) | 200 (21.0) | 0.0001 |

| Year of the first DCIS diagnosis | |||

| 1996–1999 | 1729 (21.1) | 166 (17.4) | |

| 2000–2004 | 2677 (32.7) | 292 (30.6) | |

| 2005–2009 | 2845 (34.8) | 333 (34.9) | |

| 2010–2011 | 933 (11.4) | 163 (17.1) | <.0001 |

| Health insurance | |||

| Private | 1612 (59.3) | 191 (49.6) | |

| Medicare | 1001 (36.8) | 135 (35.1) | |

| Medicaid or uninsured | 107 (3.9) | 59 (15.3) | |

| Other or missing | 5464 | 569 | <.0001 |

| Histological subtype | |||

| Not otherwise specified | 5872 (71.8) | 650 (68.1) | |

| Comedo | 1010 (12.3) | 112 (11.7) | |

| Papillary | 560 (6.8) | 115 (12.1) | |

| Cribiform | 431 (5.3) | 45 (4.7) | |

| Solid | 311 (3.8) | 32 (3.4) | <.0001 |

| Grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 1147 (20.9) | 172 (24.8) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 1992 (36.4) | 267 (38.5) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 2341 (42.7) | 255 (36.7) | 0.006 |

| Missing | 2704 | 260 | |

| Tumor size, cm | |||

| <2.0 | 1851 (72.2) | 210 (61.4) | |

| ≥2.0 | 714 (27.8) | 132 (38.6) | <.0001 |

| Missing | 5619 | 612 | |

| Estrogen receptor | |||

| Negative | 639 (18.0) | 75 (16.2) | |

| Positive | 2907 (82.0) | 387 (83.8) | 0.35 |

| Missing | 4638 | 492 | |

| Surgery for first DCIS | |||

| None | 184 (2.3) | 35 (3.7) | |

| BCS | 5380 (66.1) | 594 (62.9) | |

| Mastectomy | 2580 (31.7) | 316 (33.4) | 0.01 |

| Missing | 40 | 9 | |

| Surgical margin† | |||

| Clear | 7258 (96.2) | 823 (94.0) | |

| Positive | 286 (3.8) | 53 (6.1) | 0.001 |

| Missing | 456 | 43 | |

| Radiation therapy for first DCIS | |||

| No | 4254 (52.5) | 499 (52.5) | |

| Yes | 3851 (47.5) | 451 (47.5) | 0.98 |

| Missing | 79 | 4 | |

| Surgery and radiation therapy for first DCIS | |||

| No surgery | 184 (2.3) | 35 (3.7) | |

| BCS alone | 1566 (19.3) | 158 (16.7) | |

| BCS and radiation | 3773 (46.6) | 436 (46.1) | |

| Mastectomy | 2580 (31.8) | 316 (33.4) | 0.01 |

| Missing | 81 | 9 | |

| Weeks from surgery to radiation, mean (SD)‡ | 6.3 (3.8) | 8.1 (5.4) | <.0001 |

| Guideline concordant use of endocrine therapy§ | |||

| No | 2423 (63.6) | 271 (57.5) | 0.01 |

| Yes | 1388 (36.4) | 200 (42.5) | |

| Missing | 217 | 33 |

NH: non-Hispanic

The comparison was made in 8,919 patients with surgical treatment.

The analysis was limited to the patients who received radiation therapy following definitive breast-conserving surgery.

The analysis included the patients with estrogen receptor-positive DCIS and the patients with breast-conserving surgery alone.

Treatment

Table 1 displays treatment characteristics by race. Compared with White women, more Black women had no surgical treatment (3.7% vs 2.3%) for primary DCIS or underwent mastectomy (33.4% vs 31.7%). In addition, 6.1% of Black women had positive surgical margins versus 3.8% of White women. Guideline-concordant use of endocrine therapy was observed in 42.5% of Black women and 36.4% of White women. The percentage of women who received radiation was 47.5% in both groups. However, mean time from definitive BCS to radiation was 8.1 weeks for Black women and 6.3 weeks for their White counterparts. After BCS, 26.1% of Black women and 29.1% of White women did not undergo radiation therapy, and 28.6% of Black women and 16.6% of White women experienced a delay in initiation of radiation therapy.

Table 2 shows adjusted odds ratios for treatment. After adjusting for age, year of diagnosis, health insurance, and tumor characteristics, we did not observe statistically significant differences in the odds of receiving mastectomy between Black and White women (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.99–1.35). Black women had higher odds of underutilization of surgical treatment (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.20–2.60). Among women with ER+ DCIS and women who did not receive radiation therapy following BCS, we did not observe a significant difference in guideline-concordant use of endocrine therapy between racial groups (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.94–1.51) after adjustment for demographic and clinical factors. There was no significant racial difference in the odds of underutilization of radiation therapy following definitive BCS (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.92–1.42). However, Black women had higher odds of experiencing an eight-week or longer delay between BCS and radiation (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.55–2.37).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of treatment for non-Hispanic Black versus non-Hispanic White women with primary ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast

| White

|

Black

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | 95% CI | N | OR | 95% CI | |

| Mastectomy† | 2580 | 1.00 | Reference | 316 | 1.16 | 0.99, 1.35 |

| No surgical treatment† | 184 | 1.00 | Reference | 35 | 1.76 | 1.20, 2.60 |

| Endocrine therapy‡ | 1388 | 1.00 | Reference | 200 | 1.19 | 0.94, 1.51 |

| Delayed radiation therapy§ | 884 | 1.00 | Reference | 169 | 1.92 | 1.55, 2.37 |

| No radiation therapy§ | 1548 | 1.00 | Reference | 154 | 1.14 | 0.92, 1.42 |

Mastectomy and no surgical treatment were compared with breast-conserving surgery. The ORs were adjusted for age, year of diagnosis, health insurance, tumor grade, tumor size, histology, and estrogen receptor status.

The analysis included patients with estrogen receptor-positive DCIS and patients with breast conserving surgery only. The OR was adjusted for age, year of diagnosis, insurance, tumor grade, tumor size, histology, estrogen receptor status, surgery, surgical margin, and radiation therapy.

The analysis was conducted in women with breast-conserving surgery and complete data on timing of surgery and first radiation therapy. Radiation delay was defined as an interval of eight weeks or longer between breast conserving surgery and the start of radiation therapy. Delayed initiation of radiation therapy and no radiation therapy were compared with timely initiation of radiation therapy. The ORs were adjusted for age, surgery, surgical margins, year of diagnosis, health insurance, tumor grade, tumor size, histology, and estrogen receptor status.

Outcomes

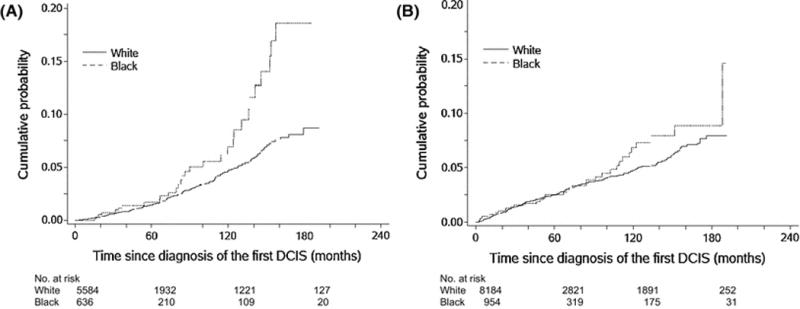

Among 6,220 women who had BCS or no surgery, 196 women (3.1%) developed subsequent ipsilateral breast tumors (IBTs) during the 72-month followup. Of these 60 (30.6%) were carcinoma in situ and 136 (69.4%) were invasive cancer. Race-specific 10-year cumulative incidence rates are shown in Figure 2 for IBTs and CBTs. Black women had a greater 10-year cumulative incidence of IBTs than White women (6.9% vs 4.7%, P=0.001). Among the entire cohort (n=9,138, regardless of type of surgery), 326 women (3.6%) had contralateral breast tumors (CBTs) during the 76-month followup, of which 100 (30.7%) were carcinoma in situ and 226 (69.4%) were invasive cancer. As with IBTs, Black women had a greater cumulative incidence of CBTs than White women, with a 10-year rate of 6.8% in Black vs. 4.8% in White women (P=0.27).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidences of ipsilateral second breast tumors (A) and contralateral breast tumors (B) among non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black women with ductal carcinoma in situ

Table 3 shows the adjusted HRs for IBTs and CBTs. Black women had a significantly higher risk of IBTs after adjusting for age and year of diagnosis (HR, 1.81; 95% CI 1.23–2.67). Further adjustment for insurance type, tumor characteristics, and treatment did not meaningfully attenuate the HR (HR, 1.69; 95% CI 1.15–2.50). Black women also had a higher risk of CBTs, but this difference was not statistically significant (HR 1.20; 95% CI 0.85–1.69) after adjusting for age and year of diagnosis. Addition of insurance type, tumor characteristics, and treatment to subsequent models for CBTs led to minimal changes in the HR (HR, 1.19; 95% CI 0.84–1.68).

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of ipsilateral and contralateral breast tumors for non-Hispanic Black versus non-Hispanic White women with primary ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast

| Person-months | No. of events | Model 1† | Model 2‡ | Model 3§ | Model 4* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Ipsilateral breast tumors | ||||||||||

| White | 446380 | 165 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Black | 46093 | 31 | 1.81 | 1.23, 2.67 | 1.79 | 1.21, 2.63 | 1.73 | 1.17, 2.55 | 1.69 | 1.15, 2.50 |

| Contralateral breast tumors | ||||||||||

| White | 677149 | 289 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Black | 71301 | 37 | 1.20 | 0.85, 1.69 | 1.20 | 0.85, 1.69 | 1.16 | 0.82, 1.63 | 1.19 | 0.84, 1.68 |

The HRs were adjusted for age and year of diagnosis of the index ductal carcinoma in situ.

The HRs were further adjusted for type of health insurance.

The HRs were adjusted for tumor characteristics including grade, size, histology, and estrogen receptor status in addition to the covariates included in Model 2.

The HRs were adjusted for treatment including surgery, surgical margin status (in the analysis of ipsilateral breast tumors), radiation therapy, and endocrine therapy in addition to the covariates included in Model 3.

DISCUSSION

Using a large, statewide cancer registry, we observed significant differences in the timing of initiation of radiation therapy following BCS and the risk of developing second primary breast tumors between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White women with DCIS. There was no significant racial difference in the odds of guideline-concordant use of endocrine therapy. Both groups had the same rates of radiation therapy following BCS, but Black women were much more likely to initiate radiation therapy eight or more weeks after BCS. Although Black women were less likely than White women to undergo surgical treatment, the absolute difference was too small to be clinically relevant. Black women had a higher risk of developing IBTs, and the difference in risk was not completely attributable to demographic and tumor characteristics, insurance type, and treatment received. Although Black women also had a higher risk of CBTs, the difference was not statistically significant.

The NCCN guidelines recommend 5 years of tamoxifen for women with ER+ DCIS, as well as women with DCIS who do not receive radiation therapy following BCS [2]. The guidelines-concordant use of endocrine therapy was observed in 36.4% of White women and 42.5% of Black women in our study. The difference was not statistically significant after adjustment for covariates. In a contemporary cohort of women with DCIS identified from the National Cancer Database (n=206,255), only 45% of women with ER+ tumors and 21.6% of women with BCS alone received adjuvant endocrine therapy [19]. The likelihood of endocrine therapy use was significantly higher for Black women in that study (OR 1.04; 95% CI 1.00–1.07; P=0.03); however, the absolute difference was only 3.3%. A survey of women with DCIS identified from the California Cancer Registry revealed that 23% of endocrine therapy users reported discontinuation by a median of 11 months [24]. Among women with invasive breast cancer, Hershman et al [29] observed that Black women were less likely to be adherent to endocrine therapy in comparison to White women. This association may also exist in women with DCIS though data are lacking. If this is the case, the population of Black women starting endocrine therapy may not experience the same degree of benefit as White women starting endocrine therapy. Due to the lack of detailed pharmacy records in the MCR, we could not assess potential differences in adherence and persistence to endocrine therapy between Black and White patients with DCIS.

This study may be the first to identify an increased risk of delayed radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery in Black women with DCIS. Black women in this population-based cohort were more likely to have positive surgical margins, which may have led to additional surgeries and delayed radiation. However, the difference in risk of radiation delay persisted after adjustment for insurance status and surgical margins. Also, it may be more difficult for uninsured or underinsured women to start radiation therapy in a timely manner. There has been limited study on access to radiation therapy in Missouri, but underinsured and uninsured women throughout the state may be facing barriers to timely radiation initiation, especially if they are diagnosed at facilities without on-site radiation oncologists.

The clinical relevance of the observed difference in timely initiation of radiation therapy following BCS between Black and White women with DCIS remains unknown. Among women with invasive breast cancer, receipt of radiation therapy eight or more weeks after BCS has been associated with increased risk of local recurrence compared with receipt of radiation therapy within eight weeks of BCS [17, 28]. Using the Missouri Cancer Registry data, we found that the risk of IBTs was increased by 26% (HR 1.26; 95% CI 1.00–1.59; P=0.049) in women with DCIS who received radiation therapy eight or more weeks after BCS compared with those who received radiation therapy within eight weeks of BCS [30]. Due to limited power, this preliminary result needs to be confirmed.

Even after adjusting for age, insurance, tumor characteristics, and treatment received, the elevated risk of IBTs in Black women persisted in our study. None of these variables significantly reduced the association between race and IBT risk. The observed racial difference in IBT risk after DCIS is in agreement with some, although not all, population-based studies [8–11, 31]. In a study of the 1992–1999 SEER data, Smith et al [31] reported that the risk of IBTs was increased by 39% for Black women compared with White women but the difference was not statistically significant. In that study, 3,409 older women (aged 66 or older) were included and only 270 were Black. Our recent analysis of the 1988–2009 SEER data included more than 100,000 women (aged 20–84), of which almost 10,000 were Black [8]. We observed that the risk of IBTs was significantly increased by 46% for Black women, which was not attributable to surgical approach, radiation therapy, and pathological features. The contributions of endocrine therapy and surgical margin status to the observed racial difference in IBT risk were not assessed in that study due to lack of relevant data. More detailed information on treatment is available in the MCR. Adjustment for surgical margins and endocrine therapy did not significantly reduce the association between Black race and IBT risk among women with DCIS in the MCR.

We did not find a significant association between race and CBT risk in the current study. However, multiple population-based studies, including SEER-based studies, found that Black women had higher risk of both ipsilateral and contralateral tumors than White women [8, 10, 11]. It remains unclear if the observed racial difference in CBT risk reflects underutilization of endocrine therapy in Black women. We did not observe a significant difference in endocrine therapy use between Black and White women in Missouri that is not covered by the SEER program. This might explain, at least in part, the comparable risk of CBTs between the two racial groups in Missouri. There may also be differences in access to care in Missouri that mitigate the association between Black race and CBTs after primary DCIS. Future studies should continue to explore the relationship between race, mammography use, treatment regimens, and CBT risk.

This is the first population-based study to examine DCIS treatment and outcome disparities in the Midwest. Unlike previous population-based studies, it included data on endocrine therapy initiation and surgical margins. However, this study had some limitations. Our sample size was not sufficiently large to compare survival outcomes or detect potential differences in patterns of invasive breast cancer recurrences versus DCIS recurrences. Similarly to the SEER and other cancer registries, the MCR did not collect data on completion of radiation or endocrine therapy. We did not acquire information on geographical location for this study, which would have allowed us to compare outcomes among rural and urban residents and assess the effect of socioeconomic status. Due to the lack of information on comorbid conditions, we were unable to assess their impact on treatment received and outcomes.

In conclusion, this population-based study provides evidence that Black women had a significantly higher risk of developing IBTs after primary DCIS compared with White women in Missouri. The difference was not completely explained by age, health insurance, pathological characteristics, or treatment received. Black women were also significantly more likely to experience a delay in radiation therapy following BCS. This may indicate barriers to care for DCIS that disproportionately affect Black women in Missouri. The clinical relevance of the observed racial difference in timely initiation of radiation therapy should be addressed. Future studies of disparities in DCIS treatment and outcomes should identify differences in both treatment initiation and completion and other factors that may contribute to the persistent racial difference in IBTs.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Chinwe Madubata was funded by Grant Numbers UL1 TR000448 and TL1 TR000449 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National institutes of Health. Drs Colditz and Liu are supported, in part, by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Dr. Yu is supported by the NIH Surgical Oncology Training Grant 5T32CA9621-27. Dr. Lian is supported, in part, by a Career Development Award from the National Cancer Institute (K07 CA178331). We thank the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, MO., for the use of the Biostatistics Shared Resource. The Siteman Cancer Center is supported in part by an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA091842, Eberlein, PI.

Role of Sponsor: The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The abstract and some data from this manuscript were presented at poster sessions at the 2016 ACTS Translational Science Meeting and the 2016 Siteman Cancer Center Breast Cancer Forum.

Author Contributions: Drs. Liu and Madubata had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Madubata, Liu, Colditz.

Acquisition of data: Yun, Lian, Liu, Colditz.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Madubata, Liu, Goodman, Yun, Yu, Lian, Colditz.

Drafting of the manuscript: Madubata, Liu, Colditz.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual comment: Liu, Colditz, Yun, Madubata, Goodman, Yu, Lian.

Statistical analysis: Liu, Madubata, Lian, Colditz.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: NONE.

References

- 1.Ernster VL, Ballard-Barbash R, Barlow WE, Zheng Y, Weaver DL, Cutter G, Yankaskas BC, Rosenberg R, Carney PA, Kerlikowske K, Taplin SH, Urban N, Geller BM. Detection of ductal carcinoma in situ in women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1546–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.20.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Blair SL, Burstein HJ, Cyr A, Elias AD, Farrar WB, Forero A, Giordano SH, Goldstein LJ, Hayes DF, Hudis CA, Isakoff SJ, Ljung BM, Marcom PK, Mayer IA, McCormick B, Miller RS, Pegram M, Pierce LJ, Reed EC, Salerno KE, Schwartzberg LS, Smith ML, Soliman H, Somlo G, Ward JH, Wolff AC, Zellars R, Shead DA, Kumar R. Breast cancer version 3.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:542–90. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, Brown P, Col NF, Cuzick J, Davidson NE, Decensi A, Fabian C, Ford L, Garber J, Katapodi M, Kramer B, Morrow M, Parker B, Runowicz C, Vogel VG, 3rd, Wade JL, Lippman SM. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2942–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernster VL, Barclay J, Kerlikowske K, Wilkie H, Ballard-Barbash R. Mortality among women with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the population-based surveillance, epidemiology and end results program. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:953–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solin LJ, Fourquet A, Vicini FA, Taylor M, Olivotto IA, Haffty B, Strom EA, Pierce LJ, Marks LB, Bartelink H, McNeese MD, Jhingran A, Wai E, Bijker N, Campana F, Hwang WT. Long-term outcome after breast-conservation treatment with radiation for mammographically detected ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer. 2005;103:1137–46. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson C, Bai H, Neboori H, Takita C, Motwani S, Wright JL, Hobeika G, Haffty BG, Jones T, Goyal S, Moran MS. Multi-institutional experience of ductal carcinoma in situ in black vs white patients treated with breast-conserving surgery and whole breast radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:e279–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virnig BA, Tuttle TM, Shamliyan T, Kane RL. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment, and outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:170–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Colditz GA, Gehlert S, Goodman M. Racial disparities in risk of second breast tumors after ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148:163–73. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3151-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins LC, Achacoso N, Haque R, Nekhlyudov L, Fletcher SW, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Schnitt SJ, Habel LA. Risk factors for non-invasive and invasive local recurrence in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:453–60. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2539-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Innos K, Horn-Ross PL. Risk of second primary breast cancers among women with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:531–40. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9807-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li CI, Malone KE, Saltzman BS, Daling JR. Risk of invasive breast carcinoma among women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ and lobular carcinoma in situ, 1988–2001. Cancer. 2006;106:2104–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stark A, Stapp R, Raghunathan A, Yan X, Kirchner HL, Griggs J, Newman L, Chitale D, Dick A. Disease-free probability after the first primary ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a comparison between African-American and White-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:561–70. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1742-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fedewa SA, Ward EM, Stewart AK, Edge SB. Delays in adjuvant chemotherapy treatment among patients with breast cancer are more likely in African American and Hispanic populations: a national cohort study 2004–2006. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4135–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srokowski TP, Fang S, Duan Z, Buchholz TA, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS, Giordano SH. Completion of adjuvant radiation therapy among women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:22–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman RA, Virgo KS, He Y, Pavluck AL, Winer EP, Ward EM, Keating NL. The association of race/ethnicity, insurance status, and socioeconomic factors with breast cancer care. Cancer. 2011;117:180–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hershman DL, Buono D, McBride RB, Tsai WY, Joseph KA, Grann VR, Jacobson JS. Surgeon characteristics and receipt of adjuvant radiotherapy in women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:199–206. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Punglia RS, Saito AM, Neville BA, Earle CC, Weeks JC. Impact of interval from breast conserving surgery to radiotherapy on local recurrence in older women with breast cancer: retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c845. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nichols HB, Bowles EJ, Islam J, Madziwa L, Sturmer T, Tran DT, Buist DS. Tamoxifen Initiation After Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. Oncologist. 2016;21:134–40. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flanagan MR, Rendi MH, Gadi VK, Calhoun KE, Gow KW, Javid SH. Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Patients with Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: A Population-Based Retrospective Analysis from 2005 to 2012 in the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3264–72. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4668-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson LC, Camacho F, Levine EA, Anderson RT, Stewart JHt. Patterns of care analysis among women with ductal carcinoma in situ in North Carolina. Am J Surg. 2008;195:164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baxter NN, Virnig BA, Durham SB, Tuttle TM. Trends in the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:443–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold HT, Dick AW. Variations in treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ in elderly women. Med Care. 2004;42:267–75. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114915.98256.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haque R, Achacoso NS, Fletcher SW, Nekhlyudov L, Collins LC, Schnitt SJ, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Habel LA. Treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ among patients cared for in large integrated health plans. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:351–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livaudais JC, Hwang ES, Karliner L, Napoles A, Stewart S, Bloom J, Kaplan CP. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:35–42. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailes AA, Kuerer HM, Lari SA, Jones LA, Brewster AM. Impact of race and ethnicity on features and outcome of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer. 2013;119:150–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nassar H, Sharafaldeen B, Visvanathan K, Visscher D. Ductal carcinoma in situ in African American versus Caucasian American women: analysis of clinicopathologic features and outcome. Cancer. 2009;115:3181–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerlikowske K, Molinaro A, Cha I, Ljung BM, Ernster VL, Stewart K, Chew K, Moore DH, 2nd, Waldman F. Characteristics associated with recurrence among women with ductal carcinoma in situ treated by lumpectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1692–702. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang J, Barbera L, Brouwers M, Browman G, Mackillop WJ. Does delay in starting treatment affect the outcomes of radiotherapy? A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:555–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, Buono D, Kershenbaum A, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Gomez SL, Miles S, Neugut AI. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4120–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Yun S, Lian M, Colditz G. Radiation therapy delay and risk of ipsilateral breast tumors in women with ductal carcinoma in situ. [abstract]. Proceedings of the 107th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2016 Apr 16–20; New Orleans, LA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; Cancer Res 2016; 76(14 Suppl): Abstract nr 2576. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith BD, Haffty BG, Buchholz TA, Smith GL, Galusha DH, Bekelman JE, Gross CP. Effectiveness of radiation therapy in older women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1302–10. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]