Abstract

The root bark extract of Aralia taibaiensis is used traditionally for the treatment of diabetes mellitus in China. The total saponin extracted from Aralia Taibaiensis (sAT) has effective combined antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic activities in experimental type 2 diabetic rats. However, the active compounds have not yet been fully investigated. In the present study, we examined effects of twelve triterpenoid saponins on AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation, and found that compound 28-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester (AT12) significantly increased phosphorylation of AMPK and Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). AT12 effectively decreased blood glucose, triglyceride (TG), free fatty acid (FFA) and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) levels in the rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The mechanism by which AT12 activated AMPK was subsequently investigated. Intracellular ATP level and oxygen consumption were significantly reduced by AT12 treatment. The findings suggested AT12 was a novel AMPK activator, and could be useful for the treatment of metabolic diseases.

Keywords: AMPK, Antihyperglycemic activity, Hypolipidemic activity, T2DM, 28-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester (AT12)

INTRODUCTION

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a key target for the treatment of metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes [1]. The activation of AMPK induces increases of glucose uptake, fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis [2]. For decades, the development of AMPK activators from natural products has been reported [2]. Resveratrol is isolated from grapes and has potential for the treatment of diabetic-related disorders through activation of AMPK [3].

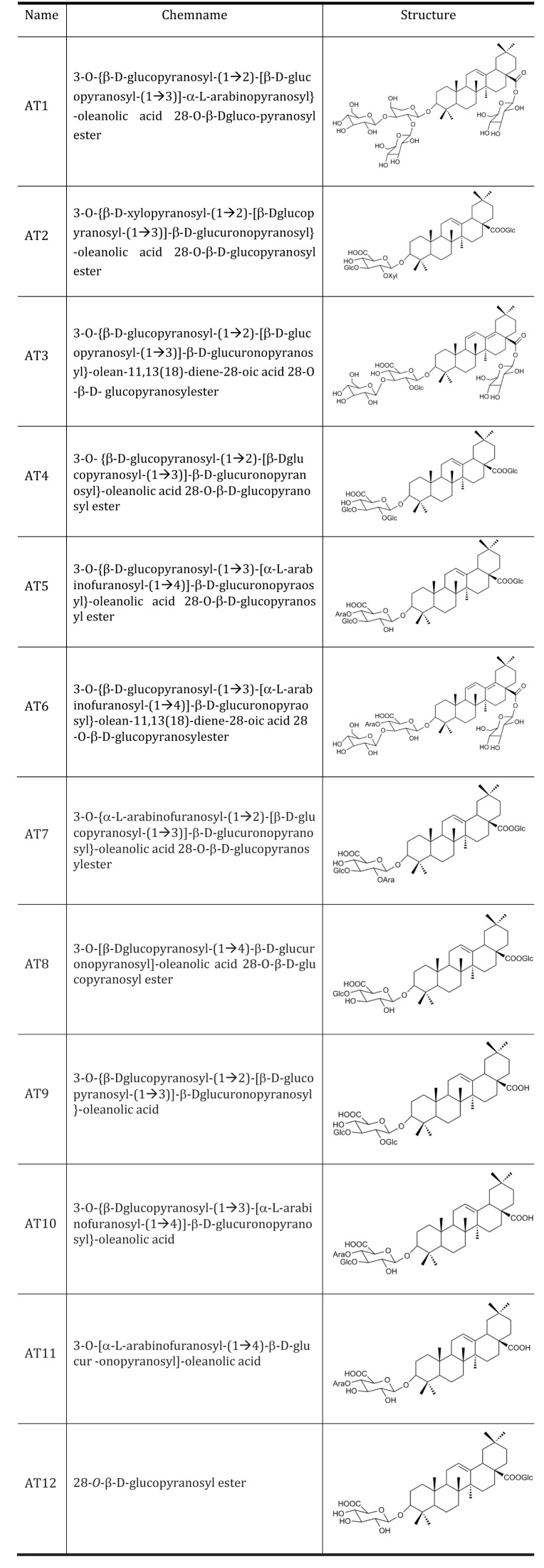

Aralia taibaiensis is a synonym of Aralia stipulate Franch. It is widely distributed in the Qinba Mountains of Western China. The extract of root bark of Aralia taibaiensis has multiple pharmacological activities, including relieving rheumatism, promoting blood circulation to arrest pain, inducing diuresis to reduce edema, and antidiabetic action [4,5]. Over the past decades, many studies had shown the anti-diabetic activities of dietary and medicinal plants were due to the presence of saponins [6,7,8]. The total saponin extracted from Aralia Taibaiensis (sAT) has effective combined antioxidant and antiglycation activities in vitro and ex vivo [4,9]. In addition, sAT dramatically stimulates high-glucose-induced insulin secretion [5]. Recently, sAT is reported to have antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic activities in experimental type 2 diabetic rats [5]. The active components of Aralia taibaiensis are triterpenoid saponins [10,11]. 12 triterpenoid saponins are isolated and their structures are described (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Structures of 12 pure compounds isolated from Aralia Taibaiensis.

The Figure shows structures of 12 pure compounds isolated from Aralia Taibaiensis Ara. Ara, α-L-arabinopyranosyl; Glc, β-D-glucopyranosyl.

In the present study, an attempt is made to identify new AMPK activators from 12 triterpenoid saponins. In addition, we aim to investigate functions of the AMPK activators in preventing type 2 diabetes.

METHODS

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation of the Fourth Military Medical University (Xi'an, China) (ethical permision number: FMMU14005), and carried out in accordance with University Ethics Guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Mature male Wistar Albino rats (8~10 weeks old; 180~220 g) were used in this study and the rats were fed with standard rat pellet diet and water adlibitum.

Induction of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

T2DM was induced in overnight fasted rats by a single intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg of streptozotocin. 120 mg/kg nicotinamide was intraperitoneally administrated after 15 min. Hyperglycemia was confirmed by the elevated glucose levels in plasma, determined at 72 h and on day 7 after STZ injection. The threshold value of fasting plasma glucose to diagnose diabetes was taken as ≥7.0 mM (World Health Organization, 2006). Only rats found with T2DM were used for anti-diabetic study.

Preparation of herbal extracts

The root bark of Aralia taibaiensis Z.Z. Wang et H.C. Zheng was collected in Taibai Mountain, Shaanxi Province of China, and was botanically identified by Dr. Haifeng Tang (vice-professor of Department of Pharmacy, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University). sAT was prepared according to the method described by Tang et al. [10]. Firstly, the dry and powdered root bark (100 g) was extracted three times with 10-fold (v/v) 80% ethanol under reflux for 1 h. Secondly, the alcoholic extracts were concentrated, suspended in distilled water and then partitioned successively with 3-fold (v/v) n-butanol saturated with water for three times. Lastly, the nbutanol extracts were combined and evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 60℃. The yield was 15.91% (w/w). The extract was preserved in a refrigerator for further use.

Determination of total saponins

The content of total saponins in sAT was determined approximately using the following method. To 10ml tubes, 0.05 ml oleanolic acid (1.5 mg/ml), 0.05 ml extract solution (4.0 mg/ml) and 0.05 ml methanol were added. Then, the solvents in each tube were evaporated at 60℃ in a water-bath. The residue was dissolved in 0.2 ml 5% vanillin-glacial acetic acid solution and 0.8 ml perchloric acid. After this, the tubes were transferred to a water-bath at 60℃ for 15 min and quickly cooled in ice water, and 5 ml acetic acid was added to each tube. The absorbance of each solution was measured by spectrophotometry at a maximum absorption wavelength of 554 nm. The content of total saponins in sAT was 90.34%.

Isolation of 28-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester (AT12)

28-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester (AT12) was isolated and identified from total saponin extracted from Aralia Taibaiensis as described previously [4]. The structure of AT12 was elucidated as C42H66O14 by extensive spectral analysis (1H-NMR, 13C-NMR and ESI-MS). The spectral data for AT12 were represented (supplementary Fig. 2).

Experimental design

Rats were randomly grouped. Body weight and food intake were monitored daily during the experimental period. Fasting blood glucose level was monitored from vein every week using an Accu-check blood glucose meter (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The serum free fatty acid (FFA), low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglyceride (TG) levels were determined using a 7180-automatic biochemical analyzer (Hitachi, Japan) at the Department of Clinical Laboratory, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University (Xi'an, China).

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

The oral glucose tolerance test was performed in overnight fasted (18 h) normal rats. Glucose (2 g/kg) was fed 30 min after the administration of drugs. Blood was withdrawn from the retro orbital sinus under ether inhalation at 15, 30, 60 and 120 min of glucose administration. And glucose levels were estimated using glucose oxidase-peroxidase reactive strips and the glucometer (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland).

Cell culture, plasmid and transfection

Mouse C2C12 myoblasts (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin. When cells reached at confluence, the medium was switched to the differentiation medium containing DMEM and 2% horse serum, which was changed every other day.

Antibodies and Reagents

DMEM medium, FBS, L-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin and other cell culture reagents were obtained from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Anti-AMPK antibody, anti-phspho-Thr172 (AMPK) antibody, anti-ACC antibody and anti-phspho-Ser79 (ACC) antibody were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Glibenclamide, streptozotocin and nicotinamide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in M2 buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.6, 0.5% NP-40, 250 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 3 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 20 mM β-glycerol phosphate,1mM sodium vanadate, 1 µg/ml leupeptin). 50 µg of the cell lysates were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% skim milk in PBS/T, the membrane was probed with the relevant antibody and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Biological Industries, BeitHaemek, Israel).

ATP determination

For ATP measurement, a commercially available luciferin-luciferase assay kit was used. Briefly, C2C12 cells were treated with vehicle or AT12 for 2 h. After a single wash with ice-cold PBS, cells were lysed with the somatic cell ATP-releasing reagent provided by the kit. Luciferin substrate and luciferase enzyme were added. Bioluminescence was assessed on a Perkin Elmer 3B spectroflurometer. Whole-cell ATP content was determined by running an internal standard. The cellular ATP level was converted to percentage of vehicle treated cells.

Measurement of oxygen consumption

C2C12 cells (2×105) were divided into aliquots in a BD Oxygen Biosensor System plate (BD Biosciences) in triplicate in the absence or in the presence of AT12. Plates were read on a SAFIRE multimode microplate spectrophotometer at 20 min intervals for 120 min.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean±SD. Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by LSD's test for multiple comparisons. Data analyses were performed by using the SPSS 11.0 software package. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Identification of effective compounds from sAT in modulating glucose and lipid metabolisms

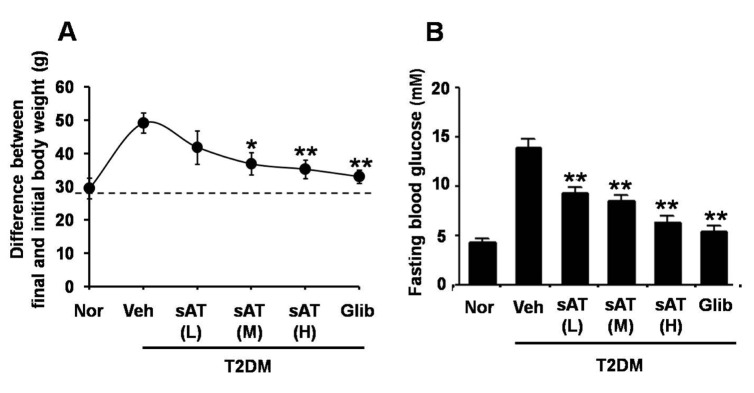

Acute oral toxicity study was firstly performed. None drug-induced physical signs of toxicity were found in rats that were administrated with 2 g/kg sAT. Administration of high dose (300 mg/kg) of sAT showed maximum decreases of body weight and fasting blood glucose level in T2DM rats, which were comparable to glibenclamide (Fig. 2A, B). To elucidate effective compounds, we firstly examined the effects of the 12 pure compounds on AMPK and ACC phosphorylation in C2C12 myocytes. In the results, four compounds (AT4, 10, 11 and 12) exhibited better stimulatory effects on AMPK (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Effects of sAT and the compounds on glucose or lipid metabolism, and AMPK phosphorylation.

STZ induced T2DM rats (n=6) were intragastricly administrated daily with different doses of sAT (L: 75 mg/kg/d; M: 150 mg/kg/d; H: 300 mg/kg/d) and glibenclamide (0.25 mg/kg/d) for 4 weeks. After treatment, all of the rats were fasted overnight. (A) The body weight and (B) fasting blood glucose levels were measured. The data were presented as the mean±SD from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. T2DM rats treated with vehicle alone.

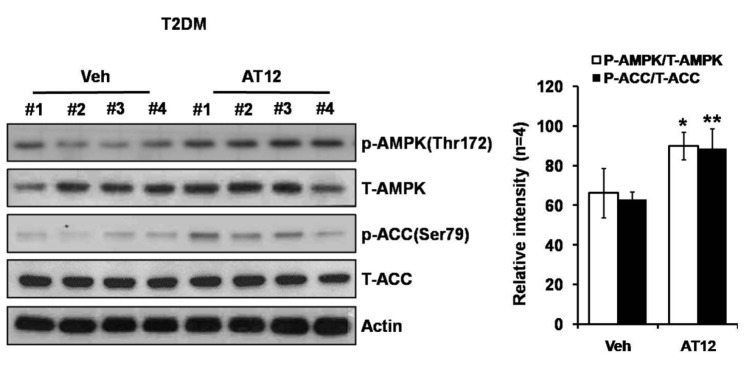

Fig. 3. Effects of 12 triterpenoid saponins on AMPK and ACC phosphorylation.

C2C12 myocytes were treated with 12 species of triterpenoid saponins (1 µg/ml) for 30 min respectively. Whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and then immunoblot was performed using indicated antibodies (top); The phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC were determined and normalized to total (bottom). The data were presented as the mean±SD from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. vehicle.

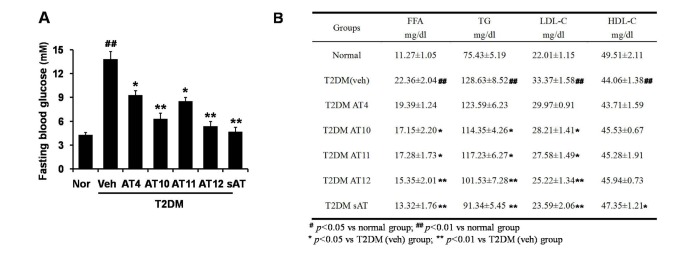

Effects of these effective compounds on blood glucose and lipid levels in experimental type 2 diabetic rats

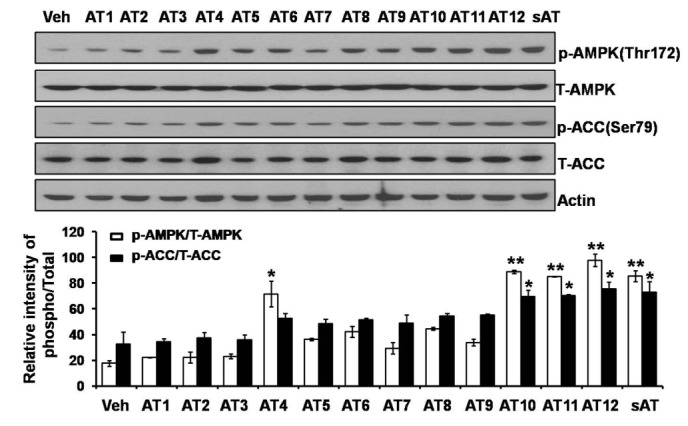

Among the four compounds, administration of high dose of AT12 (300 mg/kg) showed maximum decrease of fasting blood glucose to 61.1%, which was comparable to sAT (66.1%) (Fig. 4A). The serum TG and FFA levels were also significantly decreased by AT12 (Fig. 4B). In addition, AMPK and ACC phosphorylation were increased in the soleus muscles of AT12 and sAT treated T2DM rats (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Effects of four triterpenoid saponins on blood glucose and lipid levels.

(A) T2DM rats (n=6) were intragastricly administrated daily with AT4, AT10, AT11 or AT12 (300 mg/kg/d) respectively for 4 weeks. After treatment, all of the rats were fasted overnight. The fasting blood glucose level was measured; (B) TG and FFA levels in the serum were measured. The data were presented as the mean±SD from three independent experiments. #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. normal rats; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. T2DM rats treated with vehicle alone.

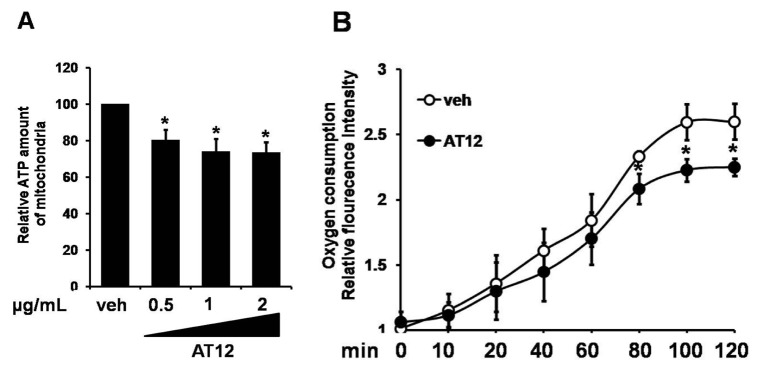

Fig. 5. AT12 increased phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC in skeletal muscle.

Immunoblot of phosphorylated AMPK and ACC levels in the skeletal muscles of T2DM rats and T2DM rats treated with AT12. Relative band intensity was shown. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. T2DM rats treated with vehicle alone.

Mechanism of AT12 mediated AMPK activation

To determine the mechanism by which AT12 activated AMPK, the intracellular ATP level was examined. In C2C12 cells, AT12 caused a concentration-dependent decrease in the intracellular ATP level (Fig. 6A). To investigate whether the changes in the adenosine nucleotides due to the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration, oxygen consumption was examined in the C2C12 myocytes. As shown in Fig. 6B, mitochondrial oxygen consumption was dramatically decreased by treatment of AT12. Therefore, AT12 activated AMPK by decreasing intracellular ATP level through inhibiting mitochondrial respiration.

Fig. 6. AT12 decreased the intracellular ATP level and oxygen consumption.

(A) C2C12 cells were treated with 0.5, 1, 2 µg/ml AT12 for 2 h. Total intracellular ATP levels were measured; (B) Equal volumes of packed C2C12 cells were separated into aliquots in wells of a 96-well BD Oxygen Biosensor plate in the presence of vehicle or 1 µg/ml AT12. The fluorescence in each well was recorded with a SAFIRE multimode microplate spectrophotometer. The data were presented as the mean±SD from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. vehicle.

DISCUSSION

In the study, it was found that AT12, which was isolated from Aralia Taibaiensis, was a newly determined AMPK activator. AT12 significantly decreased fasting blood glucose and lipid levels in T2DM rats. AT12 activated AMPK by decreasing intracellular ATP level through inhibiting mitochondrial respiration.

Pharmacological activation of AMPK improved energy homeostasis in insulin resistant rodents, which made it a therapeutic target in the treatment of type 2 diabetes [12]. It was shown for the first time that AT12 activated AMPK and strongly increased disposal of glucose and lipid from blood in T2DM rats. Though sAT had antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic activities in T2DM rats, little was known about its effective components and molecular mechanisms in regulating glucose and lipid metabolisms. AMPK was a main target of anti-diabetic drugs [13]. In this study, we examined the effects of 12 tritrepenoid saponins that isolated from sAT on AMPK activation. In the results, not all the 12 compounds increased phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC. AT4 and AT10-12 were more effective (Fig. 3). Next, we compared the effects of the four compounds on reducing blood glucose and lipid levels in T2DM rats (Fig. 3A, B). The results strongly indicated that AT12 was more effective than other three compounds and was worthy of being considered as an attractive candidate for the treatment of T2DM.

Skeletal muscle was the main site for glucose disposal and fat catabolism [14]. It was now well established that muscle contraction was a prototypical AMPK activator [15]. Our results clearly demonstrated that AT12 effectively increased phosphorylation of AMPK in skeletal muscle of T2DM rats (Fig. 5). Regulations of energy metabolism through activation of AMPK in response to pharmacological reagents were also observed in extra-muscular tissues, such as adipose tissue and liver. Activation of AMPK inhibited lipolysis and lipogenesis in adipose tissue [16]. Hepatic gluconeogenesis was a major cause of fasting hyperglycemia in diabetic subjects, and fatty liver disease. Disorders of TG, FFA and cholesterol in the liver, were the critical complications of type 2 diabetes [12]. Inhibition of ACC by AMPK led to a decrease in fatty acid synthesis and an increase in fatty acid oxidation, thus reduced serum FFA level and excessive storage of TG (Fig. 2). The findings showed a promising function of AT12 in lipid abnormalities in the liver. Furthermore, the importance of AMPK in the regulation of energy homeostasis provided a potentially widespread function of AT12 in the treatment of a cluster of metabolic disorders. Further detailed testing will be required to elucidate the potential impacts on other insulin-sensitive tissues of AT12.

AMPK agonists elicited or mimicked the effects of contraction (changes in AMP: ATP ratio, intracellular Ca2+ level and reactive oxygen species), and recapitulated some of the exercise-induced adaptations, which were likely to mediate beneficial effects of exercise on insulin sensitivity and glucose transport in skeletal muscle [17,18,19]. In general, a decrease in intracellular ATP activated AMPK concomitant with an increase in AMP [20]. ATP was found to antagonize the effects of AMP on stabilizing phosphorylaiton of AMPK at Thr172 [21]. In C2C12 cells, AT12 caused a concentration-dependent decrease in the intracellular ATP level (Fig. 6A). Some AMPK activators, such as metformin and rosiglitazone, were known to inhibit mitochondrial respiratory [20,22]. On the basis of our results, it was hypothesized that AT12 influenced mitochondrial functions, because these organelles generated most of the intracellular ATP. Oxygen consumption was examined to show whether the changes in the ATP due to the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. As shown in Fig. 6B, mitochondrial oxygen consumption was dramatically decreased by AT12. On the other hand, the primary upstream molecules of AMPK: liver kinase B1 (LKB1) and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-β (CaMKKβ) could activate AMPK [23,24]. Further investigations would be required to determine more mechanisms.

Our study demonstrates that AT12 is a newly determined AMPK activator. Antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic activities of AT12 have been demonstrated in T2DM rats. AT12 regulates glucose and fatty acid metabolism through AMPK-dependent pathways. AT12 activates AMPK through decreasing intracellular ATP level by inhibiting mitochondrial respiration. The findings provide the basis for the future development of AT12 as a new candidate for the management of metabolic disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81201985, 81373947 and 81470174).

Footnotes

Author contributions: Y.L. did the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. M.X. and A.W. reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.C. and N.J. performed the statistical analysis. J.P. and Y.W. contributed to the discussion.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary data including one figure can be found with this article online at http://pdf.medrang.co.kr/paper/pdf/Kjpp/Kjpp021-03-01-s001.pdf.

HPLC analysis of the root bark extract of Aralia Taibaiensis.

1H-NMR, 13C-NMR and ESI-MS spectra of AT12.

References

- 1.Zhang BB, Zhou G, Li C. AMPK: an emerging drug target for diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2009;9:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi Y, Kanbayashi Y, Harata I, Ubagai R, Takimoto T, Suzuki K, Miwa T, Noguchi Y. Petasin activates AMP-activated protein kinase and modulates glucose metabolism. J Nat Prod. 2014;77:1262–1269. doi: 10.1021/np400867m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, Prabhu VV, Allard JS, Lopez-Lluch G, Lewis K, Pistell PJ, Poosala S, Becker KG, Boss O, Gwinn D, Wang M, Ramaswamy S, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG, Lakatta EG, Le Couteur D, Shaw RJ, Navas P, Puigserver P, Ingram DK, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xi M, Hai C, Tang H, Wen A, Chen H, Liu R, Liang X, Chen M. Antioxidant and antiglycation properties of triterpenoid saponins from Aralia taibaiensis traditionally used for treating diabetes mellitus. Redox Rep. 2010;15:20–28. doi: 10.1179/174329210X12650506623041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weng Y, Yu L, Cui J, Zhu YR, Guo C, Wei G, Duan JL, Yin Y, Guan Y, Wang YH, Yang ZF, Xi MM, Wen AD. Antihyperglycemic, hypolipidemic and antioxidant activities of total saponins extracted from Aralia taibaiensis in experimental type 2 diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;152:553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Zaher AO, Salim SY, Assaf MH, Abdel-Hady RH. Antidiabetic activity and toxicity of Zizyphus spina-christi leaves. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee KT, Sohn IC, Kim DH, Choi JW, Kwon SH, Park HJ. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of tectorigenin and kaikasaponin III in the streptozotocin-lnduced diabetic rat and their antioxidant activity in vitro. Arch Pharm Res. 2000;23:461–466. doi: 10.1007/BF02976573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oishi Y, Sakamoto T, Udagawa H, Taniguchi H, Kobayashi-Hattori K, Ozawa Y, Takita T. Inhibition of increases in blood glucose and serum neutral fat by Momordica charantia saponin fraction. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:735–740. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xi M, Hai C, Tang H, Chen M, Fang K, Liang X. Antioxidant and antiglycation properties of total saponins extracted from traditional Chinese medicine used to treat diabetes mellitus. Phytother Res. 2008;22:228–237. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang HF, Yi YH, Wang ZZ, Hu WJ, Li YQ. Studies on the triterpenoid saponins of the root bark of Aralia taibaiensis. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 1996;31:517–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang HF, Yi YH, Wang ZZ, Jiang YP, Li YQ. Oleanolic acid saponins from the root bark of Aralia taibaiensis. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 1997;32:685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buhl ES, Jessen N, Pold R, Ledet T, Flyvbjerg A, Pedersen SB, Pedersen O, Schmitz O, Lund S. Long-term AICAR administration reduces metabolic disturbances and lowers blood pressure in rats displaying features of the insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes. 2002;51:2199–2206. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruderman NB, Carling D, Prentki M, Cacicedo JM. AMPK, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2764–2772. doi: 10.1172/JCI67227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park SY, Kim MH, Ahn JH, Lee SJ, Lee JH, Eum WS, Choi SY, Kwon HY. The Stimulatory effect of essential fatty acids on glucose uptake involves both Akt and AMPK activation in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;18:255–261. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi T, Hirshman MF, Kurth EJ, Winder WW, Goodyear LJ. Evidence for 5' AMP-activated protein kinase mediation of the effect of muscle contraction on glucose transport. Diabetes. 1998;47:1369–1373. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan JE, Brocklehurst KJ, Marley AE, Carey F, Carling D, Beri RK. Inhibition of lipolysis and lipogenesis in isolated rat adipocytes with AICAR, a cell-permeable activator of AMP-activated protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:33–36. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujii N, Hirshman MF, Kane EM, Ho RC, Peter LE, Seifert MM, Goodyear LJ. AMP-activated protein kinase alpha2 activity is not essential for contraction- and hyperosmolarity-induced glucose transport in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39033–39041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narkar VA, Downes M, Yu RT, Embler E, Wang YX, Banayo E, Mihaylova MM, Nelson MC, Zou Y, Juguilon H, Kang H, Shaw RJ, Evans RM. AMPK and PPARdelta agonists are exercise mimetics. Cell. 2008;134:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JE, Choi HC. Losartan inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through activation of amp-activated protein kinase. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;14:299–304. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.5.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carling D, Mayer FV, Sanders MJ, Gamblin SJ. AMP-activated protein kinase: nature's energy sensor. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:512–518. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardie DG, Carling D, Carlson M. The AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinase subfamily: metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:821–855. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunmair B, Staniek K, Gras F, Scharf N, Althaym A, Clara R, Roden M, Gnaiger E, Nohl H, Waldhäusl W, Fürnsinn C. Thiazolidinediones, like metformin, inhibit respiratory complex I: a common mechanism contributing to their antidiabetic actions? Diabetes. 2004;53:1052–1059. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sebbagh M, Olschwang S, Santoni MJ, Borg JP. The LKB1 complex-AMPK pathway: the tree that hides the forest. Fam Cancer. 2011;10:415–424. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9457-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carling D, Sanders MJ, Woods A. The regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by upstream kinases. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(Suppl 4):S55–S59. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HPLC analysis of the root bark extract of Aralia Taibaiensis.

1H-NMR, 13C-NMR and ESI-MS spectra of AT12.