Abstract

Pathological conditions caused by reduced dosage of a gene, such as gene haploinsufficiency, can potentially be reverted by enhancing the expression of the functional allele. In practice, low specificity of therapeutic agents, or their toxicity reduces their clinical applicability. Here, we have used a high throughput screening (HTS) approach to identify molecules capable of increasing the expression of the gene Tbx1, which is involved in one of the most common gene haploinsufficiency syndromes, the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Surprisingly, we found that one of the two compounds identified by the HTS is the vitamin B12. Validation in a mouse model demonstrated that vitamin B12 treatment enhances Tbx1 gene expression and partially rescues the haploinsufficiency phenotype. These results lay the basis for preclinical and clinical studies to establish the effectiveness of this drug in the human syndrome.

Introduction

Gene haploinsufficiency is a common cause of genetic disease. Potential treatment strategies include correcting the dysregulation of critical (pathogenic) genes targeted by the haploinsufficient gene, boosting the expression of the haploinsufficient gene to partially compensate for the reduced gene dosage, and targeting the pathological processes affected by haploinsufficiency. TBX1 gene haploinsufficiency causes most of the clinical features associated with one of the most common segmental aneuploidies in humans, the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) (1,2). The clinical phenotype, which is well recapitulated in Tbx1 mouse mutants, includes congenital anomalies (e.g. heart and vascular defects) as well as adolescence/adult onset features (2,3). The latter is the most suitable to drug therapy, while the former would require diagnosis and treatment during early pregnancy.

To identify potential drugs for correcting the phenotype of Tbx1 mutant mice, we have previously used genetic approaches, but results, albeit significant, have been of difficult practical application (4,5). Here, we have used a different approach that takes advantage of high throughput screening (HTS) to identify molecules capable of enhancing the Tbx1 gene expression in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Surprisingly, we found that vitamin B12 increased expression of Tbx1. Validation in tissue culture using two different cell types confirmed the HTS results and showed that vitamin B12 treatment modifies the epigenetic profile of the gene. In vivo treatment also up regulated Tbx1 gene expression in the haploinsufficient mouse model and ameliorated significantly the haploinsufficiency phenotype in mouse embryos. These findings open a completely new avenue for future studies directed at exploring potential clinical applications for this relatively frequent genetic syndrome using a very well tolerated drug.

Results

High throughput screening for molecules enhancing Tbx1 gene expression

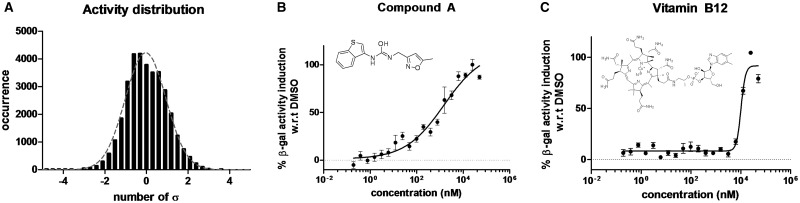

To identify compounds that enhance the expression of Tbx1, we used Tbx1lacZ/+ mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in an HTS assay. In these cells, the expression of Tbx1 can be evaluated using an automatable β-galactosidase assay. We plated these cells in 384-well plates and assayed them against a library of about 35,000 small molecules. The library collection contained a high percentage of drug-like and lead-like molecules, with over 90% of the compounds having a molecular weight below 500 (mean molecular weight is 348 Da) and with cLogP (calculated partition coefficient) and TPSA (total polar surface area) in the range generally accepted as being suitable for orally bioavailable compounds. The average number of rotatable bonds was 5. Screened for diversity by both MACCS166 fingerprints (6) and by methods measuring the maximum common substructure of the central scaffolds, the entire collection clustered into approximately 4500 unique clusters together with over 1000 singleton clusters. The average number of molecules per cluster was around 6. Drugs were used at a concentration of 5 µM, which is the highest possible concentration compatible with a viable DMSO concentration. In addition, due to the absence of a known strong inducer of Tbx1 expression, the HTS was run without a positive control. Therefore, the response to the compounds was calculated as the number of standard deviations from the mean of the whole sample. The distribution of HTS results was found to be grossly normal (Fig. 1A) ; thus the hit threshold was set at 3 standard deviations over the mean. With these criteria, 22 compounds were selected as active (i.e. inducers of Tbx1 expression) and further tested in a dose-response manner, to confirm their activity in the same induction assay. Only two compounds resulted consistently active (Fig. 1B and C). One of the two was vitamin B12, which showed a steep induction and a potency (EC50) of 10 μM. The other compound, hereafter referred to as ‘compound A’ (see Materials and Methods) was found to have an EC50 of 1 μM.

Figure 1.

High throughput screening results. Occurrence distribution of compound screening activity (A). The bin width was set to +3 standard deviations. The grey dotted line represents the best fitted Gaussian distribution. Dose response of the β-gal activity for compound A (B) and vitamin B12 (C). The percentage of induction was calculated with relative to the average DMSO levels (0% induction).

Compound validation

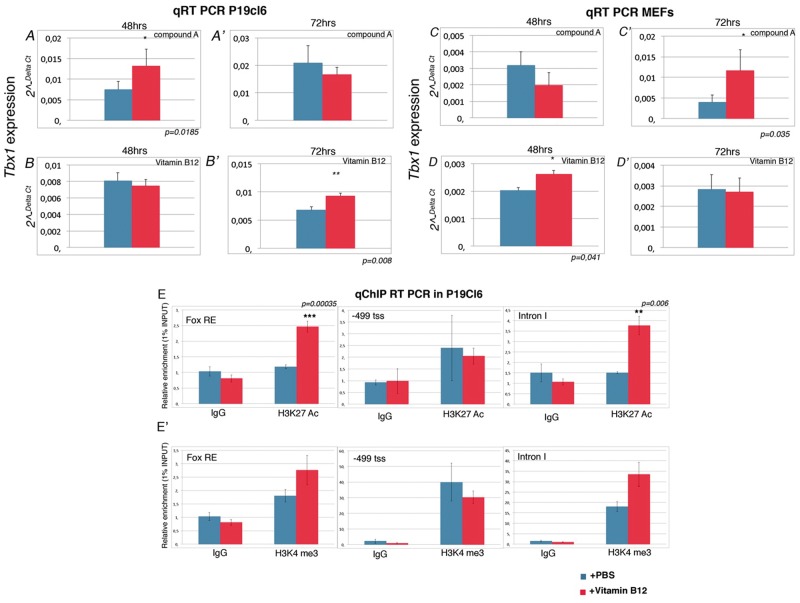

We tested whether vitamin B12 and compound A enhance Tbx1 gene expression in independent cell culture systems. To this end, we used the embryonic carcinoma cell line P19Cl6 (7) and four different MEF clones from WT mouse embryos. Cells were treated with 10μM of vitamin B12 or 1μM of compound A for 48 or 72h., and then RNA was extracted and subjected to quantitative assay (qRT-PCR) to determine the expression of the endogenous Tbx1 gene. In P19Cl6 cells, Tbx1 gene expression increased significantly after 48 h. treatment with compound A (Fig. 2A and A'), while for vitamin B12 treatment, significant up regulation was detected at 72h. (Fig. 2B and B'). In MEF cells, Tbx1 expression increased after 72h. of treatment with compound A (Fig. 2C and C') and after 48h. of treatment with vitamin B12 (Fig. 2D and D'), but at 72h. there was no significant increase (Fig. 2D and D').

Figure 2.

Compound A and vitamin B12 enhance Tbx1 expression in P19Cl6 and MEF cells. (A-D') Quantitative RT-PCR evaluation of Tbx1 expression in P19Cl6 cells treated for 48h and 72h with the compound A (A-A’) and vitamin B12 (B-B’). Quantitative RT-PCR evaluation of Tbx1 expression in MEFs cells treated for 48h and 72h with chemical Compound A (C-C’) and vitamin B12 (D-D’). (E-E') Quantitative ChIP (qChIP) results for three loci, Fox responsive element (FOX-RE) (mm9 chr16:18601587-18601697), promoter (-499 fro transcription start site; mm9 chr16:18587346-18587459), and intron I of Tbx1 gene (mm9 chr16:18587346-18587459). qChIP assays were performed on P19Cl6 cells with and without vitamin B12 treatment. The histograms represent the mean of 6 independent experiments. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Further validation studies were focused on the use of vitamin B12 rather than compound A because the vitamin has a high potential to be quickly translated to the clinic, whereas for compound A there are no chemical characterization nor pharmacological studies.

We asked whether vitamin B12 treatment altered the chromatin state of the Tbx1 gene. To this end, we performed quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qChIP) assays using antibodies to H3K27Ac and H3K4me3, two histone marks that are generally associated with active enhancers or promoters, respectively. We tested for enrichment in three sites of the Tbx1 gene: the upstream enhancer known as the Fox-responding element (FOX-RE) (8–10), the promoter region (-490bp from the transcription start site), and intron 1, which contains a regulatory element (10). The FOX-RE site was not enriched in H3K4me3 and there was no change after treatment. In contrast, H3K27Ac increased significantly at this site after treatment (P = 0.00035). Similarly, at the Intron 1, H3K27Ac enrichment was enhanced by vitamin B12 treatment (P = 0.006). We did not find statistically significant changes with H3K4me3 enrichment (Fig. 2E'), although we found a consistent upward trend in repeated experiments at the Intron 1 site (Fig. 2E', right panel). The two histone modifications at the promoter region did not change in response to treatment (Fig. 2E). Thus, vitamin B12 treatment is associated with H3K27Ac enrichment at regulatory regions, suggesting enhancer activation.

Vitamin B12 treatment partially rescues Tbx1lacZ/+ pharyngeal arch artery anomalies

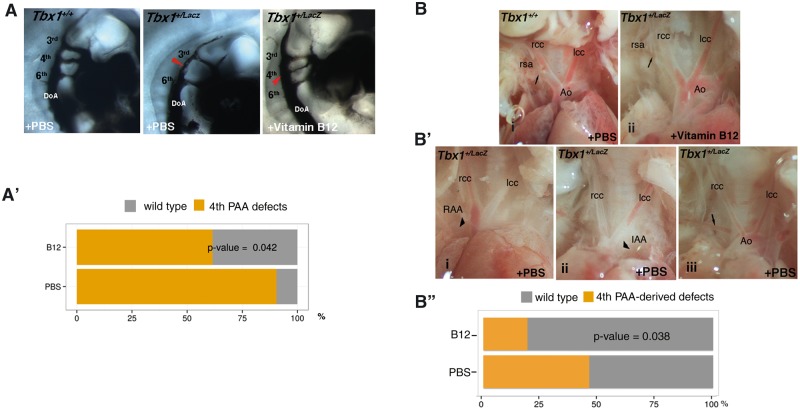

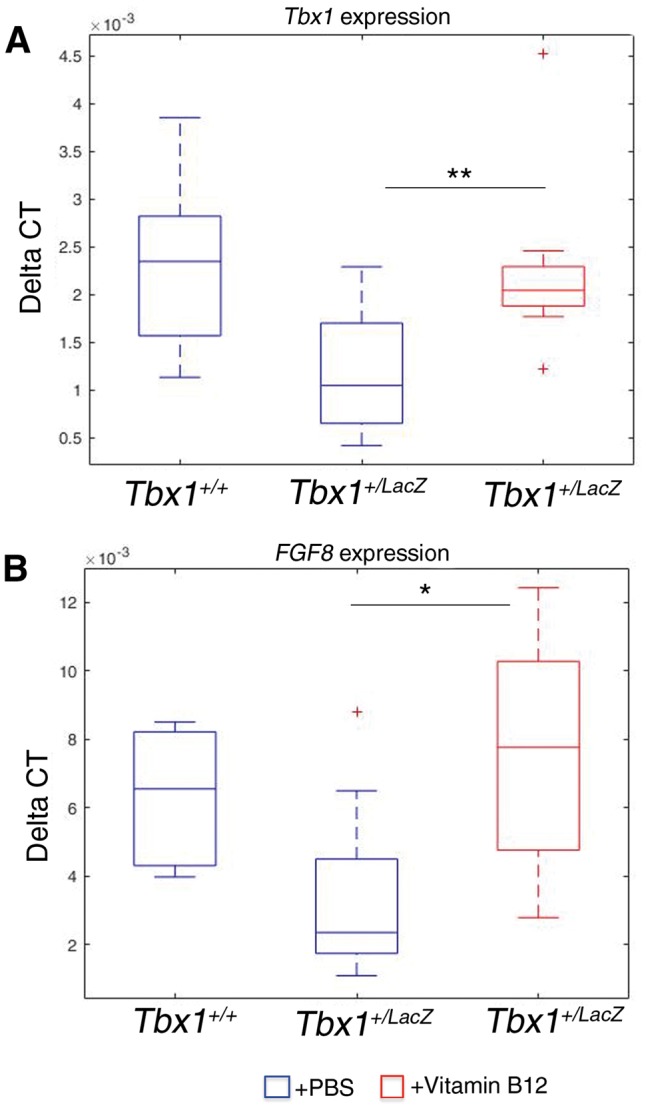

We tested whether vitamin B12 is able to up-regulate Tbx1 expression in mouse embryos in vivo. To this end, we used a mouse model of Tbx1 gene haploinsufficiency, Tbx1lacZ/+ (11). We crossed Tbx1lacZ/+ mice with WT mice and injected intraperitoneally pregnant females with vitamin B12 (or PBS) at E7.5 and E8.5 (2mg/kg body weight, dissolved in PBS (12)). We harvested embryos at E9.5, extracted RNA and performed quantitative real time reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) to evaluate Tbx1 gene expression. Results, demonstrated that vitamin B12-treated Tbx1lacZ/+ embryos had a significantly higher Tbx1 gene expression compared to PBS-treated embryos (P = 0.0045, Fig. 3A). We also tested, in the same embryos, the expression of a Tbx1 target gene known to be involved in the Tbx1 haploinsufficiency phenotype, Fgf8 (9,13,14). Consistently with an increase of Tbx1 expression, we found that Fgf8 is also up-regulated in vitamin B12-treated Tbx1lacZ/+ embryos (P = 0.031, Fig. 3B). Next, we asked whether the effect of vitamin B12 on Tbx1 gene expression could be exploited to modify the Tbx1 mutant phenotype. We crossed Tbx1lacZ/+ mice with WT mice and injected pregnant females with the same dosage of vitamin B12 or PBS at E7.5, E8.5, and E9.5, and we have harvested embryos at E10.5 for phenotypic analysis. Specifically, we have scored the presence of 4th pharyngeal arch artery (PAA) defects that are typical of heterozygous mutants (11,15,16). In PBS-treated embryos, the incidence of 4th PAA defects was 90% (n = 21), while in the treated group it was 61% (n = 26); this is a significant reduction of incidence in the treated group (P = 0.04) (Fig. 4A–A'). To confirm that the observed rescue has a significant impact on the definitive remodelling of the aortic arch later in development, we tested the phenotype at E17.5, when remodelling is complete. For this test, we injected vitamin B12, or PBS, at E7.5, E8.5, E9.5, and E10.5, and harvested fetuses at E17.5. Fetuses were dissected and examined for the presence of 4th PAA-derived anomalies, i.e. aberrant origin of the right subclavian artery, interrupted aortic arch type B, and right aortic arch. Results are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 4B'', examples are shown in Fig. 4B and B'. Overall, the incidence of defects in PBS-treated Tbx1lacZ/+ fetuses was 46% (n = 26), while in the vitamin B12-treated group was 19% (n = 26, P = 0.038). Thus, vitamin B12 has a significant effect on the incidence of anomalies after the remodelling was complete.

Figure 3.

Tbx1 and Fgf8 gene expression is upregulated by vitamin B12 in vivo. Box plots of qRT-PCR evaluation of Tbx1 (A) and Fgf8 (B) gene expression in E9.5 embryos (n = 11 for each point), with or without vitamin B12 treatment. The error bars represent the minimal and maximal values of relative expression. *** P = 0.0045; * P = 0.031.

Figure 4.

Vitamin B12 treatment partially rescues the Tbx1 haploinsufficiency phenotype. (A) Pharyngeal arch arteries of E10.5 embryos visualised by ink injection. Lateral view of PBS-treated WT (left panel), PBS-treated Tbx1lacZ/+ (centre), and vitamin B12-treated Tbx1lacZ/+ (right) embryos. (A’) Graphic representation of the percentage of embryos with 4th PAA defects (PBS sample n = 21; vitamin B12-treated sample n = 26). (B) Representative immages of aortic arch and great vessels of E17.5 fetuses. (i) WT pattern; (ii) normal pattern in a vitamin B12-treated Tbx1lacZ/+ fetus; (B’) Examples of aortic arch patterning defects in Tbx1lacZ/+ fetuses: (i) right aortic arch (RAA), the arrowhead indicates the retropositioned arch; (ii) interrupted arch aortic (IAA) type B, the arrowhead indicates the interruption; (iii) retroesophageal right subclavian artery. Arrows indicate the right subclavian artery. Ao: aorta; lcc: left common carotid artery; rcc: right common carotid artery; rsa: right subclavian artery. (B'') Graphic representation of the percentage of fetuses with aortic arch patterning abnormalities derived from 4th PAA defects (PBS sample n = 26; vitamin B12-treated sample n = 26).

Table 1.

Summary of phenotypic analysis of E17.5 fetuses

| Genotype | Number of fetuses | AbRSA | IAA-B | RAA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | ||||

| Tbx1+/+ | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PBS | ||||

| Tbx1+/+ | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vitamin B12 | ||||

| Tbx1lacZ/+ | 26 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| PBS | ||||

| Tbx1lacZ/+ | 26 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Vitamin B12 |

AbRSA: aberrant origin of the right subclavian artery; IAA-B: interruption of the aortic arch type B (between the left common carotid artery and the ductus arteriosus);. RAA: right aortic arch.

Discussion

We present the results of an HTS study that led to the identification of vitamin B12 as a positive regulator of Tbx1 gene expression. We have validated the results in cultured cells and in vivo, and shown that the vitamin can partially rescue the haploinsufficiency phenotype in a mouse model of 22q11.2DS. The phenotypic anomaly that we measured in our in vivo study is a sensitive indicator of Tbx1 dosage because even a modest reduction of Tbx1 RNA in hypomorphic mutants can induce it (17,18).

Vitamin B12 functions as a cofactor for two enzymes: methylmalonyl CoA mutase, which catalyses the isomerization of methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, and methionine synthase, which catalyses the synthesis of methionine (19), the direct precursor of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). SAM is the general donor of methyl groups for methyltransferase activity, including that involved in epigenetic coding, such as DNA and histone methylation. This mechanism provides a general link between vitamin B12 and gene regulation (20,21). However, how exactly vitamin B12 treatment (at the doses used here) up regulates the Tbx1 gene is not easily explained by a general increase of histone methylation because we did not detect a significant increase in H3K4me3 at the loci tested. We did see significant enhancement of H3K27 acethylation, suggesting that the vitamin is inducing epigenetic changes of the Tbx1 gene. However, we cannot exclude that the partial rescue of the Tbx1 haploinsufficiency phenotype is due to or aided by mechanisms other than Tbx1 up-regulation, for example metabolic changes or expression changes of Tbx1 target genes. Indeed, we have shown an increase of the important target Fgf8 gene. Such increase could be due to Tbx1 up-regulation, but we cannot exclude that it may be due to a direct effect of vitamin B12 on the expression of this gene. Nevertheless, our data open a viable window of opportunity for future treatments of at least some features of the 22q11.2DS.

The clinical presentation of 22q11.2DS is characterized by broad variability, so it would be of interest to test whether there is a link between clinical presentation at birth or after, and vitamin B12 intake during pregnancy, as vitamin B12 is often included in multivitamin complexes recommended as dietary supplements. In addition, genome wide data on 22q11.2DS patients' cohorts (22) could be interrogated for variants of genes related to vitamin B12 pathways, and tested for correlation with phenotypic presentation. Finally, 22q11.2DS is associated with an adolescence/adult onset phenotype, at least some of which appears to be related to Tbx1 haploinsufficiency (3,2). While it is still unclear whether this ‘late’ phenotype also originates from embryonic or fetal damage, it is possible that post-natal treatment might help in preventing the late-onset phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Mouse lines

Animal research was conducted according to EU and Italian regulations. The animal protocol has been approved by the animal welfare committee of the Institute of Genetics and Biophysics (Organismo per il Benessere Animale), protocol 0002183-04062013, and protocol 257/2015-PR of the Italian Ministry of Health. We have used Tbx1lacZ/+ mice (11) bred into the C57/Bl6 strain, to generate heterozygous and wild type embryos. Administration of vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin Sigma-Aldrich Prod. Number V2876) was performed by intraperitoneal injections of pregnant females at embryonic days (E) 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5 (2μg/kg body weight dissolved in PBS, one injection per day). We also injected at E10.5 for the study of phenotype at E17.5. Developmental staging was established by considering the morning in which the vaginal plug was seen as day E0.5. Control mice were injected with the same volume of PBS. To evaluate the impact of vitamin B12 treatment on Tbx1 gene expression, pregnant females were treated at E7.5 and E8.5, and sacrificed at E9.5. Twelve embryos for each genotype, Tbx1lacZ/+ and Tbx1+/+, were collected at E9.5 and RNA isolated as described below.

Statistical methods

Statistical significance of differences between treated and untreated samples was determined by parametric and non-parametric tests. In quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qChIP) assays, significance of fold change differences was assessed using a 2-tailed Student’s t test. Gene expression differences in quantitative real time PCR experiments were evaluated using the two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The rescue of the 4th pharyngeal arch artery defects was tested using the Fisher's exact test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ink injection and phenotype scoring

To visualize the pharyngeal arch arteries (PAAs), Tbx1lacZ/+ and Tbx1+/+, treated and untreated E10.5 embryos were injected intracardially with India ink. Embryos were then dehydrated with 70% EtOH and cleared in 1:2 benzyl benzoate:alcohol benzylic.

The PAA phenotype was scored blind to genotype on cleared embryos under a stereo microscope, by at least two experienced observers. ‘Normal’ vessels were defined as completely patent to ink (from the aortic sac to the dorsal aorta) and with a size comparable to the 3rd and/or 6th PAAs of the same embryo. ‘Defective’ vessels were defined as having one of the following phenotypes: aplasia (no section of it was filled by ink), or hypoplasia (very thin ink filling, often interrupted between the aortic sac and dorsal aorta). Embryos with technically defective injection, i.e. when the aortic sac, 3rd PAA and 6th PAA were not well filled, were discarded.

E17.5 fetuses were dissected and phenotyped by direct observation under the stereo microscope by at least two experienced observers blind to genotype.

Tissue culture experiments

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from WT and Tbx1lacZ/+ (11) mouse E12.5-13 embryos, using standard methods. Briefly, embryo tissue was disaggregated with 0.25% trypsin for 25–30 min at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator, and then resuspended in DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% non essential amino acids, 1U/ml penicillin, 1μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), by pipetting with a 1000µL tip and generate a single cell suspension.

For HTS experiments we used a MEF clone isolated from Tbx1lacZ/+ embryos. This clone, Cl72 after 15-passages showed an immortalized phenotype. For compound, validation, we used independent MEF clones obtained from WT embryos. These clones were used at the second or third passage in tissue culture.

P19Cl6 cells were cultured in alpha-MEM,10% FBS,1% Glutamine, 1U/ml penicillin, 1μg/ml streptomycin. 1.25x105 cells/well were plated and were treated after 24h with 10 µΜ vitamin-B12 and collected at 48 hrs. and 72 h. to RNA isolation and ChIP experiments.

HTS assay

50 nl of test compounds (2 mM solution in DMSO) were transferred to tissue culture-treated, 384-well white plates (Greiner Bio One, Frickenhausen, Germany) by acoustic transfer (EDC biosystems, Milmont, CA, USA). 20 μl of a suspension of 104 Tbx1lacZ/+ MEF cells were added to assay plates. After 48 h incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in humidified atmosphere and 30 min incubation at RT, we added 20 μl/well of Beta Glo (Beta Glo Assay System, Promega). After 1 h incubation at RT, the signal intensity was quantified by the ViewLux uHTS microplate imager (PerkinElmer, USA). Data analysis was performed using the Dotmatics suite (Dotmatics, Bishops Stortford, UK).

‘Compound A’ (1-(benzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-3-((5-methylisoxazol-3-yl)methyl)urea) was purchased from Maybridge (Product Code: HTS12348, ACD Code: MFCD04110438).

The purity of the compound was assessed by UPLC analysis to be 91%. A Waters UPLC system with both diode array detection and electrospray (+’ve and –‘ve ion) MS detection was used. The stationary phase was a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH C18 1.7um 2.1x50mm column. The mobile phase was H2O containing 0.1% formic acid or MeCN containing 0.1% formic acid. Flow rate 0.5 mL/min. Sample concentration: 1 mg/mL. Injection volume 2 μl.

Quantitative gene expression analyses

Total RNA was isolated with TRIZOL (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystem catalog. n. 4368814). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystem). Relative gene expression was evaluated using the 2-ΔΔCt method, and Gapdh expression as normalizer. Primers are Tbx1-F: 5’-CTGACCAA TAACCTG CTG GATGA-3’; Tbx1-R: 5’-GGCTGATATCTGTGCATGGAGTT-3’; FGF8-F: 5'-CAGGTCCTGGCCAACAAG-3'; FGF8-R: 5'-GGTCTC CACA ATGAGCTTCG-3'; GAPDH-F: 5’-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3’; GAPDH-R: 5’-TCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGATG-3’. Expression data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student’s t- test.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

For ChIP assay, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 10 min. The cross-linking reaction was stopped using 0.125 mol/l glycine at room temperature. Cells were lysed and chromatin was sonicated in sharing buffer (0.1%SDS, 15mM Tris pH 7.6, 1mM EDTA) using S2 Covaris System (Duty Cycle: 2%, Intensity: 3, Cycles/Burst: 200, Cycles: 6, Cycles time: 60 s, Temperature: 4 °C). Sonicated chromatin (12 μg for IP) was immunoprecipitated with an anti-H3K4me3 (Millipore) or anti-H3K27 acetylated (Abcam) antibody or Rabbit Control IgG (Abcam). The incubation was performed in sharing buffer containing 0.1%BSA, 1% Triton, 150mM NaCl, 5µg of antibody and preblocked protein A/G coated beads at 4 °C overnight. After incubation, immunoprecipitation, samples were extensively washed with low salt, high salt and LiCl washing solution. The reverse cross-linked was performed in ChIP elution buffer (0.1M NaHCO3 1% SDS) with 0.4 µg/µl of PK. DNA was purified using AM pure beads (Beckman Coulter) and subjected to quantitative PCR amplification.

ChIP primer sequences and genomic location

FOX-RE: genome assembly mm9 cordinates chr16:18601587-18601697. Primers: 5'-TCAGCACAGCCAGCCGCTTT-3' 5'-ATT TCC TTTGGCCCCGCCCC-3'. -499 TSS: chr16:18587346-18587459. Primers: 5'-TTTACGA TTGAAAGGGCAAAG-3' 5'- TTTCTCGGTGTCACTCTCTCC-3'. Intron I: chr16:18586010-18586171. Primers: 5'-GAGAAG GCTTTGCAAACAGG-3' 5'- GCCAGTGCCTGGTTATTTGT-3'.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emanuela Nizi for her technical assistance.

Conflict of Interest statement. Alberto Bresciani, Monica Bisbocci, Alessandra Francone, and Sergio Altamura receive a salary from a private company, IRBM Science Park S.p.A.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the CNCCS Scarl Initiative (to S.A. and A. Ba) and by a grant from the Italian Telethon Foundation GGP14211 (to A. Ba).

References

- 1.Yagi H., Furutani Y., Hamada H., Sasaki T., Asakawa S., Minoshima S., Ichida F., Joo K., Kimura M., Imamura S., et al. (2003) Role of TBX1 in human del22q11.2 syndrome. Lancet, 362, 1366–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paylor R., Glaser B., Mupo A., Ataliotis P., Spencer C., Sobotka A., Sparks C., Choi C.H., Oghalai J., Curran S., et al. (2006) Tbx1 haploinsufficiency is linked to behavioral disorders in mice and humans: implications for 22q11 deletion syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 103, 7729–7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swillen A., McDonald-McGinn D. (2015) Developmental trajectories in 22q11.2 deletion. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet., 169, 172–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitelli F., Lania G., Huynh T., Baldini A. (2010) Partial rescue of the Tbx1 mutant heart phenotype by Fgf8: genetic evidence of impaired tissue response to Fgf8. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol., 49, 836–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caprio C., Baldini A. (2014) p53 suppression partially rescues the mutant phenotype in mouse models of DiGeorge syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 111, 13385–13390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voigt J.H., Bienfait B., Wang S., Nicklaus M.C. (2001) Comparison of the NCI open database with seven large chemical structural databases. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci., 41, 702–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller I., Kobayashi R., Nakajima T., Ishii M., Ogawa K. (2010) Effective and steady differentiation of a clonal derivative of P19CL6 embryonal carcinoma cell line into beating cardiomyocytes. J. Biomed. Biotechnol., 2010, 380561.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamagishi H., Maeda J., Hu T., McAnally J., Conway S.J., Kume T., Meyers E.N., Yamagishi C., Srivastava D. (2003) Tbx1 is regulated by tissue-specific forkhead proteins through a common Sonic hedgehog-responsive enhancer. Genes Dev., 17, 269–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown C.B., Wenning J.M., Lu M.M., Epstein D.J., Meyers E.N., Epstein J.A. (2004) Cre-mediated excision of Fgf8 in the Tbx1 expression domain reveals a critical role for Fgf8 in cardiovascular development in the mouse. Dev. Biol., 267, 190–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z., Baldini A. (2010) Manipulation of endogenous regulatory elements and transgenic analyses of the Tbx1 gene. Mamm. Genome, 21, 556–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsay E.A., Vitelli F., Su H., Morishima M., Huynh T., Pramparo T., Jurecic V., Ogunrinu G., Sutherland H.F., Scambler P.J., et al. (2001) Tbx1 haploinsufficieny in the DiGeorge syndrome region causes aortic arch defects in mice. Nature, 410, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutti E., Lildballe D.L., Kristensen L., Birn H., Nexo E. (2013) Vitamin B12 dependent changes in mouse spinal cord expression of vitamin B12 related proteins and the epidermal growth factor system. Brain Res., 1503, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vitelli F., Taddei I., Morishima M., Meyers E.N., Lindsay E.A., Baldini A. (2002) A genetic link between Tbx1 and Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling. Development, 129, 4605–4611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castellanos R., Xie Q., Zheng D., Cvekl A., Morrow B.E. (2014) Mammalian TBX1 preferentially binds and regulates downstream targets via a tandem T-site repeat. PloS One, 9, e95151.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merscher S., Funke B., Epstein J.A., Heyer J., Puech A., Min Lu M.M., Xavier R.J., Demay M.B., Russell R.G., Factor S., et al. (2001) TBX1 Is Responsible for Cardiovascular Defects in Velo-Cardio-Facial/DiGeorge Syndrome. Cell, 104, 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jerome L.A., Papaioannou V.E. (2001) DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat. Genet., 27, 286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z., Baldini A. (2008) In vivo response to high-resolution variation of Tbx1 mRNA dosage. Hum. Mol. Genet, 17, 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao J., Kochilas L., Nowotschin S., Arnold J.S., Aggarwal V.S., Epstein J.A., Brown M.C., Adams J., Morrow B.E. (2004) Full spectrum of malformations in velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome mouse models by altering Tbx1 dosage. Hum. Mol. Genet., 13, 1577–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shane B., Stokstad E.L. (1985) Vitamin B12-folate interrelationships. Annu. Rev. Nutr., 5, 115–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guéant J.L., Caillerez-Fofou M., Battaglia-Hsu S., Alberto J.M., Freund J.N., Dulluc I., Adjalla C., Maury F., Merle C., Nicolas J.P., et al. (2013) Molecular and cellular effects of vitamin B12 in brain, myocardium and liver through its role as co-factor of methionine synthase. Biochimie, 95, 1033–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mentch S.J., Mehrmohamadi M., Huang L., Liu X., Gupta D., Mattocks D., Gómez Padilla P., Ables G., Bamman M.M., Thalacker-Mercer A.E., et al. (2015) Histone Methylation Dynamics and Gene Regulation Occur through the Sensing of One-Carbon Metabolism. Cell Metab., 22, 861–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo T., Chung J.H., Wang T., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Kates W.R., Hawuła W., Coleman K., Zackai E., Emanuel B.S., Morrow B.E. (2015) Histone Modifier Genes Alter Conotruncal Heart Phenotypes in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 97, 869–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]