Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a major pathogen in chronic lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF) and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (nCFB). Much of our understanding regarding infections in nCFB patients is extrapolated from findings in CF with little direct investigation on the adaptation of P. aeruginosa in nCFB patients. As such, we investigated whether the adaptation of P. aeruginosa was indeed similar between nCFB and CF. From our prospectively collected biobank, we identified 40 nCFB patients who had repeated P. aeruginosa isolates separated by ≥6 months and compared these to a control population of 28 CF patients. A total of 84 nCFB isolates [40 early (defined as the earliest isolate in the biobank) and 41 late (defined as the last available isolate in the biobank)] were compared to 83 CF isolates (39 early and 44 late). We assessed the isolates for protease, lipase and elastase production; mucoid phenotype; swarm and swim motility; biofilm production; and the presence of the lasR mutant phenotype. Overall, we observed phenotypic heterogeneity in both nCFB and CF isolates and found that P. aeruginosa adapted to the nCFB lung environment similarly to the way observed in CF isolates in terms of protease and elastase expression, motility and biofilm formation. However, significant differences between nCFB and CF isolates were observed in lipase expression, which may allude to distinct characteristics found in the lung environment of nCFB patients. We also sought to determine virulence potential over time in nCFB P. aeruginosa isolates and found that virulence decreased over time, similar to CF.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cystic fibrosis, non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis, virulence factors, phenotyping

Introduction

Bronchiectasis is a pathologic diagnosis defined by permanent dilation and widening of the respiratory airways and is common in chronic suppurative lung diseases like cystic fibrosis (CF) and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (nCFB) (Weycker et al., 2005). Patients with bronchiectasis may present with common symptoms including sputum production, recurrent respiratory infections and airway obstruction manifesting in thickened bronchial walls, establishment of chronic infections and increased levels of inflammatory markers (Mhanna et al., 2001; Seitz et al., 2010; Bergin et al., 2013; Gupta et al., 2015). Bronchiectasis arises as a consequence of complications induced by mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator CFTR. However, multiple other non-CFTR mechanisms exist that culminate in bronchiectasis, termed nCFB. Typically considered an ‘orphan disease’, the incidence of nCFB has risen by 8.7 % annually between 2000 and 2007 (Barker & Bardana, 1988; Seitz et al., 2012) and is estimated to cost over $630 million annually in the US healthcare system. Causes of bronchiectasis include immune dysregulation (including autoimmune disorders), obstruction of the airways and complications from infections or injuries (Al-Shirawi et al., 2006; McShane et al., 2012).

In patients with CF and nCFB, accumulation of thick mucus in the lungs and impaired mucociliary clearance allow respiratory infections (Martens et al., 2011). While a myriad of infecting organisms have been identified, the archetypal pathogen of suppurative lung diseases is Pseudomonas aeruginosa (King et al., 2007; Goeminne et al., 2012). During the initial phase of infection, P. aeruginosa is postulated to utilize various virulence factors, including proteases, lipases and elastases, which help to facilitate initial infection (Gillham et al., 2009; Chalmers & Hill, 2013). Following the acute phase, initiation of biofilm formation, increased alginate production, down-regulation of motility genes and attenuation of virulence contribute to the establishment of chronic infections (Harmer et al., 2013; Hogardt & Heesemann, 2013). Chronic P. aeruginosa infections in both nCFB and CF patients have been associated with a decline in respiratory function and an increased risk of morbidity and mortality (Kerem et al., 1990; Evans et al., 1996; Ho et al., 1998; Kosorok et al., 2001; Emerson et al., 2002; Li et al., 2005). However, these trends may not account for the pathogenesis of all isolates of P. aeruginosa. Evidence for phenotypic and genotypic variation within P. aeruginosa isolates suggests that variable adaptation may occur in response to different niches found within the lung environment (Sousa & Pereira, 2014; Foweraker et al., 2005). This variability may extend to virulence factor production and, as a result, may influence the rate of disease progression in individuals with either disease.

Research investigating the pathogenesis of infection within the CF lung has often been extrapolated to nCFB but there is little supporting evidence to enable correlation between the two diseases. Critically, treatments that demonstrate a clinical benefit in CF do not necessarily confer the same benefit in nCFB (O'Donnell et al., 1998; Drobnic et al., 2005; Barker et al., 2014), which suggests that direct extrapolation may not be appropriate. In order to develop strategies to optimally manage chronic P. aeruginosa infections in patients with nCFB, understanding the pathogenesis of chronic P. aeruginosa derived specifically from this patient population is required. We hypothesized that P. aeruginosa would adapt similarly in nCFB patients and CF patients. In this study, we used two longitudinal sets of P. aeruginosa isolates, one from nCFB patients and the other one from CF patients, to examine virulence factor production of isolates from the two cohorts. In addition, we set out to observe whether the attenuation of virulence traits occurs over time, akin to that observed in CF (Lorè et al., 2012).

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

P. aeruginosa isolates were collected from patients attending the Calgary Adult Cystic Fibrosis Clinic and the Calgary Bronchiectasis Clinic from 1986 to 2013. The Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board E-23087 granted permission for the collection and analysis of these strains. P. aeruginosa was identified from routine sputum samples submitted for semi-quantitative sputum evaluation during regular clinical visits and was prospectively inventoried and stored at −80 °C in the Calgary Adult CF Clinic Biobank (Parkins et al., 2014). We retrospectively audited the biobank to identify adults with nCFB who were repeatedly positive for P. aeruginosa for more than 6 months. This biobank included every isolate from every clinical encounter for individuals with CF and serial but not comprehensively collected isolates for individuals with nCFB. Every morphologically distinct colony type identified on MacConkey agar identified at each of two distinct time points was included: early (defined as the earliest available P. aeruginosa isolate identified in the biobank) and late (defined as the most recent isolate available in the biobank). These were compared to a selection of P. aeruginosa derived from adults with CF who had chronic infection spanning >6 months.

Each isolate was cultured in tryptic soy broth and incubated overnight at 37 °C prior to use in each assay, which was conducted in three triplicate replicates (n=9) unless otherwise stated. For the protease, lipase and elastase assays, each culture was normalized to an OD600 of 0.3 and spotted in triplicate on each plate.

Protease.

Protease production was assayed as previously described using dialysed BHI agar plates (Sokol et al., 1979). Protease activity was quantified by measurement of the zone of clearance after incubation for 24 h at 37 °C.

Lipase.

Lipase plates were prepared as described by Lonon et al. (1988), containing 1 % (w/v) of bactopeptone, 0.5 % (w/v) of sodium chloride, 0.01 % (w/v) of calcium chloride, 1.5 % (w/v) of noble agar and 1 % (w/v) of Tween 80. Lipase activity was measured by the cloudiness around the cells after 48 h incubation at 37 °C.

Reverse elastase.

Elastase expression was measured through the breakdown of elastin as described by Rust et al. (1994). Agar containing 0.8 % (w/v) nutrient broth and 2 % (w/v) noble agar was dissolved in distilled water and was pH-adjusted to 7.5. This composed the bottom layer of the plate. An elastin preparation containing 0.8 % (w/v) nutrient broth, 2 % (w/v) noble agar and 0.5 % (w/v) elastin was then overlaid onto the medium. The resulting zone of clearance was measured after 24 h incubation at 37 °C followed by 48 h at 4 °C.

Swim and swarm motility.

Swim motility was assessed by using 0.3 % LB agar plates as performed by Murray & Kazmierczak (2006) and was measured by the distance travelled from the point of inoculation after an incubation period of 72 h at 22 °C with extra humidity.

Swarm plates were prepared according to Kohler et al. (2000) using M8 medium supplemented with 0.2 % (w/v) glucose, 0.05 % (w/v) glutamate, 0.5 % (w/v) noble agar and 0.024 % (w/v) MgSO4. The radial distance of swarming for each isolate was then recorded after incubation for 48 h at 37 °C.

Biofilm assay.

Each culture was normalized to an OD600 of 0.001 in tryptic soy broth and inoculated in triplicate into two Calgary Biofilm Devices (CBDs) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and assessed with two complementary assays: the biofilm biomass assay and viable cell count assay adapted from a protocol by Ceri et al. (1999).

Biofilm biomass assay.

Biomass production was quantified using the crystal violet assay. After incubation, the CBD lid, which contained 96 pegs, was washed with sterile water, allowed to dry and then stained with 1 % crystal violet followed by three consecutive washes with PBS. The lid was then decolorized in another 96-well plate containing methanol and the absorbance was recorded at an optical density of 540 nm in a Perkin Elmer Victor X4 plate reader.

Viable cell count assay.

After incubation for 24 h, the CBD lid was placed into a 96-well plate containing 0.85 % saline and sonicated (5510 Branson) for 10 min. Tenfold serial dilutions were then carried out and 20 µl of each dilution for each isolate was spotted on a tryptic soy agar plate and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The numbers of colonies were counted as a measure of viable cells in the biofilm.

Mucoidy.

The mucoid phenotype was qualitatively assessed by a slimy appearance on Pseudomonas Isolation Agar after incubation for 48 h at 37 °C.

Phenotypic identification of LasR mutants.

LasR mutants were identified by growth at 37 °C after incubation for 48 h on M9 medium supplemented with 0.1 % (w/v) adenosine and 1.5 % (w/v) noble agar as done previously (Sandoz et al., 2007).

Mutation frequency determination.

Mutation frequency was determined using a rifampicin screen described by Oliver et al. (2000). Strains were considered hypermutators if their mutation frequency was found to be 20-fold greater than that of our control strain PAO1.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad). Column statistics allowed the calculation of the mean value of the three triplicate trials (n=9) of each isolate for the protease, lipase, elastase, swarm and swim motility, biofilm, mucoidy and LasR assays. Using a P value <0.05 for significance, we used the nonparametric, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test to compare the phenotypic assays between our nCFB and CF cohorts. Similarly, we also used the Mann–Whitney U test to analyse the phenotypic assays between the two reference points (early and late) in our nCFB cohort. For dichotomous variables, we used a combination of Fisher's exact test and chi-squared test (α<0.05) to determine whether significant differences existed in our cohorts with respect to the LasR, mucoidy and hypermutator assays.

Hierarchal clustering analysis.

Phenotypic clustering of virulence factors was done through the use of cluster 3.0 (Stanford University) using the unweighted pair group method. The dendrogram was generated based on criteria set by Duong et al. (2015) and visualized using Java TreeView (Saldanha, 2004).

Results

Forty patients with nCFB, meeting inclusion criteria of repeated P. aeruginosa isolation spanning >6 months were identified. From these patients, we selected 81 isolates to study: 40 early isolates and 41 late isolates. The median time between early and late isolate collection for patients was 3.16 years (range: 0.5–21.4 years). Our CF control cohort was derived from 28 patients chosen randomly from a collection of patients known to be infected with both unique and epidemic strains and included 39 early and 44 late isolates (Duong et al., 2015). The median time between early and late CF isolates collected was 14 years (range: 2–24 years).

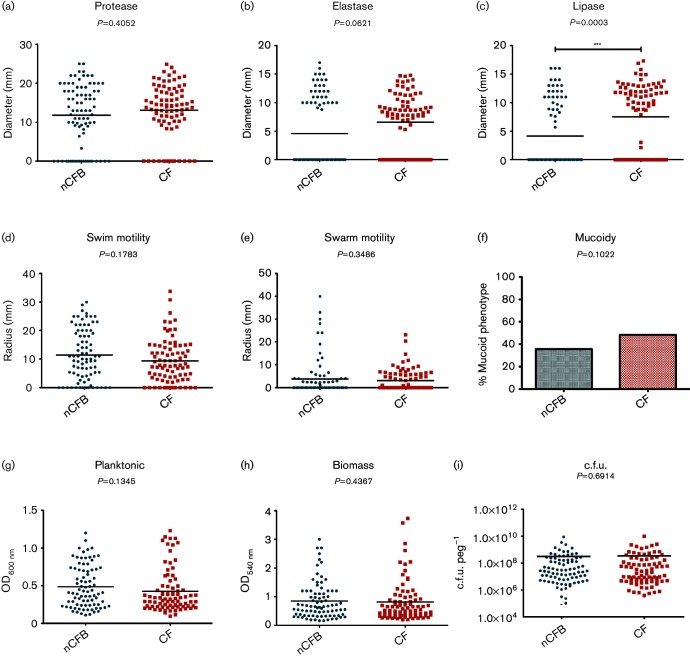

Comparison of phenotypic traits in P. aeruginosa isolated from patients with CF and nCFB

We first wanted to determine how P. aeruginosa phenotypically adapts to the environment of the bronchiectatic lung environment. In order to do so, we compared the variation in expression of a number of phenotypic traits between CF and nCFB isolates. Overall, we observed a diverse range of expression for each phenotype assessed in P. aeruginosa isolates from both nCFB and CF (Fig. 1). When the virulence factor production was compared between our nCFB and CF isolates, we found that the overall distribution was heterogeneous. Furthermore, no significant differences were found between nCFB and CF isolates based on the medians of protease and elastase production, swim and swarm motility, mucoidy or biofilm growth (Fig. 1a, b, d–i).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of P. aeruginosa isolates between nCFB (n=84) and CF (n=83) isolates. Isolates were characterized for protease (a), elastase (b) and lipase (c) production; swim (d) and swarm (e) motility; mucoidy (f); planktonic growth (g); biomass production (h); and viable cell count in biofilm (i). Black horizontal bars represent the mean of each group. Statistical analysis of median was determined to be significant if P<0.05.

On the other hand, isolates derived from individuals with nCFB were found to exhibit significantly lower levels of lipase activity (P=0.0003) compared to CF isolates (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, in terms of isolates that do not produce lipase, we found that the nCFB cohort had significantly more lipase-null isolates [53/84 (63 %)] as compared to CF isolates [29/83 (35 %)] (P=0.0003). Likewise, we observed a significantly higher proportion of non-elastase-producing isolates [51/84 (61 %)] in the nCFB isolates as compared to 27/83 (33 %) isolated from patients with CF (P=0.0003) (Fig. 1c), suggesting that differences in the elastase- and lipase-null isolates exist between the two patient cohorts. Furthermore, as lipase and elastase production are both regulated by the Las/Rhl quorum sensing systems (Rust et al., 1996; Reimmann et al., 1997), we sought to examine the proportion of LasR mutant phenotype isolates that also were null for elastase and lipase activity. As LasR mutants are deficient in nucleoside hydrolase (Nuh) activity, they are unable to grow on adenosine as their sole carbon source (Heurlier et al., 2005). In total, we found 34/51 (67 %) of non-elastase-producing nCFB isolates and 26/53 (49 %) of lipase-null isolates were positive for the LasR mutant phenotype.

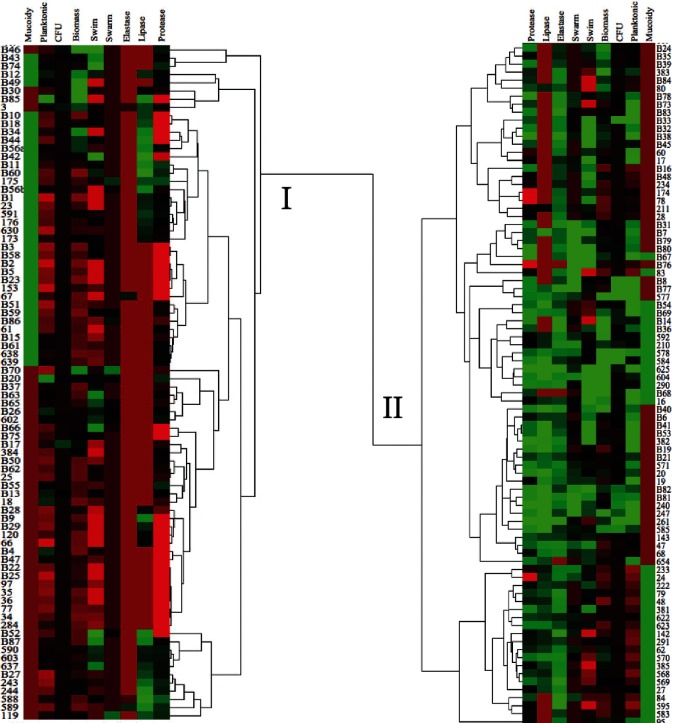

Hierarchical clustering of phenotypic traits from nCFB and CF isolates

Fig. 1 demonstrates that the distribution and means of individual traits were similar with only lipase being significantly different. However, to enable a more comprehensive assessment of phenotypes, we examined the entire set of traits for each isolate by clustering the isolates from both nCFB and CF isolates. The isolates clustered into two large clades, referred to as clade I and clade II (Fig. 2). Clade I had a total number of 82 isolates, with 50 (61 %) nCFB and 32 (39 %) CF isolates. Conversely, a total of 85 isolates in clade II consisted of 34 (40 %) nCFB and 51 (60 %) CF isolates (Fig. 2). A comparison between the two clades for the distribution of nCFB and CF isolates within each clade was found to be significantly different (P=0.0067) suggesting that nCFB isolates dominated clade I and CF isolates dominated clade II.

Fig. 2.

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of phenotypic traits for nCFB and CF isolates (n=167) splits into clades I (upper) and II (lower). Average expression in each assay is represented by the black colour. Isolates with above average expression are shown in green while isolates below average are in red. nCFB isolates are all indicated by a capital B. cluster 3.0 and Java TreeView were used to build this cluster dendrogram.

Knowing this distribution, we then assessed whether virulence factor production was different in each clade. Overall, we found that the clades separated by relative levels of virulence factor production (Fig. 2). P. aeruginosa isolates found in clade I (consisting mainly of nCFB-derived isolates) showed lower levels of virulence expression (protease, elastase and lipase), swim and swarm motility and biofilm formation relative to isolates found in clade II (consisting mainly of CF-derived isolates). In addition to the relatively low levels of virulence expression, we also found a larger abundance of elastase-null and lipase-null isolates within clade I. Conversely, we found that the majority of clade II isolates had above average elastase and lipase production.

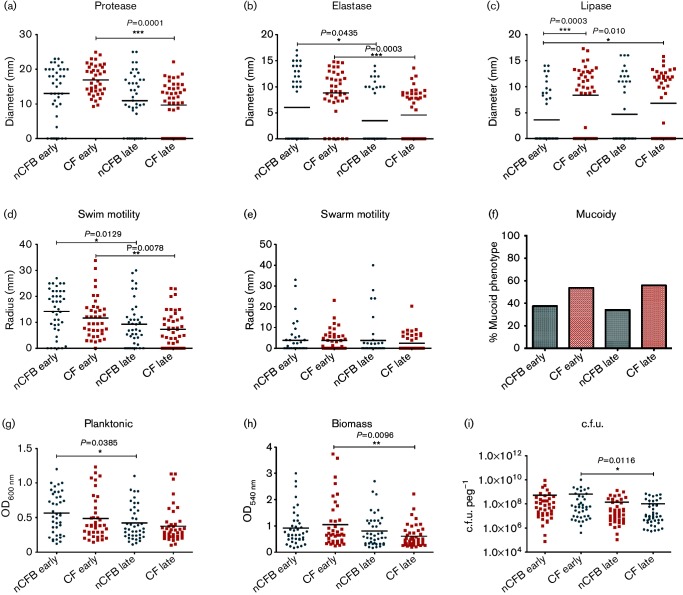

Early and late expression of virulence factors in nCFB isolates

We compared P. aeruginosa in the nCFB subset taken at different time points to investigate whether attenuation of virulence occurred over time as has been observed in CF isolates (Lorè et al., 2012). Accordingly, we observed a significant decrease in protease, elastase, swim motility, biomass and viable cell count between early and late in our CF cohort (Fig. 3). However, we did not observe significant differences with respect to the production of protease, lipase or mucoidy assays in our nCFB cohort. Furthermore, when we evaluated the LasR mutant phenotype, we found that the 18/40 (45 %) of early isolates and 25/41 (61 %) of our late isolates were positive for mutant phenotype (data not shown). However, we did observe a significant decline in elastase expression (P=0.0435) between early and late isolates (Fig. 3b). Similarly, while swarm motility did not differ, we observed a reduction in swim motility between both reference points (Fig. 3d). With respect to biofilm growth, we found that the biofilm capabilities remained similar between early and cohorts. However, planktonic growth was observed to be reduced (P=0.0385) in late nCFB isolates (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, we sought to investigate the proportion of hypermutator strains in a small subset of 20 nCFB isolates and observed no significant differences between early (3/10) and late (5/10) isolates.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of P. aeruginosa isolates from nCFB at early (n=40) and late (n=41) reference points to early (n=39) and late (n=44) CF isolates. Isolates were characterized for protease (a), elastase (b) and lipase (c) production; swim (d) and swarm (e) motility; mucoidy (f); planktonic growth (g); biomass production (h); and viable cell count in biofilm (i). Black horizontal bars represent the mean of each group. The median distribution was considered significant at P<0.05.

Discussion

P. aeruginosa isolated from nCFB patients has both similarities and distinct differences in virulence factor production when compared to CF isolates

While the a etiology of nCFB and CF are markedly different, we found that P. aeruginosa derived from nCFB patients display similar adaptation strategies compared to those isolates from CF. Critically, we observed a substantial degree of phenotypic heterogeneity among all the P. aeruginosa isolates examined in this study. As the assumption of phenotypic diversity of P. aeruginosa has previously been demonstrated in CF (Workentine et al., 2013; Clark et al., 2015), it appears that phenotypic diversity is also evident within our cohort of nCFB isolates. The broad range of virulence potential in our cohort is likely due to the extensive genome plasticity found within P. aeruginosa, which influences the adaptation strategies of P. aeruginosa to these unique lung microenvironments (Shen et al., 2006). The capability of these isolates to colonize these unique niches may play a role in influencing the levels of virulence and survival of P. aeruginosa (Mathee et al., 2008).

Furthermore, we observed a high degree of similarity of virulence factor production, motility and biofilm formation. The expression of these virulence traits is likely influenced by the lung environment and has been suggested to be important in the colonization by P. aeruginosa (Cowell et al., 2003; Tingpej et al., 2007; Gellatly et al., 2012). The similar levels of protease and elastase expression, swim and swarm motility and biofilm formation suggest that these virulence traits play a similar role in the adaptation strategy of P. aeruginosa during the initial colonization of individuals with nCFB to that in CF (Drake & Montie, 1988; O'Toole & Kolter, 1998). In particular, biofilms have been documented within the lungs of individuals with CF (Singh et al., 2000) and adaption to the biofilm mode of growth is thought to be a critical factor in the persistence and resistance to both the immune system and exogenous antibiotics (Drenkard & Ausubel, 2002; Mah et al., 2003). In concordance with findings by Perez et al. (2013), similar levels of biofilm characteristics between our patient cohorts in our study support the important role of biofilm formation in both nCFB and CF.

While we found many phenotypic similarities between P. aeruginosa isolates from both groups, we also observed distinct differences between both diseases. For instance, we observed a higher proportion of elastase-null nCFB isolates relative to our CF isolates. Elastase plays a role in host tissue invasion, immune evasion and tight junction disruption and is under the control of the LasIR quorum sensing system (Cowell et al., 2003; Kuang et al., 2011; Nomura et al., 2014). As LasR is a positive regulator of lasB (gene encoding elastase), mutations in the lasR would result in a non-elastase-producing isolate, which has been shown to provide a selective growth advantage on carbon and nitrogen sources, including amino acids (Gambello & Iglewski, 1991; Luján et al., 2007; D'Argenio et al., 2007). As we found a high proportion or elastase-null isolates with the LasR mutant phenotype, we suspect that mutations in lasR may also be an important factor in the adaptation of P. aeruginosa to the nCFB lung environment.

One notable distinction observed in our study is the markedly lower lipase expression found in our nCFB cohort. Bacterial lipases, including those secreted by P. aeruginosa, contribute to pathogenesis by breaking down the lipid component of lung surfactants to provide free fatty acids for growth and allow direct targeting of the host membrane (Lonon et al., 1988; Barth & Pitt, 1996; Gellatly et al., 2012). The breakdown of fatty acids required for beta-oxidation likely serves as an important source of carbon and nitrogen for growth (Barth & Pitt, 1996; Kang et al., 2008). The lungs of individuals with CF have been observed to have higher levels of total phospholipids relative to those with chronic bronchiectasis (Girod et al., 1992; Puchelle et al., 2002) which we suspect contributes to the differential levels of lipase expression observed between our patient cohorts.

Expression of virulence factors by P. aeruginosa generally decreases over time in nCFB

The dogma in CF research is that, over time, there is a reduction in virulence in P. aeruginosa (Lorè et al., 2012). This has not previously been reported in nCFB – but presumed. Within our study, we observed a trend towards decreased virulence factor production over time and, in particular, observed a significant decrease in elastase production and swim motility. We suspect that our findings are likely due to environmental pressures which select against elastase expression over the course of infection in individuals with suppurative lung diseases (Smith et al., 2006). The decrease in swim motility was likely due to the transcriptional down-regulation of motility-related genes and the establishment of biofilms, which are considered a hallmark of chronic infections in both CF and nCFB (Déziel et al., 2001; Hogardt & Heesemann, 2013; Varga et al., 2015).

Interestingly, we also found that the proportion of mucoid and lasR mutant phenotypes of P. aeruginosa isolates did not change between the early and late nCFB isolates. The acquisition of lasR− and mucoid phenotypes has been shown to be an adaptation strategy to the lung environment and may be an indicator of disproportionate disease progression in CF (Li et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2006; Hoffman et al., 2009; LaFayette et al., 2015). As such, our findings suggest that this may not be as common in nCFB and provide an interesting distinction between the two diseases. Taken altogether, it is possible that the different inflammatory environment of nCFB may place a smaller pressure on P. aeruginosa to acquire a mucoid phenotype and lasR mutations over time (Bergin et al., 2013).

An important limitation in this work is the retrospective nature of our study. As the isolates tested were obtained for the biobank upon clinic visit, it is uncertain how long or at what stage the patients presented with the disease prior to collection of the sputum. Rather than ‘early’ and ‘late’, we might be comparing ‘late’ and ‘later’ isolates – isolates that may have previously already undergone reduction in expression. Indeed, the presentation of nCFB is insidious, with 30–40 years passing between the onset of symptoms and a clinical diagnosis, time in which infections can develop and evolve (Pasteur et al., 2000; King et al., 2006). Accordingly, any longitudinal cohort study following nCFB patients for infections and changes in virulence potential is going to be subject to the same age-related limitations as our own, something not observed in CF cohorts where historically 75 % of patients were diagnosed before age 2 years (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2015). Furthermore, heterogeneity within chronically infecting populations of P. aeruginosa has now been established in both nCFB and CF (Gillham et al., 2009; Workentine et al., 2013). While we sampled a large number of isolates, our sampling included only a small number from each individual patient and therefore might not have adequately represented the phenotypic diversity. Lastly, differences in antibiotic therapy between patients with nCFB and CF may influence the differences in the phenotypic adaptation observed within our study.

In conclusion, the importance of P. aeruginosa in employing various strategies of colonizing the CF lung has been extensively investigated (Foweraker et al., 2005; Hogardt & Heesemann, 2013). However, this relationship has been largely unexplored in the case of nCFB with many conclusions inferred from pre-existing CF research. As such, the aim of our study was to address this current gap of knowledge with respect to the adaptation of P. aeruginosa in nCFB. Indeed, we found similar adaptation strategies between isolates of P. aeruginosa from nCFB patients – which, due to the broad range of environmental niches, display a wide spectrum of virulence and motility (Pujana et al., 1999; Penesyan et al., 2015). While differences in airway characteristics exist between CF and nCFB, we have found that P. aeruginosa largely adapts in a similar manner, extending from virulence factor production to motility and biofilm formation, and that virulence tends to decrease over time. These adaptations may be influenced by differences in mucus viscosity, ciliary clearance and anoxic environments, as well as host responses. We have provided evidence suggesting that differential levels of lipase expression exist between nCFB and CF and may further influence the adaptation of P. aeruginosa in response to the unique characteristics of each lung environment. Overall, this study has established that, with a few exceptions owing to fundamental differences between the disease processes, P. aeruginosa causing chronic infection in patients with nCFB undergo phenotypic adaption similar to that observed for isolates derived from individuals with CF.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the Lung Association of Alberta and Northwest Territories to M. D. P. and D. G. S. and a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN 203595-2013) to D. G. S. T. E. W. was supported by a scholarship from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Alberta Innovates Technology Futures and J. D. was supported by QEII scholarships.

Abbreviations:

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- nCFB

non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis

References

- Al-Shirawi N., Al-Jahdall H., Al Shimemeri A.(2006). Pathogenesis, etiology and treatment of bronchiectasis. Ann Thorac Med 141–51. [Google Scholar]

- Barker A. F., Bardana E. J.(1988). Bronchiectasis: update of an orphan disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 137969–978. 10.1164/ajrccm/137.4.969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker A. F., O'Donnell A. E., Flume P., Thompson P. J., Ruzi J. D., de Gracia J., Boersma W. G., De Soyza A., Shao L., et al. (2014). Aztreonam for inhalation solution in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (AIR-BX1 and AIR-BX2): two randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med 2738–749. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70165-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A. L., Pitt T. L.(1996). The high amino-acid content of sputum from cystic fibrosis patients promotes growth of auxotrophic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol 45110–119. 10.1099/00222615-45-2-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergin D. A., Hurley K., Mehta A., Cox S., Ryan D., O'Neill S. J., Reeves E. P., McElvaney N. G.(2013). Airway inflammatory markers in individuals with cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. J Inflamm Res 61–11. 10.2147/JIR.S40081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceri H., Olson M. E., Stremick C., Read R. R., Morck D., Buret A.(1999). The Calgary Biofilm Device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J Clin Microbiol 371771–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers J. D., Hill A. T.(2013). Mechanisms of immune dysfunction and bacterial persistence in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Mol Immunol 5527–34. 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S. T., Diaz Caballero J., Cheang M., Coburn B., Wang P. W., Donaldson S. L., Zhang Y., Liu M., Keshavjee S., et al. (2015). Phenotypic diversity within a Pseudomonas aeruginosa population infecting an adult with cystic fibrosis. Sci Rep 510932. 10.1038/srep10932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell B. A., Twining S. S., Hobden J. A., Kwong M. S., Fleiszig S. M.(2003). Mutation of lasA and lasB reduces Pseudomonas aeruginosa invasion of epithelial cells. Microbiology 1492291–2299. 10.1099/mic.0.26280-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (2015). Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry 2014 Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD. https://www.cff.org/Our-Research/CF-Patient-Registry/Highlights-of-the-2014-Patient-Registry-Data/. [Google Scholar]

- D'Argenio D. A., Wu M., Hoffman L. R., Kulasekara H. D., Déziel E., Smith E. E., Nguyen H., Ernst R. K., Larson Freeman T. J., et al. (2007). Growth phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants adapted to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Mol Microbiol 64512–533. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05678.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déziel E., Comeau Y., Villemur R.(2001). Initiation of biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 57RP correlates with emergence of hyperpiliated and highly adherent phenotypic variants deficient in swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities. J Bacteriol 1831195–1204. 10.1128/JB.183.4.1195-1204.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake D., Montie T. C.(1988). Flagella, motility and invasive virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Gen Microbiol 13443–52. 10.1099/00221287-134-1-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenkard E., Ausubel F. M.(2002). Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature 416740–743. 10.1038/416740a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobnic M. E., Suñé P., Montoro J. B., Ferrer A., Orriols R.(2005). Inhaled tobramycin in non-cystic fibrosis patients with bronchiectasis and chronic bronchial infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann Pharmacother 3939–44. 10.1345/aph.1E099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong J., Booth S. C., McCartney N. K., Rabin H. R., Parkins M. D., Storey D. G.(2015). Phenotypic and genotypic comparison of epidemic and non-epidemic strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from individuals with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One 10e0143466 10.1371/journal.pone.0143466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson J., Rosenfeld M., McNamara S., Ramsey B., Gibson R. L.(2002). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 3491–100. 10.1002/ppul.10127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S. A., Turner S. M., Bosch B. J., Hardy C. C., Woodhead M. A.(1996). Lung function in bronchiectasis: the influence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur Respir J 91601–1604. 10.1183/09031936.96.09081601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foweraker J. E., Laughton C. R., Brown D. F., Bilton D.(2005). Phenotypic variability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputa from patients with acute infective exacerbation of cystic fibrosis and its impact on the validity of antimicrobial susceptibility testing. J Antimicrob Chemother 55921–927. 10.1093/jac/dki146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambello M. J., Iglewski B. H.(1991). Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR gene, a transcriptional activator of elastase expression. J Bacteriol 1733000–3009. 10.1128/jb.173.9.3000-3009.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellatly S. L., Needham B., Madera L., Trent M. S., Hancock R. E.(2012). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PhoP–PhoQ two-component regulatory system is induced upon interaction with epithelial cells and controls cytotoxicity and inflammation. Infect Immun 803122–3131. 10.1128/IAI.00382-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham M. I., Sundaram S., Laughton C. R., Haworth C. S., Bilton D., Foweraker J. E.(2009). Variable antibiotic susceptibility in populations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting patients with bronchiectasis. J Antimicrob Chemother 63728–732. 10.1093/jac/dkp007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girod S., Zahm J. M., Plotkowski C., Beck G., Puchelle E.(1992). Role of the physiochemical properties of mucus in the protection of the respiratory epithelium. Eur Respir J 5477–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeminne P. C., Scheers H., Decraene A., Seys S., Dupont L. J.(2012). Risk factors for morbidity and death in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of CT diagnosed bronchiectatic patients. Respir Res 1321. 10.1186/1465-9921-13-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A. K., Lodha R., Kabra S. K.(2015). Non cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Indian J Pediatr 82938–944. 10.1007/s12098-015-1866-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C., Alnassafi K., Hu H., Elkins M., Bye P., Rose B., Cordwell S., Triccas J. A., Harbour C., et al. (2013). Modulation of gene expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa during chronic infection in the adult cystic fibrosis lung. Microbiology 1592354–2363. 10.1099/mic.0.066985-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurlier K., Dénervaud V., Haenni M., Guy L., Krishnapillai V., Haas D.(2005). Quorum-sensing-negative (lasR) mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa avoid cell lysis and death. J Bacteriol 1874875–4883. 10.1128/JB.187.14.4875-4883.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho P. L., Chan K. N., Ip M. S., Lam W. K., Ho C. S., Yuen K. Y., Tsang K. W.(1998). The effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection on clinical parameters in steady-state bronchiectasis. Chest 1141594–1598. 10.1378/chest.114.6.1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L. R., Kulasekara H. D., Emerson J., Houston L. S., Burns J. L., Ramsey B. W., Miller S. I.(2009). Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants are associated with cystic fibrosis lung disease progression. J Cyst Fibros 866–70. 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogardt M., Heesemann J.(2013). Microevolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to a chronic pathogen of the cystic fibrosis lung. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 35891–118. 10.1007/82_2011_199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Nguyen D. T., Son M. S., Hoang T. T.(2008). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PsrA responds to long-chain fatty acid signals to regulate the fadBA5 β-oxidation operon. Microbiology 1541584–1598. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018135-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem E., Corey M., Gold R., Levison H.(1990). Pulmonary function and clinical course in patients with cystic fibrosis after pulmonary colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Pediatr 116714–719. 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)82653-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King P. T., Holdsworth S. R., Freezer N. J., Villanueva E., Holmes P. W.(2006). Characterisation of the onset and presenting clinical features of adult bronchiectasis. Respir Med 1002183–2189. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King P. T., Holdsworth S. R., Freezer N. J., Villanueva E., Holmes P. W.(2007). Microbiologic follow-up study in adult bronchiectasis. Respir Med 1011633–1638. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler T., Curty L. K., Barja F., van Delden C., Pechere J.-C.(2000). Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J Bacteriol 1825990–5996. 10.1128/JB.182.21.5990-5996.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosorok M. R., Zeng L., West S. E., Rock M. J., Splaingard M. L., Laxova A., Green C. G., Collins J., Farrell P. M.(2001). Acceleration of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis after Pseudomonas aeruginosa acquisition. Pediatr Pulmonol 32277–287. 10.1002/ppul.2009.abs [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang Z., Hao Y., Walling B. E., Jeffries J. L., Ohman D. E., Lau G. W.(2011). Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase provides an escape from phagocytosis by degrading the pulmonary surfactant protein-A. PLoS One 6e27091. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFayette S. L., Houle D., Beaudoin T., Wojewodka G., Radzioch D., Hoffman L. R., Burns J. L., Dandekar A. A., Smalley N. E., et al. (2015). Cystic fibrosis-adapted Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing lasR mutants cause hyperinflammatory responses. Sci Adv 1e1500199. 10.1126/sciadv.1500199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Kosorok M. R., Farrell P. M., Laxova A., West S. E., Green C. G., Collins J., Rock M. J., Splaingard M. L.(2005). Longitudinal development of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and lung disease progression in children with cystic fibrosis. JAMA 293581–588. 10.1001/jama.293.5.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonon M. K., Woods D. E., Straus D. C.(1988). Production of lipase by clinical isolates Pseudomonas cepacia. J Clinic Microbiol 26979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorè N. I., Cigana C., De Fino I., Riva C., Juhas M., Schwager S., Eberl L., Bragonzi A.(2012). Cystic fibrosis-niche adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa reduces virulence in multiple infection hosts. PLoS One 7e35648 10.1371/journal.pone.0035648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luján A. M., Moyano A. J., Segura I., Argaraña C. E., Smania A. M.(2007). Quorum-sensing-deficient (lasR) mutants emerge at high frequency from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutS strain. Microbiology 153225–237. 10.1099/mic.0.29021-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah T. F., Pitts B., Pellock B., Walker G. C., Stewart P. S., O'Toole G. A.(2003). A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature 426306–310. 10.1038/nature02122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens C. J., Inglis S. K., Valentine V. G., Garrison J., Conner G. E., Ballard S. T.(2011). Mucous solids and liquid secretion by airways: studies with normal pig, cystic fibrosis human, and non-cystic fibrosis human bronchi. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301L236–L246. 10.1152/ajplung.00388.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathee K., Narasimhan G., Valdes C., Qiu X., Matewish J. M., Koehrsen M., Rokas A., Yandava C. N., Engels R., et al. (2008). Dynamics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1053100–3105. 10.1073/pnas.0711982105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane P. J., Naureckas E. T., Strek M. E.(2012). Bronchiectasis in a diverse US population: effects of ethnicity on etiology and sputum culture. Chest 142159–167. 10.1378/chest.11-1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhanna M. J., Ferkol T., Martin R. J., Dreshaj I. A., van Heeckeren A. M., Kelley T. J., Haxhiu M. A.(2001). Nitric oxide deficiency contributes to impairment of airway relaxation in cystic fibrosis mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 24621–626. 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.5.4313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray T. S., Kazmierczak B. I.(2006). FlhF is required for swimming and swarming in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 1886995–7004. 10.1128/JB.00790-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K., Obata K., Keira T., Miyata R., Hirakawa S., Takano K., Kohno T., Sawada N., Himi T., et al. (2014). Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase causes transient disruption of tight junctions and downregulation of PAR-2 in human nasal epithelial cells. Respir Res 1521. 10.1186/1465-9921-15-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell A. E., Barker A. F., Ilowite J. S., Fick R. B.(1998). Treatment of idiopathic bronchiectasis with aerosolized recombinant human DNase I. Chest 1131329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole G. A., Kolter R.(1998). Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol 30295–304. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A., Cantón R., Campo P., Baquero F., Blázquez J.(2000). High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 2881251–1254. 10.1126/science.288.5469.1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkins M. D., Glezerson B. A., Sibley C. D., Sibley K. A., Duong J., Purighalla S., Mody C. H., Workentine M. L., Storey D. G., et al. (2014). Twenty-five-year outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting individuals with cystic fibrosis: identification of the prairie epidemic strain. J Clin Microbiol 521127–1135. 10.1128/JCM.03218-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasteur M. C., Helliwell S. M., Houghton S. J., Webb S. C., Foweraker J. E., Coulden R. A., Flower C. D., Bilton D., Keogan M. T.(2000). An investigation into causative factors in patients with bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1621277–1284. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9906120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penesyan A., Kumar S. S., Kamath K., Shathili A. M., Venkatakrishnan V., Krisp C., Packer N. H., Molloy M. P., Paulsen I. T.(2015). Genetically and phenotypically distinct Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates share a core proteomic signature. PLoS One 10e0138527. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez L. R., Machado A. B., Barth A. L.(2013). The presence of quorum-sensing genes in Pseudomonas isolates infecting cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis patients. Curr Microbiol 66418–420. 10.1007/s00284-012-0290-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchelle E., Bajolet O., Abély M.(2002). Airway mucus in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev 3115–119. 10.1016/S1526-0550(02)00005-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujana I., Gallego L., Martín G., López F., Canduela J., Cisterna R.(1999). Epidemiological analysis of sequential Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from chronic bronchiectasis patients without cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 372071–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimmann C., Beyeler M., Latifi A., Winteler H., Foglino M., Lazdunski A., Haas D.(1997). The global activator GacA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO positively controls the production of the autoinducer N-butyryl-homoserine lactone and the formation of the virulence factors pyocyanin, cyanide, and lipase. Mol Microbiol 24309–319. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3291701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust L., Messing C. R., Iglewski B. H.(1994). Elastase assays. Methods Enzymol 235554–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust L., Pesci E. C., Iglewski B. H.(1996). Analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase (lasB) regulatory region. J Bacteriol 1781134–1140. 10.1128/jb.178.4.1134-1140.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha A. J.(2004). Java Treeview – extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics 203246–3248. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoz K. M., Mitzimberg S. M., Schuster M.(2007). Social cheating in Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 10415876–15881. 10.1073/pnas.0705653104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz A. E., Olivier K. N., Steiner C. A., Montes de Oca R., Holland S. M., Prevots D. R.(2010). Trends and burden of bronchiectasis-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1993-2006. Chest 138944–949. 10.1378/chest.10-0099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz A. E., Olivier K. N., Adjemian J., Holland S. M., Prevots R.(2012). Trends in bronchiectasis among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2000 to 2007. Chest 142432–439. 10.1378/chest.11-2209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K., Sayeed S., Antalis P., Gladitz J., Ahmed A., Dice B., Janto B., Dopico R., Keefe R., et al. (2006). Extensive genomic plasticity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa revealed by identification and distribution studies of novel genes among clinical isolates. Infect Immun 745272–5283. 10.1128/IAI.00546-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P. K., Schaefer A. L., Parsek M. R., Moninger T. O., Welsh M. J., Greenberg E. P.(2000). Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407762–764. 10.1038/35037627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. E., Buckley D. G., Wu Z., Saenphimmachak C., Hoffman L. R., D'Argenio D. A., Miller S. I., Ramsey B. W., Speert D. P., et al. (2006). Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1038487–8492. 10.1073/pnas.0602138103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol P. A., Ohman D. E., Iglewski B. H.(1979). A more sensitive plate assay for detection of protease production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol 9538–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa A. M., Pereira M. O.(2014). Pseudomonas aeruginosa diversification during infection development in cystic fibrosis lungs – a review. Pathogens 3680–703. 10.3390/pathogens3030680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingpej P., Smith L., Rose B., Zhu H., Conibear T., Al Nassafi K., Manos J., Elkins M., Bye P., et al. (2007). Phenotypic characterization of clonal and nonclonal Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from lungs of adults with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 451697–1704. 10.1128/JCM.02364-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga J. J., Barbier M., Mulet X., Bielecki P., Bartell J. A., Owings J. P., Martinez-Ramos I., Hittle L. E., Davis M. R., et al. (2015). Genotypic and phenotypic analyses of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic bronchiectasis isolate reveal differences from cystic fibrosis and laboratory strains. BMC Genomics 16883. 10.1186/s12864-015-2069-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weycker D., Edelsberg J., Oster G., Tino G.(2005). Prevalence and economic burden of bronchiectasis. Clin Pulm Med 12205–209. 10.1097/01.cpm.0000171422.98696.ed [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Workentine M. L., Sibley C. D., Glezerson B., Purighalla S., Norgaard-Gron J. C., Parkins M. D., Rabin H. R., Surette M. G.(2013). Phenotypic heterogeneity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations in a cystic fibrosis patient. PLoS One 8e60225. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]