Abstract

Streptococcus pyogenes group A Streptococcus (GAS) is the most common cause of bacterial throat infections, and can cause mild to severe skin and soft tissue infections, including impetigo, erysipelas, necrotizing fasciitis, as well as systemic and fatal infections including septicaemia and meningitis. Estimated annual incidence for invasive group A streptococcal infection (iGAS) in industrialised countries is approximately three per 100,000 per year. Typing is currently used in England and Wales to monitor bacterial strains of S. pyogenes causing invasive infections and those isolated from patients and healthcare/care workers in cluster and outbreak situations. Sequence analysis of the emm gene is the currently accepted gold standard methodology for GAS typing. A comprehensive database of emm types observed from superficial and invasive GAS strains from England and Wales informs outbreak control teams during investigations. Each year the Bacterial Reference Department, Public Health England (PHE) receives approximately 3,000 GAS isolates from England and Wales. In April 2014 the Bacterial Reference Department, PHE began genomic sequencing of referred S. pyogenes isolates and those pertaining to selected elderly/nursing care or maternity clusters from 2010 to inform future reference services and outbreak analysis (n = 3, 047). In line with the modernizing strategy of PHE, we developed a novel bioinformatics pipeline that can predict emmtypes using whole genome sequence (WGS) data. The efficiency of this method was measured by comparing the emmtype assigned by this method against the result from the current gold standard methodology; concordance to emmsubtype level was observed in 93.8% (2,852/3,040) of our cases, whereas in 2.4% (n = 72) of our cases concordance was observed to emm type level. The remaining 3.8% (n = 117) of our cases corresponded to novel types/subtypes, contamination, laboratory sample transcription errors or problems arising from high sequence similarity of the allele sequence or low mapping coverage. De novo assembly analysis was performed in the two latter groups (n = 72 + 117) and was able to diagnose the problem and where possible resolve the discordance (60/72 and 20/117, respectively). Overall, we have demonstrated that our WGS emm-typing pipeline is a reliable and robust system that can be implemented to determine emm type for the routine service.

Keywords: Streptococcus pyogenes, Group A streptococci, Emm typing, Whole genome sequencing, Microbial genomics

Introduction

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) or Streptococcus pyogenes is a human pathogen causing infections ranging from mild bacterial throat infection to severe septicaemia and meningitis (Cunningham, 2000). Invasive GAS infections (iGAS), though relatively uncommon compared to highly prevalent non-invasive GAS infections, are a significant global cause of morbidity and mortality. An increase in the incidence rates of iGAS in the last two decades (Cunningham, 2000; Meehan et al., 2013; Guy et al., 2014) has led to the introduction of national enhanced surveillance protocols in a number of developed countries, including the UK (Lamagni & Williams, 2009). In England and Wales, multiple outbreaks of S. pyogenes infection occur each year in locations such as schools, care homes, hospitals and family clusters. Sequence analysis of the emm gene is the main method used to aid bacterial discrimination and inform epidemiological study of group A streptococcal clusters and monitor the prevalence of types nationally within the population.

The emm gene encodes for the M-protein, a surface protein and a major virulence factor in GAS (Sanderson-Smith et al., 2014). The N-terminus hypervariable region of the M-protein is the source of its antigenic diversity and the targeted region for emm gene sequence typing (Beall, Facklam & Thompson, 1996; Facklam et al., 1999). Currently there are more than 200 emm types described (McMillan et al., 2013), but only a small proportion of these have been validated for the expression of the M-antigen (Denny & Perry, 1957; Lancefield, 1959).

The recent advances in whole genome sequencing technologies resulted in reduced costs and reduced turnaround times making this technology accessible to reference microbiology. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is not just an alternative to Sanger sequencing but can offer increased resolution and higher predictive value for emm typing as demonstrated by Athey et al. (2014). Here we describe the implementation and validation of a novel WGS-based emm typing tool within a reference microbiology lab for a large dataset of GAS isolates (n = 3, 047).

Materials and Methods

Isolates

Reference strains (n = 10) for all serotypes were acquired from PHE archives whereas 3047 clinical isolates were collected and sequenced prospectively over a period of 14 months, between April 2014 and May 2015. The FASTQ files for the isolates described in Athey et al. (2014) (n = 191) were obtained from the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) study PRJNA233611.

Microbiology

Streptococcus pyogenes isolates were cultured using standard methods (Johnson et al., 1996). The Public Health England National Streptococcal Reference Laboratory (Bacteriology Reference Department) performed emm gene sequence typing on referred isolates obtained as previously described (Podbielski, Melzer & Lütticken, 1991; Beall, Facklam & Thompson, 1996) using a crude DNA extract for PCR and Sanger sequencing. In brief, the emm types were determined according to the protocol and guidelines available on the CDC website (https://www.cdc.gov/streplab/protocol-emm-type.html). When sequence data obtained using the CDC recommended primers generate ambiguous sequence, alternative primers (MF1, 59-ATAAGGAGCATAAAAATGGCT-39, and MR1, 59-AGCTTAGTTTTCTTCTTTGCG-39) (Podbielski, Melzer & Lütticken, 1991) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used for the amplification of the emm gene (Podbielski, Melzer & Lütticken, 1991). For whole genome sequencing preparation, purified DNA was prepared by using the QIAsymphony SP automated instrument (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and QIAsymphony DSP DNA Mini Kit, using the manufacturer’s recommended tissue extraction protocol for Gram positive bacteria (including a 1 h pre-incubation with mutanolysin and lysozyme followed by 2 h incubation with proteinase K in ATL buffer and RNAse A treatment). DNA concentrations were measured using the Quant-iT dsDNA Broad-Range Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and GloMaxR 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega, Southampton, UK). A Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used followed by sequencing using a HiSeq 2500 System (Illumina) and the 2 × 100-bp paired-end mode.

Bioinformatic processing

Casava 1.8.2 (Illumina inc. San Diego, CA, USA) was used to deplex the samples and FASTQ reads were processed with Trimmomatic (Bolger, Lohse & Usadel, 2014) to remove bases from the trailing end that fall below a PHRED score of 30. Processed FASTQ reads from all sequences in this study were submitted to ENA using the ena_submission tool (https://github.com/phe-bioinformatics/ena_submission) and can be found at the PHE Pathogens BioProject PRJEB17673 at ENA (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/PRJEB17673; Table S1).

K-mer identification software (https://github.com/phe-bioinformatics/kmerid) was used to compare the sequence reads with a panel of curated NCBI RefSeq genomes to identify the species. A sample of k-mers (DNA sequences of length k) in the sequence data are compared against the k-mers of 1,769 reference genomes representing 59 pathogenic genera obtained from RefSeq (NCBI Reference Sequence Database). The reference genome containing the most k-mers found in the sample is identified, and provides initial confirmation of the species. This step also identifies samples containing more than one species of bacteria (i.e., mixed cultures) and any bacteria misidentified as S. pyogenes by the sending laboratory. Further analysis continued only if S. pyogenes was identified.

Emm gene typing tool implementation

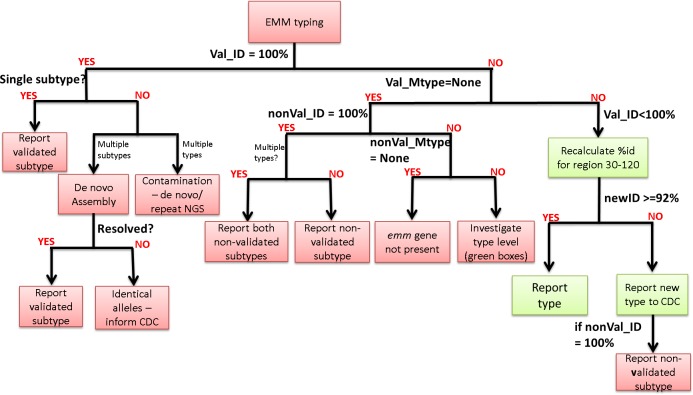

The emm gene typing tool assigns emm type and subtype by querying the CDC M-type specific database (ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/infectious_diseases/biotech/tsemm/). An updated version of the database is downloaded on a weekly base and genomic reads are mapped to the latest version using bowtie2 (version 2.1.0; following options used: –fr –no-unal –minins 300 –maxins 1100 -k 99999 -D 20 -R 3 -N 0 -L 20 -I S,1,0.50) (Langmead & Salzberg, 2012). At this stage the validated emm genes (emm1–124; validated refers to confirmation of M protein presence using antiphagocytic tests (Horstmann et al., 1988; Beall, Facklam & Thompson, 1996; Facklam et al., 1999; Facklam et al., 2002)) were separated from the non-validated (emm125+, STC and STG) and both sets were analysed in parallel. In each set, alleles with 100% coverage (minimum depth of 5 reads per bp) over the length of their sequences and >90% identity were selected and the allele with the highest percentage identity was reported. Following this selection, a decision algorithm (Fig. 1) is implemented to determine (a) whether the validated or not validated emm type will be reported, (b) whether emm type or subtype will be reported and (c) whether further investigation is necessary (i.e., contamination, new type or presence of two emm subtypes). Due to the stringent filters implemented by this tool, in some cases, low coverage at the 5′ end of the allele, resulted to the non-validated emm type being reported when in fact the validated emm type was present. To avoid this, such cases are marked with ‘**’ and reported as ‘Not determine’ so that further investigation is instigated. The emm-typing tool is publicly available in GitHub (https://github.com/phe-bioinformatics/emm-typing-tool).

Figure 1. Decision algorithm for the assignment of emm type/subtype.

The decision algorithm is based on the CDC guidelines that clinical scientists currently follow for assigning emm type available at http://www.cdc.gov/streplab/assigning.html.

Decision algorithm

The decision algorithm for the assignment of emm type/subtype follows the CDC guidelines (http://www.cdc.gov/streplab/assigning.html). An emm subtype is assigned only in cases of 100% identity over the entire 180 bp length of the allele sequence. The allele sequence corresponds to the first 150 bp of the emm gene plus 30 bp from the upstream sequence corresponding to the signal peptide portion. If subtype cannot be assigned, the emm type can be assigned if >92% identity is observed over the length of bases 30–120 which correspond to the first 90 bp of the emm gene.

The first part of the decision algorithm works within the emm typing tool; it attempts to assign emm subtype/type using the validated result first and if a validated emm type cannot be assigned or no validated result is available then emm subtype or type is assigned based on the non-validated result. In cases where an emm type or subtype cannot be assigned, the decision workflow (Fig. 1) can help to determine the appropriate course of action based on the reported results for the validated and non-validated set; for example, if two emm types are reported in the validated set this indicates contamination and the sample should be re-extracted and re-sequenced, whereas if two emm subtypes are reported then the genomic data should be assembled and further analysis performed to resolve and assign the correct emm subtype.

De novo assembly

Genomic reads were assembled using SPAdes (version 2.5.1) de novo assembly software (Bankevich et al., 2012) with the following parameters ‘spades.py –careful -1 strain.1.fastq.gz -2 strain.2.fastq -t 4 -k 33,55,77,85,93′. The resulting contigs.fasta file was converted into a BLAST database using blast+ (version 2.2.27) (Camacho et al., 2009) and queried using selected query sequence (i.e., allele sequence).

Results

Comparing Sanger sequencing and WGS-based emm typing results

Group A Streptococcus isolates (n = 3, 047) collected over a period of 14 months, between April 2014 and May 2015, were sequenced and emm gene typing data derived from genomic analysis were compared to data derived using the traditional Sanger sequencing method. Six isolates were removed from the analysis due to low yield following whole genome sequencing. Of the remaining 3,041 isolates, 2852 (93.8%; 95% CI [92.9–94.6]%) were concordant to emm subtype level (matched over the full length of the allele; 180 bps), whereas 72 (2.4%; CI [1.8–2.9]%) were concordant to emm type level (matched over the region 30-120) and only 117 (3.8%; CI [3.2–4.6]%) were discordant (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of emm typing results by Sanger and WGS-based sequencing.

Results shown for the 20 most common emm types (corresponding to >85% of the study dataset). Concordant to emm subtype, emm type level, and discordant are represented as “TRUE”, ‘TRUE?” and “FALSE”, respectively.

| M-type (Wet lab) | NGS analysis | Grand Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample failure | TRUE | TRUE? | FALSE | ||

| 1.0 | 557 | 17 | 574 | ||

| 3.1 | 1 | 413 | 6 | 21 | 441 |

| 12.0 | 302 | 9 | 7 | 318 | |

| 89.0 | 296 | 2 | 9 | 307 | |

| 28.0 | 206 | 1 | 10 | 217 | |

| 75.0 | 1 | 124 | 1 | 5 | 131 |

| 4.0 | 2 | 112 | 2 | 116 | |

| 3.93 | 79 | 2 | 4 | 85 | |

| 6.0 | 77 | 1 | 2 | 80 | |

| 87.0 | 58 | 3 | 61 | ||

| 94.0 | 49 | 1 | 50 | ||

| 11.0 | 44 | 1 | 45 | ||

| 2.0 | 38 | 1 | 1 | 40 | |

| 44.0 | 31 | 2 | 33 | ||

| 18.0 | 1 | 27 | 1 | 29 | |

| 5.23 | 28 | 1 | 29 | ||

| 81.0 | 24 | 2 | 26 | ||

| 6.4 | 20 | 1 | 21 | ||

| 73.0 | 19 | 19 | |||

| 22.0 | 18 | 18 | |||

| Other | 1 | 361 | 17 | 28 | 407 |

| Grand Total | 6 | 2,852 | 72 | 117 | 3,047 |

Of the 72 isolates concordant to emm type level, seven were assigned different subtypes using the two methods, one was assigned two non-validated emm types (emm159.0/emm246.0), one of which (emm 246.0) corresponded to the PCR-derived result and three were assigned subtype by WGS but were only assigned type by Sanger sequencing. Another isolate was originally typed as a mixed culture (emm3.1/emm12.0) using the traditional method and following WGS analysis on single colonies only type emm3.1 was detected. The remaining 60 were assigned subtype by Sanger sequencing but were only assigned type by whole-genome sequencing. Upon further investigation, it became apparent that the emm gene typing tool was unable to call subtype due to the presence of mixed subtypes (n = 6) or mixed bases (n = 54); these are positions where a non-reference nucleotide is present in 20–80% of the reads making it impossible to call a consensus nucleotide. Interestingly, 31/54 isolates with mixed bases were emm44 and this constituted the total number of emm44 isolates available in this study, suggesting that there might be a correlation between this emm type and the presence of mixed subtype variants within patients; an observation that warrants further investigation. The 60 isolates with mixed signature and the six subtype discordances were analysed further using de novo assembly and BLAST analysis. This approach was able assign a single subtype for all 60 isolates with mixed signature, with the emm allele identified in the assembly matching the subtype previously detected by Sanger sequencing. In the case of the seven isolates, where different subtypes were called, this approach confirmed the original WGS result. Further investigation into the sequence trace files, revealed that in five of these isolates analysis was done on a shorter PCR amplicon, suggesting amplification bias.

Of the 117 discordant isolates, 89 were due to different emm types being called with the two methods, four were flagged as ‘Not determined’ by WGS, four were flagged as mixed emm types, four were non-typeable by Sanger but typed to emm subtype level with WGS and 16 were flagged as possible new type by WGS. All discordant isolates were analysed further using de novo assembly and BLAST analysis.

The ‘mixed’ flag is assigned when two validated emm types are present with 100% coverage and identity (n = 4) whereas ‘Not determined’ flag is assigned when two or more alleles are present with the same percent identity but <100% (n = 1). ‘Not determine’ is also assigned when the validated emm type has low coverage issues in the last 1–3 bases of the 5′ end. In this case emm type will be tagged with ‘**’ (n = 3). De novo assembly analysis was able to confirm presence of multiple emm genes in the five mixed isolates (attributed to contamination) and assign the validated emm type in the remaining three isolates (Table S2).

Further investigation of the 16 isolates flagged as carrying emm gene sequences not currently in the database (new types; all emm3 type) by WGS revealed that in all cases low mapping coverage (failed coverage = 100% filter due to base coverage <5 reads in one or more bases) towards the end of the emm gene sequence detected by Sanger sequencing was responsible for this result. De novo assembly analysis confirmed the presence of the emm allele previously detected by Sanger sequencing for these 16 isolates (12/16 emm3.1).

In the four cases where isolates were non-typeable by Sanger sequencing, this was attributed to problems with PCR amplification and/or mixed traces from Sanger sequencing data; these were assigned an emm type by WGS suggesting that this method has increased ability to differentiate between emm and emm-like genes.

De novo analysis suggested that in 76 of the 89 isolates with different emm types being called with the two methods, discordance was due to laboratory sample transcriptional error (Table S3). In the remaining 13 cases the presence of two emm genes was confirmed; in eight cases, pairs of validated emm genes were found suggesting laboratory contamination, whereas in one case, a validated (emm75) and non-validated gene (emm170) were found with Sanger method calling the non-validated type and WGS correctly calling the validated type. In another case, WGS returned the non-validated gene due to low coverage of the validated emm gene (only one read covering the last 20 bps) despite the mechanism to tag low coverage issues; in this scenario coverage and depth metrics fall below the threshold for accepting an allele even though the allele is assembled by the de novo assembly method.

In another three cases, where the Sanger method was calling the non-validated and WGS was calling the validated type, de novo analysis revealed that the two genes (emm60/emm169.3, emm34/emm 230) were actually quite similar and when analysed using BLAST methodology against the assembly were found to map to the same region; in fact when aligning against the emm type defining region (30–120 bps) more than 92% identity was observed for the validated emm types. In this situation, WGS has correctly assigned the validated emm gene.

Finally, in four cases, isolates assigned as non typeable by Sanger sequencing due to problems of PCR amplification and/or mixed traces during Sanger sequencing, were assigned an emm type by WGS suggesting that this method has increased ability to differentiate between emm and emm-like genes (Table S3).

De novo investigation of known and novel emm/emm-like pairs

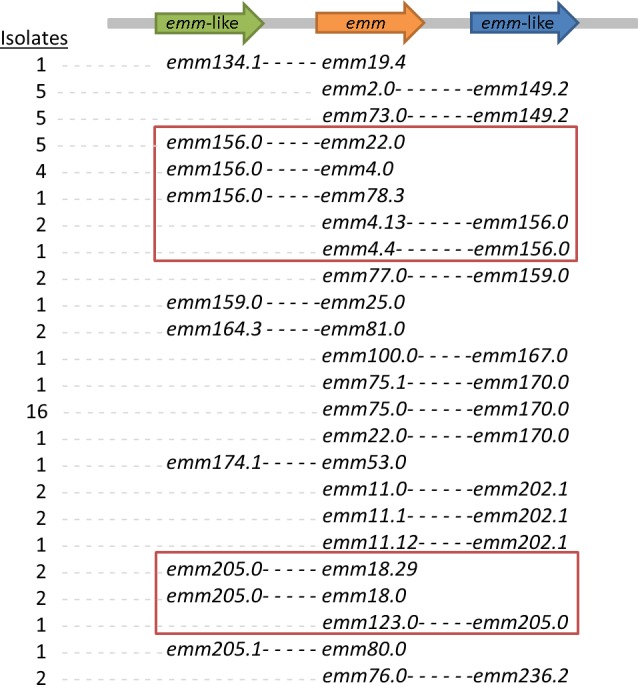

As previously described by Athey et al. (2014), the presence of emm-like genes in the CDC emm typing database, can in some cases complicate WGS-based emm typing. Our emm gene typing tool is able to resolve this by reporting the presence of validated and non-validated emm genes and using this approach it was possible to identify pairs of emm/emm-like genes by selecting those where both validated and non-validated emm-genes are present with 100% identity. Positional analysis in a subset of our isolates, using de novo assembly and BLAST confirmed the presence of both genes (Table S4). This analysis confirmed a number of previously described emm-like genes (emm170, emm159 and more) (Athey et al., 2014) and also identified novel ones (emm134 and emm167).

Further investigation into the position of the emm-like genes in relation to the emm gene revealed that emm-like genes can be found either before or after emm in gene regions previously described for mrp and enn, respectively (Athey et al., 2014) (Fig. 2). Most emm- like genes were found either exclusively before or after emm suggesting that they could belong to the mrp or enn gene family. However, two emm-like genes (emm156.0 and emm205.0) have been found in both positions depending on the accompanying emm gene.

Figure 2. Schematic showing the chromosomal arrangement of emm/emm-like gene pairs.

Positional analysis using de novo assembly and BLAST analysis was performed on representatives of isolates with 100% coverage/identity of both emm and emm-like genes.

Validation of the emm typing tool using Athey et al. isolates

The emm typing tool was further validated using the Canadian isolates used in Athey et al. (2014). Following analysis with the emm typing tool the results were compared to the results previously reported. In 186/191 cases the results obtained in this study are concordant with the results obtained in Athey et al. (Table S5). However, since in Athey et al. the results were reported to emm type not subtype, the comparison is limited to emm type. De novo assembly was used to investigate the five discordant cases, In two cases our pipeline predicted emm60 whereas the earlier study predicted emm169.3; blast analysis revealed presence of both genes with 100% identity for emm169.3 but >92% identity for the emm60 defining region (30–120 bp), therefore based on the CDC guidelines emm60 type should be assigned. In a third case, emm138.0 was assigned in this study and emm 192 was assigned previously; blast analysis revealed presence of both genes with 100% identity for emm138.0 and 99% identity for emm192. In the fourth case, the sample previously assigned emm4 was now assigned emm236.3 and blast analysis revealed presence of both genes with 100% identity. Further investigation into the mapping approach revealed low depth (<5 reads) for position 180 of emm4. Finally, the fifth case was previously assigned emm14 but our approach detected a mixed sample (emm14.3/emm51.0); blast analysis confirmed presence of both genes with 100% identity (Table S5).

Discussion

The recent reduction in price and turnaround time for WGS, and the rapid development of bioinformatics infrastructures to analyse and store the large amount of data generated are making this technology accessible to reference microbiology (Loman et al., 2012). However, before this technology can be implemented, steps need to be taken to ensure backward compatibility with the current ‘gold standard’ typing methodologies and schemes. Unlike serology-based typing methods, where a change to WGS would entail a complete change in methodology (Kapatai et al., 2016), sequencing-based methods like MLST and emm typing only require a change of sequencing platform. Already, Athey et al. (2014) have shown that WGS can be used to derive emm type from genomic data with the right bioinformatics tools.

In this study we present a novel bioinformatics tool for WGS-based emm gene typing, that uses a mapping approach, incorporating the CDC emm typing database (source file updated weekly) as a reference, and a decision algorithm resembling the decision process currently used by clinical scientists in the lab. Our emm typing tool, uses the logic within the decision algorithm (Fig. 1) to differentiate between validated (emm genes) and non-validated (emm or emm-like genes) emm types and assign emm type with a precision that allows emm subtype reporting.

A cohort of 3047 GAS isolates, previously emm typed by Sanger sequencing, were submitted to genomic sequencing and analysed using the emm typing tool. Results were collected from 3,041 isolates (six failed genomic sequencing) and following initial comparisons, concordance was observed for 2,852 isolates (93.8%) to emm subtype level, whereas for 72 (2.4%) isolates concordance was observed to emm type level. Following further investigation this emm-type/subtype discrepancy was attributed to the sensitivity of the mapping approach: for 60/72 cases the emm subtype was not called due to the presence of mixed bases in certain positions (n = 54) or mapping to more than one subtypes (tag: ‘mixed subtypes’; n = 6) that prevented the assignment of a consensus base, and de novo assembly and BLAST analysis were able to correctly assign the emm subtype in relation to Sanger sequencing results. The presence of mixed bases could be due to the presence of multiple subtypes and may be lineage specific as the majority of isolates 31/54 in this study corresponded to emm44. In 7/72 cases, emm subtype discrepancies were due to different subtypes called with the two methods and de novo analysis was unable to resolve this as it confirmed the mapping-based WGS result. However, further investigation into the Sanger sequence files revealed an amplicon problem stemming from PCR amplification bias in 5/7 of these cases, indicating the original Sanger result is most likely to have been incorrect. One of the remaining 5/72 isolates was a confirmed mixed sample (emm3.1/emm 12.0) by Sanger sequencing where multiple (n = 3) single colonies were used for WGS. Unfortunately in this case all colonies were emm3.1 but this is due to the colonies picked and not a failure of the method; for a second mixed isolate (emm3.1/emm12.0) analysed using the same approach, WGS analysis reported two colonies emm3.1 and 1 colony emm12.0.

The remaining 117 discrepant isolates were discordant at different levels: 76 isolates had different emm types due to possible errors in laboratory labelling and de novo assembly confirmed the mapping result. In 13 cases de novo assembly identified presence of a mixed emm profile that is the presence of two validated emm types in the same genomic sequence. Mapping identified the emm type with the highest coverage and missed the second type due to incomplete locus coverage; four cases were non-typeable by Sanger sequencing due to the presence and preferential sequencing of non-specific PCR amplicons but emm subtype was reported by WGS; 16 cases were flagged as ‘New type’ by WGS but further analysis identified this as a result of low mapping coverage; four cases were flagged as ‘Mixed sample’ where two emm types are reported with 100% identity whereas four other cases were flagged as ‘Not determined’, as result of two or more validated emm alleles reported with the same percent identity (100% > id > 90% plus 100% coverage) (n = 1) or low mapping coverage at the 5′ end (n = 3). De novo analysis was able to confirm presence of multiple emm genes in the five mixed isolates and assigned the tagged (‘**’) emm type to the remaining three.

Furthermore, in order to compare this method with the previously described method (Athey et al., 2014), the isolates from Athey et al. where analysed using our emm-typing tool and in 186/191 cases where concordant (to emm type level since no subtype was provided in previous reference). The five discordant cases were investigated further using de novo assembly and two cases where due to the previously described emm60/emm169.3 issue, whereas one case Athey et al. reported the non-validated typed (emm192) whereas our tool detected presence of both alleles (emm138.0/emm192.0) but reported the validated type (emm138.0). In the remaining two cases, one was tagged as having low coverage issues and de novo assembly assigned the previously reported type whereas the other was reported by mapping as mixed which was then confirmed by de novo. The two methods, although both using a mapping approach, differ in the scoring method for assigning top hit; whereas our approach uses coverage and identity to identify validate non-validated types, the approach described by Athey et al. uses the SRST2 scoring system that uses binomial testing (Inouye et al., 2014).

Overall, our analysis demonstrates that WGS can be used for emm typing; in 93.8% of the cases (2852 concordant + 1 single colony match to one of mixed emm types) the emm typing tool was able to assign the correct emm subtype unaided whereas in 2.6% of the cases (60 called to type, 3 ‘Not determined’ and 16 ‘New type’) de novo assembly was used to help assign the correct emm subtype. Using both methods, 96.4% concordance to the traditional Sanger sequencing results was observed. These cases highlighted some problems stemming from the sensitivity of mapping; mixed bases when the presence of an alternative bases in 20–80% of the reads hinders a consensus call for those positions and mixed subtypes when the two allele sequences share high similarity. The latter usually involves alleles where the downstream flanking sequence of the first allele is identical to part of the sequence of the second allele; therefore reads covering both of the alleles are present. In this case using de novo assembly can clearly shows the overlap between the two sequences and usually a gap in the one of the alleles. As demonstrated here, these issues can be resolved if de novo assembly is used and no repeat is necessary. In contrast problems with Sanger sequencing (PCR amplicon or sequence trace problems) usually require a repeat of the entire process (n = 15). In one case, allele emm170.0 was amplified and reported by Sanger sequencing when both mapping and de novo assembly demonstrated presence of both emm75.0 and emm170.0. These two alleles are frequently seen together in isolates from the UK and emm170.0 is a known emm-like gene (Athey et al., 2014); issues with these two alleles are common in our laboratory and usually seen as mixed chromatographs, which then necessitates the use of alternative primers to resolve. Our WGS approach has been specifically designed to report presence of validated and non-validated emm types and thus can detect presence of such emm/emm-like pairs.

In this study, we have demonstrated that our emm-typing tool can confidently call emm subtype from WGS data and, in the rare cases were mapping cannot assign emm subtype, de novo assembly can be used to determine the emm subtype. Although de novo assembly is a useful tool, it does have certain limitations that restrict its usage in a reference laboratory setting. One of the main issues is the lack of local quality metrics that can inform on the area of interest. Even though there are metrics to inform on the quality of the assembly, there is no detailed information for the specific area analysed whereas mapping can offer quality metrics (identity, coverage, depth, mixed bps) for the exact region that is used for each analysis. Furthermore, de novo assembly is time-consuming and considering that in the majority of the cases, the mapping approach was able to successfully assign the correct emm subtype it would have been superfluous to implement for all isolates.

In cases where emm/emm-like gene pairs were detected, de novo analysis was used to further investigate and confirm their presence. Most emm-like genes are localised exclusively before or after the emm gene suggesting that based on the <mrp-emm-enn> structure they could be assigned to mrp or enn respectively. However, emm 205.0 and emm156.0 seem to alternate positions based on their respective emm pair suggesting that the previously suggested structure <mrp-emm-enn> is not stable and can vary in some strains.

The automated nature of the emm typing tool enables incorporation into routine pipelines and results can be populated into laboratory information systems using custom scripts, thus avoiding potential errors associated with manual result recording and data entry, enhancing reference microbiology.

Supplemental Information

The ‘Not determined’ flag is assigned when the emm gene typing tool is unable to resolve the allele with the highest percentage identity due to the presence of two or more alleles with the same percent identity. Isolates flagged as ‘Not determined’ were assembled using SPAdes and BLAST analysis was used to investigate the presence of all relevant alleles.

Discordant isolates were investigated further using de novo assembly and BLAST to resolve the discrepancies between the two methods.

Positional analysis using de novo assembly and BLAST analysis was used to confirm (a) the presence of both validated and non-validated emm gene types on the chromosome and (b) the status of these non-validated emm types as emm-like genes.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Roger Daniel, Chenchal Dhami, Marisa Laranjeira, Timothy Chambers and Sarah Phillips for their technical assistance in performing bacterial purification, DNA extraction, emm typing of Streptococcus pyogenes strains included in this study. Whole genome sequencing was performed by Catherine Arnold and the team in Genome Services and Development Unit, PHE Colindale. Thanks also go to the CDC streptococcus lab, USA for provision and maintenance the emm allele database and all health care scientists and microbiologists for the submission of strains to the reference laboratory.

Funding Statement

The authors received no funding for this work.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Georgia Kapatai conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables.

Juliana Coelho conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Steven Platt conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Victoria J. Chalker conceived and designed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Code repository for emm-typing-tool: https://github.com/phe-bioinformatics/emm-typing-tool.

Raw data for the 3047 GAS isolates can be found at the PHE Pathogens BioProject PRJEB17673 at ENA.

References

- Athey et al. (2014).Athey TBT, Teatero S, Li A, Marchand-Austin A, Beall BW, Fittipaldia N. Deriving group A streptococcus typing information from short-read whole-genome sequencing data. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014;52:1871–1876. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00029-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich et al. (2012).Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall, Facklam & Thompson (1996).Beall B, Facklam R, Thompson T. Sequencing emm-specific PCR products for routine and accurate typing of group A streptococci. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1996;34:953–958. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.953-958.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, Lohse & Usadel (2014).Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho et al. (2009).Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham (2000).Cunningham MW. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2000;13:470–511. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.3.470-511.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny & Perry (1957).Denny Jr FW, Perry WD, Wannamaker LW. Type-specific streptococcal antibody1. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1957;36:1092–1100. doi: 10.1172/JCI103504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facklam et al. (1999).Facklam E, Beall B, Efstratiou A, Fischetti V, Johnson D, Kaplan E, Kriz P, Lovgren M, Martin D, Schwartz B, Totolian A, Bessen D, Hollingshead S, Rubin F, Scott J, Tyrrell G. emm typing and validation of provisional M types for group A streptococci. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1999;5:247–253. doi: 10.3201/eid0502.990209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facklam et al. (2002).Facklam RF, Martin DR, Lovgren M, Johnson DR, Efstratiou A, Thompson TA, Gowan S, Kriz P, Tyrrell GJ, Kaplan E, Beall B. Extension of the Lancefield classification for group A streptococci by addition of 22 new M protein gene sequence types from clinical isolates: emm103 to emm124. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;34:28–38. doi: 10.1086/324621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy et al. (2014).Guy R, Williams C, Irvine N, Reynolds A, Coelho J, Saliba V, Thomas D, Doherty L, Chalker V, Von Wissmann B, Chand M, Efstratiou A, Ramsay M, Lamagni T. Increase in scarlet fever notifications in the United Kingdom, 2013/2014. Eurosurveillance. 2014;19 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.12.20749. Article 20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstmann et al. (1988).Horstmann RD, Sievertsen HJ, Knobloch J, Fischetti VA. Antiphagocytic activity of streptococcal M protein: selective binding of complement control protein factor H. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:1657–1661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye et al. (2014).Inouye M, Dashnow H, Raven L-A, Schultz MB, Pope BJ, Tomita T, Zobel J, Holt KE. SRST2: rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Medicine. 2014;6(90) doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson et al. (1996).Johnson DR, Kaplan EL, Sramek J, Bicova R, Havlicek J, Havlickova H, Kritz P, Motlova J. Laboratory diagnosis of group A streptococcal infections. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kapatai et al. (2016).Kapatai G, Sheppard CL, Al-Shahib A, Litt DJ, Underwood AP, Harrison TG, Fry NK. Whole genome sequencing of Streptococcus pneumoniae: development, evaluation and verification of targets for serogroup and serotype prediction using an automated pipeline. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2477. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamagni & Williams (2009).Lamagni T, Williams C. National enhanced surveillance of severe group A streptococcal disease PROTOCOL. Health Protection Agencyhttps://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/571359/National_enhanced_surveillance_of_severe_group_A_stretococcal_disease_protocol_2009.pdf 2009

- Lancefield (1959).Lancefield RC. Persistence of type-specific antibodies in man following infection with group A streptococci. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1959;110:271–292. doi: 10.1084/jem.110.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead & Salzberg (2012).Langmead B, Salzberg S. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman et al. (2012).Loman NJ, Constantinidou C, Chan JZM, Halachev M, Sergeant M, Penn CW, Robinson ER, Pallen MJ. High-throughput bacterial genome sequencing: an embarrassment of choice, a world of opportunity. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2012;10:599–606. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan et al. (2013).McMillan DJ, Drèze P-A, Vu T, Bessen DE, Guglielmini J, Steer AC, Carapetis JR, Van Melderen L, Sriprakash KS, Smeesters PR. Updated model of group A Streptococcus M proteins based on a comprehensive worldwide study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2013;19:E222–E229. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan et al. (2013).Meehan M, Murchan S, Bergin S, O’Flanagan D, Cunney R. Increased incidence of invasive group A streptococcal disease in Ireland, 2012 to 2013. Eurosurveilance. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.33.20556. Article 20556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podbielski, Melzer & Lütticken (1991).Podbielski A, Melzer B, Lütticken R. Application of the polymerase chain reaction to study the M protein(-like) gene family in beta-hemolytic streptococci. Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 1991;180:213–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00215250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson-Smith et al. (2014).Sanderson-Smith M, De Oliveira DMP, Guglielmini J, McMillan DJ, Vu T, Holien JK, Henningham A, Steer AC, Bessen DE, Dale JB, Curtis N, Beall BW, Walker MJ, Parker MW, Carapetis JR, Van Melderen L, Sriprakash KS, Smeesters PR, Batzloff M, Towers R, Goossens H, Malhotra-Kumar S, Guilherme L, Torres R, Low D, Mc Geer A, Krizova P, El Tayeb S, Kado J, Van der Linden M, Erdem G, Moses A, Nir-Paz R, Ikebe T, Watanabe H, Sow S, Tamboura B, Kittang B, Melo-Cristino J, Ramirez M, Straut M, Suvorov A, Totolian A, Engel M, Mayosi B, Whitelaw A, Darenberg J, Henriques B, Ni CC, Wu J-J, De Zoysa A, Efstratiou A, Shulman S, Tanz R, Johnson D, Srinivasan V. A systematic and functional classification of Streptococcus pyogenes that serves as a new tool for molecular typing and vaccine development. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;210:1325–1338. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The ‘Not determined’ flag is assigned when the emm gene typing tool is unable to resolve the allele with the highest percentage identity due to the presence of two or more alleles with the same percent identity. Isolates flagged as ‘Not determined’ were assembled using SPAdes and BLAST analysis was used to investigate the presence of all relevant alleles.

Discordant isolates were investigated further using de novo assembly and BLAST to resolve the discrepancies between the two methods.

Positional analysis using de novo assembly and BLAST analysis was used to confirm (a) the presence of both validated and non-validated emm gene types on the chromosome and (b) the status of these non-validated emm types as emm-like genes.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Code repository for emm-typing-tool: https://github.com/phe-bioinformatics/emm-typing-tool.

Raw data for the 3047 GAS isolates can be found at the PHE Pathogens BioProject PRJEB17673 at ENA.