Abstract

Tethered growth factors offer exciting new possibilities for guiding stem cell behavior. However, many of the current methods present substantial drawbacks which can limit their application and confound results. In this work, we developed a new method for the site-specific covalent immobilization of azide-tagged growth factors and investigated its utility in a model system for guiding neural stem cell (NSC) behavior. An engineered interferon-γ (IFN-γ) fusion protein was tagged with an N-terminal azide group, and immobilized to two different dibenzocyclooctyne-functionalized biomimetic polysaccharides (chitosan and hyaluronan). We successfully immobilized azide-tagged IFN-γ under a wide variety of reaction conditions, both in solution and to bulk hydrogels. To understand the interplay between surface chemistry and protein immobilization, we cultured primary rat NSCs on both materials and showed pronounced biological effects. Expectedly, immobilized IFN-γ increased neuronal differentiation on both materials. Expression of other lineage markers varied depending on the material, suggesting that the interplay of surface chemistry and protein immobilization plays a large role in nuanced cell behavior. We also investigated the bioactivity of immobilized IFN-γ in a 3D environment in vivo and found that it sparked the robust formation of neural tube-like structures from encapsulated NSCs. These findings support a wide range of potential uses for this approach and provide further evidence that adult NSCs are capable of self-organization when exposed to the proper microenvironment.

Keywords: Strain-promoted alkyneazide cycloaddition, Neural stem cells, Central nervous system regeneration, Protein immobilization, Neuroepithelium

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Signaling proteins are used in a wide variety of tissue engineering strategies, both in soluble and immobilized form, to guide stem cell behavior.[1] In the adult mammalian central nervous system (CNS), which does not innately regenerate following injury,[2] it is particularly important to provide the proper cues and microenvironment so that functional integration can occur. Immobilizing signaling proteins can improve the duration and level of signaling while spatially sequestering them within the material, affording greater control over local cellular behavior.[3] Within the CNS, injuries result from mechanical damage and begin a secondary injury cascade, which can last for months.[4, 5] The transplantation of neural stem cells (NSCs) has been investigated as a potential therapy for CNS regeneration, with a wide variety of outcomes.[6] However, simply transfusing NSCs by themselves is insufficient, as the cells must be provided with the right cues and microenvironment to differentiate and functionally integrate with existing tissue. Encapsulating NSCs within a biomimetic hydrogel conduit can provide protection, locate the cells within the injury site, control lineage specification, and guide neurite outgrowth.[7] To guide the differentiation of encapsulated NSCs, the material can be functionalized with lineage directing (signaling) proteins. In fact, platelet-derived growth factor-AA (PDGF-AA) can be used to specify oligodendrocytes,[3, 8] bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) to specify astrocytes,[3] and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) to specify neurons.[9] Ideally, and for enhanced precision and latency, signaling proteins would be site-specifically tagged for immobilization, rather than simply sequestered within a matrix. Proteins can be site-specifically labeled through enzymatic means[10, 11] or by the incorporation of non-canonical amino acids.[12] Unlike non-canonical amino acids, which require nonsense suppression and carefully controlled synthetic tRNAs, enzymatic labeling offers a straightforward method for controlled, site-specific protein modification. It is also important to provide a permissive microenvironment to encourage the self-organization of encapsulated NSCs, with the eventual goal of generating functionally integrated tissue.

The material and immobilization chemistry employed have large implications both for efficacy and translational considerations. The material itself should be biomimetic and neuroinductive. Recapitulating moieties and repeat units found within the CNS and carefully controlling stiffness can strongly influence the behavior of encapsulated cells.[13, 14] A wide variety of materials have been investigated for this purpose, such as hyaluronan/methyl-cellulose blends,[15] collagen,[16] fibrin,[17] and chitosan.[7] An immobilization chemistry that is stable and bio-orthogonal should be employed to afford greater control over the presentation of signaling proteins and improve the potential for clinical translation, as well as reduce the number of factors which could affect cellular behavior. Strain-promoted alkyneazide cycloaddition (SPAAC) has been used in many biological systems to tag biomolecules, including proteins and nucleic acids.[18] However, its use for the guidance of stem cell behavior has not been extensively investigated.

Our previous work has demonstrated the impressive neurogenic capabilities of immobilized IFN-γ.[7, 3, 9, 19] IFN-γ is a type-II interferon which is not natively expressed within the CNS, but nonetheless shows many potent effects.[20] In this study, our goals were to improve upon previous immobilization techniques (biotin-streptavidin conjugation), compare IFN-γ immobilization across different materials, and investigate the response of NSCs in more detail (Figure 1), both in vitro and in vivo. As pluripotent stem cells undergo programmed neural differentiation, they organize into neural rosettes under specific conditions.[21] These clusters of cells can develop into neural tubes or even form neuroepithelium in vitro.[22] However, such behavior is typically only associated with pluripotent-derived NSCs and not primary adult NSCs.[22] Unexpectedly, our previous work uncovered the ability of adult rat NSCs to self-organize and form neural tube-like structures. This is a novel finding which deserves further investigation. For the current study, we hypothesized that proteins incorporating a site-specific azide-tag can be covalently immobilized under physiologic conditions to alkyne-functionalized hydrogels using SPAAC with no loss in bioactivity.

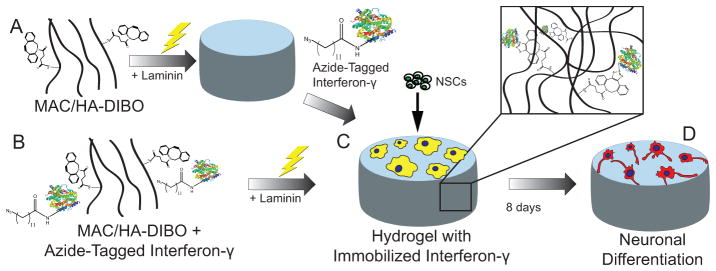

Figure 1.

Overview of azIFN-γ ‘click’ immobilization and in vitro NSC differentiation. A) azIFN-γ was immobilized to crosslinked hydrogels (in situ immobilization) or B) immobilized to polymer in solution prior to hydrogel formation (de novo immobilization). C) NSCs were seeded on top of 2D azIFN-γ-functionalized hydrogels where they D) differentiated into neurons after 8 d. Hydrogels were formed from methacrylamide chitosan (MAC) or methacrylated hyaluronan (MA-HA).

To prove this, we N-terminally labeled a recombinant IFN-γ fusion protein with an azide tag through the use of N-myristoyltransferase.[11] Next, we investigated the immobilization of this protein (azIFN-γ) to a biomimetic hydrogel, methacrylamide chitosan (MAC). We demonstrated that this approach results in the stable, bio-orthogonal, covalent tethering of azIFN-γ, and can be used for immobilization to intact hydrogels or polymer in solution. We then compared the biological response between this material and methacrylated hyaluronan (MA-HA, a polysaccharide found natively in the CNS) in vitro, to demonstrate the utility of this approach when applied to a different hydrogel material. Lastly, we were interested to determine the extent to which our previous observations of adult NSC self-organization were affected by the presence of streptavidin, and whether we could reproduce previous results with covalent immobilization. Thus, we assessed the bioactivity of covalently immobilized azIFN-γ in vivo and the ability of this approach to direct the self-organization of NSCs.

2. Materials and Methods

Synthesis of 12-azidododecanoic acid (12-ADA)

Synthesis of 12-ADA was performed as previously described by Heal et al.[11] Briefly, 2 g of 12-bromododecanoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was esterified in methanol (Sigma-Aldrich) at reflux for 3 h in the presence of concentrated sulfuric acid (EMD). The product (an oil) was then dissolved in 60 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO,VWR) and 519 mg of sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. This reaction was stirred at RT for 16 h, and then quenched with 1M hydrochloric acid (EMD). The product (an oil) was then purified via flash chromatography (9:1 cyclohexane:diethyl ether solvent system, both from Sigma-Aldrich). Finally, the eluate (an oil) was dissolved in 2M sodium hydroxide (VWR) and methanol. This was stirred at RT for 24 h, and then acidified using 2M hydrochloric acid. After concentrating, the final product (an off-white solid) was analyzed by electrospray ionization ion-trap mass spectrometry (ESI-IT-MS) and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (H1NMR). The results from these characterizations matched those previously published:[11] H1NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.26, 2.35, 1.61-1.64, 1.28. ESI-IT-MS (in methanol with sodium trifluoroacetate, both Sigma-Aldrich): Calculated m/z = 240.1712, found = 240.8

Design, Expression, and Purification of Recombinant Azide-Tagged Interferon-γ

The interferon-γ fusion protein (azIFN-γ) consisted of an N-terminal myristoylation sequence (MGLYVS),[11] a flexible hinge (EFPKPSTPPGSSGGAP), [23] the active domain of murine IFN-γ (NCBI Ref NP 620235.1, AA23-AA156), [9] a tobacco etch virus-cleavable spacer (ENLYFQG),[24] and a C-terminal 6x His tag (Figure 2).[25] The amino acid sequence was optimized for E. coli expression (Genscript) and inserted into a pET28a vector. Myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase (CaNMT) inserted into a pET11c vector was generously obtained from Dr. Edward Tate (Imperial College London). CaNMT and azIFN-γ were co-expressed within E. coli and purified as previously described.[11, 25] Briefly, BL21 (DE3) E. coli cultures were grown in 1.8 L of 47.6 mg/mL Terrific Broth (EMD) with 8 mL/L glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich), 200 μg/mL ampicillin (Chem-Impex), and 50 μg/mL kanamycin (Chem-Impex). After the cultures reached an optical density of 0.7, 500 μM 12-ADA was added (for no azide tag controls, 12-ADA was omitted) and expression of both proteins induced by 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Chem-Impex) and maintained at 37 °C for 4 h. The culture medium was centrifuged and stored at −80°C until isolation. azIFN-γ was isolated under denaturing conditions and purified via nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA, Thermo Scientific) resin affinity chromatography. After elution, the protein was refolded as described in[9] and purified further through fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC, GE AKTApurifier 10 with Frac-950 collector). The final product was assayed via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF) and the concentration measured using bicinchoninic acid (Micro BCA, Thermo Scientific). Aliquots of azIFN-γ were stored at −80 °C until use; all aliquots were subjected to a maximum of one freeze-thaw cycle.

Figure 2.

azIFN-γ design and production. A recombinant fusion protein was designed, consisting of an azide-tagging sequence, a flexible spacer to allow for proper refolding, the active domain of IFN-γ, a TEV protease cut site (to enable removal of the 6His tag), and a 6His tag for Ni-NTA purification. This protein was N-terminally tagged with 12-ADA to enable SPAAC immobilization.

Isolation and Culture of Neural Stem Cells

All procedures involving animals were approved by the University of Akron institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC). NSCs were derived from the subventricular zone of adult (6–8 wk old) female Wistar rats (Envigo) as previously described.[26] NSCs were expanded as neurospheres using growth medium: neurobasal medium, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/mL penicillin-streptomycin, B27 supplement (all Life Technologies), 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF, Sigma-Aldrich), 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, Peprotech), and 2 μg/mL heparin (Sigma-Aldrich). Low passage number (3–6) cells were used for all experiments.

Soluble azIFN-γ Bioactivity

NSCs were dissociated and plated onto coverslips. The coverslips were prepared by first treating with 50 μg/mL poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) and then coating with 5 μg/mL laminin (Life Technologies). NSCs were allowed to adhere for 24 h in growth medium before being changed to basal medium (growth medium without EGF, bFGF, or heparin) supplemented with 150 ng/mL of azIFN-γ, azIFN-γ without an azide-tag, or commercially available IFN-γ (Peprotech). After 8 d total, NSCs were fixed using methanol and stained using anti-βIII-tubulin (Covance, 1:500 dilution) with goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa-Fluor 546 (Life Technologies, 1:400 dilution) secondary antibody. The extent of neuronal differentiation was determined by counting the number of βIII-tubulin-positive cells and dividing by the total number of nuclei (stained by Hoechst 33342, Thermo Scientific). Imaging was performed on an Olympus IX81 with MetaMorph Advanced software (Molecular Devices).

Synthesis of MAC-DIBO and HA-DIBO

MAC was synthesized as previously described,[27] using Protosan UP B 80/20 chitosan (NovaMatrix) and methacrylic anhydride (Sigma-Aldrich). Following lyophilization, MAC was dissolved at 2 wt% in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich), pH 7.4. 7.86 × 10−3 mg/mL dibenzocyclooctyne-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (DIBO-NHS, Click Chemistry Tools) was added and the solution vortexed. This reaction was shaken at RT for 3 h before dialysis in deionized (DI) water (12–14 kDa dialysis tubing, Spectrum Labs) with 9 buffer changes. The final product was lyophilized before use. MA-HA was also synthesized as previously described,[28] using sodium hyaluronate (Fisher Scientific) and methacrylic anhydride. The pH was adjusted to 8–9 using 5 N sodium hydroxide, and the reaction proceeded at 4°C for 24 h. Excess methacrylic acid and methacrylic anhydride were removed via dialysis in DI water. Following lyophilization, MA-HA was dissolved at 1 wt% in PBS. 5 mM sulfo-NHS (Chem-Impex) and 0.1 M 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC, Chem-Impex) were added.[29] After vortexing, 5.4×10−3 mg/mL of DIBO-amine (Click Chemistry Tools) was added and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 h before dialysis. The final product was lyophilized before use. Functionalization was confirmed by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR): 2 wt% MAC, MAC-DIBO, MA-HA, or HA-DIBO solutions were coated onto calcium fluoride windows, allowed to dry overnight in a desiccator, and analyzed using transmission FTIR (Nicolet is50R, Thermo Scientific). Spectrographic analysis was conducted using Spekwin32 software (F. Menges, Version 1.72.2).

Rheological Analysis of HA-based Gels

While we have studied the rheological properties of MAC-based gels before,[26] we wanted to examine the gelation properties and moduli of HA-based gels and match them to MAC prior to use in cell studies. Gels were formed under a variety of conditions (varying amounts of crosslinker and UV exposure time) in a 4 mm deep mold (cut from silicone rubber, McMaster-Carr). Following crosslinking, they were washed in PBS for 24 h. The rheological properties of the gels were measured on an Ares RFS-III rheometer (Rheometric Scientific) with 8 mm parallel plates. A dynamic frequency sweep (strain controlled, 1% strain) was conducted from 1 to 100 Hz. We measured the elastic modulus (G’), the viscous modulus (G”), the dissipation factor (tanδ), and calculated the complex modulus (G′). The complex modulus is reported here (Figure S2), as it provides a good comparison with past results without requiring geometric assumptions (such as Poisson’s ratio).

azIFN-γImmobilization

For all experiments involving hydrogels, 2 wt% gels were prepared in the following manner: first, a 2.268 wt% solution of polysaccharide (either MA-HA, HA-DIBO, MAC, or MAC-DIBO) was dissolved in ultrapure (Type 1) water. Following dissolution, 10X PBS was added to adjust the final concentration to 2 wt% in PBS, pH 7.4. This solution was then autoclaved prior to gelation. To form hydrogels, a photoinitiator (1-Hydroxycyclohexyl phenyl ketone, Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved at 300 mg/mL into 1-Vinyl-2-pyrrolidinone (Sigma-Aldrich) and sterile filtered (0.2 μm, Pall Corporation) before use. For HA-based gels, 2.5 μL initiator solution was added per gram of polysaccharide solution, while MAC-based gels required 3 μL/g. These solutions were then mixed in a dual asymmetric centrifugal mixer (3 min, 3000 rpm: SpeedMixer DAC 150 FVZ, Hauschild Engineering) prior to crosslinking via UV exposure (365 nm, 2.7 mw/cm2) for 2.5 minutes (HA-based gels) or 3 minutes (MAC-based gels).

For analysis of de novo immobilization efficiency, sterile-filtered azIFN-γ was added to MAC-DIBO (or IFN-γ to MAC for adsorbed controls) prior to crosslinking at 150 ng per g of solution. This solution was gently mixed at 4°C for 1 h before crosslinking. Gels were formed (100 μL) in 96-well plates (Greiner) and transferred to 1.7 mL centrifuge tubes (VWR). Gently, 500 μL sterile PBS was added to each tube, and the tubes were gently mixed at 37°C for 24 h. The PBS was then removed, and fresh PBS was added. This process was repeated a total of 3 times. Following the 3rd wash, the gels were suspended in 500 μL lysozyme solution (50 mg/mL in PBS, pH 5.0, Sigma-Aldrich) and gently disrupted by pipetting repeatedly through a wide-bore, 1000 μL micropipette tip. The gels were digested in lysozyme solution at 37 °C for 72 h. After this time, insoluble material was removed via centrifugation (10,000 x g for 2 min) and the concentration of azIFN-γ or IFN-γ remaining in the soluble phase determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, Peprotech). The amount of protein remaining in the gels following washing was then calculated and expressed as a percent of total protein added.

Analysis of de novo immobilization efficiency in MA-HA gels proceeded similar to that of MAC gels. After immobilization and washing, the MA-HA gels were digested in hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich, 0.5 mg/mL) overnight at 37 °C.

For analysis of in situ immobilization, gels were prepared as before (100 μL in 96-well plates), but without any azIFN-γ or IFN-γ added prior to crosslinking. Instead, gels were placed into solutions containing 150 ng/mL of either azIFN-γ (MAC-DIBO) or IFN-γ (MAC) and increasing amounts of BSA (0, 10, 20, or 30 wt%) or FBS (0, 10, 30, 45, 60 mg/mL). BSA solutions were prepared by measuring the appropriate mass of BSA before dissolving in PBS, while FBS was prepared by dilutions from an FBS stock solution (qualified FBS, Gibco), with the starting concentration determined by Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). All solutions were sterile filtered prior to being added to the gels. It is worth noting that qualified FBS is inconsistent in composition,[30] and does contain active proteins: we found that placing our gels in qualified FBS at high concentrations (>30 mg/mL) resulted in rapid (<4 h) dissolution. This problem was mitigated by heat-inactivating the FBS prior to use (56 °C for 30 min, RT for 30 min), thus heat-inactivated FBS was used for all immobilization experiments. The gels were incubated in the protein solutions for 3 h at 37°C, then washed 3 times in PBS. Following washing, the gels were digested in lysozyme and the amount of azIFN-γ or IFN-γ remaining was measured via ELISA as described above.

Analysis of Immobilized azIFN-γ Distribution

To visualize the distribution of azIFN-γ within the gels following in situ immobilization, the FBS-based experiment was performed as described above, but following PBS washing, the gels were embedded in a 50:50 (v:v) mixture of optimum cutting temperature (OCT, Tissue-Tek) compound and ultrapure water (gently mixed overnight, and then frozen at −20°C) and sectioned into 30 μm thick sections, both radially and axially. The sections were stained for IFN-γ (anti-IFN-γ, Peprotech) and imaged using a confocal microscope (Fluoview FV1000, Olympus, with XY-mosaic stitching to obtain images of the entire gels).

Bioactivity of Immobilized azIFN-γ

NSCs were isolated from Wistar rats as described above, and passage 3–6 cells were used in all immobilized bioactivity experiments. Gels (HA and MAC-based) with 3 levels of IFN-γ (immobilized, adsorbed, and negative control, all de novo immobilization) were formed as described above, with the following changes: photo-reactive laminin (prepared as described previously)[3] at 50 μg per g of solution was added to the polysaccharide solutions prior to asymmetric mixing to accommodate cell attachment. Additionally, the gels were crosslinked on methacrylated glass coverslips (12 mm circle, VWR, prepared as described previously)[31] and placed in 24-well plates (Greiner). After gelation, the gels were washed 2x with sterile PBS and incubated with growth medium overnight. The next day, the medium was changed again and NSCs were added at a density of 40,000 cells/cm2. The NSCs were allowed to proliferate in growth medium overnight, and the next day the medium was changed to basal medium. The cells differentiated in basal medium for 7 d (8 d total). On day 8, the samples were either digested for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR, 4 samples per treatment) or fixed for immunocytochemistry (ICC, 4 samples per treatment, per stain).

qPCR Analysis of NSC Differentiation

Following the completion of differentiation, the samples (glass coverslips with hydrogels and NSCs) were moved to a new 24-well plate. RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lysis was performed in each well, and consisted of physical disruption with a pipette tip and mixing via pipetting. Genomic DNA was removed via gDNA Eliminator spin column as instructed. The final RNA concentration and quality was measured spectrophotometrically (Infinite M200 with NanoQuant plate, Tecan). All samples had purity (ratio of absorbance at 260 to 280 nm) values greater than 2.0. Following RNA extraction, samples were adjusted to the same RNA concentration (i.e., all samples were diluted to match the lowest value) and cDNA was synthesized immediately using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Negative controls consisted of both no template and no reverse transcriptase. qPCR analysis was performed using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche) on a Roche LightCycler 480 II. The forward and reverse primers used have been previously published;[13] concentrations of F and R primers ranged from 0.300 to 0.500 μM and were optimized prior to performing qPCR. qPCR was achieved by the following steps: 15 min activation (95 °C), 15 s at 94°C, 15 s at 60°C, and 10 s at 72°C. Forty-five total cycles were performed. A standard curve was performed on-plate for each gene and the on-plate efficiency was used in successive calculations. Efficiencies ranged from 91% to 104%. Crossing point (CP) and efficiency values were determined using LightCycler 480 Software (Roche) via the 2nd derivative max method. Relative fold change was determined using the method described in ref,[32] with all values normalized to MAC control (no IFN-γ). No amplification of either control (no template and no reverse-transcriptase) was observed.

Immunocytochemical Analysis of NSC Differentiation

On day 8, samples (NSCs and gels on glass coverslips) were fixed via methanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and stained for: βIII-tubulin (neurons), GFAP (astrocytes, Cell Signaling, 1:400 dilution), RIP (oligodendrocytes, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:5 dilution), or nestin (progenitors, BD Biosciences, 1:20 dilution) with goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa-Fluor 546 (Life Technologies, 1:400 dilution) secondary antibody for all primary antibodies. All nuclei were stained using Hoechst 33342 to enable positive cell quantification (marker-expressing cells/total cells). Samples were mounted (ProLong Gold, Thermo) and imaged using an Olympus IX81 with MetaMorph Advanced software.

Subcutaneous Maturation

All surgical procedures involving animals were approved by the University of Akron institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) and performed asceptically, under anesthesia. For in vivo bioactivity studies, Fisher 344 rats were used both for the subcutaneous implantation and NSC isolation (Envigo). First, NSCs were isolated from Fisher 344 rats as described above and expanded in culture as neurospheres (using growth medium). Scaffolds were formed as previously described,[3] with the following changes: first, instead of MAC, MAC-DIBO was used to form the hydrogel. azIFN-γ was reacted with MAC-DIBO at 300 ng/mL overnight at 4°C. NSCs were then mixed with the MAC-DIBO hydrogel along with photoinitiator and photo-reactive laminin via dual asymmetric centrifugal mixing (1 min, 1500 RPM, Speed-Mixer DAC 150 FVZ, Hauschild Engineering). After asceptic preparation of the surgical site (shaving and washing with isopropyl alcohol and betadine), 3 in-cisions were created on each rat along the midline. The scaffolds were inserted into the subcutaneous space in the anteroposterior direction and the incisions were closed with Michel clips (9 scaffolds total, or 3 rats). Animals were allowed to recover for 4 wks under standard housing conditions. They were then euthanized via carbon dioxide, and the scaffolds were retrieved for analysis.

Immunohistological Analysis of Subcutaneously Matured Scaffolds

Scaffolds were prepared for analysis of protein expression as described previously,[3] with the following antibodies used in IHC analysis: nestin (see above), Pax-6 (Abcam, 1:100 dilution), βIII-tubulin (see above), Ki-67 (Abcam, 1:500 dilution), and Sox1 (Abcam, 1:500 dilution). Briefly, after scaffold retrieval, samples were fixed (paraformaldehyde), dehydrated, embedded in wax, sectioned, and then deparaffinized. IHC staining consisted of permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100, blocking with 10% goat serum for 2h, incubation overnight at 4°C with primary antibody, incubation for 1h at RT with secondary antibody, and then staining with Hoechst 33342 (10 μM for 7 min). All images were obtained using an Olympus IX81 microscope with MetaMorph software.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 17 software using ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis or Student’s t-test where applicable. An α level of 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. In the figures where ANOVA was conducted, groups sharing the same letter are not significantly different from each other.

3. Results

The presence of an N-terminal azide-tag on IFN-γ does not adversely affect soluble bioactivity

First, we produced an azide-tagged recombinant fusion protein (Figure 2). This protein contained an N-terminal azide-tagging sequence (based on the work of Heal et al.[11]), a flexible linker to allow for proper refolding, and the active domain of murine IFN-γ. The incorporation of an N-terminal azide tag was accomplished by co-expression of this fusion protein alongside the enzyme CaNMT and supplementation of the feeding stock with 12-ADA. MS and H1NMR confirmed successful synthesis of 12-ADA, while MALDI-ToF indicated the successful incorporation of 12-ADA into the protein sequence when comparing tagged (azIFN-γ) to untagged (IFN-γ) proteins (observed shift of +252 Da, which corresponds well to that published by other groups[33], Table S1). To verify that neither the fusion protein design nor the incorporation of the azide tag negatively affected bioactivity, we cultured NSCs on laminin-coated glass coverslips in the presence of soluble IFN-γ, azIFN-γ, a commercially available positive control, or no IFN-γ (negative control). After 8 d, ICC staining indicated that the number of βIII-tubulin (a neuronal marker, which increases in expression as NSCs differentiate into neurons) positive cells was the same across the IFN-γ groups, and much higher than the negative control (83 ± 14%, 83 ± 13%, 80 ± 15%, or 16 ± 5% for untagged, azide-tagged, commercial control, or negative control, respectively, mean ± SD, data not shown).

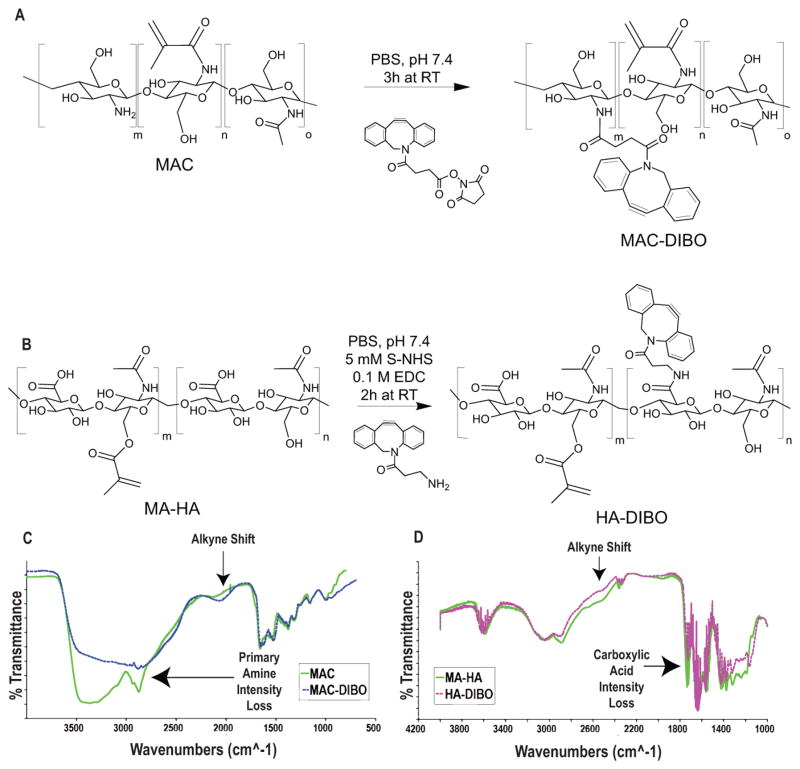

Synthesis and characterization of DIBO-functionalized polysaccharides

To enable the covalent immobilization of azIFN-γ, we chose to functionalize MAC with dibenzocyclooctyne (DIBO) (Figure 3A), avoiding the use of toxic Cu catalysts associated with terminal alkyne-azide reactions. After reacting with DIBO-N-hydroxysuccinimide in aqueous buffer, functionalization of MAC (MAC-DIBO) was verified through FTIR (Figure 3C). A loss of intensity in the amine peak and appearance of an alkyne shift indicated that MAC was successfully functionalized through reaction of its primary amines. Additionally, for biological assays, methacrylated hyaluronan-DIBO (HA-DIBO) was synthesized (Figure 3B). Since MA-HA does not have the reactive amines of MAC, DIBO-functionalization was accomplished by reaction of DIBO-amine with the carboxyl groups on MA-HA and confirmed via FTIR (Figure 3B+D). A decrease in carboxyl peak intensity was coupled with a concomitant appearance of an alkyne shift.

Figure 3.

Synthesis and characterization of MAC-DIBO and HA-DIBO. A) MAC-DIBO was synthesized by reaction of MAC with DIBO-NHS under physiologic conditions. B) HA-DIBO was synthesized by reaction of MA-HA with DIBO-Amine in the presence of S-NHS and EDC as catalysts. C+D) Confirmation of both reactions was verified by FTIR. MAC-DIBO shows a loss of amine intensity and the appearance of an alkyne shift when compared to MAC, while HA-DIBO shows a loss of carboxylic acid intensity and the appearance of an alkyne shift when compared to MA-HA. This indicates the successful functionalization of both MAC and MA-HA with DIBO to enable SPAAC immobilization of azide-tagged IFN-γ.

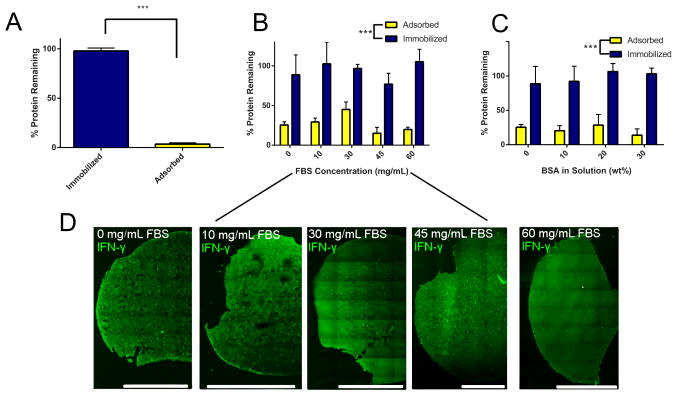

The immobilization of azIFN-γ is specific and stable

After recombinantly producing azIFN-γ, verifying its bioactivity in soluble form, and synthesizing DIBO-functionalized materials, we characterized a variety of immobilization reactions to establish the specificity and stability of our technique. First, we immobilized azIFN-γ to MAC-DIBO in solution prior to photocrosslinking (de novo immobilization, Figure 1B). Following repeated washing, substantially more protein remained when compared to adsorbed controls (≈97% vs 4%, Figure 4A). This indicates that the immobilization chemistry is efficient and stable under physiologic conditions. Next, we were interested to determine if the immobilization reaction was also specific and bio-orthogonal. SPAAC takes place between two reactive moieties that are not found within living systems: a primary azide and a cyclic alkyne.[35] An interesting application of SPAAC growth factor immobilization is to flow-through solutions of tagged protein and immobilize signaling molecules to intact hydrogels in living systems. To test this, we performed two different in situ immobilization (Figure 1A) experiments — one in the presence of high concentrations of inactive protein (bovine serum albumin, BSA) and one in the presence of physiologic concentrations of an active protein mixture (fetal bovine serum, FBS). For these two experiments, we formed MAC-DIBO hydrogels prior to reaction with azIFN-γ in solution. After forming gels, we then placed them into solutions of azIFN-γ with either BSA or FBS for 4 h. Following repeated washing, there was a significant difference in the amount of protein remaining between immobilized groups and adsorbed controls (Figure 4B+C). Furthermore, the concentration of FBS or BSA did not have a significant effect on the immobilization efficiency, demonstrating the specificity and bio-orthogonality of the reaction. The response is similar between FBS (Figure 4B) and BSA (Figure 4C), suggesting that immobilizing azIFN-γ to intact hydrogels is feasible both within high concentration (BSA) and active protein (FBS) systems. To explore this idea further, we wanted to see if the immobilized azIFN-γ was penetrating through to the entire hydrogel or undergoing primarily surface immobilization. After immobilizing azIFN-γ for 4 h in FBS, we sectioned the hydrogels and stained for IFN-γ. The sections show a uniform dispersal of azIFN-γ throughout the hydrogel, even in the presence of increasing FBS concentration, indicating that azIFN-γ immobilization occurs consistently through the whole gel (Figure 4D). Taken together, these data broaden the potential utility of in situ immobilization, as it could be used to administer different tagged growth factors over time to a specific biological location (i.e., within a hydrogel).

Figure 4.

Immobilization of azIFN-γ through various avenues to chitosan-based (MAC and MAC-DIBO) hydrogels. A) de novo immobilization results in significantly more (≈97%) protein remaining following washing when compared to adsorption (≈3%). The bars show the amount of protein remaining within the gels following washing and enzymatic digestion. B) Differing concentrations of an active protein mixture (FBS) do not affect azIFN-γ immobilization efficiency, while adsorption remains significantly lower. The range from 0 – 60 mg/mL was chosen based on the reported range of physiologic serum protein concentrations,[34] demonstrating the feasibility of our approach within living systems. C) Differing levels of inactive (BSA) protein at supraphysiological levels do not affect azIFN-γ immobilization efficiency, demonstrating the feasibility of our approach within protein-buffered systems. D) Fluorescent images of gels obtained after staining for IFN-γ show an even distribution throughout the gel. The protein was immobilized in situ in the presence of FBS at the concentrations shown in (B). No fluorescence was observed from either primary antibody (no anti-IFN-γ) or protein (no azIFN-γ) negative controls. Scale bars represent 2000 μm. Mean ± SD with n = 4. *** denotes significance (p < 0.001) as determined by two-factor ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc.

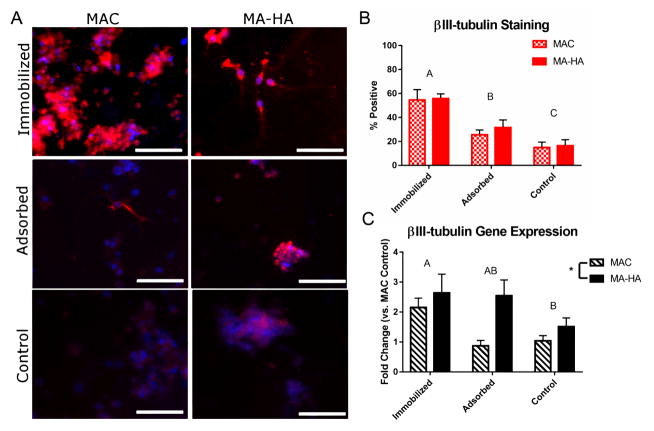

NSC response to immobilized azIFN-γ in vitro is affected by surface chemistry

Having demonstrated that soluble azIFN-γ is bioactive and the immobilization chemistry is specific and stable, we then investigated the bioactivity (as measured by its ability to differentiate NSCs) of immobilized azIFN-γ. As mentioned previously, this was investigated on two different materials. Both MAC and MA-HA were examined in three different capacities: negative control (MAC or MA-HA with no protein), adsorbed (MAC or MA-HA with untagged IFN-γ), and immobilized (MAC-DIBO or HA-DIBO with azIFN-γ). We sought to establish whether the two materials showed differences in bioactivity, whether there was a difference between immobilization and adsorption, and whether there was any sort of interaction between protein and material (possibly due to differences in electrostatic charge). Functionalized gels were formed through the de novo synthesis route and NSCs were cultured on top of the gels in a 2D environment. Prior to seeding cells, we measured the rheological properties (namely complex modulus, G*, Figure S2) of MA-HA gels and adjusted the crosslinking process accordingly to generate gels with the same substrate stiffness (≈0.2 kPa), which has been shown to influence NSC differentiation.[13] Figure 5 shows that azIFN-γ significantly increases neuronal differentiation at both the protein (ICC, Figure 5B) and gene expression (quantitative polymerase chain reaction, qPCR, Figure 5C) levels. As expected, the ICC results show the most βIII-tubulin expression in the immobilized groups, decreasing expression in the adsorbed groups, and the least expression in the negative controls. Interestingly, no significant difference was found between MAC and MA-HA at the protein expression level (p > 0.05); similar values can indeed be seen between MAC and MA-HA for all three treatments. Strong neurite formation and neuronal morphology can be seen in the immobilized groups (Figure 5A), while the adsorbed and control groups show βIII-tubulin staining in the cytoplasm of cells with more immature morphologies, further confirming the potent neurogenic effects of IFN-γ immobilization. βIII-tubulin gene expression tells a slightly different story, with the same overall trend aside from an increase in expression in the adsorbed MA-HA group. This was somewhat expected, as IFN-γ experiences stronger adsorption to MA-HA than to MAC (see above), while the amount of immobilized protein remaining was similar between MAC-DIBO and HA-DIBO (97 ± 3% and 93 ± 7%, respectively, Figures 4A and S2).

Figure 5.

Neuronal differentiation is caused by immobilized azIFN-γ. A) ICC staining of βIII-tubulin (a key neuronal marker) shows increased expression in immobilized groups for both MAC and MA-HA. Strong neuronal morphologies with longer neurite outgrowth can be seen in the immobilized groups, while the cells in the adsorbed and negative control groups show a more progenitor-like morphology. In general, βIII-tubulin is observed throughout the entire cell body. Red = βIII-tubulin, Blue = Hoechst 33342. Scale bars = 100 m. B) Quantification of ICC results shows a clear trend towards increased βIII-tubulin for immobilized groups over adsorbed and control. The material made no significant difference. Mean ± SD with n = 4. Letters denote significance as determined by two-factor ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc. n = 4. C) qPCR analysis shows a similar trend, but with increased expression in the MA-HA adsorbed group. This is likely due to the electrostatic adsorption interaction between MA-HA and IFN-γ, which increased the amount of IFN-γ available to NSCs, but not significantly enough to affect protein expression. Mean ± SE with n = 4, as determined using the method described by Hellemans et al.[32] Letters denote significance as determined by two-factor ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc; * denotes significance (p < 0.05) as determined by the same technique.

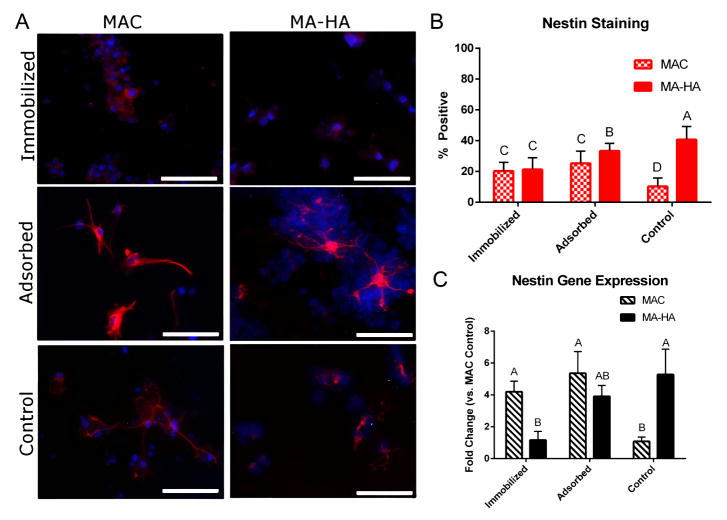

Undifferentiated NSCs are typically identified by their expression of the intermediate filament protein nestin, which is thought to be down-regulated as they differentiate.[36] We expected nestin expression (protein and gene) to decrease concomitantly with the observed increase in βIII-tubulin expression. This bears out in the MA-HA groups, with nestin expression decreasing in a manner opposite the βIII-tubulin increase (Figure 6B,C). However, this trend is not observed in the MAC groups, with both immobilized and adsorbed treatments showing higher expression than the negative control. In general, nestin positive cells showed progenitor-like morphologies within the MA-HA groups, but show characteristic neuronal morphologies within the MAC groups (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Immobilized azIFN-γ to MA-HA results in decreased nestin expression, while immobilizing it to MAC results in an increase in expression. A) Staining for nestin reveals cells with neuronal morphologies in the MAC groups while nestin-positive cells in the MA-HA groups appear as immature progenitors. Red = nestin, Blue = Hoechst 33342. Scale bars = 100 m. B) Quantification of ICC imaging shows an unexpected increase in nestin expression when compared with a negative control for MAC groups, while a decrease is seen in MA-HA groups. The increase in nestin expression for MAC groups mirrors the increase in βIII-tubulin staining seen in Figure 5. Mean ± SD with n = 4. Letters denote significance of the interaction term as determined by two-factor ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc (p < 0.05). n = 4. C) The same trend is seen in the genetic expression of nestin, with slightly different groupings. These results indicate the possible generation of NeNs from NSCs through the use of MAC. Mean ± SD with n = 4, as determined using the method described by Hellemans et al.[32] Letters denote significance of the interaction term as determined by two-factor ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc (p < 0.05).

Analysis of oligodendrocyte markers (2,3’-Cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase: RIP and CNPase, Figure S3) also reveals differences between MAC and MA-HA. Expectedly, cells expressing RIP show an immature oligodendrocytic phenotype across all groups (Figure S3A), with short, ramified branches.[37] However, the number of RIP-positive cells between MAC and MA-HA, as well as the trend (from negative control to immobilized), is dissimilar. Notably, immobilizing azIFN-γ to MAC increased RIP (Figure S3B) and CNPase (Figure S3C) expression when compared to the negative control. In MA-HA groups, immobilizing azIFN-γ had no statistically significant effect on oligodendrocyte marker expression. Immobilized and adsorbed MAC groups had the same RIP and CN-Pase expression, while RIP expression was different between immobilized and adsorbed MA-HA groups. Overall RIP expression was low, which is expected: the vast majority of NSCs in the immobilized groups differentiated into neurons (Figure 5B).

Likewise, cells expressing GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein, an intermediate filament protein expressed by astrocytes) show morphologies typical of astrocytes, with ramified branching and leaflets (Figure S4).[38] Quantification of GFAP-positive cells showed no statistically significant differences and low overall GFAP expression (Figure S4B), which is consistent with similar experiments using NSCs derived from the same niche.[26] Analysis of GFAP gene expression via qPCR (Figure S4C) indicated a significant difference between MAC and MA-HA, but no differences due to azIFN-γ immobilization.

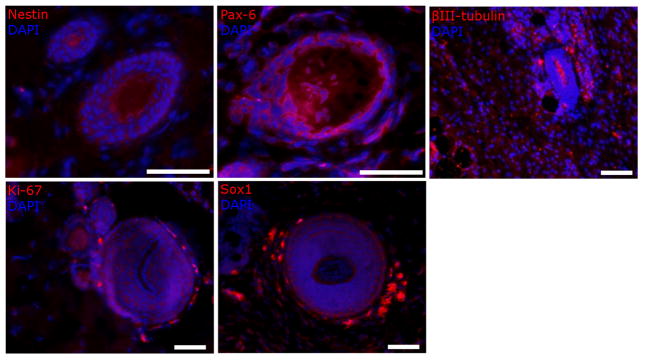

Immobilized azIFN-γ + MAC drives the self-organization of adult NSCs in vivo

Lastly, we tested the response of covalently immobilized azIFN-γ in vivo. Rather than looking purely for the molecular signatures of NSC differentiation, we were interested to see if we could observe self-organization and neurulation in a manner similar to our preliminary work.[3] After forming 3D MAC-DIBO hydrogel constructs and implanting them into rat subcutaneous tissue for 4 wks, we observed robust expression of neuroepithelium markers (Figure 7). This demonstrates that streptavidin (used in our previous study) is not responsible for guiding NSC adhesion and organization. Rather, this response is due to a combination of signaling events from the local microenvironment and cues from the immobilized azIFN-γ (we did not observe similar self-organization in adsorbed and negative controls; see reference [3]). Importantly, the structures are larger than the pore size of MAC-DIBO, indicating that signaling cues likely play a more important role than physical guidance in their formation. We observed these neural tube-like structures throughout all of the samples, and noted their presence in sequential sections, providing evidence that this is a 3D, not 2D, phenomenon. It is also worth noting that the pattern of expression for each marker is varied. For example, the βIII-tubulin-expressing cells appear to lie in the center (or apical side) of the structures while the Ki-67 and Sox1-expressing cells are located at the periphery (or basal side).

Figure 7.

Robust neural tube-like structures and self-organization from adult NSCs and immobilized azIFN-γ. After maturing 3D MAC-DIBO hydrogel constructs with encapsulated NSCs in rat subcutaneous tissue for 4 weeks, all of the samples containing immobilized azIFN-γ showed self-organized structures throughout sequential sections. The structures are much larger than the pore size of MAC (pores can be easily observed in the βIII-tubulin image). In addition to the expression of neuroepithelium markers, the NSCs can be observed to adopt a polarized orientation in some samples. Scale bars = 100 m.

4. Discussion

The above results confirmed our overall hypothesis, demonstrating the successful incorporation of an N-terminal azide tag with preserved bioactivity. The soluble differentiation results (comparing untagged, azide-tagged, and commercial control) confirmed that N-terminally tagging azIFN-γ did not significantly impact protein bioactivity. Additionally, the number of βIII-tubulin+ cells was similar to that observed in previous experiments,[19] providing further confirmation of bioactivity preservation. As azides are not normally present in biological systems,[39] this enables bio-orthogonal reactions with functionalized materials, allowing us to controllably immobilize azIFN-γ to direct NSC behavior. Prior to the current study, we (and others) have shown the utility of tethering biotinylated growth factors to streptavidin-functionalized materials.[3, 8] This presents a number of drawbacks, such as the potential immunogenicity and steric hindrance of streptavidin (a 53 kDa protein derived from Streptomyces avidinii), the presence of motifs which activate RGD integrin binding, and the lack of bio-orthogonality (biotin, or vitamin B7, is common in mammals).[40] SPAAC can circumvent all of these challenges, and has been used in a wide variety of biological applications. SPAAC is highly attractive as an alternative to biotin-streptavidin conjugation, as it can proceed in aqueous buffers at physiologic temperatures, is highly specific, and requires no toxic catalysts.[39]

We also showed that azIFN-γ can be stably immobilized to MAC-DIBO under a wide variety of conditions. One of the primary motivations for using immobilized signaling proteins (rather than soluble) is that the duration can be maintained for much longer. The persistence of immobilized azIFN-γ when compared to adsorbed IFN-γ establishes that this approach results in temporal (i.e., the immobilized molecules are permanently linked to the material) and spatial (i.e., the signaling is localized to the gel) control over growth factor presentation. The ability to immobilize azide-tagged proteins to intact hydrogels in the presence of competing proteins is useful for the potential application of different signaling proteins to a biomaterial in vivo for CNS repair. As we learn more about the timescale of signaling events that are necessary to guide the organization and integration of biomaterials-based CNS repair, our system provides the ability to use various azide-tagged growth factors to provide different cues at different times, all localized within the biomaterial. Utilizing azide-tagged, rather than soluble, factors could result in the administration of less total compound, subsequently reducing unwanted side-effects and spatially sequestering signals to the hydrogel.

The in vitro bioactivity results highlighted the importance of the interplay between surface chemistry and protein immobilization, showing some key differences between MAC and MA-HA. MAC is biomimetic (it is similar in structure to hyaluronan, the native polysaccharide within the central nervous system[41]), soluble in aqueous buffers (to enable hydrogel formation), can be quickly crosslinked, has a tunable modulus of elasticity (EY) within the range of native spinal cord tissue (0.7–0.9 kPa[26]), and has a primary amine which allows for facile functionalization. In previous experiments, we have characterized the neurogenic ability of IFN-γ immobilized to MAC hydrogels.[7, 3, 9] However, in order to more completely validate the utility of the current approach, we wanted to compare the response of NSCs exposed to azIFN-γ-functionalized MAC-DIBO with HA-DIBO. Despite being similar in structure (as mentioned above), chitosan and hyaluronan have opposite net charges,[42] providing an interesting comparison between adsorption in both systems. Since our IFN-γ fusion protein is positively charged at physiologic pH (pI = 9.21), it should experience stronger adsorption to HA-DIBO (anionic) than it does to MAC-DIBO (cationic), despite thorough washing. Indeed, this was confirmed quantitatively (11 ± 5% for MA-HA vs. 4 ± 1% for MAC, Figure S1) and through differences in bioactivity. Therefore, the use of HA-DIBO in biological assays provides an additional comparison to protein adsorption and demonstrates the applicability of our immobilization chemistry to multiple materials.

It is possible that a synergistic property of MAC and immobilized IFN-γ induces NSCs to differentiate into nestin-expressing neurons (NeNs), a subtype of neuron present within the adult rat and human brains.[43] NeNs are found in regions typically associated with higher-order cognitive function, and the expression of nestin by neurons may be associated with neuronal plasticity-related events. The potential generation of NeNs from NSCs through the use of MAC and immobilized azIFN-γ is a novel finding and warrants further investigation in future studies. The trend of increased RIP expression for IFN-γ + MAC groups agrees with previous results,[19] while the differences between control MAC and control MA-HA provide an interesting foundation for future experiments. The GFAP gene expression results show a continuation of the same trend, where MAC and MA-HA, despite being chemically similar and sharing the same stiffness, generate different NSC behavior. That this is observed only at the gene (and not protein) level demonstrates the subtlety of this effect. Since we only allowed NSCs to differentiate for 8 days, it is possible that GFAP protein expression would follow suit after a long period. Future studies will investigate more deeply the biology of azIFN-γ-orchestrated differentiation. Overall, the in vitro bioactivity results show that aspects of surface chemistry, even when controlling for stiffness and protein immobilization, drive NSC differentiation differently and display interesting interactions with immobilized azIFN-γ.

Self-organization plays a large role in normal CNS development.[44] However, as adult-derived NSCs lack the intrinsic ability to self-organize, they are unable to form the complex tissue architectures contained within the CNS and contribute to functional regeneration. The generation of cerebral organoid models in vitro from self-organizing cells is an important tool for better modeling of CNS disease and development. However, all of these techniques require the use of pluripotent stem cells.[45] Our observation that adult NSCs (which are multipotent, rather than pluripotent) self-organize in the presence of immobilized azIFN-γ represents a novel and hitherto unstudied behavior. The differences in marker localization (e.g., Ki-67-expressing cells located on the basal side) bears some similarity to the polarized expression of markers found in neural rosettes formed in vitro from pluripotent stem cells.[22] Notably, Ki-67 expression is typically localized to the basal side of the rosette (which is similar to our observations). Future studies will investigate the extent to which different protein expression is localized and how this changes with time.

The development of a method for covalently immobilizing signaling proteins allows us to study the self-organization of adult NSCs in more detail by eliminating the presence of streptavidin (which contains motifs that active RGD integrin binding [40]) as a confounding variable. Taken together with the above findings that MAC-DIBO and immobilized azIFN-γ result in the generation of NeNs, lead us to consider that MAC and MA-HA do not function identically, but rather that a synergistic response between MAC and immobilized azIFN-γ spurs NSCs into unanticipated behavior. It is reasonable to conclude that these two observations are linked; future studies will focus more into the factors that drive these phenomena.

5. Conclusions

We designed and recombinantly produced an N-terminal azide-tagged IFN-γ fusion protein (azIFN-γ) with no quantifiable loss in bioactivity. To enable SPAAC ‘click’ immobilization, we functionalized two biological polysaccharides with DIBO: MAC (MAC-DIBO, chitosan-based), and MA-HA (HA-DIBO, hyaluronan-based). We demonstrated the successful immobilization of azIFN-γ to material in solution (de novo immobilization) and fully intact hydrogels (in situ immobilization), as well as in the presence of competing protein mixtures (BSA and FBS). The distribution of azIFN-γ immobilized to intact hydrogels was homogenous. We showed that this technique can be applied to MAC and MA-HA hydrogels to guide NSC differentiation in vitro, with some interesting differences between the two materials. Namely, the combination of MAC and immobilized azIFN-γ appears to generate NENs. We also showed that immobilized azIFN-γ is bioactive in vivo and drives the self-organization of neural tube-like structures from encapsulated NSCs. Overall, this technique improves upon previous immobilization approaches (such as biotin-streptavidin conjugation) with regards to specificity and long-term translatability.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

For stem cells to be used effectively in regenerative medicine applications, they must be provided with the appropriate cues and microenvironment so that they integrate with existing tissue. This study explores a new method for guiding stem cell behavior: covalent growth factor tethering. We found that adding an N-terminal azide-tag to interferon-γ enabled stable and robust Cu-free ‘click’ immobilization under a variety of physiologic conditions. We showed that the tagged growth factors retained their bioactivity when immobilized and were able to guide neural stem cell lineage commitment in vitro. We also showed self-organization and neurulation from neural stem cells in vivo. This approach will provide another tool for the orchestration of the complex signaling events required to guide stem cell integration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge partial funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke provided by NIH grant 1R21NS096571-01 as well as partial funding from Conquer Chiari. Also the authors thank Dr. Edward Tate (Imperial College London), Mr. Erik Willet (UA) for assistance in performing and interpreting FTIR analysis, Dr. Sailaja Paruchuri (UA) for the use of her LightCycler II, and Dr. Rebecca Willits (UA) for the use of her Rheometer. Funding for the MALDI was provided in part by NIH Grant P30 CA016058 at The Ohio State University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chandra P, Lee SJ. Synthetic extracellular microenvironment for modulating stem cell behaviors. Biomark Insights. 2015;10(Suppl 1):105–16. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S20057. chandra, Prafulla Lee, Sang Jin ENG Review 2015/06/25 06:00 Biomark Insights 2015 Jun 17 10 Suppl 1 105 16 10.4137/BMI.S20057 eCol- lection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Illis LS. Central nervous system regeneration does not occur. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(4):259–63. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Koenig AM, Sloan P, Leipzig ND. In vivo assessment of guided neural stem cell differentiation in growth factor immobilized chitosan-based hydrogel scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2014;35(33):9049–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aertker BM, Bedi S, Cox JCS. Strategies for cns repair following tbi. Exp Neurol. 2016;275(Pt 3):411–26. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarhan F, Saif D, Saif A. An overview of traumatic spinal cord injury: part 1. aetiology and pathophysiology. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2012;8(6):319–325. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mothe AJ, Tator CH. Review of transplantation of neural stem/progenitor cells for spinal cord injury. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2013;31(7):701–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H, Ham TR, Neill N, Farrag M, Mohrman AE, Koenig AM, Leipzig ND. A hydrogel bridge incorporating immobilized growth factors and neural stem/progenitor cells to treat spinal cord injury. Advanced Health-care Materials. 2016;5(7):802–812. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aizawa Y, Leipzig N, Zahir T, Shoichet M. The effect of immobilized platelet derived growth factor aa on neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation on cell-adhesive hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2008;29(35):4676–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leipzig ND, Wylie RG, Kim H, Shoichet MS. Differentiation of neural stem cells in three-dimensional growth factor-immobilized chitosan hydrogel scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2011;32(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theile CS, Witte MD, Blom AEM, Kundrat L, Ploegh HL, Guimaraes CP. Site-specific n-terminal labeling of proteins using sortase-mediated reactions. Nature Protocols. 2013;8(9):1800–1807. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heal WP, Wright MH, Thinon E, Tate EW. Multifunctional protein labeling via enzymatic n-terminal tagging and elaboration by click chemistry. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(1):105–17. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JA, Lu YY, Van Deventer JA, Tirrell DA. Residue-specific incorporation of non-canonical amino acids into proteins: recent developments and applications. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14(6):774–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leipzig ND, Shoichet MS. The effect of substrate stiffness on adult neural stem cell behavior. Biomaterials. 2009;30(36):6867–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao J, Kim YM, Coe H, Zern B, Sheppard B, Wang Y. A neuroinductive biomaterial based on dopamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(45):16681–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606237103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mothe AJ, Tam RY, Zahir T, Tator CH, Shoichet MS. Repair of the injured spinal cord by transplantation of neural stem cells in a hyaluronan-based hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2013;34(15):3775–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cholas RH, Hsu HP, Spector M. The reparative response to cross-linked collagen-based scaffolds in a rat spinal cord gap model. Biomaterials. 2012;33(7):2050–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson PJ, Tatara A, McCreedy DA, Shiu A, Sakiyama-Elbert SE. Tissue-engineered fibrin scaffolds containing neural progenitors enhance functional recovery in a subacute model of sci. Soft Matter. 2010;6(20):5127–5137. doi: 10.1039/c0sm00173b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lallana E, Riguera R, Fernandez-Megia E. Reliable and effcient procedures for the conjugation of biomolecules through huisgen azide-alkyne cycloadditions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(38):8794–804. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leipzig ND, Xu C, Zahir T, Shoichet MS. Functional immobilization of interferon-gamma induces neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;93(2):625–33. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owens T, Khorooshi R, Wlodarczyk A, Asgari N. Interferons in the central nervous system: A few instruments play many tunes. Glia. 2014;62(3):339–355. doi: 10.1002/glia.22608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elkabetz Y, Panagiotakos G, Al Shamy G, Socci ND, Tabar V, Studer L. Human es cell-derived neural rosettes reveal a functionally distinct early neural stem cell stage. Genes Dev. 2008;22(2):152–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.1616208. elka-betz, Yechiel Panagiotakos, Georgia Al Shamy, George Socci, Nicholas D Tabar, Viviane Studer, Lorenz Genes Dev. 2008 Jan 15;22(2):152–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.1616208. doi:10.1101/gad.1616208. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18198334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karus M, Blaess S, Brustle O. Self-organization of neural tissue architectures from pluripotent stem cells. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522(12):2831–44. doi: 10.1002/cne.23608. karus, Michael Blaess, Sandra Brustle, Oliver J Comp Neurol. 2014 Aug 15;522(12):2831–44. doi: 10.1002/cne.23608. Epub 2014 May 7. doi:10.1002/cne.23608. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24737617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyev SM, Waibel R, Lebedenko EN, Schubiger AP, Pluckthun A. Design of multivalent complexes using the barnase*barstar module. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(12):1486–92. doi: 10.1038/nbt916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Zaro JL, Shen WC. Fusion protein linkers: property, design and functionality. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(10):1357–69. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCormick AM, Jarmusik NA, Endrizzi EJ, Leipzig ND. Expression, isolation, and purification of soluble and insoluble biotinylated proteins for nerve tissue regeneration. J Vis Exp. 2014;(83):e51295. doi: 10.3791/51295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Wijekoon A, Leipzig ND. 3d differentiation of neural stem cells in macroporous photopolymerizable hydrogel scaffolds. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu LM, Kazazian K, Shoichet MS. Peptide surface modification of methacrylamide chitosan for neural tissue engineering applications. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82(1):243–55. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smeds KA, Pfister-Serres A, Miki D, Dastgheib K, Inoue M, Hatchell DL, Grinstaff MW. Photocrosslinkable polysaccharides for in situ hydrogel formation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;54(1):115–21. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200101)54:1<115::aid-jbm14>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate Techniques. 2. Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng X, Baker H, Hancock WS, Fawaz F, McCaman M, Pungor JE. Proteomic analysis for the assessment of different lots of fetal bovine serum as a raw material for cell culture. part iv. application of proteomics to the manufacture of biological drugs. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22(5):1294–300. doi: 10.1021/bp060121o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson AE, Kobelt LJ, Leipzig ND. Immobilized ecm molecules and the effects of concentration and surface type on the control of nsc differentiation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2014;102(10):3419–3428. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hellemans J, Mortier G, De Paepe A, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. qbase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative pcr data. Genome Biol. 2007;8(2):R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulkarni C, Kinzer-Ursem TL, Tirrell DA. Selective functionalization of the protein n terminus with n-myristoyl transferase for bioconjugation in cell lysate. Chembiochem. 2013;14(15):1958–62. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall JE, Guyton AC. Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology. 12. Saunders/Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agard NJ, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. A strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition for covalent modification of biomolecules in living systems. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(46):15046–7. doi: 10.1021/ja044996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bazan E, Alonso FJ, Redondo C, Lopez-Toledano MA, Alfaro JM, Reimers D, Herranz AS, Paino CL, Serrano AB, Cobacho N, Caso E, Lobo MV. In vitro and in vivo characterization of neural stem cells. Histol Histopathol. 2004;19(4):1261–75. doi: 10.14670/HH-19.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barateiro A, Fernandes A. Temporal oligodendrocyte lineage progression: in vitro models of proliferation, differentiation and myelination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843(9):1917–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bushong EA, Martone ME, Ellisman MH. Maturation of astrocyte morphology and the establishment of astrocyte domains during postnatal hippocampal development. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22(2):73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jewett JC, Bertozzi CR. Cu-free click cycloaddition reactions in chemical biology. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39(4):1272–9. doi: 10.1039/b901970g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alon R, Bayer EA, Wilchek M. Streptavidin contains an ryd sequence which mimics the rgd receptor domain of fibronectin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1990;170(3):1236–1241. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90526-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaudet AD, Popovich PG. Extracellular matrix regulation of inflammation in the healthy and injured spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2014;258:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayitmazer AB, Koksal AF, Kilic Iyilik E. Complex coacervation of hyaluronic acid and chitosan: effects of ph, ionic strength, charge density, chain length and the charge ratio. Soft Matter. 2015;11(44):8605–12. doi: 10.1039/c5sm01829c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hendrickson ML, Rao AJ, Demerdash ON, Kalil RE. Expression of nestin by neural cells in the adult rat and human brain. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stiles J, Jernigan TL. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol Rev. 2010;20(4):327–48. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9148-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allodi I, Hedlund E. Directed midbrain and spinal cord neurogenesis from pluripotent stem cells to model development and disease in a dish. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:109. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00109. allodi, Ilary Hedlund, Eva Switzerland Front Neurosci. 2014 May 20; 8:109. doi:10.3389/fnins.2014.00109. eCollection 2014. 10.3389/fnins.2014.00109 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24904255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.