Abstract

The prevalence of cardiac diastolic dysfunction and heart failure with preserved ejection, a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the western world, is increasing due, in part, to increases in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Characteristics of cardiac diastolic dysfunction include increased myocardial stiffness and impaired left ventricular (LV) relaxation that is characterized by prolonged isovolumic LV relaxation and slow LV filling. Obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, especially in females promote activation of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) signaling with resultant increases in oxidative stress, maladaptive immune responses, inflammation, and impairment of coronary blood flow and cardiac interstitial fibrosis. This review highlights findings from the recent surge in cardiac diastolic dysfunction research. To this end it highlights our contemporary understanding of molecular mechanisms of MR regulation by genetic, epigenetic and posttranslational modifications and resultant cardiac diastolic dysfunction associated with insulin resistance, obesity and type 2 diabetes. This review also explores potential preventative and therapeutic strategies directed in the prevention of cardiac diastolic dysfunction and heart failure with preserved ejection.

Keywords: Mineralocorticoid receptors, diastolic heart failure, obesity, insulin resistance, females

Introduction

The prevalence of heart failure, a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the western world, is increasing due, in part, to increases in obesity diabetes and hypertension. A large community-based analysis of 5,881 participants from the Framingham Heart Study found that obese subjects have a doubling of the risk for heart failure [1, 2]. After adjustment for established risk factors, such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, there was an increase in the risk of heart failure of 5% for men and 7% for women for each increment of 1 in body mass index [1, 2]. Also, the Framingham Heart Study found insulin resistance increases risk of heart failure 2–8 fold in patients with diabetes [3–5]. Obesity/diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction often progresses through an initial subclinical period characterized by subtle structural and functional abnormalities, for example, diastolic relaxation through to severe diastolic heart failure with normal ejection fraction followed by systolic dysfunction accompanied by heart failure with reduced ejection fraction [6]. Thus, cardiac diastolic dysfunction (DD) is one of the early functional cardiac abnormalities observed in obesity, diabetes and associated cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is an independent risk predictor of CVD events [1, 6]. Changes in myocardial metabolism of glucose and fatty acids may be responsible for structural changes in the myocardium, such as cardiac hypertrophy, collagen deposition, and interstitial and peri-vascular fibrosis. All these structural changes lead to cardiac DD and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [6].

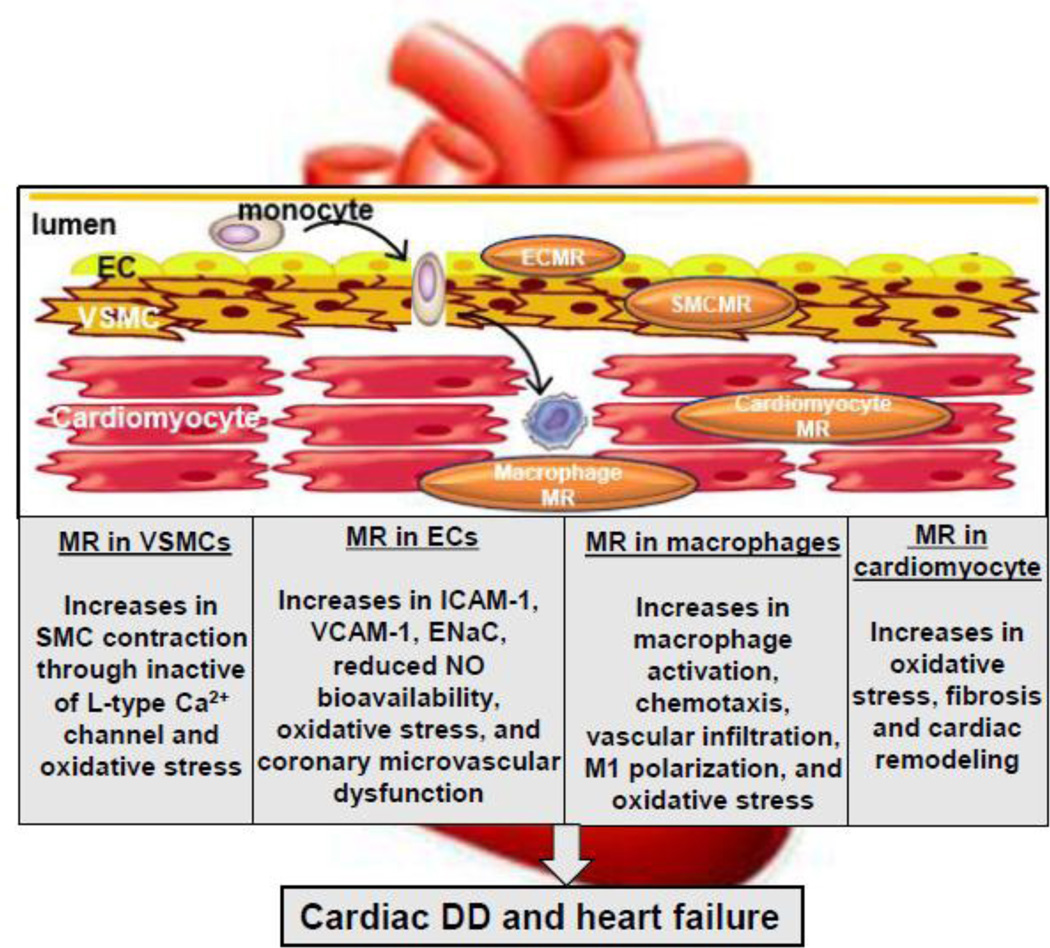

Increased activation of the renin–angiotensin– aldosterone system in states of insulin resistance and/or obesity has an important role in the pathogenesis of various CVD, including cardiac DD and heart failure [1]. Epidemiological studies support an important relationship between elevated aldosterone levels and increased risk rates of cardiovascular disease (CVD), and it is well-established that inhibitors of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activation reduce CVD events [7]. Large randomized controlled trials such as RALES, EPHESUS, and EMPHASIS have demonstrated that MR antagonist decrease mortality and morbidity in both mild and moderately severe heart failure [8]. Furthermore, a randomized, controlled clinical trials evaluated the efficacy of MR antagonists in patients with cardiac DD or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and found that MR antagonists inhibited cardiac fibrosis and improved cardiac DD, implicating MR signaling as a key contributor of cardiac DD and heart failure [9]. MRs are expressed in coronary vessel endothelial cells (ECs) and vasular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, as well as on immune cells [10, 11] (Fig. 1). Enhanced activation of MRs by aldosterone or glucocorticoids impairs insulin metabolic signaling, induces oxidative stress, induces inflammation and subsequently prompts cardiovascular abnormalities in patients with obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus who typically exhibit a high prevalence of cardiac DD [11] (Fig. 1). Research into the pathophysiology involved in the evolution of DD has demonstrated the importance of systemic and cardiac insulin resistance, impaired coronary microcirculation, oxidative stress, as well as maladaptive immune responses i, [12, 13]. However, the precise role of enhanced activation of MRs in the pathogenesis of DD in insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and obesity is still yet to be elucidated. In the present review, we will focus on recent studies examining the pathophysiological processes by which MR activation contributes to cardiac DD and CVD, as well as the contemporary understanding of potential therapeutic strategies.

Fig 1.

Depiction of molecular mechanism in the enhanced MR signaling-induced cardiac DD and heart failure. Abbreviations: MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; EC, endothelial cells; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cells; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; ENaC, epithelial sodium channel; NO, nitric oxide; DD, diastolic dysfunction.

Pathophysiology of cardiac DD

Both increased myocardial fibrosis and stiffness and impaired left ventricular (LV) relaxation with preserved ejection characterize cardiac DD. This cardiac abnormality includes prolonged isovolumic LV relaxation, slow LV filling, and increased diastolic LV stiffness [14, 15]. One factor that may be involved in DD pathology is LV hypertrophy (LVH) which increases the ratio of myocardial mass to volume, and the hypertrophy level is a critical determinant of chamber stiffness. LVH often leads to a vicious cycle of greater LV filling pressures and poor LV compliance [15]. Furthermore, a characteristic feature of diastolic heart failure with preserved ejection is slow LV relaxation, which may reduce LV stroke volume, especially at high heart rates [15]. LV relaxation is dependent on both nitric oxide (NO) signaling and sarcoplasmic reticular calcium (Ca2+) reuptake [11]. Endothelium NO synthase (eNOS) activation increases bioavailable NO which diffuses into the cardiomyocytes, interacts with soluble guanylate cyclase to generate the second messenger cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) from guanosine triphosphate (GTP). The soluble cGMP activates cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinase G (PKG) [11]. PKG, a kinase involved in phosphorylating a number of proteins, hyperpolarizes the cell membrane, regulates Ca2+ concentrations and sensitization, and causes actin filament and myosin dynamic alterations, and subsequently results in cardiomyocyte relaxation [11]. Meanwhile, NO/PKG/cGMP signaling can phosphorylate the large stiffness protein titin by changing the ratio of titin isoform N2BA:N2B expression which, in turn, decreases cardiac stiffness and improves relaxation [16]. In this regard, Titin is a sarcomeric protein that functions as a molecular spring and LV relaxation function [17]. Alternative splicing of titin isoforms gives the two isoforms: the larger and more compliant N2BA containing both N2A and N2B segments and the smaller N2B isoform containing only the N2B segment in heart [17]. Recently the titin splicing factor RBM20 was discovered to regulate cardiac function in a mouse model of heart failure [18]. Inactivating RBM20 results in upregulation of compliant titin isoforms and a large reduction in cellular passive stiffness whereas extracellular matrix (ECM)-based stiffness is unaffected [18]. These changes were associated with improvement of LV diastolic chamber compliance, concentric remodeling and exercise tolerance [18]. One study also found that an increase of cardiac titin isoforms N2BA:N2B expression ratio was present in 20 heart failure patients [19], suggesting that the ratio of cardiac titin isoforms N2B (stiffness) and large N2BA (compliant) plays a key role in cardiac compliance. Thus, alterations in titin biology can lead to both cardiac stiffness and impairment of relaxation.

Role of MR activation in cardiac DD

Aldosterone is a steroid hormone that is produced in the adrenal glomerulosa cells and fat and regulates blood pressure by acting on renal MR to promote sodium retention [20]. Aldosterone also has extra-renal actions since MR is expressed in some cardiovascular tissues including heart and vascular tissues [21, 22]. While the vascular tissue expresses the 11-betahydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2, the heart does not [21, 22]. Thus, in contrast to the vasculature both glucocorticoids and aldosterone can activate the MR in the heart. As the circulating levels pf glucocorticoids is considerably higher than aldosterone, cardiac MRs are normally activated primarily by gludcocorticoids. The classical genomic pathway of aldosterone action involves binding to cytosolic MRs and subsequent translocation to the nucleus and further regulates gene transcription and translation of proteins such as serum-and-glucocorticoid– induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1) [21]. Aldosterone also exerts rapid non-genomic effects that mediate cardiovascular tissue remodelingby activation of extracellular receptor kinase, Rho kinase, and protein kinaseC which results in increased cytosolic Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which in turn promote growth and tissue remodeling. [21, 22].

Epidemiological studies have indicated that enhanced MR activation plays a pivotal role in the development of DD [23–25]. Therefore, MR antagonists such as eplerenone and spironolactone have been suggested to be especially beneficial in the patients with cardiac DD and heart failure [26, 27]. Specific prevention or treatment strategies targeting cardiac DD in the obese an d diabetic populations have yet to emerge; however, given the role of inappropriate activation of local tissue and systemic renin angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) in the pathophysiology of obesity and diabetes-induced cardiomyopathies, a therapeutic strategy to inhibit MR activation seems appropriate [28]. However, in the recent phase III trial Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) study spironolactone treatment failed to reduce the primary composite hospitalization and mortality end points although it did reduce the rate of hospitalization in patients with diastolic heart failure [29, 30]. In this regard, interpretation of these results is impeded by broad inclusion criteria resulting in a heterogeneous patient population that could mask specific patient subgroups that may preferentially benefit from MR antagonist treatment.

Our laboratory has explored the role of MR activation in development of cardiac DD and associated cardiac structural abnormalities in rodent models including insulin resistant lean transgenic hypertensive Ren2 rats that exhibit well-characterized tissue RAAS activation and high levels of aldosterone [24, 31]. Results of these studies showed that a very low (sub-pressor) dose of spirolactone ameliorated DD, and this beneficial functional effect was associated with decreases in oxidative stress and cardiac fibrosis, but independent of blood pressure effects [32, 33]. We have also observed similar beneficial effects of very low dose spironolactone on diastolic function in obese mice consuming a diet high in saturated fat and refined carbohydrates (Bostick). These data demonstrate that MR activation plays a key role in the development of cardiac DD and heart failure in conditions like obesity where aldosterone levels are elevated.

Specific cell MR in cardiac DD

Recent studies have shown that MR-mediated cardiac pathology arises from a series of cell-specific responses obtained with the use of tissue-selective MR-null mice, including vascular endothelial cell MR KO (ECMRKO), vascular smooth muscle cell MR KO (SMCMRKO), macrophage/monocyte MR KO (MΦMRKO), and cardiomyocyte MRKO [22, 34–40] (Fig. 1). For instance, in contrast to wild type mice, in those with ECMRKO the deoxycorticosterone/salt-induced cardiac tissue fibrosis, inflammation and remodeling was prevented [35]. Our very recent findings indicate that cell specific ECMR signaling associated with consumption of excess fat and refined carbohydrates plays a key role in the activation of cardiac pro-fibrotic, inflammatory, and macrophage infiltration and polarization that lead to cardiac DD [22]. To this point, MR activation increases epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) vascular cell membrane expression/activity and activates SGK1 to promote vascular and cardiac stiffness and impaired cardiac relaxation [41]. Studies have also found that MRKO in SMCMRKO improves coronary flow reserve and LV compliance after experimental myocardial infarction [39]. Further, SMCMRKO inhibits the angiotensin II –induced and age-associated an increase in blood pressure [42], suggesting a role of SMCMR signaling in the pathogenesis of cardiac DD. It was recently demonstrated that MΦMRKO mice administered either deoxycorticosterone/salt (DOCA/salt) or NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester and salt (L-NAME)/salt) exhibit normal inflammatory cell recruitment in the heart, but lose both the typical early inflammatory response and tissue fibrosis following recruitment, as well as hypertension [37]. Thus, MΦMR regulates one or more critical processes in the recruited monocyte/macrophage population in turn to regulate the onset and development of cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. Indeed, activated MΦMR prompts MΦ M1 polarization and pro-inflammatory responses. MR signaling in myeloid dendritic cells can promote T lymphocyte cell activation and influence the T cell phenotype, thereby resulting in T lymphocyte activation and cardiac inflammatory response [43]. Meanwhile, cardiomyocyte MR is also involved in the development of cardiac fibrosis and macrophage infiltration. Previous studies have confirmed that MR deletion on cardiomyocytes resulted in increased expression of chemoattractant proteins and cytokines with upregulation of the connective tissue growth factor–transforming growth factor (TGF) β-collagen type III profibrotic pathway [36, 40]. Cardiomyocyte MRKO can also ameliorate cardiac fibrotic and inflammatory responses via a mechanism involving Ca2+/calmodulin protein kinase II activation in association with upstream alteration in expression regulation of the sodium hydrogen exchanger-1 in in acute ischemia-reperfusion model [40]. These studies demonstrate a context-dependent role of cell-specific MR signaling in development of cardiac fibrosis.

Mechanisms of MR signaling involved in the pathogenesis of cardiac DD

Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes

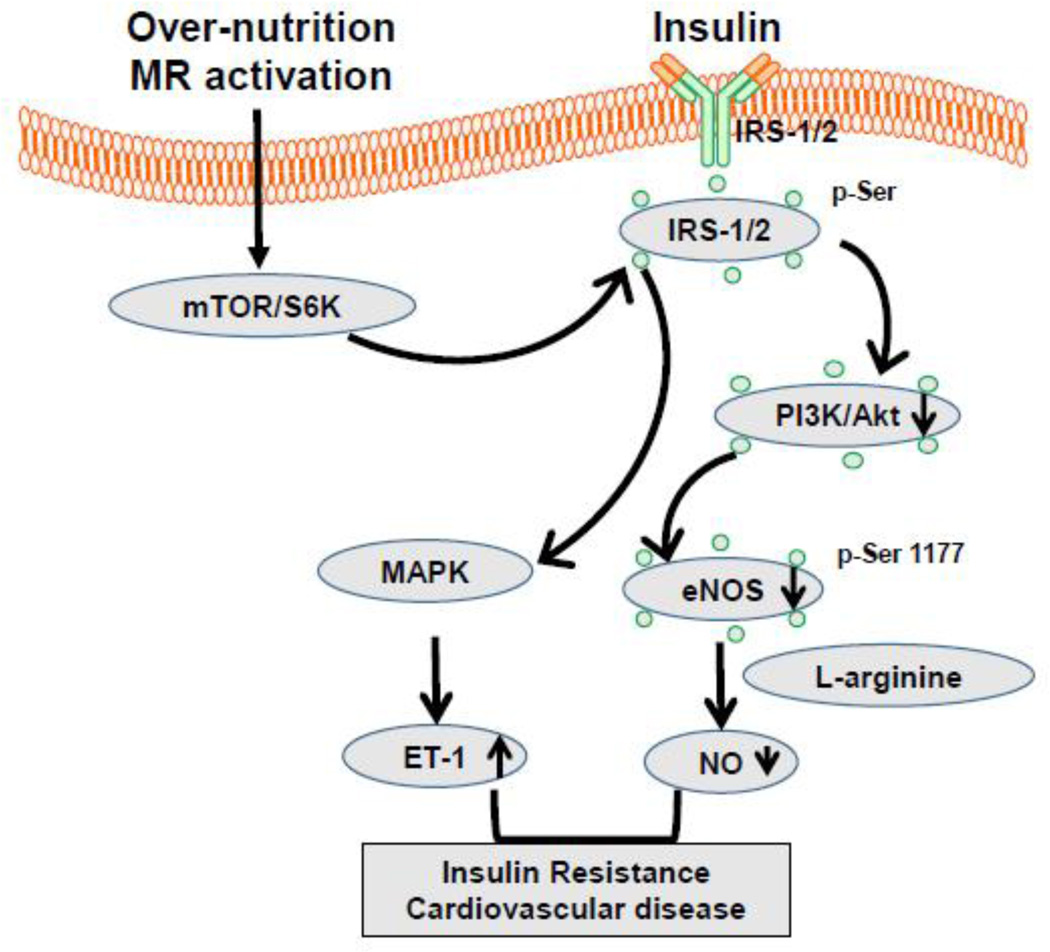

In states of insulin resistance and T2D increased activation both systemic and tissues RAAS plays an important role in the pathogenesis of CVD, including coronary artery disease (CAD) and heart failure [44–46]. The Framingham Heart Study highlighted the coexistence of diabetes and heart failure and reported that 19% of patients with heart failure have diabetes and that the risk of heart failure increases by 2–8 fold in the presence of diabetes [3–5]. In this regard, a 1% increase in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) was associated with an 8% increase in risk of cardiac dysfunction independent of blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), age, and presence of CAD suggesting that the risk of heart failure is modulated by factors unique to diabetes such as insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. [3–5]. Conversely, a 1% reduction of HbA1c is associated with a 16% reduced risk of developing cardiac dysfunction and worsening outcomes [4]. Such a bidirectional interaction between diabetes and heart failure has provided additional evidence to support the existence of a condition known as diabetic cardiomyopathy which may independently increase the risk in the development of clinical heart failure. Typically, the normal insulin metabolic signaling maintains CV dysfunction. For example, insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) tyrosine phosphorylation acts upstream of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) signal transduction pathway to elicit predominantly metabolic responses in cardiac arterial tissues [46] (Fig. 2). Activation of AKT increases the glucose uptake in the heart by translocation of glucose transporter type 4 and activate eNOS by increasing its phosphorylation. The resultant increase in bioavailable NO mediates coronary vasodilation, myocardial substrate flexibility and energy homeostasis [46]. The second pathway involves signal transduction via mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which contributes to growth and remodeling responses and the resultant myocardial hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, impaired myocardial–endothelial signaling and death of myocardial and endothelial cells (Fig. 2) [46]. Our recent work indicates that enhanced activation of the tissue RAAS may promote insulin resistance and cardiac DD through activation of the rapamycin (mTOR)/S6 kinase (S6K) signaling pathway [44–46]. For example, S6K1 is activated by angiotensin II and aldosterone in cardiovascular tissue leading to diminished insulin metabolic signaling and associated CVD, such as impaired NO-mediated coronary microvascular and cardiac relaxation [47, 48]. Moreover, increased MR activation has been found to enhance activation of both growth signaling and the pro-fibrotic TGF-β1 signaling pathways, promote proliferation, cellular differentiation, gene expression, and tissue remodeling [6, 47]. Thus, the interaction of MR activation and insulin resistance ultimately work in concert to promote cardiac fibrosis, myocardial hypertrophy, and diastolic heart failure.

Figure 2.

Proposed molecular mechanism for insulin resistance in cardiac arterial tissues. Abbreviation: mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; S6K, ribosomal S6 kinases; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3-K/Akt, phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases/protein kinase B; ET-1, endothelin-1; NO, nitric oxide; eNOS, endothelial NO synthase. IRS-1/2, insulin receptor substrate 1/2;

Oxidative stress

MR activation increases ROS, in part, by impairment of mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum function. MR activation also contributes to aldosterone-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase mediated generation of ROS in the heart and coronary microvascular. We previously reported the interaction between DD and myocardial oxidative stress in obese rodent models of insulin resistance, supporting a role oxidative stress as an important feature linking metabolic disorders to cardiac dysfunction, especially under conditions of obesity and T2D [32]. Meanwhile, the decrease in the magnitude of oxidative stress with MR antagonist treatment suggests that attenuation of MR activation prevents DD, in part, by reducing the level of oxidative stress in the myocardium. Therefore, attenuation of high caloric diet-induced MR activation and myocardial oxidative stress by MR antagonism is likely to be an important strategy contributing to the prevention of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Further, overproduction of ROS induces changes of DNA transcription and results in cellular proliferation response and alteration of some redox sensitive signaling pathways such as nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κβ) that cause cardiac tissue fibrosis, remodeling, and cardiac DD.

Maladaptive immune responses and inflammation

Cardiac DD onset and progression occurs via alterations in the innate and adaptive immune system, which is composed of diverse cellular components including granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and natural killer cells [11]. These immune mediated inflammation responses contribute to cardiac oxidative stress and coronary microvascular dysfunction, ultimately leading to cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and DD. Importantly, the MR has been implicated in these pathophysiological course. Specifically, enhanced MR signaling often prompts activation of pro-inflammatory T helper (Th) cells and macrophage polarization into classical (M1) or alternative (M2) phenotypes [44]. Macrophage polarization favoring an increases in M1 pro-inflammatory response and suppressing a M2 anti-inflammatory response occurs in obesity and insulin resistance states [47, 49]. The pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages secrete inflammatory cytokines to cause reduced systemic and cardiac insulin metabolic signaling and cardiac dysfunction [47]. In contrast, M2 macrophages lessen the development of cardiac fibrosis and protect normal cardiac function [47, 50]. Th lymphocytes have been also identified as players in MR activation-induced abnormalities [51]. For example, increased Th release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors leads to increased cardiac fibrosis and impaired diastolic relaxation. Thus, systemic and local adaptive immune responses and associated inflammation can result in impairment of coronary microvascular and cardiac DD which can progress to clinical heart failure.

Coronary microvascular dysfunction

Mechanisms that underlie the development of cardiac DD include dysfunction of the coronary microcirculation, enhanced inflammation, oxidative stress and resultant fibrosis [10]. Clinically, coronary microvascular function can be assessed by determination of coronary flow reserve (CFR), impaired CFR is a powerful independent predictor of cardiac mortality in CVD patients [52]. Coronary arterial stiffness and impaired CFR are regulated by an ECMR signaling-activated ENaC/eNOS cascade. Indeed, activation of the MR increases ENaC surface abundance, intra-endothelial Na+, actin polymerization and cell stiffness, leading to subsequent decreases in eNOS activation and bioavailable NO [11, 21]. In VSMCs, reduced NO decreases cGMP and activates kinases responsible for promotion of coronary stiffness and impairment of coronary blood flow [53]. Normally NO also modulates the phosphorylation state (P) state of myosin light chain (MLC) phosphatase to reduce MLC kinase sensitization/activation [11]. Thus both increases in VSMC levels of intracellular Ca2+ and Ca2+ sensitization induces the coronary constriction and stiffness in states of diminished insulin metabolic signaling [11]. Research has also found that bioavailability of NO is impaired by inflammation cytokines and tissue RAASactivation is associated with decreased tissue transglutaminase (TG2) S-nitrosylation and thus increased activation of this connective tissue cross-linking promoting enzyme [54], which plays an important role in cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. To this point, TG2 is particularly abundantly expressed in the CV and crosslinks several substrates, including collagen, which promotes CV fibrosis/stiffness and maladaptive remodeling [54, 55]. TG2 is largely confined to the cytosol, however a portion of it is associated with the cell membrane and secreted out of the cell to the ECM. Outside the cytosol TG-2 is activated and catalyzes the transamidation reaction [54, 55]. Normally, TG2 undergoes intracellular s-nitrosylation by NO which retains TG2 within the cytosolic compartment. Reduced NO availability, leads to TG2 translocation to the extracellular compartment to affect crosslinking of extracellular matrix proteins [54, 55]. Thus, increased secretion of TG2 to the cell surface and into the ECM and enhanced cross linking activity in cardiac tissues leads to increased fibrosis and DD.

Genetic, epigenetic and posttranslational regulation of MR

MR expression or activity may be regulated by genetic, epigenetic and posttranslational modifications. The functional MR polymorphisms have been identified to affect MR expression and activity. For example, MRI180V (rs5522) and the MR-2G/C (rs2070951) are two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the MR gene that regulate the trans-activational capacity of the MR in response to the stimulation of cortisol or dexamethasone [56]. To this point, MRI180V (rs5522) affects blood pressure response to enalapril treatment and may serve as a useful pharmacogenomic marker of antihypertensive response to enalapril in essential hypertension patients [57, 58]. The MR-2GC polymorphism is involved in the spironolactone-induced potassium level elevation in patient with heart failure [58, 59]. Epigenetic events may regulate MR activity and associated CVD. For example, DNA methylation in 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11 βHSD2) reduces activity of 11βHSD2, which leads to over-activation of the MR by cortisol with renal sodium retention, hypokalemia, and a salt-sensitive increase in blood pressure [60]. microRNAs-124 (miR-124) and miR-135a have also been found to regulate MR expression and thereby might be involved in blood pressure regulation [61]. Posttranscriptional regulation manners including phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, sumoylation, and oxidation are involved in the MR expression. In this regard, the inactive MR is located in the cytosol associated with heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) [62]. After ligand binding, the MR monomer rapidly translocates into the nucleus while still being associated to HSP90 and after dissociation from HSP90 binds to glucocorticoid response elements as a dimer [62]. Factor such as high salt, oxidative or nitrosative stress, hypothetically by induction or posttranslational modifications control the rapid MR trafficking that is relevant for both genomic and nongenomic MR effects [62]. Understanding of the genetic, epigenetic and posttranslational regulation of MR will help us to identify those individuals at high risk for heart failure and other CVD.

Gender difference in cardiac DD

Women in the postmenopausal state are more susceptible to the deleterious effects of CVD since postmenopausal women which is, in part thought to be due to has a decrease in plasma estrogen levels [63]. A consistent finding in population studies is that the number of women CVD significantly exceed that seen in men in a range of 2:1 [64]. Furthermore, CVD is strikingly increased in women with obesity and T2D [44, 65]. The Framingham Heart Study showed LV mass and wall thickness is significantly greater in women than in men with insulin resistance [66]. Moreover, aldosterone levels are higher in overweight females, and the elevated plasma aldosterone is positively associated with markers of LV hypertrophy and concentric cardiac remodeling in females but not in males [66–69]. Thus, mineralocorticoid excess and enhanced macrophage, vascular and cardiac MR signaling in obese persons, especially females, promotes cardiac, inflammation, oxidative stress, fibrosis and maladaptive cardiac remodeling.

Conclusions

This review presents extant evidence that enhanced MR signaling plays a key role in the development of cardiac DD and heart failure which is characterized by increased myocardial stiffness and impaired LV relaxation. These abnormalities are often associated with insulin resistance, T2D, oxidative stress, maladaptive immune responses and inflammation, and impairment of coronary blood flow. Females with obesity, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia represent a high risk population for development of cardiac fibrosis, maladaptive structural remodeling, DD, and heart failure. Further research is warranted to better understand the molecular biological mechanisms involved in the development of cardiac DD and progression to clinical heart failure to better enable the development of clinically effective targets for preventing cardiac DD and other CVD.

Highlights.

Activation of MR is a risk factor in the development of heart failure.

Cell specific MR mediates cardiac diastolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes.

Oxidative stress, inflammation, and interstitial fibrosis contribute to heart failure.

Genetic, epigenetic and posttranslational modifications in MR expression.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Brenda Hunter for her editorial assistance. This research was supported by NIH (R01 HL73101-01A, R01 HL107910-01) and the Veterans Affairs Merit System (0018) for JRS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Jindal A, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Obesity and heart failure as a mediator of the cerebrorenal interaction. Contrib Nephrol. 2013;179:15–23. doi: 10.1159/000346718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, Wilson PW, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Obesity and the risk of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:305–313. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maisch B, Alter P, Pankuweit S. Diabetic cardiomyopathy--fact or fiction? Herz. 2011;36:102–115. doi: 10.1007/s00059-011-3429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong AK, AlZadjali MA, Choy AM, Lang CC. Insulin resistance: a potential new target for therapy in patients with heart failure. Cardiovascular therapeutics. 2008;26:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2008.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witteles RM, Fowler MB. Insulin-resistant cardiomyopathy clinical evidence, mechanisms, and treatment options. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falcao-Pires I, Leite-Moreira AF. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: understanding the molecular and cellular basis to progress in diagnosis and treatment. Heart Fail Rev. 2012;17:325–344. doi: 10.1007/s10741-011-9257-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivanes F, Susen S, Mouquet F, Pigny P, Cuilleret F, Sautiere K, Collet JP, Beygui F, Hennache B, Ennezat PV, Juthier F, Richard F, Dallongeville J, Hillaert MA, Doevendans PA, Jude B, Bertrand M, Montalescot G, Van Belle E. Aldosterone, mortality, and acute ischaemic events in coronary artery disease patients outside the setting of acute myocardial infarction or heart failure. European heart journal. 2012;33:191–202. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen JZ, Young MJ. Corticosteroids, heart failure, and hypertension: a role for immune cells? Endocrinology. 2012;153:5692–5700. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey A, Garg S, Matulevicius SA, Shah AM, Garg J, Drazner MH, Amin A, Berry JD, Marwick TH, Marso SP, de Lemos JA, Kumbhani DJ. Effect of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists on Cardiac Structure and Function in Patients With Diastolic Dysfunction and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002137. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia G, Aroor AR, Martinez-Lemus LA, Sowers JR. Overnutrition, mTOR signaling and cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307:R1198–R1206. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00262.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia G, DeMarco VG, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2016;12:144–153. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sverdlov AL, Elezaby A, Qin F, Behring JB, Luptak I, Calamaras TD, Siwik DA, Miller EJ, Liesa M, Shirihai OS, Pimentel DR, Cohen RA, Bachschmid MM, Colucci WS. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Mediate Cardiac Structural, Functional, and Mitochondrial Consequences of Diet-Induced Metabolic Heart Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YC, Liang CS, Gopal DM, Ayalon N, Donohue C, Santhanakrishnan R, Sandhu H, Perez AJ, Downing J, Gokce N, Colucci WS, Ho JE. Preclinical Systolic and Diastolic Dysfunctions in Metabolically Healthy and Unhealthy Obese Individuals. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:897–904. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.002026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu PC, Tsai WC, Lin TH, Su HM, Voon WC, Lai WT, Sheu SH. Association of arterial stiffness and electrocardiography-determined left ventricular hypertrophy with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. PloS one. 2012;7:e49100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borlaug BA, Paulus WJ. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. European heart journal. 2011;32:670–679. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teo LY, Chan LL, Lam CS. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in hypertension. Current opinion in cardiology. 2016;31:410–416. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeWinter MM, Zile MR. Could Modification of Titin Contribute to an Answer for HFpEF? Circulation. 2016 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Methawasin M, Strom JG, Slater RE, Fernandez V, Saripalli C, Granzier HL. Experimentally Increasing Titin's Compliance Through RBM20 Inhibition Improves Diastolic Function in a Mouse Model of HFpEF. Circulation. 2016 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagueh SF, Shah G, Wu Y, Torre-Amione G, King NM, Lahmers S, Witt CC, Becker K, Labeit S, Granzier HL. Altered titin expression, myocardial stiffness, and left ventricular function in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110:155–162. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135591.37759.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sowers JR. Hypertension, angiotensin II, and oxidative stress. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1999–2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe020054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia G, Habibi J, Aroor AR, Martinez-Lemus LA, DeMarco VG, Ramirez-Perez FI, Sun Z, Hayden MR, Meininger GA, Mueller KB, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Endothelial Mineralocorticoid Receptor Mediates Diet-Induced Aortic Stiffness in Females. Circ Res. 2016;118:935–943. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.308269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia G, Habibi J, DeMarco VG, Martinez-Lemus LA, Ma L, Whaley-Connell AT, Aroor AR, Domeier TL, Zhu Y, Meininger GA, Barrett Mueller K, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Endothelial Mineralocorticoid Receptor Deletion Prevents Diet-Induced Cardiac Diastolic Dysfunction in Females. Hypertension. 2015;66:1159–1167. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bostick B, Habibi J, DeMarco VG, Jia G, Domeier TL, Lambert MD, Aroor AR, Nistala R, Bender SB, Garro M, Hayden MR, Ma L, Manrique Acevedo C, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Blockade Prevents Western Diet-induced Diastolic Dysfunction in Female Mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H1126–H1135. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00898.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habibi J, DeMarco VG, Ma L, Pulakat L, Rainey WE, Whaley-Connell AT, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade improves diastolic function independent of blood pressure reduction in a transgenic model of RAAS overexpression, American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2011;300:H1484–H1491. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01000.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bender SB, DeMarco VG, Padilla J, Jenkins NT, Habibi J, Garro M, Pulakat L, Aroor AR, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonism Treats Obesity-Associated Cardiac Diastolic Dysfunction. Hypertension. 2015:1082–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cannon JA, Collier TJ, Shen L, Swedberg K, Krum H, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Vincent J, Pocock SJ, Pitt B, Zannad F, McMurray JJ. Clinical outcomes according to QRS duration and morphology in the Eplerenone in Mild Patients: Hospitalization and SurvIval Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF) Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:707–716. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filippatos G, Anker SD, Bohm M, Gheorghiade M, Kober L, Krum H, Maggioni AP, Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Zannad F, Kim SY, Nowack C, Palombo G, Kolkhof P, Kimmeskamp-Kirschbaum N, Pieper A, Pitt B. A randomized controlled study of finerenone vs. eplerenone in patients with worsening chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus and/or chronic kidney disease. European heart journal. 2016;37:2105–2114. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sciarretta S, Paneni F, Palano F, Chin D, Tocci G, Rubattu S, Volpe M. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and inflammatory processes in the development and progression of diastolic dysfunction. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;116:467–477. doi: 10.1042/CS20080390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah AM, Shah SJ, Anand IS, Sweitzer NK, O'Meara E, Heitner JF, Sopko G, Li G, Assmann SF, McKinlay SM, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD, Investigators T. Cardiac structure and function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: baseline findings from the echocardiographic study of the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:104–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Harty B, Heitner JF, Kenwood CT, Lewis EF, O'Meara E, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, Yang S, McKinlay SM, Investigators T. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1383–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stas S, Whaley-Connell A, Habibi J, Appesh L, Hayden MR, Karuparthi PR, Qazi M, Morris EM, Cooper SA, Link CD, Stump C, Hay M, Ferrario C, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade attenuates chronic overexpression of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system stimulation of NADPH oxidase and cardiac remodeling. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3773–3780. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bender SB, DeMarco VG, Padilla J, Jenkins NT, Habibi J, Garro M, Pulakat L, Aroor AR, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism treats obesity-associated cardiac diastolic dysfunction. Hypertension. 2015;65:1082–1088. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeMarco VG, Habibi J, Jia G, Aroor AR, Ramirez-Perez FI, Martinez-Lemus LA, Bender SB, Garro M, Hayden MR, Sun Z, Meininger GA, Manrique C, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Low-Dose Mineralocorticoid Receptor Blockade Prevents Western Diet-Induced Arterial Stiffening in Female Mice. Hypertension. 2015;66:99–107. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bene NC, Alcaide P, Wortis HH, Jaffe IZ. Mineralocorticoid receptors in immune cells: emerging role in cardiovascular disease. Steroids. 2014;91:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rickard AJ, Morgan J, Chrissobolis S, Miller AA, Sobey CG, Young MJ. Endothelial cell mineralocorticoid receptors regulate deoxycorticosterone/salt-mediated cardiac remodeling and vascular reactivity but not blood pressure. Hypertension. 2014;63:1033–1040. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rickard AJ, Morgan J, Bienvenu LA, Fletcher EK, Cranston GA, Shen JZ, Reichelt ME, Delbridge LM, Young MJ. Cardiomyocyte mineralocorticoid receptors are essential for deoxycorticosterone/salt-mediated inflammation and cardiac fibrosis. Hypertension. 2012;60:1443–1450. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.203158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Usher MG, Duan SZ, Ivaschenko CY, Frieler RA, Berger S, Schutz G, Lumeng CN, Mortensen RM. Myeloid mineralocorticoid receptor controls macrophage polarization and cardiovascular hypertrophy and remodeling in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:3350–3364. doi: 10.1172/JCI41080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C, Zhang YY, Frieler RA, Zheng XJ, Zhang WC, Sun XN, Yang QZ, Ma SM, Huang B, Berger S, Wang W, Wu Y, Yu Y, Duan SZ, Mortensen RM. Myeloid mineralocorticoid receptor deficiency inhibits aortic constriction-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. PloS one. 2014;9:e110950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gueret A, Harouki N, Favre J, Galmiche G, Nicol L, Henry JP, Besnier M, Thuillez C, Richard V, Kolkhof P, Mulder P, Jaisser F, Ouvrard-Pascaud A. Vascular Smooth Muscle Mineralocorticoid Receptor Contributes to Coronary and Left Ventricular Dysfunction After Myocardial Infarction. Hypertension. 2016;67:717–723. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bienvenu LA, Reichelt ME, Morgan J, Fletcher EK, Bell JR, Rickard AJ, Delbridge LM, Young MJ. Cardiomyocyte Mineralocorticoid Receptor Activation Impairs Acute Cardiac Functional Recovery After Ischemic Insult. Hypertension. 2015;66:970–977. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tirosh A, Garg R, Adler GK. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and the metabolic syndrome. Current hypertension reports. 2010;12:252–257. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCurley A, Pires PW, Bender SB, Aronovitz M, Zhao MJ, Metzger D, Chambon P, Hill MA, Dorrance AM, Mendelsohn ME, Jaffe IZ. Direct regulation of blood pressure by smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptors. Nature medicine. 2012;18:1429–1433. doi: 10.1038/nm.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen JZ, Morgan J, Tesch GH, Rickard AJ, Chrissobolis S, Drummond GR, Fuller PJ, Young MJ. Cardiac Tissue Injury and Remodeling Is Dependent Upon MR Regulation of Activation Pathways in Cardiac Tissue Macrophages. Endocrinology. 2016;157:3213–3223. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, Sowers JR. The pathophysiology of hypertension in patients with obesity. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2014;10:364–376. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nistala R, Sowers JR. Hypertension: Synergy of antihypertensives in elderly patients with CKD. Nature reviews. Nephrology. 2013;9:13–15. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jia G, Aroor AR, Martinez-Lemus LA, Sowers JR. Overnutrition, mTOR signaling, and cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307:R1198–R1206. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00262.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jia G, Habibi J, Bostick BP, Ma L, DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, Hayden MR, Whaley-Connell AT, Sowers JR. Uric acid promotes left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in mice fed a Western diet. Hypertension. 2015;65:531–539. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim JA, Jang HJ, Martinez-Lemus LA, Sowers JR. Activation of mTOR/p70S6 kinase by ANG II inhibits insulin-stimulated endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vasodilation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E201–E208. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00497.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mori J, Alrob OA, Wagg CS, Harris RA, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. ANG IIcauses insulin resistance and induces cardiac metabolic switch, inefficiency: a critical role of PDK4, American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2013;304:H1103–H1113. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00636.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asrih M, Mach F, Nencioni A, Dallegri F, Quercioli A, Montecucco F. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in multifactorial adverse cardiac remodeling associated with metabolic syndrome. Mediators of inflammation. 2013;2013:367245. doi: 10.1155/2013/367245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weirather J, Hofmann UD, Beyersdorf N, Ramos GC, Vogel B, Frey A, Ertl G, Kerkau T, Frantz S. Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells improve healing after myocardial infarction by modulating monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Circulation research. 2014;115:55–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ikonomidis I, Lambadiari V, Pavlidis G, Koukoulis C, Kousathana F, Varoudi M, Spanoudi F, Maratou E, Parissis J, Triantafyllidi H, Paraskevaidis I, Dimitriadis G, Lekakis J. Insulin resistance and acute glucose changes determine arterial elastic properties and coronary flow reserve in dysglycaemic and first-degree relatives of diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayden MR, Habibi J, Joginpally T, Karuparthi PR, Sowers JR. Ultrastructure Study of Transgenic Ren2 Rat Aorta - Part 1: Endothelium and Intima. Cardiorenal medicine. 2012;2:66–82. doi: 10.1159/000335565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Staiculescu MC, Foote CA, Polo-Parada L, Martinez-Lemus LA. The obligatory role of the actin cytoskeleton on inward remodeling induced by dithiothreitol activation of endogenous transglutaminase in isolated arterioles American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2014;306:H485–H495. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00557.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Staiculescu MC, Foote C. L.A. Martinez-Lemus, Mechanisms of the inward remodeling process in resistance vessels: is the actin cytoskeleton involved? Microcirculation. 2014;21:219–229. doi: 10.1111/micc.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Leeuwen N, Kumsta R, Entringer S, de Kloet ER, Zitman FG, DeRijk RH, Wust S. Functional mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) gene variation influences the cortisol awakening response after dexamethasone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo JQ, Wang LY, He FZ, Sun NL, Tang GF, Wen JG, Luo ZY, Liu ZQ, Zhou HH, Chen XP, Zhang W. Effect of NR3C2 genetic polymorphisms on the blood pressure response to enalapril treatment. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:201–208. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jaisser F, Farman N. Emerging Roles of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor in Pathology: Toward New Paradigms in Clinical Pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:49–75. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cavallari LH, Groo VL, Viana MA, Dai Y, Patel SR, Stamos TD. Association of aldosterone concentration and mineralocorticoid receptor genotype with potassium response to spironolactone in patients with heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:1–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alikhani-Koopaei R, Fouladkou F, Frey FJ, Frey BM. Epigenetic regulation of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 expression. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1146–1157. doi: 10.1172/JCI21647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sober S, Laan M, Annilo T. MicroRNAs miR-124 and miR-135a are potential regulators of the mineralocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C2) expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:727–732. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gekle M, Bretschneider M, Meinel S, Ruhs S, Grossmann C. Rapid mineralocorticoid receptor trafficking. Steroids. 2014;81:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duprez D, Jacobs DR., Jr Arterial stiffness and left ventricular diastolic function: does sex matter? Hypertension. 2012;60:283–284. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Brokat S, Tschope C. Role of gender in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;49:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mosca L, Manson JE, Sutherland SE, Langer RD, Manolio T, Barrett-Connor E. Cardiovascular disease in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Writing Group, Circulation. 1997;96:2468–2482. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rutter MK, Parise H, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Larson MG, Meigs JB, Nesto RW, Wilson PW, Vasan RS. Impact of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance on cardiac structure and function: sex-related differences in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:448–454. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000045671.62860.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manrique C, DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, Mugerfeld I, Garro M, Habibi J, Hayden MR, Sowers JR. Obesity and insulin resistance induce early development of diastolic dysfunction in young female mice fed a Western diet. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3632–3642. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mihailidou AS, Ashton AW. Cardiac effects of aldosterone: does gender matter? Steroids. 2014;91:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vasan RS, Evans JC, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Larson MG, Sundstrom J, Murabito JM, Sam F, Colucci WS, Wilson PW. Relations of serum aldosterone to cardiac structure: gender-related differences in the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 2004;43:957–962. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000124251.06056.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]