Abstract

A synaptic pool of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) controls synaptic transmission, although little is known about its underlying signaling mechanisms. Here, we found that synaptic ERK2 directly binds to postsynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a (mGluR1a). This binding is direct and the ERK-binding site is located in the intracellular C-terminus (CT) of mGluR1a. Parallel with this binding, ERK2 phosphorylates mGluR1a at a cluster of serine residues in the distal part of mGluR1a-CT. In rat cerebellar neurons, ERK2 interacts with mGluR1a at synaptic sites, and active ERK constitutively phosphorylates mGluR1a under normal conditions. This basal phosphorylation is critical for maintaining adequate surface expression of mGluR1a. ERK is also essential for controlling mGluR1a signaling in triggering distinct postreceptor signaling transduction pathways. In summary, we have demonstrated that mGluR1a is a sufficient substrate of ERK2. ERK that interacts with and phosphorylates mGluR1a is involved in the regulation of the trafficking and signaling of mGluR1.

Keywords: Cerebellum, mGluR, G protein-coupled receptor, MAPK, IP3, Src, Phosphorylation

Introduction

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) and are densely expressed in mammalian brains. Through activating diverse postreceptor signaling pathways, mGluRs regulate synaptic transmission at both pre- and postsynaptic sites [1, 2]. As essential glutamate receptors, abnormal mGluR activity has been linked to a variety of neuropsychiatric, neurodegenerative, and cognitive disorders [2, 3]. Recent studies focus on group I mGluRs (mGluR1 and mGluR5 subtypes). These subtypes are coupled to phospholipase Cβ1 (PLCβ1) through Gαq proteins. Activating them increases PLCβ1-mediated phosphoinositide hydrolysis, yielding diacylglycerol and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) to trigger protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca2+ signaling pathways, respectively. mGluR1/5 are mostly peri- and post-synaptic [4, 5] and act as prime regulators in the postsynaptic density (PSD) microdomain to control strength and efficacy of excitatory synapses.

The mGluR1 subtype, as a typical GPCR, has a C-terminal tail protruding intracellularly. This C-terminus (CT) is large in size, and a long-form splice variant (mGluR1a) CT contains a total of 359 amino acids. This long CT makes mGluR1a readily accessible to various submembranous binding partners [6, 7]. Through direct protein–protein interactions, mGluR1a-associated proteins regulate subcellular and subsynaptic distributions and efficacy of the receptor [6, 7]. One noticeable group of mGluR1a-associated regulators is protein kinases. These kinases interact with and phosphorylate mGluR1a CT and thereby modulate mGluR1a [8, 9], although the responsible kinases and detailed phosphorylation-dependent mechanisms are less clear at present.

A prototypical mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family member, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), is expressed in adult brain postmitotic neurons. Once activated by MAPK kinase (MEK), ERK translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to phosphorylate discrete transcription factors, including Elk-1, to alter gene expression and transcriptionally regulate synaptic transmission and plasticity [10–12]. Additionally, ERK and phosphorylated ERK (pERK, active form) are notably present in neuronal peripheral structures, such as dendritic spines and synaptic zones [13–16]. ERK, predominantly the ERK2 isoform, and all MAPK cascade components colocalize within the PSD [17, 18]. While this synaptic pool of ERK is thought to serve as a local regulator, little is known about their specific substrates and their roles in the phosphorylation-dependent modulation of synaptic substrates [reviewed in ref. 19].

To search for a new substrate of ERK at synaptic sites, we found that ERK2 directly binds to mGluR1a CT. Active ERK2 phosphorylates a cluster of serine residues in the distal part of mGluR1a CT. Endogenous ERK2 forms complexes with mGluR1a in the synaptic compartment of rat cerebellar neurons, which enables ERK2 to phosphorylate mGluR1a and facilitate surface trafficking and signaling efficacy of the receptor. Together, we have discovered an ERK2-mediated mechanism underlying the regulation of mGluR1a.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male Wistar rats from Charles River (New York, NY) were used in this study. Animals were individually housed at 23 °C and humidity of 50 ± 10 % with food and water available ad libitum. The animal room was on a 12-/ 12-h light/dark cycle with lights on at 0700. All animal use procedures were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Synthesis of Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST)-Fusion Proteins

We synthesized GST-fusion proteins containing full-length (FL) or truncated proteins of interest according to the method described previously [20, 21]. Briefly, the cDNA fragments encoding the mGluR1a-CT1(K841-T1000), mGluR1a-CT2(P1001-L1199), mGluR1a-CT1a(K841-N885), mGluR1a-CT1b(A886-K931), mGluR1a-CT1c(N925-T1000), mGluR1a intracellular loop 1 [mGluR1a-IL1(L616-E629)], mGluR1a-IL2(R681-Q706), and mGluR1a-IL3(K773-K785) were generated by polymerase chain reaction amplification from FL cDNA clones (rat mGluR1 UniProtKB accession no. P23385). These cDNAs were subcloned into BamHI-EcoRI sites of the pGEX4T-3 plasmid (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Constructs were sequenced to confirm appropriate splice fusion. GST-fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells and purified as described by the manufacturer.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blots were performed as described previously [22]. Briefly, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) NuPAGE Bis-Tris 4–12 % gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used to separate proteins. Separated proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (see below) overnight at 4 °C and followed by secondary antibody incubation. Immunoblots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare).

In Vitro Binding Assay

This assay was carried out according to our previous work [20, 22]. Briefly, His-tagged active ERK2-FL with pT185/pY187 (Millipore, Billerica, MA; 20 ng) or His-tagged inactive ERK2-FL (Millipore; 20 ng) was equilibrated to binding buffer containing 200 mM NaCl, 0.2 % Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 50 mM Tris, pH, 7.5. Binding reactions were initiated by adding purified GST-fusion proteins and continued for 2–3 h at 4 °C. Glutathione sepharose 4B beads (10 %, 100 µl) were used to precipitate GST-fusion proteins. The precipitate was washed three times. Bound proteins were eluted with 4X lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) loading buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with antibodies indicated.

Phosphorylation Reactions In Vitro

GST or GST-fusion proteins were incubated with GST-tagged active ERK2 (Millipore, 25 ng) or GST- or His-tagged inactive ERK2 (Millipore, 25 ng) for 30 min at 30 °C in a reaction buffer (25 µl) containing 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 50 µM ATP, and 2.5 µCi/tube [γ-32P]ATP (~3000 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) with an Elk-1 fusion protein (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Elk-1 (Human, 428 amino acids, UniProtKB accession no. P19419) is a classical substrate of ERK2 and is phosphorylated by ERK2 at multiple sites, including the preferred sites of serine 383 and serine 389. These sites involve SP, TP, and PXSP phosphomotifs (where X is any amino acid) [23, 24]. We stopped the phosphorylation reactions by adding the LDS sample buffer and boiling for 3 min. Phosphorylated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography or immunoblot.

Dephosphorylation Reactions

To dephosphorylate GST-fusion proteins, we incubated GST-fusion proteins with Histagged active ERK2 (Millipore, 25 ng) in 25 µl reaction buffer containing 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT, 50 µM ATP, and 2.5 µCi/tube [γ-32P]ATP (~3000 Ci/mmol) for 30 min at 30 °C. GST-fusion proteins were precipitated and the supernatant containing ERK2 was removed. Precipitates were washed twice. They were then suspended in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ZnCl2, and calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIP, 100 units/ml; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. To dephosphorylate immunoprecipitated mGluR1a, immunocomplexes were washed with 1X NEBuffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) supplemented with 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride, 0.5 µg/ml leupeptin, 1 µg/ml pepstatin, and 0.5 µg/ml aprotinin. The beads were then divided into two tubes, and λ-protein phosphatase (200–400 units, New England Biolabs), a serine/threonine/tyrosine dual phosphatase, was added to one of tubes. Both tubes were incubated for 1 h at 30 °C. The dephosphorylation reaction was stopped by adding an LDS sample buffer. Samples were then subjected to standard gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

Phosphoamino Acid Analysis

Phosphoamino acid analysis was carried out as described previously [25]. The 32P-incorporated (phosphorylated) proteins on an SDS-PAGE gel were transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was stained and the targeted band containing a protein of interest was cut. The 32P-labeled phosphoprotein was hydrolyzed into individual amino acids in 6 N HCl (110 °C, 2 h). Hydrolysates were concentrated and spotted onto glass-backed thin-layer chromatography cellulose plates (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), along with phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, and phosphotyrosine standards. The phosphoamino acids were separated by electrophoresis in pH 3.5 buffer (5 % v/v acetic acid, 0.5 % v/v pyridine, 100 ml) in a flatbed Multiphor II electrophoresis apparatus (GE Healthcare) at 1000 V (30 mA) for 45 min. The phosphoamino acid standards were visualized with ninhydrin. The plate was exposed to X-ray film to visualize 32P-labeled amino acids.

Coimmunoprecipitation

We performed coimmunoprecipitation with rat brains as described previously [22]. After rats were anesthetized and decapitated, brains were removed. The cerebellum was homogenized in cold isotonic sucrose homogenization buffer containing 0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Rochester, NY). Homogenates were centrifuged at 800×g for 10 min at 4 °C. P2 pellets (synaptosomal fraction) were obtained by centrifuging the supernatant for 15 min (10,000×g) at 4 °C. Washed P2 was resuspended in the sucrose homogenization buffer containing Triton X-100 (0.5 %, v/v). The suspension was lysed and incubated with gentle rotation for 20 min at 4 °C. Samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 32,000×g to yield the pellet enriched with synaptic membranes. These pellets were solubilized in sucrose-Triton buffer containing 1 % sodium deoxycholate and a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail for 1 h at 4 °C. Solubilized proteins were incubated with a rabbit antibody against ERK1/2 or mGluR1a. The complex was precipitated with 50 % protein A or G agarose/sepharose bead slurry (GE Healthcare). Proteins were separated on Novex 4–12 % gels and probed with a mouse antibody against ERK1/2 or mGluR1a.

Cerebellar Slice Preparation

Rats were decapitated after anesthesia with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg). Brains were removed and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 10 glucose, 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 MgSO4, and 2 CaCl2, bubbled with 95 % O2–5 % CO2, pH 7.4. Coronal slices were cut using a VT1200S vibratome (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL). Slices were preincubated in ACSF in an incubation tube at 30 °C under constant oxygenation with 95 % O2–5 % CO2 for 1 h. The solution was replaced with fresh ACSF for an additional preincubation (10– 20 min). Drugs were added and incubated at 30 °C. After drug treatment, slices were collected for neurochemical assays.

Surface Crosslinking Assays

This was performed as described previously [26]. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg, i.p.) and decapitated. The cerebellum was cut into coronal sections (400 µm) with a vibratome. Sections were added into Eppendorf tubes containing ice-cold ACSF. We then added a bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3) reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) to 2 mM. Sections were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. The crosslinking reaction was terminated by quenching with 20 mM of glycine (10 min, 4 °C). After sections were washed four times in cold phosphate-buffered saline solutions (5 min each), they were sonicated in isotonic sucrose homogenization buffer containing 0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 % SDS, and a protease/ phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo). Proteins were saved in −80 °C before used in immunoblot analysis.

IP3 Assays

Cellular IP3 levels were measured in rat cerebellar slices using a HitHunter IP3 Fluorescence Polarization Assay Kit from DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA) or a rat IP3 ELISA Kit from CUSABIO (Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [22, 27, 28].

Antibodies and Pharmacological Agents

Antibodies used in this study include rabbit antibodies against mGluR1a (Millipore; 1:2000), ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling; 1:2000), pERK1/2 (phosphorylation at T185/Y187 for pERK2; Cell Signaling; 1:1000), GST (Sigma; 1:2000), a phospho-serine/ threonine-proline motif (pS/TP, Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:1000), a phospho-MAPK motif PXpSP or pSPXR/K (Cell Signaling; 1:1000), phosphoserine (Invitrogen; 1:1000), phosphothreonine (Invitrogen; 1:1000), Src with phosphorylated tyrosine 416 (pY416, Cell Signaling; 1:1000), Src (Cell Signaling; 1:2000), or actin (Sigma; 1:4000) or mouse antibodies against mGluR1a (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ; 1:2000), ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling; 1:2000), ERK2 (Abcam; 1:2000), or a phosphothreonine-proline motif (pTP, Cell Signaling; 1:1000). The anti-pY416 antibody reacts with the Src family members when phosphorylated at the conserved activation residue Y416. Pharmacological agents, including (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), 3-methyl-aminothiophene dicarboxylic acid (3-MATIDA), and 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[2-aminophenylthio]butadiene (U0126), were purchased from Tocris Cookson Inc. (Ballwin, MO). All drugs were freshly prepared at the day of experiments.

Statistics

The results are presented as means ± SEM. Data were evaluated using Student’s t test or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni (Dunn) comparison of groups using least-squares-adjusted means. Probability levels of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

ERK2 Phosphorylates mGluR1a

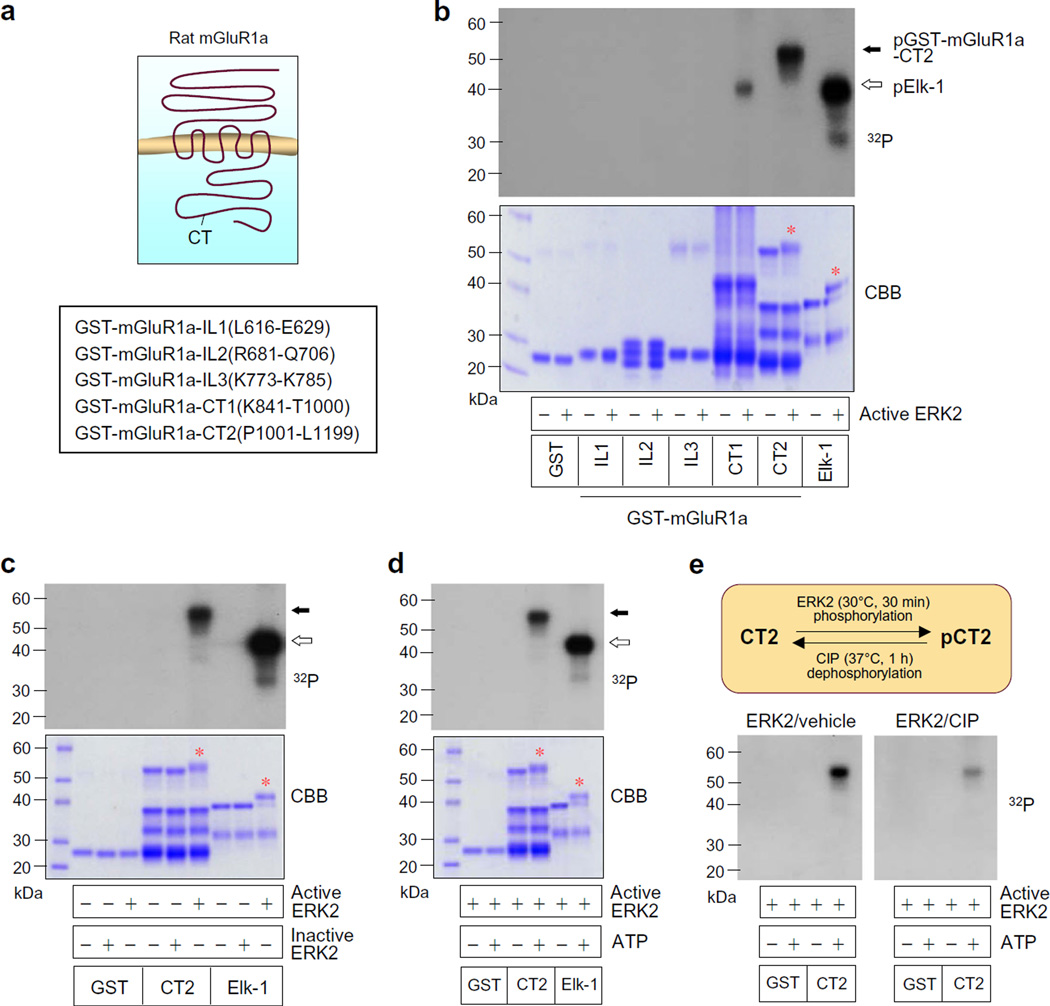

To determine whether ERK2 phosphorylates mGluR1a, we synthesized a panel of GST-fusion proteins containing confined intracellular domains of mGluR1a (Fig. 1a). We then monitored the incorporation of 32P into these domains following addition of active form of ERK2 and the phosphate donor ATP in sensitive autoradiography. Active ERK2 strongly phosphorylated GST-mGluR1a-CT2, while ERK2 did not phosphorylate GST alone and three intracellular loops (IL1, IL2, and IL3) (Fig. 1b). GST-mGluR1a-CT1 only showed a weak response to ERK2. A known prototypic substrate of ERK2, Elk-1 that is phosphorylated by ERK2 at multiple sites [23, 24], was also phosphorylated and served as a positive control. In contrast to active ERK2, inactive ERK2 failed to phosphorylate CT2 and Elk-1 (Fig. 1c). In the absence of ATP, ERK2 did not induce phosphorylation signals from either CT2 or Elk-1 (Fig. 1d). The ERK2-induced CT2 phosphorylation was subjected to dephosphorylation by a phosphatase CIP [29, 30]. As shown in Fig. 1e, application of CIP to a duplicate reaction significantly reduced the ERK-induced CT2 phosphorylation. These data demonstrate that mGluR1a serves as a sufficient phosphorylation substrate of ERK2. Primary phosphorylation site(s) seem to reside within the distal region of mGluR1a CT.

Fig. 1.

ERK2-mediated phosphorylation of mGluR1a. a GST-fusion proteins containing distinct intracellular domains of rat mGluR1a. b A representative autoradiograph illustrating the ERK2-induced phosphorylation of GST-mGluR1a-CT2 and Elk-1 but not GST and other mGluR1a fragments. A gel staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) was present below to show protein loading. Note that the CT2 segment was markedly phosphorylated by ERK2. c A representative autoradiograph above a CBB staining illustrating phosphorylation of GST-mGluR1a-CT2 by active but not inactive ERK2. d A representative autoradiograph above a CBB staining illustrating phosphorylation of GST-mGluR1a-CT2 in the presence but not absence of ATP. e CIP-mediated dephosphorylation of ERK2-phosphorylated GST-mGluR1a-CT2. All phosphorylation reactions were carried out at 30 °C for 30 min (b–e) followed by dephosphorylation reactions (e). The reactions were then subjected to gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography. Solid and open arrows indicate phosphorylated GST-mGluR1a-CT2 (pGST-mGluR1a-CT2) and Elk-1, respectively. Red stars in CBB staining images (b–d) indicate the CT2 and Elk-1 bands that were phosphorylated by ERK2. Note that these bands smeared and shifted upward as a result of slower migration due to phosphorylation

ERK2 Phosphorylates mGluR1a at Serine Sites

We next set forth to identify accurate phosphorylation sites in mGluR1a CT2. ERK2 is a serine/threonine kinase and catalyzes a consensus phosphorylation motif, S/TP [31]. Sequence analysis revealed a total of eight sites in CT2 consistent with the ERK phosphorylation motif (Fig. 2a). To identify phospho-accepting site(s) among them, we conducted phosphoamino acid analysis to define the type of amino acids that is phosphorylated by ERK2. As shown in Fig. 2b, serine sites in mGluR1a-CT2 were phosphorylated by active ERK2, while threonine was not. Moreover, phosphorylation of CT2 was visualized by a phosphomotif-specific antibody against pS/TP (Fig. 2c) but not pTP (Fig. 2d). Thus, serine rather than threonine sites in mGluR1a-CT2 are phosphorylated by ERK2. To identify accurate serine site(s), we synthesized a battery of site-directed CT2 mutants (Fig. 2e). We compared these mutants with wild-type (WT) CT2 in their phosphorylation responses to ERK2. Mutating threonine (T1064) and serine (S1098) to alanine (mutation 1: T/S1–2A) had minimal impact on CT2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2f). Mutations of the first four T/S sites (mutation 2: T/S1–4A) reduced CT2 phosphorylation. Further reduction of CT2 phosphorylation seemed to occur after mutations of the first six sites (mutation 3: T/S1–6A), while weak phosphorylation signals still remained. Mutations of all four serines (S1098, S1147, S1154, and S1169, mutation 4) caused a complete loss of phosphorylation, while mutations of all four threonines (T1064, T1143, T1151, and T1178, mutation 5) had little impact. These results indicate that a cluster of serine residues in distal CT2, including S1147, S1154, and S1169, are among the preferred sites phosphorylated by ERK2. In addition, we noticed that amino acids flanking two phosphorylation sites (S1154 and S1169) align well with the common ERK phosphorylation motif of PXpSP. We thus assessed CT2 phosphorylation using a phosphomotif-specific antibody against PXpSP. The phosphorylation of mGluR1a-CT2 by ERK2 was in fact detected by the antibody (Fig. 2g). Same results were seen with Elk-1 (Fig. 2g). Elk-1 is known to contain the ERK2-specific PXpSP motifs [23, 24].

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation of mGluR1a-CT2 by ERK2. a Amino acid sequence analysis of mGluR1a-CT2(P1001-L1199). Eight ERK2 phosphorylation motifs (T/SP) are highlighted in red. Potential phosphorylation sites include T1064 (1), S1098 (2), T1143 (3), S1147 (4), T1151 (5), S1154 (6), S1169 (7), and T1178 (8). b A representative phosphoamino acid analysis showing GST-mGluR1a-CT2 phosphorylation at serine (pSer), but not threonine (pThr) and tyrosine (pTyr), residues. c, d Phosphorylation of mGluR1a-CT2 at pS/TP (c) and pTP (d) motifs by active ERK2. e Five mutants (M1–5) derived from mGluR1a-CT2(P1001-L1199). Site-directed mutants include mutations of T1064/S1098 to alanines (M1), T1064/S1098/T1143/S1147 to alanines (M2), T1064/S1098/T1143/S1147/T1151/S1154 to alanines (M3), four serines (S1098/S1147/S1154/S1169) to alanines (M4), and four threonines (T1064/T1143/T1151/T1178) to alanines (M5). e Phosphorylation of mGluR1a-CT2 mutants and WT at pS/TP by active ERK2. Note that no signal was detected in the M4 mutant. g Phosphorylation of GST-mGluR1a-CT2 and Elk-1 at PXpSP by active ERK2. Phosphorylation of CT2 and Elk-1 was detected by immunoblot (IB) with a phosphomotif antibody against pS/TP (c, f), pTP (d), or PXpSP (g)

ERK2 Binds to mGluR1a

To determine whether ERK2 binds to mGluR1a, we carried out a series of in vitro binding assays in which GST-fusion proteins were used as immobilized molecules to capture (precipitate) binding partners. GST-mGluR1a-CT1 precipitated inactive ERK2, while GST did not (Fig. 3a). Other GST-fusion proteins containing IL1, IL2, IL3, or CT2 precipitated an undetectable amount of ERK2 proteins. Similar to inactive ERK2, active ERK2 was precipitated by GST-mGluR1a-CT1 (Fig. 3b). These data reveal that ERK2 possesses the ability to bind to mGluR1a at its CT1 region. We next tried to map a key binding site in CT1. To this end, we synthesized GST-fusion proteins containing different fragments of CT1 (CT1a-c; Fig. 3c). We found that mGluR1a-CT1a(K841-N885) precipitated inactive and active ERK2 to an extent similar to CT1 (Fig. 3d, e). In contrast, neither mGluR1a-CT1b(A886-K931) nor mGluR1a-CT1c(N925-T1000) bound to inactive or active ERK2. Thus, the CT1a region (the first 45 amino acids in the membrane proximal segment of CT) contains a core ERK2 binding site. All blots were probed in parallel with a GST antibody to ensure equivalent protein loading (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

ERK2 binding to mGluR1a. a In vitro binding assays with immobilized GST-fusion proteins containing distinct intracellular domains of mGluR1a and purified ERK2. Inactive ERK2 proteins were used in these assays. The inactive state of ERK2 was confirmed by the lack of phosphorylation signals from ERK2 proteins when tested in immunoblots (IB) with a phospho-specific antibody against pERK1/2. b In vitro binding assays with immobilized mGluR1a CT1 fragments and inactive or active ERK2. c GST-fusion proteins containing different fragments of mGluR1a CT1. d, e In vitro binding assays with immobilized GST-fusion mGluR1a-CT1a–c proteins and inactive (d) or active (e) ERK2. Note that CT1a but not CT1b and CT1c precipitated ERK2 and pERK2. ERK2 and pERK2 proteins bound to GST-fusion proteins were visualized with immunoblots using the specific antibodies against ERK2 and pERK1/2, respectively

ERK2 Interacts with mGluR1a in Neurons In Vivo

We next explored whether native ERK2 and mGluR1a interact with each other in neurons in vivo. We chose the cerebellum from rat brains for this test because mGluR1 is richly expressed, while mGluR5 is almost lacking, in this region [32, 33]. Moreover, mGluR1a is a predominant splice variant in Purkinje neurons, the principal neurons of the cerebellar cortex [34]. Previously, mGluR1a but not mGluR5 was seen in immunoblots using cerebellar whole-cell lysates or membrane samples [33]. In this study, we utilized a defined pool of synaptic plasma membranes. We observed that mGluR1a was present in the cerebellum at a level much higher than that in the striatum (Fig. 4a). In contrast, mGluR5 was expressed in the striatum but nearly absent in the cerebellum (Fig. 4b). A major functional form of mGluR1 and 5 was seen as dimers in cerebellar and striatal neurons, similar to those observed previously [35, 36]. As to ERK, a sub-pool of ERK resides in neuronal peripheral structures, such as postsynaptic dendritic spines [13, 14, 37]. A major ERK2 band was found at synaptic sites in rat striatal and prefrontal cortical neurons [16]. To determine the synaptic distribution of ERK in cerebellar neurons, we assayed the abundance of ERK1/2 in synaptic samples. A higher level of ERK2 than ERK1 proteins was shown in cerebellar synaptic membranes (Fig. 4c). The same isoform gradient was seen for pERK1/2 (Fig. 4d). Thus, like other brain regions, cerebellar neurons accommodate ERK2 as a major ERK isoform in the synaptic compartment.

Fig. 4.

Interactions of ERK2 with mGluR1a in rat cerebellar neurons. a, b Immunoblot detection of mGluR1a (a) and mGluR5 (b) proteins in synaptic membranes extracted from the cerebellum and striatum. Note that a smaller amount of cerebellar proteins (2.5 µg) than that of striatal proteins (25 µg) was loaded (a). Major dimer bands around 250 kDa and weak monomer bands (130–140 kDa) were seen for mGluR1a in the cerebellum and striatum, while mGluR5 bands (mainly dimers) were seen in the striatum but not cerebellum. c, d Immunoblot detection of ERK1/2 (c) and pERK1/2 (d) proteins in whole-cell homogenates and synaptic plasma membranes of cerebellar neurons (12.5 µg per lane). Note that ERK2 and pERK2 were expressed at a higher level than respective ERK1 and pERK1 in synaptic locations. e Coimmunoprecipitation (IP) assays of ERK1/2 and mGluR1a with the anti-mGluR1a antibody (Ab). Note that ERK2 clearly existed in mGluR1a precipitates (lane 5). Lanes 3 and 4 showed no specific bands due to the lack of a precipitating antibody (L3) and the use of an irrelevant IgG (L4). f Reverse coimmunoprecipitation assays of ERK1/2 and mGluR1a with the anti-ERK1/2 antibody. g Coimmunoprecipitation of pERK1/2 and mGluR1a. Synaptic proteins solubilized from enriched synaptic plasma membranes of the rat cerebellum were used in above IP assays. Precipitated proteins were visualized by immunoblots (IB) with indicated antibodies

To determine whether synaptic ERK2 interacts with mGluR1a in cerebellar neurons, we performed coimmunoprecipitation with solubilized cerebellar synaptic samples enriched with ERK2 and mGluR1a. In coimmunoprecipitation with an anti-mGluR1a antibody, a major ERK2 band was revealed in mGluR1a precipitates (Fig. 4e). In reverse coimmunoprecipitation, mGluR1a immunoreactive proteins existed in ERK1/2 precipitates (Fig. 4f). In mGluR1a precipitates, active pERK2 signals were predominant (Fig. 4g). Thus, endogenous ERK2 and mGluR1a interact with each other within the synapse of cerebellar neurons in vivo.

Phosphorylation of Cerebellar mGluR1a by ERK

To investigate ERK-mediated phosphorylation of mGluR1a in cerebellar neurons, we purified mGluR1a from solubilized synaptic membranes of cerebellar tissue through immunoprecipitation. We then measured the phosphorylation level of immunopurified mGluR1a at ERK-preferred phosphomotifs, such as S/TP, TP, and PXSP, using phosphomotif antibodies. Phosphorylation signals were detected in mGluR1a using an anti-pS/TP antibody (Fig. 5a). Phosphorylation at the TP motif was however weak in mGluR1a (Fig. 5b). The PXpSP phosphomotif antibody has demonstrated an ERK2-mediated phosphorylation of recombinant mGluR1a CT2 in in vitro assays above. Consistent with this, strong PXpSP signals were seen in precipitates of native mGluR1a (Fig. 5c). The phosphorylation of mGluR1a PXSP was subjected to dephosphorylation. A serine/ threonine/tyrosine dual phosphatase, λ-protein phosphatase (1 h), selectively eliminated the PXSP phosphorylation, without altering the total mGluR1a immunoreac-tivity (Fig. 5d). These data suggest that mGluR1a is likely a MAPK/ERK substrate in synapses of cerebellar neurons and is normally phosphorylated by the kinase. To confirm this, we evaluated the impact of ERK inhibition on motif phosphorylation of mGluR1a. We used an MEK inhibitor U0126 which inhibits MEK activation of ERK. Adding U0126 to rat cerebellar slices (0.5 or 5 µM, 30 min), significantly reduced PXSP phosphorylation of immunopurified mGluR1a (Fig. 5e, f). U0126 had no effect on TP phosphorylation (Fig. 5e, g). These results are consistent with the notion that ERK causes basal phosphorylation of mGluR1a. The finding that U0126 simultaneously reduced the amount of pERK2 and ERK2 coimmunoprecipitated with mGluR1a is noteworthy (Fig. 5e, h). This indicates that inhibition of ERK reduces the interaction rate of pERK2 and ERK2 with mGluR1a.

Fig. 5.

ERK-mediated phosphorylation of mGluR1a in rat cerebellar neurons. a–c Phosphorylation of mGluR1a at ERK-preferred motifs, including S/TP (a), TP (b), and PXSP (c). Cerebellar mGluR1a was immunopurified by the anti-mGluR1a antibody. Phosphorylation signals at three phosphomotifs (pS/TP, pTP, and PXpSP) in immunopurified mGluR1a were detected by immunoblots (IB) with indicated antibodies. d Dephosphorylation of mGluR1a PXSP phosphorylation by λ-protein phosphatase (λ-PP). Cerebellar slices were incubated with λ-PP (200–400 units) for 1 h at 30 °C. Note that PXSP phosphorylation was dephosphorylated by λ-PP. e Representative immunoblots illustrating effects of U0126 on phosphorylation of mGluR1a at PXSP and TP motifs and on pERK1/2-mGluR1a and ERK1/2-mGluR1a interactions in cerebellar neurons. f, g Quantifications of effects of U0126 on mGluR1a PXSP (f) and TP (g) phosphorylation. h Quantifications of effects of U0126 on pERK2-mGluR1a and ERK2-mGluR1a interactions. Cerebellar slices were incubated with U0126 (0.5 or 5 µM) for 30 min at 30 °C (e–h). Slices were collected for mGluR1a immunoprecipitation (IP). Phosphorylation levels of mGluR1a at PXSP and TP and proteins bound to immunopurified mGluR1a (pERK1/2 and ERK1/2) were visualized by immunoblots. Values in graphs were measured as ratios of PXpSP to mGluR1a (f), pTP to mGluR1a (g), pERK2 to mGluR1a (h), and ERK2 to mGluR1a (h). All values were analyzed by one-way ANOVA: PXpSP (f), F(2, 7) = 5.05, p < 0.05; pTP (g), F(2, 7) = 0.26, p > 0.05; pERK2 (h), F(2, 7) = 37.44, p < 0.05; and ERK2 (h), F(2, 7) = 14.67, p < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3–4 per group). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle

ERK Supports Surface Expression of mGluR1a

To determine the role of ERK in regulating mGluR1a, we first investigated whether ERK regulates surface expression of mGluR1a in cerebellar neurons. We utilized a surface receptor crosslinking assay to monitor changes in the surface versus intracellular expression of mGluR1a. BS3, a membrane-impermeable reagent, selectively crosslinks surface membrane-bound receptors to form BS3-linked high molecular weight aggregates as opposed to BS3-unlinked intracellular receptors with a normal molecular weight. BS3-linked surface receptors are readily separated from BS3-unlinked intracellular receptors on gel electrophoresis due to their different molecular weights. Indeed, BS3 treatment induced a high molecular band of mGluR1a, establishing BS3-linked surface receptor aggregates (Fig. 6a). Meanwhile, BS3-unlinked bands were seen as intracellular receptors. Quantification analysis of the amount of intracellular mGluR1a in BS3-treated tissue compared to control tissue reveals that less than half of mGluR1a was normally expressed in the intracellular fraction (Fig. 6b). No mGluR5 signals were shown in either control or BS3-treated cerebellar tissue (Fig. 6c). There was no effect of BS3 in crosslinking α-actinin, an intracellular protein (Fig. 6d), confirming the selectivity of BS3 in crosslinking surface proteins.

Fig. 6.

ERK-mediated surface expression of mGluR1a in rat cerebellar neurons. a A representative mGluR1a immunoblot from rat viable cerebellar slices treated with BS3 or vehicle control (Con). b Quantification of intracellular mGluR1a dimers in BS3-treated and control slices. c, d A representative immunoblot of mGluR5 (c) or α-actinin (d) from rat viable cerebellar slices treated with BS3 or vehicle control. e Effects of U0126 on surface and intracellular expression of mGluR1a. Note that U0126 significantly reduced surface expression of mGluR1a. f Effects of U0126 on the surface-to-intracellular ratio (S:I ratio) of mGluR1a expression. g Effects of U0126 on α-actinin expression. Representative immunoblots are shown to the left of the quantified data (e, g). Cerebellar slices were incubated with vehicle (Veh) or U0126 (5 µM) for 30 min at 30 °C (e–g). After drugs were washed off, slices were used for BS3 crosslinking assays. All values were analyzed by Student’s t test: BS3-unlinked dimers (b), t = 4.45, p < 0.05; surface mGluR1a (e), t = 2.48, p < 0.05; intracellular mGluR1a (e), t = 2.19, p > 0.05; S:I ratio (f), t = 4.09, p < 0.05; and α-actinin (g), t = 0.68, p > 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–6 per group). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle

We then tested the effect of ERK inhibition on surface expression of mGluR1a. Pretreatment of cerebellar slices with U0126 (5 µM, 30 min) reduced the abundance of mGluR1a in surface fractions (Fig. 6e). mGluR1a in intracellular fractions was elevated, although it did not reach a statistically significant level. The surface-to-intracellular ratio of mGluR1a expression was substantially reduced due to concurrent and opposite changes in surface and intracellular pools (Fig. 6f). No change was observed in the level of an intracellular protein α-actinin (Fig. 6g). These data indicate that ERK plays a positive role in stabilizing surface expression of mGluR1a in cerebellar neurons.

ERK Regulates the mGluR1-IP3 Signaling Pathway

mGluR1 stimulates PLCβ1 via Gαq proteins, which in turn hydrolyzes phosphoinositide to produce IP3 molecules [1, 2]. In this study, we measured the mGluR1-stimulated IP3 yield as a functional output to evaluate the role of ERK in regulating mGluR1 signaling. Adding an mGluR1/5 agonist DHPG (100 µM) to rat cerebellar slices induced a typical increase in cytosolic IP3 levels (Fig. 7a). Pretreatment with an mGluR1 selective antagonist 3-MATIDA (10 µM, 30 min prior to DHPG) completely blocked the IP3 formation induced by DHPG (Fig. 7b), verifying that IP3 responses to DHPG were mediated by mGluR1. Remarkably, inhibition of ERK by U0126 at 5 µM significantly reduced IP3 responses to DHPG, while the inhibitor at 0.5 µM did not (Fig. 7c). U0126 at either concentration did not alter the basal level of IP3. Thus, under normal conditions, ERK is critical for mGluR1 to trigger its IP3 pathway.

Fig. 7.

ERK regulates the mGluR1-mediated IP3 production in rat cerebellar neurons. a A rapid elevation of cytosolic IP3 levels following application of DHPG (100 µM). b Effects of the mGluR1 antagonist 3-MATIDA on the DHPG-stimulated IP3 formation. Note that 3-MATIDA completely blocked IP3 responses to DHPG. c Effects of U0126 on the DHPG-stimulated IP3 production. Note that U0126 at 5 µM significantly reduced IP3 responses to DHPG. d Tat-fusion mGluR1a interaction-dead (Tat-mGluR1a-id) and sequence-scrambled control (Tat-mGluR1a-con) peptides. The underlined letters (LNIFRRKK) represent core hydrophobic and basic residues in a D domain-like sequence of mGluR1a-CT. e, f Effects of Tat-fusion peptides on the ERK2-mGluR1a association (e) and DHPG-stimulated IP3 production (f). Note that Tat-mGluR1a-id but not Tat-mGluR1a-con peptides reduced the ERK2-mGluR1a association and IP3 responses to DHPG. Experiments were carried out in rat cerebellar slices. 3-MATIDA (10 µM) or U0126 (0.5 or 5 µM) was applied 30 min before and during 20–25 s incubation of DHPG (100 µM) (b, c). Tat-fusion peptides (5 µM in e and 2 or 5 µM in f) were added to cerebellar slices for 30 min. Slices were then used for coimmunoprecipitation detection of the ERK2-mGluR1a association (e) or IP3 measurements (f). Values in the panel a were analyzed by Student’s t test (t = 3.21, p < 0.05). Values in panels b, c, e, and f were analyzed by one-way ANOVA: 3-MATIDA + DHPG (b), F(3, 16) = 35.05, p < 0.05; U0126 + DHPG (c), F(5, 26) = 19.10, p < 0.05; ERK2-mGluR1a interactions (e), F(2, 15) = 7.50, p < 0.05; and Tat-peptides + DHPG (f), F(9, 29) = 9.55, p < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–7 per group). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle (a, e) or vehicle + vehicle (b, c, and f). +p < 0.05 versus vehicle + DHPG (b, c, and f)

We next used a different approach to evaluate the role of ERK in mGluR1-IP3 signaling. The ERK binding motif in substrates has a significant role in determining the specificity and efficiency of ERK [38]. The D domain is a major ERK-binding motif identified in ERK substrates. A typical D domain is generally comprised of a stretch of hydrophobic amino acids (Φ-X-Φ where Φ is a hydrophobic residue such as L, I, and V and X is any amino acid) and a nearby cluster of positively charged, basic residues [38–40]. Noticeably, a D domain-like sequence (LNIFRRKK) exists in mGluR1a-CT1a(K841-N885), a region we identified for the ERK2 binding (Fig. 3c – e). To determine the importance of this D domain-containing region to the ERK2 binding to mGluR1a, we synthesized a peptide (SNTFLNIFRRKKP) that flanks the D domain and then tested the effect of the peptide on the ERK2-mGluR1a binding. The peptide blocked the binding of ERK2 to mGluR1a-CT1a in in vitro binding assays, while a sequence-scrambled control peptide (LFRSNTNFRIKPK) did not (data not shown). Thus, as expected, the D domain is critical for the ERK2 binding to mGluR1a. We next utilized these peptides to evaluate the importance of the ERK2-mGluR1a interaction for regulating mGluR1-IP3 signaling. We performed this experiment in rat cerebellar slices. To assure efficient transduction of peptides into neurons, we fused a Tat domain (YGRKKRRQRRR) known to render fused materials’ cell permeability [41] to the peptide (Fig. 7d). Adding Tat-fusion mGluR1a interaction dead (TatmGluR1a-id) peptides (5 µM) to cerebellar slices significantly reduced the interaction of ERK2 with mGluR1a as detected by coimmunoprecipitation with an anti-mGluR1a antibody (Fig. 7e). Similarly, Tat-mGluR1a-id (5 although not 2 µM) reduced IP3 responses to DHPG (Fig. 7f). In contrast, Tat-fusion mGluR1a control (TatmGluR1a-con) peptides showed an insignificant effect on the ERK2-mGluR1a interaction and IP3 responses (Fig. 7e, f). Thus, the ERK2-mGluR1a interaction is essential for mGluR1 to activate the IP3 cascade.

ERK Regulates the mGluR1-Src Signaling Pathway

Activation of mGluR1 stimulates another signaling pathway involving a Src family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases [42]. Src, like mGluR1, is enriched at synaptic sites [43]. Activation of mGluR1/5 potentiated NMDA receptors via a Src-dependent mechanism [44–46]. DHPG and the mGluR5 agonist CHPG increased autophosphorylation of Src at conserved Y416 in the activation loop in cultured cortical and hippocampal neurons [47, 48], which is deemed to enable activation of the kinase [49, 50]. Thus, Src phosphorylation serves as an integrative measure of mGluR1 activity. In this study, we investigated the role of ERK in regulating mGluR1 signaling to Src in cerebellar slices. Applying DHPG (100 µM, 15 min) induced a marked increase in Src Y416 phosphorylation, while total cellular Src proteins remained unchanged (Fig. 8a). Pretreatment with 3-MATIDA (10 µM, 30 min prior to DHPG) blocked the DHPG-stimulated Y416 phosphorylation (Fig. 8b), confirming that it was an mGluR1-mediated event. Inhibition of ERK with U0126 had no significant effect on basal Y416 phosphorylation (Fig. 8c). However, U0126 at 5 µM (30 min prior to DHPG) substantially reduced responses of Y416 phosphorylation to DHPG, while U0126 at 0.5 µM did not (Fig. 8d). These data indicate that active ERK is critical for maintaining efficacy of mGluR1 signaling in triggering the Src pathway.

Fig. 8.

Effects of inhibition of ERK by U0126 on the DHPG-stimulated Src Y416 phosphorylation in rat cerebellar neurons. a Effects of DHPG (100 µM, 15 min) on Src Y416 phosphorylation. b Effects of the mGluR1 antagonist 3-MATIDA on the DHPG-stimulated Y416 phosphorylation. Note that 3-MATIDA completely blocked the Y416 phosphorylation induced by DHPG. c Effects of U0126 (0.5 and 5 µM, 30 min) on basal Y416 phosphorylation. d Effects of U0126 on the DHPG-stimulated Y416 phosphorylation. Note that U0126 at 5 µM substantially blocked the Y416 phosphorylation induced by DHPG. 3-MATIDA (10 µM) or U0126 (0.5 or 5 µM) was applied 30 min before and during vehicle (Veh) or DHPG incubation (100 µM, 15 min) (b, d). Experiments were carried out on rat cerebellar slices. Values in the panel a were analyzed by Student’s t test (t = 3.08, p < 0.05). Values in panels b–d were analyzed by one-way ANOVA: 3-MATIDA (b), F(3, 16) = 10.02, p < 0.05; U0126 (c), F(2, 9) = 0.46, p > 0.05; and U0126 + DHPG (d), F(3, 16) = 11.22, p < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–5 per group). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle (a) or vehicle + vehicle (b, d). +p < 0.05 versus vehicle + DHPG (b, d)

Discussion

We conducted this study to explore the relationship between ERK and mGluR1a. We found that recombinant ERK2 bound to mGluR1a CT in vitro. Through this binding, ERK2 phosphorylates multiple serine residues in the distal segment of mGluR1a CT. In rat cerebellar neurons, native ERK2 was enriched at synaptic sites. Synaptic ERK2 formed complexes with mGluR1a. The mGluR1a-associated ERK2 was catalytically active and constitutively phosphorylated mGluR1a. Such constitutively active phosphorylation was required for facilitating surface trafficking of mGluR1a and for tuning up the responsivity of the receptor to agonist stimulation. Our results demonstrate that ERK2 interacts with neighboring mGluR1a and phosphorylation-dependently regulates subcellular distribution and signaling efficacy of mGluR1.

Given its size, mGluR1a CT is thought to be a preferred domain hosting protein–protein interactions. This is indeed the case for most mGluR1a-interacting partners discovered so far [6, 7]. Like these partners, ERK2 bound to mGluR1a CT. The actual binding area is notably located in the membrane proximal CT1 region different from the phosphorylation sites identified in the distal CT2. This difference is consistent with the classical model in which ERK binds and phosphorylates separate sites in most, if not all, substrates [31]. Since the direct interaction was essential for ERK2 to phosphorylate Elk-1 and feedback-phosphorylate MEK [51, 52], the ERK2-mGluR1a interaction is considered to be an important step leading to phosphorylation.

ERK2 phosphorylation of mGluR1a seems to be variant specific. Given that the short-form mGluR1 variants (1b, 1c, and 1d) have only 57–72 amino acids in their truncated CT tails [53] and lack the distal mGluR1a CT segment, the identified ERK phosphorylation sites in the distal mGluR1a CT are restricted to mGluR1a. In addition, a significant level of basal phosphorylation exists in mGluR1a in cerebellar neurons. This constitutively active phosphorylation has been demonstrated to play a critical role in regulating surface expression and signaling efficacy of mGluR1a under steady-state conditions (see below).

ERK is now known to reside in neuronal peripheral structures such as synapses, in addition to its early viewed nuclear location. This was consistently seen in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, striatum [13–16], and now cerebellum (this study). At synaptic sites, ERK showed an isoform gradient with a higher ERK2 than ERK1 level [16, this study]. Within the PSD, only ERK2 coexisted with MAPK cascade components [17, 18]. In response to stimulation, pERK was visualized in hippocampal and visual cortical synapses [14, 15]. Dopamine stimulation also increased synaptic rather than extrasynaptic ERK2 phosphorylation in the striatum and prefrontal cortex [16]. Thus, ERK, primarily the ERK2 isoform, can function at synaptic sites to regulate local substrates. A number of synaptic substrates were suggested by mass spectrometric analysis [29]. Individual substrates identified include PKCα [54], Kv4.2 potassium channels [55, 56], synapsin I [57], δ-catenin [29], PSD-93 [25], and PSD-95 [58]. However, at present, the number of substrates identified in the synapse is still far less than those identified in the nucleus [59, 60]. Our study adds a new ERK2-interacting substrate at synaptic sites and suggests a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism linking ERK2 to mGluR1a.

Phosphorylation has functional consequences in regulating mGluR1 [8, 61, 62]. Early studies identified PKC with this capacity [63–66]. By phosphorylating an IL2 threonine residue (T695) [67], PKC feedback-desensitized mGluR1a in HEK293 cells [68]. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is another kinase linking to mGluR1a. By phosphorylating T871, a CT site adjacent to the G protein coupling domain of mGluR1a [61], CaMKII formed a feedback loop facilitating agonist-induced desensitization of mGluR1a in striatal neurons [22]. In addition to PKC and CaMKII, proline-directed kinases, cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) and ERK, phosphorylated a serine site within the Homer-binding domain (−PPSPF-) conserved in mGluR1a (S1154) and mGluR5 (S1126) in adult rat brains as detected by a phospho- and site-specific antibody [30, 69]. This phosphorylation was reduced by CDK5 siRNAs [30], a CDK5 inhibitor (purvalanol A), or U0126 in rat cultured cortical neurons [69]. The phosphorylation of mGluR1/5 at the Homer-binding site increased Homer binding [30, 69] and inhibited group I mGluR coupling to voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels in superior cervical ganglion neurons [69]. In this study, we focused on ERK2 and mGluR1a in the cerebellum and carried out an in-depth study. Our results support a synaptic ERK2-mGluR1a interplay model in cerebellar neurons. In details, a sub-pool of ERK2 in the synaptic compartment interacts with local mGluR1a. ERK2 phosphorylates a set of serine residues in the distal mGluR1a CT region. This leads to steady-state surface expression of the receptor and enables a full scale of mGluR1a signaling in triggering both the IP3 and Src pathways. Recently, the D1 receptor agonist or brain-derived neurotrophic factor activated ERK1/2 and induced U0126-sensitive mGluR5-S1126, although not mGluR5-T1123, phosphorylation in striatal neurons, which facilitated Pin1-mGluR5 interactions and thereby potentiated mGluR5 activity in triggering NMDA receptor-mediated currents [70]. Apparently, the regulation of mGluR1/5 could be signaling output specific. The fact that multiple kinases are involved in the mGluR1a regulation supports a notion that different kinases work in concert to orchestrate normal receptor activity and construct accurate receptor responses to ligand stimulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Minglei Guo and Bing Xue for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants DA10355 (J.Q.W.) and MH61469 (J.Q.W.), the NRF grants 2013R1A2A2A04016044 (E.S.C.) and 2015R1A5A7037508 (E.S.C.), and the MFDS 14182MFDS977 (E.S.C.), South Korea.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Competing Interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Niswender CM, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:295–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, Menniti ES, Vance KM, Ogden KK, Hansen KB, Yuan H, et al. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:405–496. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicoletti F, Bockaert J, Collingridge GL, Conn PJ, Ferraguti F, Schoepp DD, Wroblewski JT, Pin JP. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: from the workbench to the bedside. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:1017–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lujan R, Nusser Z, Roberts JD, Shigemoto R, Somogyi P. Perisynaptic location of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1 and mGluR5 on dendrites and dendritic spines in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1488–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuwajima M, Hall RA, Aiba A, Smith Y. Subcellular and subsynaptic localization of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in the monkey subthalamic nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:589–602. doi: 10.1002/cne.20158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enz R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors and interacting proteins: evolving drug targets. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:145–156. doi: 10.2174/138945012798868452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagni L. Diversity of metabotropic glutamate receptor-interacting proteins and pathophysiological functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;970:63–79. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0932-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim CH, Lee J, Lee JY, Roche KW. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: phosphorylation and receptor signaling. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao LM, Guo ML, Jin DZ, Fibuch EE, Choe ES, Wang JQ. Posttranslational modification biology of glutamate receptors and drug addiction. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:19. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweatt JD. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signaling and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JQ, Fibuch EE, Mao LM. Regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by glutamate receptors. J Neurochem. 2007;100:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz J, Harris HW, Guitart X, Terwilliger RZ, Haycock JW, Nestler EJ. Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERKs) and ERK kinase (MEK) in brain: regional distribution and regulation by chronic morphine. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1285–1297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01285.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boggio EM, Putignano E, Sassoe-Pognetto M, Pizzorusso T, Glustetto M. Visual stimulation activates ERK in synaptic and somatic compartments of rat cortical neurons with parallel kinetics. PLoS One. 2007;2:e604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sindreu CB, Scheiner ZS, Storm DR. Ca2+-stimulated adenylyl cyclases regulate ERK-dependent activation of MSK1 during fear conditioning. Neuron. 2007;53:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao LM, Reusch JM, Fibuch EE, Liu Z, Wang JQ. Amphetamine increases phosphorylation of MAPK/ERK at synaptic sites in the rat striatum and medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2013;1494:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki T, Okumura-Noji K, Nishida E. ERK2-type mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and its substrates in postsynaptic density fractions from the rat brain. Neurosci Res. 1995;22:277–285. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00902-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki T, Mitake S, Murata S. Presence of up-stream and downstream components of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in the PSD of the rat forebrain. Brain Res. 1999;840:36–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01762-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao LM, Wang JQ. Synaptically localized mitogen-activated protein kinases: local substrates and regulation. Mol Neurobiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9535-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu XY, Mao LM, Zhang GC, Papasian CJ, Fibuch EE, Lan HX, Zhou HF, Xu M, et al. Activity-dependent modulation of limbic dopamine D3 receptors by CaMKII. Neuron. 2009;61:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo ML, Fibuch EE, Liu XY, Choe ES, Buch S, Mao LM, Wang JQ. CaMKIIα interacts with M4 muscarinic receptors to control receptor and psychomotor function. EMBO J. 2010;29:2070–2081. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin DZ, Guo ML, Xue B, Fibuch EE, Choe ES, Mao LM, Wang JQ. Phosphorylation and feedback regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3402–3412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3192-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gille H, Kortenjann M, Thomae O, Moomaw C, Slaughter C, Cobb MH, Shaw PE. ERK phosphorylation potentiates Elk-1-mediated ternary complex formation and transactivation. EMBO J. 1995;14:951–962. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruzalegui FH, Cano E, Treisman R. ERK activation induces phosphorylation of Elk-1 at multiple S/T-P motifs to high stoichiometry. Oncogene. 1999;18:7948–7957. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo ML, Xue B, Jin DZ, Mao LM, Wang JQ. Interactions and phosphorylation of postsynaptic density 93 (PSD-93) by extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) Brain Res. 2012;1460:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao LM, Wang W, Chu XP, Zhang GC, Liu XY, Yang YJ, Haines M, Papasian CJ, et al. Stability of surface NMDA receptors controls synaptic and behavioral adaptations to amphetamine. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:602–610. doi: 10.1038/nn.2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabatadze N, Huang G, May RM, Jain A, Woolley CS. Sex differences in molecular signaling at inhibitory synapses in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2015;35:11252–11265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1067-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cansev M, Orhan F, Yaylagul EQ, Isik E, Turkyilmaz M, Aydin S, Gumus A, Sevinc C, et al. Evidence for the existence of pyrimidinergic transmission in rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2015;91:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edbauer D, Cheng D, Batterton MN, Wang CF, Duong DM, Yaffe MB, Peng J, Shang M. Identification and characterization of neuronal mitogen-activated protein kinase substrates using a specific phosphomotif antibody. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:681–695. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800233-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orlando LR, Ayala R, Kett LR, Curley AA, Duffner J, Bragg DC, Tsai LH, Dunah AW, et al. Phosphorylation of the homer-binding domain of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors by cyclin-dependent kinase 5. J Neurochem. 2009;110:557–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Songyang Z, Lu KP, Kwon YT, Tsai LH, Filhol O, Cochet C, Brickey DA, Soderling TR, et al. A structure basis for substrate specificities of protein Ser/Thr kinases: primary sequence preference of casein kinases I and II, NIMA, phosphorylase kinase, calmodulin-dependent kinase II, CDK5, and Erk1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6486–6493. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin LJ, Blackstone CD, Huganir RL, Price DL. Cellular localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in rat brain. Neuron. 1992;9:259–270. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90165-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shigemoto R, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Sugihara H, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR5, in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1993;163:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90227-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fotuhi M, Sharp AH, Glatt CE, Hwang PM, von Krosigk M, Snyder SH, Dawson TM. Differential localization of phosphoinositide-linked metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1) and the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2001–2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-02001.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romano C, Miller JK, Hyrc K, Dikranjan S, Mennerick S, Takeuchi Y, Goldberg MP, O’Malley KL. Covalent and noncovalent interactions mediate metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 dimerization. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaffer C, Guo ML, Fibuch EE, Mao LM, Wang JQ. Regulation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor expression in the rat striatum and prefrontal cortex in response to amphetamine in vivo. Brain Res. 2010;1326:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casar B, Arozarena I, Sanz-Moreno V, Pinto A, Agudo-Ibanez L, Marais R, Lewis RE, Berciano MT, et al. Ras subcellular localization defines extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 substrate specificity through distinct utilization of scaffold proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1338–1353. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01359-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ubersax JA, Jr, Ferrell JE. Mechanisms of specificity in protein phosphorylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:530–541. doi: 10.1038/nrm2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharrocks AD, Yang SH, Galanis A. Docking domains and substrate-specificity determinations for MAP kinases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:448–453. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanoue T, Adachi M, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. A conserved docking motif in MAP kinases common to substrates, activators and regulators. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:110–116. doi: 10.1038/35000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aarts M, Liu Y, Liu L, Besshoh S, Arundine M, Gurd JW, Wang YT, Salter MW, et al. Treatment of ischemic brain damage by perturbing NMDA receptor-PSD-95 protein interactions. Science. 2002;298:846–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1072873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heuss C, Scanziani M, Gahwiler BH, Gerber U. G-protein-independent signaling mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1070–1077. doi: 10.1038/15996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalia LV, Gingrich JR, Salter MW. Src in synaptic transmission and plasticity. Oncogene. 2004;23:8007–8016. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benquet P, Gee CE, Gerber U. Two distinct signaling pathways upregulate NMDA receptor responses via two distinct metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9679–9686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09679.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo W, Wei F, Zou S, Robbins MT, Sugiyo S, Ikeda T, Tu JC, Worley PF, et al. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptor NMDA receptor coupling and signaling cascade mediate spinal dorsal horn NMDA receptor 2B tyrosine phosphorylation associated with inflammatory hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9161–9173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3422-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarantis K, Tsiamaki E, Kouvaros S, Papatheodoropoulos C, Angenatou F. Adenosine A2A receptors permit mGluR5-evoked tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2B (Tyr1472) in rat hippocampus: a possible key mechanism in NMDA receptor modulation. J Neurochem. 2015;135:714–726. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heidinger V, Manzerra P, Wang XQ, Strasser U, Yu SP, Choi DW, Behrens MM. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 1-induced upregulation of NMDA receptor current: mediation through the Pyk2/Src-family kinase pathway in cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5452–5461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05452.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takagi N, Besshoh S, Marunouchi T, Takeo S, Tanonaka K. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 activation enhances tyrosine phosphorylation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and NMDA-induced cell death in hippocampal cultured neurons. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:2224–2229. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roskoski R., Jr Src kinase regulation by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okada M. Regulation of the Src family kinase by Csk. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1385–1397. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang SH, Yates PR, Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ, Sharrocks AD. The Elk-1 ETS-domain transcription factor contains a mitogen-activated protein kinase targeting motif. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:710–720. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu B, Wilsbacher JL, Collisson T, Cobb MH. The N-terminal ERK-binding site of MEK1 is required for efficient feedback phosphorylation by ERK2 in vitro and ERK activation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34029–34035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pin JP, Waeber C, Prezeau L, Bockaert J, Heinemann SF. Alternative splicing generates metabotropic glutamate receptor inducing different patterns of calcium release in Xenopus oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10331–10335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Debata PR, Ranasinghe B, Berliner A, Curcio GM, Tantry SJ, Ponimaskin E, Banerjee P. Erk1/2-dependent phosphorylation of PKCalpha at threonine 638 in hippocampal 5-HT(1A) receptor-mediated signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adams JP, Anderson AE, Varga AW, Dineley KT, Cook RG, Pfaffinger PJ, Sweatt JD. The A-type potassium channel Kv4.2 is a substrate for the mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2277–2287. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schrader LA, Bimbaum SG, Nadin BM, Ren Y, Bui D, Anderson AE, Sweatt JD. ERK/MAPK regulates the Kv4.2 potassium channel by direct phosphorylation of the pore-forming subunit. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C852–C861. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00358.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jovanovic JN, Benfenati F, Siow YL, Sihra TS, Sanghera JS, Pelech SL, Greengard P, Czernik AJ. Neurotrophins stimulate phosphorylation of synapsin I by MAP kinase and regulate synapsin I-actin interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3679–3683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabio G, Reuver S, Feijoo C, Hasegawa M, Thomas GM, Centeno F, Kuhlendahl F, Leal-Ortiz S, et al. Stress- and mitogen-induced phosphorylation of the synapse-associated protein SAP90/PSD-95 by activation of SAPK3/p38gamma and ERK1/ERK2. Biochem J. 380:19–30. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Treisman R. Regulation of transcription by MAP kinase cascades. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kosako H, Yamaguchi N, Aranami C, Ushiyama M, Kose S, Imamoto N, Taniguchi H, Nishida E, et al. Phosphoproteomics reveals new ERK MAP kinase targets and links ERK to nucleoporin-mediated nuclear transport. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1026–1035. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dhami GK, Ferguson SS. Regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, desensitization and endocytosis. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mao LM, Liu XY, Zhang GC, Chu XP, Fibuch EE, Wang LS, Liu Z, Wang JQ. Phosphorylation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1/5) in vitro and in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manzoni OJ, Finiels-Marlier F, Sassetti L, Blockaert J, le Peuch C, Sladeczek FA. The glutamate receptor of the Qp-type activates protein kinase C and is regulated by protein kinase C. Neurosci Lett. 1990;109:146–151. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90553-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Catania MV, Aronica E, Sortino MA, Canonico PL, Nicoletti F. Desensitization of metabotropic glutamate receptors in neuronal cultures. J Neurochem. 1991;56:1329–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb11429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomsen C, Mulvihill ER, Haldeman D, Pickering DS, Hampson DR, Suzdak PD. A pharmacological characterization of the mGluR1α subtype of the metabotropic glutamate receptor expressed in a cloned baby hamster kidney cell line. Brain Res. 1993;619:22–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91592-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alaluf S, Mulvihill ER, McIlhinney RA. Rapid agonist mediated phosphorylation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1-alpha by protein kinase C in permanently transfected BHK cells. FEBS Letter. 1995;367:301–305. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00575-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Medler KF, Bruch RC. Protein kinase Cβ and δ selectively phosphorylate odorant and metabotropic glutamate receptors. Chem Senses. 1999;24:295–299. doi: 10.1093/chemse/24.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Francesconi A, Duvoisin RM. Opposing effects of protein kinase C and protein kinase a on metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling: selective desensitization of the inositol triphosphate/Ca2+ pathway by phosphorylation of the receptor-G protein-coupling domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6185–6190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu JH, Yang L, Kammermeier PJ, Moore CG, Brakeman PR, Tu J, Yu S, Petralia RS, et al. Preso1 dynamically regulates group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:836–844. doi: 10.1038/nn.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park JM, Hu JH, Milshteyn A, Zhang PW, Moore CG, Park S, Datko MC, Domingo RD, et al. A prolyl-isomerase mediates dopamine-dependent plasticity and cocaine motor sensitization. Cell. 2013;154:637–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]