Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) sometimes occur following Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) administration for allogenic stem cell transplantation but are rare in aplastic anemia (AA) patients. A 55-year-old woman with AA following ATG developed refractory fever and was diagnosed with EBV-LPD. She was successfully treated with weekly rituximab monotherapy; however, she developed EBV encephalitis. She was admitted to the intensive care unit and finally recovered from unconsciousness. EBV-LPD should be considered after ATG for AA when symptoms appear. Because EBV-LPD following ATG for AA can rapidly progress, weekly monitoring of EBV-DNA and early intervention may be necessary.

Keywords: Anti-thymocyte globulin, Epstein-Barr virus, aplastic anemia, encephalitis, rituximab, lymphoproliferative disorder

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a gammaherpesvirus that latently infects approximately 90% of human adults. The main targets of EBV infection are naïve B-cells, which are activated to proliferating blasts. Infection by EBV and the spread of EBV are controlled by host antibodies and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). However, the host immune system cannot completely eliminate EBV; therefore, infected B cells can persist at low levels (1).

Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) is a rabbit-derived polyclonal antibody with a high affinity for T cells and leukocyte surface antigens. ATG reduces the levels of antigen-reactive T cells in the peripheral blood. Impairment of the CTL response is associated with abnormal proliferation of B cells. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLDs) are lymphoid or plasmatic proliferation disorders that develop after solid organ transplantation or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) because of immunosuppression (2). ATG-containing conditioning regimens have been reported to increase the risk of PTLDs (3-5). The recommended strategy for the prevention of PTLDs is the reduction of immunosuppression with or without preemptive rituximab therapy, based on regular monitoring of EBV deoxyribonucleic acid (EBV-DNA) loads in peripheral blood. Preemptive rituximab therapy has been reported to prevent the development of PTLDs in approximately 90% of cases (6).

The initial treatment of newly diagnosed acquired severe aplastic anemia is allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) from a human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-identical sibling donor, if available, for patients <40 year of age (7,8). Immunosuppressive therapy is recommended for patients ≥40 years of age or with no HLA-identical sibling donor (9). In the setting of allo-HSCT, ATG is associated with an increased risk of EBV reactivation and PTLD (10). Scheinberg et al. reported that EBV reactivation occurred in 100% of EBV-seropositive patients after receiving rabbit ATG at a dose of 3.5 mg/kg with cyclosporin A (CsA) therapy for severe aplastic anemia (11).

The risk factors for EBV-LPD following treatment for aplastic anemia have not yet been determined. With regard to PTLD following allo-SCT, the risk factors include a T cell depletion treatment regimen, patient age >50 years, second allo-HCT, the presence of graft-versus-host disease, the use of cord blood, and haploidentical transplant (6). In patients with aplastic anemia, the reactivation of EBV following treatment using rabbit ATG was reportedly more severe than that following treatment using horse ATG or alemtuzumab (11,12).

Ten cases of EBV reactivation and/or LPDs following immunosuppressive therapy for aplastic anemia have been reported in the literature. However, to our knowledge, the outcome of EBV encephalitis following ATG therapy has not been reported (13-22). EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (EBV-LPDs) following ATG therapy for aplastic anemia are rapidly progressive and often fatal. Reduction of immunosuppression and rituximab monotherapy with or without combination chemotherapy have been reported as treatment options for EBV-LPDs and PTLDs. We herein report a case of a patient with aplastic anemia who developed EBV-LPD and EBV encephalitis following ATG therapy who was successfully treated using rituximab monotherapy.

Case Report

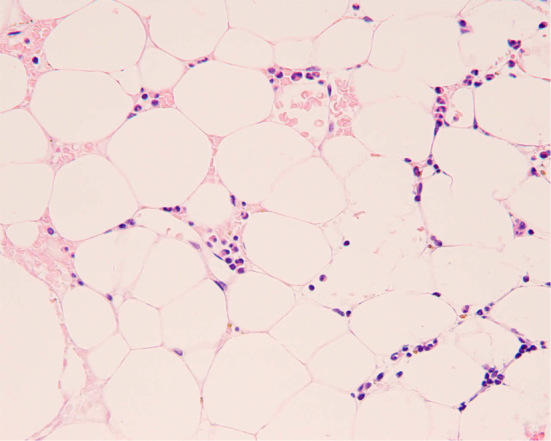

A 55-year-old woman was referred to our hospital because of pancytopenia. Her medical history included lumpectomy and adjuvant radiochemotherapy for breast cancer at 49 years of age. Because her peripheral blood count had gradually decreased, she was admitted to our department in May 2012. On a physical examination, the patient had conjunctival pallor and local purpura of her lower legs. Laboratory studies revealed pancytopenia with an absolute neutrophil count of 0.4×109/L, reticulocyte count of 47.8×109/L, and platelet count of 17×109/L. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy showed severely hypoplastic marrow with 90% of the normal tissue replaced by adipose tissue and no evidence of increased blast cells, dysplasia, or atypical cells (Fig. 1). A chromosome analysis showed no abnormalities in 20 metaphases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine revealed severely fatty marrow. Indium chloride bone marrow scintigraphy showed decreased uptake of indium chloride by the bone marrow, which was consistent with aplastic anemia. The patient was diagnosed with severe aplastic anemia. The proportion of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)-type granulocytes was 0.0387% (>0.003%) and PNH-type red blood cells was 0.067% (>0.005%), which is considered to be a predictor of response to ATG and CsA therapy (7). A serological analysis showed that she was seropositive for antibodies to cytomegalovirus and EBV; therefore, we initiated treatment using rabbit ATG and CsA.

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of the patient’s bone marrow smear at the time of diagnosis of aplastic anemia. Ninety percent of the normal bone marrow tissue was replaced by adipose tissue with no blasts or mature cells. There were no atypical or malignant cells present. Magnification×100. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining.

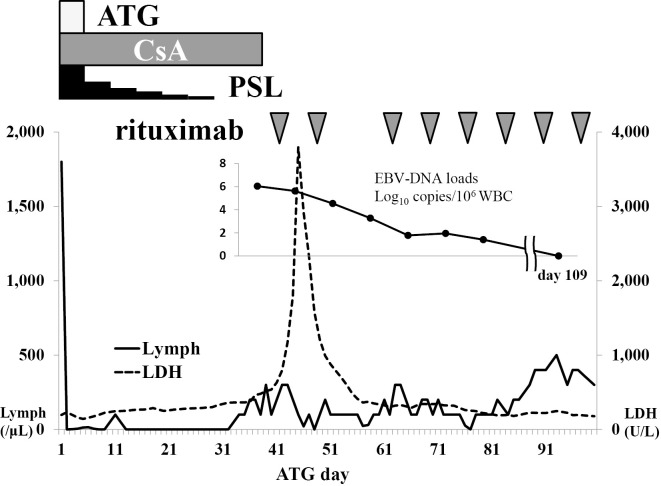

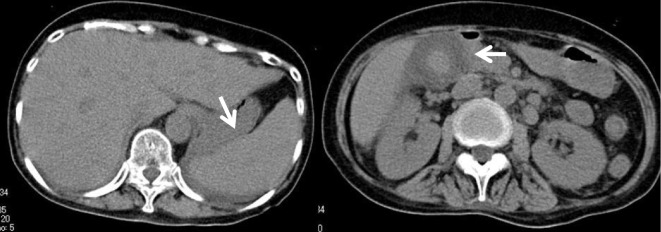

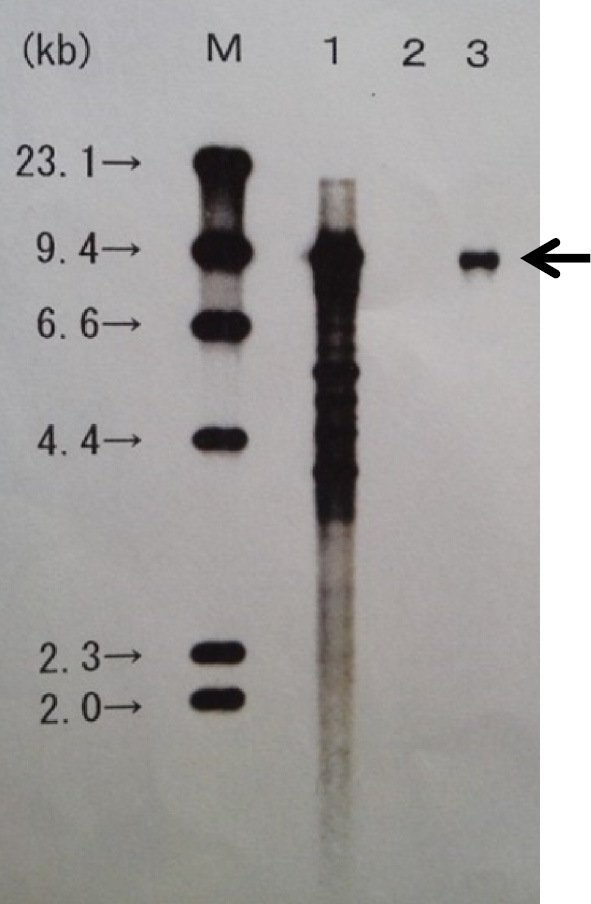

Her clinical course is shown in Fig. 2. ATG (3.75 mg/kg) was administered from Days 1 to 5, methylprednisolone (2 mg/kg) was administered, and CsA (6 mg/kg) on Day 6. On Day 28, she developed a high fever, which was unresponsive to antibiotics. CsA administration was discontinued on Day 39 because of liver injury and renal failure, indicated by elevated levels of total bilirubin (8.9 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (147 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (35 U/L), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (795 U/L), serum creatinine (2.58 mg/dL), and C-reactive protein (42.9 mg/dL). Ferritin had increased sharply to 66,320 ng/mL. Atypical lymphocytes were detected in her peripheral blood. On Day 41, a computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 3) revealed hepatosplenomegaly, thickening of the gallbladder wall because of acute hepatitis, and enlargement of multiple abdominal lymph nodes. Lymph node biopsy could not be performed because there were no superficial lymphadenopathies. In addition, the patient developed respiratory failure and was transferred to the intensive care unit and immediately intubated. The serum LDH level increased to >3,000 U/L, and the serum EBV-DNA level increased to 1.1×106 copies/106 cells. These clinical signs and laboratory data strongly suggested the development of EBV-LPD; therefore, we administered rituximab at 375 mg/m2 once per week. She was afebrile a few days after the first administration of rituximab. EBV-LPD was confirmed because of the monoclonality of EBV-DNA in her peripheral blood by Southern blotting hybridization (Fig. 4). Following a second cycle of rituximab, she recovered from respiratory failure and was extubated.

Figure 2.

Clinical course of the patient. Forty-five days after ATG initiation, the serum LDH level was elevated to more than 3,000 U/L, and the serum EBV-DNA level increased to 1.1×106 copies/106 cells. Following rituximab therapy, these levels rapidly decreased. Rituximab was administered once a week for 8 weeks.

Figure 3.

Abdominal computed tomography before the initiation of rituximab. Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated hepatosplenomegaly, increased thickness of the gallbladder wall, and multiple enlarged abdominal lymph nodes.

Figure 4.

Southern blot analysis demonstrated monoclonality of the EBV-infected cells. M’ represents the size marker of the DNA; No. 1 is the positive control, No. 2 is the negative control, and No. 3 is the patient’s peripheral blood sample.

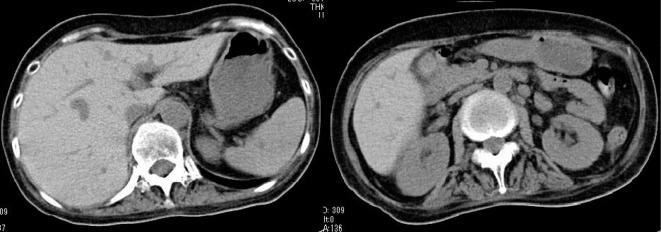

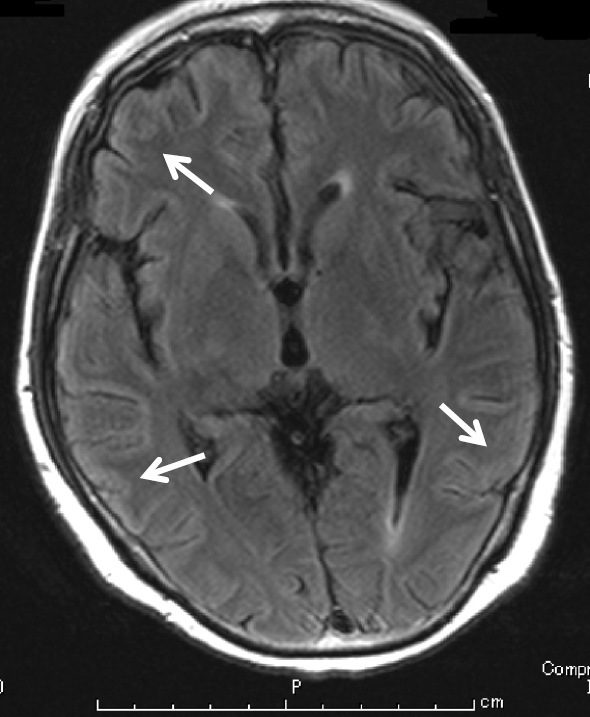

Although her general status and laboratory data had improved, she suddenly fell unconscious three days after the second cycle of rituximab. Cranial T2-weighted MRI and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (Fig. 5) showed high-intensity lesions in her cerebral cortex. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis for herpes simplex virus 1, 2 (HSV-1, 2), EBV, human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6), varicella zoster virus (VZV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) was performed using the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and EBV-DNA was detected in the CSF sample. After EBV encephalitis with LPD was diagnosed, we administered ganciclovir and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). As shown in Fig. 2, a real-time PCR analysis showed that the serum EBV-DNA level had rapidly decreased, and she regained consciousness. After eight subsequent courses of rituximab treatment, the EBV-DNA loads decreased below the detection limit, and the symptoms of EBV-LPDs and EBV encephalitis disappeared. A CT scan also revealed that there was no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, enlarged gallbladder, or abdominal lymphoadenopathy (Fig. 6). Twenty-two months following ATG initiation, she achieved a partial response for aplastic anemia according to the response criteria previously described by Camitta (8). To date, EBV-LPD recurrence has not been observed.

Figure 5.

Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) fluid attenuation inversion recovery imaging. Cranial MRI fluid attenuation inversion recovery imaging revealed high-intensity lesions in the cerebral cortex, in keeping with a diagnosis of viral (EBV) encephalitis.

Figure 6.

Abdominal computed tomography after the eight cycles of rituximab. A CT scan revealed that there was no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, enlarged gallbladder, or abdominal lymphoadenopathy after treatment with rituximab.

Discussion

This case report demonstrated that EBV-associated LPD with EBV encephalitis following ATG therapy for aplastic anemia can be successfully treated with rituximab. This finding may have implications for future patient treatment because it suggests that early detection of EBV-DNA and EBV reactivation may be beneficial for patients receiving ATG treatment for aplastic anemia.

Ten previously reported cases of EBV reactivation and/or LPD following immunosuppressive therapy for aplastic anemia from the literature can be compared with this case, although no case included EBV encephalitis (13-22). As shown in Table, six previously reported patients with LPD achieved a complete response (CR) with reduction of immunosuppression and/or combination chemotherapy (14,16-19,22). The initial signs of EBV-LPDs are a fever, general fatigue, loss of appetite, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, appearance of atypical lymphocytes in peripheral blood, and/or elevation of serum LDH (13-22). In our case, the cessation of immunosuppressive agents did not improve the symptoms of EBV-LPD; however, rituximab monotherapy resulted in a CR.

Table.

Previous Case Reports of Lymphoproliferative Disorders Following Immunosuppressive Treatment for Aplastic Anemia.

| Age/sex | Dose and a type of ATG treatment | Time to appearance of initial symptoms of EBV-LPD following ATG | Time to diagnosis | Diagnosis | Peak EBV-viral loads | Treatment for LPD | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36/M | 0.75 mg/kg/d 9 days | 9 days | EBV-LPDs | Died | [13] | |||

| 42/F | Rabbit, 12.5 mg/kg/d | 2 weeks | 2 weeks | DLBCL | 4 × 106 copies/mL | Rituximab, CPM | CR | [14] |

| 54/M | Rabbit, 3.75 mg/kg/d 5 days | 26 days | 26 days | EBV-LPDs | 3.3 × 106 copies/106 WBC | Died | [15] | |

| 38/M | 1st: Rabbit, 3.5 mg/kg/d for 5 days 2nd: Horse 3.5 mg/kg/d for 1 day | 19 days | 24 days | Infectious mononucleosis | 30,000/150,000 cells | Cessation of CsA, Rituximab | CR | [16] |

| 55/M | Horse | Less than a month | 7 days after the appearance of initial symptoms | Diffuse atypical/clonal plasma cell hyperplasia | 60,060 copies/mL | Rituximab | CR | [17] |

| 55/M | Rabbit, 3.75 mg/kg/d for 5 days | About 3 months | 84 days | Atypical lymphocytes proliferation | 140 copies/106 WBC | Cessation of CsA | CR | [18] |

| 46/F | Rabbit, 3.75 mg/kg/d for 5 days | 26 days | 33 days | EBV-LPDs | 7.9 × 106 copies/mL | Cessation of CsA | CR | [19] |

| 81/M | Rabbit, 3.3 mg/kg/d for 5 days | 31 days | 34 days | EBV-LPDs | 4 × 106 copies/mL | Cessation of CsA, rituximab | Died | [20] |

| 69/W | Rabbit | About 30 days | 54 days | EBV-LPDs | 3 × 105 copies/mL | Died | [21] | |

| 26/M | Rabbit, 3.75 mg/kg/d for 5 days | 2 months | EBV-LPDs | 120 copies/mL | Reduction of CsA, rituximab | CR | [22] | |

| 55/F | Rabbit, 3.75 mg/kg/d 5 days | 28 days | 36 days | EBV-LPDs | 1.1 × 106 copies/106 cells | Cessation of CsA, rituximab | CR | Our case |

F: female, M: male, mg/kg/d: mg/kg/day, ATG: antithymocyte globulin, EBV: Epstein - Barr virus, EBV-LPD: EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorder, IM: infectious mononucleosis, DLBCL: diffuse large B cell lymphoma, CsA: cyclosporin A, CPM: cyclophosphamide, CR: complete response

Time to diagnosis indicates the duration from Day 1 on recent immunosuppression therapy to the appearance of the first symptom of LPD.

Weekly monitoring of the peripheral EBV-DNA load is recommended for high-risk patients following allo-HSCT (23). The peak incidence of early PTLDs occurs 6-12 months following allo-HSCT (24). EBV-LPDs in patients with aplastic anemia may occur earlier than in patients with PTLDs. Therefore, it may be reasonable to begin monitoring within a week after ATG initiation.

With regard to allo-HSCT, patients with EBV reactivation and sufficient T cells improved only by reduction of immunosuppression (25). Among patients who developed PTLDs following allo-HSCT, the response rate for rituximab with the reduction of immunosuppression was 84%, whereas the rate was only 61% without a reduction of immunosuppression (26). Our patient did not improve following reduction of immunosuppression; therefore, an anticancer agent was administered. This indicates that the reduction of immunosuppression following the development of LPDs may be less effective for EBV-LPDs after ATG than for PTLDs, which may be partly because EBV-LPDs following ATG for aplastic anemia generally develop before T cell reconstitution.

Other EBV-associated diseases sometimes concurrently develop with PTLDs. Three major EBV end-organ diseases in recipients of allo-HSCT are pneumonitis, encephalitis/myelitis, and hepatitis (27). Reportedly, EBV-associated diseases are more refractory to rituximab than other agents (27). The MRI features of central nervous system (CNS)-involved PTLD that develop after solid-organ transplantation are multiple contrast-enhancing, intra-axial lesions associated with extensive peritumoral edema (28). CNS-involved PTLD masses are generally hypercellular, appearing hypo- to isointense on both plain T1- and T2-weighted MRI (29). Unlike CNS-involved PTLD, EBV encephalitis is reported to appear hyperintense on plain T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI (30). Because EBV-DNA was detected in the CSF and cranial MRI T2-weighted and FLAIR revealed a high-intensity cerebral cortex without masses or peritumoral edema, we suspected our patient of having EBV encephalitis and not EBV-LPD with CNS involvement.

In conclusion, we reported a case of EBV-LPD with EBV encephalitis following ATG therapy in a patient with aplastic anemia who was successfully treated using rituximab. This case demonstrates that, in patients with aplastic anemia who are treated using ATG therapy, the initial symptoms of EBV-LPD should be considered. Because EBV-LPD following treatment for aplastic anemia progresses more rapidly than PTLD, weekly monitoring of EBV-DNA may be necessary. If EBV-LPD develops during treatment for aplastic anemia, a reduction in immunosuppressive treatment may be insufficient; therefore, preemptive treatment using rituximab should be considered.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained form the patient for publication.

Author contributions

KM, SY, and HY were the physicians in charge of the case. All of the authors contributed to the composition of this article and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We thank Ms. Yumiko Inui (Kobe University) for the useful advice regarding our medical practice.

References

- 1. Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med 350: 1328-1337, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Volume 2. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Landgren O, Gilbert ES, Rizzo JD, et al. Risk factors for lymphoproliferative disorders after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 13: 4992-5001, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meijer E, Slaper-Cortenbach IC, Thijsen SF, Dekker AW, Verdonck LF. Increased incidence of EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders after allogeneic stem cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors due to a change of T cell depletion technique. Bone Marrow Transplant 29: 335-339, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Velden WJ, Mori T, Stevens WB, et al. Reduced PTLD-related mortality in patients experiencing EBV infection following allo-SCT after the introduction of a protocol incorporating pre-emptive rituximab. Bone Marrow Transplant 48: 1465-1471, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rasche L, Kapp M, Einsele H, Mielke S. EBV-induced post transplant lymphoproliferative disorders: a persisting challenge in allogeneic hematopoetic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 49: 163-167, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sugimori C, Chuhjo T, Feng X, et al. Minor population of CD55-CD59- blood cells predicts response to immunosuppressive therapy and prognosis in patients with aplastic anemia. Blood 107: 1308-1314, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camitta BM. What is the definition of cure for aplastic anemia? Acta Haematol 103: 16-18, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marsh JC, Ball SE, Cavenagh J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol 147: 43-70, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Esser JW, van der Holt B, Meijer E, et al. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation is a frequent event after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) and quantitatively predicts EBV-lymphoproliferative disease following T-cell-depleted SCT. Blood 98: 972-978, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scheinberg P, Fischer SH, Li L, et al. Distinct EBV and CMV reactivation patterns following antibody-based immunosuppressive regimens in patients with severe aplastic anemia. Blood 109: 3219-3224, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Viola GM, Zu Y, Baker KR, Aslam S. Epstein-Barr virus-related lymphoproliferative disorder induced by equine anti-thymocyte globulin therapy. Med Oncol 28: 1604-1608, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raghavachar A, Ganser A, Freund M, Heimpel H, Herrmann F, Schrezenmeier H. Long-term interleukin-3 and intensive immunosuppression in the treatment of aplastic anemia. Cytokines Mol Ther 2: 215-223, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wondergem MJ, Stevens SJ, Janssen JJ, et al. Monitoring of EBV reactivation is justified in patients with aplastic anemia treated with rabbit ATG as a second course of immunosuppression. Blood 111: 1739, author reply; 1739-1740, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohata K, Iwaki N, Kotani T, Kondo Y, Yamazaki H, Nakao S. An Epstein-Barr virus-associated leukemic lymphoma in a patient treated with rabbit antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine for hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia. Acta Haematol 127: 96-99, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Calistri E, Tiribelli M, Battista M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in a patient treated with anti-thymocyte globulin for severe aplastic anemia. Am J Hematol 81: 355-357, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Viola GM, Zu Y, Baker KR, Aslam S. Epstein-Barr virus-related lymphoproliferative disorder induced by equine anti-thymocyte globulin therapy. Med Oncol 28: 1604-1608, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sugimoto-Sekiguchi H, Tashiro H, Shirasaki R, et al. Colonic EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorder in a patient treated with rabbit antithymocyte globulin for aplastic anemia. Case Rep Gastrointestl Med 2012: 395801, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakanishi R, Ishida M, Hodohara K, et al. Occurrence of Epstein-Barr virus-associated plasmacytic lymphoproliferative disorder after antithymocyte globulin therapy for aplastic anemia: a case report with review of the literature. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology 7: 1748-1756, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takahashi Tohru, Maruyama Yumiko, Saitoh Mayuko, Itoh Hideto, Yoshimoto Mitsuru, Tsujisaki Masayuki. Fatal Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in an acquired aplastic anemia patient treated with rabbit antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine. A Case Reports in Hematology Volume, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hanaoka N, Murata S, Hosoi H, et al. B-cell-rich T-cell lymphoma associated with Epstein-Barr virus-reactivation and T-cell suppression following antithymocyte globulin therapy in a patient with severe aplastic anemia. Hematol Rep 7: 5906, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsukamoto S, Nagao Y, Yamazaki A, et al. Successful allogeneic stem cell transplantation for severe aplastic anemia after treatment of lymphoproliferative disorder caused by rabbit antithymocyte globulin. Intern Med 54: 3197-3200, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Styczynski J, Reusser P, Einsele H, et al. Management of HSV, VZV and EBV infections in patients with hematological malignancies and after SCT: guidelines from the Second European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 43: 757-770, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bollard CM, Rooney CM, Heslop HE. T-cell therapy in the treatment of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 9: 510-519, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Worth A, Conyers R, Cohen J, et al. Pre-emptive rituximab based on viraemia and T cell reconstitution: a highly effective strategy for the prevention of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease following stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematology 155: 377-385, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Styczynski J, Gil L, Tridello G, et al. Response to rituximab-based therapy and risk factor analysis in Epstein Barr Virus-related lymphoproliferative disorder after hematopoietic stem cell transplant in children and adults: a study from the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 57: 794-802, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xuan L, Jiang X, Sun J, et al. Spectrum of Epstein-Barr virus-associated diseases in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation 96: 560-566, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castellano-Sanchez AA, Li S, Qian J, Lagoo A, Weir E, Brat DJ. Primary central nervous system posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Am J Clin Pathol 121: 246-253, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kempf C, Tinguely M, Rushing EJ. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder of the central nervous system. Pathobiology 80: 310-318, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kalita J, Maurya PK, Kumar B, Misra UK. Epstein Barr virus encephalitis: clinical diversity and radiological similarity. Neurology India 59: 605-607, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]