Abstract

Chronic stressors can often lead to the development of psychological disorders, such as depression and anxiety. The locus coeruleus (LC) is a stress sensitive brain region located in the pons, with noradrenergic neurons that project to the hypothalamus, especially the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus. The purpose of this paper is to better understand how alpha 2A-adrenoceptors (α2A-ARs) and LC-hypothalamus noradrenergic system participate in the pathophysiological mechanism of depression. In vivo norepinephrine (NE) release in the PVN triggered by electrical stimulation in the LC was detected with carbon fiber electrodes in depression model of rats induced by chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS). Also, the extracellular level of NE in the PVN was measured by microdialysis in vivo without any stimulation in the LC. The alpha 2-adrenoceptor (α2-AR) antagonist yohimbine and α2A-ARs antagonist BRL-44408 maleate were systemically administered to rats to determine the effects of α2A-ARs on NE release in the PVN. The peak value of elicited NE release signals in the PVN induced by electrical stimulation in the LC in the CUMS rats were lower than that in the control rats. The extracellular levels of NE in the PVN of the CUMS rats were significantly less than that of the control rats. Intraperitoneal injection of yohimbine or BRL-44408 maleate significantly potentiated NE release in the PVN of the CUMS rats. The CUMS significantly increased protein expression levels of α2A-AR in the hypothalamus, and BRL-44408 maleate significantly reversed the increase of α2A-AR protein expression levels in the CUMS rats. Our results suggest that the CUMS could significantly facilitate the effect of α2-adrenoceptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition and decrease the release of NE in the PVN from LC. Blockade of the inhibitory action of excessive α2A-adrenergic receptors in the CUMS rats could increase the level of NE in the PVN, which is effective in the treatment of depressive disorders.

Keywords: depression, locus coeruleus, hypothalamus, α2A-ardrenergic receptor, norepinephrine

Introduction

Depression, a widespread mental disorder, influences over 10% of the world's population with profound social and economic consequences at any given time (Ferrari et al., 2014). Even though stress and monoamine neurotransmitter deficiency have been studied as two major causes of depression (Andrus et al., 2012) and researchers over the last 50 years have provided considerable evidence that the dysfunction of monoamine neurons is an important underlying pathology in major depressive disorder (Hamon and Blier, 2013), the detailed mechanisms related to its pathogenesis are still elusive. As a result, a number of patients fail to recover from chronic depression even though lots of medications have been applied to clinical treatment for depressive disorders, including NE reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and antidepressants on DNA methylation patterns, etc. (Baudry et al., 2010; Massart et al., 2012; Kato and Chang, 2013).

Stress response is a risk factor that can develop anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other affective or mental disorders, which is characterized by the activation of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine (LC-NE) system (Altman et al., 1999; Ding et al., 2014). Stress can trigger the firing activity of noradrenergic neurons in the LC and subsequently widespread of NE transmission in the hypothalamus, prefrontal cortex, brainstem, cerebellum and amygdala (Liddell et al., 2005). The dysregulation of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus contributes to behavioral and physiological alterations caused by chronic stress, and NE plays a prominent role in the PVN activation (Herman et al., 2008; Flak et al., 2014). Adrenergic receptors are located widely in the central nervous system and can be activated by NE. Three known alpha 2-adrenoceptor (α2-AR) subtypes, α2A-AR, α2B-AR and α2C-AR, are distributed in mammalian brain tissues (Bylund et al., 1994; Alexander et al., 2015), of which α2A-AR was identified as the predominant inhibitory autoreceptor in adrenergic neurons (Trendelenburg et al., 1993). Existing studies also demonstrate that both α2A-AR and α2C-AR subtypes play a role as presynaptic inhibitory receptors regulating neurotransmitter release, and α2A-AR subtype contributes more to presynaptic negative feedback inhibition of NE release in mice (Altman et al., 1999; Bücheler et al., 2002; Gyires et al., 2009). Lacking the α2A-AR in mice, presynaptic autoinhibition mediated by endogenous NE or α2-receptor agonists was significantly blunted but not absent (Altman et al., 1999).

We hypothesized that LC noradrenergic neurons projecting to the hypothalamus (PVN) may functionally participate in the pathogenesis of depression and the α2A-AR plays a principal role by modulating NE release. To confirm the hypothesis, we measured the NE release signal in the PVN evoked by electrical stimulation in LC through amperometric detection with carbon fiber electrode. We also detected the extracellular level of NE in the PVN by microdialysis in vivo. Western blot analysis was carried out to evaluate the expression level of α2A-AR in the hypothalamus.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 180–200 g (purchased from Animal center of Nanjing Qinglongshan and the Animal Experimental Center of Dalian Medical University) were used in our research. Animals were housed at the conventional dwelling unit under standard conditions (5 per cage, room temperature of 24°C, relative humidity of 45–65%, 12 h light/dark cycle), ad libitum. All experiments were carried out under the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Chronic unpredictable mild stress model

Rats were divided into chronic unpredictable mild stresses (CUMS: rats exposed chronically to a variety of mild unpredictable stressors for 4 weeks) group (n = 20) and control group (n = 20) randomly (Willner et al., 1987). Each rat which belonged to the CUMS group was housed in one cage and subjected to one stressor one time a day (stressors included: water deprivation (15-h), cage tilt at a 45 degree angle (2-h), housing in mild damp sawdust (20-h), horizontal vibration (5-min), food deprivation (15-h), forced swim in water at 21°C (30-min) and intermittent white noise (85 dB, 3-h). All stressors lasted for 4-w and were applied at different points of time every week to avoid habituation and to provide an unanticipated feature to the stressors as described in detail previously (Shao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). The control rats were housed in bigger cages (5 rats per cage) and they remained socially active.

Behavioral tests

Behavioral tests included sucrose consumption test and open-field test. Sucrose consumption test was carried out as follows: two bottles of 1% sucrose water were randomly located in every cage at the first 2 days, which were turned into two bottles of tap water at the third day. Following with 15-h deprivation of food and water intake, a bottle of tap water and a bottle of 1% sucrose water were given to the rats. The consumption amount of 1% sucrose and total water were measured in the next 2-h. The sucrose preference percentage was calculated according to the following formula: Sucrose preference = sucrose intake (g)/[(sucrose intake (g) +water intake (g)] (Cui et al., 2014).

Open-field test was carried out to all the rats. Each rat was placed in the center of a white square box (length, 55 cm; width, 39 cm; height, 20 cm) for a 5-min observation. During the 5-min observation, horizontal and vertical exploratory locomotor activities were scored for the test.

Amperometric detection of NE signals with carbon fiber electrode

Amperometric detection of NE signals with carbon fiber electrode was performed according to our previously described method (Gong et al., 2015). Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.), and fixed at the stereotaxic instrument (Life Technology Co. Ltd. of Shenzhen City). A bipolar stainless steel electrode (diameter: 1.0 mm) sent electrical stimulation (Isolated Pulse Stimulator model 2100; A-M Systems) into LC (A: − 10.0 mm; L: ± 1.4 mm; V: − 7.5 mm) according to the rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). The amperometry working electrode was a cylindrical carbon-fiber electrode insulated by a glass capillary. The detecting carbon fiber electrode was inserted into the PVN (A: − 1.5 mm; L: ± 0.4 mm; V: − 8.5 mm). The reference electrode was a silver wire coated with AgCl and connected to the neck muscle tissue. A patch-clamp amplifier (PC-2B, INBIO, Wuhan, China) was applied under voltage-clamp mode, with the gain of 0.5 mV/pA and a CFE voltage of a constant + 700 mV for amperometry. All data were low pass filtered at 20 Hz and acquired by a data acquisition system with a digital interface and software (iPDA-0.1; INBIO, Wuhan, China). Norepinephrine release signals evoked by electrical stimulation (1.0 mA, 100 Hz, 100 pulses) in LC in vivo were analyzed. After recording stable NE signal, yohimbine (Sigma–Aldrich, 3 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) (Paalzow and Paalzow, 1983; McAllister, 2001) was administered to the rat and NE release signal was recorded again 30 min later to assess the function of α2-AR. The rats were euthanized with isoflurane and the whole brains were fixed in 10% formalin solution to verify the brain region.

In vivo microdialysis

In vivo microdialysis was carried out according to a previously described method (Niwa et al., 2007). Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and were fixed in a stereotactic instrument (Life Technology Co. Ltd. of Shenzhen City). The intracerebral guide cannula (MBR-10, BASI, West Lafayette, IN 47906, USA) was implanted 1 mm above the PVN (A: − 1.5 mm, L: ± 0.4 mm; V: − 8.5 mm) and was secured onto the skull by stainless screws and dental acrylic cement. After 24 h, a microdialysis probe (MBR-1-10, 1 mm membrane length, BASI) was embedded into the guide cannula, and the ACSF was continuously perfused into the PVN through the probe. During the microdialysis experiments, dialysates were collected in 1-h increments at a velocity of 1 μL/min, and then 50 μL aliquots were used to measure NE levels with an ELISA kit (CSB-E07022r, CUSABIO, Wuhan, China). BRL-44408 maleate (Sigma-Aldrich, 3 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered to rats and NE dialysates were collected again to assess the function of α2A-AR (Miksa et al., 2009).

Western blot studies

The protein from the hypothalamus (the hypothalamic tissue was dissected as the center between gray nodules and optic chiasma prechiasmal border as prozone, back of corpus albicans as posterior and bitemporal groove on both sides; about 4 mm width, 2 mm depth and 4 mm length) was extracted by using an extraction kit (Keygen Biotech, China), and the protein content was measured by a BCA protein assay (Keygen Biotech, China). For Western Blotting, the proteins (20 μg) for each sample were loaded into a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis. Then, the protein components were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and then blocked with 5% BSA in TBST (TBS+0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h, and then immunoblotted overnight at 4°C with primary antibody for α2A-AR (#14266-1-AP, Proteintech, USA). Subsequently, membranes were washed three times in TBST and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit, 1:5,000, ZSJQ-BIO Company, Beijing, China) for 1 h at room temperature. The infrared band signals were detected using BIO-RAD (Hercules, CA, USA) gel analysis software. The blots were then washed with TBST, blocked for 1 h and incubated with the primary antibody β-actin (ab6276, Abcam), for loading control. The Densitometric analysis of immunoreactivity was conducted using the NIH Image J software and normalized to the immunoreactivity of the control rats.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc.) and SPSS 21.0, expressed as mean ± SEM., and statistical analyses were performed using a paired t-test or an unpaired Student's t-test for two-sample comparison, two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of antagonists between groups (Figures 2C, 3B, 4B), and the microdialysis data summarized in Figure 3A were assessed by repeated-measures ANOVA. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Rat-specific depressive behavior induced by CUMS

After 4 weeks of CUMS, rats in the model showed a significant reduction in body weight compared to that in the control rats (p < 0.01, n = 20, respectively). Sucrose preference is frequently used as a measure of anhedonia in rodents (Gilsbach et al., 2009). Significant reductions of sucrose intake (p < 0.01) and sucrose preference (p < 0.05) were detected in the CUMS rats. The rats of CUMS group showed a significant reduction in the horizontal (p < 0.01) and vertical (p < 0.05) exploratory locomotor activity (Table 1).

Table 1.

The body weight, open-field test and sucrose consumption test in the two groups rats after modeling (n = 20, mean ± SEM).

| Body weight (g) | Open field test | Sucrose consumption | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal score | Vertical score | Total score | Sucrose (g) | Total (g) | Sucrose preference (%) | ||

| Control | 306.34 ± 7.2 | 37.3 ± 3.96 | 14.5 ± 2.03 | 51.8 ± 5.47 | 9.2 ± 0.87 | 12.74 ± 0.99 | 71.9 ± 2.6 |

| CUMS | 268.86 ± 4.88** | 16.9 ± 1.35** | 7.9 ± 1.32* | 24.8 ± 1.50** | 5.6 ± 0.40** | 8.76 ± 0.68** | 64.1 ± 2.2* |

CUMS produced a significant decrease in the body weight, horizontal and vertical exploratory locomotor activity, sucrose intake and sucrose preference in the CUMS rats compared to that in the control rats (

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01).

In our experiment, the CUMS rats showed significantly lower body weight, less locomotor activity in the open field test and lower sucrose preference ratio in the sucrose consumption test than that of the control rats after CUMS, which meant the CUMS induced depression successfully.

The LC-PVN noradrenergic system participated in the depression induced by CUMS

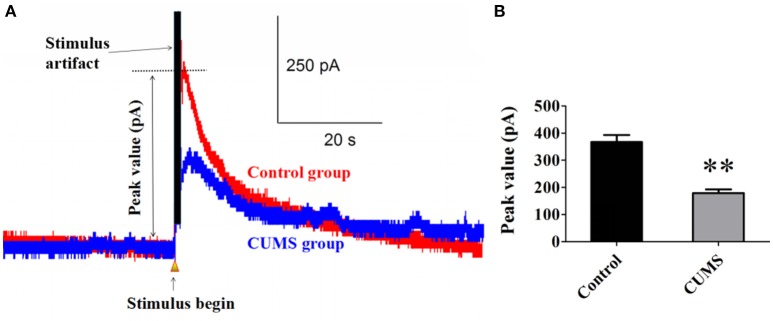

Norepinephrine is the main neurotransmitter in noradrenergic system. Elicited NE release from noradrenergic nerve fibers in the PVN induced by electrical stimulation in LC was detected with carbon fiber electrode. The data showed that chronic stresses significantly decreased the peak value of elicited NE release signal. There were statistical differences between the CUMS group and control group (179.1 ± 13.5 pA vs. 367.1 ± 26.2 pA, n = 9, p < 0.01. Figures 1A,B). This result demonstrated that the LC-PVN noradrenergic system participated in the CUMS-induced depression.

Figure 1.

CUMS significantly decreased the peak value of elicited NE release signal (A) Representative raw data of typical NE release signals recorded in the control and CUMS group rats. The peak value was labeled in figure. (B) The peak value of NE signal in the PVN was significantly decreased in the CUMS rats. **p < 0.01 vs. the control group rats.

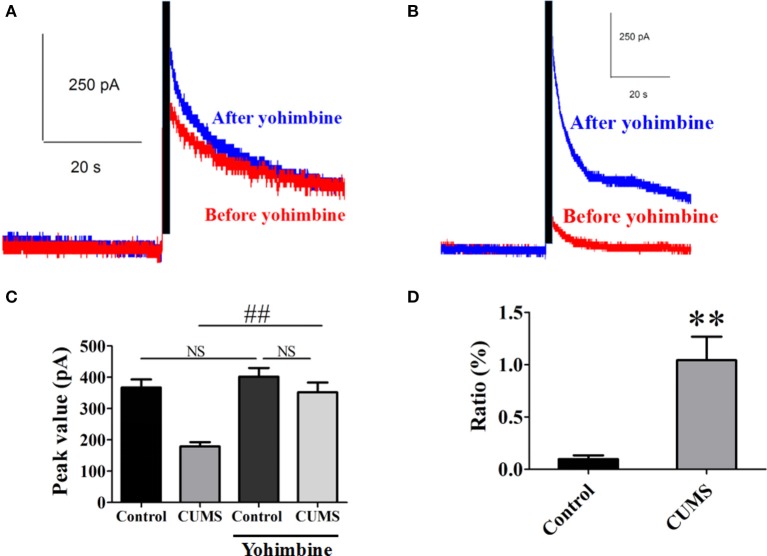

The α2-AR participated in pathophysiology of depression induced by the CUMS

Yohimbine is one of the α2-AR antagonists. Intraperitoneal administration of yohimbine (3 mg/kg, i.p.), potentiated the peak value of NE release signal in the PVN of each group of rats evoked by electrical stimulation in LC [for CUMS group, 351.9 ± 31.2 pA vs. 179.1 ± 13.5 pA, n = 9, p < 0.01; for control group, 401.8 ± 28.2 pA vs. 367.1 ± 26.2 pA, n = 9, p > 0.05. F(3, 32) = 15.76. Figures 2A–C]. The ratio of increase in the peak value of NE release signal in the CUMS rats was significantly amplified after the yohimbine administration compared to that in the control rats (104.3 ± 22.5% vs. 99% ± 3.5%, n = 9, p < 0.01. Figure 2D). These results confirmed that α2-AR acted to inhibit NE release and participated in the pathophysiology of depression induced by the CUMS.

Figure 2.

Intraperitoneal injection of yohimbine potentiated elicited NE release signal in the CUMS rats. (A) Representative raw data of typical NE release signals recorded in the control rats before and after yohimbine. (B) Representative raw data of typical NE release signals recorded in the CUMS rats before and after yohimbine. (C) Yohimbine significantly increased the peak value of NE in the PVN of the CUMS rats, but no significant difference was observed in the control rats. (D) The ratio of increase in the peak value of NE signal was significantly amplified after administration of yohimbine in the CUMS rats compared to that in the control rats. The ratio: [(after-before)/before yohimbine]. **p < 0.01 vs. the control rats, ##p < 0.01 vs. before yohimbine administration in the CUMS group. NS represents no significance.

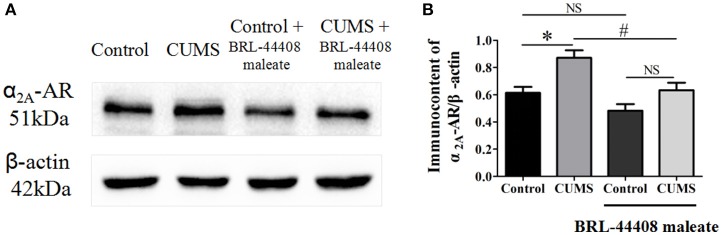

Effects of BRL-44408 maleate on the extracellular level of NE in the PVN

The dialysate concentration of NE was significantly decreased in the first (3.7 ± 0.4 vs. 5.3 ± 0.4, p < 0.05, n = 5) and the third hour (3.5 ± 0.3 vs. 5.2 ± 0.4, p < 0.05, n = 5) in the CUMS rats compared to that in the control rats, no significant difference was observed in the second and forth hour (Figure 3A). Repeated-measures ANOVA demonstrated a significant group × time interaction for NE [F(1.995, 7.982) = 4.996, p = 0.039], but no significance within-subjects effects (for time). Mean concentrations of NE in the PVN of the CUMS rats were less than that of the control rats [3.1 ± 0.3 vs. 4.3 ± 0.4, p < 0.05, n = 5. F(3, 16) = 5.973. Figure 3B].

Figure 3.

Intraperitoneal injection of BRL-44408 maleate can reverse the decrease of NE release induced by CUMS. (A) The dialysate concentration of NE were less in the first and third hour in the CUMS rats than that in the control rats, intraperitoneal injection of BRL-44408 maleate increased extracellular level of NE in both group of rats, but no significance was observed between the two groups. (B) The CUMS significantly decreased the mean levels of extracellular NE in the PVN of the CUMS rats compared to that in the control rats, but no significance was observed between the two groups after BRL-44408 maleate. (C) The ratio of increase in the NE release was significantly amplified after administration of BRL-44408 maleate in the CUMS rats compared to that in the control rats. The ratio: [(after-before)/before BRL-44408 maleate]. Δ: BRL-44408 maleate administration (3 mg/kg, i.p.). *p < 0.05 vs. the control rats. NS represents no significance.

The alpha 2A-adrenoceptors antagonist BRL-44408 maleate significantly amplified the ratio of increase [(after-before)/before BRL-44408 maleate] of NE in the CUMS rats compared to that of the control rats (22.8 ± 7.4% vs. 2.7 ± 1.4%, n = 5, p < 0.05. Figure 3C). These results suggest the inhibitory action of α2-AR on LC-PVN noradrenergic system maybe partly through α2A-AR subtype in the CUMS rats.

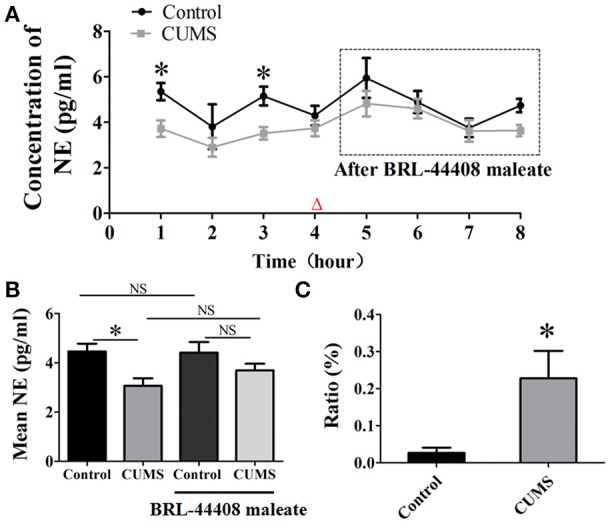

Western blot studies

The protein expression levels of α2A-AR (observed at 51 kDa) was significantly increased in the hypothalamus of the CUMS rats compared to that of the control rats (0.87 ± 0.05 vs. 0.61 ± 0.04, p < 0.05, n = 5). BRL-44408 maleate significantly decreased the α2A-AR protein level in the CUMS rats (0.63 ± 0.05 vs. 0.87 ± 0.05, p < 0.05, n = 5), but no significance was observed in the control rats (0.48 ± 0.05 vs. 0.61 ± 0.04, p > 0.05, n = 5). [F(3, 16) = 12.18, Figure 4]. The results demonstrated that CUMS increased α2A-AR level in the hypothalamus and the increased quantity of α2A-AR contributes to decreased NE release in the hypothalamus.

Figure 4.

Intraperitoneal injection of BRL-44408 maleate can reverse the increase of α2A-AR induced by CUMS in the hypothalamus of the CUMS rats. (A.B) The protein expression levels of α2A-AR was significantly increased in the hypothalamus of the CUMS rats, peripheral administration of BRL-44408 maleate significantly decreased the expression levels of α2A-AR in the CUMS rats. *p < 0.05 vs. the control rats. #p < 0.05 vs. before BRL-44408 maleate in the CUMS group. NS represents no significance.

Discussion

The CUMS model was developed based upon the hypothesis of depression induced by stress. Antidepressants agents can reverse most effects of CUMS, illustrating a strong predictive validity of this model for depression. However, the mechanisms underlying the CUMS are still not understood completely. Our results showed that the CUMS significantly decreased the peak value of elicited NE release in the PVN evoked by electrical stimulation in LC, which illustrated that the secretion of NE from LC projecting to the PVN nerve fiber endings were decreased in the CUMS rats compared to that in the control rats.

Stressors can damage LC (Samuels and Szabadi, 2008). Moreover, damage or loss of LC noradrenergic neurons could result in the decrease of NE in the central nervous system (Marien et al., 2004; Rommelfanger and Weinshenker, 2007; Weinshenker, 2008). In our study, we found yohimbine, α2-AR antagonist (Makau et al., 2016), significantly increased the peak value of elicited NE release from noradrenergic nerve fibers in the PVN evoked by electrical stimulation in LC in the CUMS rats. It is generally recognized that the α2-adrenergic receptors are coupled with the inhibitory guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-binding protein, which may be involved in the receptor-mediated transmembrane signaling by regulating adenylate cyclase activity (Tsuda et al., 2003). This further weakens the calcium current mediated by voltage-gated calcium channels and the potassium current reliant on the calcium ions, then causes a decrease in the concentration of cytoplasm Ca2+, in turn inhibits the synthesis and release of NE (Abdulla and Smith, 1997). Yohimbine increases the release of NE in the PVN by inhibiting the signaling pathway of α2-AR, suggesting that the functional change of the presynaptic membrane α2 receptor has a connection with the targets for the treatment of depression.

We used microdialysis to estimate the extracellular level of NE in the PVN in order to confirm the decreased NE level in the PVN of the CUMS rats and eliminate the interference of 5-HT and dopamine in the amperometric detection of NE. The results showed that the CUMS significantly decreased the levels of NE in the PVN, and selective α2A-ARs antagonist BRL-44408 maleate significantly increased the levels of NE in the PVN of the CUMS rats compared to that in the control rats. Our data suggest that blockade of α2A-adrenergic receptor can increase the level of NE in the PVN. In vivo dialysate measured by microdialysis showed α2A-adrenergic receptor agonist clonidine decreased the level of NE in the prefrontal cortex (Doucet et al., 2013), LC and cingulate cortex (Mateo et al., 2001), which also indicate that NE release might be highly dependent on the α2A-adrenergic receptors. Hence, the anomaly of α2A-ARs maybe a physiopathology mechanism to trigger depressive disorder through direct or indirect effects to the secretion of NE in the PVN and the firing of LC noradrenergic neurons (Aoki et al., 1994; Nörenberg et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1998; Guiard et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009).

The results showed that the expression levels of α2A-AR in the hypothalamus were significantly increased in the CUMS rats compared to that in the control rats, and the up-regulated effects of α2A-AR were significantly reversed by the acute administration of BRL-44408 maleate. These findings suggest that the CUMS up-regulates the quantity of α2A-AR and the α2A-ARs antagonist, BRL-44408 maleate, may block the activities of α2A-ARs. Post mortem studies in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and LC of depressed patients revealing up-regulation of α2A-ARs, and elevated α2A-ARs RNA expression in the glutamatergic neurons induced by chronic stress (Flügge et al., 2003). However, α2A-AR knockout mice showed depressive-like behavior that was not responsive to imipramine, and therefore was concluded that α2A-AR has antidepressive effects (Schramm et al., 2001). This reminds us that the increase in α2A-AR expression in the CUMS rats might be regarded as a compensatory rebound effect, possibly because of decreased amounts of NE primarily at sites distant from the LC. Excessive expression of α2A-AR may suppress adrenaline-induced (cAMP)i increase and exocytosis (Harada et al., 2015). Since α2A-ARs are generally coupled with Gαi/o proteins, the overexpression of α2A-AR can promote Gi function, resulting in the inhibition of cAMP production and a series of intracellular signal transmission, eventually leading to inhibition of neuron activity and NE secretion. In our study, the increased expression levels of α2A-AR in the CUMS rats may have induced the inhibition of the secretion of NE through activation of Gi protein signal pathway (Wu and Saggau, 1997; Brown and Sihra, 2008). The alpha 2A-adrenoceptors antagonist BRL-44408 maleate blocked the excessive α2A-AR and down-regulated the quantity of α2A-AR, which could weaken or eliminate its inhibitory effect to NE release.

However, although α2A-ARs contributes the significantly inhibitory effect on NE release, other subtypes of α2-AR, such as α2B-AR and α2C-AR may have less effect on NE release, indicating that α2-adrenoceptors antagonists might be better drugs for the treatment of depression. It also cannot be ignored that yohimbine also augmented anxiety both in human and rodents (Davis et al., 1979; Morgan et al., 1993; Altobelli et al., 2001), and the enhanced central noradrenergic activity is associated with the activation of fear and anxiety circuitries. This paradox may precisely result from the increase of NE by yohimbine, which may induce the activation of stimulatory α1- and of β-adrenergic receptor, the latter may mediate the enhancement of neuronal activity and further induce the activation of anxiety (Montoya et al., 2016). Hence, the dose and duration of α2-adrenoceptor antagonists for the treatment of depression require future research.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the CUMS could significantly facilitate the effect of α2-adrenoceptors-mediated presynaptic inhibition and decrease the release of NE in the PVN from LC. Blockade of the inhibitory action of the excessive α2A-adrenergic receptor in the CUMS rats could increase the level of NE in the PVN, which is effective in the treatment of depressive disorders.

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23) revised 1996. All experimental protocols were approved by the animal studies committees of the Dalian Medical University and the committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Wannan Medical College, and all efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Author contributions

BW: Substantial contributions to design of the work; the acquisition of data for the work; writing of the article. YW: Assist the experiment to finish, the analysis and interpretation of data for the work. QW: Assist the experiment to finish, initial article revision. HH: Contributions to the conception of the work, ultima article revision. SL: Contributions to the conception of the work, final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571061, 8167106, 30770674, 81371223 and 81371437), the 4th Anhui Province Excellent Youth Grant, China (08040106817).

References

- Abdulla F. A., Smith P. A. (1997). Ectopic alpha2-adrenoceptors couple to N-type Ca2+ channels in axotomized rat sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 17, 1633–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander S. P., Davenport A. P., Kelly E., Marrion N., Peters J. A., Benson H. E., et al. (2015). The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: g protein-coupled receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172, 5744–5869. 10.1111/bph.13348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J. D., Trendelenburg A. U., MacMillan L., Bernstein D., Limbird L., Starke K., et al. (1999). Abnormal regulation of the sympathetic nervous system in α2A-adrenergic receptor knockout mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 56, 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altobelli D., Martire M., Maurizi S., Preziosi P. (2001). Interaction of formamidine pesticides with the presynaptic alpha-adrenoceptor regulating. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 172, 179–185. 10.1006/taap.2001.9158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrus B. M., Blizinsky K., Vedell P. T., Dennis K., Shukla P. K., Schaffer D. J., et al. (2012). Gene expression patterns in the hippocampus and amygdala of endogenous depression and chronic stress models. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 49–61. 10.1038/mp.2010.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C., Go C. G., Venkatesan C., Kurose H. (1994). Perikaryal and synaptic localization of α2A-adrenergic receptor-like immunoreactivity. Brain Res. 650, 181–204. 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91782-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry A., Mouillet-Richard S., Schneider B., Launay J. M., Kellermann O. (2010). miR-16 targets the serotonin transporter: a new facet for adaptive responses to antidepressants. Science 329, 1537–1541. 10.1126/science.1193692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. A., Sihra T. S. (2008). Presynaptic signaling by heterotrimeric G-proteins. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 184, 207–260. 10.1007/978-3-540-74805-2_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bücheler M. M., Hadamek K., Hein L. (2002). Two α-adrenergic receptor subtypes, α2A and α2C, inhibit transmitter release in the brain of gene-targeted mice. Neuroscience 109, 819–826. 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00531-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund D. B., Eikenberg D. C., Hieble J. P., Langer S. Z., Lefkowitz R. J., Minneman K. P., et al. (1994). International Union of Pharmacology nomenclature of adrenoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 46, 121–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Li Q., Zhang M., Zhao Y. J., Huang F., Chen Y. J. (2014). Long-term curcumin treatment antagonizes masseter muscle alterations induced by chronic unpredictable mild stress in rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 59, 258–267. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M., Redmond D. E., Jr., Baraban J. M. (1979). Noradrenergic agonists and antagonists: effects on conditioned fear as measured by the potentiated startle paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 65, 111–118. 10.1007/BF00433036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X. F., Zhao X. H., Tao Y., Zhong W. C., Fan Q., Diao J. X. (2014). Xiao yao san improves depressive-like behaviors in rats with chronic immobilization stress through modulation of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014:605914. 10.1155/2014/605914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet E. L., Bobadilla A. C., Houades V., Lanteri C., Godeheu G., Lanfumey L., et al. (2013). Sustained impairment of α2A-adrenergic autoreceptor signaling mediates neurochemical and behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 90–98. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari A. J., Norman R. E., Freedman G., Baxter A. J., Pirkis J. E., Harris M. G., et al. (2014). The burden attributable to mental and substance use disorders as risk factors for suicide: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS ONE 9:e91936. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flak J. N., Myers B., Solomon M. B., McKlveen J. M., Krause E. G., Herman J. P. (2014). Role of paraventricular nucleus-projecting norepinephrine/epinephrine neurons in acute and chronic stress. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 1903–1911. 10.1111/ejn.12587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügge G., van Kampen M., Meyer H., Fuchs E. (2003). α2A and α2C-adrenoceptor regulation in the brain: α2A changes persist after chronic stress. Eur. J. Neurosci. 17, 917–928. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02510.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilsbach R., Röser C., Beetz N., Brede M., Hadamek K., Haubold M., et al. (2009). Genetic dissection of α2-adrenoceptor functions in adrenergic versus nonadrenergic cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 1160–1170. 10.1124/mol.109.054544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W. K., Lü J., Wang F., Wang B., Wang M. Y., Huang H. P. (2015). Effects of angiotensin type 2 receptor on secretion of the locus coeruleus in stress-induced hypertension rats. Brain Res. Bull. 111, 62–68. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiard B. P., El Mansari M., Merali Z., Blier P. (2008). Functional interactions between dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine neurons: an in-vivo electrophysiological study in rats with monoaminergic lesions. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 11, 625–639. 10.1017/S1461145707008383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyires K., Zádori Z. S., Török T., Mátyus P. (2009). α-Adrenoceptor subtypes-mediated physiological, pharmacological actions. Neurochem. Int. 55, 447–453. 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon M., Blier P. (2013). Monoamine neurocircuitry in depression and strategies for new treatments. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 45, 54–63. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada K., Kitaguchi T., Tsuboi T. (2015). Integrative function of adrenaline receptors for glucagon-like peptide-1 exocytosis in enteroendocrine L cell line GLUTag. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 460, 1053–1058. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.03.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J. P., Flak J., Jankord R. (2008). Chronic stress plasticity in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Prog. Brain Res. 170, 353–364. 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00429-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M., Chang C. M. (2013). Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs 27(Suppl. 1), S11–S19. 10.1007/s40263-012-0029-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A., Rosin D. L., Van Bockstaele E. J. (1998). α2A-adrenergic receptors in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus: subcellular localization in catecholaminergic dendrites, astrocytes, and presynaptic axon terminals. Brain Res. 795, 157–169. 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00266-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell B. J., Brown K. J., Kemp A. H., Barton M. J., Das P., Peduto A., et al. (2005). A direct brainstem-amygdala-cortical “alarm” system for subliminal signals of fear. Neuroimage 24, 235–243. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makau C. M., Towett P. K., Abelson K. S., Kanui T. I. (2016). Modulation of formalin-induced pain-related behaviour by clonidine and yohimbine in the Speke's hinged tortoise (Kiniskys spekii). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 1–8. 10.1111/jvp.12374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marien M. R., Colpaert F. C., Rosenquist A. C. (2004). Noradrenergic mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases: a theory. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 45, 38–78. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massart R., Mongeau R., Lanfumey L. (2012). Beyond the monoaminergic hypothesis: neuroplasticity and epigenetic changes in a transgenic mouse model of depression. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367, 2485–2494. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo Y., Fernández-Pastor B., Meana J. J. (2001). Acute and chronic effects of desipramine and clorgyline on α-adrenoceptors regulating noradrenergic transmission in the rat brain: a dual-probe microdialysis study. Br. J. Pharmacol. 133, 1362–1370. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister K. H. (2001). The α2 adrenoceptor antagonists RX 821002 and yohimbine delay-dependently impair choice accuracy in a delayed non-matching-to-position task in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 155, 379–388. 10.1007/s002130100736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miksa M., Das P., Zhou M., Wu R., Dong W., Ji Y., et al. (2009). Pivotal role of the α2A-adrenoceptor in producing inflammation and organ injury in a rat model of sepsis. PLoS ONE 4:e5504. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya A., Bruins R., Katzman M. A., Blier P. (2016). The noradrenergic paradox: implications in the management of depression and anxiety. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 541–57. 10.2147/NDT.S91311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C. A., III, Southwick S. M., Grillon C., Davis M., Krystal J. H., Charney D. S. (1993). Yohimbine-facilitated acoustic startle reflex in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 110, 342–346. 10.1007/BF02251291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M., Nitta A., Mizoguchi H., Ito Y., Noda Y., Nagai T., et al. (2007). A novel molecule “shati” is involved in methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion, sensitization, and conditioned place preference. J. Neurosci. 27, 7604–7615. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1575-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nörenberg W., Schoffel E., Szabo B., Starke K. (1997). Subtype determination of soma-dendritic α2-autoreceptors in slices of rat locus coeruleus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 356, 159–165. 10.1007/PL00005036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paalzow G. H., Paalzow L. K. (1983). Yohimbine both increases and decreases nociceptive thresholds in rats: evaluation of the dose-response relationship. Naunyn Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 322, 193–197. 10.1007/BF00500764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G., Watson C. (1986). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Sydney, NSW: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rommelfanger K. S., Weinshenker D. (2007). Norepinephrine: the redheaded stepchild of Parkinson's disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 74, 177–190. 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels E. R., Szabadi E. (2008). Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function part II: physiological and pharmacological manipulations and pathological alterations of locus coeruleus activity in humans. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 6, 254–285. 10.2174/157015908785777193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm N. L., McDonald M. P., Limbird L. E. (2001). The α2a-adrenergic receptor plays a protective role in mouse behavioral models of depression and anxiety. J. Neurosci. 21, 4875–4882. Available online at: http://www.jneurosci.org/content/21/13/4875.long [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao S. H., Shi S. S., Li Z. L., Zhao M. S., Xie S. Y., Pan F. (2010). Aging effects on the BDNF mRNA and TrkB mRNA expression of the hippocampus in different durations of stress. Chin. J. Physiol. 53, 285–293. 10.4077/CJP.2010.AMK056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg A. U., Limberger N., Starke K. (1993). Presynaptic α2-autoreceptors in brain cortex: α2D in the rat and α2A in the rabbit. Naunyn Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 348, 35–45. 10.1007/BF00168534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K., Tsuda S., Nishio I. (2003). Role of alpha2-adrenergic receptors and cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase in the regulation of norepinephrine release in the central nervous system of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 42(Suppl. 1), S81–S85. 10.1097/00005344-200312001-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. M., Yang L. H., Zhang Y. Y., Niu C. L., Cui Y., Feng W. S., et al. (2015). BDNF and COX-2 participate in anti-depressive mechanisms of catalpol in rats undergoing chronic unpredictable mild stress. Physiol. Behav. 151, 360–368. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Zhang Q. J., Liu J., Wu Z. H., Wang S. (2009). Firing activity of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons increases in a rodent model of Parkinsonism. Neurosci. Bull. 25, 15–20. 10.1007/s12264-009-1023-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker D. (2008). Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5, 342–345. 10.2174/156720508784533286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P., Towell A., Sampson D., Sophokleous S., Muscat R. (1987). Reduction of sucrose preference by chronic unpredictable mild stress, and its restoration by a tricyclic antidepressant. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 93, 358–364. 10.1007/BF00187257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. G., Saggau P. (1997). Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends Neurosci. 20, 204–212. 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)01015-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]