Abstract

Family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer often take on responsibilities that present daunting and complex problems. Serious problems that go unresolved may be burdensome and result in negative outcomes for caregivers’ psychological and physical health and affect the quality of care delivered to the care recipients with cancer, especially at the end of life. Formal problem-solving training approaches have been developed over the past several decades to assist individuals with managing problems faced in daily life. Several of these problem-solving principles and techniques were incorporated into ENABLE (Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life End), an ‘early’ palliative care telehealth intervention for individuals diagnosed with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. A hypothetical case resembling the situations of actual caregiver participants in ENABLE that exemplifies the complex problems that caregivers face is presented followed by presentation of an overview of ENABLE’s problem-solving key principles, techniques and steps in problem-solving support. Though more research is needed to formally test the use of problem-solving support in social work practice, social workers can easily incorporate these techniques into everyday practice.

Case Study

Susan is a 63 year old white female who was recently diagnosed with stage IIIC epithelial ovarian cancer after recent discovery of peritoneal metastases. Susan’s husband died five years ago and she now lives alone in her home of 40 years. Susan originally had surgery and radiation therapy when first diagnosed 5 years ago and had done well for several years but has recently developed increasing abdominal pain and swelling and tiredness. Susan’s primary caregiver is her son, Joe, who lives 20 minutes away in a neighboring town. Joe is a generally healthy 42 year old who works full-time as an electrician. Joe has been supporting his mother on a daily basis for about 2 months. He manages all of his mother’s medical appointments, medications and bills; drives and accompanies her to and from medical appointments; helps maintain his mother’s home and yard; and does her grocery shopping.

You have met Joe on several occasions when he has accompanied his mother to her clinic visits. He is married and has two children, a son who is a freshman in college and a daughter who is a sophomore in high school. Joe’s wife, Ann, is an elementary school teacher. You know from your conversations with Joe that his wife and mother have a conflicted relationship. Joe also has 2 younger brothers. One brother lives 3 hours away and the other lives across the country. Joe mentioned to you that he is not sleeping well and often feels “on edge” and exhausted. Though Joe is not explicitly seeking professional help, you believe he would be open to supportive counseling and other services if offered.

Surveying the Terrain of Joe’s Caregiver Problems

Like many caregivers, Joe is faced with a number of problems (see Table 1). Some are practical. Joe and Ann’s finances are strained from paying college tuition for their son. Moreover, Joe has exhausted all of his paid vacation days and now frequently misses work without pay to help get his mother to weekly medical appointments. He worries he will not be able to pay for his daughter’s tuition when she starts college in 2 years.

Table 1.

General Domains and Examples of Problem Areas experienced by Family Caregivers

| Practical | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Decisional | |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Interpersonal | |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Emotional | |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Physical | |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Existential/Spiritual/Religious | |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Some of Joe’s problems are interpersonal. Joe’s wife, Ann, and his mother have had a tenuous relationship since he and Ann married. Ann believes that Susan is domineering and ungrateful for the help Joe provides her. Ann makes daily remarks that make Joe feel guilty for helping his mother. On several occasions, she has chastised Joe over how late he comes home at night after commuting back from his mother’s house. Joe is also frustrated by the lack of support from his two brothers. His brother who lives 3 hours away by car has failed to show up on weekends to help when planned. Joe has had difficulty simply contacting his other brother who lives 6 hours away by plane due to his brother’s busy job.

Other problems are emotional. Joe is saddened by seeing his once vibrant and active mother become increasingly functionally limited. Her doctors have informed her that she has a limited life expectancy of about six months. Yet his mother seems to be in denial about her prognosis and avoids conversations with Joe concerning the future. Joe is worried about the kinds of medical decisions he may have to make on her behalf in the event she becomes too ill to make choices herself. At the same time, Joe is angry about the lack of support he gets from others, most especially his wife and brothers.

Joe is also having physical problems. Given the time demands of his daily caregiving responsibilities, Joe no longer has time to go bicycle riding. He is not eating well and picks up fast-food between his commutes to and from his mother’s house. Joe has gained 10 pounds over the past 4 months. The daily stress Joe experiences is also causing him to become sleep deprived. He wakes up several times each night worrying about everything he has to do the next day. This has impacted his concentration during the day and made him more irritable.

Finally, Joe has existential and spiritual problems. He often remarks to himself in private that he does not deserve this. He did not choose to take on this caregiving role and it feels like it was imposed on him. He is torn between a familial duty to support his mother and a feeling of unfairness and not being appreciated.

Overview of Advanced Cancer Family Caregivers

The American Cancer Society predicts that 589,430 individuals in the US will die from cancer in 2015 (American Cancer Society, 2015). Joe’s situation as a caregiver for someone with advanced cancer is not unique. In the year to months leading up to death, most care for these individuals will be provided by unpaid family members and friends. This care and support consumes an average of 8 hours a day (Yabroff & Kim, 2009) and includes tasks such as managing and monitoring symptoms, providing transportation, coordinating care, communicating with providers, managing medications, providing emotional and spiritual support, managing dietary needs, and assisting patients with decision-making (Bee, Barnes, & Luker, 2008; Stenberg, Ruland, & Miaskowski, 2010). Taken together, these tasks become burdensome. In combination with witnessing someone close to them struggle with illness, family caregivers have been found to experience psychological distress at a level greater than or equal to their care recipients with cancer (Hodges, Humphris, & Macfarlane, 2005; Palos et al., 2011). Studies have linked high levels of caregiver distress to depression (Hudson, Thomas, Trauer, Remedios, & Clarke, 2011), poor physical health (Palos et al., 2011; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2007), and higher mortality risk (Perkins et al., 2013). The Institute of Medicine (2013) and others (Evercare and National Alliance for Caregiving, 2006; Park et al., 2010) report that unmet caregiver needs lead to poor physical and mental health and can negatively impact their ability to provide care. Moreover, family caregivers are often not prepared for care recipient’s end of life (EOL). Often they do not make decisions concordant with patients’ wishes (Shalowitz, Garrett-Mayer, & Wendler, 2006) and frequently experience negative effects following the care recipient’s death, such as regret and complicated grief (Hudson et al., 2011; Thomas, Hudson, Trauer, Remedios, & Clarke, 2014; Wendler & Rid, 2011). The taxing role of family caregiving has thus been recognized as a public health crisis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008).

Adapting Problem-Solving Therapy in the ENABLE Intervention

A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) tested a telehealth, psychoeducational, palliative care intervention for persons with advanced and their family caregivers called ENABLE (Bakitas et al., 2015; Dionne-Odom et al., 2015). ENABLE stands for Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends. The ENABLE intervention is an early palliative care intervention delivered to patients and family caregivers at the time of advanced cancer diagnosis. As the disease progresses towards end of life, patients become sicker and more fatigued and caregivers become more entrenched with day-to-day tasks. This makes delivering interventions later in advanced cancer more challenging. In contrast, during the few months following diagnosis, patients and caregivers typically still feel relatively well. Hence, they may be more able to acquire knowledge (e.g. advance care planning, disease processes) and skills (e.g. tracking and managing symptoms at home) that they will need in the future.

In the most recent ENABLE trial, persons newly diagnosed with advanced cancer and their family caregivers were randomized to receive the intervention early (within 60 days of diagnosis) or delayed (12 weeks later). Compared to patients in the delayed group, early group patients demonstrated a higher survival rate at 1 year (63% vs. 48%, p=.038) (Bakitas et al., 2015). Caregivers in the early group had lower depressed mood (p=.02) and stress burden (p=.01) (Dionne-Odom et al., 2015). The intervention consisted of an in-person palliative care assessment for patients; weekly, psychoeducational telephone sessions for patients (6 sessions) and caregivers (3 sessions) facilitated by a palliative care interventionist; and monthly check-in phone calls. Palliative care interventionists in the trial were advanced practice nurses; however ENABLE is now being tested in an ongoing implementation study where social workers are successfully delivering the problem-solving components of the program. For ENABLE, patients and caregivers had their own separate interventionist and a separate curriculum focusing on their individual needs. Further details of the ENABLE intervention are published elsewhere (Bakitas et al., 2015; Dionne-Odom et al., 2015; Lyons et al., 2009; Skalla, Bakitas M, Furstenberg C, Ahles, & Henderson, 2004).

The ENABLE curriculum was first developed in 1999 through the use of focus groups conducted with patients and families. The intervention was further modified for delivery over the telephone in a demonstration project funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Maloney et al., 2013). The approach to problem-solving support in the ENABLE intervention was informed by two evidence-based approaches: The first was a highly structured, brief form of cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression called problem-solving treatment (Hegel, Dietrich, Seville, & Jordan, 2004; Unützer et al., 2002). Used mostly in primary medical care for short-term therapy of “here and now” problems, problem-solving treatment teaches participants over the course of 6-16 sessions with additional homework exercises how to identify and frame the problem, come up with realistic solutions, select the best possible solution, develop and implement an action plan, and assess how their problem-solving attempts were going. The second was McMillan’s COPE (Creativity, Optimism, Planning, Expert Information) intervention, which was derived from the conceptual foundations of problem-solving therapy (Loscalzo & Bucher, 1999; S. C. McMillan & B. J. Small, 2007; S. C. McMillan et al., 2005). COPE was developed specifically for caregivers of care recipients with chronic illness and emphasized the attitudes most characteristic of problem-focused coping as opposed to less constructive forms of coping including avoidant- (e.g. not thinking about the problem) and emotion-focused coping (e.g. blaming self) (Bucher & Zabora, 2010; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Based on these two approaches, a brief curriculum of problem-solving support was formulated for effective self-management of the problems (see Table 1) that arise for caregivers like Joe who care for someone with advanced cancer. The aims of our problem-solving support were to help participants: have a positive outlook; stop negative thoughts from getting them down; reason out loud and carefully about the problems they faced; prevent them from making rash or careless choices; and face problems directly instead of avoiding them. The rationale for problem-solving support including the COPE attitude and the 6 steps of problem-solving were introduced and covered in the first ENABLE session.

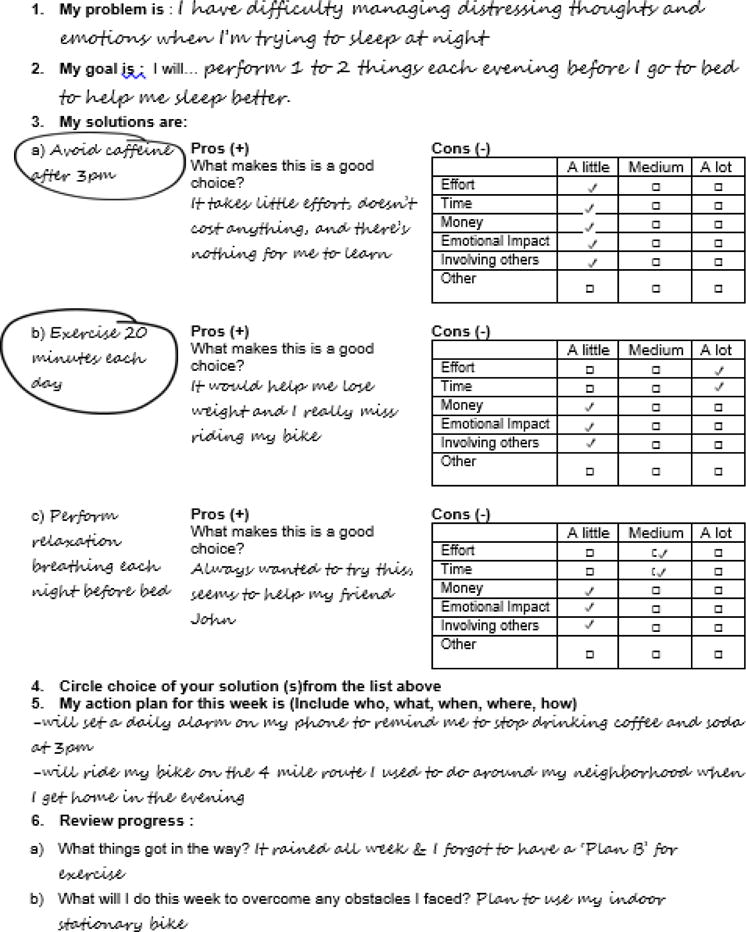

Participants were asked in this first session about any distress they were having and if so, what problems they thought might be causing it. For problems identified in this first session, participants engaged in the problem-solving steps using a problem-solving worksheet (see Figure 1) and were asked in subsequent sessions about their progress in employing solutions to manage their problems. For caregivers who did not have a specific problem they wanted to work in the first session, they were encouraged in subsequent ENABLE sessions and phone calls to address any problems they might encounter in the future using the COPE attitude and the 7 steps’ principles. Based on the most recent ENABLE trial, principles and steps are outlined in the following sections that were used in this intervention and practical advice is highlighted that may be of use to social workers and other clinicians who regularly encounter family caregivers like Joe.

Figure 1.

Example of Problem-Solving Worksheet

The ENABLE Problem-Solving Support Process

Introduction: Orient the Person to a Problem-Solving Attitude

In ENABLE, caregivers are encouraged to think of problems as opportunities or “calls to action.” Big problems often have no “right” answer. There can many different ways to address a problem, some of which are more helpful than others. Regardless of which particular strategies are chosen to solve a problem, people who are actively doing something about their problems tend to have a better mood and easier time functioning (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 2007). Hence, the first step in our ENABLE approach to problem-solving support is to orient individuals to a positive problem-solving attitude. Family caregivers like Joe are taught that when dealing with difficult problems, one’s attitude can impact whether problems get better or worse. Table 2 lists statements representing unhelpful attitudes people might have when faced with difficult problems. After showing individuals this list of unhelpful attitudes, a set of positive attitudes are introduced that can be more helpful at managing big problems. These positive problem-solving attitudes include creativity, optimism, planning, and expert information, or COPE (Loscalzo & Bucher, 1999; S. McMillan & B. Small, 2007; S. McMillan et al., 2005).

Table 2.

Unhelpful Attitudes when faced with Difficult Problems (from D’Zurilla and Nezu, 2007)

|

Creativity

Many of the problems faced by caregivers like Joe have never been faced before. This means Joe will need to be creative and brainstorm potential solutions. To help Joe do this, he would be encouraged to see his problems from someone else’s point of view: “Joe, what would one of your friends or co-workers do if they were in your situation?” Joe might be asked what things he has tried in the past for comparable problems. Joe might also benefit from seeking advice from people he knows, including his family, friends, neighbors, health care team, and other people who have dealt with similar issues. If a problem is particularly complex, individuals are urged to think about smaller parts of the problem that might be amenable to some control on their part. Finally people are encouraged to think “out-of-the-box” by having them consider ideas that seem “weird” and “unrealistic.” Keeping these kinds of ideas in mind and reflecting on them further might turn into viable, effective solutions.

Optimism

Optimism means that having a positive attitude towards dealing with problems will increase the odds of success. This does not mean minimizing individuals’ problems by presenting a rosy picture of their situation. In contrast, optimism still means that taking action to address problems takes time, energy, and strategizing. It means that putting energy into handling problems is better than pretending that problems do not exist. If caregivers like Joe think that a problem is hopelessly insurmountable, then it will hard for them to stay motivated to brainstorm and test potential solutions. Joe is reminded that nearly everyone, including himself, has dealt with big problems in the past (e.g. raising a child, getting a college degree) and that he can continue to do so in the future. Part of supporting a caregiver’s optimism also includes stressing the point that addressing smaller parts of a problem is better than not addressing any part.

Planning

Planning means thinking carefully about ways to address a problem in clear, concrete steps. Caregivers are informed of the advantages of getting ideas out of their head by writing their ideas down on paper. This might simply mean making a to-do list and a calendar of activities. Caregivers are taught to keep track on paper of how their plan is going, while also understanding that most plans are not perfect the first time around. Joe might be asked: “How are you going to know if your plan is working? How long of a trial period are you going to give a strategy a chance to work before you move on to something else?” Many plans to tackle problems involve information gathering and so caregivers are advised to be honest about what they do and do not know. It is also important for caregivers to develop plans that are realistic and achievable. Being too ambitious about what could be reasonably accomplished in a week often leads caregivers to become discouraged. Big problems take time and patience to resolve and so caregivers will be more likely to succeed if they step back and think long term about the problems they face.

Expert Information

Successful problem-solving often requires expert advice to help individuals better understand their problems and what the potential solutions might be. Caregivers are reminded that some people are experts because they have years of formal education and training (e.g. social workers, physicians, nurses, etc.). Others are experts because they have jobs where they spend all day assisting people who share similar problems. Still others are experts because they themselves have been dealing with a problem for a long time and have become very good at knowing what strategies do and do not work. Joe would be guided to think about and list people who could offer him facts about the problems he is facing and even include this exercise as a strategy to start addressing his problems.

Step 1: Identify & Describe the Problem

After orienting caregivers to the COPE attitude, caregivers are asked if they have a particular problem they are facing that they want to address. If so, they identify and thoroughly describe a problem they are facing. For a caregiver like Joe, there are countless ways he might describe his various problems and so this step is well worth investing the time to discuss and think carefully through. When going through this step, there are several key points to keep in mind to help individuals frame the problem in a way that is actionable.

First, it is important to have caregivers be very specific about the problem they are dealing with. When a problem is stated too vaguely, it is difficult to figure out what the problem’s exact cause is and what might be done to help solve it. If Joe states “I don’t have enough time in my day,” he would be asked to be more specific. A more specific way to state his problem might be “I spend at least an hour each day of the week commuting back and forth to my mother’s house.”

Second, it is helpful if individuals think of their problems objectively. Caregivers are asked to think about what aspects of their problem can be seen, observed, or counted. Problems framed about how individuals feel can be hard to define objectively. For example, Joe might say “I feel so tired in the morning.” A more objective way for him to say this might be: “After falling asleep rather easily, I wake up 3 to 4 times each night worrying about everything I have to do the next day.”

Third, caregivers are instructed to frame problems in a way that gives them some control over their situation. Joe might say “My wife never says anything nice to me” or “My mother never wants to talk about what we should do if she can’t make decisions for herself.” Stating the problem in this way makes it difficult to readily think of things that might offer solutions and mitigate the problem. Joe would be coached to restate these problems in a way that gives him some control: “There are more positive ways my wife and I could communicate when I come home from my mother’s house each day” and “There are several things I would like to discuss the future medical care my mother wishes to receive with her directly”.

Fourth, caregivers are prompted to think of their problems in terms of what, when, where, how, why, and who. What happens that makes this a problem? When does the problem happen? Where does it happen? How does the problem happen? Who does the problem involve? What have you already tried to try to solve the problem? To help answer these questions, caregivers can be asked to imagine they are watching a video of their problem happen.

Step 2: Define and Set Goals

After a description of the problem has been thoroughly reflected upon and written down, the next step is to create a goal. The goal is what one plans to accomplish to help address the problem. Like the previous step, there are several points to keep in mind about the goal.

First, the goal should be action oriented. A caregiver’s goal should be some form of action they will perform. It is helpful in this step if caregivers begin their goal statements with “I will…”. The following statements lack an action orientation: “My relationship with my wife will get better” or “My financial outlook will improve.” In contrast, action statements are desired that help caregivers have more control: “I will do something kind for my wife each day” or “I will engage in at least one activity each week to help keep our finances healthy.”

Second, the goal should be achievable within a short time frame, such as one week. If Joe stated: “My goal is to stop being angry” or “I will sleep for 8 hours every night this week”, he would be asked if he really thought this was something that was achievable in the next week. More achievable goals for Joe might be phrased: “I will employ three strategies this week to help me deal with my anger” or “I will use two sleep hygiene techniques each night to help me sleep better.”

Third, it can be helpful if the goal is general. It is helpful if Joe frames his goal in a way such that multiple options or alternatives could be proposed to meet the goal. Instead of “I will ride my bicycle 2 times this week”, Joe would be coached to restate the problem as “I will do two things this week to exercise”. This will give Joe the opportunity to think of many different options to meet his goal besides riding his bicycle.

Fourth, make the goal objective. This means a caregiver should make the goal measurable, so that he or she knows when they have been successful. Joe might first think of a goal that lacks objectivity: “I’m going to stop worrying about the future.” The issue with framing the goal in this way is that it becomes difficult to know when it has been accomplished. It can be more helpful if Joe considers alternative ways of stating his goal such as: “I’m going to engage in two activities each week to help me reduce my concerns about the future.”

Step 3: Brainstorm Options

In this step, caregivers brainstorm as many possible options as they can to help meet their goal. They are reminded that this is where creativity is really important and to resist judging for the moment how realistic particular options are. To help individuals generate different options, they are advised to think about what they could change about themselves, their environment, or the way they do an activity. Examples of changing something about oneself include: using a thought-stopping technique when negative thoughts arise; increasing one’s knowledge of community resources to help with providing daily care; and reading an inspirational book. Examples of changing something about one’s environment include: rearranging kitchen workspaces so that the care recipient can more easily get to frequently used items; moving the television out of the bedroom to help promote better sleep; and preparing a private space in the home one can retreat to in moments when one feels they are on the verge of saying angry things to another person. Examples of changing the way one does things might include: delegating daily tasks to family members or friends; cooking food in larger amounts so that there are leftovers; and keeping a family calendar to help organize everyone’s activities.

Two final points about this step: first, caregivers are strongly cautioned against generating options that involve changing the feelings, attitudes, or behaviors of other people. This is typically out of a person’s control. Second, as recommended in problem-solving treatment (Hegel et al., 2004; Unützer et al., 2002), one should resist the urge to offer options and advice to the caregiver. The reason is so that caregivers can enhance their problem-solving skills which can be used for any current or future problems and not just a particular problem at hand. Being able to independently generate options is part of those skills. Moreover, participants have a tendency to “shoot down” options when they originate from others unless they specifically ask for advice. This can be a difficult step for practitioners who are often trained to “give advice.” Though there may be times that providing advice may be appropriate, it is limited in this context when trying to enhance a person’s skills in problem-solving.

Step 4: Consider Pros and Cons of Each Option

At this point, a caregiver like Joe has identified several different options that might meet his goal. Each option has both advantages (i.e., “pros”) and disadvantages (i.e., “cons”). To determine the advantages of each option Joe is asked, “Compared to the other options you have listed, what makes this solution a good one?” For example, Joe’s goal might be to start a conversation with his mother about her end-of-life wishes. He has brainstormed three ways to start a conversation: (1) Visit an advance care planning website with his mother (like gowish.org or prepareforyourcare.org); (2) Read advance directive paperwork (e.g. living will) with his mother; or (3) watch a movie together that has end of life themes (e.g. The Descendants, Wit, Terms of Endearment, My Life). Joe feels the first option would give him concrete guidance and a structure to follow that might make the conversation easier. The second option seems to be the most efficient use of time, because he could actually complete the necessary paperwork during the conversation. Joe feels the third option would be most appealing to his mother (who loves films) and might stimulate a deeper and more meaningful conversation.

After listing the advantages of each option, caregivers are asked to consider the drawbacks to each option. Specifically, Joe needs to determine the degree to which time, effort, money, negative feelings, or the need for cooperation from the physical or social environment would make the solution hard to implement (see Table 3). Using the example above, Joe might report that while he would like using a website, he would need to bring his mother to his house or to a public place because she does not have a tablet or internet service at her house. As such, it might be hard to have a candid conversation if other people are around. Regarding the second option, Joe finds the advance care directive paperwork to be slightly dry and hard to understand. His mother threw the paperwork away on two occasions and bristles when Joe mentions the need to complete it. Finally, while Joe thinks the last option has the best chance of getting the outcome he wants (i.e., understanding his mother’s wishes and priorities for her care), he notes that it will take a lot of time and his wife may be annoyed that he has to spend even more time with his mother.

Table 3.

ENABLE Steps and Principles in Problem-Solving Support

| Key Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Introduction: Orient the person to a positive problem-solving attitude |

|

|

| Step 1: Prompt the individual to define and describe the problem they are facing |

|

|

| Step 2: Define and set measurable and achievable goals |

|

|

| Step 3: Direct the caregiver to generate alternatives for addressing the problem |

|

|

| Step 4: Ask the individual to consider the pros and cons of each alternative |

|

|

| Step 5: After choosing an alternative, ask the person to create an action plan for the coming week |

|

|

| Step 6: Have the person assess and evaluate how their plan worked out over the past week |

|

|

During this step, it is important to remind Joe that all potential solutions have pros and cons. The goal is not to identify a “perfect” solution, but rather to think strategically about which solutions have the best chance of successfully solving the problem. In subsequent steps, Joe can make sure his action plan finds a way to maximize the “pros” and minimize the “cons” of the chosen solution.

Step 5: Choose the Best Option(s) & Create an Action Plan for the Coming Week

Next, Joe is directed to compare the pros and cons among each of the options he listed. Key points emphasized about picking the “best” option include feasibility and achievability. Feasibility means choosing the options for which one has resources (broadly defined) to carry out. Achievability means choosing options that one has the energy and motivation to accomplish.

After one or more options are selected, it is time to have Joe think about the coming week. Joe would be asked to write down clear, concrete steps to achieving his goal through the options he selected. Questions he might be asked include: What will you do this week? When and where will you do it? Who is going to help you? What things might get in the way and how will you handle these obstacles? The more specific Joe is with his plans, the better chance he has for success. Joe might be asked, “If your plan works out this week, then great! But if it does not, pay attention to what things got in the way and we’ll talk about them next time we speak.”

Anticipating the barriers that may arise that could thwart plans for the coming week highlights the importance of having Joe generate a “Plan B” as part of his action plan. Joe would be prompted to refer back to the problem definition step and asked to identify predictable barriers based on how he framed the problem. He would then discuss what he will do if he encounters these barriers. Having a Plan B in mind helps caregivers like Joe minimize the chances that action plans will be completely abandoned once the first sign of trouble arises (as it often will).

Step 6: Assess & Evaluate the Action Plan

It is critical to check in with caregivers on their progress from week to week if possible. Joe might be asked on subsequent encounters: “Were you able to achieve what you set out to do when we last talked?” Many plans do not work out the first time and it is important to tell caregivers this is okay. Maybe an obstacle came up that they did not expect. Maybe the goal was too ambitious. Or maybe the caregiver was lacking in motivation. Have caregivers review what things got in the way of them implementing their plan. Ask them what they are going to do in the coming week to try and overcome these obstacles.

Case Study Outcome

After becoming familiar with Joe’s background and circumstances leading up to his not sleeping well and feeling overwhelmed with caring for his mother Susan, you decided to provide problem-solving support. You first introduced him to the COPE attitude, especially emphasizing optimism, that helped Joe realize that he was practicing a negative problem orientation by trying to avoid his problems by not thinking about them and “toughing it out.” You then discussed with Joe the key principles of the first step in problem-solving, defining and describing the problem (see Table 3). Joe found this step motivating because it helped him see how his problems could be viewed differently depending on different angles one could choose to take on the situation. As you and Joe discussed how to define a clear problem, you noticed he kept talking about changing his wife Ann’s behavior. You explained to Joe that we cannot control or change others and the problem needed to be about something he could influence. Joe chose to focus on his own feelings and thoughts and the trouble he had in managing them, particularly when he was trying to sleep. The problem Joe defined was: “I have difficulty managing distressing thoughts and emotions when I’m trying to sleep at night” (see Figure 1). To address this problem, Joe said his goal was to sleep better at night; but you reminded him that his goal needed to be action-oriented and measurable. He restated his goal to be: “I will perform 1 to 2 things each evening before I go to bed to help me sleep better.” You then asked Joe to brainstorm options to meet this goal. At first, Joe was intimidated and felt embarrassed about coming up with options that he did not think were very good. You reminded Joe to withhold judging options and to just think of as many ideas as possible. Joe was able to come up with several options, which he listed on his worksheet (Figure 1). After thinking about the pros and cons of each option, Joe decided to select avoiding caffeine after 3pm and to exercise 20 minutes a day. You then asked him what his action plan was going to be for the coming week. He said he was going to set a daily alarm on his phone to remind him to stop drinking coffee and soda after 3pm. For exercise, he planned to ride his bike along a 4 mile route he used to do regularly in his neighborhood when he got home in the evening. You prompted him about a ‘Plan B’ just in case his plans did not work out, but he insisted he could do these two things and that nothing was going to get in the way. You saw Joe a couple of weeks later and ask him how it his plan was going. He tells you things have improved. He has limited his caffeine after 3pm; however exercising has been more of a challenge due to the rainy weather the past few weeks. You asked him what his plan was to overcome this obstacle and he said he planned on using his stationary bike in the garage on those days. You expressed looking forward to seeing how it goes the next time you see him.

The Use of Problem-Solving Support by Social Workers

There is emerging evidence that problem-solving support has the potential to be incorporated into day-to-day social work practice in palliative and hospice care. Successful use of problem-solving support by social workers has been demonstrated in various populations including advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers (Bevans et al., 2014; Bucher et al., 2001), older dialysis patients (Erdley et al., 2014) and depressed, homebound elders (Choi, Wilson, Sirrianni, Marinucci, & Hegel, 2014). In these studies, social workers feasibly and effectively delivered problem-solving support in sessions ranging from 60 to 90 minutes to both family caregivers and patients. There is currently an ongoing multisite implementation trial funded by the American Cancer Society to implement ENABLE as a standard of care in community-based cancer centers. From this trial, it has been observed that social workers practicing in the palliative and hospice setting already use or can readily acquire formal problem-solving support skills. Hence, social workers who incorporate the specific steps of problem-solving support, are not learning a new skill, but rather honing tactics that are already part of their current toolbox. Some limitations and challenges social workers may have in attempting to use problem-solving support include having the space and time necessary to sit down one-on-one with individuals for up to 90 minutes to go through the steps (Bucher et al., 2001). It may also be difficult to reliably schedule follow-up with individuals over time to help them evaluate what progress and challenges they are having in reaching their goals. While a number of different problem-solving trials in a variety of settings have undergone testing (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 2007; Kirkham, Choi, & Seitz, 2015), future research could continue to fill the gap in what is known about the feasibility and effectiveness of problem-solving support delivered specifically by social workers.

Conclusion

Formal problem-solving therapy approaches and techniques have been developed over the past several decades to assist individuals at becoming better at managing the problems they face. Principles and techniques from these developments were incorporated into ENABLE (Educate Nurture Advise Before Life Ends), an intervention for persons with advanced cancer and their primary family caregivers. A vast literature reports that family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer take on numerous responsibilities and tasks that invariably present daunting and complex problems (Bee et al., 2008; Stenberg et al., 2010). Serious problems that go unresolved can burden caregivers and result in negative outcomes to their psychological and physical health and can potentially impact the quality of care they deliver to their care recipients with cancer. Using a case-based approach, this article aimed to present an overview of key principles, techniques and steps in problem-solving coping that we have used in ENABLE. Though more research is needed to formally test the use of problem-solving support in social work practice, social workers are well primed to incorporate the steps and techniques described in this article into their everyday practice.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Dionne-Odom JN, Ahles TA. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee P, Barnes P, Luker K. A systematic review of informal caregivers’ need in providing home-based end-of-life care to people with cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;18:1379–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Castro K, Prince P, Shelburne N, Soeken K, Wallen GR. A problem-solving education intervention in caregivers and patients during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(5):602–617. doi: 10.1177/1359105313475902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher J, Loscalzo M, Zabora J, Houts P, Hooker C, BrintzenhofeSzoc K. Problem-solving cancer care education for patients and caregivers. Cancer Pract. 2001;9(2):66–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009002066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher J, Zabora J. Building Problem-Solving Skills through COPE Education of Family Caregivers. In: Holland J, Breitbart W, Jacobsen P, Lederberg M, Loscalzo M, McCorkle R, editors. Psycho-Oncology. Second. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher JA, Loscalzo M, Zabora J, Houts PS, Hooker C, BrintzenhofeSzoc K. Problem-solving cancer care education for patients and caregivers. Cancer Pract. 2001;9(2):66–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009002066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assuring Health Caregivers. Neenah, WI: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Wilson NL, Sirrianni L, Marinucci ML, Hegel MT. Acceptance of home-based telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults: qualitative interviews with the participants and aging-service case managers. Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):704–713. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla T, Nezu A. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Positive Approach to Clinical Intervention. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Tosteson T, Li Z, Bakitas MA. Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: Outcomes From the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdley SD, Gellis ZD, Bogner HA, Kass DS, Green JA, Perkins RM. Problem-solving therapy to improve depression scores among older hemodialysis patients: a pilot randomized trial. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82(1):26–33. doi: 10.5414/CN108196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evercare and National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregivers in Decline: A Close-up Look at the Health Risks of Caring for a Loved One. Bethesda, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel MT, Dietrich AJ, Seville JL, Jordan CB. Training residents in problem-solving treatment of depression: a pilot feasibility and impact study. Fam Med. 2004;36(3):204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson PL, Thomas K, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D. Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):522–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Delivering High Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington DC: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham JG, Choi N, Seitz DP. Meta-analysis of problem solving therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1002/gps.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Loscalzo M, Bucher J. The COPE Model: Its Clinical Usefulness in Solving Pain-Related Problems. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1999;9(2):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KD, Bakitas M, Hegel MT, Hanscom B, Hull J, Ahles TA. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Palliative care (FACIT-Pal) scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.015. doi: S0885-3924(08)00217-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney C, Lyons KD, Li Z, Hegel M, Ahles TA, Bakitas M. Patient perspectives on participation in the ENABLE II randomized controlled trial of a concurrent oncology palliative care intervention: benefits and burdens. Palliat Med. 2013;27(4):375–383. doi: 10.1177/0269216312445188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan S, Small B. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice homecare patients: a clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):313–321. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan S, Small B, Weitzner M, Schonwetter R, Tittle M, Moody L, Haley W. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer. 2005;106(1):214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice homecare patients: a clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):313–321. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, Schonwetter R, Tittle M, Moody L, Haley WE. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer. 2005;106(1):214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Liao KP, Anderson KO, Garcia-Gonzalez A, Hahn K, Cleeland CS. Caregiver symptom burden: the risk of caring for an underserved patient with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(5):1070–1079. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SM, Kim YJ, Kim S, Choi JS, Lim HY, Choi YS, Yun YH. Impact of caregivers’ unmet needs for supportive care on quality of terminal cancer care delivered and caregiver’s workforce performance. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(6):699–706. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins M, Howard VJ, Wadley VG, Crowe M, Safford MM, Haley WE, Roth DL. Caregiving strain and all-cause mortality: evidence from the REGARDS study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):504–512. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):P126–137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):493–497. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalla K, Bakitas M, Furstenberg C, Ahles T, Henderson J. Patients’ need for information about cancer therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(2):313–320. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(10):1013–1025. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K, Hudson P, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D. Risk factors for developing prolonged grief during bereavement in family carers of cancer patients in palliative care: a longitudinal study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(3):531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Treatment, I. I. I. M.-P. A. t. C Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(5):336–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4362–4373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]