Abstract

The formation of atherosclerotic plaques in the large and medium sized arteries is classically driven by systemic factors, such as elevated cholesterol and blood pressure. However, work over the past several decades has established that atherosclerotic plaque development involves a complex coordination of both systemic and local cues that ultimately determine where plaques form and how plaques progress. While current therapeutics for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease primarily target the systemic risk factors, a large array of studies suggest that the local microenvironment, including arterial mechanics, matrix remodeling, and lipid deposition, plays a vital role in regulating the local susceptibility to plaque development through the regulation of vascular cell function. Additionally, these microenvironmental stimuli are capable of tuning other aspects of the microenvironment through collective adaptation. In this review, we will discuss the components of the arterial microenvironment, how these components crosstalk to shape the local microenvironment, and the effect of microenvironmental stimuli on vascular cell function during atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, microenvironment, shear stress, extracellular matrix, inflammation

A. Introduction to Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis, a lipid-driven chronic inflammatory disease of large and medium sized arteries, which hinders arterial function and prevents adequate blood flow to target tissues. Lipid deposition in the arterial wall drives the influx of macrophages to clear the lipid deposits, but continued elevations in plasma cholesterol and inefficient clearance results in extracellular lipid pools and macrophage necrosis driving the formation of a necrotic core [1]. This intimal inflammatory response activates smooth muscle cells in the underlying medial layer to change phenotype and migrate into the neointima [2]. Smooth muscle cells contribute to plaque size and lumen occlusion through fibroproliferative remodeling. However, this fibroproliferative response also results in the formation of a smooth muscle- and collagen-rich fibrous cap that provides the plaque with mechanical stability and prevents plaque rupture, the primary cause of thrombotic complications and atherosclerosis-related mortality [3].

Over the past several decades advances in molecular and cellular tools and novel animal models of atherosclerotic disease significantly enhanced our understanding of atherosclerotic plaque development and progression. Multiple atherosclerotic risk factors have been identified, including age, family history, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and lifestyle (ex. physical inactivity, smoking) [1]. However, it is now clear that atherosclerotic plaque formation is a function of both systemic atherogenic risk factors and the local arterial microenvironment. Multiple components of the arterial microenvironment contribute to plaque formation, including vessel mechanics, matrix composition, and local production and deposition of soluble factors that perpetuate atherogenic inflammation (Figure 1). Hemodynamics play a vital role in regulating local susceptibility to plaque formation through effects on endothelial cell function [4]. Remodeling of the vessel matrix regulates lipid deposition and endothelial cell activation, as well as leukocyte and smooth muscle function. Additionally, cyclic stretch and stiffening of the vascular matrix alters cellular function through applied mechanical load on the vessel wall [5]. Despite these critical roles of microenvironmental stimuli, existing therapeutics only target systemic factors, such as lowering of circulating cholesterol, reducing blood pressure, and preventing thrombotic complications. Although these have shown remarkable success in reducing cardiovascular events, the residual risk for cardiovascular disease remains high. Through a better understanding of the local microenvironmental stimuli that drive site-specific plaque formation, novel therapeutics may be developed to reduce the residual risk.

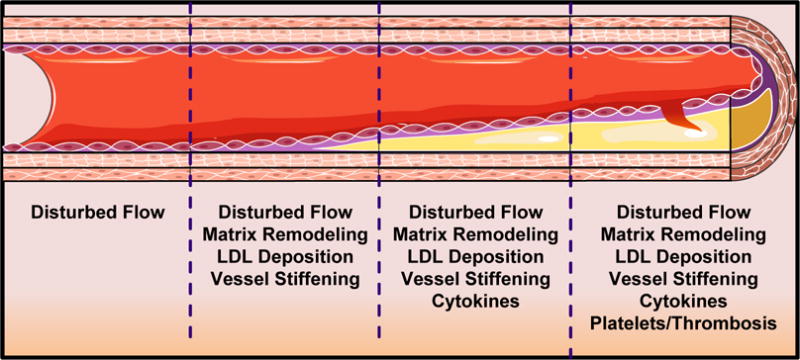

Figure 1. Microenvironmental Influence on Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation.

Changes in the microenvironmental stimuli as vessels progress from early atherogenesis to clinically relevant atherosclerotic plaques.

B. The Arterial Microenvironment in Atherosclerosis

1. The Arterial Extracellular Matrix

The extracellular matrix, a complex organization of collagens, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins, confer physical properties such as rigidity, porosity, and topography to the various tissues of our body [6]. In addition, matrix proteins contain cell-binding motifs that allow cells to adhere, organize, and respond to changes in the extracellular matrix. The matrix functions also as a selective reservoir for soluble factors that provide cues to control cell phenotype. While matrix composition and structure modulate cell function, cells actively remodel the matrix [7]. Controlled matrix remodeling during development facilitates organ morphogenesis and wound healing, whereas uncontrolled remodeling causes tissue fibrosis, interrupts tissue function, and perpetuates chronic inflammatory diseases [8].

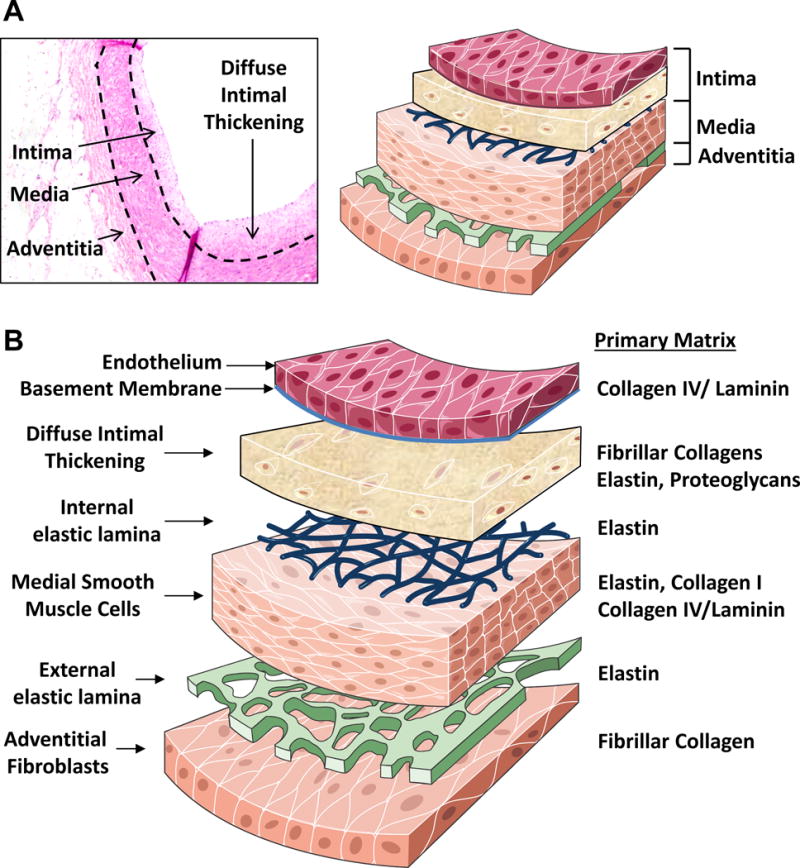

Extracellular matrix composition differs significantly between the arterial layers. Endothelial cells normally reside on a basement membrane, an elaborate, thin layer of collagen IV, laminin-8/10, nidogen, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (Figure 2) [9]. The smooth muscle-rich medial layer consists primarily of elastin fibers which provide elasticity to the vessel and fibrillar type I and type III collagens that provide tensile strength. Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) interact with both fibrillar collagens and a thin collagen IV/laminin-rich basal laminae that covers much of the smooth muscle surface [10]. In the plaque neointima, matrix composition changes considerably (Figure 2). Diffuse intimal thickening, apparent within the first few decades of life, precedes atherosclerotic plaque development and consists of nonproliferative SMCs, proteoglycans, and elastin fibers [11]. The endothelial basement membrane undergoes remodeling to include provisional matrix proteins typically associated with wound healing, such as fibronectin and fibrinogen [12]. The internal elastic laminae, a barrier for smooth muscle recruitment from the media, is degraded by elastases produced by invading macrophages and activated SMCs [13]. The neointimal SMCs produce a bulk of the atherosclerotic matrix, primarily involving collagen synthesis with nearly 60% of total plaque protein consisting of type I collagen.

Figure 2. Vascular Matrix by Arterial Layer.

A. Depiction of the arterial intima, media, and adventitia in a human coronary artery. Dashed lines represent the internal and external elastic lamina. B. Changes in the primary vascular matrix components in the different arterial layers.

The most prominent extracellular matrix receptors belong to the integrin family, encompassing 18 α and 8 β subunits that heterodimerize into 24 distinct integrins with both shared and specific, non-redundant functions [14]. While integrins do not contain enzymatic activity, they recruit a vast array of signaling proteins to form a localized signaling hub at the cell-matrix interface. Activation of disparate signaling responses, through integrin-specific recruitment of certain signaling partners, generates contextual cues that affect cell function and integrate with other microenvironmental stimuli [15]. Arterial endothelial cells interact with collagen IV and laminins through the integrins α2β1, α3β1, α6β1, and α6β4 [16]. SMCs interact with their matrix through the collagen-binding integrins α1β1 and α2β1 and the laminin-binding integrins α3β1 and α7β1, although other non-integrin receptors also mediate this interaction including the collagen-binding discoidin domain receptors (DDRs) and the laminin-binding receptor α-dystroglycan [17]. In contrast, the provisional matrix proteins deposited during atherosclerotic plaque development typically bind to integrins that interact with the classic RGD integrin-binding motif, including α5β1, αvβ3, and αvβ5 [15]. While collagen and laminin-binding integrins are generally associated with cellular quiescence, provisional matrix-binding integrins typically promote cell migration, proliferation, and survival during tissue remodeling [15].

2. Arterial Mechanics

Cyclical cardiac output created from the contracting heart drives perpetual tangential shear stress due to the flow of viscous blood across the endothelium and circumferential stretch that distends the vessel wall. While these forces are largely governed by vessel geometry, changes in vessel stiffness or peripheral resistance can significantly affect the forces applied to the large arteries. Atherosclerotic plaques form preferentially at vessel branchpoints, curvatures, and bifurcations exposed to disturbed flow patterns characterized by flow separation, changes in flow direction, and recirculation eddies (Figure 3) [4, 18]. Even under pathological conditions that promote atherosclerosis, regions of the vasculature exposed to unidirectional laminar flow show resistance to plaque formation [4]. Endothelial cells sense the shear stress generated by these flow patterns through specialized mechanosensors that convert the shear stress stimulus into intracellular biochemical signals, a process termed mechanotransduction [4, 18]. Mechanosensors proposed to mediate the endothelial response to shear stress, including the endothelial glycocalyx, G protein coupled receptors, ion channels, adherens junctions, and integrin-mediated cell-matrix adhesions, have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [19, 20]. We will instead focus our discussion on the regulation of endothelial cell function by arterial mechanics.

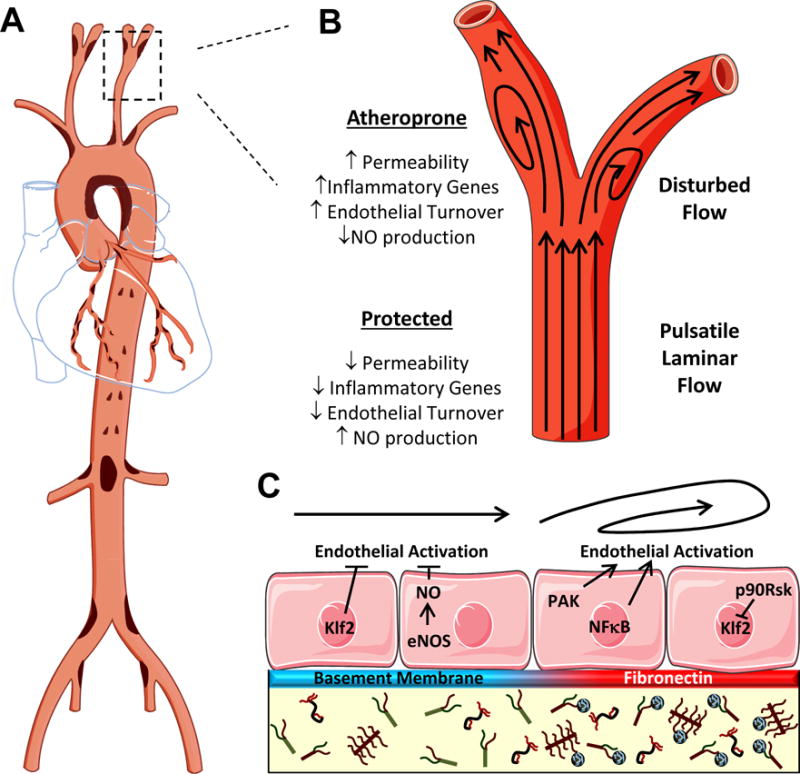

Figure 3. Mechanics and Matrix in Endothelial Activation.

A. Schematic for the prevalence of atherosclerotic plaque formation throughout the arterial tree. Plaque-prone areas are indicated in brown. B. Association of different flow patterns with a protected or atheroprone endothelial cell phenotype. C. Mechanisms of differential endothelial activation due to changes in flow patterns and subendothelial matrix composition.

Due to differences in the mechanical properties of the individual arterial layers, the media resists a majority of the circumferential stretch (~60%), while the adventitia resists 40% of circumferential stretch and ~75% of longitudinal stretch [21]. SMCs in the media align their actin cytoskeleton parallel with the axis of stretch resisting mechanical deformation [22]. At low arterial pressure, elastin fibers absorb much of the circumferential stretch forces, whereas rigid collagen fibers resist mechanical deformation to high circumferential stretch resulting in elevated strain applied to the smooth muscle layer. Since tissue stretch is transmitted through deformation of the extracellular matrix, sites of cell-matrix adhesion play a primary role in sensing changes in vessel stretch [18].

3. Cholesterol and Inflammation

Cholesterol deposition in the arterial wall promotes a chronic inflammatory response resulting in leukocyte recruitment into the vessel wall. Apoliprotein-B containing lipoproteins, such as low density lipoproteins (LDLs), carry cholesterol throughout the body. During hypercholesterolemia, LDL transverses the endothelium and becomes deposited into the arterial intima. Genetic mouse models that enhance circulating LDL levels, such as the LDL receptor (LDLR) knockout mouse and the ApoE knockout mouse, promote both hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerotic plaque formation [23]. If not promptly cleared, LDLs can become oxidized by various enzymes, such as sphingomylenase C, lipoxygenases, myeloid peroxidases, and secretory phospholipase A2 forming oxidized LDLs (oxLDLs) [24]. OxLDL elicits endothelial cell expression of cell adhesion molecules and chemokines that recruit inflammatory cells into the arterial intima [24, 25]. Although many chemokines have been implicated in atherogenesis, three of the most prominent chemokine:chemokine receptors involved with atherosclerosis include macrophage chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2):CCR2, fractalkine (CX3CL1):CX3CR1, and RANTES (CCL5):CCR5. The loss of any of these chemokine or chemokine receptors in mice ablates atherosclerotic progression [26]. We will briefly discuss the in vivo nature of modified LDLs, but if readers are interested we would refer them to an excellent review by Levitan et. Al [27], for more comprehensive review of oxidized LDLs. Furthermore, we recognize there are a variety of techniques to generate numerous different species of modified LDLs such as acetylated (AcLDL), minimally modified (mmLDL), heavily oxidize and aggregated to recapitulate the in vivo nature of oxLDL. These different modification can at times have differing effects on cellular responses in vitro, if there are noted differences to different modification to LDL we will make special not of that (i.e. mmLDL, acLDL, or oxLDL), if however, responses are generalized to all types of oxLDLs we will refer to these as mod-LDLs.

There is strong support for oxidation of LDLs taking place in vivo as they are present in human and mouse atherosclerotic lesions. However, the natural composition of oxLDL, as well as, the mechanisms that drive in vivo oxidation are still largely enigmatic. Although, oxidized LDLs have been identified in the serum, the majority of modification of LDLs likely takes place in arterial intima, where LDLs can be sequestered by proteoglycans [28]. The modification/oxidation of LDLs is likely a combination of enzymatic (i.e. lipoxygenases) and oxidizing (i.e. nitrogen free radicals) activity. Monitoring the formation of 13-hydroxy- 9Z, 11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-HODE) does give some insight into the potential stages of LDL modification during the course of atherosclerosis. 15-lipoxygenase and transition metals can modify components of LDLs to generate 13-HODEs; however, 15-lipoxygenase results in the formation of S isomers while oxidation results in R isomers [29]. Early stage plaques show a high 13-HODE S/R ratio whereas late stages of plaques show a balanced ratio [30], suggesting early modification of LDLs in the plaque may be enzymatically driven while later modification may be driven by oxidative/free radical processes.

As the plaque progresses, a staggering array of immune cells migrate into the plaque and release a variety of cytokines that contribute to plaque progression or plaque regression. Cytokine responses within a plaque can be divided along lines well established within the immunologic field. Cytokines associated with inflammatory macrophage and Th1 T cell responses, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) promote atherosclerosis [31]. In contrast, cytokine produced by wound healing macrophages and Tregs, such as IL-13, IL-10, IL-19, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) reduce atherosclerosis [31]. Pro-atherogenic cytokines enhance foam cell formation by enhancing modified LDL uptake and inhibiting proper reverse cholesterol transport in macrophages. TNF-α and IFN-γ also enhance macrophage and smooth muscle cell apoptosis, which contribute to growth of the necrotic core and thinning of the protective fibrous cap. In addition to the elicitation of pro-inflammatory immune responses, modLDLs can induced apoptosis and/or necrosis that may contribute to the formation of the necrotic core. Necrotic core progression is likely due to the formation of cholesterol crystals in the cytosols leading to inflammasome activation and subsequent IL-1α/β production [32]. In addition M1 macrophages can contribute to oxidative stress observed in the plaque via the production of hydrogen peroxide, superoxides, neopterin (the oxidized product of 7, 8-dihydroneopterin) and myeloperoxidases [33, 34]. These radicals can promote further oxidation of LDLs within the plaques, as well as the initiate of endoplasmic reticulum stress that can initiate apoptosis.

In addition to atherogenic inflammatory responses

the atheroprotective cytokines IL-10, IL-19, and TGF-β reduce leukocyte recruitment and inflammation [31, 35, 36]. The balance between pro-atherogenic cytokines and anti-atherogenic cytokines likely dictates the rate in which atherosclerosis progresses. In addition, to anti-inflammatory cytokines, various anti-oxidants can also be produced in the plaque, including tocopherol and 7,8-dihydroneopterin [37]. These antioxidants can protect both LDLs from oxidation, as well as macrophages from oxidant induced cell death [38]. Within advanced plaques significant levels of oxidants, antioxidants, pro-inflammatory cytokine responses and anti-inflammatory cytokines responses can be measure. This makes the plaque a dynamic environment in which the combination of pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidants production can promote plaque progression, instability and rupture.

C. The Arterial Microenvironmental and Endothelial Activation

The endothelium plays a multifaceted protective role in maintaining vessel quiescence by regulating vasodilation to minimize mechanical damage, limiting vascular permeability, and preventing the interaction of platelets and leukocytes to the vessel wall [39]. Early during atherogenesis, multiple environmental factors cause the endothelium to lose its protective functions resulting in a leaky, proinflammatory surface, a process termed endothelial activation [39]. Classic endothelial activators, including cytokines (ex. TNF-α, IL-1β), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and oxLDL [39, 40], stimulate the proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-кB (NF-кB) to drive the mRNA expression of leukocyte-binding cell adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), E-selectin), chemokines (MCP-1), and the potent smooth muscle mitogen platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) [40]. In contrast to endothelial activation, the term endothelial dysfunction typically refers to the loss of vasodilatory capacity of the endothelium, primarily due to a deficiency in nitric oxide (NO) production [41]. Since the large elastic arteries prone to atherosclerosis show limited vasodilatory capacity, the association between endothelial dysfunction in the peripheral vasculature and atherosclerosis likely involves the loss of NO’s numerous protective properties in the atherosclerotic endothelium, such as its ability to reduce NF-кB activation, prevent platelet and leukocyte adhesion, and limit smooth muscle proliferation [41].

1. Shear Stress and the Endothelium

Blood flow patterns play a dominant role in regulating endothelial activation. In regions of unidirectional laminar flow, endothelial cells exhibit a quiescent phenotype associated with elevated NO production, reduced oxidant stress, low endothelial turnover, enhanced barrier function, and limited proinflammatory gene expression (Figure 3B) [4]. In contrast, vascular regions exposed to disturbed flow show enhanced endothelial activation characterized by reduced NO production and enhanced oxidant stress, endothelial turnover, permeability, and proinflammatory activation. Prolonged exposure to laminar flow in culture actively suppresses endothelial activation by cytokines, LPS, and oxLDL by hindering NF-кB-dependent proinflammatory gene expression and promoting NF-кB-dependent anti-apoptotic gene expression [42, 43]. Flow-induced protection involves multiple pathways; however the activation of Erk5/kruppel-like factor 2 (Klf2) and NO production appear to play particularly important roles (Figure 3C). Endothelial cells exposed to laminar flow show robust Erk5-dependent expression of Klf2, which binds NF-κB directly and competes for binding of transcriptional coactivators [44]. Elevated NO production by laminar flow similarly reduces endothelial proinflammatory gene expression in response to TNF-α, LPS, and oxLDL [43]. In addition to these, cellular alignment and elongation with laminar flow limits local mechanical stress and reduces endothelial inflammation. The cell surface proteoglycan syndecan-4 is required for both endothelial alignment with flow and protective anti-inflammatory signaling by laminar flow [45]. Interestingly, syndecan-4 knockout mice show enhanced atherosclerosis at typically protected sites, suggesting a critical role for syndecan-4 in mediating laminar flow-induced atheroprotection [45]. However, these studies utilized global syndecan-4 knockout mice rather than endothelial-specific deletion, suggesting that other cell types may contribute to this phenotype.

Shear stress regulates NO production through effects on both eNOS expression and activity. Laminar flow promotes endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) expression through Klf2 and NF-κB [46]. This NF-κB-dependent eNOS expression may regulate negative feedback on endothelial activation, with NF-кB promoting NO production which limits flow-induced NF-кB activation [46, 47]. Shear stress classically activates eNOS through transient calcium influx, resulting in calmodulin binding, and through eNOS phosphorylation following activation of the shear stress mechanosensor PECAM-1 and its downstream signaling partner Akt [48]. However, a growing body of evidence suggest that this model requires revision. Shear stress-induced nitric oxide production requires ATP release, activation of purinergic receptors (P2Y2, P2Y4), and Gq/11-dependent calcium influx [49–51]. Elevated intracellular calcium enhances cytoskeletal tension, and blunting P2Y2 or Gq/11 signaling prevents flow-induced PECAM-1 phosphorylation [51], suggesting that shear stress-induced PECAM-1 mechanotransduction may sense intracellular forces rather than extracellular shear forces. Uncoupling this pathway through endothelial-specific deletion of P2Y2 or Gq/11 in mice blunts flow-induced vasodilation and elevates blood pressure. Similarly, endothelial-specific deletion of the small GTPase Rap1 blunts flow-induced NO production and enhances blood pressure in mouse models as well [52]. While this response is postulated to be due to Rap1’s influence on endothelial adherens junction structure [52], PECAM-1 knockout mice do not show increased blood pressure [53]. Like Akt, activation of protein kinase A (PKA) also appears to contribute to flow-induced eNOS activation through Ser phosphorylation [47, 54]. However, the mechanisms regulating shear-induced PKA activation remain elusive. The enzymes ATP diphosphohydrolase (CD39) and ecto-5′-nucleotidease (CD73) degrade ATP to form adenosine, and adenosine can stimulate PKA activation through its A2A and A2B receptors [55]. Laminar flow enhances endothelial CD39 and CD73 expression [56, 57], and deletion of either CD39 or CD73 enhances atherosclerosis in mouse models [56, 58]. Therefore, shear-induced ATP release may regulate NO production through multiple mechanisms.

Vascular regions exposed to disturbed flow show enhanced NF-кB activation and NF-кB subunit expression, and oscillatory flow, a model of disturbed flow, promotes NF-кB activation in cell culture models [40, 59]. Whereas disturbed flow induces NF-кB expression through the c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway [60], disturbed flow activates NF-кB through the enhanced production of reactive oxygen species and the activation of the serine/threonine kinase p21 activated kinase (PAK) [59]. PAK signaling appears to play a pivotal role in endothelial activation, as PAK also mediates disturbed flow-induced JNK activation and endothelial permeability [61, 62], shows enhanced activation in endothelial cells exposed to disturbed flow in vivo [61], is required for JNK activation, NF-кB activation, and vascular permeability at sites of disturbed flow in vivo [59, 61, 62]. To alleviate the anti-inflammatory expression of Klf2, disturbed flow also limits Erk5 signaling through its SUMOylation and inhibitory phosphorylation by p90 ribosomal S6-kinase (Figure 3C) [63, 64]. Additionally, oscillatory flow activates the endothelial inflammasome, a protein complex that functions to induce caspase-1-dependent activation of IL-1β [65]. The mechanisms regulating inflammasome activation by disturbed flow remain relatively unknown, but several studies suggest that flow-induced oxidative stress and activation of sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SREBP2) facilitates inflammasome activation [66, 67]. Inflammasome activation significantly contributes to atherosclerotic plaque formation, as deletion of caspase-1, IL-1β, or the IL-1 receptor all reduce atherosclerotic plaque formation [68–70]. As such, the IL-1β neutralizing antibody canakinumab is the subject of the first clinical trial to directly address the role of inflammation in atherosclerosis, the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS) trial. However, it remains to be tested whether the inflammasome contributes to endothelial proinflammatory responses in vivo directly or indirectly through macrophage-dependent IL-1β production.

In addition to inflammation, endothelial cells at atherosusceptible sites show signs of enhanced cellular injury as a result of mechanical, oxidative, and metabolic stress. Transcriptome analysis of endothelial cells at atherosusceptible sites suggest an important role of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in atherogenic endothelial activation [71]. ER stress occurs when protein rates overcome the ER’s ability to promote proper protein folding. The accumulation of misfolded peptides initiates the unfolded protein response, resulting in upregulation of ER chaperone proteins. Prolonged ER stress drives inflammation, oxidant stress, and apoptosis [72, 73]. Disturbed flow promotes ER stress in endothelial cells [74, 75], and mimicking ER stress enhances atherosclerotic plaque formation in laminar flow regions [75]. In contrast, laminar flow reduces endothelial cell metabolism through Klf2-dependent repression of endothelial glycolytic enzymes [76] and promotes endothelial cell autophagy to protect endothelial cells from oxidant-induced cell injury [77, 78]. In contrast, oscillatory flow stimulates a JNK-dependent increase in mitochondrial superoxide production [79] but limits autophagy, allowing the accumulation of oxidant injury and markers of DNA damage (8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine) at sites of disturbed flow [78, 80]. Enhanced oxidant stress at sites of disturbed flow correlates with increased endothelial cell apoptosis [81], and disturbed flow promotes SUMOylation-dependent nuclear export of the apoptosis-regulating transcription factor p53, resulting in Bcl2 binding and induction of endothelial apoptosis [82].

2. Matrix composition

Like disturbed flow, endothelial cell interactions with provisional matrix proteins critically regulate endothelial cell activation and permeability. Endothelial cells cultured on fibronectin show enhanced proinflammatory gene expression and increased permeability in response to shear stress and oxLDL [25, 59, 61]. Moreover, preventing fibronectin accumulation and assembly in mouse models of atherosclerosis blunts plaque progression and prevents vascular remodeling [83]. Both shear stress and oxidized LDL promote the activation of provisional matrix-binding integrins in endothelial cells, resulting in enhanced integrin-dependent signaling. Blocking signaling through α5β1 significantly reduces the oxLDL-induced NF-кB activation and proinflammatory gene expression, and α5β1 integrin inhibitors blunt early plaque formation in mice exposed to elevated plasma cholesterol [25]. Similarly, shear stress promotes the activation of both α5β1 and αvβ3 [84, 85]. However, only αvβ3 expression is required for shear stress-induced NF-кB activation and proinflammatory gene expression [16]. Like NF-кB, shear stress-induced PAK activation requires αvβ3 [16] and the presence of provisional matrix proteins [59, 61], and endothelial PAK activation corresponds to early fibronectin deposition at sites of disturbed flow in vivo [61]. In contrast, endothelial cells on basement membrane proteins show enhanced shear stress-induced PKA activation and NO production [47, 86], associated with reduced PKA-mediated eNOS phosphorylation [47]. Interestingly, enhanced NO production in endothelial cells on basement membrane proteins prevents shear stress-induced activation of PAK and NF-кB thereby limiting the proinflammatory response to shear [47, 86].

D. Microenvironmental Crosstalk in Leukocyte Function

Monocytes comprise approximately 5–10% of the circulating leukocyte pool yet substantially account for cells occupying atherosclerotic lesions. During early atherosclerosis, monocytes use PSGL-1 to tether to E-selection on activated endothelial cells facilitating rolling, and then adhere and transmigrate into the vessel wall using integrin LFA-1 (αLβ2) and VLA-4 (α4β1) interactions with their endothelial counter-ligands ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 respectively [87]. Subsequently, monocytes differentiate into macrophages and undergo polarization into M1, M2, or Mox subsets [26]. Importantly, the local tissue microenvironment critically regulates macrophage gene expression and function, tuning macrophage phenotype to tissue-specific demands [88]. Proatherogenic macrophages, usually the M1 subset, undergo maladaptive and non-resolving inflammatory responses that advance atherosclerosis. Continued secretion of proinflammatory mediators (cytokines and chemokines) and matrix-degrading proteases disrupt phagocytic clearance, or efferocytosis, and execute cell death through either secondary necrosis or apoptosis [26]. Lipids released by dying macrophages form the prothrombotic necrotic core, the distinguishing feature for unstable plaques. Although other leukocytes, such as dendritic cells and lymphocytes, play key roles during atherosclerosis, microenvironmental influence on macrophage function has received considerably more attention and will therefore be the focus our discussion.

1. Extracellular matrix activation of Macrophages

The unique extracellular matrix of atherosclerotic plaques significantly affects macrophage and foam cell function. Monocyte binding to collagen, the most abundant extracellular matrix component of the atherosclerotic plaque, induces monocyte to macrophage differentiation and markedly increases the phagocytic capacity of these cells such as the enhancement of modified LDL uptake [89]. Subsequent activation of these collagen-associated macrophages results in enhanced superoxide production and prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis [90]. Macrophages express the collagen receptor DDR1, and DDR1 deletion reduces plaque macrophage content, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity, and proinflammatory gene expression [91, 92], suggesting a major role for DDR1 in collagen-induced macrophage differentiation. Macrophages express multiple provisional matrix-binding integrins, including both α5β1 and αvβ3. Activation of α5β1 drives inflammasome activation, a protease complex responsible for IL-1β maturation, resulting in enhanced macrophage IL-1β production and proinflammatory responses [93]. In contrast, signaling through β3 integrins may reduce macrophage inflammation, as β3 deficient macrophages show enhanced TNF-α production and elevated atherosclerosis [94].

Extracellular matrix degradation can also produce cryptic peptides and soluble matrix fragments that further activate immune cells. Several soluble matrix fragments act as danger signals, also known as danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) [95], capable of binding to Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and activating NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory gene expression. For example, biglycan released from the extracellular matrix can activate TLRs and purinergic receptors resulting in activation of the inflammasome [96], and trangenic overexpression of biglycan in atherosclerosis-prone ApoE knockout mice enhances plaque formation [97]. Alternative splicing of cell-derived fibronectin can introduce an extradomain A (EDA) site, which activates macrophage TLR4 to induce the NF-кB-dependent gene expression [98]. Thus, changes in extracellular matrix observed within plaques likely regulate macrophage function, yet more research into this area is needed to delineate this contribution.

2. Mechanosignal transduction

While only a paucity of studies have examined macrophage regulation by biomechanical forces, several lines of evidence suggest that the biomechanical environment can affect macrophage function [99]. Substrate topography and matrix architecture, which are under constant flux in the atherosclerotic plaque, contribute to macrophage polarization [99]. Rough surfaces stimulate stronger macrophage adhesion and enhance the production of TNF-α, MCP-1, and MIP1- a upon stimulation with LPS [100], while an increase in substrate groove depth reduces cellular movement and enhances cellular phagocytosis [101]. In addition to matrix topography, stretching of the neointimal matrix may significantly affect macrophage differentiation. Physiological cyclic stretch increases the ratio of M2 to M1 macrophage differentiation in vitro; however elevated, pathological cyclic stretch reduces M2 macrophage differentiation while increasing M1 macrophage differentiation [102]. Together, these data suggest that normal physiological levels of stretch may enhance tissue repair or homeostasis while abnormal stretch, such as in hypertension, promotes inflammation [102]. Enhancing substrate stiffness, characteristic of atherosclerotic vessels, promotes macrophage adhesion and enhances phagocytosis [103, 104]. While these studies suggest that biomechanical forces can affect macrophage phenotype, no studies to date have examined the role of arterial biomechanics on macrophage function in the context of atherosclerosis.

E. The Arterial Microenvironmental and Smooth Muscle Phenotype

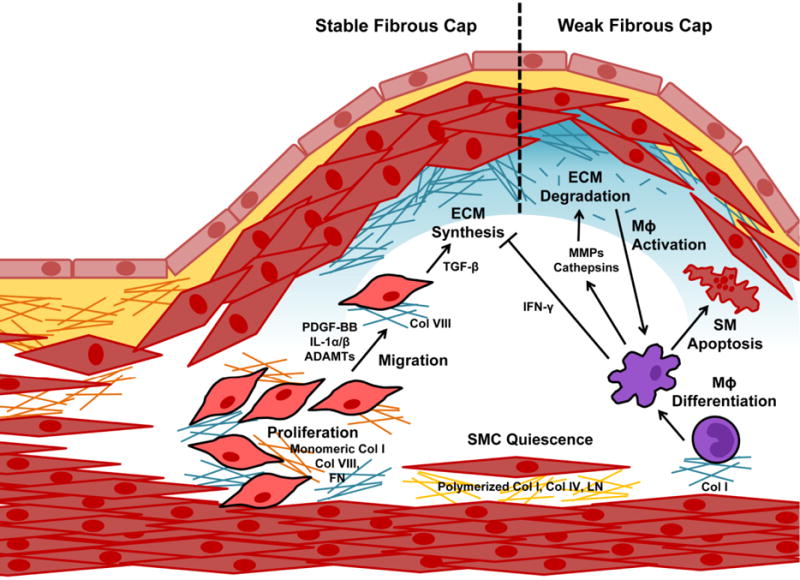

Vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) play a critical role in the progression of atherosclerosis. Traditionally known for their contractile modulation of blood flow and vessel tonicity, vascular SMCs undergo phenotypic dedifferentiation in response to diverse extracellular stimuli, including proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, oxidized LDL, and certain extracellular matrix proteins [2]. During this modulation from the contractile, quiescent phenotype to a synthetic, activated phenotype, SMCs decrease expression of contractile markers, become increasingly proliferative and migratory, and enhance their deposition of extracellular matrix proteins (Figure 4) [2]. Additionally, vascular SMCs express a number of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cell adhesion molecules that may contribute to local inflammation within the growing plaque [105]. Recent lineage tracking studies suggest that cells derived from SMCs actually contribute to a large percentage of the cells in the plaque staining positive for macrophage markers [106, 107]. However, the functional significance of this phenotypic transformation to a macrophage-like cell remains incompletely understood. While these processes suggest that SMCs perpetuate plaque formation, SMCs also play a vital role in the formation of the protective fibrous cap characteristic of a later stage atheromas [3].

Figure 4. Inflammation and SMC in Vascular Matrix Remodeling.

Matrix composition regulates SMC proliferation and migration into the neointima, where SMCs play a dominant role in extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis. Macrophages and other leukocytes in the neointima destabilize the plaque by inhibiting ECM synthesis, secreting proteases that degrade the matrix, and promoting SMC apoptosis.

1. Soluble Factors in SMC Phenotype

Activated endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and intimal macrophages all produce various growth factors to stimulate SMC proliferation and phenotypic modulation in the neointima [108]. Classic SMC mitogens, including PDGF-BB, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), angiotensin II, and thrombin, typically act through the extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathway that promotes the expression of cell cycle genes and the Akt pathway that represses the function of cell cycle inhibitors [109]. However, agents that activate cAMP and cGMP production in the SMCs uncouples the ability of these mitogens to stimulate SMC growth [110]. These inhibitory factors may come from the systemic circulation (e.g. adiponectin) or through local paracrine production (e.g. nitric oxide, prostacyclin, resolvins) [110, 111]. The transition from a quiescent, contractile state to the activated phenotype involves a genetic reprogramming associated with the loss of contractile markers, such as α-smooth muscle actin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, and SM22 among others, and enhanced expression of genes associated with fibrosis and inflammation [108, 112]. While PDGF-BB potently represses SMC contractile gene expression, insulin and TGF-β enhance their expression [108, 113]. However, TGF-β also stimulates the expression of extracellular matrix genes [114], suggesting that contractile marker expression does not necessarily distinguish between the quiescent and synthetic SMC phenotypes.

Smooth muscle cells actively contribute to the inflammatory response in the plaque. Cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α activate NF-кB in SMCs to induce the expression of pro-inflammatory genes, such as the cell adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and the chemokines MCP-1 and fractalkine/CXCL1 [105]. Induction of these inflammatory genes typically coincides with the loss of contractile markers; however, this relation may be more than correlative, as SM22α can stabilize the NF-кB inhibitor IкB to reduce proinflammatory gene expression [115]. However, the crosstalk between inflammation and SMC phenotype likely extends well beyond NF-кB, as the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-19 inhibits SMC migration, neointimal hyperplasia, and atherosclerotic plaque formation without affecting NF-кB activation [35, 116]. Expression of cell adhesion molecules, such as VCAM-1, may be functionally important to plaque organization, as electron microscopy of atherosclerotic plaques suggest that SMCs and macrophages are in direct contact [117].

While once thought of as a macrophage-associated response, lineage tracing studies suggest that at least half of the foam cells in atherosclerotic plaques derive from neointimal SMCs [106, 107]. In addition to the LDL receptor, SMCs express a variety of scavenger receptors involved in lipid uptake, including CD36, LOX-1, and LDL receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) [118]. Lipid loading of SMCs enhances their expression of typical macrophage markers (ex. CD68) while decreasing their expression of SMC marker genes (ex. SMA, SM22a) [106], suggesting that these markers may better associate with phagocytic activity rather than cell lineage [119].

2. Matrix and Mechanics in Smooth Muscle Fibroproliferative Remodeling

Vascular SMCs show profoundly disparate responses to different extracellular matrices, suggesting that the matrix environment plays a significant role in regulating smooth muscle function. Neointimal SMCs co-localize with fibronectin during atherosclerotic plaque formation [25, 83], and depletion of plasma fibronectin in atherosclerosis-prone mice significantly reduces atherosclerosis associated with reduced neointimal SMC content and fibrous cap size [83]. Plaque levels of cell-derived EDA-positive fibronectin correlates with a stable plaque phenotype in human endarterectomy samples and mouse models of atherosclerosis [120, 121]. In contrast to provisional matrix proteins, polymerized type I collagen limits SMC proliferation [122], potentially maintaining SMC quiescence under healthy conditions and preventing further neointimal hyperplasia in the absence of injury. This effect may be mediated through the collagen receptor DDR1, which limits SMC proliferation and extracellular matrix synthesis [123]. Increased expression of collagen VIII in the growing plaque binds to and reduces cellular accessibility of collagen I, leading to enhanced cell growth even in the presence of type I collagen [124]. In contrast to polymerized collagen I, monomeric collagen I reduces SMC contractile markers and enhances proliferation and proinflammatory gene expression [112, 125].

Integrin signaling plays a vital role in regulating SMC function. Interactions with laminin through the integrin α7β1 prevents SMC proliferation [126]. The collagen-binding integrin α1β1 is highly expressed in contractile SMCs but suppressed concomitant with the loss of contractile markers [127]. The alternative collagen-binding integrin, α2β1, promotes SMC proliferation and collagen deposition, suggesting that the SMC collagen receptors may play context-dependent roles [128]. Smooth muscle cells express multiple provisional matrix-binding integrins; however, αvβ3 and αvβ5 show particular upregulation in neointimal SMCs [129]. Treatment with inhibitors of αvβ3 but not α5β1 phenocopies the effect of plasma fibronectin deletion, suggesting that fibronectin promotes SMC proliferation through αvβ3 [16, 25]. Consistent with this αvβ3 dominant role, inhibitory antibodies against αvβ3 reduces plaque development in diabetic pigs associated with diminished plaque SMC content [130]. Therefore, matrix regulation of SMC proliferation involves both a change in the composition of the matrix and a change in the expression of matrix receptors that drive integrin-specific signaling pathways that regulate SMC proliferation.

Maintenance of a quiescent, contractile smooth muscle phenotype requires a certain degree of mechanical stress [131, 132]. Cyclic stretch of the vessel wall applies mechanical strain to the medial smooth muscle cells through cell-matrix adhesions; however, other mechanosensors such as ion channels, cell-cell interactions, and the cell nucleus appear to be activated as well [22]. The proliferative response to mechanical stretch in SMCs varies due to experimental conditions, such as the degree of stretch [22]. Normal SMC stretch (<10%) has been shown to reduce SMC proliferation, consistent with stretch-associated SMC quiescence [132, 133]. In contrast, high levels of mechanical stretch promote SMC proliferation and apoptosis, consistent with vascular wall remodeling under excessive mechanical load seen during hypertension [133]. Matrix composition also affects stretch-induced SMC proliferation, with collagen, fibronectin, and vitronectin supporting stretch-induced proliferation, whereas laminin and elastin do not [134]. Inhibition of RGD-binding integrins prevents this matrix-specific response [134], suggesting that the provisional matrix-binding integrins mediate this effect. Low levels of tissue stiffness decreases proliferation in a wide variety of cell types due to a decrease in integrin signaling, suggesting that tissue stiffness itself regulates local proliferative capacity [135]. Matrix stiffness regulates cyclin D1-dependent Rb phosphorylation and S phase entry in smooth muscle cells [135], and preventing matrix stiffening by inhibiting matrix cross-linking reduces SMC proliferation in vitro and limits plaque burden in vivo [136]. Taken together, these data suggest that alteration in integrin signaling through changes in matrix composition coupled to alterations in mechanical load transmitted to these integrin adhesions play a large role in regulating SMC proliferation during neointima formation.

F. Collective Adaptation of the Microenvironment

Nearly 30 years ago, Dr. Mina Bissell put forth the notion that cells and their extracellular matrix exist in a state of dynamic reciprocity, such that cells remodel their matrix and matrix composition affects cell function [7]. However, this property is not exclusive to the matrix but can be extended to other aspects of the local microenvironment as well, including tissue mechanics and local deposition and activation of soluble mediators. In the following section, we will discuss how individual components of the microenvironment interact to restructure the local environment.

1. Regulation of Subendothelial Matrix Remodeling

Fibronectin deposition into the subendothelial matrix is one of the earliest detectable changes in the vessel during plaque initiation, occurring concomitant with early endothelial activation and prior to monocyte recruitment [12, 137]. Fibronectin circulates in the blood and therefore may be deposited into the endothelial matrix by passive leak. However, endothelial cells also produce and deposit fibronectin in response to a variety of stimuli. Early fibronectin deposition occurs specifically at sites of disturbed flow in models of hypercholesterolemia and hyperglycemia [12, 137]. While disturbed flow can promote NF-κB-dependent fibronectin expression and deposition [138], regions of disturbed flow do not show significant fibronectin deposition in the absence of circulating risk factors. In contrast, exposure to laminar flow significantly reduces fibronectin deposition even in the presence of high glucose levels mimicking diabetes [137, 139]. The TGF-β superfamily (TGF-β, BMPs) drive matrix gene expression and tissue fibrosis by activating the Smad transcription factors [140]. In addition, TGF-β signaling promotes a gene expression program, termed endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), involving the loss of endothelial cell markers (VE-cadherin, CD31), enhanced expression of smooth muscle contractile markers (smooth muscle actin, calponin), and enhanced production of extracelluar matrix genes (fibronectin, fibrillar collagens) [141]. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling limits EndMT through the FGFR1 receptor [142], and laminar shear stress enhances FGFR1 expression and prevents TGF-β-induced EndMT [141, 143]. In contrast, disturbed flow reduces FGFR1 expression, enhances TGFβ signaling, and drives EndMT both in vitro and in vivo [141, 143]. Promoting EndMT through ablating endothelial FGFR1 signaling enhances endothelial fibronectin deposition and significantly augments atherosclerotic plaque development [143]. In addition to fibronectin expression, fibronectin deposition requires the mechanical unraveling of soluble, globular fibronectin dimers through the RGD-binding integrins, revealing cryptic nucleation sites that promote assembly into the fibrillar form. Therefore, stimuli that promote activation of fibronectin-binding integrins or increase endothelial cell contractility, such as disturbed flow and oxLDL, may induce endothelial cells to deposit fibronectin [25, 138]. In contrast, inhibiting fibronectin-binding integrins through down-regulated expression or suppressed activation may reduce fibronectin deposition into the endothelial matrix [84].

2. Regulation of Soluble Factor Deposition and Signaling

The microenvironment regulates the retention of several growth factors and proinflammatory mediators to perpetuate fibroproliferative remodeling and local inflammation within the plaque. TNF-α binds laminin and the N-terminus of fibronectin [144, 145], whereas the TNF-α suppressor IL-4 binds to heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate glycosaminoglycans and tempers TNFα-induced inflammation [146]. In addition, most chemokines bind to heparan sulfate proteoglycans, promoting chemokine oligomerization and local leukocyte recruitment [147]. Interaction with the extracellular matrix affects their local abundance through altered retention, their presentation to receptors on the cell surface, and the signaling function of their activated receptors.

Growth Factors

Extracellular macromolecules contain many growth factor-binding sites and sequester an ever increasing number of growth factors, including IGF, FGF, TGF-β, HGF, and PDGF-BB [148]. Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), carbohydrate side chains attached to proteoglycans, account for the majority of growth factor binding to the extracellular matrix. Interestingly, matrix-bound growth factors signal differently than their soluble counterparts. In vitro studies of soluble growth factors demonstrate that they are rapidly internalized and degraded. However, matrix-bound factors become immobilized and are unable to undergo endocytosis, which promotes constitutive signaling. Growth factors do not always require the presence of GAG-chained proteoglycans for incorporation into the matrix, as conserved protein domains found on many extracellular matrix proteins retain growth factors. For instance, von Willebrand domains in collagen bind TGF-β and PDGF-BB [149]. Cell-matrix interactions also affect signaling through growth factor receptors through direct interactions. Extracellular association of αvβ3 with the PDGF receptor potentiates growth factor receptor signaling to enhance proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis [150], and deposition of αvβ3-binding matrix proteins and elevated matrix stiffness enhance PDGF receptor signaling [151, 152].

Mechanical properties of the microenvironment also regulate bioavailability of growth factors and uncover cryptic sites within extracellular matrix proteins to reveal growth factor binding sites. For example, tension applied to fibronectin monomers exposes growth factor binding sites [153], and atomic force microscopy studies show enhanced growth factor binding to fibronectin under conditions where fibronectin adopts an extended conformation [153]. Reciprocally, extracellular matrix interactions with soluble factors maintains the matrix proteins in an extended or unraveled conformation that also allows for increased integrin binding and prevents proteolysis [154]. TGF-β, secreted in an inactive form due to the latency-associated peptide (LAP) masking TGF-β active sites, interacts with both fibronectin and RGD-binding integrins [155]. Mechanical tension applied to the inactive TGF-β complex results in LAP cleavage and release of active TGF-β.

Modified LDL

Development of atherosclerosis depends on accumulation of systemic apolipoprotein-B containing lipoproteins in the artery wall. Studies using radiolabelled LDL demonstrate that the rate of LDL entry is similar between areas prone or resistant to atherosclerosis [156]. This finding led to the response-to-retention hypothesis, which argues that LDL shows enhanced retention in the artery wall at atherosclerosis-prone sites [157]. Proteoglycans, which change in abundance and type during atherosclerosis, directly bind LDL and mice expressing an LDL defective in proteoglycan-binding develop significantly less atherosclerosis [28, 157]. Versican, biglycan, and decorin represent the predominant vascular proteoglycans, with versican and biglycan enriched in atherosclerosis-prone regions and decorin enriched in atherosclerosis-protected regions [11]. GAG composition of the proteoglycans appear to mediate this differential effect, with chondroitin sulfate GAG chains associated with versican and biglycan showing higher affinity for LDL compared to the dermatan sulfate GAG chains on decorin. Indeed, immunohistochemistry analysis demonstrates striking colocalization between biglycan, versican, and the ApoB moiety on LDL (Figure 3C) [158, 159]. Interestingly, induced expression of the V3 variant of versican lacking GAG chains prevents atherogenic lipid accumulation [160].

3. Inflammation and the Fibrous Cap

Inflammation negatively regulates smooth muscle function and fibrous cap formation. The proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β prevents PDGF-BB-induced SMC migration and neointima formation [161]. Elevated expression of IFN-y in atherosclerotic plaques promotes a vulnerable plaque phenotype by repressing SMC collagen synthesis [162, 163] and enhancing SMC apoptosis [164]. In addition to altered SMC matrix deposition, macrophages produce a staggering array of proteolytic enzymes that not only kill infectious agents but also modify extracellular matrix structure. Excessive production of MMPs by plaque macrophages likely contributes to the destruction of the extracellular matrix resulting in plaque rupture, as increased amounts of several MMPs are found in macrophage-rich regions of human atherosclerotic plaques. MMP-2 and MMP-9 both contribute to atherosclerotic plaque progression, as the MMP-2 and MMP-9 knockout mice display reduced plaque size compared to wild type mice [165, 166]. In addition, macrophages produce multiple members of the cathepsin family of cysteine proteases, well recognized to contribute to atherosclerosis progression. These cathepsins possess strong elastase activity, and cathepsin K and S deficient mice show reduced elastin breaks in the plaque [167, 168]. While these data clearly point to a role for macrophages in matrix turnover, foam cells express a pro-fibrotic gene expression program, including PDGF-BB, TGF-β, and multiple collagen and proteoglycans, suggesting that specific macrophage phenotypes differentially affect matrix remodeling during atherosclerosis [169].

4. Vessel Stiffening and Altered Arterial Mechanics

Stiffness of the extracellular matrix depends both on matrix composition and matrix crosslinking. Elastin fragmentation due to mechanical stress or degradation by proteases reduces tissue compliance resulting in enhanced production of fibrillar collagens to absorb the mechanical load. Elastin fibers demonstrate a half-life of approximately 74 years [170], with most of the elastin fibers in tissue are produced during organism development. Since elastin fiber formation is severely deficient in the adult, damage to elastin fibers during aging and disease causes irreparable tissue dysfunction. Elevated mechanical load promotes SMC expression of both fibrillar collagens and the matrix crosslinking protein lysyl oxidase (Lox) [136, 171]. ApoE knockout mice display elevated vascular stiffness that precedes atherosclerotic plaque formation, and inhibiting Lox-mediated matrix crosslinking significantly reduces both vessel stiffness and plaque formation [136]. ApoE-containing lipoprotein reduces SMC expression of fibrillar collagens, fibronectin, and Lox, suggesting a potential mechanism for this effect [136]. The matrix crosslinking enzyme transglutaminase 2 also shows enhanced expression in the vasculature in models of diet-induced obesity and atherosclerosis, and transglutaminase 2 deficient mice show reduced matrix crosslinking, decreased collagen content, and reduced atherosclerosis [172]. Endothelial-derived NO reduces transglutaminase 2 activity through direct S-nitrosylation [173], and eNOS knockout mice show enhanced transglutaminase activity and vascular stiffness [174]. In addition to enzymatic crosslinking, aging and hyperglycemia associated with diabetes results in non-enzymatic glycation of matrix proteins, crosslinking and stiffening the vascular matrix [41, 175]. Preventing this with the glycation cross linkage breaker alagebrium chloride (ALT-711) reduces neointimal proliferation in a rodent vascular injury model and blunts diabetic atherosclerosis [176, 177].

Stiffening of the vascular smooth muscle cells, due to enhanced actomyosin contractility, has been noted in response to aging and hypertension. However, it is unclear whether this effect is due to cellular reprogramming due to chronic changes in matrix stiffness. The Rho/ROCK pathway responds to enhanced tissue stiffness and stiffens the actin cytoskeletal through enhanced actomyosin contractility. Like matrix stiffness, paracrine signaling from the endothelium can inhibit SMC Rho/ROCK signaling by multiple pathways, including the NO/PKG and PGI2/PKA pathways [178, 179]. PKA and PKG inhibit Rho-mediated SMC stiffening at multiple levels, both directly through RhoA phosphorylation and inactivation and indirectly through activation of the inhibitory myosin phosphatase pathway [178, 180]. Highlighting the importance of these protective pathways, Ang II infusion induces aortic stiffness in mice only in context of NO deficiency [181], consistent with the enhanced vascular stiffness observed in eNOS knockout mice [174].

G. Future Directions

While these studies clearly suggest that arterial microenvironment crosstalks with systemic risk factors to regulate local plaque production, there are several areas limiting our understanding of microenvironmental control of atherogenesis. Neointimal proteoglycans affect the deposition of oxLDL, chemokines, and mitogenic growth factors in the growing plaque [11]. However, additional research is needed to define the specific roles of individual GAGs and the role of differential GAG sulfation patterns, which can significantly affect binding affinity. Changes in the endothelial basement membrane alter endothelial activation by disturbed flow patterns and oxLDL [12, 25]. However, the molecular mechanisms mediating subendothelial matrix remodeling at atherosclerosis-prone sites remains largely unknown. Additionally, we currently do not understand the molecular mechanisms by which the basement membrane exerts its protective effect limiting endothelial activation, nor do we fully understand how different provisional matrix-binding integrins exert their context-dependent proinflammatory signaling. Promoting endothelial NO production provides several protective effects, including reduced inflammation, inhibition of SMC proliferation, and diminished vessel stiffening [41]. However, efforts to increase endothelial NO production must be carefully targeted to reduce NO interaction with superoxide, resulting in the formation of the damaging free radical species peroxynitrite. Matrix signaling affects multiple aspects of SMC function, including proliferation, migration, and gene expression. However, inhibitors of SMC proliferation and migration might induce a vulnerable plaque phenotype by limiting fibrous cap formation. Efforts should be directed at promoting a stable fibrous cap by limiting proteolysis, and enhancing collagen polymerization, thereby promoting SMC quiescence in the presence of a mature, mechanically stable matrix. Lastly, macrophages exhibit significant phenotypic differences based upon their microenvironment. However, there is currently a paucity of data on the microenvironmental components regulating macrophage function, particularly in the context of atherosclerosis. More research is needed in this area to define how the arterial microenvironment contributes to chronic inflammation in the vessel wall.

Summary Statement.

Changes in the local microenvironment regulate multiple aspects of vascular and inflammatory cell phenotype, determining the location, composition, and clinical consequences of atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by a National Institute of Health R01 (HL098435) and an American Heart Association Grant-In-Aid (15GRNT25560056) to A.W. Orr, and by the American Heart Association Pre-doctoral Fellowship (14PRE18660003) to A. Yurdagul Jr.

Abbreviations

- 13-HODE

13-hydroxy-9Z, 11E-oxtadecadienoic acid

- AcLDL

acetylated low density lipoprotein

- JNK

c-jun N-terminal kinase

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pathogen

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ERK

extracellular signal regulated kinase

- EndMT

endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- EDA

extradomain A

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR1

FGF receptor 1

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IFNγ

interferon-γ

- IL

interleukin

- Klf2

kruppel-like factor 2

- LAP

latency associated peptide

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- LDLR

LDL receptor

- LRP1

LDL receptor-related protein-1

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MCP-1

macrophage chemotactic protein-1

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NO

nitric oxide

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- oxLDL

oxidized LDL

- PAK

p21 activated kinase

- PDGF-BB

platelet-derived growth factor-BB

- PKA

protein kinase A

- SMC

smooth muscle cells

- SREBP2

sterol regulatory element binding protein 2

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor β

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

References

- 1.Libby P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2004–2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1216063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn C, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:53–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huveneers S, Daemen MJ, Hordijk PL. Between Rho(k) and a hard place: the relation between vessel wall stiffness, endothelial contractility, and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:895–908. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozbek S, Balasubramanian PG, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Tucker RP, Adams JC. The evolution of extracellular matrix. Molecular biology of the cell. 2010;21:4300–4305. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bissell MJ, Aggeler J. Dynamic reciprocity: how do extracellular matrix and hormones direct gene expression? Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987;249:251–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2014;15:786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrm3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stratman AN, Davis GE. Endothelial cell-pericyte interactions stimulate basement membrane matrix assembly: influence on vascular tube remodeling, maturation, and stabilization. Microsc Microanal. 2012;18:68–80. doi: 10.1017/S1431927611012402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes MJ, Farndale RW. Collagens and atherosclerosis. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34:513–525. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakashima Y, Wight TN, Sueishi K. Early atherosclerosis in humans: role of diffuse intimal thickening and extracellular matrix proteoglycans. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:14–23. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orr AW, Sanders JM, Bevard M, Coleman E, Sarembock IJ, Schwartz MA. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates NF-kappaB activation by flow: a potential role in atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:191–202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukhova GK, Shi GP, Simon DI, Chapman HA, Libby P. Expression of the elastolytic cathepsins S and K in human atheroma and regulation of their production in smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:576–583. doi: 10.1172/JCI181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz MA. Integrin signaling revisited. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:466–470. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Green J, Yurdagul A, Jr, Albert P, McInnis MC, Orr AW. αvβ3 Integrins Mediate Flow-Induced nf-кb Activation, Proinflammatory Gene Expression, and Early Atherogenic Inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.05.013. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hultgardh-Nilsson A, Durbeej M. Role of the extracellular matrix and its receptors in smooth muscle cell function: implications in vascular development and disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:540–545. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282ef77e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orr AW, Helmke BP, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. Mechanisms of mechanotransduction. Dev Cell. 2006;10:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baeyens N, Schwartz MA. Biomechanics of vascular mechanosensation and remodeling. Molecular biology of the cell. 2016;27:7–11. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HJ, Li N, Evans SM, Diaz MF, Wenzel PL. Biomechanical force in blood development: extrinsic physical cues drive pro-hematopoietic signaling. Differentiation. 2013;86:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu X, Pandit A, Kassab GS. Biaxial incremental homeostatic elastic moduli of coronary artery: two-layer model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1663–1669. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00226.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haga JH, Li YS, Chien S. Molecular basis of the effects of mechanical stretch on vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biomech. 2007;40:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daugherty A. Mouse models of atherosclerosis. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2002;323:3–10. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birukov KG. Oxidized lipids: the two faces of vascular inflammation. Current atherosclerosis reports. 2006;8:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s11883-006-0077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yurdagul A, Jr, Green J, Albert P, McInnis MC, Mazar AP, Orr AW. alpha5beta1 integrin signaling mediates oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced inflammation and early atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1362–1373. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitan I, Volkov S, Subbaiah PV. Oxidized LDL: diversity, patterns of recognition, and pathophysiology. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2010;13:39–75. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skalen K, Gustafsson M, Rydberg EK, Hulten LM, Wiklund O, Innerarity TL, Boren J. Subendothelial retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in early atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;417:750–754. doi: 10.1038/nature00804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhn H, Wiesner R, Lankin VZ, Nekrasov A, Alder L, Schewe T. Analysis of the stereochemistry of lipoxygenase-derived hydroxypolyenoic fatty acids by means of chiral phase high-pressure liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:24–34. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhn H, Heydeck D, Hugou I, Gniwotta C. In vivo action of 15-lipoxygenase in early stages of human atherogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;99:888–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI119253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramji DP, Davies TS. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: Key players in all stages of disease and promising therapeutic targets. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nunez G, Schnurr M, Espevik T, Lien E, Fitzgerald KA, Rock KL, Moore KJ, Wright SD, Hornung V, Latz E. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barlis P, Serruys PW, Devries A, Regar E. Optical coherence tomography assessment of vulnerable plaque rupture: predilection for the plaque ‘shoulder’. European heart journal. 2008;29:2023. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gieseg SP, Amit Z, Yang YT, Shchepetkina A, Katouah H. Oxidant production, oxLDL uptake, and CD36 levels in human monocyte-derived macrophages are downregulated by the macrophage-generated antioxidant 7,8-dihydroneopterin. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2010;13:1525–1534. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellison S, Gabunia K, Kelemen SE, England RN, Scalia R, Richards JM, Orr AW, Traylor JG, Jr, Rogers T, Cornwell W, Berglund LM, Goncalves I, Gomez MF, Autieri MV. Attenuation of experimental atherosclerosis by interleukin–19. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2316–2324. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.England RN, Preston KJ, Scalia R, Autieri MV. Interleukin-19 decreases leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions by reduction in endothelial cell adhesion molecule mRNA stability. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C255–265. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00069.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janmale T, Genet R, Crone E, Flavall E, Firth C, Pirker J, Roake JA, Gieseg SP. Neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin are generated within atherosclerotic plaques. Pteridines. 2015;26:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baird SK, Reid L, Hampton MB, Gieseg SP. OxLDL induced cell death is inhibited by the macrophage synthesised pterin, 7,8-dihydroneopterin, in U937 cells but not THP-1 cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2005;1745:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pober JS, Sessa WC. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:803–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collins T, Cybulsky MI. NF-kappaB: pivotal mediator or innocent bystander in atherogenesis? Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107:255–264. doi: 10.1172/JCI10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Funk SD, Yurdagul A, Jr, Orr AW. Hyperglycemia and endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis: lessons from type 1 diabetes. Int J Vasc Med. 2012;2012:569654. doi: 10.1155/2012/569654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Partridge J, Carlsen H, Enesa K, Chaudhury H, Zakkar M, Luong L, Kinderlerer A, Johns M, Blomhoff R, Mason JC, Haskard DO, Evans PC. Laminar shear stress acts as a switch to regulate divergent functions of NF-kappaB in endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:3553–3561. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-8059com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsao PS, Buitrago R, Chan JR, Cooke JP. Fluid flow inhibits endothelial adhesiveness. Nitric oxide and transcriptional regulation of VCAM-1. Circulation. 1996;94:1682–1689. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.7.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.SenBanerjee S, Lin Z, Atkins GB, Greif DM, Rao RM, Kumar A, Feinberg MW, Chen Z, Simon DI, Luscinskas FW, Michel TM, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Garcia-Cardena G, Jain MK. KLF2 Is a novel transcriptional regulator of endothelial proinflammatory activation. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1305–1315. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baeyens N, Mulligan-Kehoe MJ, Corti F, Simon DD, Ross TD, Rhodes JM, Wang TZ, Mejean CO, Simons M, Humphrey J, Schwartz MA. Syndecan 4 is required for endothelial alignment in flow and atheroprotective signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:17308–17313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413725111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grumbach IM, Chen W, Mertens SA, Harrison DG. A negative feedback mechanism involving nitric oxide and nuclear factor kappa-B modulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase transcription. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yurdagul A, Jr, Chen J, Funk SD, Albert P, Kevil CG, Orr AW. Altered nitric oxide production mediates matrix-specific PAK2 and NF-kappaB activation by flow. Molecular biology of the cell. 2013;24:398–408. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleming I. Molecular mechanisms underlying the activation of eNOS. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:793–806. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto K, Furuya K, Nakamura M, Kobatake E, Sokabe M, Ando J. Visualization of flow-induced ATP release and triggering of Ca2+ waves at caveolae in vascular endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3477–3483. doi: 10.1242/jcs.087221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrews AM, Jaron D, Buerk DG, Barbee KA. Shear stress-induced NO production is dependent on ATP autocrine signaling and capacitative calcium entry. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2014;7:510–520. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0351-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang S, Iring A, Strilic B, Albarran Juarez J, Kaur H, Troidl K, Tonack S, Burbiel JC, Muller CE, Fleming I, Lundberg JO, Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. P2Y(2) and Gq/G(1)(1) control blood pressure by mediating endothelial mechanotransduction. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3077–3086. doi: 10.1172/JCI81067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lakshmikanthan S, Zheng X, Nishijima Y, Sobczak M, Szabo A, Vasquez-Vivar J, Zhang DX, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Rap1 promotes endothelial mechanosensing complex formation, NO release and normal endothelial function. EMBO reports. 2015;16:628–637. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCormick ME, Collins C, Makarewich CA, Chen Z, Rojas M, Willis MS, Houser SR, Tzima E. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 mediates endothelial-cardiomyocyte communication and regulates cardiac function. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001210. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boo YC, Sorescu G, Boyd N, Shiojima I, Walsh K, Du J, Jo H. Shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase at Ser1179 by Akt-independent mechanisms: role of protein kinase A. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:3388–3396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuentes E, Palomo I. Extracellular ATP metabolism on vascular endothelial cells: A pathway with pro-thrombotic and anti-thrombotic molecules. Vascul Pharmacol. 2015;75:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanthi Y, Hyman MC, Liao H, Baek AE, Visovatti SH, Sutton NR, Goonewardena SN, Neral MK, Jo H, Pinsky DJ. Flow-dependent expression of ectonucleotide tri(di)phosphohydrolase-1 and suppression of atherosclerosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015;125:3027–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI79514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wen J, Grenz A, Zhang Y, Dai Y, Kellems RE, Blackburn MR, Eltzschig HK, Xia Y. A2B adenosine receptor contributes to penile erection via PI3K/AKT signaling cascade-mediated eNOS activation. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011;25:2823–2830. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-181057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buchheiser A, Ebner A, Burghoff S, Ding Z, Romio M, Viethen C, Lindecke A, Kohrer K, Fischer JW, Schrader J. Inactivation of CD73 promotes atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Cardiovascular research. 2011;92:338–347. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Orr AW, Hahn C, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. p21-activated kinase signaling regulates oxidant-dependent NF-kappa B activation by flow. Circ Res. 2008;103:671–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cuhlmann S, Van der Heiden K, Saliba D, Tremoleda JL, Khalil M, Zakkar M, Chaudhury H, Luong le A, Mason JC, Udalova I, Gsell W, Jones H, Haskard DO, Krams R, Evans PC. Disturbed blood flow induces RelA expression via c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1: a novel mode of NF-kappaB regulation that promotes arterial inflammation. Circulation research. 2011;108:950–959. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orr AW, Stockton R, Simmers MB, Sanders JM, Sarembock IJ, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. Matrix-specific p21-activated kinase activation regulates vascular permeability in atherogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:719–727. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hahn C, Orr AW, Sanders JM, Jhaveri KA, Schwartz MA. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates JNK activation by flow. Circulation research. 2009;104:995–1003. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heo KS, Chang E, Le NT, Cushman H, Yeh ET, Fujiwara K, Abe J. De-SUMOylation enzyme of sentrin/SUMO-specific protease 2 regulates disturbed flow-induced SUMOylation of ERK5 and p53 that leads to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2013;112:911–923. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le NT, Heo KS, Takei Y, Lee H, Woo CH, Chang E, McClain C, Hurley C, Wang X, Li F, Xu H, Morrell C, Sullivan MA, Cohen MS, Serafimova IM, Taunton J, Fujiwara K, Abe J. A crucial role for P90RSK-mediated reduction of ERK5 transcriptional activity in endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2013;127:486–499. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.116988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Z, Martin M, Li Z, Shyy JY. Endothelial dysfunction: the role of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-induced NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing protein 3 inflammasome in atherosclerosis. Current opinion in lipidology. 2014;25:339–349. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Z, Wen L, Martin M, Hsu CY, Fang L, Lin FM, Lin TY, Geary MJ, Geary GG, Zhao Y, Johnson DA, Chen JW, Lin SJ, Chien S, Huang HD, Miller YI, Huang PH, Shyy JY. Oxidative stress activates endothelial innate immunity via sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SREBP2) transactivation of microRNA-92a. Circulation. 2014;131:805–814. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiao H, Lu M, Lin TY, Chen Z, Chen G, Wang WC, Marin T, Shentu TP, Wen L, Gongol B, Sun W, Liang X, Chen J, Huang HD, Pedra JH, Johnson DA, Shyy JY. Sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in endothelium mediates hemodynamic-induced atherosclerosis susceptibility. Circulation. 2013;128:632–642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]