Significance

High attrition from educational programs is a major obstacle to social mobility and a persistent source of economic inefficiency. Over two-thirds of students entering a 2-y institution fail to earn a credential in the United States. In online courses, attrition rates are even higher. In two large field experiments, we tested the conditions under which a writing activity that facilitates goal commitment and goal-directed behavior reduces attrition in online courses. The activity raised completion rates by up to 78% for members of individualist cultures and primarily for those who contended with predictable and surmountable obstacles in the form of everyday obligations, but it was ineffective in collectivist cultures and for people contending with other types of obstacles.

Keywords: motivation, goal pursuit, culture, education, field experiment

Abstract

Academic credentials open up a wealth of opportunities. However, many people drop out of educational programs, such as community college and online courses. Prior research found that a brief self-regulation strategy can improve self-discipline and academic outcomes. Could this strategy support learners at large scale? Mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII) involves writing about positive outcomes associated with a goal, the obstacles to achieving it, and concrete if–then plans to overcome them. The strategy was developed in Western countries (United States, Germany) and appeals to individualist tendencies, which may reduce its efficacy in collectivist cultures such as India or China. We tested this hypothesis in two randomized controlled experiments in online courses (n = 17,963). Learners in individualist cultures were 32% (first experiment) and 15% (second experiment) more likely to complete the course following the MCII intervention than a control activity. In contrast, learners in collectivist cultures were unaffected by MCII. Natural language processing of written responses revealed that MCII was effective when a learner’s primary obstacle was predictable and surmountable, such as everyday work or family obligations but not a practical constraint (e.g., Internet access) or a lack of time. By revealing heterogeneity in MCII’s effectiveness, this research advances theory on self-regulation and illuminates how even highly efficacious interventions may be culturally bounded in their effects.

People face many obstacles in the pursuit of their educational goals. In the United States, only 59% of students entering 4-y institutions earn bachelor’s degrees within 6 y, and less than a third of those entering 2-y institutions earn a credential within 3 y (1). Compared with brick-and-mortar schools, online education can provide more flexible and affordable opportunities for intellectual and professional development. Between 2011 and 2015, over 35 million people worldwide enrolled in massive open online courses (MOOCs) to gain access to a basic higher education, to advance their career, or to engage in lifelong learning (2, 3). Services that support lifelong learning, such as MOOCs, are increasingly important in the digital economy where employees need to acquire new skills and knowledge to remain competitive. MOOCs have increased access to the opportunities of higher education, including access to course lectures, conceptual and practical assessments, and social capital (4). However, course completion rates typically fall below 10% and still do not exceed 25% for highly committed learners (5, 6). This shortcoming has been attributed to insufficient support and guidance for learners with weak self-regulatory skills (7, 8).

Self-regulation is the process by which people change their beliefs and actions in the pursuit of their goals (9). It is known to support achievement in academic settings (10–13). In contrast to students in traditional school settings whose time is structured around classes in a fixed schedule, online learners are expected to determine when and how to engage with course content. They confront no external pressures to make progress or explicit social norms to facilitate course completion. Learners receive relatively little support and guidance in online learning environments, and as a result, many struggle with self-regulation (14). However, digital learning environments can be used to disseminate not only educational content but also activities that support self-regulation. Guided activities that were found to support academic self-regulation in prior research could be made available to large numbers of online learners and tested at scale. The international audience of learners in MOOCs offers an unprecedented opportunity to explore heterogeneity in the effects of self-regulation strategies and their ecological validity in authentic learning environments (15).

Mental Contrasting with Implementation Intentions

Previous research has developed a self-regulation strategy called mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII). The strategy builds on a two-stage process of goal pursuit: goal setting, which involves choosing goals and committing to them, and goal striving, which involves planning and executing goal-relevant behavior (16). MCII promotes goal attainment by combining two complementary self-regulation techniques: first, mental contrasting (MC), which instigates goal commitment and goal striving, and second, forming implementation intentions (II), which promote goal-directed behavior through strategic planning for obstacles (17, 18).

The MC procedure consists of vividly elaborating on positive outcomes associated with attaining a goal (e.g., learning a new skill) followed by vividly elaborating on central hindrances in the present that might interfere (e.g., a busy work schedule) (19). By juxtaposing the desired future with current obstacles, MC can strengthen goal commitment and striving (18). Insofar as the obstacles to goal attainment are seen as surmountable, MC induces a sense that the desired future is within one’s reach, thereby increasing commitment and effortful goal striving. By contrast, for goals perceived as insurmountable, MC may reduce commitment because it highlights the difficulty of achieving one’s goals. Intervention studies attest to the positive effects of MC on time management and academic performance (20, 21). The effects are mediated by both cognitive and motivational mechanisms. Cognitively, MC strengthens the mental link between future and present, as assessed by the speed with which people associate future-relevant with present-relevant words, and it recasts present barriers as challenges to overcome (22). Motivationally, MC has an energizing effect that manifests in increased systolic blood pressure and behavior change (23).

The II procedure helps people plan how to overcome obstacles and execute goal-directed actions. It encourages people to generate concrete if–then plans (24, 25). Unlike unstructured planning, an II links a specific situation to a goal-directed action. An example of an II is, “If I feel too tired after work to watch the next lecture, then I will make myself coffee to stay awake.” Forming an II facilitates goal attainment because it increases the likelihood that people will respond efficiently and even automatically to regular obstacles that threaten the completion of their goals (26). Prior work demonstrates the efficacy of II in supporting goal attainment in various contexts, yielding medium-to-large effect sizes (metaanalysis Cohen’s d = 0.65) (27).

MC and II are complementary strategies, because MC promotes goal commitment and striving, whereas II promotes goal-directed behavior in the face of obstacles (17). Twelve studies have tested the combined MCII strategy in the education, health, and conflict resolution domain (11, 28–35) (Table S1). Study samples ranged from 51 to 256 participants, all based in the United States or Germany, with mostly medium-to-large positive effects, including long-term effects in the health domain (29, 34, 35). MCII was also found to be more effective than either MC or II alone at reducing unhealthy snacking (28) and at improving joint agreement in bargaining (32), although no prior work has simultaneously evaluated MC, II, and MCII against a control activity, a gap we address in our second experiment.

Table S1.

Prior published MCII interventions with study characteristics and results

| Publication | Domain | Intervention | N | Country | Population | Results |

| Adriaanse et al., 2010 (28) (two studies) | Health | MCII vs. control; MCII vs. MC vs. II | 51; 59 | Germany; United States | Female college students | Less unhealthy snacking after MCII than control (average partial η2 = 0.16) and after MC (partial η2 = 0.13) or II (partial η2 = 0.25) separately |

| Christiansen et al., 2010 (29) | Health | MCII plus cognitive behavioral therapy vs. standard program | 60 | Germany | Chronic back pain patients | Improved physical capacity after 3 mo (average d = 0.65) |

| Duckworth et al., 2011 (11) | Education | MCII vs. control | 66 | United States | High school students | 60% more practice examinations completed |

| Duckworth et al., 2013 (30) | Education | MCII vs. positive thinking control | 76 | United States | Middle school students | Improved grades, attendance, and conduct (average η2 = 0.06) |

| Gawrilow et al., 2012 (31) | Education | MCII plus learning styles vs. only learning styles | 116 | Germany | Middle school students | Improved self-regulation 2 wk later (d = 0.16), stronger if at risk for ADHD |

| Kirk et al., 2013 (32) | Conflict Resolution | MCII vs. MC vs. II | 132 | Germany | College students | 6% higher joint agreement with MCII than II, but MC was not significantly better than II or worse than MCII |

| Oettingen et al., 2015 (33) (three studies) | Education | MCII vs. two controls; MCII vs. control; MCII vs. control | 84; 51; 58 | Germany; United States; United States | College students; college students; female adults | Increased advanced scheduling of activities; improved reported time management (partial η2 = 0.21); increased school attendance only for the busy |

| Stadler et al., 2009 (34) | Health | MCII plus information vs. only information | 255 | Germany | Female adults | Increase in self-reported fruit/vegetable intake in both conditions, but lasting effect only for MCII (28% above baseline after 2 y) |

| Stadler et al., 2010 (35) | Health | MCII plus information vs. only information | 256 | Germany | Female adults | Higher self-reported physical activity during 4 mo (d = 0.43, 0.47, 0.53, and 0.47) |

In summary, empirical evidence has established that MCII works in different domains and for different age groups. However, no prior work has tested MCII outside Western individualist culture. If the intervention produced medium-to-large increases in online course completion, it would help millions of learners worldwide achieve their educational goals. Can MCII support goal pursuit at scale in cultures around the world?

Sources of Cultural Heterogeneity

MCII may prove most effective in Western individualist countries, because it requires personal agency and an ability and a willingness to structure, even integrate, complex and uncertain life situations into controllable routines. These tendencies are characteristic of the independent self and of analytic cognition dominant in individualist cultures (36, 37). The if–then structure of II, for instance, is rooted in the analytic system of formal logic. By contrast, the collectivist cultural tradition is more holistic and relies on dialectic thinking to reconcile logical contradictions (37). In collectivist cultures, personal goals are subordinate to striving for interpersonal harmony, which sometimes means subordinating personal goals to social goals and negotiating competing obligations (36). It may therefore be culturally incongruent and even threatening to ask people in collectivist cultures to single out personal goals, to generate personally favored outcomes associated with achieving these goals, and to predefine paths for overcoming obstacles to their goals, especially if many of these obstacles revolve around social commitments (38). MCII may be consistent with individually oriented achievement motives that focus on personal goal attainment and controllable dilemmas that can be addressed analytically. However, it may be less aligned with the socially oriented achievement motives that prevail in many collectivist cultures, where people desire to meet the expectations of socially significant others and to accommodate to the unpredictable demands of a complex and ritualized social world (36, 38).

The present work evaluates the efficacy of MCII across cultural contexts. First, we report findings from a cross-cultural survey of online learners that compares views on personal agency, motivation, and handling of complex and uncertain life situations. Then, we report results of two large-scale randomized field experiments with international samples of adult online learners. In the two experiments, we implemented MCII (and MC and II separately) in MOOCs by offering it as a preparatory activity at the beginning of the course. Beyond estimating overall effects, we focus on identifying heterogeneity in treatment effects by cultural context, operationalized based on Hofstede et al.’s (39) national index of collectivism–individualism. Furthermore, leveraging the unprecedented size of our sample for the evaluation of MCII, we applied natural language processing to learners’ stated obstacles to examine the types of obstacles that lent themselves to MCII’s effectiveness. According to the theory of fantasy realization on which MC is based, the intervention should help people cope with obstacles that leave them with some freedom to act adaptively and flexibly, rather than obstacles that are rigidly defined and leave little room for autonomous action (19).

Cross-Cultural Survey

To investigate cultural differences that may influence the efficacy of MCII, we conducted a survey of people from the United States (n = 94) and India (n = 101) who had taken at least one online course over the past 12 mo. Respondents were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk. The United States is the most represented individualist country among MOOC learners, whereas India is the most represented collectivist country. We first evaluated whether MCII’s underlying assumption of a navigable environment and personal agency was more characteristic of individualist than collectivist cultures. Indeed, relative to US respondents, Indian respondents reported that their social environment was more complex and that they shied away from forming if–then plans. Indian respondents listed more obstacles that could interfere with the goal of achieving a good grade in an online course than US respondents (India median = 4, US median = 3; Kruskal–Wallis X2 = 9.50, P = 0.002). They were also more likely to report that if–then plans oversimplify the complexity and ignore the uncertainty of real-life situations [t(192) = 3.12, P = 0.002, d = 0.45].

We also examined cultural differences in how people handle their obstacles. Indian respondents were more likely to use their social relationships than US respondents. We asked respondents how they dealt with obstacles by selecting one or more of the following options: (i) I plan future actions by identifying a specific situation and planning my response; (ii) I get social support by asking people close to me to help me find ways to overcome the obstacle; and (iii) I seek social accountability by asking people who are close to me to monitor my progress and make me feel guilty if I do not make progress toward the goal. Respondents in both countries were equally likely to deal with obstacles by planning ahead (X2 = 1.59, P = 0.21) and asking for help (X2 = 0.02, P = 0.89). However, 31% of Indian respondents, compared with only 4% of US respondents, reported seeking social accountability (X2 = 21.3, P < 0.001). Additionally, although Indian respondents were only slightly more motivated “to feel proud of [their] academic achievements” than US respondents (X2 = 4.82, P = 0.028), they were substantially more motivated by a desire not “to disappoint [their] family and friends with academic failures” (X2 = 17.3, P < 0.001).

In summary, members of a more collectivist culture construed their goal-regulation efforts in a more social and complex context. Insofar as MCII requires an agentic self that can act on a predictable environment, it may be less effective in collectivist than individualist cultures.

Self-Regulation Intervention Experiments

We conducted two randomized controlled trials in distinct online courses to evaluate the effects of MCII. The first experiment ran in a graduate-level business course offered over 10 wk. The second ran in an introductory computer science course offered over 6 wk. The intervention activities were implemented at the start of each course (Materials and Methods). Participants were assigned to receive either an MCII or a control activity in the first experiment. In the second experiment, we added two separate conditions to isolate the effects of MC and II alone. The outcome measure was course completion, that is, whether a participant finished the course and achieved the required final grade to be eligible for a course certificate. We operationalize culture at a national level using the Hofstede collectivism–individualism dimension (39), which assigns a score from 0 (most collectivist) to 100 (most individualist) to 94 nations worldwide. Based on their geographic location, each participant was labeled as belonging in either a collectivist culture ([0, 33]; e.g., Mexico, China, Romania), balanced culture ([34, 66]; e.g., India, Brazil, Russia), or individualist culture ([67, 100]; e.g., United States, Australia, France). For more information on this measure and alternative operationalizations of culture, SI Supporting Analyses.

Before random assignment and exposure to different conditions, participants indicated their likelihood of watching most lectures in the course (from “extremely unlikely,” 1, to “extremely likely,” 7) and the importance they attached to this goal (from “not at all important,” 1, to “extremely important,” 5). Across both experiments, 65% of participants rated the goal as at least “very important” and “very likely” to be attained. Their ratings did not differ significantly between experimental conditions either overall or within each cultural context (Ps > 0.093; Table 1). Participants spent more time completing the MCII activity and were more likely to leave it unfinished than the other activities (Ps < 0.001; see intervention compliance in Table 1). However, this variation does not bias our inferences, because we analyze data from all exposed participants regardless of their compliance with the activities. This intent-to-treat analysis yields conservative estimates of average treatment effects that are relevant to evaluating the overall impact of the intervention. We analyzed participant-level data using linear probability models with robust standard errors and pretreatment self-report measures as covariates (results are robust to using logistic mixed-effects models and to modeling individualism as a continuous variable; SI Supporting Analyses).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for two randomized field experiments by condition

| First experiment | Second experiment | |||||

| Condition | Control | MCII | Control | MC | II | MCII |

| N (countries) | 3,112 (85) | 6,507 (86) | 2,123 (81) | 2,082 (79) | 1,972 (78) | 2,167 (78) |

| Intervention compliance rate, % | 94.7 | 77.5 | 95.9 | 94.1 | 97.9 | 83.8 |

| Median time spent on intervention, min | 5.0 | 8.0 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 6.6 |

| Self-report measures, quartiles | ||||||

| Goal importance | [4, 4, 5] | [4, 4, 5] | [4, 4, 5] | [4, 4, 5] | [4, 4, 5] | [4, 4, 5] |

| Likelihood of attainment | [5, 6, 6] | [5, 6, 6] | [5, 6, 7] | [5, 6, 7] | [5, 6, 7] | [5, 6, 7] |

| Course completion rate | ||||||

| Overall, % | 5.42 | 6.32 | 25.4 | 25.7 | 25.9 | 27.5 |

| Individualist countries, % | 5.52 | 7.28 | 25.7 | 24.8 | 26.2 | 29.5 |

| Balanced countries, % | 5.64 | 5.93 | 25.8 | 25.7 | 25.9 | 24.2 |

| Collectivist countries, % | 5.03 | 4.80 | 23.5 | 29.9 | 24.5 | 21.1 |

Results

Across all cultural contexts, MCII did not significantly increase course completion relative to the control condition in either experiment, although there was a positive trend (experiment 1: b = 0.008, z = 1.66, P = 0.097; experiment 2: b = 0.021, z = 1.54, P = 0.122). MC and II alone did not significantly increase course completion in the second experiment (bs < 0.005, zs < 0.37, Ps > 0.71).

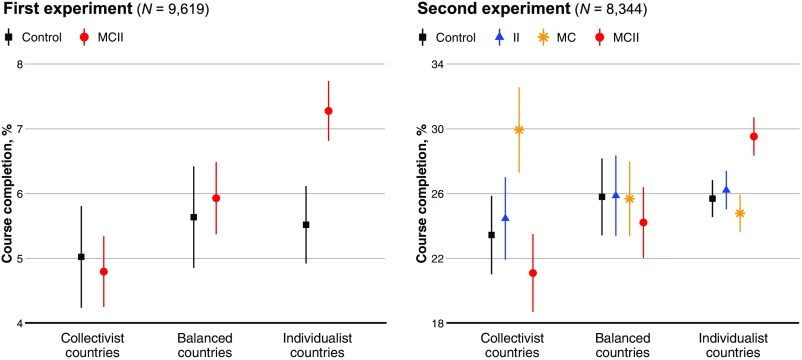

However, once we evaluated the effect of MCII separately by cultural context, we found large effects in individualist countries only (Fig. 1). MCII increased course completion by 32% (experiment 1: b = 0.018, z = 2.35, P = 0.019) and 15% (experiment 2: b = 0.039, z = 2.41, P = 0.016) for participants in individualist countries, relative to the control condition. In contrast, MCII did not raise course completion in collectivist and culturally balanced countries (experiment 1: |bs| < 0.004, |zs| < 0.38, Ps > 0.70; experiment 2: |bs| < 0.023, |zs| < 0.67, Ps > 0.51). Despite the positive impact of MCII in individualist countries, MC and II alone caused no statistically significant improvement in course completion for participants in any cultural context in the second experiment relative to the control condition (MC: |bs| < 0.07, |zs| < 1.83, Ps > 0.067; II: |bs| < 0.01, |zs| < 0.38, Ps > 0.71). However, we unexpectedly found a trend for MC to increase course completion in collectivist countries (b = 0.07, z = 1.83, P = 0.068), discussed below. The key finding is that, in both experiments, MCII was highly effective for learners in individualist cultures, but not for those in collectivist and balanced cultures.

Fig. 1.

MCII raises course completion only among learners in individualist countries. Course completion outcomes of two randomized field experiments evaluating the effect of mental contrasting (MC), implementation intentions (II), and mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII) relative to a control activity in three cultural contexts defined by the Hofstede collectivism–individualism index: collectivist countries [0, 33], balanced countries [34, 66], and individualist countries [67, 100]. Error bars represent ±1 SE.

Given the earlier finding that Indian respondents viewed if–then plans as oversimplifications, we tested whether participants in collectivist and balanced cultures were less likely than participants in individualist cultures to adhere to the if–then structure when forming II. The following results focus on participants’ written responses to the intervention activity. In the first experiment, 41% of participants in individualist countries but only 32% in nonindividualist countries wrote “if” and “then” when instructed to do so (X2 = 54, P < 0.001). In the second experiment, where “If …, then …” was provided as an explicit prompt, 24% of participants from individualist countries deleted the prompt, whereas 28% of participants from nonindividualist countries did (X2 = 6.8, P = 0.009). These differences did not seem to reflect less engagement with the activity in nonindividualist cultures: Participants in nonindividualist countries wrote almost as much as participants in individualist countries in response to the II prompt; whatever difference existed could be accounted for by the deletion of the words “if” and “then” (median word count: 10 vs. 12 in experiment 1, 14 vs. 15 in experiment 2).

Finally, we examined heterogeneous effects of MCII by what kind of obstacle participants faced. We identified each participant’s primary obstacle using topic modeling—a natural language-processing technique—of the 17,963 written descriptions of obstacles that we collected in both experiments. Three thematic clusters of obstacles emerged from the data (most frequent topical terms in parentheses): everyday obligations (work, job, life, family, busy, schedule), lack of time (time, lack, constraint, enough, find, available), and practical barriers (Internet, computer, language, video, understand). Participants were categorized into one of three groups based on the classification of their primary obstacle. Although all three obstacles were commonly indicated in each cultural context, everyday obligations and a lack of time were somewhat more frequent in individualist cultures, whereas practical barriers were somewhat more frequent in collectivist cultures in both experiments (Table S2; X2s > 88, df = 2, Ps < 0.001).

Table S2.

Primary obstacles thematically clustered using topic modeling and relative prevalence of obstacle in individualist, balanced, and collectivist cultural contexts

| Everyday obligation | Lack of time | Practical barrier | |

| Ten most representative words for the topic in descending order | Work, schedule, job, course, busy, other, commitment, life, family, hour | Time, lack, constraint, enough, available, manage, find, full, limit, free | Internet, lecture, watch, connect, video, long, computer, language, understand, English |

| Relative prevalence in first experiment | |||

| Individualist countries, % | 31 | 42 | 27 |

| Balanced countries, % | 25 | 42 | 33 |

| Collectivist countries, % | 22 | 38 | 40 |

| Relative prevalence in second experiment | |||

| Individualist countries, % | 28 | 40 | 32 |

| Balanced countries, % | 19 | 37 | 44 |

| Collectivist countries, % | 19 | 35 | 46 |

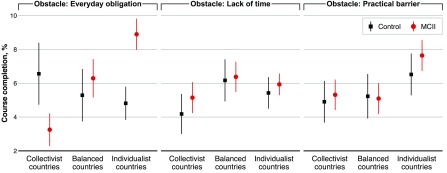

We evaluated the effect of MCII in each cultural context for each type of obstacle in the first experiment (experiment 2 yielded similar trends but was limited by its smaller sample size due to its two additional experimental conditions). We found that MCII was effective in individualist countries only if the obstacle concerned an everyday obligation (Fig. 2). In this case, MCII increased course completion by 78% relative to the control condition (b = 0.039, z = 2.93, P = 0.003). By contrast, MCII did not raise course completion in individualist countries for any other obstacle type (Ps > 0.44). We detected no statistically significant effects of MCII in other cultural contexts for any obstacle type (Ps > 0.094). There was only an unexpected negative trend in completion due to MCII among participants in collectivist countries who faced obstacles concerning everyday obligations (b = −0.035, z = −1.67, P = 0.094), discussed below. The key finding is that the primary beneficiaries of MCII were members of individualist cultures whose primary obstacle seemed to reflect an obligation that was controllable as it could be predicted and surmounted by an agentic self.

Fig. 2.

MCII’s effect is conditional on the type of learners’ stated obstacle. Course completion outcomes in the first experiment examined by obstacle type and cultural context (n = 9,619). Three obstacle types were identified using natural language processing (latent Dirichlet allocation topic modeling) of learners’ stated obstacles. Error bars represent ±1 SE.

Discussion

This research establishes that MCII can be implemented at scale for practically zero cost and still be effective for thousands of learners. The intervention was delivered as an online activity that took fewer than 8 min to complete, but its effects were substantial. Course completion increased by 32% (experiment 1) and 15% (experiment 2) for members of individualist nations in general and by 78% for those whose obstacles took the form of everyday obligations (experiment 1). This work demonstrates the potential of MCII to support goal pursuit at scale in educational settings. It may also be effective in other settings that call for self-discipline and sustained engagement, such as in organizational and health contexts. This research also shows that psychological interventions, although powerful, can be conditional in their effects. Their impact is moderated by cultural and situational forces. Benefits of MCII depended on a cultural context of individualism and emerged primarily for everyday obligations amenable to if–then planning.

As values and beliefs vary by culture, it is no simple matter to translate an intervention developed in one culture for another. Prior work shows that the benefits of II depend on a commitment to form and enact if–then plans (40). We expected that this element of MCII would appeal primarily to the analytic and agentic cognitive style prevalent in individualist cultures, where people rely more heavily on rules of formal logic to guide their thinking and behavior (37). If–then plans presuppose a degree of personal choice to act and react, an assumption that resonates more in individualist cultures than collectivist ones (36). If–then plans may also be more difficult to enact in cultures where many obstacles involve spontaneous and uncontrollable opportunities and obligations. Our results were consistent with many of these cultural differences: Compared with members of individualist nations, members of collectivist nations reported fewer obstacles that involved everyday (i.e., controllable) obligations (Table S2); they perceived if–then plans to oversimplify the complexity and uncertainty of life; and they were more likely to refuse to form if–then plans in both experiments. These culturally rooted reservations to forming if–then plans are likely to have undermined the efficacy of MCII, rendering it not only ineffective but even counterproductive. MCII yielded a negative trend for members of collectivist nations who reported obstacles related to everyday obligations, the very opposite of the pattern observed in individualist nations. It is possible that an adapted II activity, in which if–then plans are more fluid and tied to social accountability, might prove more resonant and effective in collectivist cultures.

Another contribution of this research is that it disentangles the two components of MCII relative to a control condition. In individualist cultures, MC and II alone did not increase course completion relative to the control condition. In combination, however, these two components catalyzed one another’s influence to yield a large benefit. There was also a trend in collectivist nations for MC alone to increase course completion relative to the control condition. Although speculative, one possibility is that the open-ended format of the MC activity allowed members of collectivist cultures to integrate the individualistic goal of completing all lectures with collective values, for instance, by articulating ways in which completing the course would help their family. In fact, MC has been shown to help people find integrative solutions in interpersonal bargaining (41). MC may therefore help members in collectivist cultures by energizing goal pursuit while at the same time providing sufficient latitude to think holistically about their goals. This latitude may be constricted with the addition of the II component.

Beyond culture, the type of obstacle that people anticipated moderated the effect of MCII. Natural language processing of an abundance of textual data revealed three types of obstacles reported by participants: everyday obligations, a lack of time, and practical constraints such as Internet connectivity. MCII should raise goal attainment most for surmountable and predictable obstacles (19). Consistent with this notion, MCII had no effect when learners cited a shortage of time and practical constraints as their primary obstacles. These leave relatively less freedom for adaptive solutions under the individual’s control. However, MCII had a strong effect when learners cited everyday obligations as the primary obstacle. Everyday obligations can be anticipated, planned for, and creatively adapted to. Moreover, the very regularity of such obstacles would contribute to the effectiveness of II, as they would repeatedly cue the adaptive actions that learners generate in their if–then plans (26).

This research establishes that MCII can be implemented at scale to support goal pursuit in a population of adult learners in online global learning environments. It also establishes two sources of heterogeneity in its effectiveness that are consistent with the literatures in self-regulation and cultural psychology. Although a culture’s level of collectivism–individualism is associated with other variables, such as economic prosperity, English proficiency, and other cultural differences, we evaluated several potential confounding variables and found that none of them consistently moderated the effect of MCII, save one. The exception was Inglehart’s distinction between cultures that value self-expression versus survival (42). However, this distinction is both conceptually similar to collectivism–individualism and highly correlated with it. Moreover, a stepwise regression analysis indicated that the collectivism–individualism dimension best explained the heterogeneity in our data (SI Supporting Analyses).

Our findings highlight the need to adapt self-regulation strategies to the cultural context. Members of different cultures responded divergently to seemingly minor differences in the intervention activity. The results not only suggest that the intervention taps into powerful motivational processes, but that culture can imbue even small details with important meanings. Self-regulation activities may need to be changed in light of the different cultural frameworks in which they are interpreted. In collectivist cultures, it may be important to avoid if–then contingency plans that oversimplify the complexity of socially interdependent situations. Moreover, it may be important to elicit goals congruent with the cultural context: Members of collectivist cultures might benefit from MCII if the goal is tied to collectivist values (e.g., helping their family), whereas members of individualist cultures might benefit if the goal is tied to individualist values, as in the present studies. One way to accomplish this may be to use the recently refined instructions for MCII (see refs. 18 and 43), which permit participants to flexibly define their own goals. The new Wish Outcome Obstacle Plan instructions prompt participants to generate a wish or goal of their own choosing that they deem attainable before proceeding to the MC and II steps.

Throughout the world, millions of people enroll in affordable education programs, eager to expand their horizon. Educational opportunity is growing rapidly as more people can gain access to high-quality course content online from even remote regions of the world. In a dynamic and technology-driven economy, the flexible educational opportunities provided through online learning will prove increasingly important for people to acquire new skills throughout their life. However, too many people fail to achieve their educational goals. This research shows that brief but culturally attuned practices can help people throughout the world take advantage of new educational opportunities. Not only can educational content be made to reach vast numbers of learners, but so can the self-regulatory support needed for them to succeed.

Materials and Methods

Cross-Cultural Survey.

The survey was administered through Amazon Mechanical Turk. We recruited 367 respondents located in either the United States or India. We excluded 49 respondents who did not pass basic attention checks, two who reported growing up outside of the United States or India, and 121 who had not taken an online course in the last 12 mo. The final sample included 195 respondents: 69% male; 12% aged 18–24, 63% aged 25–34, 17% aged 35–44, and 8% aged over 44. Respondents did not differ between the two countries in terms of gender, age, and the number of online courses they had taken (Ps > 0.50). Complete survey questions are available in SI Survey Questions. Statistical comparisons were conducted using t tests for normally distributed variables and Kruskal–Wallis χ2 tests for skewed variables. Respondents provided informed consent at the start of the survey. The study protocol was approved by Stanford University’s institutional review board (IRB).

Field Experiments.

We conducted two randomized controlled experiments in distinct courses offered through the two leading MOOC platforms, Coursera and Open edX. Participants were enrolled in a free online course on topics in business (experiment 1) or computer science (experiment 2). They were recruited via email to participate in the experiment, which was presented as an optional preparatory activity. Recruitment occurred either in the weeks before the start of the course (experiment 1) or right after the course began (experiment 2). The final sample encompassed 9,619 learners from 86 countries in experiment 1 and 8,344 learners from 87 countries in experiment 2 (SI Materials and Methods, for details on pretreatment exclusion criteria). Demographic information beyond geographic location was not collected, but the sample is expected to contain a majority of educated adults in full-time employment, based on prior work in similar courses (3, 7). The study protocol was approved by Stanford University’s IRB. Participants were informed at the time of enrollment that the course was used for educational research; informed consent was not required as the IRB determined that this study was exempt.

All participants reported their likelihood (7-point scale) and the importance (5-point scale) of achieving the goal of “watching most of the lectures in this course.” We chose this goal because it accommodated the variety of motivations to take the course (3). Before being assigned to conditions, participants stated two positive outcomes that they associated with watching most of the lectures in the course and two obstacles that could interfere with doing so. These pretreatment responses were used as a basis for excluding participants who stated invalid outcomes or obstacles (SI Materials and Methods) as well as for adapting the intervention content. Next, participants were randomly assigned to condition (experiment 1: MCII vs. control; experiment 2: MCII, MC, II, vs. control). The MCII materials were adapted from a prior successful MCII intervention (11). For MC, participants elaborated, first, on their stated positive outcomes associated with the goal of watching most of the lectures and, second, on how their stated obstacles could interfere with this goal; they were asked to imagine both the positive outcomes and the obstacles as vividly as possible. For II, participants wrote three if–then plans, one for each specified obstacle and one related to when and where they intended to watch lectures. In experiment 2 only, “If …, then …” was prefilled in each textbox. In the control condition, participants wrote about their personal experiences that day (experiment 1), or about prior experiences with the course topic, their expectations for the course, and how much time they intended to spend on the course each week (experiment 2). For MCII, participants received the MC activity followed by the II activity. Complete instructions are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

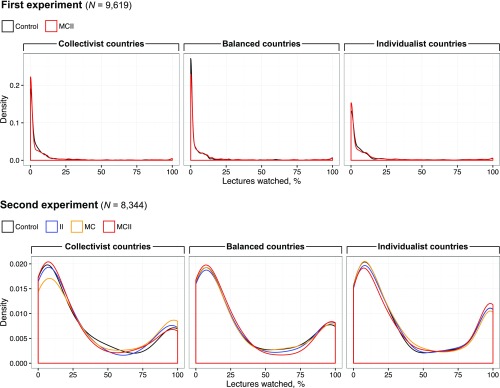

We assessed participants’ achievement in terms of course completion, a standard binary performance metric available in both studies. To complete the course, participants had to achieve a course grade above the instructor-defined threshold (70% in experiment 1; 80% in experiment 2). The course grade summarized their performance on regular course assessments and a final examination. We analyzed the intervention effects on course completion using linear probability models with robust SEs. Logistic mixed-effects models with a random effect to account for clustering by country yielded equivalent results (SI Supporting Analyses). The percentage of lectures watched in the course was also available, and although this measure showed patterns consistent with course completion, it was not amenable to analysis due to its severely skewed and multimodal distribution (SI Measures and Fig. S1). Two pretreatment covariates were included in all models to increase precision: self-reported goal importance and likelihood of attainment (mean-centered). Geographic location was determined from participants’ IP addresses using Maxmind’s GeoIP database (https://www.maxmind.com/). Cultural context was operationalized using Hofstede et al.’s individualism index (39). Thematic clusters of participants’ written descriptions of obstacles were created using topic modeling by latent Dirichlet allocation with a Gibbs sampler (six random starts of 5,000 Gibbs iterations with 4,000 burn-in and 100 thinning) (44).

Fig. S1.

Course persistence in terms of the percentage of lectures watched in two randomized experiments. The figure shows the distribution density of course persistence for each experimental condition (line color) in three cultural contexts (horizontal facets). Cultural context is defined at a national level based on the Hofstede collectivism–individualism index: collectivist countries [0, 33], balanced countries [34, 66], and individualist countries [67, 100]. In the first experiment, the density lines are visually indistinguishable due to high zero-inflation and overdispersion.

SI Materials and Methods

Participants were enrolled in a free massive open online course (MOOC) concerning either topics in organizational analysis offered on the Coursera platform (experiment 1) or introductory computer science offered on the Open EdX platform (experiment 2). In experiment 1, three waves of recruitment emails were sent to individuals who had signed up for the course in advance during the weeks leading up to the start of the course. The intervention was embedded in an online survey and presented as an optional preparatory activity. Participant recruitment stopped once the course had officially started. The survey was started 29,504 times in total, but in many instances the respondent did not advance far enough to be exposed to any experimental activities. We excluded these cases as well as many duplicate responses, where the same respondent took the survey multiple times and was exposed to different experimental conditions (for duplicate responses assigned to the same condition, only the initial response was retained). Additionally, 31 participants were excluded because their geographic location could not be determined from their IP address and another 860 from countries for which Hofstede et al.’s (39) individualism score was unavailable. The remaining dataset included 16,418 unique participants.

We further excluded participants based on a pretreatment measure, because the survey data exhibited a substantial amount of noise from invalid and unserious responses. Specifically, we excluded individuals who did not state, before assignment to condition, at least one positive outcome and one obstacle in relation to the provided course goal. This exclusion was motivated by the fact that it was critical for participants to specify a positive outcome and obstacle to complete the MCII activity. Over 6,000 individuals either wrote something irrelevant (e.g., “…,” “n/a,” “xxx,” “10,” “first”), or expressed uncertainty (e.g., “unsure,” “don’t know,” “tbd”), or indicated that they faced no obstacles (e.g., “I cannot think of any,” “there are no obstacles”). Following these exclusions, the final dataset in experiment 1 included 9,619 participants from 86 countries around the world. Importantly, all exclusions occurred prior to the experimental manipulation; thus, there was no differential selection by condition. All analyses were conducted on all remaining participants who began the experimental activities.

In the second experiment, a welcome email with a survey link was sent out at the beginning of the course to recruit participants. The same link was also available on the course website at the start of the course content. The survey was started 11,012 times in total. Exclusions were handled using the same criteria as in experiment 1, resulting in a final sample of 8,977 participants in experiment 2.

Participants were randomly assigned to conditions within the survey: in experiment 1, MCII and control (50% each), and in experiment 2, MCII, MC, II, and control (25% each). In experiment 1 only, there was a small but important difference in the control procedure for half of the participants assigned to the control condition. For these 25% of all participants in experiment 1, the pretreatment questions requesting them to state two positive outcomes and obstacles, which we used to perform consistent exclusions of invalid and unserious responses, were omitted. Consequently, all 25% of participants needed to be excluded to ensure consistency in exclusions across conditions. Importantly, there was no significant difference in course completion between the two versions of the control condition for the original sample (4.7% vs. 4.8%; X2 = 0.02, P = 0.9). This exclusion does not bias our causal inference because it occurred before exposure to the intervention activities, and it was not part of the design in experiment 2.

At the start of the intervention activity, all participants rated the likelihood and importance of achieving the goal of watching most video lectures in the course. The MCII activity, which was adapted from Duckworth et al. (11), first had participants state “two positive outcomes that [they] associate with watching most of the lectures in the course” and “two obstacles that could interfere.” Then, presented with their chosen positive outcomes, they elaborated on them in writing “by imagining each as vividly as possible.” Similarly, presented with their chosen obstacles, they elaborated on how these might interfere with watching most lectures. Participants then wrote three if–then plans, one for each specified obstacle and one relating to “when and where you intend to watch lectures.” In the control condition, to provide a writing activity similar to the one in the MCII condition, participants generated two positive outcomes and two obstacles and wrote about their recent experience and activities, ostensibly to inform the course instructor about the background of learners in the course. Below, we provide the exact instructions for each intervention activity:

-

i)

Initial instructions for all participants.

How likely or unlikely are you to watch most lectures in the course?

[Extremely/Very/Somewhat unlikely, Undecided, Somewhat/Very/Extremely likely]

How important is it to you to watch most lectures in the course?

[Not at all/Somewhat/Moderately/Very/Extremely important]

What are two positive outcomes that you associate with watching most of the lectures in this course?

First positive outcome: [text box]

Second positive outcome: [text box]

What are two obstacles that could interfere with watching most of the lectures in this course?

First obstacle: [text box]

Second obstacle: [text box]

-

ii)

Mental contrasting instructions.

Here are the two positive outcomes that you associate with watching most of the lectures in this course:

{First positive outcome}

{Second positive outcome}

Now elaborate on these outcomes in writing by imagining each as vividly as possible. What would it be like?

[Big text box]

Here are the two obstacles that you think could interfere with watching most of the lectures in this course:

{First obstacle}

{Second obstacle}

Now elaborate on these obstacles in writing by imagining each as vividly as possible. How might they interfere?

[Big text box]

-

iii)

Implementation intention instructions.

Write an if–then plan for each of your chosen obstacles like this:

“If [obstacle occurs], then I will [actionable solution].”

Obstacle 1: {First obstacle}

Write your if–then plan: [text box]

Obstacle 2: {Second obstacle}

Write your if–then plan: [text box]

Write an if–then plan for when and where you intend to watch the lecture videos: [text box]

-

iv)

Control instructions (experiment 1).

We are interested in the background of students who take this course. One way to capture this is to describe how you spend the day. Write about your experiences and activities today or yesterday.

[Big text box]

-

v)

Control instructions (experiment 2).

The following questions are about your expectations, plans for the course, and prior experience with computer science. This is an opportunity for you to specify concrete expectations and consider how you plan to manage your time. It also helps to be clear about why the course is relevant to you.

What are two things you expect from this course?

[Big text box]

What are your plans for taking this course? How much time would you like to spend on it each week?

[Big text box]

What prior experience do you have with computer science? Do you use it in school or at work? Would you like to use it more?

[Big text box]

SI Measures

The key outcome measure in both studies was course completion. Course completion was assessed based on whether a participant achieved a final course grade above 70 (experiment 1) or 80 (experiment 2) and thereby passed the course. The final course grade summarized scores on weekly assessments and a final examination.

Another available outcome measure in both experiments was course persistence, assessed by the percentage of unique lecture videos that were watched. The course comprised 95 lecture videos in experiment 1 and 33 in experiment 2 that were released in 10 and 6 weekly batches, respectively, throughout the course. However, we chose not to analyze this outcome for two reasons. First, the distribution of course persistence was right-skewed with strong zero-inflation and overdispersion in experiment 1, and u-shaped with a strong ceiling effect in experiment 2. These distributions coupled with potential country-based clustering of errors makes it challenging to perform robust statistical inference with standard methods. Second, course completion represents a higher bar than mere persistence in terms of academic achievement. For completeness, we provide plots of the persistence distribution in each condition and cultural context for both experiments (Fig. S1).

SI Survey Questions

The following questions were asked in the cross-cultural survey. Response options and input fields are indicated by square brackets.

How many online courses have you started in the last 12 mo? (please enter a number)

[text box]

What is your gender?

[Male, Female, Other]

What is your age?

[Under 13, 13–17, 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65 or older]

In which country did you grow up?

[List of country names]

This survey is about how people think about pursuing goals in education; specifically, the goal of taking an online course to learn a new topic. What motivates you when pursuing goals in education?

“I am motivated because I want to feel proud of my academic achievement.”

[Describes me extremely/very/moderately/slightly well, Does not describe me]

“I am motivated because I don't want to disappoint my family and friends with academic failures.”

[Describes me extremely/very/moderately/slightly well, Does not describe me]

Suppose you found an online course and you are highly motivated to take it. You would like to earn a good grade, but you are facing some obstacles. What obstacles, if any, would you face inside or outside of the course to achieve this goal? List as many or as few obstacles as you can think of. Try writing them down in order of importance starting with the most important.

Obstacle 1: [text box]

Obstacle 2: [text box]

Obstacle 3: [text box]

Obstacle 4: [text box]

Obstacle 5: [text box]

Obstacle 6: [text box]

Obstacle 7: [text box]

Which approach are you most likely to take when facing an obstacle? Select all that apply.

[ ] I plan future actions by identifying a specific situation and planning my response; I tell myself “If I am in situation X, then I will do Y to reach my goal.”

[ ] I get social support by asking people close to me to help me find ways to overcome the obstacle.

[ ] I seek social accountability by asking people who are close to me to monitor my progress and make me feel guilty if I don't make progress toward the goal.

Some people try to overcome obstacles by making if–then plans. For example, someone who wants to complete an online course might make the following plans:

IF I feel too tired in the evening, THEN I will drink tea to get energized and continue the course.

IF the Internet is too slow to watch lecture videos, THEN I will restart the router and try again.

If–then plans can be helpful because they provide structure by specifying what to do in a given situation.

However, if–then plans may be unrealistic because they oversimplify the situation by ignoring other obligations and unexpected events.

How much, if at all, do you think if–then plans are oversimplifying the situation?

[Extremely/Very much/Moderately/Slightly/Not at all oversimplifying]

When you aim to achieve an important goal and an obstacle comes up, how likely or unlikely are you to ask for help from people who are close to you (family, friends)?

[Extremely/Very/Somewhat likely, Neither likely nor unlikely, Somewhat/Very/Extremely unlikely]

SI Supporting Analyses

Modeling Collectivism–Individualism as a Continuous Variable.

In our analysis of heterogeneous treatment effects, we discretized the collectivism–individualism (IC) dimension to compare effects in three cultural contexts. We opted for this approach over modeling IC as a continuous variable, because we did not want to assume a linear relationship between IC and the outcome within each condition. Notably, the discrete analysis approach retains a high level of statistical power (45). Nonetheless, we repeated the main analyses with continuous IC and found consistent results.

As in the main analysis, we fitted a linear probability model with robust SEs and two covariates: self-reported goal importance and likelihood of goal attainment, both mean-centered. The model also included one (experiment 1: MCII) or three (experiment 2: MC, II, MCII) dummy-coded treatment indicator(s), continuous IC (normalized), and their interaction term(s). As expected from the findings of the main analysis, we found a significant MCII-by-IC interaction (experiment 1: b = 0.01, z = 2.07, P = 0.038; experiment 2: b = 0.026, z = 2.01, P = 0.045). In experiment 2, consistent with the results from the main analysis, the MC-by-IC interaction was marginal (b = −0.024, z = −1.80, P = 0.071). Moreover, among participants in experiment 1 whose primary obstacle was an everyday obligation, the MCII-by-IC interaction effect was particularly strong (b = 0.028, z = 2.98, P = 0.003). Thus, the findings are robust to modeling IC continuously.

Robustness to Alternative Operationalization of Culture.

We used Hofstede’s IC dimension to investigate cultural heterogeneity in the effects of MCII. We chose this measure over other conceptually similar ones for several reasons. First, it is one of the most established and widely used measures of IC in cultural psychology. Second, country-level data are available for 94 countries around the world. Third, the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample underlying the IC scores (originally a survey of IBM employees globally) resemble the general makeup of MOOC participants—employed and educated people aged between 20 and 50. This is especially true in the context of the two course topics featured in the present research: computer science and business (organizational analysis).

After finalizing the main analyses using Hofstede’s IC dimension as planned, we examined several other measures of national culture on an exploratory basis. We considered the following measures (provided in parentheses are the correlation, r, with Hofstede IC with P value and the number of countries, n, for which both measures were available): Hofstede’s (39) dimensions of power distance (PDI) (r = −0.62, P < 0.001, n = 75), indulgence–restraint (IND) (r = 0.18, P = 0.11, n = 76), masculinity–femininity (MAS) (r = 0.09, P = 0.44, n = 75), uncertainty avoidance (UAI) (r = −0.19, P = 0.11, n = 75), and long-term vs. short-term orientation (LTO) (r = 0.17, P = 0.15, n = 77); Gelfand’s (46) tightness–looseness dimension (TIL) (r = −0.37, P = 0.038, n = 31); and Inglehart’s (42) dimensions of traditional vs. secular-rational values (TSR) (r = 0.47, P < 0.001, n = 77) and survival vs. self-expression values (SSE) (r = 0.58, P < 0.001, n = 77). According to Inglehart and Welzel (47), the TSR and SSE dimensions explain over 70% of variation in world values as measured by the World Values Survey.

Our analyses indicate that, of these eight other country-level dimensions of culture, only one consistently moderated the effect of MCII in both experiments. The one significant moderator was SSE, the degree to which a society values environmental protection, immigration, diversity, and broad-based political participation, which is both conceptually similar to IC (48) and highly correlated with IC (r = 0.58, P < 0.001). Nevertheless, we found that IC provided a better model fit to explain the heterogeneity in treatment effects than SSE, based on stepwise regression analysis.

We arrived at this conclusion using the following method: We systematically tested whether any of the eight other cultural measures moderated the treatment effect in each experiment. We fit a linear probability model with robust SEs with the following predictors: condition, culture, culture-by-condition, and our two self-reported covariates (both mean-centered). In experiment 1, the MCII-by-culture interaction was significant for Hofstede’s IC, and Inglehart’s SSE, and Gelfand’s TIL (|zs| > 2.06, Ps < 0.039). In experiment 2, the MCII-by-culture interaction was significant for Hofstede’s IC and PDI, and Inglehart’s SSE (|zs| > 2.00, Ps < 0.045). Other cultural measures did not yield statistically significant interaction terms. We then evaluated which of these cultural measures best explained the heterogeneity in treatment effects using stepwise regression. As a regression that estimates interaction terms for all cultural variables at once raises problems of multicollinearity that can render results unreliable, we instead systematically compared different regression models. We selected the one with the best fit using stepwise model selection based on Akaike information criterion (AIC). AIC estimates the quality of each model relative to each of the other models, based on the likelihood function and the number of estimated parameters. We started out with a linear model predicting course completion with the following predictors: condition indicator (MCII, plus MC and II in experiment 2), normalized culture variables that were found to moderate the treatment effect (experiment 1: IC, SSE; experiment 2: IC, SSE, PDI), all condition-by-culture interactions, and the two self-report covariates (both mean-centered). In the stepwise selection procedure, any number of terms may be removed from the model. We found that IC was selected over all other moderators in both experiments. Note that TIL was a significant moderator in experiment 1, but no TIL scores were available for over one-half of the countries in our dataset. We therefore first ran stepwise regression for IC and SSE to see which one was selected in the dataset with 77 countries. In a second step, we fitted a model with IC, which was selected in the first step, and TIL using the reduced dataset with 33 countries for which both IC and TIL scores were available. Here, we found that neither IC nor TIL was a significant moderator in the reduced dataset (Ps > 0.068).

Economic and Other Country-Level Sources of Heterogeneity.

The cultural dimension of IC is not independent of other country-level variables such as economic prosperity, technological development, democracy, and English proficiency. In fact, individualistic countries also tend to be wealthy in terms of their (log) gross national income per capita (logGNI; r = 0.62) (The World Bank, 2015; World Development Indicators; data retrieved from data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD), technologically progressive in terms of the Information and Communication Technology Development Index (IDI) (r = 0.63) (International Telecommunication Union, 2016; Measuring the Information Society Report; data retrieved from www.itu.int/net4/ITU-D/idi/2016/), respectful of political rights and civil liberties in terms of the Freedom House Aggregate Score (FHS) (r = 0.56) (Freedom House, 2016; Freedom in the World; data retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/), and proficient in English in terms of the EF Education First English Proficiency Index (EPI) (r = 0.68) (EF Education First, 2016; EF English Proficiency Index; data retrieved from www.ef.edu/epi/). As the EF EPI does not provide data for English-speaking countries, we manually imputed the highest possible value for these countries. We tested whether these country-level variables also moderated the effect of MCII on completion and found that none of them did so consistently in both experiments.

We fitted a linear probability model with robust SEs with the following predictors: a condition indicator, one of the continuous country-level variables (normalized), the condition-by-variables interaction, and our two self-report covariates (both mean-centered). Despite the strong correlation with IC, none of the four variables yielded a significant interaction term in experiment 1 (zs < 1.39, P > 0.16). In experiment 2, we did however find significant MCII-by-logGNI (z = 2.18, P = 0.029) and MCII-by-IDI (z = 2.15, P = 0.032) interactions in separate models. We found no significant interactions with FHS or EPI in experiment 2 (z < 1.70, P > 0.09). Thus, we found some evidence that MCII is more effective in wealthy and technologically progressive countries, but only in one of two experiments. Moreover, the exploratory and post hoc nature of these analyses raises the possibility that this result arose by chance, in contrast to the role of IC, which was specified ex ante.

Next, we evaluated which country-level measure best explains the data using stepwise regression, as we did for the different cultural measures above. We fitted a linear model predicting course completion with the following predictors: condition indicator (MCII, plus MC and II in experiment 2), normalized continuous variables that were significant moderators (IC, IDI, logGNI), the condition-by-variable interactions, and the two self-report covariates (both mean-centered). We found that the selected model in both experiments included the condition-by-IC interaction term but not any other condition interactions. This suggests that IC explains the heterogeneity in treatment effects better than several other country-level variables.

Another potential source of heterogeneity is religious traditions. Inglehart and Welzel have argued that countries can be grouped by religious traditions due to historical path dependencies (47). The Inglehart–Welzel cultural map of the world identifies nine country clusters: Protestant Europe, Catholic Europe, Confucian, Orthodox, African-Islamic, Baltic, Latin America, South Asia, and English Speaking (World Values Survey, 2015; Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map Wave 6; data retrieved from www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp). This map is defined by the TSR and SSE dimensions, which explain over 70% of variation in world values as measured by the World Values Survey. We evaluated MCII (plus MC and II in experiment 2) treatment effects within each cluster of countries separately in each experiment. The only cluster that yielded a significant effect of MCII was the English-Speaking cluster, which included Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. This result is unsurprising as all of these countries score highly on Hofstede’s IC dimension (specifically, between 70 and 91). Moreover, our pattern of results does not appear to be related to English proficiency per se. As reported above, country-level English proficiency did not moderate treatment effects consistently. In summary, we have explored a number of alternative country-level and cross-country variables associated with IC. The results continue to suggest that IC is the driving source of heterogeneity in the effects of MCII across cultures.

Accounting for Country-Level and Religious Clustering.

An underlying statistical assumption of our main analyses is that participants are independent and identically distributed. However, participants are clustered based on the country in which they are located, and we use country-level measures of culture to identify heterogeneous treatment effects. To ensure the robustness of our main results when accounting for country-level clustering, we repeated the main analyses using a logistic mixed-effects model. We modeled participant country as a random effect to account for country-level variation. As before, we regressed course completion (binary) on the treatment indicator(s) and two self-reported covariates: goal importance and likelihood of goal attainment (both mean-centered). The results in both studies were robust to this alternative modeling approach; in fact, we found even larger effects than before.

To summarize, although there were no worldwide main effects of MCII, MC, or II, the results trended in a positive direction (experiment 1: z = 1.60, P = 0.110; experiment 2: z < 1.56, P > 0.121), and this was because the effects of MCII varied by cultural context. Members of individualist cultures were 35% (experiment 1: z = 2.22, P = 0.026) and 22% (experiment 2: z = 2.35, P = 0.019) more likely to complete the course following MCII relative to the control condition. In contrast, MCII and its individual components did not cause significant improvement in other cultural contexts (zs < 1.83, Ps > 0.068), although we once again observed a trend for members of collectivist cultures to benefit from MC alone (z = 1.83, P = 0.068). Finally, as discussed in the main text, we evaluated the effects of MCII by the type of obstacle in experiment 1. No effects of MCII were observed if the obstacle involved a practical barrier or a lack of time (zs < 0.72, Ps > 0.47). By contrast, positive effects of MCII were observed for obstacles referring to everyday obligations, such that completion rates for members of individualist cultures rose by 89% (z = 2.62, P = 0.009).

Beyond clustering at the country level, we examined another source of interdependence. Individual countries are not independent entities, especially with regards to cultural variation. Inglehart and Welzel (47) have argued that due to historical path dependencies, individual countries can be clustered by religious traditions. In its most recent version, the Inglehart–Welzel cultural map of the world identifies nine clusters of countries: Protestant Europe, Catholic Europe, Confucian, Orthodox, African-Islamic, Baltic, Latin America, South Asia, and English Speaking (World Values Survey, 2015; Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map Wave 6; data retrieved from www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp). We repeated the analysis as described above except this time we nested countries under the 9 cultural regions (plus a 10th group of countries that were not classified) by including two random effects, one for cultural region and one for country-by-region. This analysis yielded qualitatively identical results to those reported in our main analyses.

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback. This research was supported by a Computational Social Science Fellowship awarded to R.F.K. by Stanford's Institute for Research in the Social Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1611898114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kena G, et al. 2015. The Condition of Education 2015 (US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Washington, DC), NCES 2015-144, pp 234–237.

- 2.Shah D. 2015 MOOCs in 2015: Breaking down the numbers. EdSurge. Available at https://www.edsurge.com/news/2015-12-28-moocs-in-2015-breaking-down-the-numbers. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- 3.Kizilcec RF, Schneider E. Motivation as a lens to understand online learners: Toward data-driven design with the OLEI scale. ACM Trans Comput Hum Interact. 2015;22(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldrop MM. Online learning: Campus 2.0. Nature. 2013;495(7440):160–163. doi: 10.1038/495160a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kizilcec RF, Piech C, Schneider E. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, LAK 2013, Leuven, Belgium. ACM; New York: 2013. Deconstructing disengagement: Analyzing learner subpopulations in massive open online courses; pp. 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reich J. 2014 MOOC completion and retention in the context of student intent. Educause Review Online. Available at er.educause.edu/articles/2014/12/mooc-completion-and-retention-in-the-context-of-student-intent. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- 7.Kizilcec RF, Halawa S. Proceedings of the Second ACM Conference on Learning at Scale. ACM; New York: 2015. Attrition and achievement gaps in online learning; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kizilcec RF, Pérez-Sanagustín M, Maldonado JJ. Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in massive open online courses. Comput Educ. 2017;104:18–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):248–287. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pintrich PR, de Groot EV. Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. J Educ Psychol. 1990;82(1):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duckworth AL, Grant H, Loew B, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Self‐regulation strategies improve self‐discipline in adolescents: Benefits of mental contrasting and implementation intentions. Educ Psychol. 2011;31(1):17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72(2):271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schunk DH, Zimmerman BJ. Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance: Issues and Educational Applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lajoie S, Azevedo R. Teaching and learning in technology-rich environments. Handb Educ Psychol. 2006;2:803–821. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reich J. Education research. Rebooting MOOC research. Science. 2015;347(6217):34–35. doi: 10.1126/science.1261627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Goal setting and goal striving. In: Tesser A, Schwarz N, editors. Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Intraindividual Processes. Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2001. pp. 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Self-regulation: Principles and tools. In: Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM, editors. Self-Regulation in Adolescence. Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 2015. pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oettingen G. Future thought and behaviour change. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2012;23(1):1–63. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oettingen G, Pak H, Schnetter K. Self-regulation of goal setting: Turning free fantasies about the future into binding goals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(5):736–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gollwitzer A, Oettingen G, Kirby TA, Duckworth AL, Mayer D. Mental contrasting facilitates academic performance in school children. Motiv Emot. 2011;35(4):403–412. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oettingen G, Mayer D, Thorpe J. Self-regulation of commitment to reduce cigarette consumption: Mental contrasting of future with reality. Psychol Health. 2010;25(8):961–977. doi: 10.1080/08870440903079448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kappes A, Oettingen G. The emergence of goal pursuit: Mental contrasting connects future and reality. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2014;54:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sevincer AT, Busatta PD, Oettingen G. Mental contrasting and transfer of energization. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014;40(2):139–152. doi: 10.1177/0146167213507088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gollwitzer PM, Brandstätter V. Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(1):186–199. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orbeil S, Hodgldns S, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and the theory of planned behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997;23(9):945–954. doi: 10.1177/0146167297239004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. 1999;54(7):493–503. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta‐analysis of effects and processes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;38:69–119. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adriaanse M, et al. When planning is not enough: Fighting unhealthy snacking habits by mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII) Eur J Soc Psychol. 2010;40(7):1277–1293. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christiansen S, Oettingen G, Dahme B, Klinger R. A short goal-pursuit intervention to improve physical capacity: A randomized clinical trial in chronic back pain patients. Pain. 2010;149(3):444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duckworth AL, Kirby T, Gollwitzer A, Oettingen G. From fantasy to action: Mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII) improves academic performance in children. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2013;4(6):745–753. doi: 10.1177/1948550613476307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gawrilow C, Morgenroth K, Schultz R, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Mental contrasting with implementation intentions enhances self-regulation of goal pursuit in schoolchildren at risk for ADHD. Motiv Emot. 2012;37(1):134–145. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirk D, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Promoting integrative bargaining: Mental contrasting with implementation intentions. Int J Confl Manage. 2013;24(2):148–165. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oettingen G, Kappes HB, Guttenberg KB, Gollwitzer PM. Self-regulation of time management: Mental contrasting with implementation intentions. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2015;45:218–229. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stadler G, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Physical activity in women: Effects of a self-regulation intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stadler G, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Intervention effects of information and self-regulation on eating fruits and vegetables over two years. Health Psychol. 2010;29(3):274–283. doi: 10.1037/a0018644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98(2):224–253. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nisbett RE, Peng K, Choi I, Norenzayan A. Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychol Rev. 2001;108(2):291–310. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oettingen G. Culture and future thought. Cult Psychol. 1997;3(3):353–381. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. 3rd Ed McGraw-Hill; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Achtziger A, Bayer UC, Gollwitzer PM. Committing to implementation intentions: Attention and memory effects for selected situational cues. Motiv Emot. 2012;36(3):287–300. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirk D, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Mental contrasting promotes integrative bargaining. Int J Confl Manage. 2011;22(4):324–341. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inglehart R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oettingen G. Rethinking Positive Thinking: Inside the New Science of Motivation. Current; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grün B, Hornik K. topicmodels : An R package for fitting topic models. J Stat Softw. 2011;40(13):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gelman A, Park DK. Splitting a predictor at the upper quarter or third and the lower quarter or third. Am Stat. 2009;63(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gelfand MJ, et al. Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science. 2011;332(6033):1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1197754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inglehart R, Welzel C. Changing mass priorities: The link between modernization and democracy. Perspect Polit. 2010;8(2):551–567. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inglehart R, Oyserman D. Individualism, autonomy and self-expression: The human development syndrome. In: Vinken H, Soeters J, Ester P, editors. Comparing Cultures: Dimensions of Culture in a Comparative Perspective. Brill; Boston: 2004. pp. 74–96. [Google Scholar]