Significance

Hospitalized patients are susceptible to serious infections that are rarely encountered by healthy people. Two of the most problematic causes are Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans, a bacterium and fungus, respectively. Both are members of our normal microbial communities, but cause significant mortality in immunocompromised individuals. The formation of biofilms—microbial communities that grow on biotic or artificial surfaces—is a common feature of these infections and presents a formidable barrier to their treatment. We show here that E. faecalis produces a small protein that is a potent inhibitor of the ability of C. albicans to form biofilms and reduces fungal virulence in several models, raising the possibility that it might be developed as an antifungal agent.

Keywords: Candida albicans, Enterococcus faecalis, biofilms, bacteriocins

Abstract

Enterococcus faecalis, a Gram-positive bacterium, and Candida albicans, a fungus, occupy overlapping niches as ubiquitous constituents of the gastrointestinal and oral microbiome. Both species also are among the most important and problematic, opportunistic nosocomial pathogens. Surprisingly, these two species antagonize each other’s virulence in both nematode infection and in vitro biofilm models. We report here the identification of the E. faecalis bacteriocin, EntV, produced from the entV (ef1097) locus, as both necessary and sufficient for the reduction of C. albicans virulence and biofilm formation through the inhibition of hyphal formation, a critical virulence trait. A synthetic version of the mature 68-aa peptide potently blocks biofilm development on solid substrates in multiple media conditions and disrupts preformed biofilms, which are resistant to current antifungal agents. EntV68 is protective in three fungal infection models at nanomolar or lower concentrations. First, nematodes treated with the peptide at 0.1 nM are completely resistant to killing by C. albicans. The peptide also protects macrophages and augments their antifungal activity. Finally, EntV68 reduces epithelial invasion, inflammation, and fungal burden in a murine model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. In all three models, the peptide greatly reduces the number of fungal cells present in the hyphal form. Despite these profound effects, EntV68 has no effect on C. albicans viability, even in the presence of significant host-mimicking stresses. These findings demonstrate that EntV has potential as an antifungal agent that targets virulence rather than viability.

Opportunistic pathogens present unique clinical challenges. Although rare or niche pathogens of immunocompetent individuals, they take advantage of breakdowns of immunological or physiological barriers to impose significant morbidity and mortality. Two such organisms are the fungus Candida albicans and the Gram-positive bacterium Enterococcus faecalis (1–3), which occupy overlapping niches in the normal mammalian microbiome, including in the gastrointestinal tract, oral cavity, and urogenital tract (2, 4). Both species are among the most common causes of sepsis in hospitalized patients (5), and they are frequently coisolated in a variety of human infections (6).

C. albicans and E. faecalis are robust biofilm-forming organisms, presenting another therapeutic complication (7, 8). C. albicans biofilms are polymorphic structures that can exceed 200 µm in depth and contain hyphal and yeast cells encased in a carbohydrate-based extracellular matrix that increases resistance to antimicrobial drugs and immune surveillance (8). Biofilms are a key factor in device-associated infections on catheters, denture materials, and other medical implants, as well as on mucosal surfaces in the oral cavity and urogenital track, and pose a significant clinical problem (7–9). Agents that specifically target biofilms would potentially be highly synergistic with existing antifungal drugs, but are not yet available.

Biofilms in nonsterile mucosal sites are usually polymicrobial, and the interaction between the resident microbes can be either antagonistic or synergistic (reviewed in refs. 10–12). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and C. albicans have an intricate relationship in which one bacterial product (phenazines) kills hyphal cells, whereas another (homoserine lactones) induces a switch to the resistant yeast form (13, 14). However, a synergistic interaction between C. albicans and either Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus gordonii increases biofilm biomass (15, 16). We previously reported antagonistic interactions between C. albicans and E. faecalis by using both a Caenorhabditis elegans model, in which a coinfection was significantly less virulent than either monomicrobial infection, and a biofilm model in which a factor secreted from E. faecalis inhibited hyphal differentiation (17).

In this work, we identity this factor as EntV, a secreted bacteriocin. A synthetic version of this peptide inhibited C. albicans hyphal morphogenesis and biofilm formation at subnanomolar concentrations. Furthermore, EntV was active against mature biofilms, shrinking their depth and biomass. Interestingly, EntV did not kill C. albicans, nor inhibit its growth, even at high concentrations. Nevertheless, EntV completely protected C. elegans from C. albicans infection, and increased fungal clearance by murine macrophages. Additionally, EntV dramatically reduced invasion and inflammation in a murine model of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), a biofilm-related infection that is common in immunocompromised patients (18). Because the rise of drug-resistant fungal infections threatens to undermine the current small arsenal of available treatments, we propose that EntV, or similar compounds, may offer a viable therapeutic alternative, either alone or in combination with existing agents.

Results

E. faecalis Supernatant Inhibits C. albicans Hyphal Morphogenesis and Biofilm Formation.

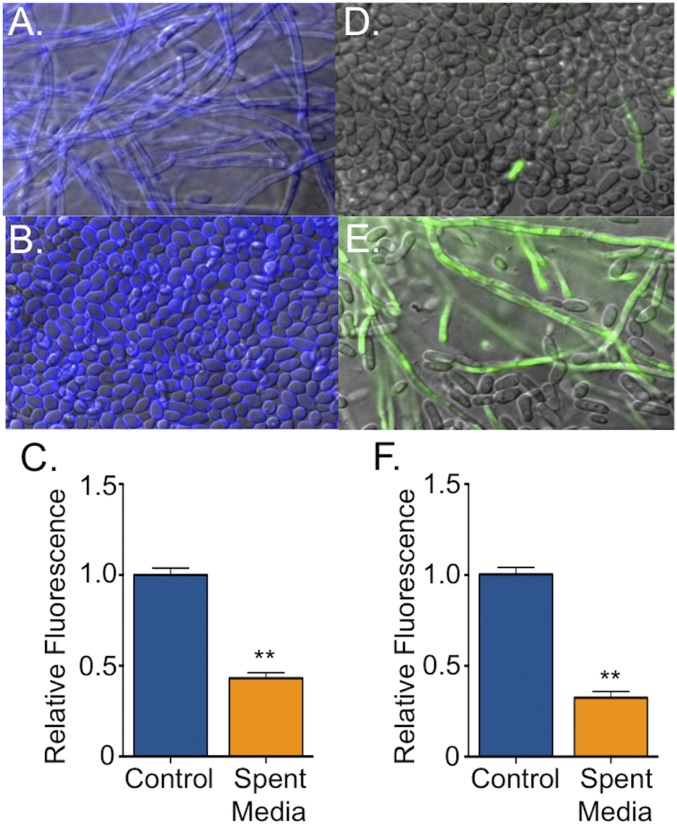

To facilitate identification of the E. faecalis inhibitor, we developed a C. albicans in vitro biofilm model in which cells are grown on a polystyrene substrate in an artificial saliva medium (YNBAS; adapted from ref. 19). This media supported robust biofilm growth, whereas supplementation with supernatant from E. faecalis cultures decreased both biofilm biomass and hyphal morphogenesis compared with biofilms grown in medium alone, as observed microscopically in biofilms stained with calcofluor white (Fig. 1 A and B) or by quantitation of biomass using the redox-reactive dye resazurin (20) (Fig. 1C). The reduction in hyphal formation was assayed by using a GFP reporter strain under the control of the hyphal-specific HWP1 gene (HWP1p::GFP) (Fig. 1 D–F) (21). A direct correlation between hyphal abundance and biofilm biomass was observed, in agreement with previous studies (22, 23).

Fig. 1.

E. faecalis supernatant inhibits C. albicans hyphal morphogenesis and biofilm formation. C. albicans biofilms grown for 24 h in YNBAS. Representative images of C. albicans (strain SC5314) biofilms in the absence (A) and presence (B) of E. faecalis supernatant and stained with calcofluor white. (C) Biofilm density was quantified by measuring resazurin fluorescence. Representative images of C. albicans hyphal reporter strain (HWP1p::GFP) in the absence (D) or presence (E) of E. faecalis supernatant. (F) Hyphal morphogenesis was quantified by measuring GFP fluorescence as a ratio to the OD600. Experiments were performed three times and analyzed by using Student’s t test (**P < 0.01).

EntV Inhibits Hyphal Morphogenesis and Biofilm Formation in C. albicans.

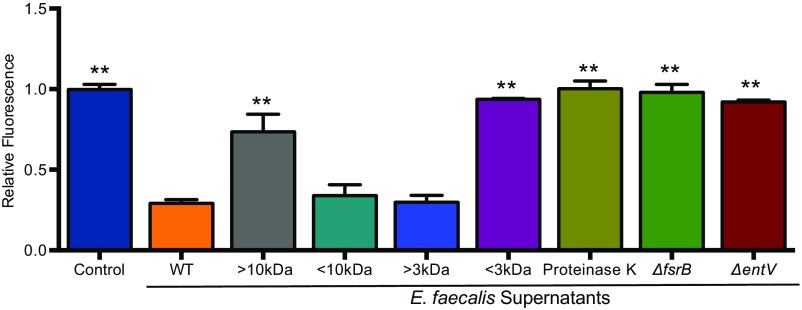

Our previous studies in the C. elegans infection model suggested that the secreted inhibitor is a heat-stable peptide, of 3–10 kDa, regulated by the Fsr two-component quorum sensing system (17). We confirmed that biofilm inhibition was mediated by a factor with similar characteristics (Fig. S1). The Fsr system regulates multiple virulence-related traits, including the secreted proteases GelE and SprE and a bacteriocin produced from the ef1097 gene (24–26). ef1097 encodes a 170-aa prepeptide, and cleavage of the secretion leader sequences results in the export of a 136-residue propeptide (EntV136) that has bactericidal activity against Gram-positive bacteria and has been referred to as enterococcin V583 and enterocin O16 (25, 27). The ef1097 gene is present in all E. faecalis strains sequenced to date (25), and we propose to name the gene product EntV, for Enterocin originally found in V583.

Fig. S1.

Characterization of inhibitory activity from E. faecalis supernatants. C. albicans (HWP1p::GFP) biofilms grown at 37 °C for 24 h in YNBAS. Hyphal morphogenesis was quantified by measuring GFP fluorescence as a ratio to the OD600. Inhibitory activity from E. faecalis supernatant was retained between 3–10 kDa after size exclusion centrifugation. A reduction of inhibitory activity was observed in supernatants treated with proteinase K and from deletion mutants of fsrB or entV. Experiments were repeated at least three times and statistically significant differences relative to treatment with the WT supernatant were calculated by using a one-way ANOVA, and are indicated by asterisks (**P < 0.01).

We tested the hypothesis that EntV is the secreted inhibitor by generating a deletion mutant. Indeed, the biofilm inhibitory activity was lost in supernatants derived from the entV mutant strain relative to those from the WT E. faecalis strain (Fig. 2A), confirming that EntV is necessary for the inhibition of biofilm formation. Inhibitory activity was restored in a complemented strain in which entV was restored to the endogenous locus (Fig. 2A). To test whether EntV136 was sufficient for the inhibitory activity, rEntV136 was produced in Escherichia coli with a hexa-histidine tag. The purified protein was functional, with an IC50 of ∼1,000 nM (Fig. 2B). Thus, EntV is both necessary and sufficient for inhibition of C. albicans biofilm formation.

Fig. 2.

EntV inhibition of hyphal morphogenesis and biofilm formation in C. albicans. (A) C. albicans SC5314 biofilms grown for 24 h in YNBAS with sterile media (M9HY) or spent supernatant from wild-type and mutant E. faecalis strains. Hyphal morphogenesis was quantified by measuring GFP fluorescence as a ratio to the OD600. The experiment was performed three times and analyzed by using one-way ANOVA (**P < 0.01). (B) Biofilms were grown with increasing concentrations of rEntV136 or sEntV68 and the IC50 calculated at 1,000 nM and 0.3 nM, respectively. (C) C. albicans was grown at 30 °C in YPD for 15 h in a 96-well plate with increasing concentrations of sEntV68, and OD600 was measured every 2 min in a microplate reader.

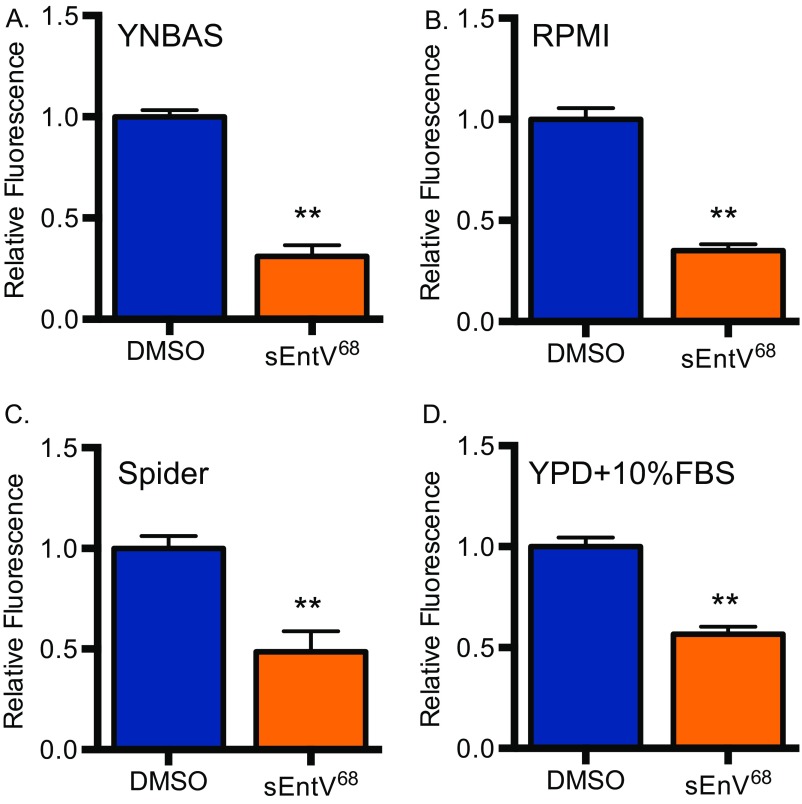

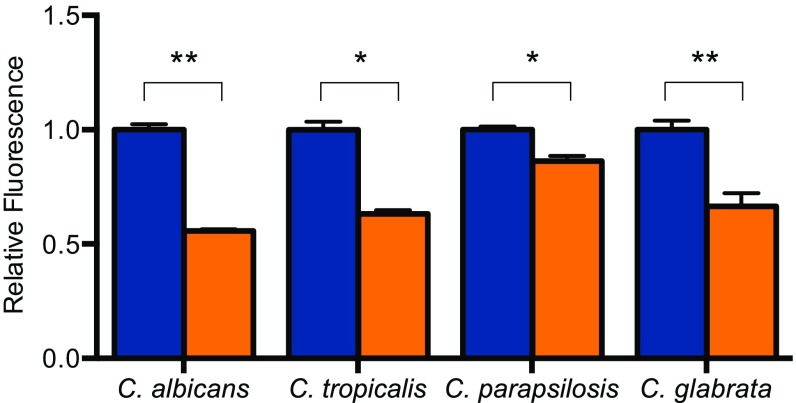

EntV136 is larger than the 3–10 kDa indicated by our preliminary characterization. Recent work (25) suggests that EntV136 is further processed in a GelE-dependent manner to a 7.2-kDa peptide encompassing the 68 carboxyl-terminal amino acids (EntV68). A predicted disulfide bond encompasses nearly the entire length of the active peptide (amino acids 4–65) and is necessary for its antibacterial activity (25, 27). Attempts to express and purify EntV68 were unsuccessful because of apparent toxicity in E. coli. As an alternative, the peptide was synthetically produced, including the disulfide bond (sEntV68). sEntV68 was 3,000-fold more effective at inhibiting biofilm formation (IC50 = 0.3 nM) than the unprocessed peptide in a variety of media conditions (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2). sEntV68 was also active against biofilms formed by other pathogenic Candida species, including C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis (Fig. S3). In contrast, EntV68 had no effect on the growth of planktonic cells at concentrations as high as 10 µM (Fig. 2C). Further, EntV68 did not alter fungal susceptibility to host-associated stresses, including oxidative, nitrosative, cell wall, and cell membrane stresses (Fig. S4). Thus, EntV is a specific inhibitor of hyphal and biofilm growth.

Fig. S2.

sEntV68 inhibitory activity in different media types. C. albicans (HWP1p::GFP) biofilms grown for 24 h at 37 °C in YNBAS (A), RPMI (B), Spider (C), or YPD (D) with 10% FBS with 0.01% DMSO (blue) or 100 nM sEntV (orange). Hyphal morphogenesis was quantified by measuring GFP fluorescence as a ratio to the OD600 for three separate experiments and statically significant differences were calculated by using a Student’s t test (**P < 0.01).

Fig. S3.

sEntV68 inhibitory activity against different Candida species. C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata biofilms grown for 24 h in RPMI (with l-glutamine and Hepes) at 37 °C for 24 h with 0.01% DMSO (blue) or 100 nM sEntV (orange). Biofilm density was quantified by measuring resazurin fluorescence for three separate experiments and statically significant differences were calculated by using a Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

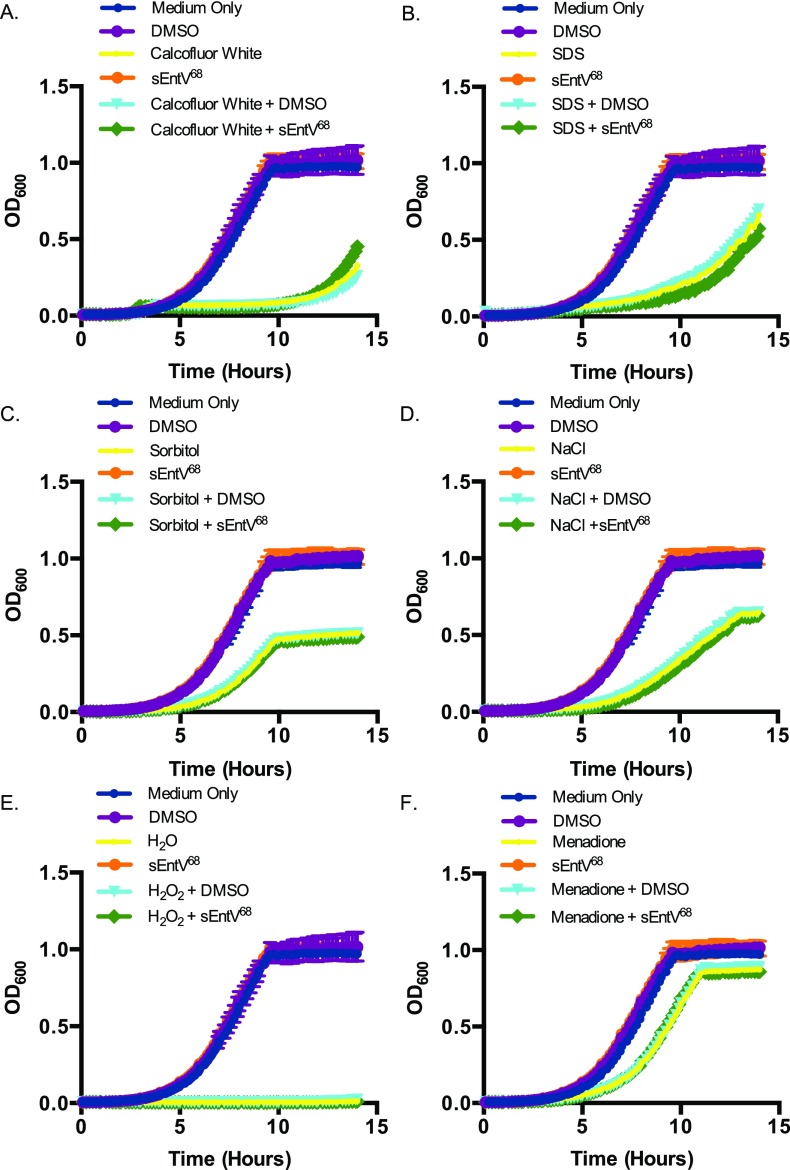

Fig. S4.

Impact of host-relevant stresses on sEntV68 activity. C. albicans (SC5314) was grown for 15 h in YPD at 30 °C with sEntV68 (100 nM) in different stress conditions: cell wall stress calcofluor white (100 μg/mL) (A) and SDS (10%) (B); cell membrane stress sorbitol (1 M) (C) and sodium chloride (1 M) (D); and oxidative stress hydrogen peroxide (5 mM) (E) and menadione (100 μM) (F) in a 96-well plate. OD600 was measured every 2 min in a microplate reader.

sEntV68 Is Active Against Mature Biofilms.

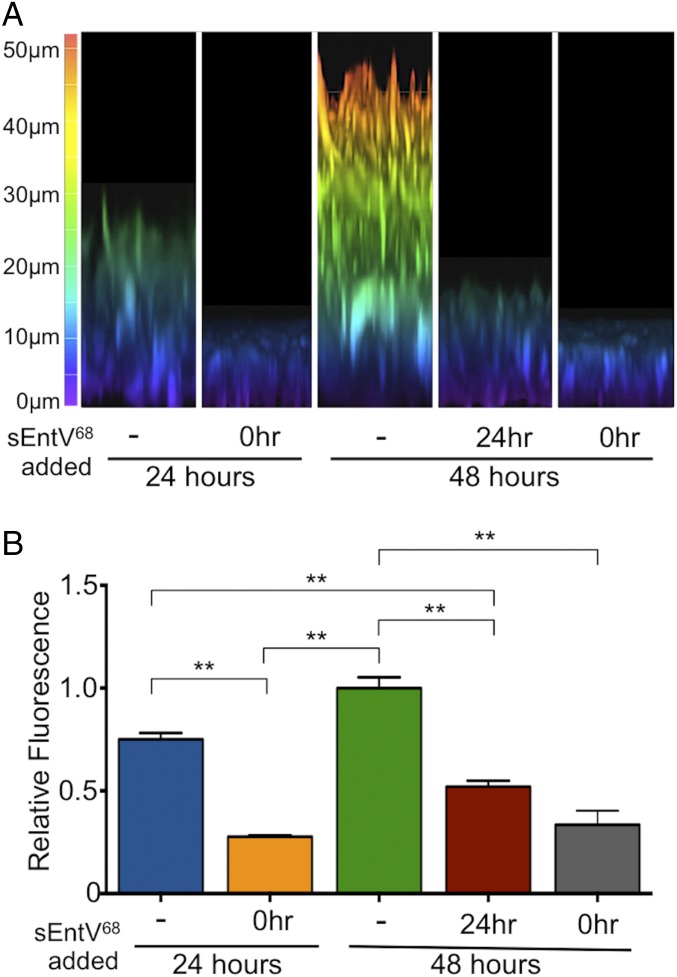

We used confocal microscopy to visualize the effect of sEntV68 on the morphology and depth of C. albicans biofilms. When grown in our nutrient-poor artificial saliva medium, control biofilms were 25–30 µm thick after 24 h, but only 5–10 µm in the presence of sEntV68, roughly the length of a C. albicans yeast cell (Fig. 3A). To ask whether sEntV68 affected preformed biofilms, we allowed them to develop for 24 h before adding the peptide. Over a subsequent 24 h, peptide-treated biofilms were reduced from ∼30 µm to ∼15 µm, whereas untreated controls grew to >50 µm (Fig. 3A), indicating that this peptide could dismantle mature biofilms. The HWP1p::GFP hyphal-specific reporter confirmed the decrease in hyphal cells and biomass following EntV68 treatment of preformed biofilms (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of sEntV68 inhibitory activity. C. albicans SC5314 biofilms were grown with 0.01% DMSO or 100 nM sEntV68 added at different time points during biofilm formation (-, not added; 0hr, added at the beginning of the experiment. (A) Representative image of 24-h and 48-h biofilms observed by confocal microscopy. (B) Hyphal morphogenesis was quantified by measuring GFP fluorescence as a ratio to the OD600 for three separate experiments (**P < 0.01).

Protection of C. elegans by sEntV68 During C. albicans Infection.

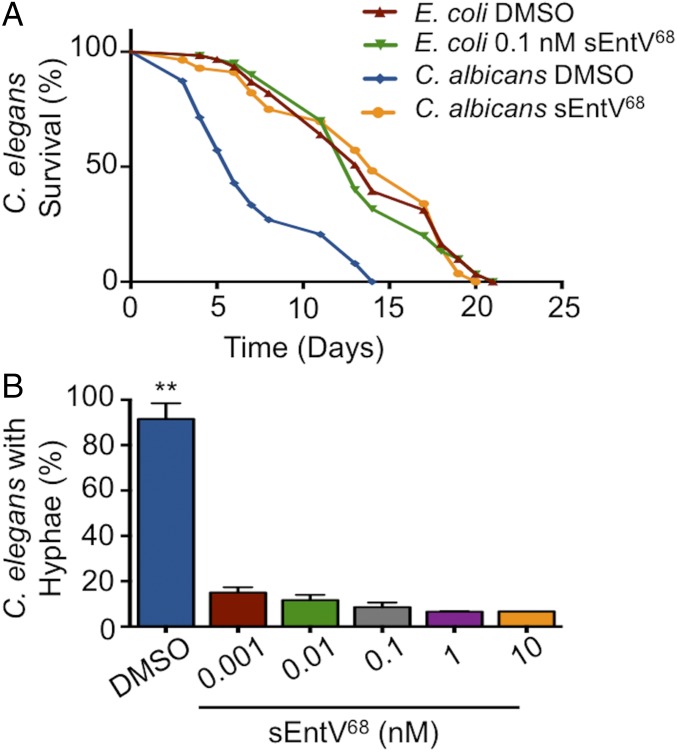

We next asked whether sEntV68 was protective in several C. albicans infection models. We first used a nematode infection system in which pathogenesis partially depends on hyphal morphogenesis, as it is in mammalian infections (28–30). The presence of sEntV68 completely abrogated C. albicans virulence in the nematodes at subnanomolar concentrations, such that the lifespan was similar to nematodes fed on nonpathogenic E. coli (Fig. 4A). At these concentrations, no apparent toxicity of sEntV68 was observed (Fig. 4A). To ask whether the virulence effect was due to morphological differences, we quantified the proportion of C. elegans in which filamentous C. albicans could be observed, and found that even 1 pM sEntV68 dramatically decreased the number of worms showing evidence of invasive fungal hyphae relative to controls (Fig. 4B). Consistent with these results, the ΔentV E. faecalis mutant was also unable to protect C. elegans from C. albicans infection (Fig. S5). Taken together, these results suggest sEntV68 is effective at protecting C. elegans during infection with C. albicans via inhibition of hyphal morphogenesis.

Fig. 4.

sEntV68 protects C. elegans from killing by C. albicans. C. elegans was exposed to C. albicans SC5314 on BHI agar or E. coli OP50 on NB agar for 2 h, then washed with sterile PBS and transferred to six-well plates containing increasing concentrations of sEntV68 or DMSO at ∼30 nematodes per well. (A) Representative data of three independent experiments where nematode viability was scored daily. (B) Nematodes were assayed for evidence of visible C. albicans filaments penetrating the cuticle after 7 d of infection (**P > 0.01).

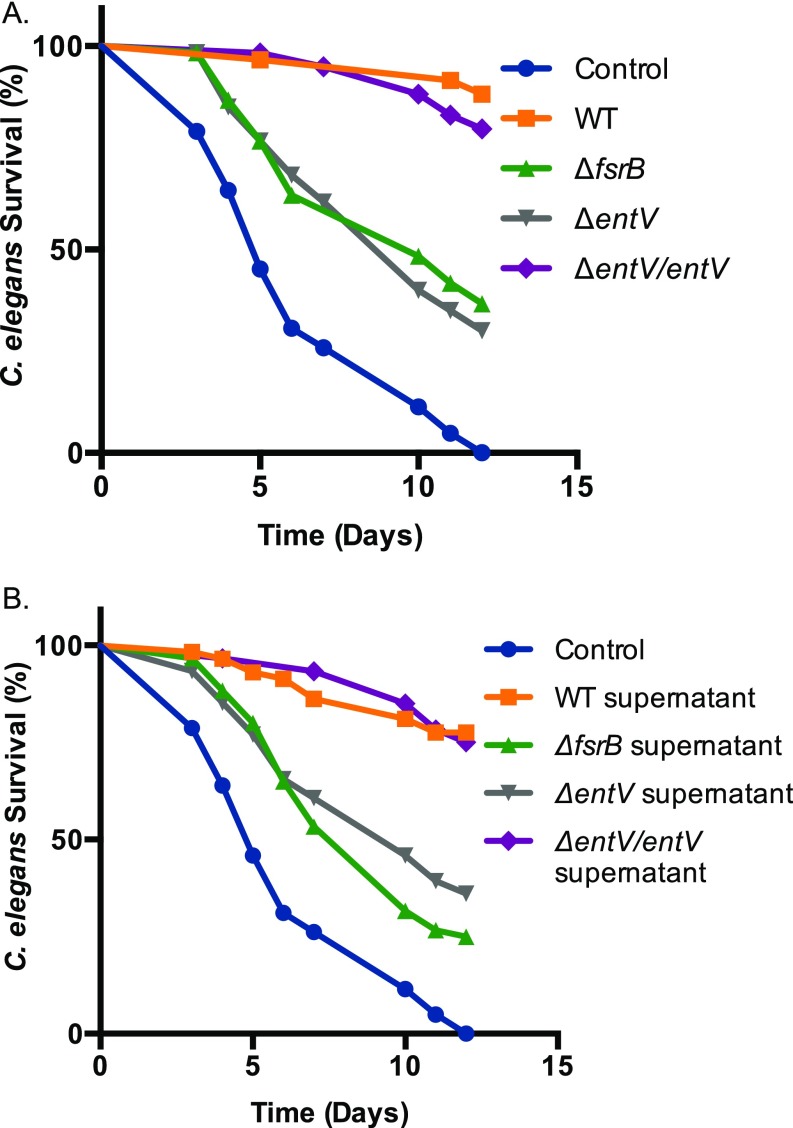

Fig. S5.

EntV inhibition of virulence and hyphal morphogenesis of C. albicans in C. elegans. (A) C. elegans was exposed to E. faecalis on BHI agar or E. coli OP50 on NG agar for 2 h, followed by exposure to C. albicans on BHI agar for 2 h then washed with sterile PBS and transferred to six-well plates at ∼30 nematodes per well. (B) C. elegans was exposed to C. albicans SC5314 on BHI agar or E. coli OP50 on NB agar for 2 h, then washed with sterile PBS and transferred to six-well plates containing 20% E. faecalis supernatants or sterile BHI media at ∼30 nematodes per well. Both graphs are representative data of three independent experiments where nematode viability was scored daily.

Protection of Murine Macrophages by sEntV68 During C. albicans Infection.

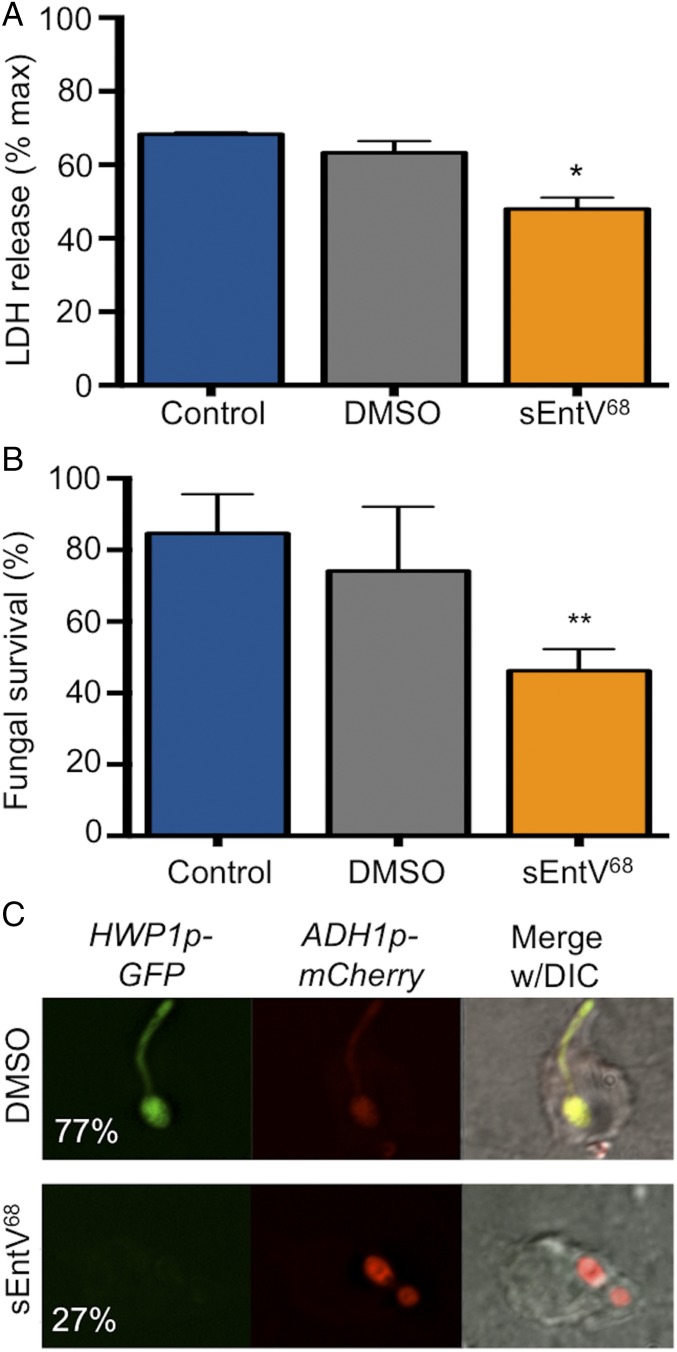

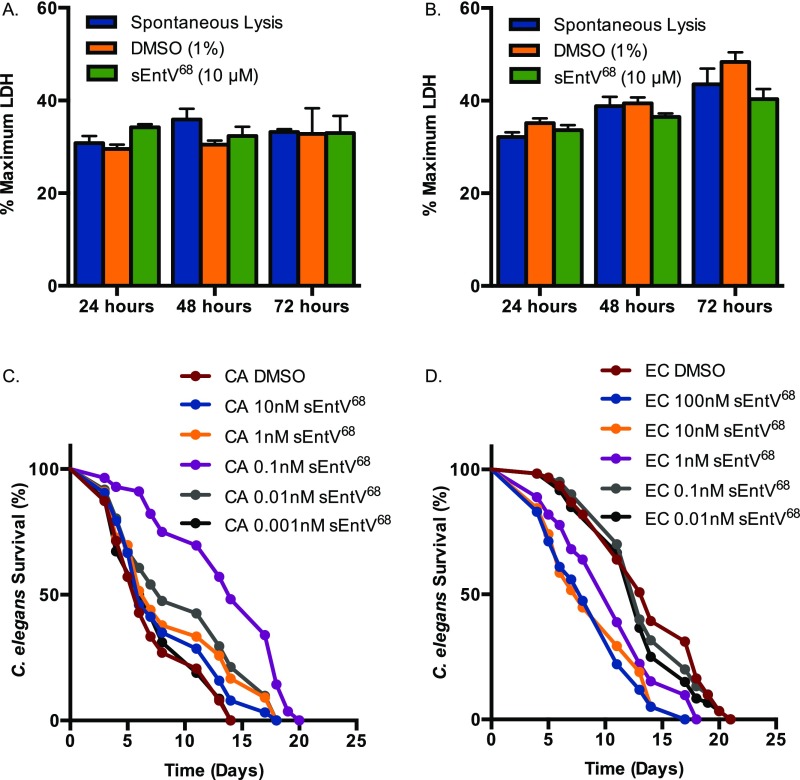

C. albicans is readily phagocytosed by murine macrophages, whereupon it activates a complex transcriptional and morphogenetic program that promotes fungal survival and results in hyphal-dependent macrophage lysis (31). Using a standard coculture system (32), we observed a significant decrease in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, a measure of macrophage membrane damage, from C. albicans-exposed cells in the presence of sEntV68 relative to our controls (Fig. 5A), indicating that the peptide reduces fungal-induced cytotoxicity. Conversely, sEntV68 potentiates the antifungal activity of the macrophage, resulting in fewer surviving fungal cells (Fig. 5B). To assess whether sEntV68 inhibits hyphal morphogenesis within macrophages, we used the HWP1p::GFP reporter strain modified to constitutively express mCherry (ADH1p::mCherry). Cells treated with sEntV68 had a decrease in hyphal growth and GFP fluorescence compared with control treated cells (Fig. 5C). No toxicity of the peptide toward macrophages or HeLa cells was observed. In contrast, some toxicity was observed in the C. elegans infection model above the protective concentration of 0.1 nM (Fig. S6). Taken together, these results indicate that sEntV68 protects murine macrophages by inhibition of C. albicans hyphal morphogenesis.

Fig. 5.

Protection of murine macrophages by sEntV68 during C. albicans infection. (A) RAW264.7 murine macrophages were incubated with C. albicans SC5314 for 4 h with or without 100 nM sEntV68. Macrophage killing was evaluated by using the LDH cell toxicity assay, and the percentage of killed macrophages was calculated. (B) C. albicans survival in murine macrophages was assessed by using the XTT cell viability assay. (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (C) RAW264.7 cells were infected with C. albicans (HWP1p::GFP, ADH1p::mCherry) for 1 h ± peptide followed by fixation and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. The percentage of hyphal cells was scored after 2 h of coculture and is given in the left image for both conditions. At least 200 cells were counted per replicate, and the experiment was repeated three times.

Fig. S6.

Activity of sEntV68 in mammalian cells and C. elegans. LDH was measured from murine macrophages (RAW 264.7) (A) and HeLa (B) exposed to 10 μM sEntV68 or 1% DMSO for up to 72 h. C. elegans was exposed to C. albicans SC5314 on BHI agar (C) or E. coli OP50 (D) on NB agar for 2 h, then washed with sterile PBS and transferred to six-well plates containing increasing concentrations of sEntV68 or DMSO at ∼30 nematodes per well. Representative data of three independent experiments where nematode viability was scored daily.

sEntV68 Reduces the Pathology Associated with OPC.

C. albicans is a normal resident of the oral microflora, but OPC is a common cause of pathology in immunocompromised individuals, notably infants, adults who are HIV+, and dental implant wearers (33–35). We used an established OPC model (36) in which steroid immunosuppressed mice were given a sublingual inoculation of C. albicans and then provided drinking water containing sEntV68 or DMSO for up to 5 d. The mice were euthanized and tongues were excised at days 3 and 5 to examine the histology and fungal burden. Control mice showed classical signs of OPC, including extensive invasion of the epithelium by fungal hyphae, disruption of the outer layers of epithelial cells, and infiltration of neutrophils (Fig. 6A). In contrast, mice that were treated with 100 nM sEntV68 had significantly reduced invasion; most fungal cells were in the yeast or pseudohyphal form, indicating that the peptide can inhibit morphological differentiation in vivo as well (Fig. 6B). To quantitate epithelial invasion, we scored the proportion of the epithelial surface infected in multiple tongues from control or sEntV68-treated mice, as recently described (37). A clear difference was apparent between treated and control animals (Fig. 6C). Hyphal cells were more abundant in control animals, which can lead to an underestimation of colony-forming units (CFUs) because of their multinucleate and adhesive nature. Thus, to assess fungal burden we quantitated fungal DNA by using quantitative PCR (qPCR) as described (38, 39); a significant decrease in tongue fungal burden was evident in peptide-treated relative to control mice (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that sEntV68 is effective in a complex mammalian infection model that simulates clinically relevant, infection conditions.

Fig. 6.

sEntV68 is protective in a murine OPC model. Immunosuppressed mice were inoculated sublingually with C. albicans SC5314 with 0.01% DMSO or 100 nM sEntV68. Water containing sEntV68 (100 nM) or vehicle (DMSO) alone was provided ad libitum. After 3 or 5 d, mice were euthanized and the tongues were excised for histological examination of DMSO control (A) or sEntV68-treated (B) mice. Red arrowheads indicate hyphal cells, and black arrowheads indicate yeast cells. (C) The percentage of the epithelial surface showing evidence of fungal invasion was calculated for control and treated tongues. (D) DNA was extracted from the tongues and the fungal burden was estimated from qPCR amplification of the 5.8S ITS2 region. Statistically significant differences were calculated by using one-way ANOVA (**P < 0.01).

Discussion

Hyphal differentiation is crucial for biofilm formation as it is for many aspects of C. albicans pathogenicity (23, 29, 30). We demonstrate here that the E. faecalis bacteriocin EntV potently inhibits biofilm growth by preventing the switch to the hyphal form. The implications of this inhibitory activity are clearly seen in the decreased virulence of C. albicans cells exposed to this peptide in C. elegans, in macrophages, and in the mouse OPC model.

EntV is a bacteriocin originally studied for its killing activity against other Gram-positive bacteria, including species of lactococci and streptococci (25, 27). The propeptide is processed into a 68-aa peptide containing a disulfide bridge that cyclizes nearly the entire protein. Between the cysteines, the structure of the mature form of EntV is predicted in silico to consist of two helical elements, separated by a flexible loop region (25, 27). The bactericidal activity of EntV is not due to lysis and there is no evidence of an immunity protein, so the mechanism remains enigmatic (25, 27). Likewise, the mechanism of the antihyphal activity is unclear, although it does not lyse fungal cells either. In fact, growth and chemical sensitivity of C. albicans cells is unaffected, even when exposed to concentrations four logs higher than the IC50. Thus, EntV exerts a true antivirulence effect on this important fungal pathogen. It has been speculated that therapeutics that target virulence might be less likely to select for resistance. In support of this idea, a small molecule also exhibiting C. albicans biofilm and hyphal morphogenesis-inhibiting properties did not induce resistance after repeated exposure (40).

In the OPC model, EntV reduced, but did not eliminate, fungal colonization. In contrast, fungal invasion of the epithelium and inflammation, which are responsible for the pathology of OPC, were almost entirely absent. Thus, in the presence of EntV, C. albicans reverts to a benign commensal interaction with the host. We have speculated that these two species might find it advantageous to suppress virulence attributes in favor of colonization (10); indeed, C. albicans promotes E. faecalis colonization in the gastrointestinal tract (41, 42). This proposal is counter to studies that suggest these species are commonly isolated together in many clinical samples (6) but this, too, might represent a coordination of behavior through sensing host weaknesses to switch cocommensal to copathogen. In support of this notion, EntV68 does not affect hyphal growth stimulated by mammalian serum, the strongest inducing factor (17) and an obvious host signal during disseminated infection. A precedent for this apparent contradiction is seen in the interaction between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa, species that are antagonistic in vitro (13, 43), but associated with significantly worse clinical outcomes when found together in several clinical settings (44, 45). It is possible that some of the protective effects of EntV in the OPC model are due to its activity against other bacterial species in the mouth, although we would expect this to enhance fungal colonization rather than suppress it. We are thus only beginning to understand the complex interactions among the microbiota and their varied effects on the human host, but the knowledge is likely to have important impacts on the development of novel antimicrobials.

Materials and Methods

Microbiological and Molecular Biological Methods.

Candida and Enterococcus strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. Standard culture media were used for routine propagation, as described in SI Materials and Methods. The entV mutant strain was constructed as described to create an in-frame markerless deletion by using a P-pheS* counterselection system (46) and complemented by using a reported strategy to regenerate the wild-type locus (47). The recombinant hexahistidine-tagged 136-aa EntV propeptide was expressed from pET28a in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified on TALON resin, as described (48). Attempts to purify the fully active 68-aa peptide from E.coli were unsuccessful; the peptide was synthesized with the disulfide bond (Lifetein). The hyphal-specific HWP1p-GFP reporter strain DHC271 (21) expressing a constitutive mCherry was generated via transformation with plasmid pADH1-mCherry (49).

Table S1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain | Designation/species | Relevant genotype/characteristic | Parent | Source |

| Candida albicans strains | ||||

| SC5314 | Wild-type | Prototroph | — | (59) |

| DHC271 | HWP1-GFP | ura3/ura3ENO1/eno1::HWP1p-GFP-URA3 | SC5314 | (21) |

| CEGC1 | HWP1-GFP ADH1-mCherry | ura3/ura3ENO1/eno1::HWP1p-GFP-URA3 RPS10/rps10::ADH1p-mCherry-SAT1 | DHC271 | This study |

| Other fungal strains | ||||

| MYA3404 | Candida tropicalis | Prototroph | — | (60) |

| CLIB298 | Candida glabrata | Prototroph | — | (60) |

| J941367 | Candida parapsilosis | Prototroph | — | (60) |

| Enterococcus faecalis strains | ||||

| OG1RF | Wild-type | Gel+ Spr+ RfR FaR | OG1 | (61) |

| TX5266 | ΔfsrB | fsrB in-frame deletion mutant (bp 79–684); | OG1RF | (62) |

| Gel− Spr− RifR FaR KanR | ||||

| CK111 | Conjugative donor | upp4::P23repA4, SpR | OG1Sp | (46) |

| CEGF1 | ΔentV | Markerless deletion of entV; RfR FaR | OG1RF | This study |

| CEGF2 | ΔentV/ entV | Reconstituted entV with a silent nucleotide change, Δef1097 [entV*], RfR FaR | CEGF1 | This study |

| Escherichia coli strains and plasmids | ||||

| EC1000 | — | E. coli cloning host for pCJK47-based plasmids; provides RepA in trans | — | (63) |

| DH5α | — | E. coli cloning host for routine cloning | — | Invitrogen |

| BL21 (DE3) | — | E. coli cloning host for routine cloning, suitable for protein expression | — | Invitrogen |

| CEGE1 | — | BL21 (DE3) with pET28a containing entV136 | — | This study |

| pCJK47 | — | Plasmid for markerless exchange, oriTpCF10 and P-pheS*; EmR | — | (46) |

| pET28a | — | Recombinant expression vector, N-terminal His•Tag/thrombin/T7•Tag configuration plus an optional C-terminal His•Tag sequence, IPTG or lactose inducible | — | Novagen |

In Vitro Biofilm Assays.

Biofilm assays in conditions mimicking the oral cavity were modified from published reports (15, 50, 51) by using an artificial saliva media [0.17% Yeast Nitrogen Base (vol/vol), 0.5% casamino acids (vol/vol), 0.25% mucin (vol/vol), 14 mM potassium chloride, 8 mM sodium chloride, 100 μM choline chloride, 50 μM sodium citrate, 5 μM ascorbate] adapted from ref. 19. This media was supplemented with conditioned bacterial supernatant or recombinant or synthetic peptide, as indicated. Biofilm development was allowed to proceed for 24–48 h and then assessed in three ways: by estimating biomass using the redox dye resazurin, as described (20), by measuring fluorescence from the HWP1p-GFP hyphal-specific reporter strain (21), or through confocal microscopy.

Nematode Infection Model.

C. elegans glp-4(bn2);sek-1(km4) nematodes were propagated by using standard techniques on E. coli strain OP50 on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar (52). The liquid infection assay was performed as described (17, 28); briefly, young adults were incubated for 4 h on solid medium with the wild-type C. albicans SC5314 strain, then the worms were collected, washed, and transferred to six-well plates containing 20% Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) and 80% M9W, after which viability was assayed daily. Filamentation of C. albicans within the worms was scored via microscopic analysis.

Murine Macrophage Infection.

To assess whether EntV68 protects phagocytes from fungal-induced damage, we used a coculture assay in which C. albicans cells were incubated with RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells as described (32). Fungal viability was assessed by using a modified end-point dilution assay in which respiratory activity is measured using a tetrazolium dye, XTT (53, 54). Lactate dehydrogenase was assayed by using the Cytotox96 kit (Promega). C. albicans morphology was assayed microscopically.

Murine Oropharyngeal Candidiasis Model.

Adult BALB/c mice were immunosuppressed with subcutaneous injections of cortisone acetate before sublingual inoculation with C. albicans according to Solis and Filler (36). Mice were given EntV or vehicle in drinking water ad libitum. Three and five days after inoculation, mice were euthanized and the tongues excised and halved longitudinally. Part of the tongue was processed for histopathological analysis, whereas the rest was homogenized for assessment of fungal burden via qPCR. DNA was extracted by using the Yeast DNA Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific), and the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS1) of the rDNA genes was amplified as described (38, 39). Experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

SI Materials and Methods

Strains and Culture Conditions.

Bacterial and fungal strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. Media was purchased from DIFCO and chemicals from Sigma, unless otherwise stated. Escherichia coli strains were cultured in Luria Bertani broth overnight at 37 °C with antibiotics where appropriate by using the following concentrations (µg/mL): kanamycin, 50; spectinomycin, 100; erythromycin 300. E. faecalis strains were cultured overnight at 37 °C in BHI medium or M9HY (55) with 100 μM glucose. Addition of antibiotics where applicable were at the following concentrations (µg/mL): erythromycin, 50; and rifampicin, 100. Fungal strains were propagated in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) (56). All C. albicans biofilms were grown in artificial saliva (YNB-AS) modified from Wong et al. (19) [0.17% YNB (vol/vol), 0.5% casamino acids (vol/vol), 0.25% mucin (vol/vol), 14 mM potassium chloride, 8 mM sodium chloride, 100 μM choline chloride, 50 μM sodium citrate, 5 μM ascorbate]. For all nematode liquid killing assays, C. elegans glp-4(bn2);sek-1(km4) nematodes were used and propagated by using standard techniques on E. coli strain OP50 on NGM agar (28, 52, 57).

Strain Construction.

The entV mutant strain was constructed as described to create an in-frame markerless deletion by using a P-pheS* counterselection system (46). Briefly, sequences flanking the 5′ and 3′ ends of entV were amplified by PCR. The two products were fused together by PCR with primer-introduced NotI and Pst1 sites. The resulting fragment was ligated into NotI/PstI-digested pCJK47 vector, resulting in pCEG1. pCEG1 was electroporated into CK111 cells, and counterselection was completed to create strain CEG1F. Deletion of entV was confirmed by PCR and sequencing. The entV complement strain was constructed by using a previously described strategy in which the wild-type locus is regenerated with a silent mutation in the gene to distinguish it from the original wild-type strain (47). To generate entV*, a mutation (CTT) was introduced into the leucine codon TTA corresponding to amino acid position 50 by using the primers pmF and pmR. The hyphal specific reporter strain (HWP1p::GFP) was transformed with plasmid pADH1-mCherry (ADH1p::mCherry) to construct a C. albicans strain expressing both hyphal-specific GFP and constitutive mCherry (49).

C. albicans Biofilm Assay.

The C. albicans biofilm assay was developed by using a similar technique as described with the following modifications (15, 50, 51). C. albicans strains were grown overnight at 30 °C in YPD and washed three times with PBS, and the final OD600 was adjusted to 0.2 (∼1 × 107 cell/mL) in PBS. Tissue culture-treated 96-well polystyrene plates (Corning) or chambered polystyrene slides (Ibidi) were inoculated with C. albicans in PBS and incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. Inoculated plates and slides were then gently washed with PBS. After removal of PBS, YNB-AS was added with 50% bacterial supernatant or sterile M9HY and incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h. The supernatant of E. faecalis (OG1RF, ΔfsrB, ΔentV, ΔentV/entV) was collected as described (17). Biofilms grown with rEntV136 or sEntV68 were grown similarly with the peptide added to the YNB-AS medium at the appropriate concentrations and compared with Hepes or DMSO vehicle controls, respectively. After 24–48 h of growth, biofilms were washed three times with PBS and hyphal morphogenesis and biofilm biomass were assessed.

Hyphal morphogenesis was quantified in C. albicans (HWP1::pGFP) biofilms grown in 96-well microplates by measuring GFP fluorescence; fluorescence intensity (excitation 488 nm, emission 520 nm) was determined by using a fluorescence microplate reader (SynergyMX, Biotek). The relative fluorescence was calculated per well as a ration of GFP fluorescence to cell density (OD600) and normalized to control treated biofilms (sterile medium, Hepes, or DMSO). Biofilm biomass was determined by resazurin staining of C. albicans biofilms as described (20), using 0.015 mg/mL resazurin for up to 1 h in the dark.

For microscopic imaging, C. albicans biofilms were gently washed in PBS, as stated above. Wild-type C. albicans (SC5341) were stained by using 35 mg/mL calcofluor white for 5 min in the dark and imaged using 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and differential interference contrast (DIC) filters on an Olympus IX81 automated inverted microscope with Slidebook software (version 6.0) or Nikon A1R Confocal Laser automated inverted microscope system with NIS Elements (version 4.5).

All biofilm assays were done in triplicate for three independent experiments. The different treatment types per experiment were compared by pairwise by Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA with a P value of <0.05 considered statistically significant using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0).

Expression and Purification of Recombinant EntV.

Hexahistidine-tagged EntV136 was expressed as described (48) with the following modifications. The coding regions of EntV (residues 35–171) were cloned in the pET28a vector and transformed in to E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer [25 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0, 0.1 M sodium chloride, 1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol and 1 mM PMSF] by sonication for 10 min on an ice water bath followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min.

The clarified lysate was then loaded on to a preequilibrated TALON affinity resin (Clontech) and washed three times with 10 column volumes each of wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM imidazole). The hexahistidine-tagged protein was eluted in elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM sodium chloride, 150 mM imidazole) and elution fractions were collected. Samples with purified protein were combined and dialyzed against buffer containing 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.0. The collected fractions were then subjected to Tricine-SDS/PAGE and analyzed by Western blot using anti-His antibodies (THE, GenScript).

C. elegans Infection Model.

The methodology used for the C. elegans infection liquid assay, with a few minor modifications, was described (17, 28). Briefly, synchronized, young adult nematodes were sequentially preinfected with C. albicans for 4 h on BHI agar medium containing gentamicin (10 μg/mL). The nematodes were then washed four times with 2 mL of sterile M9W. They were collected by centrifugation at 750 × g between each wash and before being pipetted (∼30 worms per well with 2 wells per condition for a total of approximately 60 worms assayed) into wells of a six-well microtiter dish (BD Falcon) containing 2 mL of liquid medium (20% BHI and 80% M9W) and various concentrations of sEntV68. Plates were incubated at 25 °C, and worm death was scored daily. Kaplan–Meier log rank analysis was used to compare survival curves pairwise. P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The software GraphPad Prism (version 6.0) was used for the analyses.

Assays for filamentation were set up as described above for the survival assays. Plates were incubated at 25 °C and examined on days 4 and 7 for penetrative filamentation of nematodes by using a Zeiss Stemi 2000 microscope. Penetrative filamentation was defined as any breach in the worm cuticle by filamentous cells as seen at 5× magnification. All experiments were performed at least three times and compared pairwise by the Student’s t test using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0), with P values of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Murine Macrophage Infection.

The activity of sEntV68 against C. albicans was evaluated in the murine macrophage infection model by using the end point dilution assay (53, 54). Briefly, RAW264.7 murine macrophages were seeded in a 96-well plate with RPMI medium 1640 with phenol red supplemented with 10% FBS (RPMI-10) at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells/mL per well and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After overnight growth at 30 °C in YPD, C. albicans cultures were washed twice with PBS and resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/mL in RPMI minus phenol with 100 nM sEntV68 or DMSO and incubated at room temperature (RT) with shaking for 1.5 h. The macrophage seeded 96-well plate was inoculated with serial dilutions of the pretreated C. albicans cell suspension. Media-only controls were prepared in the same manner. The plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 15 h. Fungal biomass was determined by quantification of C. albicans microcolonies using the XTT assay as described (58). Absorbance was read at 451 nm in a microplate reader (SynergyMX, Biotek). Assays were performed with replicates in three independent experiments.

Protection of macrophages by sEntV68 was examined by monitoring cytotoxicity of C. albicans on macrophages using the CytoTox96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity assay (Promega) that measures release of LDH (32). RAW264.7 murine macrophages in RPMI-10 were seeded in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells per mL and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. C. albicans cell suspensions were prepared at 1.5 × 106 cells per mL in RPMI minus phenol with 100 nM sEntV68 or DMSO and incubated at RT with shaking for 1.5 h. Media-only controls were also prepared in the same manner. The macrophage seeded plates were inoculated with the pretreated C. albicans cell suspension and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 5 h. LDH release was normalized to chemically lysed macrophages, and assays were performed with replicates in three independent experiments.

Hyphal morphogenesis of C. albicans in phagocytes was quantified after infection of RAW264.7 murine macrophages as described above with the following modifications. Macrophages were seeded on glass coverslips in 12-well plates at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells per mL and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Overnight cultures of CEG1C (HWP1p::GFP; ADH1p::mCherry) were subcultured in YPD for 5 h at 30 °C. Cells were collected and washed with PBS, and diluted in RPMI minus phenol with 100 nM sEntV68 or DMSO to a concentration of 1.5 × 106 cells per mL and incubated at RT with shaking for 1.5 h. Media-only controls were also prepared in the same manner. The macrophage-seeded glass coverslips were inoculated with the pretreated C. albicans cell suspension and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 2 h. The media was aspirated and cells were fixed in 2.7% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.5) for 15 min at 37 °C followed by washing twice with PBS. Images were captured by using Tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC), FITC, and DIC filters on an Olympus IX81 automated inverted microscope with Slidebook software (version 6.0). Cell enumeration was performed by using at least 10 different fields of view and at least 200 cells per treatment from replicates in three independent experiments.

sEntV Toxicity Assay.

Toxicity of sEntV68 on murine macrophages (RAW264.7) and human cervical epithelial cells (HeLa) was examined by monitoring LDH release, as above. RAW264.7 murine macrophages in RPMI-10 and HeLa cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with high glucose and 10% FBS (DMEM-HG-10) were seeded in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells per mL and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Media from the seeded plates was replaced with media containing 10 μM sEntV68 and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for up to 72 h. LDH release was measured every 24 h, and the percentage of maximum LDH was calculated as a ratio of LDH from treated cells to LDH from chemically lysed cells.

Oropharyngeal Candidiasis Model.

The efficacy of sEntV68 was tested in the OPC model as described (36). Mice were immunosuppressed by injecting cortisone acetate s.c. in the dorsum of the neck at a concentration of 225 mg/kg of body weight 1 d before inoculation, and subsequently on days 1 and 3 of the infection. Before inoculation with C. albicans mice were anesthetized with an i.p. injection of 0.1 mL/10 g of body weight with 10 mg/mL ketamine and 1 mg/mL xylazine and placed on prewarmed hot water blankets. C. albicans was grown at 30 °C in YPD broth overnight and subcultured twice before washing with PBS twice and preparing cell suspensions in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) at 1 × 106 cells/mL. Calcium alginate swabs were immersed in the C. albicans suspension with 100 nM sEntV68 or DMSO for 5 min and then used to inoculate the mice sublingually for 75 min.

The mice were monitored continuously for signs of waking up (movement of extremities and/or blinking of the eyes) and were given additional doses of ketamine, as necessary (without xylazine, 50 mg ketamine/kg of body weight). After inoculation mice were treated with 100 nM sEntV68 or DMSO in the drinking water for the remainder of the experiment. Mice were euthanized at 3 and 5 d after inoculation. The tongues were excised for tissue histology and assessment of the fungal burden.

Tongues were fixed in zinc-buffered formalin followed by paraffin embedding. Thin sections of the tongues were stained with periodic acid–Schiff (36). Tissue histology was observed by using a light microscope. Images were captured at 40×, and histology was quantified by measuring the percentage of infected epithelium relative to the entire epithelial area (37). The complete epithelial area and infected epithelium were measured from 40× images taken of the entire tissue section of each sample. For each image, the total area of epithelium and infected epithelium were measured by using ImageJ (version 1.5). Measurements were totaled and expressed as a percentage of total infected epithelium relative to the entire totaled epithelial area.

For examination of fungal burden, qPCR was used by amplifying a 269-bp fragment of internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) between the 5.8S and 28S ribosomal RNA genes of C. albicans (38, 39). DNA was extracted by using the Yeast DNA Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the protocol with the following modifications. A portion of tongue from each mouse was homogenized in 300 μL of Y-PER reagent for 8- to 10-sec increments with incubation on ice until samples were completely homogenized followed by incubation at 65 °C for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min, supernatant discarded, 400 μL of Reagent A and 400 μL of Reagent B was added, vortexed, and incubated at 90 °C for 3 h. After treatment protein removal agent DNA was precipitated with isopropyl alcohol and washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in sterile ultrapure water.

The ITS2 fragment was amplified from the DNA extractions and qPCR was performed with a CFX96 Real-Time System with a C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). A standard curve was generated by using C. albicans genomic DNA ranging from 0.5 to 5,000 pg. C. albicans DNA was quantified by using FastStart Universal SYBR Green master mix with ROX (Roche). Reactions were setup according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. To screen for contamination and background fluorescence during qPCR amplification, no template controls were used. Noninfected mouse tongues and extraction-negative controls were processed in parallel with tissue samples to test for possible contamination during homogenization and extraction.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Wheeler, D. Hogan, and P. Sundstrom for reagents; other members of the M.C.L. and D.A.G. laboratories for helpful conversations and advice; and Drs. Barrett Harvey, Ambro van Hoof, and Michael Gustin for their input. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Awards R01AI075091 (to M.C.L.), R01AI076406 and R01AI110432 (to D.A.G.), and F31AI122725 (to C.E.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1620432114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Agudelo Higuita NI, Huycke MM. Enterococcal disease, epidemiology, and implications for treatment. In: Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N, editors. Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection. Mass Eye Ear Infirmary; Boston: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lebreton F, Willems RJL, Gilmore MS. Enterococcus diversity, origins in nature, and gut colonization. In: Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N, editors. Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection. Mass Eye Ear Infirmary; Boston: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran G, Coleman D, Sullivan D. 2012. An introduction to the medically relevant Candida species. Candida and Candidiasis, eds Calderone RA, Clancy CJ (Am Soc Microbiol, Washington), pp 11–26.

- 4.Oever JT, Netea MG. The bacteriome-mycobiome interaction and antifungal host defense. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:3182–3191. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayr FB, Yende S, Angus DC. Epidemiology of severe sepsis. Virulence. 2014;5:4–11. doi: 10.4161/viru.27372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermann C, Hermann J, Munzel U, Rüchel R. Bacterial flora accompanying Candida yeasts in clinical specimens. Mycoses. 1999;42:619–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.1999.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunny GM, Hancock LE, Shankar N. Enterococcal biofilm structure and role in colonization and disease. In: Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N, editors. Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection. Mass Eye Ear Infirmary; Boston: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nobile CJ, Johnson AD. Candida albicans biofilms and human disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai JV, Mitchell AP, Andes DR. Fungal biofilms, drug resistance, and recurrent infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a019729. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garsin DA, Lorenz MC. Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis in the gut: Synergy in commensalism? Gut Microbes. 2013;4:409–415. doi: 10.4161/gmic.26040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peleg AY, Hogan DA, Mylonakis E. Medically important bacterial-fungal interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:340–349. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA, O’May GA, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. Polymicrobial interactions: Impact on pathogenesis and human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:193–213. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogan DA, Kolter R. Pseudomonas-Candida interactions: An ecological role for virulence factors. Science. 2002;296:2229–2232. doi: 10.1126/science.1070784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morales DK, et al. Control of Candida albicans metabolism and biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazines. MBio. 2013;4:e00526-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00526-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters BM, et al. Microbial interactions and differential protein expression in Staphylococcus aureus -Candida albicans dual-species biofilms. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;59:493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bamford CV, et al. Streptococcus gordonii modulates Candida albicans biofilm formation through intergeneric communication. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3696–3704. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00438-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruz MR, Graham CE, Gagliano BC, Lorenz MC, Garsin DA. Enterococcus faecalis inhibits hyphal morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 2013;81:189–200. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00914-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rautemaa R, Ramage G. Oral candidosis--clinical challenges of a biofilm disease. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2011;37:328–336. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2011.585606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong L, Sissons C. A comparison of human dental plaque microcosm biofilms grown in an undefined medium and a chemically defined artificial saliva. Arch Oral Biol. 2001;46:477–486. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(01)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van den Driessche F, Rigole P, Brackman G, Coenye T. Optimization of resazurin-based viability staining for quantification of microbial biofilms. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;98:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staab JF, Bahn YS, Sundstrom P. Integrative, multifunctional plasmids for hypha-specific or constitutive expression of green fluorescent protein in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 2003;149:2977–2986. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baillie GS, Douglas LJ. Role of dimorphism in the development of Candida albicans biofilms. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:671–679. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-7-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramage G, VandeWalle K, López-Ribot JL, Wickes BL. The filamentation pathway controlled by the Efg1 regulator protein is required for normal biofilm formation and development in Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;214:95–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourgogne A, Hilsenbeck SG, Dunny GM, Murray BE. Comparison of OG1RF and an isogenic fsrB deletion mutant by transcriptional analysis: The Fsr system of Enterococcus faecalis is more than the activator of gelatinase and serine protease. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2875–2884. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.2875-2884.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dundar H, et al. The fsr quorum-sensing system and cognate gelatinase orchestrate the expression and processing of Proprotein EF_1097 into the mature antimicrobial peptide enterocin O16. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:2112–2121. doi: 10.1128/JB.02513-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teixeira N, et al. Drosophila host model reveals new enterococcus faecalis quorum-sensing associated virulence factors. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swe PM, et al. ef1097 and ypkK encode enterococcin V583 and corynicin JK, members of a new family of antimicrobial proteins (bacteriocins) with modular structure from Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology. 2007;153:3218–3227. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/010777-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breger J, et al. Antifungal chemical compounds identified using a C. elegans pathogenicity assay. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo HJ, et al. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell. 1997;90:939–949. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saville SP, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL. Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:1053–1060. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.5.1053-1060.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorenz MC, Bender JA, Fink GR. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:1076–1087. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.5.1076-1087.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vylkova S, Lorenz MC. Modulation of phagosomal pH by Candida albicans promotes hyphal morphogenesis and requires Stp2p, a regulator of amino acid transport. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003995. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sangeorzan JA, et al. Epidemiology of oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: Colonization, infection, treatment, and emergence of fluconazole resistance. Am J Med. 1994;97:339–346. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhodus NL, Bloomquist C, Liljemark W, Bereuter J. Prevalence, density, and manifestations of oral Candida albicans in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Otolaryngol. 1997;26:300–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willis AM, et al. Oral candidal carriage and infection in insulin-treated diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 1999;16:675–679. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solis NV, Filler SG. Mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:637–642. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moyes DL, et al. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature. 2016;532:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nature17625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khot PD, Ko DL, Fredricks DN. Sequencing and analysis of fungal rRNA operons for development of broad-range fungal PCR assays. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1559–1565. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02383-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rickerts V, Khot PD, Ko DL, Fredricks DN. Enhanced fungal DNA-extraction from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens by application of thermal energy. Med Mycol. 2012;50:667–672. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.665613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierce CG, et al. A novel small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicans biofilm formation, filamentation and virulence with low potential for the development of resistance. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2015;1:15012. doi: 10.1038/npjbiofilms.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mason KL, et al. Interplay between the gastric bacterial microbiota and Candida albicans during postantibiotic recolonization and gastritis. Infect Immun. 2012;80:150–158. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05162-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mason KL, et al. Candida albicans and bacterial microbiota interactions in the cecum during recolonization following broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Infect Immun. 2012;80:3371–3380. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00449-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hogan DA, Vik A, Kolter R. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule influences Candida albicans morphology. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:1212–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azoulay E, et al. Outcomerea Study Group Candida colonization of the respiratory tract and subsequent pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2006;129:110–117. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neely AN, Law EJ, Holder IA. Increased susceptibility to lethal Candida infections in burned mice preinfected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa or pretreated with proteolytic enzymes. Infect Immun. 1986;52:200–204. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.200-204.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kristich CJ, Chandler JR, Dunny GM. Development of a host-genotype-independent counterselectable marker and a high-frequency conjugative delivery system and their use in genetic analysis of Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid. 2007;57:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montealegre MC, La Rosa SL, Roh JH, Harvey BR, Murray BE. The Enterococcus faecalis EbpA pilus protein: Attenuation of expression, biofilm formation, and adherence to fibrinogen start with the rare initiation codon ATT. MBio. 2015;6:e00467-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00467-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fox KA, et al. Multiple posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms partner to control ethanolamine utilization in Enterococcus faecalis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4435–4440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812194106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brothers KM, Newman ZR, Wheeler RT. Live imaging of disseminated candidiasis in zebrafish reveals role of phagocyte oxidase in limiting filamentous growth. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:932–944. doi: 10.1128/EC.05005-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nobile CJ, et al. A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell. 2012;148:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nobile CJ, Mitchell AP. Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1150–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hope IA. C. elegans A Practical Approach. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miramón P, Lorenz MC. The SPS amino acid sensor mediates nutrient acquisition and immune evasion in Candida albicans. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:1611–1624. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rocha CR, et al. Signaling through adenylyl cyclase is essential for hyphal growth and virulence in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3631–3643. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Del Papa MF, Perego M. Ethanolamine activates a sensor histidine kinase regulating its utilization in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7147–7156. doi: 10.1128/JB.00952-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moy TI, et al. Identification of novel antimicrobials using a live-animal infection model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10414–10419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604055103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miramón P, et al. A family of glutathione peroxidases contributes to oxidative stress resistance in Candida albicans. Med Mycol. 2014;52:223–239. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myt021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fonzi WA, Irwin MY. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Butler G, et al. Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature. 2009;459:657–662. doi: 10.1038/nature08064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murray BE, et al. Generation of restriction map of Enterococcus faecalis OG1 and investigation of growth requirements and regions encoding biosynthetic function. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5216–5223. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5216-5223.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qin X, Singh KV, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. Characterization of fsr, a regulator controlling expression of gelatinase and serine protease in Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3372–3382. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.11.3372-3382.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leenhouts K, et al. A general system for generating unlabelled gene replacements in bacterial chromosomes. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;253:217–224. doi: 10.1007/s004380050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]