Significance

We show that emissions from riverine systems depend on river and stream size and that the primary source of production shifts from the hyporheic and benthic zones in streams to the benthic and water column in rivers. This analysis also reveals the primary scaling factors governing riverine emissions. Finally, it provides a predictive tool to quantify emissions from any riverine environment worldwide, among biomes, land-use types, and climatic conditions, using readily available reach-scale biogeochemical measurements and hydromorphological data.

Keywords: riverine networks, greenhouse gas, N2O, emission scaling law, N2O emission potentials

Abstract

Riverine environments, such as streams and rivers, have been reported as sources of the potent greenhouse gas nitrous oxide () to the atmosphere mainly via microbially mediated denitrification. Our limited understanding of the relative roles of the near-surface streambed sediment (hyporheic zone), benthic, and water column zones in controlling production precludes predictions of emissions along riverine networks. Here, we analyze emissions from streams and rivers worldwide of different sizes, morphology, land cover, biomes, and climatic conditions. We show that the primary source of emissions varies with stream and river size and shifts from the hyporheic–benthic zone in headwater streams to the benthic–water column zone in rivers. This analysis reveals that production is bounded between two emission potentials: the upper emission potential results from production within the benthic–hyporheic zone, and the lower emission potential reflects the production within the benthic–water column zone. By understanding the scaling nature of production along riverine networks, our framework facilitates predictions of riverine emissions globally using widely accessible chemical and hydromorphological datasets and thus, quantifies the effect of human activity and natural processes on production.

Riverine environments, such as streams and rivers, have been identified as hotspots of microbially mediated denitrification, where nitrate () is converted to both nitrogen gas (), which constitutes the majority of Earth’s atmosphere, and nitrous oxide (), the potent greenhouse gas responsible for stratospheric ozone destruction (1). Denitrification has been observed to occur within both bulk-oxic (2) and anoxic environments (3–5) of both benthic (i.e., sediment–water interface) and hyporheic (i.e., near-subsurface) zones of streams and rivers. Whereas the benthic zone is the ecological region of the streambed, where both aquatic fauna and flora can be found (4, 6), the latter is the band of streambed material mainly saturated of stream water (7). The benthic zone is at the interface between water and sediment and the upper boundary of the fluvial hyporheic zone. Current understanding suggests that riverine production occurs predominantly in these two environments, reflecting two distinct biogeochemical transformation zones (6), irrespective of system size from headwater streams to rivers. The produced is then exchanged with the atmosphere through diffusive evasion, with dynamics that depend on concentrations of the water in relation to atmospheric equilibrium (6, 8), stream hydrodynamics, temperature, and the air–water gas exchange rate (9). Although it is understood that microbially mediated denitrification is responsible for a large proportion of production in riverine networks (6, 10, 11), quantifying these emissions is challenging because of a lack of high-resolution field data and inadequate parameterization of the dominant biogeochemical processes responsible for production at scales ranging from the individual reach to the river network. In addition to the uncertainty associated with predictions of emissions from streams and rivers, recent studies suggest that global emissions from riverine networks presented in the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report are likely underestimated (6, 12–14). This uncertainty results in part from the dependence of biogeochemical reactions on complex interactions occurring at the reach scale among the water column, benthic, and hyporheic zones. A key factor, which has been elusive in previous works, is the identification of a scaling relationship that allows us to upscale processes occurring within a single reach to best quantify emissions at the riverine network scale. This scaling relationship is needed to improve climate change models that account for anthropogenic activities and natural processes on streams and rivers and the consequent emission from these systems.

Here, we identify and define this scaling law by linking, through a model, emissions with geomorphic, hydrodynamic, and biogeochemical characteristics of streams and rivers and their hyporheic zones, thereby proposing a methodology to upscale reach-scale processes to riverine networks globally. Our model identifies the primary hydrodynamics and biogeochemical processes responsible for emissions from streams and rivers. Hydrodynamics controls the delivery of reactants to microbial assemblages and determines residence times for reactions to occur (5, 15–17), whereas solute availability and biogeochemical activity drive the conversion of solutes to gasses. This analysis shows that production per unit of stream/river surface area from the river network worldwide is bounded between two emission potentials: the upper emission potential is caused by production within the benthic–hyporheic interface, and the lower emission potential is caused by production within the benthic–water column zone. These two limits emerge, because emissions per unit area reduce moving downstream from streams to rivers because of the systematic reduction of the hyporheic contribution, which is only partially compensated by the increase of the contribution from the water column (4, 12, 18). We assumed that ammonium entering via groundwater, or other routes, is quickly nitrified, such that in-stream processes (i.e., hyporheic zone, benthic, and water column) are the primary source of emissions, whereas direct contribution, which may enter the streams from groundwater or terrestrial origin, is negligible (6).

We unveiled this scaling and developed our model by analyzing available emission data and hydromorphological parameters of 12 headwater streams in the Kalamazoo River (Michigan) watershed (19, 20) and 16 headwater streams associated with the second Lotic Intersite Nitrogen eXperiment (LINXII) Study (6, 10, 11). These data allow us to parse the relative roles of the benthic and hyporheic zones in emissions and constrain them between two limits: upper- and lower-bound models. We then validated the scaling law and the identified upper- and lower-bound models with data that we collected during synoptic sampling campaigns along the Tippecanoe River (Indiana) and Manistee River (Michigan) watersheds and data available in the literature collected in a midsized United Kingdom river (21, 22) (Swale-Ouse River), six large river networks in Africa (23) (Athi–Galana–Sabaki, Betsiboka, Congo, Rianila, Tana, and Zambezi), and a large tidal river (24, 25) (Hudson River in New York) (6, 10, 19–25) (descriptions of these streams are in Tables S1, S2, and S3). These streams are more than 400 testing reaches with contrasting land use land cover (LULC), biomes, climatic conditions, morphology, and size (Table S4).

Table S1.

Hydraulics parameters used to compute the timescale of vertical mixing, , and the median hyporheic residence time, ( is the number of analyzed stream reaches)

| River name | Location | Parameters | Source | |

| AGS | Africa | 26 | a | Supplemental information in Borges et al. (23) |

| Betsiboka | Africa | 26 | a | Supplemental information in Borges et al. (23) |

| Congo | Africa | 52 | a | Supplemental information in Borges et al. (23) |

| Hudson | United States | 53 | Figure 1 in Caraco et al. (25) | |

| Kalamazoo | United States | 12 | Table 1 in Beaulieu et al. (19) | |

| LINXII Study | United States | 16 | Table S1 in Mulholland et al. (10) | |

| Manistee | United States | 50 | This research | |

| Rianila | Africa | 21 | a | Supplemental information in Borges et al. (23) |

| Swale-Ouse | Europe (United Kingdom) | 19 | Figure 3 in Pattinson et al. (21) | |

| Tana | Africa | 20 | a | Supplemental information in Borges et al. (23) |

| Tippecanoe | United States | 76 | This research | |

| Zambezi | Africa | 61 | a | Supplemental information in Borges et al. (23) |

The values of the stream width are obtained from Google Earth at the sampling site location.

Table S2.

Range of variation (minimum–maximum) of the hydromorphological parameters used in the characterization of the median hyporheic residence time and the characteristic time of mixing

| Stream or river | (m) | (m) | (m/s) | (m3/s) | (m/s) | |

| AGS | 0.314–3.260 | 5.110–128.630 | 0.143–0.306 | 0.230–128.483 | 0.0024–0.012 | 0.004 |

| Betsiboka | 0.496–9.481 | 5.190–642.640 | 0.184–1.451 | 0.474–8,839.145 | 0.0106–0.013 | 0.004 |

| Congo | 0.394–120.189 | 10.470–3,197.470 | 0.127–0.344 | 0.524–132,264.069 | 0.0000–0.007 | 0.004 |

| Hudson | 2.786–16.523 | 344.595–4,335.220 | 1.771–3.087 | 1,836.428–39,105.813 | 0.0173–0.104 | 0.0005 |

| Kalamazoo | 0.055–0.159 | 1.108–4.009 | 0.020–0.162 | 0.003–0.063 | 0.0009–0.064 | 0.00044 |

| LINXII Study | 0.020–1.120 | 0.800–5.700 | 0.015–0.492 | 0.0002–0.189 | 0.4000–3.171 | 0.00032–0.00412 |

| Manistee | 0.120–0.982 | 0.122–57.460 | 0.030–1.500 | 0.023–20.513 | 0.0050–1.444 | 0.0035–0.0065 |

| Rianila | 0.183–3.203 | 4.080–250.870 | 0.089–1.430 | 0.067–1,149.309 | 0.0094–0.053 | 0.004 |

| Swale-Ouse | 0.195–0.940 | 4.454–42.843 | 0.095–0.435 | 0.080–16.963 | 0.0097–0.025 | 0.0005–0.005 |

| Tana | 0.386–9.537 | 10.280-253.770 | 0.127–0.222 | 0.504–535.943 | 0.0003–0.007 | 0.004 |

| Tippecanoe | 0.060–1.155 | 0.914–68.380 | 0.010–0.716 | 0.001–8.886 | 0.0010–0.549 | 0.0035 |

| Zambezi | 0.494–20.946 | 13.130–1,077.000 | 0.132–0.285 | 0.858–6,135.192 | 0.0001–0.006 | 0.004 |

In particular, Y0(m) is the mean flow depth, W(m) is the channel width, V(m/s) is the mean stream velocity, Q(m3/s) is the water discharge, s0(%) is the stream slope, and Kh(m/s) is the alluvium hydraulic conductivity. Hydraulic conductivity is evaluated by using the following relationship: Kh = 16:88+10:6d50, where Kh is in meters per day and d50 is in millimeters (49) if the median sediment size d50 was available (otherwise by using texture information). When resorting to texture, the same value of Kh was used for all of the reaches of stream/river, and this assumption is evidenced by the fact that minimum and maximum values are coincident.

Table S3.

Range of variation (minimum–maximum) of the parameters used to characterize the time of denitrification and the Damköhler numbers of the benthic–hyporheic zone and the benthic–water column for all of the analyzed streams and rivers

| Stream or river | (cm/s) | gN/L) | ||||

| AGSa | 1.300–13.173 | 68.600–7526.400 | 6.947–255.374 | 0.004–0.144 | 0.188–1.506 | 0.718–8.094 |

| Betsibokaa | 8.335–89.734 | 1.400–173.600 | 3.761–105.421 | 0.009–0.266 | 0.205–2.403 | 1.421–18.478 |

| Rianilaa | 8.963–89.734 | 1.400–149.800 | 0.583–38.397 | 0.026–1.716 | 0.066–3.861 | 1.116–49.974 |

| Tanaa | 2.600–5.598 | 389.200–1,843.800 | 17.200–210.351 | 0.005–0.058 | 0.273–4.455 | 2.382–5.016 |

| Zambezia | 4.405–89.734 | 1.400–632.800 | 3.673–446.058 | 0.002–0.272 | 0.612–171.579 | 4.023–80.013 |

| Congoa | 3.782–52.208 | 4.200–862.400 | 1.580–1,424.129 | 0.001–0.633 | 0.844–87.305 | 3.436–46.648 |

| Hudsona | 4.756–6.447 | 292.308–541.807 | 55.349–375.428 | 0.003–0.018 | 0.134–0.517 | 0.340–0.579 |

| Manisteeb | 0.906–592.386 | 4.809–2,803.800 | 0.100–36.287 | 0.028–10.021 | 0.008–142.145 | 0.088–61.567 |

| Tippecanoeb | 0.558–214.516 | 13.043–4,515.875 | 0.221–87.169 | 0.011–4.521 | 0.010–209.290 | 0.082–225.774 |

| Swale-Ousec | 0.629–20.026 | 9.358–13,126.358 | 1.221–173.078 | 0.006–0.819 | 0.109–14.140 | 3.750–651.357 |

| LINXIId | 0.143–95.667 | 35.000–4,158.000 | 0.126–16.150 | 0.062–7.930 | 0.026–835.392 | 0.076–4.676 |

| Kalamazooe | 0.664–64.815 | 30.000–21,760.000 | 0.098–15.518 | 0.064–10.182 | 0.324–140.362 | 0.710–68.662 |

Note that Uden (micrograms N per square meter per hour) is the areal uptake rate of denitrification, [NO3] (micrograms N per liter) is the nitrate concentration in the water, kD (d−1) is the reaction rate of denitrification, and Y0 (cm) is the mean flow depth. Equations used to obtain the uptake rate of denitrification vfden are also reported.

| [S19] |

| [20] |

| [S21] |

| [S22] |

Table S4.

Timing of sample collection, LULC, and range of variation (minimum–maximum) in stream temperature (degrees Celsius), stream ammonium concentration (micrograms N per liter), stream nitrate concentration (micrograms N per liter), and stream nitrous oxide concentration (micrograms N per liter) along the analyzed streams and rivers

| River name | Year | LULC | () | (gN/L) | (gN/L) | (gN/L) |

| AGS | 2010–2012 | Table S2 in Borges et al. (23) | 19.8–36 | 33.60–1,722.00 | 68.60–7,526.40 | 0.168–0.913 |

| Betsiboka | 2010–2012 | Table S2 in Borges et al. (23) | 17.3–30.7 | 36.40–291.20 | 1.40–173.60 | 0.171–0.384 |

| Rianila | 2010–2012 | Table S2 in Borges et al. (23) | 16.8–29.3 | 42.00–207.20 | 1.40–149.80 | 0.190–0.303 |

| Tana | 2010 | Table S2 in Borges et al. (23) | 22.6–27.5 | 11.20–85.40 | 389.20–1,843.80 | 0.190–0.350 |

| Zambezi | 2010 | Table S2 in Borges et al. (23) | 16.9–30.7 | 1.40–410.20 | 1.40–632.80 | 0.162–0.319 |

| Congo | 2010–2013 | Table S2 in Borges et al. (23) | 22.3–29.4 | 4.20–207.20 | 4.20–862.40 | 0.165–0.381 |

| Hudson | 1998–1999 | Urban; Cole and Caraco (24) | 20–25.9 | 2.41–142.82 | 292.31–541.81 | 0.248–1.043 |

| Manistee | 2014 | Forest | 11–21.5 | 0.25–59.12 | 4.81–2,803.80 | 0.209–0.586 |

| Tippecanoe | 2014 | Agricultural | 15.5–28 | 3.59–624.35 | 13.04–4,515.88 | 0.274–2.571 |

| Swale-Ouse | 1995–1996 | Mainly agricultural (22) | 10.52–19.59 | 11.15–504.89 | 9.36–13,126.36 | nda |

| LINXII Study | 2003–2005 | Table S1 in Mulholland et al. (10) | 9.9–23 | 3.00–2,204.00 | 35.00–4,158.00 | ndb |

| Kalamazoo | 2004–2005 | Table 1 in Beaulieu et al. (19) | nd | 5.00–95.00 | 30.00–21,760.00 | ndc |

Results and Discussion

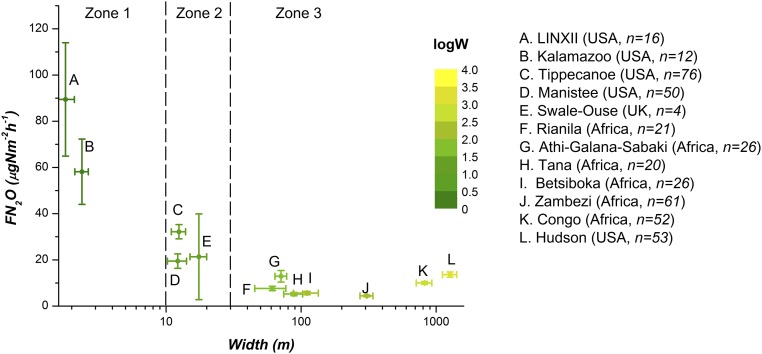

Analysis of average flux of emissions per unit area, (micrograms N per square meter per hour), from the study reaches of all of 417 analyzed streams and rivers to the atmosphere shows that systematically decreases with system size (as width) along a gradient from headwater streams to rivers (Fig. 1) of contrasting river networks (e.g., US streams and African rivers) and within the same networks (e.g., Manistee and Tippecanoe, with channel widths that span 1 to >50 m) (Table S2). Using this analysis, streams and rivers can be classified in three zones according to the gradient of reduction in emissions shown in Fig. 1. Zone 1, which includes small streams with widths () that are less than 10 m (4), shows a very steep reduction of emissions with stream size. Zone 2, which includes streams with 10 30 m, has a gradual reduction of emissions with stream size, and zone 3 groups rivers with 30 m and emissions that do not depend on . These proposed breaks are similar to those reported in the stream geomorphological literature (26, 27), suggesting the importance of stream hydromorphological characteristics for determining the biogeochemistry of streams/rivers (details are in SI Text). We hypothesized that this reduction is caused by a shift from production that occurs primarily in the benthic and hyporheic zones (benthic–hyporheic zone) of headwater streams to production occurring in the benthic zone and the water column (benthic–water column zone) of rivers, and this shift is caused by a reduction in hyporheic exchange rate with increasing stream/river discharge flows.

Fig. 1.

Nitrous oxide emissions from the analyzed streams and rivers. Average emissions () per unit area as a function of the mean system width () for the analyzed streams and rivers. Zone delineation is based on changes with stream/river size (fast change with size for zone 1, low change with size for zone 2, and no change with size for zone 3). This division is consistent with the classification proposed by the Forest Practice Code (26), Buffington and Montgomery (27), and Peterson et al. (4). Error bars represents the SE () of the mean stream width and average flux of .

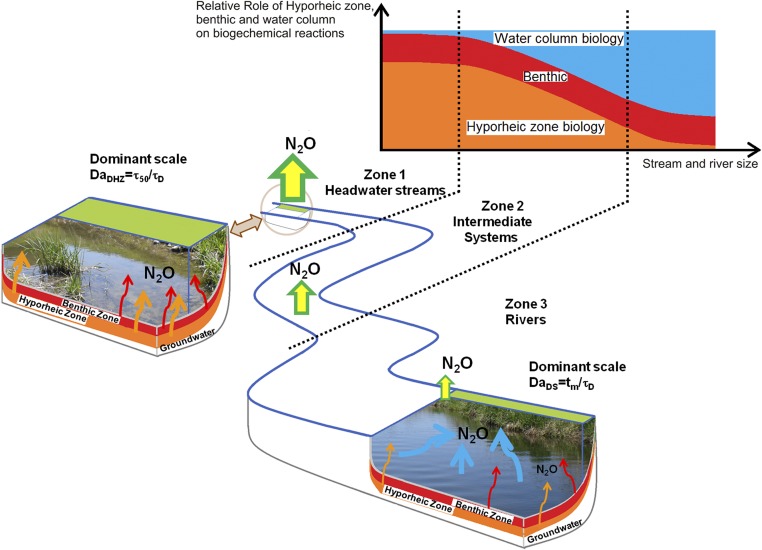

The work of Ocampo et al. (15) suggested interpreting transport and transformation within a riparian zone using a Damköhler number, which is the ratio of a characteristic residence time, with importance (28) that has been documented by several empirical (5, 16, 17) and numerical (29, 30) investigations, to the characteristic time of the pertinent biogeochemical reaction. Recent investigations also proposed this approach to interpret hyporheic processes (31, 32), and they adapted it to quantify the hyporheic biogeochemical response at both bed-form (33) and reach (34) scales. Here, we capitalized on these advances to depict the observed scaling effect on emissions across riverine networks (Fig. 1), and we parameterized the transformation efficiency of dissolved to gaseous in terms of two Damköhler numbers (Materials and Methods and SI Text). In headwater streams that are typically small and shallow, microbially mediated denitrification occurs mainly within the benthic–hyporheic zone (35). Headwater stream hydrodynamics at and within the streambed (hyporheic flows) is the main factor controlling the flux of dissolved nutrients to the microbial assemblages that control biogeochemical transformations (Fig. 2). Therefore, the Damköhler number for the benthic–hyporheic zone is defined as the ratio between the median hyporheic residence time (), which is an index of the time that stream water spends within the hyporheic sediment, and the characteristic time of denitrification (), , where is the denitrification reaction rate (evaluated as the ratio between the denitrification uptake rate, , and the mean flow depth, : ): (zone 1 in Fig. 2) (36). However, as stream size increases, the ratio of hyporheic to surface flow declines, which reduces the relative contribution of hyporheic zone to biogeochemical transformations (zone 2 in Fig. 2). In rivers, therefore, water column transformations combined with benthic processes at the sediment–water interface dominate denitrification, overwhelming the benthic–hyporheic contribution (zone 3 in Fig. 2). This behavior requires a different metric to describe the relevant timescale of production. We identify this metric with the time of turbulent vertical mixing, , which is the average time for any neutrally buoyant particle to sweep through the entire water column because of turbulence. Thus, we introduce a unique Damköhler number for rivers, , with replacing and stating a shift from hyporheic- to water column-dominated production.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model describing the relative role of hydrodynamics and biogeochemical transformations within three zones of increasing stream size. Size of arrows indicates the magnitude of emissions per unit area from streams and rivers and the relative importance of water column (light blue), benthic (red), and hyporheic (orange) zones as sources of .

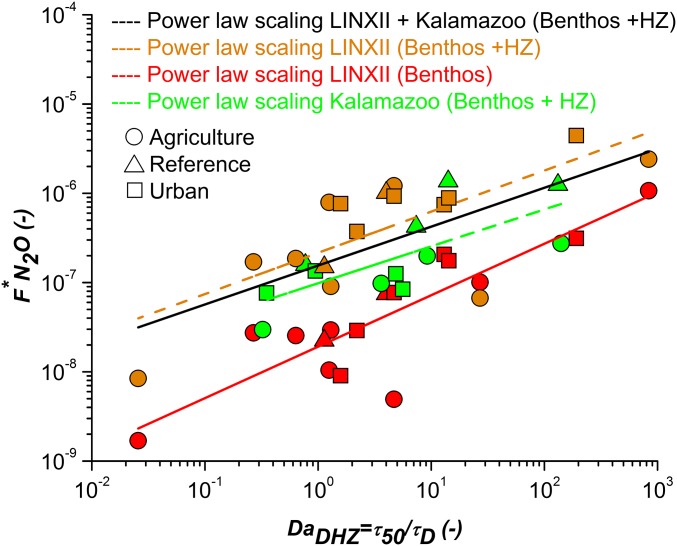

Similar to our previous work (34), we define the dimensionless flux of , , as the ratio between and the total flux per unit streambed area of dissolved inorganic nitrogen species [ and ammonium ()] in the stream (). Both reactive species are potential sources of via denitrification and nitrification, respectively (37), and may vary with time and stream (11) (Eq. S18). Moreover, dimensionless emissions depend on the inorganic nitrogen load through , which is often parameterized as a function of the stream concentration of (19, 20). The use of isotopic tracer along the LINXII Study sites (6, 10, 11) allows for separating production from the benthic and hyporheic zones, with the former associated with direct denitrification and the latter associated with the indirect one (6, 34) (SI Text). Furthermore, groundwater and water column contributions from these headwater systems were deemed negligible at the LINXII Study sites (6). Measured emissions from only the benthic zone (Fig. 3, red symbols) are one order of magnitude lower than the total emissions from both benthic and hyporheic zones (Fig. 3, orange symbols), stating the relative importance of the hyporheic zone contribution in headwater streams (zone 1 in Fig. 2). The power law relationships reported in Fig. 3 shown by red and orange lines are obtained by regression with the experimental LINXII Study data and suggest that hydromorphological processes governing hyporheic exchange also influence processes within the benthic zone. They have similar scaling patterns, with experimental data ranging more than five log scales regardless of biome, LULC type, stream morphology, stream size, and climatic conditions (Fig. 3) and effects that are accounted in the proposed dimensionless framework via , , and , with linked to biochemistry and linked to stream hydraulic and morphology (34, 36) (Materials and Methods and SI Text). This linkage confers predictability to the above relationships provided that is known. The same analysis applied to flux from the benthic–hyporheic zone in the Kalamazoo River watershed (19, 20) shows a similar scaling with for (Fig. 3, green dashed line), which is not statistically different from the orange line in Fig. 3 [analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) analysis and ]. Thus, we combine the LINXII Study and Kalamazoo River data and define the following power law (black solid line in Fig. 3): and , which we identify as the upper emission potential (upper bound) from headwater streams caused by processes occurring in both the hyporheic and benthic zones, whereas the production from only the benthic zone provides the lower emission potential (lower bound) (red solid line in Fig. 3). We expect that these two dimensionless power laws are globally applicable at the watershed and larger scale, because the use of captures both the advective and biogeochemical scaling of production at the reach scale, whereas the effect of water temperature can be accounted for with an Arrhenius-like relationship when quantifying the flux from . We test their generality with all study reaches (more than 400 worldwide), excluding those used in their derivation (LINXII Study, 16 streams, and Kalamazoo River, 12 streams). Therefore, emissions from headwater streams in zone 1 within a riverine network (compare Figs. 3 and 4A) can be computed as the product of the total mass flux of inorganic nitrogen load () and provided by the upper-bound power law model as a function of (black line in Fig. 3). We found this power law valid for all of the headwater streams of the watersheds analyzed in this study regardless of biomes, LULC, or climatic conditions (in Fig. 4A, notice the higher of 0.59 when applied for all studied headwater streams without including those used to derive the upper-bound power law relationship in Fig. 3). The regression of a power law to all of the available data (blue line in Fig. 4A) is also not statistically different (ANCOVA analysis and ) from the upper-bound power law (black lines in Figs. 3 and 4A) and maintains the same . Thus, we suggest that the upper-bound power law could be widely applicable to streams across the globe because of the breath of our data. Some unexplained variance is likely caused by originating from groundwater and terrestrial sources or nitrification/denitrification of groundwater . Our model assumed that the main source of resulted from transformations of dissolved inorganic nitrogen ( plus ) present in the stream without distinguishing the source of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (e.g., groundwater, runoff, or atmospheric deposition). As such, we may partially account for of groundwater origin if nitrification occurs within the stream via transformation in the water column, benthic, or hyporheic zone. Another potential source of error is that we do not account explicitly for hyporheic downwelling fluxes that control the amount of reactants delivered to the sediment. These fluxes depend on the same hydromorphological parameters that characterize , and thus, we implicitly, although partially, account for downwelling fluxes via , because there is an inverse relationship between and mean hyporheic downwelling flux.

Fig. 3.

Dimensionless flux of () as a function of the denitrification Damköhler number () in the LINXII Study (, ) and the Kalamazoo River (Michigan; ) streams. resulting from the production of within only the benthic zone of the LINXII Study streams is shown with red symbols; the power law regression of these data is shown with the red solid line []. Emissions from the benthic–hyporheic zone (combined contribution of both zones, Benthos + HZ) are in orange symbols, and their power regression is shown as the orange dashed line []. Emissions from the benthic–hyporheic zone of the Kalamazoo streams scale with [] as shown by the green line. Because these two relationships (dashed orange and green lines) are not significantly different, we fitted both datasets with a power law [; black line], which quantifies emissions from headwaters.

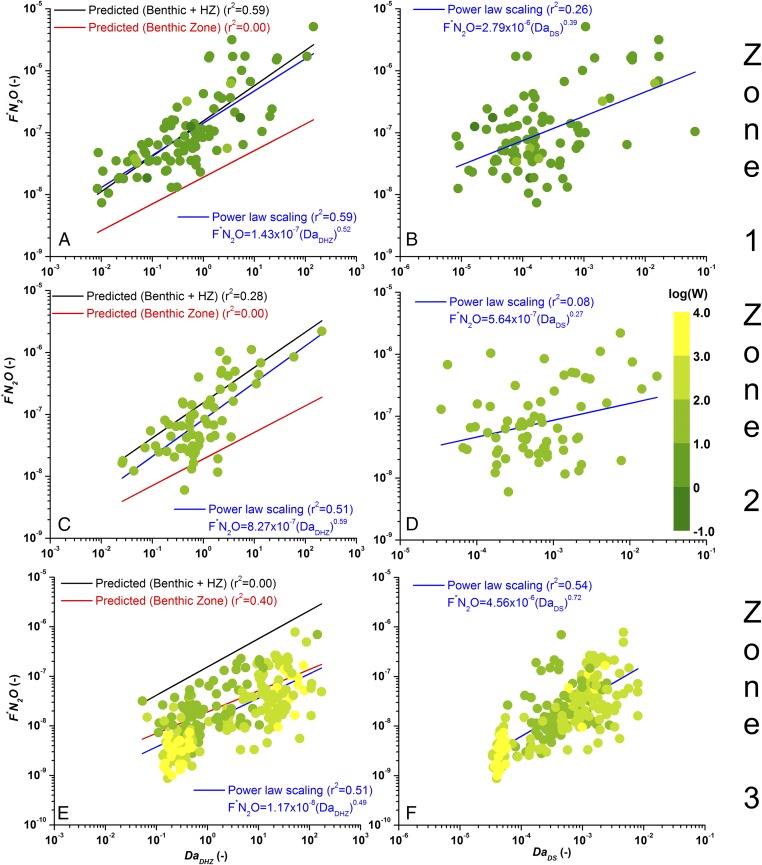

Fig. 4.

Dimensionless flux of () as a function of the two Damköhler numbers, reflecting processes occurring within the benthic–hyporheic zone and the water column. None of the streams (circles), shown colored by reach width with the width increasing from green to yellow, were used in deriving the upper (black lines) and lower bounds (red lines) in A, C, and E. A, C, and E consider the scaling of as a function of for zones 1–3, respectively. Black lines represent the scaling obtained in Fig. 3 by fitting the power law to the LINXII Study and Kalamazoo River data [ number of streams, 28; ]. Red lines represent the scaling obtained by fitting the power law to the LINXII Study data ( 16) considering only benthic emissions (red line in Fig. 3) [], and blue lines represent the fitting of the power law with all of the data shown. B, D, and F show the scaling of as a function of for zones 1–3 ( 91, 66, and 247, respectively). The blue continuous lines represent the fitting of a power law with all of the data shown by circles in the graph.

As stream/river size increases, the relative contribution of the hyporheic zone to emissions in relation to the benthos and water column declines; consequently, our conceptual model predicts a decline in dimensionless emissions, (compare Fig. 4 A, C, and E). Notice that colors of the symbols in Fig. 4 vary from green to yellow as the width of the system increases from streams to rivers. The coefficient of determination of the upper-bound power law model, which includes both benthic and hyporheic zones (in Fig. 4, the black lines are the same as in Fig. 3), declines moving from headwater streams (Fig. 4A, ) to intermediate systems (Fig. 4C, ) and rivers (Fig. 4E, ). This decrease suggests a shift in processes controlling production. When the data are fitted, rises again, but the resulting regression curves, shown in blue in Fig. 4 C and E, increasingly deviate from the power law model of zone 1 (upper bound) (black line in Fig. 3) as stream and river size increases (moving from Fig. 4 A, C, and E) and approaches the lower-bound power law model (Fig. 3, red line with of 0.40 when applied for all studied rivers, of which none were used for its derivation). The fitted blue line in Fig. 4E and the lower-bound power law (red line in Fig. 4E), which was derived without the contribution of the hyporheic zone (Fig. 3), are not statistically different (ANCOVA analysis and ), which suggests that hyporheic processes have a negligible contribution to emissions in rivers. Conversely, a power law, , where , encapsulating hydrodynamic and biochemical processes occurring in the benthic–water column environment, replaces fitted to the experimental data separately (Fig. 4 B, D, and F), shows very low-determination coefficients in headwater and intermediate systems (Fig. 4 B, and D, ) but a value comparable with that in Fig. 4A for rivers ( in Fig. 4F). Consequently, emissions from rivers scale with (which is defined by replacing the hyporheic residence time with the residence time in the water column) better than with (compare Fig. 4 E and F).

We suggest that the contribution of the water column to emissions increases from streams to rivers as an effect of an increase in suspended particle loads. Denitrification has been shown to occur within anoxic microsites associated with suspended sediments located throughout the well-mixed water column (38) typical of river systems. Contrary to existing modeling and empirical approaches (12, 34, 36), which suggest that the hyporheic zone or benthos is the primary source of regardless of stream and river size, our data show a systematic shift from predominantly hyporheic–benthic production in streams to predominantly benthic–water column production in rivers.

Using a metaanalysis of all available data collected by us and previously published, we show that this shift is controlled by key hydrodynamic and biogeochemical parameters that effectively explain the observed decline of emissions per unit area as the stream/river size increases. We used hydrodynamic parameters typically collected in the field for morphologic classification: the reach-scale mean flow velocity (), the hydraulic depth (), the mean channel width (), the channel slope (), the median grain size (), and the type of bed forms. When not measured or observed in the field, we estimated these quantities by means of morphological relationships as a function of drainage area and water discharge (39–41) (Table S5) or using information extracted from remote sensing and Digital Terrain Map analysis (chiefly for and ). In addition, we used morphological relationships on bed-form stability to characterize bed-form morphology and (42, 43) when not observed in the field. Successively, we used these parameters to quantify (Eq. S1) or (Eq. S4 shows dune morphology, and Eq. S7 shows pool-riffle morphology). The biogeochemical parameters are , which we evaluated in the field or derived from concentrations measurements (Table S3), and and concentrations. All of these quantities vary among reaches belonging to the same river system as noted in Tables S2 and S3, which report the minimum and maximum values for each river system as well as the variability of and , which depends on variation in morphological and biogeochemical parameters (Table S3). This variability results from natural variation in both hydraulics and biogeochemical parameters among reaches and may explain, at least partially, the scatter observed in Figs. 3 and 4, but it does not represent the effect of parameter uncertainty or within-reach variability, which we do not consider here. emissions per unit area are predictable and greater, for a given nutrient load, in headwater streams compared with rivers, in part because of the contribution of the hyporheic zone. Headwater streams are important sources of emissions along riverine networks resulting from a combination of significant contact time with the bioreactive benthic–hyporheic zone and significant surface–subsurface exchange of water and solutes (4, 18) as well as their relative predominance in river networks. In contrast, as streams transition to rivers, the contribution of the hyporheic zone declines, and benthic–water column contribution dominates. Thus, headwater streams may have a disproportionate impact on annual emissions, especially if they drain agricultural or urban LULC type, because they also represent the greatest proportion of riverine network drainage length (4).

Table S5.

Scale factors , , and and exponents , , and for the power law relationships relating hydraulic geometry parameters in the analyzed streams and rivers with different values of the watershed drainage area

| River name | WDA (km2) | Source | a | b | c | d | e | f |

| AGS | 40,300a | Smokey Hill River in Rhoads (40) | 10.79 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.171 | 0.12 |

| Betsiboka | 68,311a | James River in Rhoads (40) | 7.47 | 0.49 | 0.62 | 0.30 | 0.215 | 0.21 |

| Congo | 3,705,222a | Missouri River in Rhoads (40) | 14.1 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.134 | 0.08 |

| Hudson | 33,500b | Raymond et al. (41) | 12.936 | 0.423 | 0.408 | 0.294 | 0.194 | 0.285 |

| Manistee | 3,616 | Raymond et al. (41) | 12.936 | 0.423 | 0.408 | 0.294 | 0.194 | 0.285 |

| Rianila | 7,844a | Raymond et al. (41) | 12.936 | 0.423 | 0.408 | 0.294 | 0.194 | 0.285 |

| Swale-Ouse | 3,200c | Raymond et al. (41) | 12.936 | 0.423 | 0.408 | 0.294 | 0.194 | 0.285 |

| Tana | 100,608a | Missouri River in Rhoads (40) | 14.1 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.134 | 0.08 |

| Tippecanoe | 4,496 | Raymond et al. (41) | 12.936 | 0.423 | 0.408 | 0.294 | 0.194 | 0.285 |

| Zambezi | 1,378,102a | Missouri River in Rhoads (40) | 14.1 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.134 | 0.08 |

We unveiled the primary scaling factors governing riverine emissions and provide a predictive tool that can be applied worldwide to quantify emissions from riverine environments across scales from headwater streams ( ) to rivers ( ) draining a variety of biomes, LULC types, and climatic conditions through accessible reach-scale geochemical measurements (i.e., stream temperature and concentration) and hydromorphological parameters (i.e., stream morphology, mean flow depth, velocity, slope, and channel width) (SI Text). Our scaling laws allow one to quantify emissions at the watershed scale using geographic information system analyses of stream morphology (44) and readily available measurements of nitrate and ammonium, which can be distributed throughout the river network, both in space and through time (45). This approach requires robust hyporheic models linked to hydromorphological information. These models are not currently available for cascade, step-pool, and plane-bed morphologies (34), which are common in small headwater streams (27). Consequently, there is a need for research to define these relationships, include them in network-scale hyporheic models, and quantify Da numbers, such as in the project Networks with Exchange and Subsurface Storage (12) to predict reach-scale emissions. Furthermore, the above evidences of the role of river morphology in controlling emissions may contribute to improvement of conceptual models by considering stream morphology and constraining and linking the role of the different parts of the stream/river reach (e.g., hyporheic zone, benthic zone, the water column, and also the riparian zone). This scaling framework actively quantifies the impact of human activity and natural forcing through , a function of river morphology and hydrology (46), which may change because of climate change, water extraction, sediment transport regime, and land use, and , which accounts for land use land cover, and therefore, water quality. Water temperature effects on emissions can be also accounted by scaling the dimensionless value with an Arrhenius-type equation. Thus, the framework can be used to quantify emissions under different scenarios and treatments, such as watershed-scale changes in land use and water management or how changing climate influences biogeochemical outcomes. Consequently, it provides the needed feedback among climate, LULC, and water management to help quantify human impact on climate change at the global scale.

Materials and Methods

The dimensionless flux of from riverine networks is parameterized with a Damköhler number that represents the ratio between the characteristic residence time within the denitrifying zones (benthic, hyporheic, and water column) and the characteristic time of the biogeochemical reaction. For the purpose of this model, the characteristic time of the biogeochemical reaction is the time of denitrification, , and it is defined as the inverse of the denitrification reaction rate () (details on the calculation of are in SI Text), whereas the characteristic residence time within the denitrifying zones changes along the riverine network according to the riverine environments that mainly control this biogeochemical process.

In headwater streams, a robust estimator of the time that a solute molecule is exposed to the denitrifying environment is the median hyporheic residence time (), which is the time at which 50% of stream water that entered the streambed sediment is still within the hyporheic zone. Its value is a function of streambed morphology, surface hydraulics, and groundwater table (details on the calculation of are in SI Text). Consequently, it accounts for the impact of external forcing on stream physical conditions, such as human water management, or climate change on discharge and sediment transport. Changes in both discharge and sediment input caused by climate change affect bed-form type and shape. This forcing also includes LULC, biome, and climatic conditions. Therefore, the Damköhler number for the benthic–hyporheic zone is defined as the ratio between the characteristic time controlling hyporheic residence time and the characteristic time controlling the denitrification process:

| [1] |

Values of suggest that the system is limited by the denitrification rate (i.e., low ) or short residence time (small ). Conversely, suggests high denitrification efficiency (high ) or long residence time (large ) (zone 1 in Fig. 2).

As stream size increases, the ratio of hyporheic to surface flow declines in favor of a gradual contribution of the benthic–water column in controlling denitrification (zone 2 in Fig. 2). Rivers are turbulent systems in which dissolved solutes and particles are vertically mixed throughout the water column (47), thus requiring a different metric to describe the relevant timescale of production. We identify this metric with the time of turbulent vertical mixing, , which is the average time for any neutrally buoyant particle to sweep through the entire water column because of turbulence (details on the calculation of are in SI Text). Thus, we introduce a unique Damköhler number for rivers as follows:

| [2] |

where the median residence time in the hyporheic zone, , is replaced by , stating a shift from hyporheic- to water column-dominated production. When (), the timescale for the vertical mixing is less than that of denitrification; therefore, the production of is chiefly controlled by microbial activity. In contrast, when (), the production of is controlled by hydrodynamics, which determines solute mixing throughout the water column, thereby influencing the contact time with microbial denitrifiers carried by suspended particles.

All data reported in the paper are reported in SI Text.

SI Text

Characteristics of Analyzed Streams and Rivers.

The Manistee River, included in the federal registry of National Wild and Scenic Rivers, is forested over 83% of its 3,616-km2 watershed, whereas the Tippecanoe River, also considered one of the “top-10 rivers that must be preserved” by The Nature Conservancy, has 82% of its 4,496-km2 watershed in intensive row crop agriculture. The contrasting LULC types between these two watersheds are reflected in seasonal and annual patterns of discharge, temperature regimes, and inorganic N loading, with average concentration at 120 gN/L in the Manistee River and 1,860 gN/L in the Tippecanoe River during summer base flow conditions. During summer, stream discharges range between 22 and 14,000 L/s in the Manistee River and between 2.5 and 22,500 L/s in the Tippecanoe River from the headwaters to the main stem. In the Kalamazoo River (Michigan) watershed, data are available from 12 small headwater streams ( L/s) draining three different LULC types [i.e., agriculture, urban, and reference (unmodified LULC)] (19, 20). These sites are composed of low-gradient streams dominated by fine sediments and sand (20) with dune-like and pool-riffle morphologies. The LINXII Study dataset includes 16 headwater streams from six different US biomes across three different LULC types (agriculture, urban, and reference) characterized by two different types of morphology: pool riffle and dune (6, 10, 34). In these headwater systems, experimental results confirm that production within the water column is negligible (6, 35). We were able to use 16 of 72 LINXII Study streams that included geomorphic site characterization, which allowed us to characterize the flux of and/or the median hyporheic residence time. Of the remaining sites, 29 had missing emission or production rates [table S1 in the work by Beaulieu et al. (6)], whereas the remaining 30 sites had step-pool, cascade, or undefined morphology for which there are no hyporheic flow models to provide a robust estimate of the median hyporheic residence time () [discussion of figure 2 in the work by Marzadri et al. (34)]. We also used previously published data collected at five locations along the Swale-Ouse River (United Kingdom) from headwater (steep reach characterized by boulders, cobble, and sand) to tidal sites (low gradient and mainly sand-bedded reach) and at one site of a highly eutrophic tributary, the Wiskle River (21, 22). The mean annual discharge of the Swale-Ouse is 5,600 L/s, and the LULC is mainly agriculture (42% arable and 23% pasture). The six large river networks in sub-Saharan Africa are characterized mainly by three different LULC: grassland [Athi–Galana–Sabaki (AGS), Betsiboka, and Tana], forest (Rianila and Congo), and woodland and shrubland (Zambezi) (23). Their mean annual discharges range from 72,000 L/s in the AGS to 41,000, 127 L/s in the Congo. The lower part of the Hudson River is a tidal system flowing in the urban area between Albany and Manhattan, with a mean annual discharge of 400,000 L/s (24, 25). We categorize all of the streams and rivers into three zones according to estimated width , and we categorized channel sizes as small with 10 m, intermediate systems with , and large rivers with 30 m. Our analysis (Fig. 1) shows that emissions decrease rapidly with in zone 1, decrease slowly in zone 2, and remain constant in zone 3, which are in agreement with previous characterizations. In the Forest Practice Code (26), streams are classified as small and intermediate with m and rivers are classified with m, whereas in the work by Buffington and Montgomery (27), small streams have width m, intermediate streams have m, and large rivers have m. Compared with these classifications, we reduce the width limit for small streams to m according to the work by Peterson et al. (4).

Characterization of the Timescale of Vertical Mixing.

The timescale of vertical mixing is given by the following expression: , where represents the length scale of vertical mixing, and is the vertical turbulent diffusion coefficient (47), which can be evaluated through the following expression (48): ; is the shear velocity, where is the gravitational acceleration and is the friction slope (47). Consequently, the characteristic time becomes

| [S1] |

The friction slope is evaluated using the Manning’s formulation under the assumption of uniform flow condition in a wide channel:

| [S2] |

where is the mean flow velocity.

If not measured, the reach-scale mean width , depth , and velocity are evaluated by using the following power law relationships (39):

| [S3] |

where the scale factors , , and and the exponents , , and depend on watershed drainage area . For watersheds with 35,000km2, we used the parameters reported by Raymond et al. (41), and we used those by Rhoads (40) for watersheds with 35,000km2 (Table S5). Both measured and computed (through Eq. S3) reach-scale hydraulics are reported in Tables S1 and S2.

Characterization of the Median Hyporheic Residence Time.

The median hyporheic residence, , was evaluated for dune and pool-riffle morphology according to formulations presented in a previous work (34) by assuming steady-state flow conditions in both the stream and hyporheic zone and neutral groundwater–stream interaction (no losing or gaining conditions). Hydraulic conductivity of the alluvium, which was used to compute , is assumed homogeneous within the following range: depending on (49), if available, or streambed sediment texture (Table S2 reports the range of variation of all of the hydromorphologic parameters used to evaluate ). Streams and rivers included in the LINXII Study experiment and the following stream/rivers (Kalamazoo, Manistee, Tippecanoe, and Swale-Ouse) are characterized with dune or pool-riffle morphology according to the available information on stream slope () and median grain size () and where possible (the LINXII Study, Manistee River, and Tippecanoe River), by visual inspection. African rivers and the Hudson River are assumed to be characterized by dune morphology according to the values of stream slope evaluated from Eq. S2. For streams characterized by dune morphology, the value of is evaluated according to the formulation proposed and validated by Elliott and Brooks (50):

| [S4] |

where is the bed-form wavelength [with being the bed-form length evaluated according to Yalin (42)], is the alluvium hydraulic conductivity, and is the amplitude of head variation, which depends on stream hydrodynamic parameters through the following equation reported by Shen et al. (51):

| [S5] |

where is the gravitational acceleration and is the bed-form height, which is assumed equal to according to Yalin (42). Therefore, according to Eqs. S4 and S5 and given that , under the hypothesis that and (42), assumes the following expression:

| [S6] |

For streams characterized by pool-riffle morphology, is evaluated according to the formulation proposed and validated by Marzadri et al. (33):

| [S7] |

where is the bar length, is the dimensionless Chezy coefficient quantifying streambed resistance (Eq. S9), and is the dimensionless streamflow depth that depends on the pool-riffle height according to the following expression proposed by Ikeda (43):

| [S8] |

where is the alternate bar aspect ratio and is the relative submergence. Furthermore, streambed resistance is estimated through the following relationship:

| [S9] |

According to Eqs. S7–S9, and and under the hypothesis that , assumes the following expression:

| [S10] |

According to Eq. S1 and with , assumes the following expression:

| [S11] |

Characterization of the Residence Time of Denitrification.

We estimated for each stream and river based on data availability, which ranged from direct measurements to reported values of and to directly measured concentrations. We scaled with , because the mean hydraulic depth is a critical parameter for both stream and hyporheic hydraulics; both dune and pool-riffle bed-form hyporheic exchanges depend on . Table S3 reports the different formulations adopted to evaluate the uptake rate of denitrification when is not measured directly. For the African rivers and the Hudson River, where no information was available on , we used the empirical formulations proposed by Mulholland et al. (10) (Eq. S19), from which is quantified from stream concentrations. For the Manistee River and the Tippecanoe River, we used a modified version of the relationship proposed by Mulholland et al. (10), where we considered only eight LINXII Study streams in Michigan located midway between our studied watersheds (Eq. S20). For the Kalamazoo River (Michigan) and the Swale-Ouse River (United Kingdom), we estimated using their measured values of the areal uptake rate of denitrification () and the stream nitrate concentration (; Eq. S21 for the Swale-Ouse River and Eq. S23 for the Kalamazoo River). Finally, for the LINXII Study streams, is evaluated as the inverse of the measured values of the reaction rate of denitrification reported in the work by Beaulieu et al. (6) (Eq. S22).

Characterization of Nitrous Oxide Production from Benthic and Benthic–Hyporheic Zones in the LINXII Study Streams.

In the LINXII Study sites, isotopic tracer experiments have been used to measure direct denitrification occurring in the benthos (term B in Eq. S12). Here, we used this information to separate it from the total emissions (emission rate) (term A in Eq. S12) (6) to estimate the produced by denitrification within the hyporheic zone () (term C in Eq. S12):

| [S12] |

The missing production of that resolves the mass balance is a combination of indirect denitrification ( to to ) and denitrification that occurs in groundwater before reaching the stream and the hyporheic zone [called “from unmeasured sources” in the work by Beaulieu et al. (6)]. Available data do not allow us to separate the different contributions responsible for indirect denitrification. However, Marzadri et al. (34) proposed that, because of the short duration of the experiments, the LINXII Study measurements did not characterize coupled nitrification–denitrification, and therefore, the first contribution was deemed equal to zero; therefore, they are, in principle, conservative estimates of production via denitrification, and the contribution of groundwater was shown to also be negligible in the LINXII Study streams (6), such that the “unmeasured sources” portion equals the production within the hyporheic zone (34). In Fig. 3, the lower emission potential is quantified by using only the dimensionless flux of resulting from the production within the benthos (direct denitrification), whereas the upper emission potential is quantified by using the measured total emissions (direct and hyporheic denitrification). For the upper emission potential, we also used the data reported by Beaulieu et al. (19, 20) measured along the Kalamazoo River.

Evaluation of Nitrous Oxide Emissions.

The emitted to the atmosphere via diffusive evasion (micrograms N per square meter per hour) is evaluated as follows:

| [S13] |

where is the air–water gas exchange rate (), is the measured concentration of dissolved nitrous oxide in the stream water (micrograms N per liter), and is the concentration expected if the stream was in equilibrium with the atmosphere (micrograms N per liter). In all of the streams and rivers analyzed, was measured. Except for the Swale-Ouse River (22), the LINXII Study (6) streams, and the Kalamazoo River (19, 20), where was directly measured, was calculated using Eq. S13. For these rivers, is computed by using the Henry’s law:

| [S14] |

where () are constants (9), is the water temperature (Kelvin), is the partial pressure of in the air (atm), and is the molecular weight of as N. For the Hudson River, the values of were measured (24), whereas for the other streams and rivers, we assumed a partial pressure of (6). The air–water gas exchange rate () is quantified as follows (52):

| [S15] |

where is a coefficient that should be or depending on surface state of water; we fixed it equal to considering low wind speed (52) along the Manistee River, the Tippecanoe River, and the Swale-Ouse River (United Kingdom) and along all of the African rivers and the Hudson River considering the presence of waves at the air–water interface. The variable (meters per day) is the gas transfer velocity evaluated according to model 5 proposed by Raymond et al. (41):

| [S16] |

for all of the rivers except for the Hudson River, along which we used a mean value of (m/d) (25). This choice is justified by the fact that measurements have been taken in the part of the river influenced by tide effects. In Eq. S15, is the Schmidt number of evaluated as a function of water temperature (degrees Celsius) as follows (53):

| [S17] |

Following Marzadri et al. (34), we define the dimensionless flux of , , as the ratio between the stream emissions to the atmosphere, , and the total stream mass flux of and , which are the potential sources of and may vary with time and stream (11):

| [S18] |

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by National Science Foundation Awards 1344661 and 1344602 and by the European Communities 7th Framework Programme under Grant Agreement 603629-ENV-2013-6.2.1-Globaqua. Any opinions, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the supporting agencies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617454114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Syakila A, Kroeze C. The global nitrous oxide budget revisited. Greenhouse Gas Meas Manage. 2011;1:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey JW, Böhlke JK, Voytek MA, Scott D, Tobias CR. Hyporheic zone denitrification: Controls on effective reaction depth and contribution to whole-stream mass balance. Water Resour Res. 2013;49:6298–6316. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seitzinger SP. Denitrification in freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems: Ecological and geochemical significance. Limnol Oceanogr. 1988;33:702–724. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson B, et al. Control of nitrogen export from watershed by headwater streams. Nature. 2001;292:86–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1056874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarnetske JP, Haggerty R, Wondzell SM, Baker MA. Dynamics of nitrate production and removal as a function of residence time in the hyporheic zone. J Geophys Res. 2011;116:G01025. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaulieu JJ, et al. Nitrous oxide emission from denitrification in stream and river networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:214–219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011464108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boano F, et al. Hyporheic flow and transport processes: Mechanisms, models, and biogeochemical implications. Rev Geophys. 2014;52:603–679. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosamond MS, Thuss SJ, Schiff SL. Dependence on riverine nitrous oxide emissions on dissolved oxygen levels. Nat Geosci. 2012;5:715–718. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss RF, Price BA. Nitrous oxide solubility in water and seawater. Mar Chem. 1980;8:347–359. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulholland PJ, et al. Stream denitrification across biomes and its response to anthropogenic nitrate loading. Nature. 2008;452:202–206. doi: 10.1038/nature06686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall RO, et al. Nitrate removal in stream ecosystems measured by 15N addition experiments: Total uptake. Limnol Oceanogr. 2009;54:653–665. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez-Velez JD, Harvey JW. A hydrogeomorphic river network model predicts where and why hyporheic exchange is important in large basins. Geophys Res Lett. 2014;41:6403–6412. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkiteswaran JJ, Rosamond MS, Schiff SL. Nonlinear response of riverine fluxes to oxygen and temperature. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:1566–1573. doi: 10.1021/es500069j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner PA, et al. Indirect nitrous oxide emissions from streams within the US Corn Belt scale with stream order. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:9839–9843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503598112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ocampo CJ, Oldham CE, Sivapalan M. Nitrate attenuation in agricultural catchments: Shifting balances between transport and reaction. Water Resour Res. 2006;42:W01408. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu CH, Hornberger GM, Mills AL, Herman JS, Flewelling SA. Nitrate reduction in streambed sediments: Effects of flow and biogeochemical kinetics. Water Resour Res. 2007;43:W12413. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinay G, O’Keefe TC, Edwards RT, Naiman RJ. Nitrate removal in the hyporheic zone of a salmon river in Alaska. River Res Appl. 2009;25:367–375. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander RB, Smith RA, Schwarz GE. Effect of stream channel on the delivery of nitrogen to the Gulf of Mexico. Nature. 2000;403:758–761. doi: 10.1038/35001562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beaulieu JJ, Arango CP, Hamilton SK, Tank JL. The production and emission of nitrous oxide from headwater streams in the Midwestern United States. Glob Chang Biol. 2008;14:878–894. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaulieu JJ, Arango CP, Tank JL. The effects of season and agriculture on nitrous oxide production in headwater streams. J Environ Qual. 2009;38:637–646. doi: 10.2134/jeq2008.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pattinson SN, García-Ruiz R, Whitton BA. Spatial and seasonal variation in denitrification in the Swale-Ouse system, a river continuum. Sci Total Environ. 1998;210/211:289–305. [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Ruiz R, Pattinson SN, Whitton BA. Nitrous oxide production in the river Swale-Ouse, North-East England. Water Res. 1999;33:1231–1237. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borges AV, et al. Globally significant greenhouse-gas emissions from African inland waters. Nat Geosci. 2015;8:637–642. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole JJ, Caraco NF. Emissions of nitrous oxide () from a tidal, freshwater river, the Hudson river, New York. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:991–996. doi: 10.1021/es0015848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caraco NF, et al. Zebra mussel invasion in a large, turbid river: Phytoplankton response to increased grazing. Ecology. 1997;78:588–602. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forest Practice Code . Channel Assessment Procedure Field Guidebook in Forest Practice Code. British Columbia Ministry of Forest; Vancouver: 1996. pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buffington JM, Montgomery DR. Geomorphic classification of rivers. In: Shroder J, Whol E, editors. Treatise on Geomorphology. Academic; San Diego: 2013. pp. 730–767. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gooseff MN. Defining hyporheic zones Advancing our conceptual and operational definitions of where stream water and groundwater meet. Geogr Compass. 2010;4:945–955. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardenas MB, Cook PLM, Jiang H, Traykovski P. Constraining denitrification in permeable wave-influenced marine sediment using linked hydrodynamic and biogeochemical modeling. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2008;275:127–137. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boano F, Demaria A, Revelli R, Ridolfi L. Biogeochemical zonation due to intrameander hyporheic flow. Water Resour Res. 2010;46:W02511. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zarnetske JP, Haggerty R, Wondzell SM, Bokil VA, González-Pinzón R. Coupled transport and reaction kinetics control the nitrate sources-sink function of hyporheic zones. Water Resour Res. 2012;48:W11508. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbott BW, et al. Using multi-tracer inference to move beyond single-catchment ecohydrology. Earth Sci Rev. 2016;160:19–42. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marzadri A, Tonina D, Bellin A. Morphodynamic controls on redox conditions and on nitrogen dynamics within the hyporheic zone: Application to gravel bed rivers with alternate-bar morphology. J Geophys Res. 2012;117:G00N10. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marzadri A, Tonina D, Bellin A, Tank JL. A hydrologic model demonstrates nitrous oxide emissions depend on streambed morphology. Geophys Res Lett. 2014;41:5484–5491. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reisinger AJ, Tank JL, Rosi-Marshall EJ, Hall RO, Baker MA. The varying role of water column nutrient uptake along river continua in contrasting landscapes. Biogeochemistry. 2015;125:115–131. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomez-Velez JD, Harvey JW, Cardenas MB, Kiel B. Denitrification in the Mississippi river network controlled by flow through river bedforms. Nat Geosci. 2015;8:941–945. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulholland PJ, et al. Stream denitrification and total nitrate uptake rates measured using a field 15N tracer addition approach. Limnol Oceanogr. 2004;49:809–820. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu T, Xia X, Liu S, Mou X, Qiu Y. Acceleration of denitrification in turbid rivers due to denitrification occurring on suspended sediment in oxic waters. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:4053–4061. doi: 10.1021/es304504m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leopold LB, Maddock T. The Hydraulic Geometry of Stream Channels and Some Physiographic Implications. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1953. Tech Rep 57. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhoads BL. A continuously varying parameter model of downstream hydraulic geometry. Water Resour Res. 1991;27:1865–1872. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raymond PA, et al. Scaling the gas transfer velocity and hydraulic geometry in streams and small rivers. Limnol Oceanogr Fluids Environ. 2012;2:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yalin MS. Geometrical properties of sand waves. Proc Amer Soc Civ Eng, J Hydraul Div. 1964;90:105–119. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikeda S. Prediction of alternate bar wavelenght and height. J Hydraul Eng. 1984;110:371–386. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buffington JM, Montgomery DR, Greenberg HM. Basin-scale availability of salmonid spawning gravel as influenced by channel type and hydraulic roughness in mountain catchments. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2004;61:2085–2096. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGuire KJ, et al. Network analysis reveals multiscale controls on streamwater chemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:7030–7035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404820111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goode JR, et al. Potential effects of climate change on streambed scour and risks to salmonid survival in snow-dominated mountain basins. Hydrol Process. 2013;27:750–765. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rutherford JC. River Mixing. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jobson AE, Sayre WW. Vertical transfer in open channel flow. J Hydraul Div. 1970;96:703–724. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salarashayeri AF, Siosemarde M. Prediction of soil hydraulic conductivity from particle-size distribution. World Acad Sci Eng Technol. 2012;61:454–458. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elliott AH, Brooks NH. Transfer of nonsorbing solutes to a streambed with bed forms: Theory. Water Resour Res. 1997;33:123–136. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen HV, Fehlman HM, Mendoza C. Bed form resistances in open channel flows. J Hydraul Div. 1990;116:799–815. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jähne B, et al. On the parameters influencing air-water gas exchange. J Geophys Res. 1987;92:1937–1949. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wanninkhof R. Relation between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean. J Geophys Res. 1992;97:7373–7382. [Google Scholar]