Significance

Languages are an important part of our culturally diverse world, yet many of today’s languages are in danger of dying out. To save endangered languages, one must first understand the dynamics behind language shift: what are the driving factors of people giving up one language for another? Here, we model language dynamics in time and space starting from empirical data. We show that it is the interaction with speakers of the same language that fundamentally determines spread and retreat of a language. This means that a minimum-sized neighborhood of speakers interacting with each other is essential to preserve the language.

Keywords: language shift, diffusion, language dynamics, quantitative linguistics, cellular automata

Abstract

Many of the world’s around 6,000 languages are in danger of disappearing as people give up use of a minority language in favor of the majority language in a process called language shift. Language shift can be monitored on a large scale through the use of mathematical models by way of differential equations, for example, reaction–diffusion equations. Here, we use a different approach: we propose a model for language dynamics based on the principles of cellular automata/agent-based modeling and combine it with very detailed empirical data. Our model makes it possible to follow language dynamics over space and time, whereas existing models based on differential equations average over space and consequently provide no information on local changes in language use. Additionally, cellular automata models can be used even in cases where models based on differential equations are not applicable, for example, in situations where one language has become dispersed and retreated to language islands. Using data from a bilingual region in Austria, we show that the most important factor in determining the spread and retreat of a language is the interaction with speakers of the same language. External factors like bilingual schools or parish language have only a minor influence.

It is estimated that around 90% of the world’s 6,000 languages will be replaced by a few dominant languages by the end of the 21st century (1). This replacement, which is called “language shift” (2), leads to a loss of cultural diversity. To prevent this loss and preserve endangered languages, researchers have been trying to find and quantify the factors behind language shift. Language shift (speakers giving up use of one language in favor of another) is driven by a variety of influences, for instance, demographic and social factors (3–5). To quantify the influence of each of these factors and to study language shift on a large scale, mathematical models and computer simulations have been proposed (6, 7). These models generally fall into two categories: (i) macroscopic reaction–diffusion equations that describe the concentration (fraction) of speakers in the population; (ii) microscopic agent-based models that simulate the actions of individual speakers (“agents”) changing their language with a certain probability at each interaction. For evaluating both types of model, parameters are required that can be empirically measured so that they can be fitted to data (8). This means that data covering language use over time and space are needed, but such data are often not available in sufficient resolution. Therefore, mathematical models have so far only rarely been checked against data on actual language use.

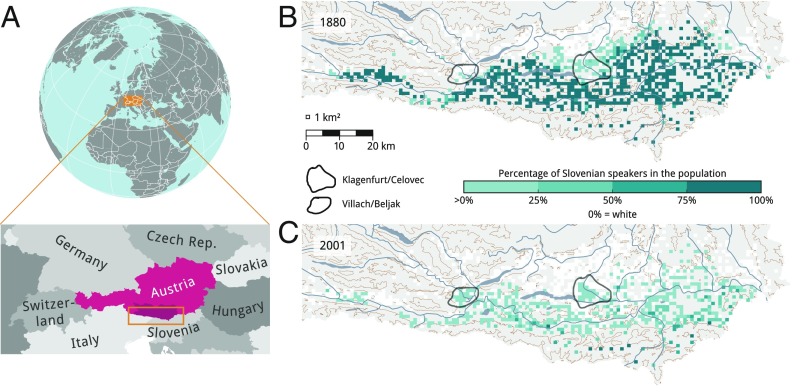

In this work, we combine mathematical modeling with very detailed empirical data. Applying diffusion theory from physics, we propose a simple model to describe the dynamics of language shift on a microscopic scale based on the principles of cellular automata/agent-based modeling (9, 10). The historical data come from southern Carinthia, Austria, which provides an extremely well-documented linguistic ecosystem with the interaction of two languages on one and the same territory. Carinthia was a federal state of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918 and of the Federal Republic of Austria afterward. It is geographically separated by a high mountain range, the Karawanks, from the neighbor country Slovenia where Slovenian is the national language. In southern Carinthia, which comprises the districts Klagenfurt and Völkermarkt and parts of the districts Hermagor and Villach (Fig. 1A), the population spoke and speaks partly German and partly Slovenian, the territories being intermixed (11). However, the number of Slovenian speakers in Carinthia has drastically decreased between 1880 and 2001 (Fig. 1 B and C), and language shift is taking place. We use the data from this case to evaluate our proposed model and its assumptions. Checking against empirical data also allows us to explicitly identify the factors influencing language shift and quantify their impact.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of Slovenian speakers in southern Carinthia according to census results. (A) Geographic location of southern Carinthia. The study area is indicated by the orange rectangle in the map at Bottom Left. (B) Census results for 1880. (C) Census results for 2001. Cells without any Slovenian speakers (0%) are shown in white. Each square marks a 1 × 1-km cell. Contour lines are in brown, and rivers and lakes are in gray. The two biggest Carinthian towns, Villach and the capital Klagenfurt, are encircled according to present administration.

Limits of the Classic Macroscopic Reaction–Diffusion Approach

In the past, language spread and retreat were mostly investigated on a macroscale using differential equations. Macroscopic approaches gained popularity after Abrams and Strogatz (12) published a short seminal paper in 2003 describing the retreat of languages with what they called lower status by differential equations. Their differential equation system considered only temporal and no spatial development, but the paper has drawn a tail of publications in its wake, many of them including spatial development. Spatial and temporal development of languages are usually combined in reaction–diffusion equations (13–19) of the form ∂u/∂t = D·∂2u/∂x2 + f(u). These types of equation are also used in other fields, for example, biology or chemistry, to describe all kinds of spread phenomena (20).

Considering a language with higher status, for example, German vs. Slovenian in Carinthia, the development of the fraction uG(x,t) of German speakers in the total population can be written as a reaction–diffusion equation following Fisher’s equation for advantageous genes (21):

| [1] |

Here, DG is the diffusivity of German language and k is the conversion rate from Slovenian to German. The fraction of Slovenian speakers is given by uS = 1 − uG.

In Carinthia, the language front between German and Slovenian essentially advances only southward motivating a one-dimensional treatment. Eq. 1 then results in a traveling front of the higher status language (in this case German) with velocity v:

| [2] |

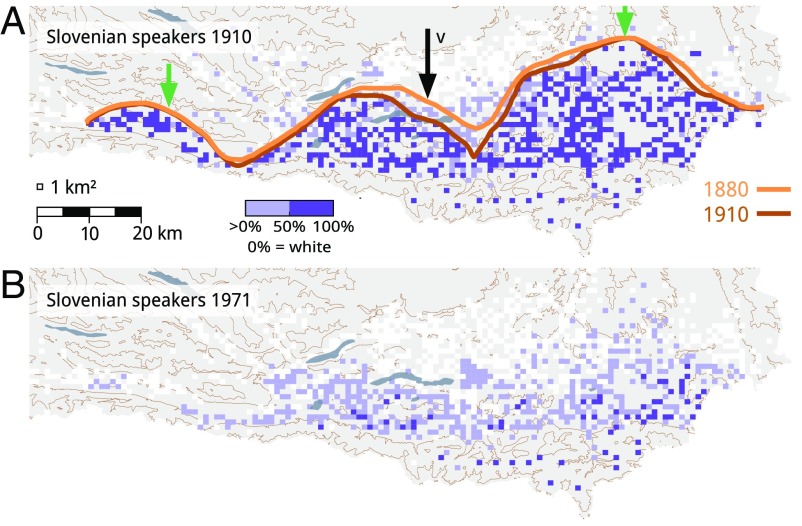

We defined the front as the line bordering all cells with more than 50% Slovenian speakers each without including outlier cells detached from the contiguous language area (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Slovenian language area in southern Carinthia for two different periods. (A) Percentage of Slovenian speakers in 1910. Schematic of language front movement between 1880 (orange line) and 1910 (brown line). The language front is shown as the line bordering the cells with more than 50% Slovenian speakers each. Black arrow, direction of front movement. Green arrows, areas behind mountain ranges without front movement. (B) Percentage of Slovenian speakers in 1971. No continuous language front can be defined.

From the data, the velocity of the language front can be derived (Table S1) and the product of diffusivity and conversion rate DG·k can be determined (Supporting Information). If data on the conversion rate are available, the diffusivity of the majority language can be estimated.

Table S1.

Comparison of the language front velocity v for the period 1880–1910

| Language front velocity v | Value |

| From census data* | |

| v | 0.034 ± 0.017 km/y |

| Calculated† | |

| DG (fitted to the whole period) | 0.1356 ± 0.0050 km2/y |

| k | 0.0224 ± 0.0065/y |

| v | 0.1101 ± 0.0034 km/y |

Obtained directly from census data (Eq. S1).

Calculated as , which results from the reaction–diffusion equation. For this calculation, we use the fit parameter DG of the microscopic model and k from census data.

In the period 1971–2001, no contiguous language area exists due to the large decrease in the number of Slovenian speakers (Fig. 2B). The cells with significant fractions of minority language have become dispersed and the minority language has retreated to language islands. Hence there is no continuous language front that clearly separates the two language areas of Slovenian and German. From this, it is evident that the concept of a language front fails when the minority language no longer covers a contiguous area, and reaction–diffusion equations and the resulting language front are not applicable in this case.

Noting the limits of treatment by reaction–diffusion equations, we take a different approach. We simulate the microdevelopment on the basis of the smallest registered population units, hence providing a spatially much more detailed description of language spread and retreat than the macroscale description by reaction–diffusion equations. As a result, we can follow not only global development over time and space but also local processes such as the deviating dynamics in urban areas.

Materials and Methods

We start by taking the data of the censuses in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire that were held in 10-y intervals beginning from 1880 until 1910. Such censuses were continued in the Federal Republic of Austria from 1971 until 2001. In between, the two world wars and the after-war turbulences prevented consistent censuses and data with the same level of detail is not available. In the censuses together with several other items, the vernacular language of each person was asked for and registered. In the censuses until 1910, only one language could be recorded in the questionnaire, whereas in the censuses after 1971 also bilingualism could be indicated. For the sake of simplicity and consistency and data with the same level of detail is not available, we included bilingual Slovenian–German speakers in the minority group, that is, Slovenian speakers. In this paper, we do not consider bilingualism as a separate speaker state. We neither consider the different Slovenian and German dialects that are not encoded in the census data. From the census results, we read the number of German and Slovenian speakers in each of the ∼1,500 population units (hamlets, villages, and towns) in southern Carinthia.

Mapping the Data.

For our study of language dynamics in Carinthia, the area investigated is subdivided into a quadratic grid with cells sized 1 × 1 km. Carinthia spans ∼2.4° of longitude or 184 km (east border to west border) and 0.8° of latitude or 84 km (north border to south border). We thus cover the total area of Carinthia with a regular grid of 84 × 184 = 15,456 cells of 1 × 1 km each. Of these 15,456 cells, 9,549 comprise the actual area of Carinthia. A total of 1,170 of the cells inside the Carinthian borders is populated by data for speakers in southern Carinthia. Data for the number of speakers was extracted from census records for the period from 1880 to 1910 (22–25) and the raw dataset for 1971–2001 (special evaluation commissioned from Statistics Austria). Digitized data can be accessed on figshare (https://figshare.com/articles/Language_use_in_Carinthia/4535399). Speaker data are assigned to cells based on the geographic coordinates of the population unit. Geographic coordinates (WGS 84) were obtained from KAGIS Kärnten Atlas (https://gis.ktn.gv.at/). The 10-y periods between the censuses are divided into 1-y time steps for the simulation.

Language Shift Model.

As a first basic model, we assume that in each cell after 1 y’s time the probability pα(r, t + 1) to speak a language α will be proportional to the local number of speakers of that language in the preceding year nα(r, t) plus an increase through interaction Fα(r, t) with speakers of the same language in the neighborhood cells. pα(r, t + 1) is normalized to the total number of speakers and the total interaction in that cell. We obtain Eq. 3 for the probability pα(r, t + 1) to speak language α (where α = G or S, German or Slovenian) in the cell located at position r at time t + 1

| [3] |

To calculate pα for the first year of the simulation, Fα and nα are calculated from the initial census data. Afterward, Fα and nα are calculated for each year from the result of the preceding year as follows.

The number of speakers of a language α at position r at time t, nα(r, t), is given by Eq. 4: the probability pα(r, t) to speak the language α at time t multiplied by the total number of people in the cell ntotal(r, t), which for each time step and cell is given by linear interpolation between censuses:

| [4] |

Each interaction term Fα(r, t) is a sum over the contributions of all other cells surrounding the initial cell at position r. The interaction Fα with speakers of the same language α in the neighboring cells at rj is as follows:

| [5] |

The contributions cα(r, rj, nα, t) of all other cells positioned at rj surrounding the initial cell at position r are modeled by Gaussian functions identical to distributions describing the diffusion of particles in physics or chemistry:

| [6] |

where Dα are the diffusivities of each language, that is, measures for their spread. The diffusivities can also be seen as a measure for the region of influence of a language. We set Δt = 1 y because cα is calculated individually for each year from the result of the preceding year.

The Gaussian function is a simple choice to model the interaction with neighboring cells and provides a good fit with the census data. In an extension of our model, this interaction could be modeled by other functions such as leptokurtic (long-tail) distributions or combinations of functions to describe more complex interaction patterns, for example, both long-range and short-range interaction.

Evaluation Procedure.

Simulations were performed using GNU Octave 4.0.0. The data from the first census in each period (1880 and 1971) were set as the initial state from which the number of speakers in each cell changes according to Eqs. 3 and 4, assuming a linear population development between censuses. To evaluate the goodness of fit between simulated data and census data, we use ordinary least squares (OLS) to minimize the squared sum of errors:

| [7] |

where Oi is an observed data point (census data) and Ei is an estimated data point (simulated data). t is the number of times the observed data can be compared with the estimated data. t runs from 1 to m − 1, where m is the number of censuses within the period. The data from the first census in each period are excluded as they are equivalent to the initial state of the system; hence there is no error for the initial state and we sum only over the remaining censuses. Optimization was done using the Nelder–Mead method (26). Additionally, we used least absolute errors (LAE) as follows:

| [8] |

that is, minimizing the sum of the absolute errors to check the reliability of the fit. General model performance is evaluated by comparison with a baseline. Comparison values can be found in Table S2.

Table S2.

Comparison of the goodness of fit for the baseline model, the interaction model and the interaction model with habitat parameter

| Period | ||||||

| 1880–1910 | 1971–2001 | |||||

| Model | Total no. of Slovenian speakers in 1910 | RMSE per 30 y (speakers) | MAE per 30 y (speakers) | Total no. of Slovenian speakers in 2001 | RMSE per 30 y (speakers) | MAE per 30 y (speakers) |

| Baseline model | 85,233 | 52.41 | 20.32 | 16,336 | 17.86 | 9.35 |

| Interaction model | 67,727 | 44.11 | 18.41 | 11,260 | 15.06 | 8.01 |

| Interaction model with habitat | 64,092 | 41.75 | 18.41 | 12,052 | 12.94 | 6.93 |

| Census data | 65,352 | — | — | 12,056 | — | — |

Comparison values for the goodness of fit of the baseline model (constant fraction of speakers of either language), the interaction model (Eq. 3), and the interaction model with habitat (Eq. 9). Three metrics are shown: the total number of Slovenian speakers (closer to the real number is better), the root-mean-square error (RMSE) (Eq. S4; lower is better) and the mean absolute error per cell (MAE) (Eq. S5; lower is better). All results given for best fits (Table 1 and Supporting Information). The model with habitat includes the bilingual schools habitat parameter for the period 1880–1910 and the urban habitat parameter for the period 1971–2001.

Results

Language Shift in the Period 1880–1910.

The widths of both Gaussians, and hence the diffusivities for German and Slovenian, are fitted to the number of speakers in each cell as given by the census data. Fits to the census data were performed for the period from 1880 to 1910. The best solution was achieved with the values given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Fit values for the diffusivities Dα for both time periods

| Period | ||

| Diffusivity | 1880–1910 | 1971–2001 |

| DG, km2/y | 0.1356 | 0.1078 |

| DS, km2/y | 0.0939 | 0.0926 |

Diffusivities Dα according to simulations for both periods. Changing both diffusivities in the same direction and by the same amount changes little in the quality of the fit, whereas even a small change to the ratio of diffusivities has a big impact on fit quality. A 10% change of both diffusivities in the same direction leads to a 1% change in the sum of absolute errors. On the other hand, if only one diffusivity is changed by 10% (i.e., the ratio between diffusivities changes as well), this leads to a 10% change in the sum of absolute errors.

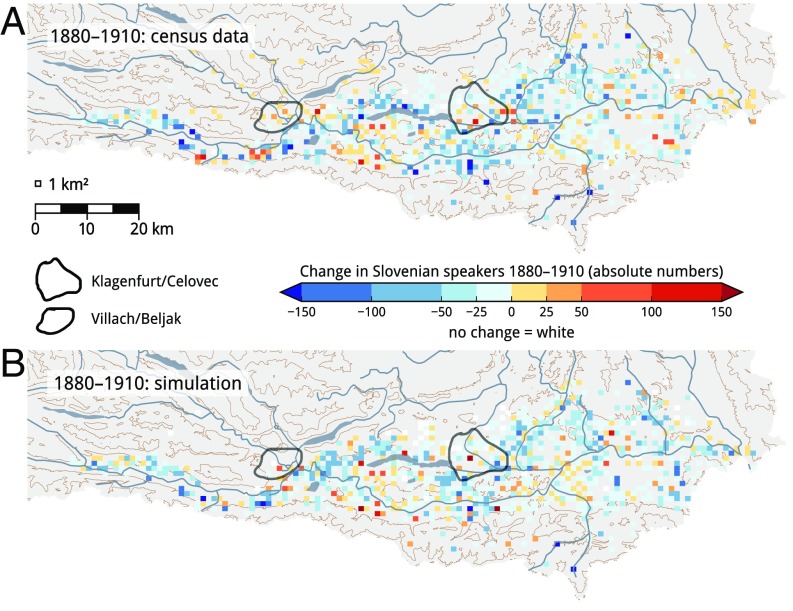

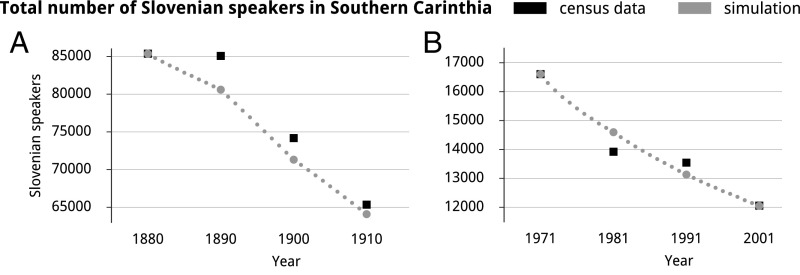

Fig. 3 shows the increase (red) and decrease (blue) of the number of Slovenian speakers in southern Carinthia for census data and simulated data. We obtain satisfactory agreement between the empirical data and the predicted data on a microscopic scale. In detail, this can be seen in Fig. S1 where the model's errors are shown for cells with different numbers of Slovenian speakers. The total number of Slovenian speakers as predicted by the simulation also agrees with the census data (Fig. S2). Fig. S3 shows the residuals (census data minus simulated data). Thus, our model is able to follow how either language has spread and retreated in the time period 1880–1910.

Fig. 3.

Increase and decrease in the number of Slovenian speakers in southern Carinthia between 1880 and 1910. (A) Census data. (B) Optimum simulation without habitat parameters. Increase is shown in shades of red, and decrease, in shades of blue. Numbers shown are absolute numbers. The optimum simulation with the bilingual schools habitat parameter (Supporting Information) is not shown because there is no visible difference compared with B.

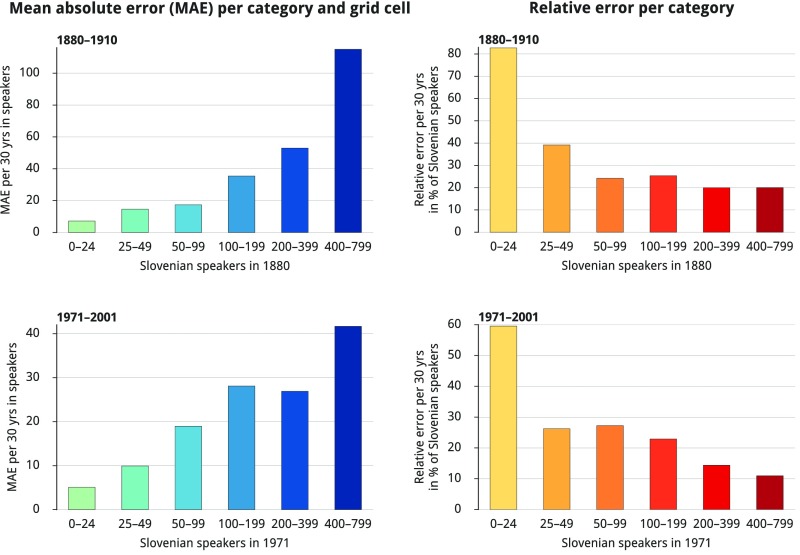

Fig. S1.

Measures of the model’s reliability compared with census data: mean absolute error per category in speakers (Left) and relative error per category in percentage of speakers (Right). Both errors shown are per 30 y. Categories are set by the number of Slovenian speakers in the initial state of the system (census data from 1880 and 1971, respectively). The simulated data for the period from 1880 and 1910 is calculated including the habitat parameter for bilingual schools; the data for the period from 1971 to 2001 is calculated including the habitat parameter for urban areas (Supporting Information).

Fig. S2.

Total number of Slovenian speakers in southern Carinthia as estimated by the simulation (gray dots) and according to census data (black squares). (A) Period from 1880 to 1910. (B) Period from 1971 to 2001. The simulated data for the period from 1880 and 1910 are calculated including the habitat parameter for bilingual schools; the data for the period from 1971 to 2001 are calculated including the habitat parameter for urban areas (Supporting Information).

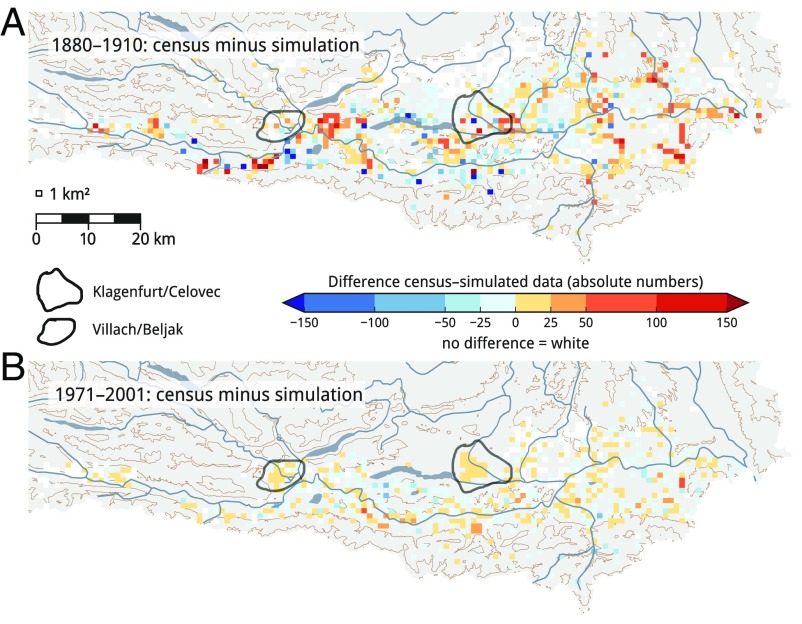

Fig. S3.

Residuals: census data for the last year of each period minus simulated result at the end of each period. (A) Period from 1880 to 1910. (B) Period from 1971 to 2001. As in Fig. S2, the simulated data for the period from 1880 and 1910 are calculated including the habitat parameter for bilingual schools; the data for the period from 1971 to 2001 are calculated including the habitat parameter for urban areas (Supporting Information).

Extension of the Model Through Habitat Parameters.

In a second step, for the period from 1880 to 1910, the influence of habitat conditions, such as the influence of urban areas, that is, major towns, the language of schools, and language in parishes, was investigated. To this end, we introduced a habitat parameter hi into Eq. 3, which modifies the effect of local speakers by an exponential function with the argument (±Hhi). The multiplicative factor H indicates the presence (H = 1) or absence (H = 0) of a local habitat condition, that is, H = 1 for the two largest towns Klagenfurt and Villach or if a bilingual school or Slovenian parish existed. Otherwise, H is set to zero. The exponential function was chosen as a modifier because it is a simple function, which for small hi adds nhi to the speaker effect if H = 1, while recovering the basic model (Eq. 3) if H = 0. We obtain the following equation for the probability pα(r, t + 1) of speaking a language α at position r and time t + 1:

| [9] |

Optimization was performed as before. Of the three investigated parameters (urban areas, bilingual schools, and parish language), only that of bilingual schools showed a small influence (Supporting Information). However, the influence is so small that Fig. 3B does not visibly change with the introduction of the bilingual-schools habitat parameter.

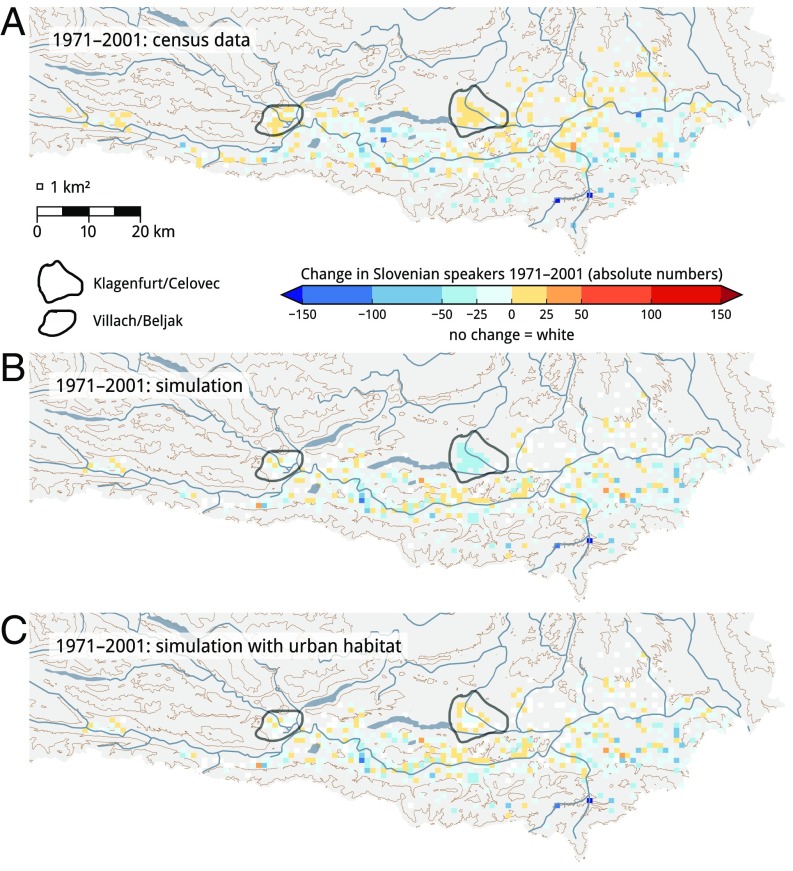

Language Shift in the Period 1971–2001.

After simulating the language dynamics during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, we now turn to language development in the second period after the two world wars. The development from 1971 to 2001 was first pursued using the same basic model (Eqs. 3 and 4). Table 1 shows the numerical results and Fig. 4 A and B shows the increase (red) and decrease (blue) of the number of Slovenian speakers in southern Carinthia for census data and simulation. We also investigated the influence of two habitat parameters for this period: urban areas and parish language. Only the urban habitat parameter resulted in a noticeable difference in goodness of fit (Fig. 4C and Supporting Information). Errors depending on the number of Slovenian speakers present are shown as before in Fig. S1.

Fig. 4.

Increase and decrease in the number of Slovenian speakers in southern Carinthia between 1971 and 2001. (A) Census data. (B) Optimum simulation without habitat parameters. (C) Optimum simulation with urban habitat parameter. Increase is shown in shades of red, and decrease, in shades of blue. Numbers shown are absolute numbers. In B, no additional habitat parameter was introduced, and a difference between census data and simulation in the two urban centers Klagenfurt and Villach is particularly visible in this period. This difference indicates a deviating development in urban areas, which requires the introduction of an additional habitat parameter (Supporting Information).

Local Differences in the Language Diffusivities.

We have cut out three regions in the districts of Völkermarkt, Klagenfurt, and Villach to search for local differences in the diffusion behavior: is there a difference between rural and urban regions?

In all three regions in the districts of Völkermarkt, Klagenfurt, and Villach, the diffusivity of the Slovenian language DS is between 25 and 50% lower than the diffusivity of the German language DG, with the largest difference (factor of 2) for the urban region of Klagenfurt. We suppose that the discrepancies between the different regions are due to local differences in language spread and retreat because of differences in geography and population distribution: faster diffusion in urban areas, German diffusing particularly faster than Slovenian in urban region of Klagenfurt.

Conclusion and Discussion

Macroscopic vs. Microscopic Models.

In the past, language dynamics have been commonly described on a macroscopic scale by reaction–diffusion equations that model the fraction of speakers of a language in the population. However, this treatment breaks down when the spread of one language and the retreat of the other one no longer follows a traveling front because one language has become dispersed and has retreated to language islands (Fig. 2B). Additionally, reaction–diffusion equations are not applicable at all in areas without any language front movement such as behind mountain chains (green arrows in Fig. 2A). In contrast, the development can still be followed and predicted in both cases with our microscopic model. The microscopic model also takes into account the interaction with all neighboring cells, whereas in the case of a macroscopic language front the interaction only comes from one direction. Thus, microscopic models yield a more detailed and complete description of language spread and retreat than macroscopic treatment by reaction–diffusion equations.

A challenge for microscopic models on a realistic basis is obviously the need for empirical detailed data (as were at hand for this work) from which to determine the diffusivities. For this reason, language censuses have to be conducted in regular intervals and with fine-grained spatial resolution.

What Drives Language Shift?

We have shown that the data predicted by our basic model (Eqs. 3 and 4) show satisfactory agreement with the historical data for the period between 1880 and 1910. Even in different socioeconomic conditions (the second period between 1971 and 2001), the predicted data still match the empirical data. This means that the basic model can reliably reproduce language dynamics of the studied language competition between Slovenian and German.

The model is also able to reveal similarities between physical phenomena like atomic diffusion and social phenomena like language shift: by modeling linguistic interaction as a Gaussian function as in models of physical diffusion, we obtain good agreement between the predicted and the empirical data. Thus, we have illustrated that it is possible to use physical models to simulate social dynamics on a large scale over time and space.

The basic model uses only two parameters to calculate the probability of speaking a language: the number of speakers in the preceding year and interaction between speakers. Both of these can be directly calculated from census data, ensuring our model is applicable even in situations where data on other factors influencing language use (e.g., perceived status of a language) is not available or even possible to obtain. Without interaction (i.e., using only the number of speakers), the probability of speaking a language (Eq. 3) remains constant. Consequently, interaction with other speakers is an essential drive for the linguistic change in each cell. This point has been argued by linguists (27) and is validated by our simulation. The number of speakers of a language in the population units (hamlets, villages, towns) neighboring the given cell is therefore an important influence on language dynamics. This means that a minimum-sized neighborhood of speakers of the minority language interacting with each other is necessary to preserve the language.

In addition, the simulation shows that other habitat conditions (the language of schools, and in parishes) are of minor influence. There is, however, a noticeable effect of urban areas, which have their own dynamics: between 1880 and 1910, Slovenian decays slightly faster in the larger towns than predicted by the basic model; between 1971 and 2001, the development is reversed, that is, the number of Slovenian speakers increases at a higher rate in large towns than predicted by the basic model (Supporting Information). This reverse in development might be attributed to language playing a larger role in people’s identity in an increasingly mobile society (after 1971) compared with a largely rural society (as between 1880 and 1910). When language makes up a larger part of one’s identity, there might be a higher tendency to preserve or revive it. This preservation happens, for example, through language associations and cultural clubs, which commonly originate in large towns and consequently have their largest impact there (3). With our model, it is possible to follow these different local developments and quantify the strength of their influence.

As interaction is the driving force for linguistic change in our model, it also offers a tool for possible future work on how interaction shapes language use: what happens when the interaction with speakers of the same language is considerably higher than the interaction with speakers of a different language? How much interaction with the same language (vs. interaction with a different language) is needed for the preservation of the minority language?

Language Front Velocity

To measure front velocity per year for the period 1880 (t1) to 1910 (t2) directly from the census data (Fig. 2A), we horizontally divide the language front into n points. For each point Pi of the language front, we then determine the north–south difference between its two positions Pi(t1) and Pi(t2). The difference between points is divided by the number of years between 1880 and 1910:

| [S1] |

This measured velocity can then be compared with the velocity of the traveling front (Eq. 2) resulting from the reaction–diffusion equation (Eq. 1). For calculating the velocity from Eq. 2, we use the diffusivity DG deduced from the fits (Table 1) and the language conversion rate k derived from the original census data.

To obtain the language conversion rate k, we use census data from 1880 (t1) and 1910 (t2) and calculate the fraction uG of German speakers in the population. For pure growth (diffusion term in Eq. 1 neglected) and dividing by the number of years between 1880 and 1910, k becomes the following:

| [S2] |

where is the average between uG(t1) and uG(t2). In 1880, there were 102,314 German and 85,369 Slovenian speakers in southern Carinthia. In 1910, there were 154,361 German and 65,352 Slovenian speakers in southern Carinthia. Assuming the error in census data to be 10%, we obtain k = 0.0224 ± 0.0065/y.

Results are given in Table S1. We see that the velocity calculated from the reaction–diffusion equation (Eq. 2) is considerably higher than the velocity derived from the census data. This is due to the fact that the velocity derived from census data averages over the whole area. However, there is no movement of the language front where the minority region borders unpopulated areas as is the case in large parts of the minority region (Fig. 2A), whereas reaction–diffusion equations assume that there is a moving language front everywhere. This shows an important limitation of treatment by reaction–diffusion equations: reaction–diffusion equations are not applicable in the absence of “pressure” from a region consisting mainly of speakers of the majority language, which leads to front movement.

Extension of the Model Through Habitat Parameters

To describe external influences such as larger towns, schools, or parishes, we introduced a habitat parameter hi into Eq. 3 (see Eq. 9), which modifies the effect of local speakers as follows:

| [S3] |

We assume that the effect is symmetrical, that is, if the effect on Slovenian speakers is given by , then the effect on German speakers is given by . In the presence of an external influence i, H is set to 1 and the coefficient hi gives the strength of influence. In cells without an external influence, H = 0 and Eq. 3 is recovered. The exponential function was chosen as a modifier because it is a simple function that for small hi adds nhi to the speaker effect if H = 1, while recovering the basic model (Eq. 3) if H = 0.

Urban Centers

Language change patterns differ depending on whether the environment is rural or urban. Fishman (28) argues that speakers in an urban area are typically more likely to shift from the minority to the majority language, whereas the inhabitants of isolated rural areas resist language shift. Movement to larger urban agglomerations therefore increases the risk of giving up the minority language in favor of the majority language.

This development is marginally noticeable in the period from 1880 to 1910 for the two largest towns Klagenfurt and Villach. In these two towns, the number of Slovenian speakers decreases slightly faster than the basic model (Eqs. 3 and 4) predicts. An interesting phenomenon appears between 1971 and 2001 when loss of minority language by moving to urban centers is reversed: the number of Slovenian speakers now definitely increases faster in urban centers than predicted by the basic model. These localized developments can be captured by our model by introducing a parameter h1 and setting H = 1 in the largest towns for each period (Klagenfurt and Villach).

Best fit for the period from 1971 to 2001 is provided by h1 = 0.025 ± 0.005. h1 is positive for this period, which means that Slovenian speakers have more impact (Eq. S3). The model with this urban habitat parameter better describes the actual data in these urban centers in the sense that it better reproduces the direction of change, that is, decrease or increase.

The difference in Fig. 4C between the outskirts and inner cells of the city of Klagenfurt is a result of the model dynamics: The outer cells have populated neighbor cells only on one side whereas the inner cells are completely surrounded by populated cells. Introducing a habitat condition h increases the probability of speaking Slovenian in the outer cells compared to the model without habitat. On the contrary, in the inner cells the effect of h is compensated by interaction (F) with German speakers in the neighboring cells and the increase in Slovenian speakers is not as strong. This color difference would vanish for larger values of h.

Bilingual Schools

Between 1880 and 1910, so-called utraquistic elementary schools were meant to teach pupils in both languages (29). In 1880, these schools existed in 83 population units (villages and towns) in the bilingual region of southern Carinthia (30). We examined whether in these villages and towns (H = 1) the Slovenian language was preferentially preserved compared with localities where no such school existed.

Best fit for the period between 1880 and 1910 was achieved with h2 = −0.0224 ± 0.0050. From Eq. S3, it follows that the presence of an utraquistic school decreases the impact of existing Slovenian speakers.

After World War II the bilingual instruction system in the elementary schools was repeatedly changed and unfortunately no detailed data are available on how many pupils attended classes in Slovenian language.

Parishes

In villages with a Slovenian majority from 1880 to 1910, mostly Slovenian native-language speakers were hired as priests (31). They read the mass in Slovenian language. Altogether, there were 98 Slovenian-language parishes in the bilingual region in southern Carinthia in 1880 (32). We examined the influence of these parishes on the development of Slovenian by applying the same procedure as for the schools: H = 1 in villages or towns with masses in Slovenian, else H = 0. Neither in the first nor in the second period we could find a substantial influence of Slovenian-language parishes on the probability of speaking Slovenian.

Evaluating Model Performance

To evaluate model performance, a baseline for comparison is helpful. As a baseline, we use an interaction free model (Fα = 0), which means that the fraction of speakers of either language remains constant, speakers being lost or gained only through changing population size. To check if our model is better than the baseline, we use three metrics:

-

i)

The total number of Slovenian speakers in the last year of each period as calculated by the model, which should be close to the real number.

-

ii)

Root-mean-square error (RMSE), which is related to OLS (Eq. 7). The RMSE gives the mean error per cell per 30 y in speakers, which should be low:

| [S4] |

where Oi is an observed data point (census data), Ei is an estimated data point (simulated data), and n is the number of populated cells.

-

iii)

Mean absolute error (MAE), which is related to LAE (Eq. 8). The MAE is the sum of absolute errors divided by the number of cells n, which should also be low:

| [S5] |

For both errors, the result of the simulation after 30 y is compared with the census data at the end of each 30-y period. Results are given in Table S2, indicating that the model with interaction (and optionally with habitat parameters) consistently leads to a better fit than the baseline. Note that RMSE and MAE average over all cells. A more detailed look into the model’s error per category/number of speakers in a cell is given below.

Reliability of the Model per Category

Fig. S1 shows two measures of the model’s reliability: the MAE (Eq. S5) per category and grid cell and the relative error per category. To gain insight into where the model works best, we show the error per category to differentiate between cells with different numbers of Slovenian speakers. Both errors are given per 30 y, that is, the error in the result of the simulation after 30 y compared with the census data at the end of each 30-y period.

The relative error is given by the sum of absolute errors divided by the sum of the number of Slovenian speakers in this category:

| [S6] |

where Si is the number of Slovenian speakers per grid cell, summed over the n grid cells in this category.

Total Sum of Slovenian Speakers

Fig. S2 shows the total sum of speakers of either language according to all eight censuses in both periods (1880, 1890, 1900, 1910, and 1971, 1981, 1991, 2001) in comparison with the simulated data. The agreement is satisfactory.

Deviation of Simulated Data from Census Data over Space

Fig. S3 shows the residuals for the two periods (census data minus simulated data). Evident deviations in period 1 find their explanation in extraordinary outliers in the census data: some villages switched from a strong German-speaking majority to a strong Slovenian-speaking majority. The same also happened in the opposite direction. Both of these developments are very different from the average trend in southern Carinthia, which was a moderate transformation from Slovenian speaking to German speaking. In addition, several villages “flip-flopped” from one census to the next, changing from a German-speaking majority to a Slovenian-speaking majority and then back to a German-speaking majority and back again to a Slovenian-speaking majority in the last census of the period. This behavior, which seemed to be influenced by local politics rather than actual language use changes, cannot be captured by our model. The residuals thus show where language spread and retreat deviates from “average” development and open up possibilities for further research: what were the reasons for these deviations? Can these reasons—which might be identified only by sociologically focused research—be integrated into the model as a habitat factor?

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Gehart and W. Zöllner as well as A. Bauer (Statistics Austria) and P. Ibounig (Department of Statistics, Government of the State of Carinthia) for providing census data. We also thank the Klagenfurt University Library and the Archive of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Gurk-Klagenfurt for access to data about bilingual schools and parish language. Discussions with M. Glauninger (Department of German Studies, University of Vienna/Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities, Austrian Academy of Sciences) are gratefully acknowledged. We thank C. Dellago for critical comments on the manuscript. The geographical data (shapefiles) used for the figure backgrounds and contour lines are provided by Land Kärnten (https://www.data.gv.at/auftritte/?organisation=land-kaernten) under a CC-BY-3.0 license. Diverging color scale is based on www.ColorBrewer.org. K.P. is supported by a uni:docs fellowship from the University of Vienna.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The digitized census data on language use for southern Carinthia, 1880–1910, from the Austrian/Austro-Hungarian census reported in this paper have been deposited in figshare (https://figshare.com/articles/Language_use_in_Carinthia/4535399).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617252114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages 2003 Language Vitality and Endangerment. Available at unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001836/183699E.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- 2.Weinreich U. Languages in Contact. Linguistic Circle of New York; New York: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsunoda T. Language Endangerment and Language Revitalization. An Introduction. Mouton; Berlin: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amano T, et al. Global distribution and drivers of language extinction risk. Proc Biol Sci. 2014;281(1793):20141574. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nettle D. Explaining global patterns of language diversity. J Anthropol Archaeol. 1998;17:354–374. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulze C, Stauffer D, Wichmann S. Birth, survival and death of languages by Monte Carlo simulation. Commun Comput Phys. 2008;3:271–294. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandler A. Demography and language competition. Hum Biol. 2009;81(2-3):181–210. doi: 10.3378/027.081.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang M, Gong T. Principles of parametric estimation in modeling language competition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(24):9698–9703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303108110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hegselmann R. Understanding social dynamics: The cellular automata approach. In: Troitzsch KG, Mueller U, Gilbert N, Doran JE, editors. Social Science Microsimulation. Springer; New York: 1996. pp. 282–306. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert N. Agent-Based Models. Sage; Los Angeles: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busch B. Slovenian in Carinthia—a sociolinguistic survey. In: Extra G, Gorter D, editors. The Other Languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic and Educational Perspectives. Multilingual Matters; Clevedon, UK: 2001. pp. 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrams DM, Strogatz SH. Linguistics: Modelling the dynamics of language death. Nature. 2003;424(6951):900. doi: 10.1038/424900a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patriarca M, Leppänen T. Modeling language competition. Physica A. 2004;338:296–299. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patriarca M, Heinsalu E. Influence of geography on language competition. Physica A. 2009;388:174–186. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandler A, Steele J. Ecological models of language competition. Biol Theory. 2008;3:164–173. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandler A, Unger R, Steele J. Language shift, bilingualism and the future of Britain’s Celtic languages. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365(1559):3855–3864. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walters CE. A reaction–diffusion model for competing languages. Meccanica. 2014;49:2189–2206. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fort J, Pérez-Losada J. Front speed of language replacement. Hum Biol. 2012;84(6):755–772. doi: 10.3378/027.084.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isern N, Fort J. Language extinction and linguistic fronts. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11(94):20140028. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray JD. Mathematical Biology I: An Introduction. Springer; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher RA. The wave of advance of advantageous genes. Ann Eugen. 1937;7:353–369. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Imperial-Royal Central Statistical Commission (1883) Special Orts-Repertorien der im Österreichischen Reichsrathe Vertretenen Königreiche und Länder. V. Kärnten [Special Village Registers of the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Austrian Imperial Council. V. Carinthia] (k.k. Staatsdruckerei, Vienna). German.

- 23. Imperial-Royal Central Statistical Commission (1894) Special Orts-Repertorien der im Österreichischen Reichsrathe Vertretenen Königreiche und Länder. Neubearbeitung auf Grund der Ergebnisse der Volkszählung vom 31. December 1890. V. Kärnten [Special Village Registers of the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Austrian Imperial Council. Revised Edition According to the Results of the Census of December 31, 1890. V. Carinthia] (k.k. Staatsdruckerei, Vienna). German.

- 24. Imperial-Royal Central Statistical Commission (1905) Gemeindelexikon der im Reichsrate vertretenen Königreiche und Länder, Bearbeitet auf Grund der Ergebnisse der Volkszählung vom 31. Dezember 1900. V. Kärnten [Municipality Reference Book of the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council, Revised According to the Results of the Census of December 31, 1900. V. Carinthia] (k.k. Staatsdruckerei, Vienna). German.

- 25. Central Statistical Commission (1918) Spezialortsrepertorium der Österreichischen Länder. Bearbeitet auf Grund der Ergebnisse der Volkszählung vom 31. Dezember 1910. V. Kärnten [Special Village Register of the Austrian Lands. Revised According to the Results of the Census of December 31, 1910. V. Carinthia] (Verlag der Staatsdruckerei, Vienna). German.

- 26.Nelder J, Mead R. A simplex-method for function minimization. Comput J. 1965;7:308–313. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieberson S. Forces affecting language spread: Some basic propositions. In: Cooper RL, editor. Language Spread: Studies in Diffusion and Social Change. Indiana Univ Press; Bloomington, IN: 1982. pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fishman J. The Sociology of Language. Newbury House; Rowley, MA: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurz M. 1990. Zur Lage der Slowenen in Kärnten. Der Streit um die Volksschule in Kärnten (1867–1914) [Concerning the Situation of Slovenes in Carinthia. The Dispute About Elementary Schools in Carinthia (1867–1914)] (Kärntner Landesarchiv, Klagenfurt, Austria). German.

- 30. Anonymous (1881) Lehrer-Kalender und Schematismus desSämmtlichenLehrpersonales der Volksschulen in Kärnten 1881 [Teachers’ Calendar and Schematism of the Complete Teaching Staff in Elementary Schools in Carinthia in 1881] (Bertschinger, Klagenfurt, Austria). German.

- 31.Veiter T. 1936. Die Slowenische Volksgruppe in Kärnten.Geschichte, Rechtslage, Problemstellung [The Slovenian Ethnic Group in Carinthia. History, Legal Status, Problems] (Reinhold-Verlag, Vienna). German.

- 32. Catholic Church Diocese Gurk (1880) Geistlicher Personalstand der Diözese Gurk im Jahre 1880 [List of Clerical Personnel in the Diocese Gurk in the Year 1880] (Verlag der St. Gurker Ordinariatskanzlei, Klagenfurt, Austria). German.