Abstract

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinico-radiological syndrome characterized by a headache, seizures, altered mental status and visual loss and characterized by white matter vasogenic edema affecting the posterior occipital and parietal lobes of the brain predominantly. This clinical syndrome is increasingly recognized due to improvement and availability of brain imaging specifically magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A 35-year-old female with the history of unsafe abortion and massive blood transfusion 10 days ago was brought to the emergency room with three episodes of generalized tonic–clonic seizures, urinary incontinence and altered sensorium since 3 hours. MRI brain showed bilateral occipital, parietal, frontal cortex and subcortical white matter T2/Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities, suggestive of PRES. The patient improved after management with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, antiepileptics and monitoring of blood pressure. If recognized and treated early, the clinical syndrome commonly resolves within a week. PRES can be a major problem in rapid and massive blood transfusion. A high index of suspicion and prompt treatment can reduce morbidity, mortality and pave the path for early recovery.

INTRODUCTION

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinico-radiological syndrome characterized by symptoms including a headache, seizures, altered consciousness and visual disturbances [1]. PRES was first described in 1996 by Hinchey et al. [2]. Shortly after the description in 1996, two other case-series were published [3]. This condition has been known by various names previously (reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, reversible posterior cerebral edema syndrome and reversible occipital parietal encephalopathy). PRES is now the widely accepted term [4]. It is commonly, but not always associated with acute hypertension [1]. This clinical syndrome is increasingly recognized, commonly because of improvement and availability of brain imaging.

The major clinical conditions associated with PRES are represented in Table 1. There is wide variation in the severity of clinical symptoms, i.e. the visual disturbance can vary from blurred vision, homonymous hemianopsia to cortical blindness. Altered consciousness may vary from mild confusion or agitation to coma. Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting and brainstem deficits. Seizures and status epilepticus are common, while non-convulsive status epilepticus may be common than generalized status epilepticus.

Table 1:

PRES-associated clinical conditions

| Preeclampsia |

| Eclampsia |

| Infection/Sepsis/Shock |

| Autoimmune disease |

| Cancer chemotherapy |

| Transplantation including bone marrow or stem cell transplantation |

| Hypertension |

Non-convulsive status should be cautiously observed in patients with prolonged altered consciousness, which may be mistaken commonly for postictal confusion. Signs include stereotypic movements like staring, head turning or eye blinking. Postictal confusion usually lasts for hours, but PRES and non-convulsive status can last for many days and can be mistaken for drug intoxication, psychosis or psychogenic states. If recognized and treated early, the clinical syndrome commonly resolves within a week.

CASE REPORT

A 35-year-old female was brought to the emergency room with the history of three episodes of generalized tonic–clonic seizures, urinary incontinence and altered sensorium since 3 hours. The patient was referred from a local hospital for further management. The patient had a headache prior to the onset of seizures. Patient relatives revealed that patient had the unsafe abortion 10 days ago and later developed severe fatigue, shortness of breath and pedal edema. Husband expired 3 years ago due to unknown chronic illness. Due to severe anemia (Hb: 3.4 gm/dl) and ongoing blood loss, the patient was transfused five units of blood in a local hospital. No history of hypertension was found as per medical records. No other significant history was available. On examination vital signs of the patient were normal. The patient was drowsy, not obeying commands, but withdraws limbs to painful stimuli, deep tendon reflexes were sluggish and a withdrawal response was seen in plantar reflex. There were no signs of meningeal irritation.

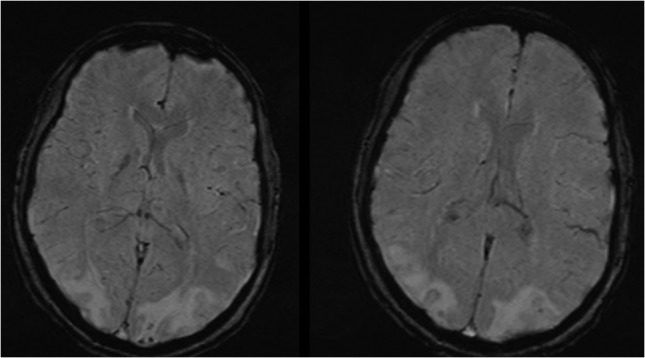

Laboratory examination revealed normal hemoglobin (13.8 g/dl), neutrophilic leukocytosis (18 000/dl), urinary tract infection (10–15 pus cells/high-power field) and elevated C-reactive protein (4.7 mg/dl). ESR, liver function tests and renal function tests were normal. Peripheral smear showed dimorphic anemia. Other blood tests, coagulation profile, autoantibodies and neoplastic markers were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed an increase in protein level (50 mg/dl). Chest radiography and arterial blood gas analysis were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging brain showed bilateral occipital, parietal, frontal cortex and subcortical white matter T2/Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensities (Figs 1–5), suggestive of PRES. Electroencephalography showed bilateral temporal–occipital epileptiform discharges at times becoming general. Electrocardiogram showed incomplete right bundle branch block.

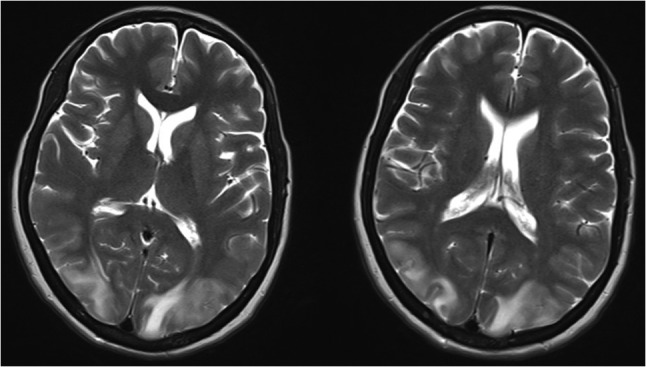

Figures 2:

Axial view showing bilateral occipital, parietal, frontal cortex and subcortical white matter T2/FLAIR hyperintensities.

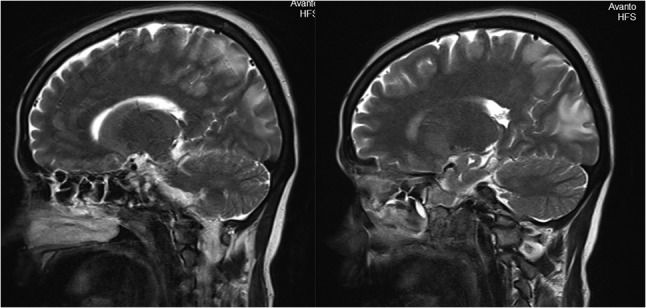

Figures 3:

Sagittal view of MRI brain showing bilateral occipital, parietal, frontal cortex and subcortical white matter hyperintensities.

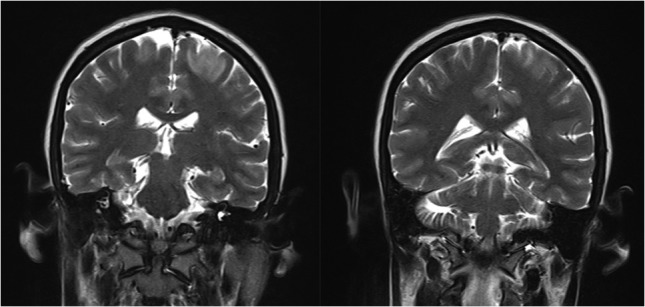

Figures 4:

Coronal view of MRI brain showing bilateral occipital, parietal, frontal cortex and subcortical white matter hyperintensities.

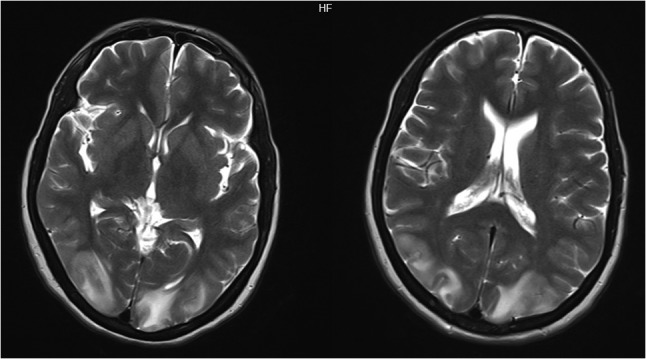

Figures 1:

Axial view of MRI brain showing bilateral occipital, parietal, frontal cortex and subcortical white matter hypherintensities.

Figures 5:

MRI brain showing bilateral occipital, parietal, frontal cortex and subcortical white matter hyperintensities.

The patient was admitted to intensive care unit and was managed with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, antiepileptics and monitoring of blood pressure. The patient improved symptomatically in form of normal sensorium, leukocyte counts and vital signs. The patient was discharged after 7 days of admission at request. Follow-up after 1 week was uneventful.

DISCUSSION

The term PRES has been used based on the similarity in the appearance on imaging, the common location of the parietal–occipital lobe or ‘posterior’ location of the lesions. The exact pathophysiological mechanism of PRES is still unclear. Three hypotheses have been proposed till now, which include (i) Cerebral vasoconstriction causing subsequent infarcts in the brain, (ii) Failure of cerebral autoregulation with vasogenic edema, and (iii) Endothelial damage with blood–brain barrier disruption further leading to fluid and protein transudation in the brain. The distinct imaging patterns in PRES are represented in Table 2 [5]. The reversible nature of PRES has been challenged recently based on new reports of permanent neurological impairment and mortality reaching 15%.

Table 2:

Imaging patterns in PRES

| Holohemispheric watershed |

| Superior frontal sulcus |

| Dominant parietal/occipital |

| Partial and/or asymmetric PRES |

No clinical studies are available till now regarding patients with PRES needing life-sustaining treatments. The improved knowledge and research about factors influencing the outcome of PRES will result in better early management, less morbidity and mortality. According to studies, delayed diagnosis and treatment may lead to mortality or irreversible neurological deficit. In hypertension associated or drug-induced PRES, the effective therapy includes withdrawal of offending agent, immediate control of blood pressure, anti-convulsive therapy and temporary renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis/peritoneal dialysis) if required. In Systemic lupus erythematosus-related PRES, aggressive treatment with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide is effective. Corticosteroids may improve vasogenic edema, but there is no solid evidence for usage in PRES.

Blood transfusion may cause a rapid increase in total blood volume, which further leads to cerebral blood flow overload. Abrupt or acute cerebral hyperperfusion exceeding the capacity of autoregulation of cerebral capillary perfusion pressure might result in vasogenic edema found in PRES. The possibility of severe anemia as the predisposing factor, due to the inadequate supply of oxygen to the brain may result in dysfunction of endothelial cells, further causing a functional loss or damage to the integrity of the blood–brain barrier in capillary circulation cannot be ruled out [6]. PRES associated with blood transfusion case reports are represented in Table 3. Our patient had no hypertension even transiently during the whole episode. In conclusion, PRES can be a major problem in rapid and massive blood transfusion. A high index of suspicion and prompt treatment can reduce morbidity, mortality and pave the path for early recovery.

Table 3:

PRES associated with blood transfusion case reports

| S.no. | Age/sex | Hb-pre and post transfusion (g/dl) |

Interval (days) | HTN | Sequelae | Cause of anemia | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45/F | 2.0/10.0 | 2 | Yes | None | Myoma uteri | [7] |

| 2 | 48/F | 3.0/8.0 | 6 | Yes | None | Myoma uteri | [8] |

| 3 | 47/F | 1.5/10.9 | 7 | No | Visual defect, numbness of extremity |

Aplastic anemia | [9] |

| 4 | 58/F | 7.7/10.9 | 8 | Yes | None | Cancer surgery | [10] |

| 5 | 77/F | 9.2/13.3 | 17 | Yes | None | Cancer surgery | [10] |

| 6 | 32/F | 5.7/12.5 | 5 | No | None | Myoma uteri | [11] |

| 7 | 42/F | 5.7/11.7 | 6 | No | None | CKD, Cirrhosis of liver | [12] |

| 8 | 56/F | 2.0/9.2 | 6 | Yes | None | Corpus uteri | [6] |

REFERENCES

- 1. McKinney AM, Short J, Truwit CL, McKinney ZJ, Kozak OS, SantaCruz KS, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: incidence of atypical regions of involvement and imaging findings. Am J Roentgenol 2007;189:904–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. New Engl J Med 1996. Feb 22;334:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwartz RB, Jones KM, Kalina P, Bajakian RL, Mantello MT, Garada B, et al. Hypertensive encephalopathy: findings on CT, MR imaging, and SPECT imaging in 14 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992;159:379–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartynski WS. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, part 1: fundamental imaging and clinical features. Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1036–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartynski WS, Boardman JF. Distinct imaging patterns and lesion distribution in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:1320–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wada KI, Kano M, Machida Y, Hattori N, Miwa H. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome induced after blood transfusion for severe anemia. Case Rep Clin Med 2013;2:332. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ito Y, Niwa H, Iida T, Nagamatsu M, Yasuda T, Yanagi T, et al. Post-transfusion reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome with cerebral vasoconstriction. Neurology 1997;49:1174–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boughammoura A, Touzé E, Oppenheim C, Trystram D, Mas JL. Reversible angiopathy and encephalopathy after blood transfusion. J Neurol 2003;250:116–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heo K, Park SA, Lee JY, Lee BI, Lee SK. Post-transfusion posterior leukoencephalopathy with cytotoxic and vasogenic edema precipitated by vasospasm. Cerebrovasc Dis 2003;15:230–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kawano H, Suga T, Terasaki T, Hashimoto Y, Baba K, Uchino M. Posterior encephalopathy syndrome in two patients after cancer surgery with transfusion. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2004;44:427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang YC, Tsai PL, Yeh JH, Chen WH. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome caused by blood transfusion: a case report. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2008;17:258–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sato Y, Hirose M, Inoue Y, Komukai D, Takayasu M, Kawashima E, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome after blood transfusion in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 2011;15:942–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]